Abstract

Purpose of review

Despite tremendous potential for public health impact and continued investments in development and evaluation, it is rare for eHealth behavioral interventions to be implemented broadly in practice. Intervention developers may not be planning for implementation when designing technology-enabled interventions, thus creating greater challenges for real-world deployment following a research trial. To facilitate faster translation to practice, we aimed to provide researchers and developers with an implementation-focused approach and set of design considerations as they develop new eHealth programs.

Recent findings

Using the Accelerated Creation-to-Sustainment model as a lens, we examined challenges and successes experienced during the development and evaluation of four diverse eHealth HIV prevention programs for young men who have sex with men: Keep It Up!, Harnessing Online Peer Education, Guy2Guy, and HealthMindr. HIV is useful for studying eHealth implementation because of the substantial proliferation of diverse eHealth interventions with strong evidence of reach and efficacy and the responsiveness to rapid and radical disruptions in the field. Rather than locked-down products to be disseminated, eHealth interventions are complex sociotechnical systems that require continual optimization, vigilance to monitor and troubleshoot technological issues, and decision rules to refresh content and functionality while maintaining fidelity to core intervention principles. Platform choice and sociotechnical relationships (among end users, implementers, and the technology) heavily influence implementation needs and challenges. We present a checklist of critical implementation questions to address during intervention development.

Summary

In the absence of a clear path forward for eHealth implementation, deliberate design of an eHealth intervention’s service and technological components in tandem with their implementation plans is critical to mitigating barriers to widespread use. The design considerations presented can be used by developers, evaluators, reviewers, and funders to prioritize the pragmatic scalability of eHealth interventions in research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- (A/Y)MSM:

-

(adolescent/young) men who have sex with men

- ACTS:

-

Accelerated Creation-to-Sustainment (model)

- CBO:

-

community-based organization

- C-POL:

-

Community Popular Opinion Leader (model)

- EBI:

-

evidence-based intervention

- G2G:

-

Guy2Guy

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- HM:

-

HealthMindr

- HOPE:

-

Harnessing Online Peer Education

- IMB:

-

Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills (model)

- KIU!:

-

Keep It Up!

- PrEP:

-

pre-exposure prophylaxis

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trial

- STI:

-

sexually transmitted infection

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Oh H, Rizo C, Enkin M, Jadad A. What is eHealth (3): a systematic review of published definitions. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(1):e1. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7.1.e1.

Bennett GG, Glasgow RE. The delivery of public health interventions via the Internet: actualizing their potential. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:273–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100235.

Mohr DC, Burns MN, Schueller SM, Clarke G, Klinkman M. Behavioral intervention technologies: evidence review and recommendations for future research in mental health. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(4):332–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.03.008.

Bailey J, Mann S, Wayal S, Hunter R, Free C, Abraham C, et al. Sexual health promotion for young people delivered via digital media: a scoping review. Public Health Res. 2015;3(13). https://doi.org/10.3310/phr03130.

Ybarra ML, Bull SS. Current trends in Internet- and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):201–7.

Mohr DC, Schueller SM, Riley WT, Brown CH, Cuijpers P, Duan N, et al. Trials of intervention principles: evaluation methods for evolving behavioral intervention technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(7):e166. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4391.

Schueller SM, Munoz RF, Mohr DC. Realizing the potential of behavioral intervention technologies. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(6):478–83.

Brown CH, Mohr DC, Gallo CG, Mader C, Palinkas L, Wingood G, et al. A computational future for preventing HIV in minority communities: how advanced technology can improve implementation of effective programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 1):S72–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829372bd.

Noar SM, Pierce LB, Black HG. Can computer-mediated interventions change theoretical mediators of safer sex? A meta-analysis. Hum Commun Res. 2010;36(3):261–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01376.x.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–7.

Muessig KE, Nekkanti M, Bauermeister J, Bull S, Hightow-Weidman LB. A systematic review of recent smartphone, Internet and Web 2.0 interventions to address the HIV continuum of care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(1):173–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-014-0239-3.

Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Bauermeister J, Zhang C, LeGrand S. Youth, technology, and HIV: recent advances and future directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(4):500–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-015-0280-x.

Noar SM. Computer technology-based interventions in HIV prevention: state of the evidence and future directions for research. AIDS Care. 2011;23(5):525–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2010.516349.

Kemp CG, Velloza J. Implementation of eHealth interventions across the HIV care cascade: a review of recent research. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15:403–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0415-y.

Brownson RC, Jacobs JA, Tabak RG, Hoehner CM, Stamatakis KA. Designing for dissemination among public health researchers: findings from a national survey in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1693–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301165.

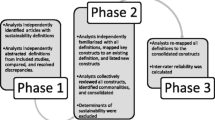

• Mohr DC, Lyon AR, Lattie EG, Reddy M, Schueller SM. Accelerating digital mental health research from early design and creation to successful implementation and sustainment. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(5):e153. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7725 This paper describes the Accelerated Creation-to-Sustainment (ACTS) model, a process model for producing functioning technology-enabled services that are sustainable in a real-world treatment settings. Its deconstruction of eHealth interventions into service, technology, and implementation components forms the framework for the current study.

Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearb Med Inform. 2000;1:65–70.

Allison S, Bauermeister JA, Bull S, Lightfoot M, Mustanski B, Shegog R, et al. The intersection of youth, technology, and new media with sexual health: moving the research agenda forward. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):207–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.012.

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):337–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chorpita BF. Disruptive innovations for designing and diffusing evidence-based interventions. Am Psychol. 2012;67(6):463–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028180.

Bell SG, Newcomer SF, Bachrach C, Borawski E, Jemmott JB 3rd, Morrison D, et al. Challenges in replicating interventions. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(6):514–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.005.

Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-2-42.

Neumann MS, Sogolow ED. Replicating effective programs: HIV/AIDS prevention technology transfer. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(5 Suppl):35–48.

Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci. 2013;8:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-117.

Henny KD, Wilkes AL, McDonald CM, Denson DJ, Neumann MS. A rapid review of eHealth interventions addressing the continuum of HIV care (2007-2017). AIDS Behav. 2018;22(1):43–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1923-2.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among youth. 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/. Accessed 18 Nov 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: HIV among Gay and Bisexual Men. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-msm-508.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevention in the United States: New opportunities, new expectations. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2015.

Mustanski B, Newcomb M, Du Bois SN, Garcia SC, Grov C. HIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. J Sex Res. 2011;48(2–3):218–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.558645.

Barrett B, Bound AM. A critical discourse analysis of no promo Homo policies in US schools. Educ Stud. 2015;51(4):267–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2015.1052445.

D’Amico E, Julien D. Disclosure of sexual orientation and gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths’ adjustment: associations with past and current parental acceptance and rejection. J GLBT Family Stud. 2012;8(3):215–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2012.677232.

Kuper LE, Coleman BR, Mustanski BS. Coping with LGBT and racial-ethnic-related stressors: a mixed-methods study of LGBT youth of color. J Res Adolesc. 2014;24(4):703–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12079.

Swendeman D, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Innovation in sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevention: internet and mobile phone delivery vehicles for global diffusion. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(2):139–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e328336656a.

Kelly JA, Spielberg F, McAuliffe TL. Defining, designing, implementing, and evaluating phase 4 HIV prevention effectiveness trials for vulnerable populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(Suppl 1):S28–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605c77.

Rietmeijer CA. Risk reduction counselling for prevention of sexually transmitted infections: how it works and how to make it work. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(1):2–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2006.017319.

Solomon J, Card JJ, Malow RM. Adapting efficacious interventions: advancing translational research in HIV prevention. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(2):162–94.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men - National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 20 U.S. cities, 2014. 2016.

Harper GW, Bruce D, Serrano P, Jamil OB. The role of the Internet in the sexual identity development of gay and bisexual male adolescents. In: Hammack PL, Cohler BJ, editors. The story of sexual identity: narrative perspectives on the gay and lesbian life course. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. p. 297–326.

Macapagal K, Moskowitz DA, Li DH, Carrion A, Bettin E, Fisher CB, et al. Hookup app use, sexual behavior, and sexual health among adolescent men who have sex with men in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(6):708–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.01.001.

Lenhart A. Teen, social media and technology overview 2015. Pew Research Center; 2015.

Garofalo R, Herrick A, Mustanski BS, Donenberg GR. Tip of the iceberg: young men who have sex with men, the Internet, and HIV risk. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1113–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.075630.

Bolding G, Davis M, Hart G, Sherr L, Elford J. Where young MSM meet their first sexual partner: the role of the Internet. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(4):522–6.

Paul JP, Ayala G, Choi KH. Internet sex ads for MSM and partner selection criteria: the potency of race/ethnicity online. J Sex Res. 2010;47(6):528–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903244575.

Chiasson MA, Hirshfield S, Rietmeijer C. HIV prevention and care in the digital age. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S94–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fcb878.

Mustanski B, Lyons T, Garcia SC. Internet use and sexual health of young men who have sex with men: a mixed-methods study. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(2):289–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9596-1.

Bauermeister JA, Pingel ES, Jadwin-Cakmak L, Harper GW, Horvath K, Weiss G, et al. Acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a tailored online HIV/STI testing intervention for young men who have sex with men: the Get Connected! program. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1860–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1009-y.

Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Monahan C, Gratzer B, Andrews R. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an online HIV prevention program for diverse young men who have sex with men: the Keep It Up! intervention. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2999–3012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0507-z.

Greene GJ, Madkins K, Andrews K, Dispenza J, Mustanski B. Implementation and evaluation of the Keep It Up! online HIV prevention intervention in a community-based setting. AIDS Educ Prev. 2016;28(3):231–45. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2016.28.3.231.

Guse K, Levine D, Martins S, Lira A, Gaarde J, Westmorland W, et al. Interventions using new digital media to improve adolescent sexual health: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(6):535–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.014.

Noar SM, Willoughby JF. eHealth interventions for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2012;24(8):945–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.668167.

Gabarron E, Wynn R. Use of social media for sexual health promotion: a scoping review. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:32193. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.32193.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chovnick G. The past, present, and future of HIV prevention: integrating behavioral, biomedical, and structural intervention strategies for the next generation of HIV prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:143–67. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153530.

Rausch DM, Grossman CI, Erbelding EJ. Integrating behavioral and biomedical research in HIV interventions: challenges and opportunities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 1):S6–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e318292153b.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Supported activities: prioritizing high impact HIV prevention. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/programresources/healthdepartments/supportedactivities.html. Accessed 18 Nov 2018.

Kaiser Family Foundation. U.S. Federal Funding for HIV/AIDS: Trends Over Time. 2017. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/u-s-federal-funding-for-hivaids-trends-over-time/. Accessed 18 Nov 2018.

•• Aarons GA, Sklar M, Mustanski B, Benbow N, Brown CH. “Scaling-out” evidence-based interventions to new populations or new health care delivery systems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0640-6 This paper provides a conceptual framework for determining what new empirical evidence is required for an intervention to retain its evidence-based standard when adapting to a new population, new delivery context, or both. It also describes when an adaptation can “borrow strength” from prior evidence of impact.

Mohr DC, Weingardt KR, Reddy M, Schueller SM. Three problems with current digital mental health research . . . and three things we can do about them. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(5):427–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600541.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Williams SS, Malloy TE. Empirical tests of an information-motivation-behavioral skills model of AIDS-preventive behavior with gay men and heterosexual university students. Health Psychol. 1994;13(3):238–50.

Fisher CM. Adapting the information-motivation-behavioral skills model: predicting HIV-related sexual risk among sexual minority youth. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39(3):290–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198111406537.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: strategies for improving public health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 40–70.

Mustanski B, Madkins K, Greene GJ, Parsons JT, Johnson BA, Sullivan P, et al. Internet-based HIV prevention with at-home sexually transmitted infection testing for young men having sex with men: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial of Keep It Up! 2.0. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(1):e1. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.5740.

Mustanski B, Parsons JT, Sullivan PS, Madkins K, Rosenberg E, Swann G. Biomedical and behavioral outcomes of Keep It Up!: an eHealth HIV prevention program RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(2):151–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.026.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evidence of HIV treatment and viral suppression in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/art/cdc-hiv-art-viral-suppression.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2018.

Gershon R, Rothrock NE, Hanrahan RT, Jansky LJ, Harniss M, Riley W. The development of a clinical outcomes survey research application: assessment center. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(5):677–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9634-4.

Turner-McGrievy GM, Hales SB, Schoffman DE, Valafar H, Brazendale K, Weaver RG, et al. Choosing between responsive-design websites versus mobile apps for your mobile behavioral intervention: presenting four case studies. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(2):224–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-016-0448-y.

Du Bois SN, Johnson SE, Mustanski B. Examining racial and ethnic minority differences among YMSM during recruitment for an online HIV prevention intervention study. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1430–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0058-0.

Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Jones L, et al. An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044215.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Free Press; 2003.

Jaganath D, Gill HK, Cohen AC, Young SD. Harnessing Online Peer Education (HOPE): integrating C-POL and social media to train peer leaders in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2012;24(5):593–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2011.630355.

Young SD, Cumberland WG, Lee S-J, Jaganath D, Szekeres G, Coates T. Social networking technologies as an emerging tool for HIV prevention A: cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):318–24.

Young SD, Cumberland WG, Nianogo R, Menacho LA, Galea JT, Coates T. The HOPE social media intervention for global HIV prevention in Peru: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(1):e27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(14)00006-X.

Young SD. Social media technologies for HIV prevention study retention among minority men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1625–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0604-z.

Young SD, Koussa M, Lee J, Gill K, Perez H, Gelberg L, Heinzerling K. Feasibility of a social media/online community support group intervention among chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. J Addict Dis. in press.

Young SD, Heinzerling K. The Harnessing Online Peer Education (HOPE) intervention for reducing prescription drug abuse: a qualitative study. J Subst Use. 2017;22(6):592–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2016.1271039.

Young SD. Stick with it: a scientifically proven process for changing your life--for good. New York, NY: Harper; 2017.

Young SD, Jaganath D. Feasibility of using social networking technologies for health research among men who have sex with men: a mixed methods study. Am J Mens Health. 2014;8(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988313476878.

Ybarra ML, Prescott TL, Philips GL 2nd, Bull SS, Parsons JT, Mustanski B. Iteratively developing an mHealth HIV orevention program for sexual minority adolescent men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(6):1157–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1146-3.

Ybarra ML, Prescott TL, Phillips GL, 2nd, Bull SS, Parsons JT, Mustanski B. Pilot RCT results of an mHealth HIV prevention program for sexual minority male adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2999.

Gilead Sciences Inc. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves expanded indication for Truvada® (emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) for reducing the risk of acquiring HIV-1 in adolescents. Business Wire; 2018.

Gallo C, Moran K, Brown CH, Mustanski B. Optimizing HIV prevention mHealth interventions by measuring linguistic alignment. 10th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation; Arlington, VA. 2017.

Sullivan PS, Driggers R, Stekler JD, Siegler A, Goldenberg T, McDougal SJ, et al. Usability and acceptability of a mobile comprehensive HIV prevention app for men who have sex with men: a pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(3):e26. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.7199.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall: Engelwood Cliffs, NJ; 1986.

Goldenberg T, McDougal SJ, Sullivan PS, Stekler JD, Stephenson R. Building a mobile HIV prevention app for men who have sex with men: an iterative and community-driven process. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2015;1(2):e18. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.4449.

Goldenberg T, McDougal SJ, Sullivan PS, Stekler JD, Stephenson R. Preferences for a Mobile HIV prevention app for men who have sex with men. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2014;2(4):e47. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.3745.

Sullivan PS, Sineath C, Kahle EST. Awareness, willingness, and use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among a national sample of US men who have sex with men. Amsterdam: AIDS Impact; 2015.

Siegler AJ, Wirtz S, Weber S, Sullivan PS. Developing a web-based geolocated directory of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis-providing clinics: the PrEP locator protocol and operating procedures. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(3):e58. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.7902.

Mustanski B, Feinstein BA, Madkins K, Sullivan P, Swann G. Prevalence and risk factors for rectal and urethral sexually transmitted infections from self-collected samples among Young men who have sex with men participating in the Keep It Up! 2.0 randomized controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(8):483–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000636.

Siegler AJ, Mayer KH, Liu AY, Patel RR, Ahlschlager LM, Kraft CS, et al. Developing and assessing the feasibility of a home-based PrEP monitoring and support program. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;68:501–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy529.

Whittaker R. Key issues in mobile health and implications for New Zealand. Health Care and Informatics Review Online. 2012;16(2):2–7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention. 2019. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/complete.html. Accessed 12 Mar 2019.

Collins CB Jr, Wilson KM. CDC's dissemination of evidence-based behavioral HIV prevention interventions. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(2):203–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-011-0048-9.

Collins LM, Dziak JJ, Kugler KC, Trail JB. Factorial experiments: efficient tools for evaluation of intervention components. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):498–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.021.

Murphy SA. An experimental design for the development of adaptive treatment strategies. Stat Med. 2005;24(10):1455–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2022.

Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5 Suppl):S112–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Kegeles SM, Rebchook G, Tebbetts S, Arnold E, Team T. Facilitators and barriers to effective scale-up of an evidence-based multilevel HIV prevention intervention. Implement Sci. 2015;10:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0216-2.

Labrique AB, Vasudevan L, Kochi E, Fabricant R, Mehl G. mHealth innovations as health system strengthening tools: 12 common applications and a visual framework. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2013;1(2):160–71. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00031.

Eysenbach G, Group C-E. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e126. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1923.

• Agarwal S, Lefevre AE, Labrique AB. A call to digital health practitioners: new guidelines can help improve the quality of digital health evidence. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(10):e136. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.6640 This paper presents the World Health Organization’s mHealth Evidence Reporting and Assessment (mERA) checklist of 16 core mHealth items and 29 methodology items to ensure comprehensiveness and quality of reporting on critical aspects of digital health program effectiveness research.

Bartholomew Eldredge LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Fernandez ME. Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. Fourth edition. Ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley; 2016.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of our Ce-PIM colleagues and community advisors for their contributions.

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Institutes of Health and other sponsors. Development, evaluation, and implementation of Keep It Up! was previously sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (R34MH079714, Mustanski), National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA035145, Mustanski), Chicago Department of Public Health, and ViiV Healthcare. Harnessing Online Peer Education was previously sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH090884, Young) and UCLA Center for AIDS Research (P30AI028697, Zack), with ongoing sponsorship from the former (R01MH106415, Young). Guy2Guy was previously sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH096660, Mustanski & Ybarra), with ongoing work supported by the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (P30AI117943, D’Aquila) and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (SRG-0-110-15, Pisani). HealthMindr was previously sponsored by the MAC AIDS Fund, Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30AI050409, Del Rio), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA045612, Sullivan).

This manuscript was a product of a workgroup on eHealth interventions formed through the Center for Prevention Implementation Methodology for Drug Abuse and HIV (Ce-PIM), which is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P30DA027828, Brown & Mustanski). This work was also supported by the Keep It Up! 3.0 grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and Office of Disease Prevention at the National Institutes of Health (R01MH118213, Mustanski), as well as an individual postdoctoral fellowship grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (F32DA046313, Morgan). The sponsors had no involvement in the conduct of the research or the preparation of the manuscript. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DL led the analysis and writing of the manuscript. BM, SY, CG, and PS provided details about the four interventions and initial drafts of those sections. CHB provided guidance on implementation science. BM provided guidance on eHealth. EM provided review and feedback. All authors contributed significantly to conceptually framing the manuscript and its conclusions, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Sullivan reports grants and personal fees from NIH, grants and personal fees from CDC, grants and personal fees from Gilead Sciences outside the submitted work.

Dr. Li reports grants from National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Brown reports grants from National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Mustanski reports grants from National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Morgan reports grants from National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Gallo has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Young has nothing to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Implementation Science

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D.H., Brown, C.H., Gallo, C. et al. Design Considerations for Implementing eHealth Behavioral Interventions for HIV Prevention in Evolving Sociotechnical Landscapes. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 16, 335–348 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-019-00455-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-019-00455-4