Abstract

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this brief review is to highlight significant recent developments in survivorship research and care of older adults following cancer treatment. The aim is to provide insight into care and support needs of older adults during cancer survivorship as well as directions for future research.

Recent Findings

The numbers of older adult cancer survivors are increasing globally. Increased attention to the interaction between age-related and cancer-related concerns before, during, and after cancer treatment is needed to optimize outcomes and quality of life among older adult survivors. Issues of concern to older survivors, and ones associated with quality of life, include physical and cognitive functioning and emotional well-being. Maintaining activities of daily living, given limitations imposed by cancer treatment and other comorbidities, is of primary importance to older survivors. Evidence concerning the influence of income and rurality, experiences in care coordination and accessing services, and effectiveness of interventions remains scant for older adults during survivorship.

Summary

There is a clear need for further research relating to tailored intervention and health care provider knowledge and education. Emerging issues, such as the use of medical assistance in dying, must be considered in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

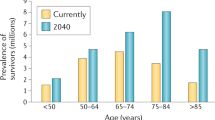

Older adults constitute one of the fastest-growing subgroups in the cancer population [1]. Over the next decade, the number of individuals 65 years and older who are diagnosed with cancer is expected to double, accounting for 67% of new cancer cases and reaching levels of 14 million worldwide [2]. Given advances in screening, treatment, and supportive care which have resulted in improved cancer outcomes, the population of older adult cancer survivors is also expected to escalate [3].

The aftermath of cancer treatment can have a significant impact on survivors [4, 5]. Physical, emotional, and practical changes during and after treatment may carry consequences that have a significant impact on the quality of life of survivors [6], carrying implications for recovery and maintenance of autonomy and independence. Early evidence illustrates that immediate recovery following cancer treatment and improvements in survival for older adults following cancer is slower than for younger survivors [7••]. For older adults, who may be already dealing with other comorbid conditions and effects of aging, the added burden of late and long-term effects may be particularly troublesome [8].

Challenges emerging during survivorship add to the complexity of meeting the needs of older adults after cancer [9, 10••]. Evidence is beginning to accumulate regarding the unique, multi-dimensional needs of older adults following cancer [11•], and, with it, an understanding of challenges they may face as cancer survivors [12]. However, further work is needed to fully understand survivorship experiences for this population, gaps in care delivery, and how those gaps could be mitigated.

This paper highlights significant recent developments in survivorship research and care for older adults following cancer. We define survivorship as the interval from completion of primary cancer treatment until the identification of recurrent or progressive disease [13]. Our aim is to provide insight into care and support needs of older adults during cancer survivorship as well as directions for future research.

Methods

A brief review of literature from the last 3 years reporting on older adult cancer survivors aged 65 years and older was undertaken. Relevant topics were identified through consultation with experts in the field and used for search purposes. Keywords used together with “older adults” and “cancer survivors” were accelerated aging, polypharmacy, late/long-term effects, cognitive changes, neuropathy, comprehensive geriatric assessment, survivorship care plans, depression, ethics, and MAiD. A search of Medline via PubMed using the keywords identified relevant English publications from the past 3 years. All article types were considered (e.g., reviews, perspectives papers, descriptive/intervention studies). Each article was reviewed, significant findings identified, and results grouped into broad topic areas. These broad topics are summarized below, presenting significant developments regarding research and care of older cancer survivors reported over the past 3 years.

Aging and Cancer Survival

Four articles addressed patterns of survival among older adults and the impact of little research that considers age-related concerns on patterns and quality of survival in this group. There have been consistent improvements in cancer survival over the past two decades; however, these improvements are smaller for those aged 75 years and older at diagnosis and there is greater variation in 5-year survival across countries for this age group [7••]. Cellular and molecular changes that occur in non-cancerous cells with aging contribute to a microenvironment that promotes tumor progression and to treatment responses that may impact outcomes, including survival, but are seldom considered in pre-clinical trials [14•]. In addition, a lack of inclusion of older adults in clinical trials, and consideration of outcomes of importance to older adults, means that treatment decisions for older adults with cancer are often based on evidence acquired from younger adults with fewer comorbidities, less polypharmacy, and different physiology [15].

Accelerated Aging

Not only does aging impact the experience of cancer, but the disease and treatment can also impact the experience of aging among cancer survivors. There is increasing work documenting patterns of accelerated or accentuated aging among people who have experienced cancer treatment [16, 17••, 18]. Aging is often understood as the “time-dependent accumulation of cellular damage” [14•]. Accelerated or accentuated aging occurs when cancer and cancer treatments contribute to genotoxic and cytotoxic damage that contributes to anatomic and functional changes that mirror those expected with aging, but at a younger age or to a greater degree than would occur in the absence of cancer [17••]. We identified seven articles exploring relationships among physiological markers of aging, behavioral or functional changes associated with aging, and the receipt of cancer treatment. The aging phenotype caused by cancer and its treatment has been characterized by adverse physical and cognitive consequences, including fatiguability and poor endurance [19], persistent cognitive impairment [20], onset of chronic health conditions [16, 21••, 22], and decreased survival [17••, 22]. Researchers are exploring physiological mechanisms that may contribute to this accelerated aging phenotype among cancer survivors, including DNA damage [17••, 22], stem cell depletion [17••], alterations in cerebral blood flow [20], shortening of telomere length [16], cellular senescence [17••, 21••], and disruption of pathways that mitigate the damaging effects of inflammation and oxidative stress [20, 21••]. These physiological changes may be reflected in clinical measures of functional status, frailty, and cognitive function, including subjective measures, such as self-report measures of activities of daily living, and objective measures, such as gait speed and grip strength [17••]. These changes may also be reflected in biological measures. The authors of recent reviews present a thorough discussion of the biomarkers associated with aging that may be used to assess and/or predict accelerated aging [17••] or resilience [21••].

To increase understanding of cancer treatment on aging, appropriate clinical and biological measures of aging of must be incorporated into clinical trials [17••]. Resilience, defined as capacity to resist or regain physical, cognitive, or psychological function and well-being after a stressor, diminishes with aging and may be defined by age-related biologic processes [21••]. If so, then clinical and biological measures of aging may also predict resilience in older survivors, and identifying associated physiological and molecular mechanisms may promote the identification of protective factors and strategies to promote resilience and well-being in survivorship [21••]. Some strategies to prevent accelerated aging include treatment with pharmaceuticals or nutraceuticals that reduce inflammation, treat cardiovascular risk, or improve cardiac function, as well as behavioral strategies including exercise-based interventions considering the unique needs of survivors [16].

Issues of Particular Concern Among Older Adult Survivors

Eighteen articles describing physical issues, comorbidities, and polypharmacy for older cancer survivors were identified. Ten were studies of older cancer survivors, five focused on older breast cancer survivors, and others addressed issues with older survivors of hematological, oral-digestive and prostate cancers, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Physical Issues

Studies about older adults following cancer treatment have chiefly focused on physical health and function [10••, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29, 30••, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The impaired physical function has been studied as a result of treatment [25,26,27,28] and several studies compared symptom burden with non-cancer controls or younger cancer survivors [23, 26, 28, 29, 30••, 31,32,33, 35]. In a Canadian survey of over 3000 cancer survivors 75 years or older, 80% reported physical concerns [11•]. Specifically impaired physical function, decline in cardiovascular and other health conditions, fatigue, and depression were studied. The effect of cancer treatment on cardiovascular systems, physical balance, mobility, and neuropathy were reported as significant in older cancer survivors [10••, 25, 28].

While the importance of physical function in older cancer survivors was explored in some studies, cognitive impairment was highlighted in more than half. Cognitive decline was observed as common in older cancer survivors, but findings varied, ranging from 12 to 75% [33]. One study observed no association between chemotherapy and cognitive function [27]. In others, older cancer survivors were shown to demonstrate the decline in executive functioning and verbal memory more frequently than younger adults following treatment [26, 33]. Regier et al. [33] found up to 40% of older cancer survivors exhibited cancer-related cognitive impairment (sustained attention, memory, and verbal fluency) 18 months post-diagnosis while survivors who exhibited high psychoneurological symptoms at diagnosis were more likely to experience greater cognitive decline post-treatment [25, 30••, 35].

Comorbidities and Polypharmacy

It is estimated 25% of older adults with cancer have five or more comorbid conditions [10••]. In a recent Canadian study, over 70% of adult survivors 75 years and older reported comorbidities, the four most common being cardiovascular/heart disease (45%); arthritis, osteoarthritis, or other rheumatic diseases (40%); diabetes (16%); and mental health (7%) [11•]. Given the prevalence of other diseases and medical conditions, it is interesting that less than half of the articles addressed comorbidities and fewer discussed the importance of polypharmacy and its implications. While older adults comprise less than 15% of the population of the USA, for example, they account for over 30% of both non-prescription and prescription medications [30••]. Magnusson et al. [30••] state that polypharmacy is defined as the use of five or more medications but recognize that researchers less often address appropriate versus inappropriate polypharmacy (lacking evidence base, adverse reactions, etc.). On average, older adults with cancer take nearly 10 different medications and many are uncertain about the reasons they need these medications [10••]. The impacts of adverse drug effects (e.g., falls, cognitive issues) and drug and disease interactions can be severe. In addition, Guerard et al. [10••] note that a fragmented group of providers is often responsible for the provision of healthcare to older adults which can result in a lack of communication and coordination among the various specialists involved [30••] and uncertainty on the part of survivors about where they should seek assistance for an issue [12].

Overall cancer and its treatments are associated with higher levels of symptom burden and greater loss of well-being over time in older adult survivors, as compared to older adults without cancer, suggesting the need for greater surveillance and opportunities for intervention [31]. In addition, many older adults are at risk for experiencing physical, emotional, and practical concerns following cancer treatment yet are not obtaining desired help [12]. Coughlin et al. noted that given prevalent age-related issues such as comorbidities, osteoporosis, symptoms, physical functioning, cognitive functioning, nutrition, and physical activity [37], appropriate surveillance, screening (including pre-screening for at-risk individuals), and interventions both during and post-treatment are critical to improve associated functional/neurological changes and improve the overall quality of life [24, 30••, 31,32,33]. Future research is needed about the nature and extent of disability and symptom burden to develop survivorship programs for this distinct patient population [29] and inform the development of guidelines and policies in conjunction with patients’ preferences and goals [10••].

Factors Influencing Quality of Life in Older Adult Survivors

A primary direction of research regarding older adult cancer survivors has been identifying factors that influence quality of life. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is seen as a primary outcome given that priorities and values for older adults shift as they age [38] and acknowledge they have few remaining years. However, age alone is insufficient to explain variations in this populations’ HRQOL. Both cancer (e.g., cancer type, treatment modality, recurrence) and non-cancer-related (e.g., education, income, residence) factors contribute [38,39,40].

Most studies reviewed included survivors of breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancers, making use of existing databases and frequently resulting in sizeable sample sizes (121 [41] to 271,640 [42•]. Studies involved various time intervals following completion of treatment (1 to > 10 years), definitions of older adults (e.g., 60+, 75+, 70+, 75+, and 80+ years) and combinations of physical, psychological, emotional, social, and demographic variables. Overall, there is agreement that HRQOL is lower in older adult survivors than in general older adult populations [42•, 43].

Consistently physical variables have the strongest associations with HRQOL. Although these variables were measured in various ways, (e.g., physical well-being [44•], functional health limitations [38] disability [45], mobility [46, 47], and physical health status [48], the capacity to manage activities of daily living and maintain independence were critical for older adult survivors and contributed to HRQOL. Cancer type [49•], the number of comorbidities [42•, 45], length of time dealing with side effects, side effect severity [43, 50, 51], duration of chronic illness [39], and deteriorating health status [41, 45] are key variables with negative influence on HRQOL. Experiencing fatigue [44•], frailty [53••], difficulty performing Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) [53••], difficulty walking [46],) and increased risk for falls [47, 48] are challenges associated with poor HRQOL outcomes [53••] in older survivors. In a sample of 3274 older cancer survivors, when asked to identify the main challenge, they experienced in transitioning to survivorship, over 68% identified physical limitations [11•].

Psychosocial variables have not been explored as frequently as physical variables in older cancer survivors. Depression [40, 50], body image (appearance) [51, 54], reduced optimism [55], altered sexual intimacy [56], treatment decision regret [57], chronic stress (55), lack of emotional support [39], and post-traumatic growth [41] are associated with reduced HRQOL. Depression is concerning in this population, reaching levels of 30% in community-dwelling older survivors [40]. Increased levels of depression are associated with female gender, number of symptoms [50], living alone [40], reduced income [40], and recurrence [40]. Additionally, social well-being, which is associated with social support and satisfaction with psychosocial need fulfillment [58], is associated with QOL [41]. Attending to environmental barriers which hinder engagement in social activities and reintegration in the community is important for older survivors given isolation contributes to reduced QOL [58].

Two variables beginning to receive attention in survivor populations are income and rurality. A larger proportion of older cancer survivors with low household income have concerns and seek help for physical, emotional, and practical issues than those with higher incomes [59]. However, similar proportions of low- and high-income older survivors experienced difficulty obtaining help for their concerns. In general, lower levels of subjective socioeconomic status are associated with lower QOL across all domains [39, 41, 49•], non-adherence in purchasing medicines and supplies [60], and foregoing tests, procedures, and care [61].

Although rurality has been investigated regarding access to screening, diagnostic, and treatment services, few studies have looked at access to services for survivorship care, especially for older adults. Access to services presents different challenges for survivors than for cancer patients; survivors want services close to home rather than traveling for specialist treatment [62]. Moss et al. [42•] reported QOL is higher for older survivors living in urban settings where access to ancillary services such as social work, physiotherapy, and support groups is easier. The need to leverage the higher social integration in rural communities to enhance emotional support for older adult survivors is recommended.

Interventions for Older Adult Cancer Survivors

Few studies regarding the effectiveness of interventions designed for older adult cancer survivors were identified in our search. Interventions receiving the most attention included incorporating comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and physical exercise.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Older adults present a wide variation in health and functional status that may be exacerbated by cancer treatment and present various life challenges [63]. The use of screening and other assessment tools is helpful for identifying patient needs and planning appropriate interventions, particularly for distinct populations such as older adults.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is a process of evaluating and improving functional ability, physical health, cognition and mental health, and socio-environmental circumstances of older adults. Assessment results are reviewed by healthcare teams, discussed with patients, and incorporated into care plans. Nishuima et al. [64•], for example, propose an approach to CGA comprised of assessments in 10 impairment domains (cognition, mood, communication, mobility, balance, bowels, bladder, nutrition, daily activities, and social) and a single comorbidity domain. Geriatric assessed impairments were associated with increased hospitalizations and long-term care use in older adults with cancer [65]. Benefits of CGA include treatment effectiveness and efficacy, prediction of mortality and cancer treatment tolerance, and decision-making to establish the appropriate treatment of cancer [66••]. CGA also helps identify significant comorbidities and polypharmacy [67] and patients who might benefit from less invasive and more tolerable evidence-based treatments [68]. Studies have shown that participants receiving CGA-based intervention report significantly better HRQOL [63].

While GA is helpful in identifying deficits in older adults with cancer and is considered a critical component in oncology treatment planning, with demonstrated feasibility and effectiveness, it is not widely implemented [63, 65, 67, 68]. The incorporation of geriatric screening can be taxing to this population particularly if multiple surveys/screening tools related to geriatric domains are used in addition to those related to distress and patient-reported outcomes. In addition, healthcare providers find the incorporation of CGA into daily practice time-consuming [63]. Successful implementation requires the involvement of the multi-disciplinary team, strong administrative and patient scheduling support, and planning [66••]. Given the complexities of care for older adults with cancer, the introduction of CGA in post-treatment care, as an aspect of survivorship care planning, for example, could assist in isolating survivors’ critical health issues, identifying appropriate therapies, and enhancing survivorship care coordination.

Physical Activity/Exercise

More than 50% of older cancer survivors are not achieving standards for physical activity (PA) [44•, 54]. Given the potential impact of PA on recovery and capacity to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), finding relevant and effective physical programming for older adults with cancer has become a priority. Unfortunately, current guidelines are based on research with younger populations. A recent systematic review of the effectiveness of PA interventions in older survivors identified 14 studies [69••]. However, interventions varied in duration (1 to 12 months), intensity, settings, and outcome measurements, making it difficult to draw conclusions about specific approaches for older survivors.

Given the choice about what interventions to pursue in one study, older adults selected PA [70]. Older survivors reported they used PA programs to increase engagement and performance of ADLs and reduce sleep disturbances and fatigue [70,71,72]. In addition, interventions help with issues of body image and psychosocial distress [44•, 54, 72]. Barriers included time, transportation, lack of facilities, weather, and pain [44•, 70, 72] while their preferences included structured programs incorporated with cancer care, having supervision, and being able to use equipment aids [70, 72].

Older Adult Survivor Perspectives Regarding Experiences with Care

A small but growing body of evidence is emerging which captures survivors’ perspectives about experiences with cancer care delivery and suggestions for improvement. Given the complexity of needs and challenges in addressing concerns, it is important to understand the views of older survivors who have accessed services.

In quantitative investigations, higher access to services and higher self-reported health status were associated with better care experiences [73]. Variations in care experiences exist by education, gender, and cancer types. Scores indicating patient perceptions of higher care coordination are associated with living rurally at diagnosis, having fewer specialists involved in care, and more frequent visits with a family doctor [74]. Low scores are reported by women with metastatic disease, those with higher education, and individuals over 80 years of age [74].

A thematic analysis from Canada described perspectives of older adults regarding challenges experienced during survivorship care and suggestions for improvements. Themes regarding challenges included: “Getting back on my feet,” “Adjusting to life changes,” and “Finding the support I need” [11•], while those regarding suggestions for improvements were, “Offer me support,” “Make access easy for me,” and “Show me you care” [36]. In this same study, communication, information, and access to a range of services were considered important yet remained gaps in service delivery by 82% of respondents.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, older adult survivors were reported to be among one of the most disadvantaged groups and needed special consideration in terms of support [75]. One qualitative study reported older survivors [76] indicated they understood the situation but that they missed interactions with others. Survivors found virtual clinic appointments were helpful, especially in reducing needs for transportation, but they were not as beneficial for social interaction as in-person visits.

Suggestions Regarding Future Research and Care Across Articles

Many articles contained recommendations about screening to identify at-risk individuals and utilizing deeper assessment of needs to build tailored interventions. Incorporating self-report by older survivors for aspects such as physical health, mobility, and emotional distress was emphasized [43, 48, 50] together with a relevant discussion of preferences [38]. Older survivors are a heterogeneous population with unique and complex needs. The priorities in unmet needs vary [12] and what will be most effective in meeting those needs differs from other age groups [77]. Yet health care professionals report a lack of confidence in caring for this population [78]. Enhancing knowledge and skill for survivorship care of older adults, guided by standards for optimizing care for this population [78, 79], needs consideration.

Several areas of interventions used with other populations may have potential relevance for the older adult survivor cohort and could be considered for future program design and implementation. Lay Navigation [80], nurse coordination models [74], home telehealth [74, 76], use of survivorship care plans [81, 82], and active involvement of caregivers/partners in care planning [83, 84] could be explored given the interventions were designed with the unique needs of older survivors in mind.

An Emerging Consideration from Clinical Care

An emerging issue regarding the clinical care of older adults with cancer is the marked increase in requests for medical assistance in dying (MAiD) [85]. The concept of MAiD encompasses the terms assisted suicide and euthanasia [86•] with MAiD legislation originally aimed to ease the burden of suffering of imminent death. Conversation of the right to access MAiD most often centers on individual autonomy and dying with dignity (e.g., Selby et al. [87•]), conceptualized as having control over one’s destiny. It has been strongly associated with an unacceptable situation of being dependent and a burden to the family. Definitions and restrictions of MAiD, guided by healthcare providers’ standards of practice, organizational policies, and professional codes of ethics, vary depending on jurisdiction-specific legislation. MAiD is often framed as a procedure; however, this patient choice also represents an extensive social movement in which a multitude of legal, ethical, regulatory, and clinical factors converge with highly personal values and beliefs involved. No discussion about this issue emerged in the literature regarding older adult cancer survivors, leaving little guidance for negotiating the difficulty of providing ethical options while also countering ageist discourses influencing patient choices.

The majority of people who consider MAiD have a pre-existing cancer diagnosis [88•, 89, 90, 91•]. A recent Canadian survey of oncologists reported 70% encountered a patient request for MAiD [92••]. Nurses also grapple with requests for medical assistance in dying (MAiD) among older adults with cancer, perceiving it to be a response to suffering, being a burden in survivorship, and not wanting to engage in treatment or transition to palliative care [80]. Concerns that uncontrolled physical and psychological symptoms may prompt premature requests for MAiD are warranted [91•]. Furthermore, understanding the interplay of depression and demoralization, factors which are often undertreated and unaddressed in older adults, with MAiD requests is essential. The research provides a better understanding of these influences and provides guidance for practice underway [93•].

In support of appropriate access and choice regarding MAiD, current evidence supports that clear and direct discussions with an interdisciplinary approach enhance therapeutic relationships [91•, 94, 95]. At the same time, MAiD must remain person-centered to humanize a medicalized activity [96••]. Such conversations have implications for all patients, and more specifically older adults with cancer. The conversations are apt to occur within a largely unquestioned backdrop of system-level ageism, an often unaccounted for force impacting cancer care [36]. Healthcare professionals must consider messages they transmit when they commit to having explicit conversations about assistance for dying but not to the assistance required for living with the challenging side effects of cancer and subsequent treatment as patients move in and through survivorship. Evidence-informed guidelines are essential to support the transition through active treatment to survivorship. Clearly, there is need for further research in this area in the context of survivorship.

Existing Guidelines to Inform Intervention

Guidelines established by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] [97] and the American Society of Clinical Oncology [98] provide a framework for assessing and managing age-related concerns prior to and during cancer treatment. In addition, priorities to optimize care of older adults with cancer have been identified [79, 99, 100] and recommendations to support quality of life during all phases of the cancer trajectory, including survivorship, have been developed [101].

Conclusion

The body of evidence for guiding care of older adult cancer survivors is growing and confirms the unique and complex needs of this population. Screening at-risk individuals and connecting them to appropriate resources is important. Tailored assessments and interventions before, during, and after treatment are necessary to optimize survivorship care. However, additional research is required to design truly age appropriate and effective care approaches. By strengthening the evidence base to better inform treatment decision-making, outcomes for older adults with cancer may be improved, both in terms of survival and quality of life in survivorship.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:363–85.

Pilleron S, Sarfati D, Janssen-Heijnen M, et al. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:49–58.

Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1996–2005.

Lerro CC, Stein KD, Smith T, Virgo KS. A systematic review of large-scale surveys of cancer survivors conducted in North America, 2000–2011. J Cancer Survivorship. 2012;6:115–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0214-1.

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2006

Hamrood R, Hamrood H, Merhasin I, Kenan-Boker L. Chronic pain and other symptoms among breast cancer survivors: prevalence predictors and effects on quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;167(1):157–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4485-0 (Epub 2017 Aug 31).

Arnold M, Rutherford MJ, Bardot A, Ferlay J, Andersson TML, Myklebust TÅ… Bray F. Progress in cancer survival, mortality, and incidence in seven high-income countries 1995-2014 (ICBP SURVMARK-2): A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(11);1493–1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30456-5. Longitudinal, population-based study in which researchers analyzed patient-level data of 3.9 million patients drawn from population-based cancer registries in seven countries. They calculated age-standardized net survival at 1 and 5 years by tumor site, age group, and period of diagnosis.

Corbett T, Bridges J. Multimorbidity in older adults living with and beyond cancer. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2019;13:220–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000439.

Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM. Cancer Survivorship Issues Life after treatment and implications for an aging population. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:2662–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.55.836.

Guerard EJ, Nightingale G, Bellizzi K, Burhenn P, Rosko A, Artz AS, et al. Survivorship care for older adults with cancer: U13 Conference Report. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;(4):305-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2016.06.005. This article presents a summary of the Cancer and Aging Research Group (National Institute on Aging and National Cancer Institute) 2015 conference that discussed survivorship care for older adults. Emerging themes included that survivorship must evolve to meet the needs of older adults; older adult survivors require tailored survivorship care and plans; the suitability of the interdisciplinary team to provide older adult survivorship care; and patient advocacy is needed throughout the care continuum.

Fitch MI, Nicoll I, Lockwood G, Strohschein FJ, Newton L. Main challenges in survivorship transitions: perspectives of older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(4):632–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.09.024. A secondary analysis of early cancer survivorship for older adults revealing gaps in care and raises concerns about unexamined ageism within the Canadian cancer care system, with the concurrent need for comprehensive geriatric assessments along with multi-modal proactive treatment plans.

Fitch MI, Nicoll I, Lockwood G, Strohschein FJ, Newton L. Cancer survivors 75 years and older: physical, emotional and practical needs. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021; Apr 21. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002855.

Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5112–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284.

Fane M, Weeraratna AT. How the ageing microenvironment influences tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(2):89–106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-019-0222-9. A review in which the authors discuss how the ageing microenvironment contributes to tumor progression and responses to cancer therapy, including survival.

Outlaw D, Williams GR. Is the lack of evidence in older adults with cancer compromising safety? Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19(9):1059–61.

Armenian SH, Gibson CJ, Rockne RC, Ness KK. Premature aging in young cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019; 111(3):226–232.

Guida JL, Ahles TA, Belsky D, Campisi J, Cohen HJ, Degregori J… Hurria, A. Measuring aging and identifying aging phenotypes in cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111(12):1245–1254. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djz136. Provides a summary of the National Cancer Institute’s 2018 interdisciplinary think tank concerning aging-related consequence of cancer and cancer treatment, which addressed conceptual, measurement, and methodological challenges in this field.

Sedrak MS, Hurria A. Cancer in the older adult: implications for therapy and future research. Cancer. 2018;124(6):1108–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31236.

Gresham G, Dy SM, Zipunnikov V, Browner IS, Studenski SA, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Schrack JA. Fatigability and endurance performance in cancer survivors: analyses from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Cancer. 2018;124(6):1279–87.

Carlson BW, Craft MA, Carlson JR, Razaq W, Deardeuff KK, Benbrook DM. Accelerated vascular aging and persistent cognitive impairment in older female breast cancer survivors. Geroscience. 2018;40(3):325–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-018-0025-z.

Sedrak MS, Gilmore NJ, Carroll JE, Muss HB, Cohen HJ, Dale W. Measuring biologic resilience in older cancer survivors. J ClinOncol. 2021;39(19):2079–2089. In this review, authors highlight the emerging concept of resilience in older cancer survivors, considering potential biomarkers and interventions that may promote resilience in this population.

Slavin TP, Sun CL, Chavarri-Guerra Y, Sedrak MS, Katheria V, Castillo D, et al. Older breast cancer survivors may harbor hereditary cancer predisposition pathogenic variants and are at risk for clonal hematopoiesis. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(2):316–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.09.004.

Bevilacqua L, Dulak D, Schofield E, Starr TD, Nelson CJ, Roth AJ. Prevalence and predictors of depression, pain, and fatigue in older- versus younger-adult cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2018;27(3):900–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4605.

Blackwood J, Rybicki K, Huang M. Cognitive measures in older cancer survivors: An examination of validity, reliability, and minimal detectable change. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;1:146–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.06.015.

Carlson BW, Craft MA, Carlson JR, Razaq W, Deardeuff KK, Benbrook DM. Accelerated vascular aging and persistent cognitive impairment in older female breast cancer survivors. Geroscience. 2018;40(3):325–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-018-0025-z.

La Carpia D, Liperoti R, Guglielmo M, Di Capua B, Devizzi LF, Matteucci P, et al. Cognitive decline in older long-term survivors from Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(5):790–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.01.007.

Morin RT, Midlarsky E. Treatment with chemotherapy and cognitive functioning in older adult cancer survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(2):257–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.016.

Fino PC, Horak FB, El-Gohary M, Guidarelli C, Medysky ME, Nagle SJ, Winters-Stone KM. Postural sway, falls, and self-reported neuropathy in aging female cancer survivors. Gait Posture. 2019;69:136–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2019.01.025.

Götze H, Köhler N, Taubenheim S, Lordick F, Mehnert A. Polypharmacy, limited activity, fatigue and insomnia are the most frequent symptoms and impairments in older hematological cancer survivors (70+): Findings from a register-based study on physical and mental health. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(1):55–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2018.05.011.

Magnuson A, Sattar S, Nightingale G, Saracino R, Skonecki E, Trevino KM. A practical guide to geriatric syndromes in older adults with cancer: a focus on falls, cognition, polypharmacy, and depression. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019n;39:e96–e109. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_237641. Identifies potential screening tools to identify geriatric syndromes and highlights the significance of falls, cognitive impairment, polypharmacy, and depression in older adults with cancer.

Mandelblatt JS, Zhai W, Ahn J, Small BJ, Ahles TA, Carroll JE, et al. Symptom burden among older breast cancer survivors: the Thinking and Living with Cancer (TLC) study. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1183–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32663.

Meneses K, Benz R, Bail JR, Vo JB, Triebel K, Fazeli P, et al. Speed of processing training in middle-aged and older breast cancer survivors (SOAR): results of a randomized controlled pilot. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;168(1):259–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4564-2.

Regier NG, Naik AD, Mulligan EA, Nasreddine ZS, Driver JA, Sada YH, Moye J. Cancer-related cognitive impairment and associated factors in a sample of older male oral-digestive cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2019;28(7):1551–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5131.

Shah R, Chou LN, Kuo YF, Raji MA. Long-term opioid therapy in older cancer survivors: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(5):945–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15945.

Tometich DB, Small BJ, Carroll JE, Zhai W, Luta G, Zhou X, et al. Thinking and Living with Cancer (TLC) Study. Pretreatment psychoneurological symptoms and their association with longitudinal cognitive function and quality of life in older breast cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(3):596–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.11.015.

Fitch MI, Nicoll I, Lockwood G, Newton L, Strohschein FJ. Improving survivorship care: perspectives of cancer survivors 75 years and older. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(3):453–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.09.012.

Coughlin SS, Paxton RJ, Moore N, Stewart JL, Anglin J. Survivorship issues in older breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;174(1):47–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-05078-8.

Lapinsky E, Man LC, MacKenzie AR. Health-related quality of life in older adults with colorectal cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(9):81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-019-0830-2 (PMID: 31359163).

Doran P, Burden S, Shryane N. Older people living well beyond cancer: the relationship between emotional support and quality of life. J Aging Health. 2019;31(10):1850–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264318799252.

Doege D, Thong MSY, Koch-Gallenkamp L, Jansen L, Bertram H, Eberle A, et al. Age-specific prevalence and determinants of depression in long-term breast cancer survivors compared to female population controls. Cancer Med. 2020;9(22):8713–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3476.

Yang S-K, Ha Y. Exploring the relationships between posttraumatic growth, wisdom, and quality of life in older cancer survivors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(9):2667–72. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.9.2667.

Moss JL, Pinto CN, Mama SK, Rincon M, Kent EE, Yu M, Cronin KA. Rural–urban differences in health-related quality of life: patterns for cancer survivors compared to other older adults. Qual Life Res. 2021;30:1131–1143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02683-3. This study has a very large sample size and one of the first to explore rural-urban differences among older cancer survivors.

Winters-Stone KM, Medysky ME, Savin MA. Patient-reported and objectively measured physical function in older breast cancer survivors and cancer-free controls. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(2):311–6.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2018.10.006.

Shuk D, Cheung T, Takemura N, Chau PH, Yee A, Ng M, Xu X, Lin CC. Exercise levels and preferences on exercise counselling and programming among older cancer survivors: a mixed-methods study. JGO. 2021;12(8):1173–1180.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2021.05.00. Study provides interesting insight into the preferences of older adult survivors regarding how exercise programs could be designed with their needs in mind.

Diemling GT, Pappada H, Ye M, Nalepa E, Ciaralli S, Phelps E, Burant CJ. Factors affecting perceptions of disability and self-rated health among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. J Aging Health. 2019;31(4):667–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317745745.

Brown JC, Narhay MO, Harhay MN. Self-reported major mobility, disability and mortality among cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018; 9(5):459–463. 1016/j.jgo.2018.03.004

Huang MH, Blackwood J, Godoshian M, Pfalzer L. Predictors of falls in older survivors of breast and prostate cancer: a retrospective cohort study of surveillance, epidemiology and end results-Medicare health outcomes survey linkage. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(1):89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2018.04.009.

Sulicka J, Pac A, Puzianowska-Kuźnicka3 M, Zdrojewski T, Chudek J, Tobiasz-Adamczyk B, et al., Health status of older cancer survivors—results of the PolSenior study. J Cancer Survivorship. 2018;12:326–333 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0672-6

Ramsey SD, Hall IJ, Smith JL, Ekwueme DU, Fedorenko CR, Kreizenbeck K, et al. A comparison of general, genitourinary, bowel, and sexual quality of life among long term survivors of prostate, bladder, colorectal, and lung cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(2):305–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.07.014. This study offers insight into an often-overlooked aspect of quality of life in older adults (sexual activity). It includes a sample of various cancer types.

Levkovich I, Cohen, Alon S, Evron E, Pollack S, Fried, et al. Symptom cluster of emotional distress, fatigue and cognitive difficulties among young and older breast cancer survivors: the mediating role f subjective stress. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9(5):469–475. 1016/j.jgo.2018.05.002

Davis C, Tami P, Ramsay D, Melanson L, MacLean L, Nersesian S, Ramjeesingh R. Body image in older breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncology. 2020;29:823–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5359.

Koll TT, Semin JN, Brodsky R, Fisher AL, High R, Beadle JN. Health-related and sociodemographic factors associated with physical frailty among older cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(1):96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jco.2020.04.015.

Blackwood J, Karczewski H, Huang MH, Pfalzer L. Katz activities of daily living disability in older cancer survivors by age, stage, and cancer type. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(6):769–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00891-x. This article describes the range of potential impairments in activities of daily living cancer survivors could experience. It is a strong case for screening for ADL impairments as a regular aspect of care for older survivors.

Zhang X, Pennell ML, Bernardo BM, Crane T, Shadyab AH, Paskett ED, et al. Body image, physical activity and psychological health in older female cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(7):1059–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo2021.04.007.

Chow PI, Shaffer LM, Lohman MC, LeBaron VT, Fortuna KL, Ritterband LM. Examining the relationship between changes in personality and depression in older adult cancer survivors. Aging Ment Health. 2019;24(8):1237–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1594158.

Arthur EK, Wordy B, Carpenter KM, Krok-Schoen JL, Quick AM, Jenkins LC, et al. Let’s get it on: addressing sex and intimacy in older cancer survivors. JGO. 2021;12(2):312–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.08.033.

Karauturi MS, Lei X, Shen Y, Giordano SH, Swanick CW, Smith BD. Long-term decision regret surrounding systemic therapy in older breast cancer survivors: a population-based survey study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(6):973–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.03.013.

Loew K, Lynch MF, Lee J. Social support, basic psychological needs, and social well-being among older cancer survivors. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2021;92:100–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415019887688.

Fitch MI, Nicoll I, Lockwood G, Loiselle CG, Longo CJ, Newton L, Strohschein FJ. Exploring the relationships between income and emotional/practical concerns and help-seeking by older adult cancer survivors: a secondary analysis. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2021.11.007.

Gu D, Shen C. Cost-related medication nonadherence and cost-reduction strategies among elderly cancer survivors with self-reported symptoms of depression. Popul Health Manag. 2020;23(2):132–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2019.0035.

Longo CJ, Fitch MI. Unequal distribution of financial toxicity among people with cancer and its impact on access to care: a rapid review. Current Opinion (ePub 2021) https://doi.org/10.1097/spc.0000000000000561

Fitch MI, Lockwood G, Nicoll I. Physical, emotional, and practical concerns, help-seeking and unmet needs of rural and urban dwelling adult cancer survivors. J Eur Oncol Nurs. 2021;53:101976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101976.

Fitch MI, Strohschein FJ, Nyrop K. Measuring quality of life in older people with cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2021;15(1):39–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000535.

Nishijima TF, Shimokawa M, Esaki T, Morita M, Toh Y, Muss HB. A 10-item frailty index based on a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (FI-CGA-10) in Older Adults with Cancer: Development and construct validation. Oncologist. 2021;26(10):e1751–e1760. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13894. Study of the creation and testing of a user-friendly frailty index based on comprehensive geriatric assessment with over 500 older adults with various cancer types. Results were determined more quickly and interpreted in a more clinically sensible manner than existing tools.

Williams GR, Dunham L, Chang Y, Deal AM, Pergolotti M, Lund JL, et al. Geriatric assessment predicts hospitalization frequency and long-term care use in older adult cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(5):e399–409. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.18.00368.

Overcash J, Ford N, Kress E, Ubbing C, Williams N. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment as a versatile tool to enhance the care of the older person diagnosed with cancer. Geriatrics (Basel). 2019;24;4(2):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4020039. Examination of how a comprehensive geriatric assessment can be tailored to ambulatory geriatric oncology programs in academic cancer centers and to community oncology practices with varying levels of resources.

Williams GR, Kenzik KM, Parman M, Al-Obaidi M, Francisco L, Rocque GB, et al. Integrating geriatric assessment into routine gastrointestinal (GI) consultation: the Cancer and Aging Resilience Evaluation (CARE). J Geriatr Oncol. 2020;11(2):270–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.04.008.

Cope DG, Reb A, Schwartz R, Simon J. Older adults with lung cancer: assessment, treatment options, survivorship issues, and palliative care strategies. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(6):26–35. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.CJON.S2.26-35.

Forbes C, Swan F, Greenley SL, Lind M, Johnson MJ. Physical activity and nutrition interventions for older adults with cancer: A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2020;14:689–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00883-x / Published online: 24 April 2020. A recent literature review of effectiveness of physical activity interventions for older adult cancer survivors describes various interventions and can inform future designs.

Lyons KD, Newman R, Adachi-Mejia AM, Whipple J, Hegel MT. Content analysis of a participant-directed intervention to optimize activity engagement of older adult cancer survivors. OTJR: Occup Participation Health. 2018;38(1):38–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449217730356

Paulo TRS, Rossi FE, Viezel J, Tosello GT, Seidinger SG, Simões RR, et al. The impact of an exercise program on quality of life in older breast cancer survivors undergoing aromatase inhibitor therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Health Qual Life. 2019;17:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1090-4.

Perry CK, Ali WB, Solanki E, Winters-Stone K. Attitudes and beliefs of older female breast cancer survivors and providers about exercise in cancer care. ONF. 2020;47(1):56–69. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.ONF.56-69

Halpern MT, Urato MP, Lines LM, Cohen JB, Arora NK, Kent EE, et al. Healthcare experience among older cancer survivors: analysis of the SEER-CAHPS dataset. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9:194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.11.005.

Mollica MA, Buckenmaier SS, Halpern MT, McNeel TS, Weaver SJ, Doose M, Kent EE. Perceptions of care coordination among older adult cancer survivors: a SEER-CAHPS study 2020. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12:446–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.09.003.

Galica J, Liu Z, Kain D, Merchant S, Booth C, Koven R, Brundage M, Haase KR. Coping during COVID-19: a mixed methods study of older cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(6):3389–3398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05929-5. Erratum in: Support Care Cancer. 2021.

Haase KR, Kain D, Merchant S, Booth C, Koven R, Brundage M, Galica J. Older survivors of cancer in the COVID-19 pandemic: reflections and recommendations for future care. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(3):461–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.11.009.

Strohschein FJ. Newton L. Fitch MI, Haase K, Puts MTE, Jin R, Loucks A, Kenis C. Optimizing care of older adults with cancer: Canadian perspectives on challenges, solutions, and the need for interprofessional collaboration. Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology National Virtual Conference, July 14-16, 2020.

Puts M, Hsu T, Szumacher E, Dawe D, Fitch M, Jones J, Fulop T, Alibhai S, Strohschein F. Never too old to learn new tricks: surveying Canadian health care professionals about learning needs in caring for older adults with cancer. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(2):71–2. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.26.4833.

Strohschein FJ, Newton L, Puts M, Jin R, Haase, K, Plante A, Loucks A, Kenis C, Fitch MI. Optimizing the care of older Canadians with cancer and their families: a statement articulating the position and contribution of Canadian oncology nurses. Can Oncol Nurs J = Revue canadienne de nursing oncologique. 2021;31(3):352–356.

Pisu M, Rocque GB, Jackson BE, Kenzik KM, Sharma P, Williams CP… Meneses K. Lay navigation across the cancer continuum for older cancer survivors: equally beneficial for Black and White survivors? J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(5):779–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2018.10.013

Krok-Schoen JL, DeSalvo J, Klemanski D, Stephens C, Noonan AM, Brill S, Lustberg MB. Primary care physicians’ perspectives of the survivorship care for older breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(2):645–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04855-5.

Krok-Schoen JL, Naughton MJ, Noonan AM, Pisegna J, DeSalvo J, Lustberg MB. Perspectives of survivorship care plans among older breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Cancer Control. 2020;27(1):1073274820917208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073274820917208.

Cohee AA, Bigatti SM, Shields CG, Johns SA, Stump T, Monahan PO, Champion VL. Quality of life in partners of young and old breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(6):491–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000556.

Kadambi S, Loh KP, Dunne R, Magnuson A, Maggiore R, Zittel J, Mohile S. Older adults with cancer and their caregivers - current landscape and future directions for clinical care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(12):742–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0421-z.

Van Den Noortgate N, Van Humbeeck L. Medical assistance in dying and older persons in Belgium: trends, emerging issues and challenges. Age Ageing. 2021;50(1):68–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa116.

Beuthin R, Bruce A, Scaia M. Medical assistance in dying (MAiD): Canadian nurses’ experiences. Nurs Forum. 2018;53:511–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12280. A Canadian descriptive narrative inquiry examining nurses’ experiences in the first six months of MAiD legalization, highlighting professional impacts of, and the importance of, open and non-judgemental communication with and between patients, families and the multidisciplinary healthcare team.

Selby, D, Bean, S, Isenberg-Grzeda, E, Bioethics, B, & Nolen, A. Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD): A Descriptive study from a Canadian tertiary care hospital. Am J Hospice Palliat Care. 2020;37(1):58–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119859844. A retrospective chart review was conducted to better understand the nature of MAiD requests in a Canadian healthcare institution, finding similarities with requests to other jurisdictions, and indicating that earlier assessments and more careful monitoring would be beneficial for this group at high risk for loss of capacity.

Blanke C, LeBlanc M, Hershman D, Ellis L, Meyskens F. (2017). Characterizing 18 years of the death with dignity act in Oregon. JAMA Oncol 2017;3(10):1403–1406. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0243. This analysis of publicly available data illuminates how MAiD in the USA is enacted and corroborates how cancer is the prevalent diagnosis of those choosing this option.

Emanuel IJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Unwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316:79–90. Comprehensive review of practices across Europe and North America with extensive data on differing approaches and experiences.

Health Canada. Second Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada: 2020. Ottawa, ON; June 2021. Accessed December 2, 2021 from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/medical-assistance-dying/annual-report-2020/annual-report-2020-eng.pdf

Selby D, Bean S. Oncologists communicating with patients about assisted dying. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2019;13(1):59–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000411. A review of recent literature regarding MAiD and communication revealed key themes of perceived barriers and benefits, including the importance of pragmatic and proactive approaches o develop and support best practices

Chandhoke G, Pond G, Levine O, Oczkowski S. Oncologists and medical assistance in dying: where do we stand? Results of a national survey of Canadian oncologists. Curr Oncol (Toronto, Ont.), 2020;27(5):263–269. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.27.6295. An overview of survey finding to better understand Canadian oncologists’ experiences with MAiD, in which 70% of respondents received MAiD requests, supporting calls for standardized guidelines to safeguard equitable access for oncology patients.

Li M, Shapiro GK, Klein R, et al. Medical Assistance in Dying in patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a mixed methods longitudinal study protocol. BMC Palliat Care, 2021;117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00793-4. This Canadian study is aimed to excavate the prevalence and determinants of depression and demoralization and how these states influence desire for death and MAiD requests, pointing to the importance of appropriate access and further consideration as the legislation for MAiD is broadening.

Jackson ML. Transitional Care: methods and processes for transitioning older adults with cancer in a post-acute setting. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(6):37–41. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.CJON.S2.37-41.

Suva G, Penney T, McPherson CJ. Medical assistance in dying: a scoping review to inform nurses’ practice. J Hospice Palliat Nurs. 2019;21(1):46–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000486.

Pesut B, Thorne S, Schiller C, Greig M, Roussel J, Tishelman C. (2020). Constructing good nursing practice for medical assistance in dying in Canada: an interpretive descriptive study. Glob QualNurs Res. 2020;7:2333393620938686https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393620938686. The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore ‘good nursing practice’ in the context of MAiD to humanize a somewhat medicalized experience, which includes establishing relationships, planning and supporting the family and underscores the need for best practice guidelines development.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Older adult oncology (Version 1.2021). 2021. Available from: www.nccn.org. Accessed 2 Jan 2022.

Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, Schonberg MA, Boyd CM, Burhenn PS, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2326–47.

Extermann M, Brain E, Canin B, Cherian MN, Cheung K-L, de Glas N, et al. Priorities for the global advancement of care for older adults with cancer: an update of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology Priorities Initiative. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(1):e29–36.

Puts M, Strohschein F, Oldenmenger W, Haase K, Newton L, Fitch M, et al. Position statement on oncology and cancer nursing care for older adults with cancer and their caregivers of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology Nursing and Allied Health Interest Group, the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology Oncology & Aging Special Interest Group, and the European Oncology Nursing Society. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12(7):1000–4.

Scotté F, Bossi P, Carola E, Cudennec T, Dielenseger P, Gomes F, et al. Addressing the quality of life needs of older patients with cancer: a SIOG consensus paper and practical guide. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(8):1718–26.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Geriatric Oncology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fitch, M.I., Nicoll, I., Newton, L. et al. Challenges of Survivorship for Older Adults Diagnosed with Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 24, 763–773 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-022-01255-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-022-01255-7