Abstract

The current imaginary mock-crime study examined innocent interviewees’ (N = 128) planned counter-interrogation strategies and their willingness to disclose critical information as a function of (a) the type of secondary act (irrelevant to the crime under investigation) they imagined having executed at the crime scene (lawful act vs. unlawful act) and (b) the presence of suspicion directed towards the interviewees (suspicion vs. no suspicion). Results show that, to be honest, was the most frequently reported strategy among lawful as well as unlawful act participants. In contrast, none of the lawful act participants reported the strategy to be deceptive, whereas 35.9% of the unlawful act participants did. When no suspicion (vs. suspicion) was directed towards unlawful act participants, they were less willing to voluntarily share critical information on their true intentions at the crime scene. Consequently, seemingly easy “no suspicion” situations appear to promote the application of more deceptive and evasive behavior in unlawful act interviewees and might therefore put them at risk of being wrongfully assessed as guilty of the crime under investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last decade, the scientific exploration of suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies has gained importance within the field of deception detection research. This is partially due to the insight that knowledge on the differences in suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies is a key component of developing and implementing effective interviewing approaches (Granhag et al. 2015). As defined by Clemens (2013), counter-interrogation strategies are tactics applied by suspects to successfully withstand an interviewing situation and appear convincingly.

To date, research on suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies has primarily focussed on the difference between completely innocent suspects and guilty suspects (e.g., Hartwig et al. 2007; Vrij et al. 2010). Empirical research has shown that innocent suspects are usually eager to openly and honestly provide the information they hold (including potentially self-incriminating information) (e.g., Hartwig et al. 2007; for a more detailed account on the theoretical underpinnings, see Granhag et al. 2015; Kassin and Norwick 2004; Lerner 1980; Savitsky and Gilovich 2003). This is due to the fact that they want the interviewer to know what they know, namely that they did not commit the crime under investigation. These strategies of openness and honesty are referred to as forthcoming strategies.

In contrast, guilty suspects possess exclusive crime-related knowledge and they usually do not want the interviewer to know it. Especially when it is uncertain which critical information the interviewer holds, this information can be considered an aversive stimulus to guilty suspects (see Granhag and Hartwig 2008 for a more detailed account). Research shows that guilty suspects in these situations tend to apply evasive strategies, such as withholding or denying crime-related information (e.g., Strömwall et al. 2006; Strömwall and Willén 2011). However, in some studies, more forthcoming strategies (e.g., tell a detailed story) were reported by guilty suspects (e.g., Hartwig et al. 2007; Strömwall and Willén 2011). These partially differing results can be explained by research suggesting that guilty suspects sometimes use strategic self-presentation methods that are deliberately aimed at making a truthful impression during the interview (e.g., Burgoon et al. 1999; Hines et al. 2010; Vrij et al. 2010).

A group of suspects, which has been almost completely disregarded to date (for the few exceptions see Clemens and Grolig 2019; Colwell et al. 2018), are suspects who are innocent of the crime under investigation but have executed a different unlawful act or committed a social transgression (in the following “unlawful act suspects”). This is surprising considering that in real-life situations it is possible that suspects, who are innocent of a crime (e.g., a murder), were present at/close to the crime scene for a different unlawful reason or activity (e.g., selling/buying drugs) around the time the crime occurred. Colwell et al. (2018) report two real-life cases in which yet another scenario is outlined, namely that a person, who did not commit the crime under investigation, was involved in a transgressive/unlawful interaction with the victim and consequently cannot be considered “completely innocent.”

The limited research on this specific group of suspects has shown that unlawful act suspects–compared to the completely innocent suspects (in the following “lawful act suspects”)–apply forthcoming strategies (e.g., openness and honesty) less frequently. Instead, evasive and conscious self-presentation strategies, which are typical for guilty suspects, are applied more frequently by unlawful compared to lawful act suspects (Clemens and Grolig 2019; Colwell et al. 2018). The increase in typical “guilty” strategies could be due to the fact that their reason for being at the crime scene/or their crime-unrelated actions/intentions were unlawful. Consequently, the interview situation and the questions about the crime or the crime scene can represent threatening stimuli to unlawful act suspects (cf. reasoning for guilty suspects) and trigger evasive and conscious self-presentational strategies.

Apart from their involvement in the crime (suspect-related factor), suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies can also be moderated by interview-related factors. One such factor is the degree of suspicion directed toward the suspect (Granhag et al. 2015). Multiple studies have assessed the impact of guilt presumption on interviewers’ behavior (e.g., the questions they choose to ask). Beyond that, some of these studies have examined the effect of guilt-presumptive interviewers on the (non)verbal behavior of innocent and guilty suspects and on the perception of this behavior (e.g., Granhag et al. 2009; Hill et al. 2008; Kassin et al. 2003; Portnoy et al. 2019). Hill et al., as well as Kassin et al., found that guilt-presumptive questioning by the interviewer (vs. innocent-presumptive or neutral questioning) made suspects appear more defensive. Although Kassin et al.’s study showed that innocent suspects’ statements generally were perceived as more plausible than guilty suspects’ statements, Hill et al. showed a decrease in the perceived plausibility of innocent mock suspects’ statements when guilt-presumptive (vs. neutral) questions were asked. Resulting in innocent (vs. guilty) suspects being perceived as significantly less plausible when answering guilt-presumptive questions.

In contrast to the findings of Hill et al. (2008) and Kassin et al. (2003), which applied to assessments of participants and statements (level of defensiveness and plausibility), Portnoy et al. (2019) examined the actual verbal behavior of innocent suspects. Specifically, they examined the number of correct details and accuracy rates of the information provided in their alibis. However, the authors did not find a significant effect of guilt presumption. On the one hand, Portnoy and colleagues explain these divergent findings, beyond other things, with methodological differences between their study and the studies of Hill et al. and Kassin et al. On the other hand, they point out the fact that just because an interviewee appears defensive (= judgment by an observer) (Hill et al. 2008; Kassin et al. 2003), it does not necessarily mean that the interviewee provides less correct or complete information (= verbal behavior).

Granhag et al. (2009) examined in their imaginary mock-crime study the effect of informing guilty suspects on the degree of suspicion directed towards them on their counter-interrogation strategies (i.e., the level of critical information they intended to disclose). Two different groups of guilty suspects (naïveFootnote 1 vs. experiencedFootnote 2) and two different degrees of suspicion (low vs. high) were compared. It was found that the high suspicion (vs. low suspicion) condition motivated naïve (but not experienced) guilty suspects to report more critical information. Consequently, it was argued that naïve guilty suspects in the high degree of suspicion condition actively worked for convincing the interrogator of their innocence and therefore–as a deliberate act of self-presentation–intended to disclose a relatively high number of critical information. However, this study did not include a sample of innocent suspects. Thus, it is unknown which effect different degrees of suspicion have on (a) the counter-interrogation strategies of completely innocent suspects (lawful act suspects) and (b) the amount of critical information they are willing to disclose. Moreover, it is unknown how completely innocent suspects (lawful act suspects) differ from innocent suspects who have executed a different unlawful act (unlawful act suspects). The current study addresses these gaps in knowledge.

Present Study

The present study is an imaginary mock-crime study in which participants were asked to read a written scenario and to imagine executing certain actions (detailed description below). The study aims to investigate differences in the planned counter-interrogation strategies and the willingness to disclose critical information of different groups of interviewees who are innocent of a mock crime. By critical information, we mean information on suspects’ actions and intentions at the crime scene. Specifically, we examine the extent to which these variables are moderated by (a) the type of secondary act (irrelevant to the crime under investigation) participants imagined having executed at the crime scene (lawful act vs. unlawful act) and (b) the presence of suspicion directed towards the participants (suspicion vs. no suspicion).Footnote 3 Consequently, the study will address the following questions:

-

1.

As an indirect replication of the findings of Clemens and Grolig (2019): Do the planned counter-interrogation strategies of unlawful act participants differ from those of lawful act participants?

-

2.

Do the planned counter-interrogation strategies of participants who are under suspicion differ from those participants who are under no suspicion?

-

3.

Do unlawful act participants differ from lawful act participants in the amount of critical information they intend to disclose?

-

4.

Do participants in the suspicion condition differ from participants in the no suspicion condition in the amount of critical information they intend to disclose?

-

5.

How does the presence of suspicion (suspicion vs. no suspicion) influence the amount of critical information lawful and unlawful act participants intend to disclose?

Based on the theoretical reasoning and as an indirect replication of the studies by Clemens and Grolig (2019) and Colwell et al. (2018), we expected that unlawful act participants (vs. lawful act participants) would report typical forthcoming strategies (i.e., openness and honesty) less frequently (hypothesis 1a), evasive strategies more frequently (hypothesis 1b), and self-presentation strategies more frequently (hypothesis 1c).

It was expected that participants in the suspicion condition would differ in their reported strategies from participants in the no suspicion condition (hypothesis 2). Due to the overall lack of theoretical and empirical knowledge on the effect of suspicion on interviewees’ counter-interrogation strategies, we refrained from making any specific predictions for this hypothesis.

Furthermore, we expected unlawful act participants to be less willing to disclose critical information than lawful act participants (hypothesis 3a). As the sample in the current study consisted of people from the general population (see results for “naïve suspects” in Granhag et al. 2009), it was expected that participants in the suspicion condition would be more willing to disclose critical information than participants in the no suspicion condition (hypothesis 3b). Concerning the effects of the suspicion directed towards the suspects, we predicted that there would be a Presence of Suspicion (suspicion vs. no suspicion) × Act (lawful vs. unlawful) interaction (hypothesis 3c) in terms of suspects’ willingness to disclose critical information. Due to the inconclusive empirical findings and the overall lack of theoretical and empirical knowledge on the interrelation of these two variables, we refrained from making any predictions on the specific direction of the interaction.

Method

Participants and Design

The current study used an imaginary mock-crime scenario. We employed a 2 (Act: lawful vs. unlawful) × 2 (Presence of Suspicion: suspicion vs. no suspicion) between-group design. Half of the participants were asked to imagine that they had executed a lawful act (irrelevant to the crime under investigation) at a place, which later turned out to be the crime scene (lawful act participants, n = 64). The other half were asked to imagine that they had executed an unlawful act (also irrelevant to the crime under investigation) at the same place (unlawful act participants, n = 64). Furthermore, two presence of suspicion conditions (suspicion vs. no suspicion) were used. The participants were randomly assigned to the four cells.

Based on this design, the study included 128 adultsFootnote 4 (96 female, 30 male, 2 other; Mage = 24.45 years, SDage = 8.07). The vast majority of the sample (92.97%) was undergraduate students at Kiel University (Germany), 6.25% were employees, and 0.78% defined their occupation as “other.” As compensation, each participant could choose between 1.5 credit hours (only eligible for psychology students) or 10 euros. Before the experiment started, all participants were asked to sign an informed consent. It was clearly stated that participation is strictly voluntary, and withdrawal is possible at any time during the experiment without penalty.

Procedure

Scenario

The scenario started with the participants reading a story, which they were asked to mentally put themselves into. Simultaneously, participants listened to an audio recording via headphones of the same story read to them.Footnote 5 Participants were asked to imagine going to a local shopping mall and entering a department store. Half of them were asked to imagine committing a lawful act, which was to stroll through the store, go to the book section, and reach out for a book from the adventure books section that they were interested in. To be able to do so, they had to imagine brushing a grey backpack aside, which was standing in their way. Finally, they had to imagine leaving the store and the mall without buying anything.

The other half of the participants were asked to imagine committing an unlawful act, namely that they had lost their smartphone and urgently needed a new one. Through a friend, they received the phone number of a dealer who was selling a smartphone, which was released to the market just the previous year, for just 50 euros. This offer seemed rather dubious, but the participant is asked to imagine deciding to purchase the smartphone anyway as s/he needed a new one and did not want to spend too much money. The participants imagined that the dealer informed them that he would deposit the smartphone on a shelf in the adventure books section, which they had to find, and then, in return, had to deposit the 50 euros at the same place in which they found the smartphone. Unlawful act participants as well had to imagine brushing a grey backpack aside, as it was standing in their way when they tried to look for the smartphone. After finding the phone and putting it in their pocket, the participants imagined depositing the money and leaving the store and the mall. Subsequently, all participants were asked to answer on a 7-point Likert scale to what extent they perceived the imagined act as illegal (1 = not at all to 7 = very much).

The Planning of the Counter-Interrogation Strategies

Next, participants were asked to imagine that one week had passed and that they received a letter from the police informing them that 200 euros were stolen from a grey backpack from the store they had visited one week ago on the same day they had visited the store. Participants in the no suspicion condition were informed that the police wanted to question them simply as a possible witness (as they were in the possession of a membership card from the store in which the theft occurred, and this could indicate frequent visits to that store). Participants in the suspicion condition were informed that the police had some sort of information that pointed at them as a possible suspect. To control whether the intended manipulation was successful, all participants were asked to report on a 7-point Likert scale what their understanding of the situation was (1 = the police want to question me as a witness to 7 = the police want to question me as a suspect).

Participants then were informed that they would soon be interviewed by a mock police officer (either as a witness or as a suspect). To further strengthen the manipulation, the participants were either instructed that their goal during the interview would be to convince the interviewer of their innocence (suspicion condition) or to maintain the interviewer’s perception that they are innocent (no suspicion condition) with regard to stealing the 200 euros from the backpack. With the help of an online questionnaire tool (SoSci Survey, Leiner 2016), participants were given 10 min to plan and report (in a written free narrative) the counter-interrogation strategies they wanted to apply during the supposedly upcoming police interview.Footnote 6

Willingness to Disclose Critical Information

When the 10 min planning time was up, participants were asked to answer five questions, that referred to their whereabouts, actions and intention on the day of the crime,Footnote 7 whether they would (a) disclose that information voluntarily (scale value = 3), (b) on request (scale value = 2), or (c) not at all (scale value = 1). As we wanted a univariate measure of willingness to disclose critical information, we subsequently combined the values generated from these five items into a single scale. Since there were in total five items, we divided the sum of all five scale values by five, creating a measure of the average degree of willingness to disclose critical information (in the following “disclosure scale”). Consequently, the disclosure scale scores could also range from 1 to 3, with a value of 3 indicating that a participant reported for all five items that s/he would voluntarily disclose these pieces of information and a value of 1 indicating that s/he would deny or not mention any of the five pieces of information.

Post-Questionnaire

After answering the five questions on their willingness to disclose critical information, all participants were informed that there would not be an interview and they were directly transferred to the post-questionnaire. Participants were requested to leave the role they were previously asked to put themselves into and answer all questions from now on as participants of the experimental study. Five questions included in this questionnaire were relevant to the current study. First, participants were asked how sufficient they perceived the time they were offered for preparing for the interview (1 = not at all sufficient to 7 = absolutely sufficient). Second, participants were asked to what degree they were convinced that the announced interview would take place (1 = not at all to 7 = very). Third, participants were asked how well they could put themselves into the role they were asked to imagine (1 = not at all to 7 = very) and to what degree they were motivated to participate in the study (1 = not at all motivated to 7 = very motivated). Finally, we asked the participants to rate on a 7-point Likert scale how severe the act they were asked to imagine was, compared to the crime they were supposed to be interviewed about (1 = the act is much less severe than the crime under investigation, […], 4 = the act and the crime under investigation are equally severe, […], 7 = the act is much more severe than the crime under investigation). As the final step, all participants were thoroughly debriefed, thanked, and rewarded for their participation in the experiment.

Coding of the Counter-Interrogation Strategies

A content analysis was performed on the reported counter-interrogation strategies. First, one coder read through all strategies and created data-driven categories of strategies. Next, a second coder coded randomly chosen 25% of the strategies by following the category system. Participants reported between one and eleven strategies. The inter-rater agreement was 85.1%, Cohen’s κ = 0.84, indicating excellent agreement (for interpretation of Cohen’s kappa values see Landis and Koch 1977). The few discrepancies between the coders were resolved by discussion until an agreement was found and necessary modifications were made to the coded data. In the end, eight categories of reported strategies were identified. Based on previous research and the reasoning outlined above (e.g., Burgoon et al. 1999; Hartwig et al. 2007; Hines et al. 2010; Strömwall et al. 2006; Strömwall and Willén 2011; Vrij et al. 2010), we grouped the categories as forthcoming, evasive, or self-presentational. Three of the identified categories were considered forthcoming: (1) to be honest (“My strategy is simply to honestly tell the story as it was.”); (2) to give a detailed statement (“Give a very detailed description of everything I did.”); and (3) to suggest ideas to the interviewer of how to prove their innocence (“I’ll suggest to them that they can check the surveillance cameras that are very common in stores.”). Two of the identified categories could be considered evasive: (4) to be deceptive (i.e., to lie about and/or omit some of the critical details, “I will omit the information on the mobile phone exchange”), which was only found among unlawful act participants; and (5) reluctant information sharing (“Do not tell anything that was not asked for.”). One of the identified strategies could be considered self-presentational: (6) to make a good and truthful impression (“Stay calm and relaxed (also pay attention to body language)”; “I stay calm and do not avoid eye contact. I stay friendly.”). Beyond that, two of the identified categories of strategies could neither be clearly labeled forthcoming, evasive nor self-presentational: (7) to remind oneself of one’s innocence and consequently be more relaxed and accepting of the (interview) situation (“To make oneself aware of the fact that one is innocent in this specific situation.”; “As I did not commit a criminal action, I have nothing to fear and merely help the police to solve the theft or help the police with my statement.”); and (8) to request information about the investigation (e.g., to be informed about the reasons for the interview “I ask them how they came up with questioning me.”). Depending on how one interprets these strategies, they could indicate aware self-presentation attempts to make a better/truthful impression in the interview (e.g., Baumeister 1982; Vohs et al. 2005) or they could simply be interpreted as attempts of the interviewees to make themselves feel better, more confident, and better prepared for the upcoming interview.

The strategies that could not be sorted into any of the existing categories and were too few (reported by five or fewer participants) and diverse to constitute distinct categories of their own, were coded as Other and not further analyzed (n = 11 strategies). When participants did not follow the instruction to report the strategies they planned to employ during the upcoming interview and instead assembled all possible (and contradicting) strategy approaches (e.g., to be fully honest, to lie about some details of the imagined actions, and to lie about everything they imagined doing), these participants were excluded from the strategy analyses (n = 14).

Results

Manipulation Checks and Test Variables

We performed a t-test and found that lawful act participants perceived their act as significantly less illegal (M = 1.42, SD = 1.02) than unlawful act participants (M = 5.33, SD = 1.43, t(114.12) = −17.82, p < 0.001, d = 3.15). The results of the calculated one-sample t-tests show that both lawful act (M = 1.27, SD = 0.67, t(63) = −32.53, p < 0.001, d = −4.07) and unlawful act participants (M = 2.88, SD = 1.43, t(63) = −6.29, p < 0.001, d = −0.79) perceived the act they were asked to imagine committing as significantly less severe than the theft of the money (i.e., mean values were significantly lower than the scale value “4,” which indicated that the imagined act and the crime under investigation were perceived equally severe). Thus, it can be assumed that the manipulation of the variable “Act” was successful. For the interpretation of the effect size d for independent means, we follow the recommendations of Cohen (1988) (0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large).

After participants were informed in the written statement that the police either wanted to question them as a possible witness or a possible suspect, they were asked about what their understanding of this information was (7-point Likert scale: 1 = the police want to question me as a witness to 7 = the police want to question me as a suspect). Participants in the “suspect/suspicion” condition reported significantly higher values (M = 6.23, SD = 1.31) than participants in the “witness/no suspicion” condition (M = 1.26, SD = 0.60, t(89.61) = 27.53, p < 0.001, d = −4.88). Thus, it can be assumed that the manipulation of the variable “Presence of Suspicion” was successful.

Significant differences emerged between lawful and unlawful act participants concerning the perceived sufficiency of the time to prepare for the interview (ML = 5.80, SDL = 1.52 vs. MUL = 5.06, SDUL = 1.89, t(120.72) = 2.42, p = 0.002, d = −0.43) and concerning the degree to which they could put themselves into the role they were asked to imagine (ML = 6.27, SDL = 1.07 vs. MUL = 5.39, SDUL = 1.27, t(126) = 4.22, p < 0.001, d = −0.75). However, mean values above five (on 7-point scales) in all conditions indicate that the participants (a) perceived the time to prepare for the interview as fairly sufficient and (b) were rather able to put themselves into the role they were asked to imagine.

No significant difference emerged between lawful (M = 5.61, SD = 1.66) and unlawful act participants (M = 5.33, SD = 1.73) concerning the degree to which they were convinced that the interview would actually take place (t(126) = 0.94, p = 0.349, d = −0.17). Mean values above five (on a 7-point scale) indicate that participants were fairly convinced that the announced interview would take place.

There was no significant difference between lawful act (M = 6.31, SD = 0.89) and unlawful act participants (M = 6.02, SD = 1.22) concerning their degree of motivation (t(126) = 1.58, p = 0.117, d = −0.27). Mean values slightly higher than six (on a 7-point scale) indicate that all participants were highly motivated to perform the task.

Participants’ Self-Reported Counter-Interrogation Strategies

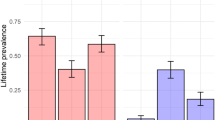

Figure 1 displays the categories of strategies that were reported by more than five participants in at least one of the four experimental conditions.Footnote 8 Strategies that were reported by five or fewer participants were sorted into the category Other and not further analyzed. The strategy to be honest was the most frequently reported strategy among lawful (no suspicion: 93.8% vs. suspicion: 90.6%) as well as unlawful act participants (no suspicion: 59.4% vs. suspicion: 53.1%). None of the lawful act participants reported the strategy to be deceptive, whereas 43.8% of the unlawful act participants in the no suspicion condition and 28.1% of the unlawful act participants in the suspicion condition did.

To test hypotheses 1a–c and 2, we calculated χ2 tests to compare the frequencies of reported strategies between lawful vs. unlawful act participants and between participants in the no suspicion vs. suspicion condition. For the goodness of fit of the two-by-two contingency tables, we used ϕ as a measure of effect size (0.1 = small effect, 0.3 = medium effect, 0.5 = large effect, see Cohen 1988, 1992).

The results for the comparisons of the two Act conditions (lawful vs. unlawful) can be seen in Fig. 2. As three forthcoming categories of strategies were identified, we applied a Bonferroni corrected significance level (0.05/3) of 0.017 for hypothesis 1a. Lawful (vs. unlawful) act participants reported the forthcoming strategies to be honest (χ2(1, N = 128) = 21.599, p < 0.001, ϕ = 0.41), to give a detailed statement (χ2(1, N = 128) = 5.680, p = 0.017, ϕ = 0.21), and to suggest ideas to the interviewer of how to prove their innocence (χ2(1, N = 128) = 7.336, p = 0.007, ϕ = 0.24), significantly more often. Consequently, we found support for hypothesis 1a.

Reported strategies of the unlawful and lawful act participants. Note: Superscripted letter “a” indicates the percentage of all mock suspects in that “Act” condition who reported this specific strategy. Each mock suspect could contribute to each strategy. For forthcoming strategies *p ≤ 0.017; for evasive strategies *p ≤ 0.025

As two evasive categories of strategies were identified, we applied a Bonferroni corrected significance level (0.05/2) of 0.025 for hypothesis 1b. The results show that unlawful (vs. lawful) act participants reported the evasive strategy to be deceptive (χ2(1, N = 128) = 28.038, p < 0.001, ϕ = 0.47) significantly more often, whereas no significant result was found for the evasive strategy of reluctant information sharing (χ2(1, N = 128) = 4.137, p = 0.042, ϕ = 0.18. These results are only partially in line with hypothesis 1b.

For the self-presentation strategy (to make a good and truthful impression) no significant difference was found between lawful and unlawful act participants (p > 0.05). Thus, hypothesis 1c was not supported.

For the two strategies, that could not be clearly labeled “forthcoming,” “evasive,” or “self-presentational” (to remind oneself of one’s innocence and consequently be more relaxed and accepting of the (interview) situation and to request information about the investigation), no significant differences occurred between lawful and unlawful act participants (Bonferroni correction 0.05/2 = 0.025).

As we did not make separate predictions for the eight different groups of strategies, we applied a Bonferroni corrected significance level (0.05/8) of 0.006. We found that participants in the suspicion (vs. no suspicion) condition reported the strategy to request information about the investigation (χ2(1, N = 128) = 15.170, p < 0.001, ϕ = 0.34) significantly more often (see Fig. 3). As for the rest of the extracted strategies, no significant differences were found between the suspicion and no suspicion condition. Thus, hypothesis 2 was only partially supported.

Reported strategies of the participants in the no suspicion and suspicion conditions. Note: Superscripted letter “a” indicates the percentage of all mock suspects in that “Suspicion” condition who reported this specific strategy. Each mock suspect could contribute to each strategy. For ambiguous strategies *p ≤ 0.006

As a secondary and exploratory step, we wanted to take a closer look at whether the frequencies of the reported strategies differ between the four experimental conditions and calculated further χ2 tests (see Fig. 1). For each of the eight categories of strategies, four comparisons of interest were calculated Footnote 9; consequently, we applied a Bonferroni corrected significance level (α/n = 0.05/32) of 0.002.

In the suspicion condition, the forthcoming strategy to be honest was significantly more often reported by lawful (vs. unlawful) act participants (χ2(1, N = 64) = 11.130, p < 0.001, ϕ = 0.42). Also, in the no suspicion condition, lawful (vs. unlawful) act participants reported the strategy to be honest significantly more often (χ2(1, N = 64) = 10.536, p = 0.001, ϕ = 0.41). No significant differences occurred for the remaining two comparisons.

In the suspicion condition, the evasive strategy to be deceptive was significantly more often reported by unlawful (vs. lawful) act participants (χ2(1, N = 64) = 10.473, p = 0.001, ϕ = 0.41). The same result occurred in the no suspicion condition (unlawful act participants > lawful act participants) (χ2(1, N = 64) = 17.920, p < 0.001, ϕ = 0.53). No significant differences occurred for the remaining two comparisons.

However, for the majority of the extracted categories of strategies (i.e., to give a detailed statement, to suggest ideas to the interviewer of how to prove their innocence, reluctant information sharing, to make a good and truthful impression, to remind oneself of one’s innocence and consequently be more relaxed and accepting of the (interview) situation, and to request information about the investigation), no significant differences occurred between the four experimental conditions.

Critical Information

A two-way ANOVA, with Act and Presence of Suspicion as independent variables and the values of the disclosure scale as the dependent variable, revealed that lawful act participants planned to disclose more critical information (M = 2.86, SD = 0.27) than unlawful act participants (M = 2.55, SD = 0.40, F(1, 124) = 28.17, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.19). The finding demonstrated a large effect based on the benchmark values (ηp2 = 0.01 small; ηp2 = 0.06 medium; ηp2 = 0.14 large) provided by Cohen (1988) and was in line with hypothesis 3a.

Participants in the suspicion condition (M = 2.77, SD = 0.35) planned to disclose more critical information than participants in the no suspicion condition (M = 2.64, SD = 0.39, F(1, 124) = 4.20, p = 0.043, ηp2 = 0.03) with a small effect. This finding was in line with hypothesis 3b.

No significant interaction effect was found between Act and Presence of Suspicion (F(1, 124) = 2.65, p = 0.11, ηp2 = 0.02). A closer look at the data revealed rather low standard deviations for the first four items that were included in the disclosure scale (items 1–4) (SD range = 0.33–0.56). Specifically, the vast majority of the participants replied for items 1–4 that they intend to disclose each specific piece of critical information voluntarily (between 74.2 and 87.5%). For item 5 (whether or not participants would disclose their true intentions at the store), this number dropped to 55.5% (SD = 0.86). Due to the lack of variance in items 1–4, we decided–as an exploratory step–to calculate another two-way ANOVA and only included item 5 (“Do you plan to disclose your true/honest intentions in the department store “XXX”?”). Results showed again–in line with hypotheses 3a and 3b–significant main effects for the Act condition (F(1, 124) = 99.60, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.45) with a large effect and for the Presence of Suspicion condition (F(1, 124) = 10.45, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.08) with a medium effect. Beyond that, results showed a small but significant interaction effect (F(1, 124) = 4.45, p = 0.037, ηp2 = 0.04). Simple-effects analyses revealed that when suspicion was directed at unlawful act participants (i.e., questioning them as suspects) they were significantly more willing to disclose their true intentions (M = 2.03, SD = 0.86) than when they were not under suspicion (i.e., questioned as witnesses) (M = 1.44, SD = 0.72, F(1, 124) = 14.27, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10) with a moderate effect size. For lawful act participants, no significant difference occurred between the suspicion (M = 2.91, SD = 0.30) and the no suspicion condition (M = 2.78, SD = 0.49, F(1, 124) = 0.63, p = 0.43, ηp2 = 0.005). Hence, only for the item on participants’ willingness to disclose information about their true intention at the store (but not for the whole disclosure scale), we found support for hypothesis 3c.

Discussion

The current study adds to the limited pool of studies examining the strategies of people who are innocent of the crime under investigation but have executed a different unlawful act (unlawful act participants). Specifically, it examined the effect of suspicion, either present or absent, on participants’ (a) planned counter-interrogation strategies and (b) willingness to disclose critical information.

First, the current study examined which strategies participants reported and whether the extracted strategies differed between the four experimental conditions. Differences between unlawful and lawful act participants occurred only for strategies that could clearly be labeled “forthcoming” or “evasive.” In line with hypothesis 1a and previous research (Clemens and Grolig 2019; Colwell et al. 2018), it was found that unlawful act participants reported forthcoming strategies (in the current study these were: to be honest, to give a detailed statement, and to suggest ideas to the interviewer of how to prove their innocence) significantly less often than lawful act participants. In line with hypothesis 1b and in line with previous research, the evasive strategy to be deceptive was reported significantly more often by unlawful than lawful act participants (Clemens and Grolig 2019; Colwell et al. 2018). For the self-presentation strategy to make a good and truthful impression, we found–contrary to our hypothesis–no significant difference between lawful and unlawful act participants. However, this finding is in line with research showing no difference between innocent and guilty mock suspects when it comes to their impression management (i.e., the purposeful control of nonverbal and demeanor cues) (e.g., Hartwig et al. 2010; Vrij et al. 2010).

Hypothesis 2 was only partially supported, as merely for one of the eight extracted categories of strategies a significant difference occurred. Specifically, it was shown that participants in the suspicion condition reported the strategy to request information about the investigation significantly more often than participants in the no suspicion condition. Although this strategy was previously unlabeled (possibly serving multiple purposes), in the current context, it can be interpreted as a proactive strategy. Thus, we reason that the use of this strategy mirrors a mindset of participants in the suspicion condition (i.e., questioned as potential suspects) to proactively control and manage the situation by being informed about the existing facts. Consequently, the data indicate that participants under suspicion (when innocent of the crime under investigation) choose significantly more often a proactive approach than participants under no suspicion. This might be due to the feeling that it is their responsibility to fully understand and consequently impact the situation (Granhag et al. 2009). In the current study, the participants were naïve within the legal system, which might be one of the reasons for their proactiveness. Participants who are experienced with the legal system might apply a different approach (possibly more reactive) (Granhag et al. 2009).

Furthermore, the explorative findings indicate that being under suspicion does not significantly affect lawful and unlawful suspects’ choice of strategies to be honest and to be deceptive. Specifically, regardless of whether being under suspicion or not, more of the lawful (vs. unlawful) act participants still reported that they plan to be honest and more of the unlawful (vs. lawful) act participants reported that they plan to lie (avoid and/or deny) to a certain extent. Interestingly, when suspicion (vs. no suspicion) was directed towards unlawful act participants, they reported the strategy to be deceptive less frequently. This difference did, however, not reach the level of significance.

The current study showed–as expected–that unlawful act participants were less willing to disclose critical information than lawful act participants. This finding was in line with hypothesis 3a and with previous research on different information management approaches in completely innocent (i.e., lawful act participants), partially innocent (i.e., unlawful act participants) and guilty interviewees (e.g., Clemens and Grolig 2019; Colwell et al. 2018; Granhag and Strömwall 2002; Strömwall et al. 2006).

Beyond that, we found support for hypothesis 3b which predicted that participants in the suspicion condition would disclose more critical information than participants in the no suspicion condition. This finding corresponds with the existing research on naïve guilty suspects’ willingness to share information under high and low suspicion (Granhag et al. 2009). Beyond that, the current study adds knowledge to the previous findings of Granhag and colleagues by showing that the apparent responsibility guilty naïve participants felt to actively convince the interviewer of their innocence (via increased disclosure of potentially incriminating information) also seems to apply to innocent naïve participants. When facing a potentially endangering situation in which one is confronted with suspicion (although this suspicion is unjustified), the naïve participants in the current study also seemed to have felt an increased need to open up, display their honesty, and share (even critical) information compared to the more secure no suspicion situation.

Beyond that, we did not find support for hypothesis 3c in general. As an exploratory step, we analyzed item 5 (disclosure of true intentions at the store) separately. The results showed that unlawful (but not lawful) act participants were significantly more willing to disclose their true intentions in the suspicion (vs. no suspicion) condition. We believe that the non-significant overall result is due to a lack of variance for items 1–4 as most of the participants reported that they intend to disclose this information voluntarily. This finding can be explained by the fact that items 1–4 describe actions that, though being potentially incriminating (as they put the participants at the crime scene), are not considered to be a major threat to the participants (being in the department store where the crime occurred; being in the book section of the department store where the crime occurred; seeing the grey backpack from which the money was stolen; touching the grey backpack from which the money was stolen). As none of the participants committed the crime under investigation (i.e., none of them is guilty), admitting the previously mentioned actions is expected to be easier for them than it would be for guilty participants. The actual unlawful act (buying a dubious mobile phone) is most closely connected to item 5 (disclosure of true intentions at the store). Consequently, honestly sharing information on this item (vs. the first four items) is expected to be the biggest challenge to the unlawful act participants. In addition, it is rather easy to deny one’s true intentions at a place. Thus, some unlawful act participants were not willing to openly share the critical information on their true intentions (vs. the information requested in items 1–4), which led to an increased variance in the data for item 5 and the reported results above.

The finding that unlawful act participants were significantly more willing to disclose their true intentions in the suspicion condition than in the no suspicion condition is new to the literature. An explanation can be found in the work of Darley and Fazio (1980) who argue that people sometimes try to dispel the impression of their communication partner. This attempt however depends on two factors: (1) the importance of the communication partner to the person and (2) the belief of the person about the validity of the communication partner’s impression. Thus, when the communication partner’s impression is important to a person and the person considers this impression to be incorrect, s/he will likely try to eliminate this impression. In contrast, if the impression of the communication partner seems accurate to a person, s/he will likely behave in a manner that strengthens this impression. Transferred to the current study, an unlawful act participant, who is informed about the police considering him/her to have committed the crime under investigation (the theft), will likely disagree with this suspicion and will therefore try to fight it by emphasizing that s/he has nothing to hide and is, in fact, innocent of that crime (i.e., s/he will be honest and share all/most of the critical information). In contrast, an unlawful act participant, who is informed by the police that s/he will be questioned as a witness (i.e., no suspicion condition), will aim to maintain this impression and will rather refrain from providing information that might make him/her appear in a bad light and potentially suspicious.

Next, we want to take a closer look at lawful act participants, who were mostly unaffected by the different suspicion conditions, which led to a non-significant difference. This result is in line with recent findings by Portnoy et al. (2019). An explanation for this finding could be the fact that lawful act participants’ main approach continuously was to be honest and open. Almost all of them reported that they were willing to voluntarily share the information about their actions/intentions at the department store even when no suspicion was directed towards them. For lawful act participants in the suspicion condition, to show an even higher willingness to share information was almost impossible. This ceiling effect could have caused the non-significant finding. The distinct tendency of lawful act participants to tell the truth is also in accordance with the findings of Elaad (2019). In his study, police investigators and laypeople were asked to imagine that, although being innocent of the offense, they are interrogated by police investigators as suspects. The participants could choose between telling an implausible truth or a (more) plausible lie. Laypeople showed a preference for implausible truths over (more) plausible lies, although this could put them at risk of not being believed (as implausibility is a cue to deception and a predictor of deception judgments, e.g., DePaulo et al. 2003; Hartwig and Bond 2011).

The previously discussed findings have relevant practical implications. The current study replicated and expanded the findings of Clemens and Grolig (2019) by showing that unlawful act suspects sometimes use evasive strategies (i.e., deception) during an investigation, both when they are questioned as witnesses and suspects. This might potentially put them at the risk of being wrongfully assessed as guilty. Furthermore, the findings point in the direction that suspicion (even when unjustified) does not need to be a direct threat to innocent participants. Specifically, lawful act participants’ high willingness to openly share critical information on their intentions in the store remained present in both suspicion conditions. Unlawful act participants, on the contrary, reported a higher willingness to share critical information on their intentions in the store (i.e., to be more open and honest) when being under suspicion (vs. no suspicion). Thus, suspicion rather restrained unlawful act participants from being deceptive. However, one needs to keep in mind that the reasoning above only holds if the interviewee (completely innocent or innocent with an unlawful secondary act) is not questioned with a manipulative/unethical/accusatory interrogation method, pressured into a confession and if the secondary act is less severe than the crime under investigation.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has four different limitations. The first limitation is the fact that the sample consisted of people from the general population with no criminal experience (university students, employees, etc.), which raises questions about the extent to which our findings can be generalized to real-life settings. In their study on guilty suspects (i.e., participants were guilty of an imagined mock-crime under investigation and were suspected of it), Granhag et al. (2009) showed that people with criminal experience (vs. no criminal experience) were more prone to withhold and deny potentially incriminating information. Whether this more defensive and skeptical mindset also applies to experienced innocent participants (i.e., lawful and unlawful act participants) needs to be examined in the future. Thus, a replication of the current study should be conducted using a forensically more relevant sample (e.g., former criminals, prison inmates).

Second, the current study was an imaginary mock-crime study. We made an aware decision to apply this experimental approach as it is far more economical with research resources than more traditional role-play mock-crime studies in which participants factually execute their actions. One can argue that participants not executing–but merely imagining–their actions might cause them to not internalize their role-play character and consequently not (re)act according to the role that they are asked to take part in. To minimize this possible shortcoming of the design, we made efforts to ensure that the participants were able to internalize the actions they were asked to imagine (by using both a written and an auditive format). In addition, we controlled for whether participants were (a) sufficiently motivated to participate and (b) sufficiently able to put themselves into the role they were asked to imagine. Results showed rather high ratings for both variables. Consequently, it can be assumed that participants’ motivation and ability to internalize their actions were sufficient in the current study. However, future research should consider replicating the current study with participants physically taking part in an actual mock-crime role-play.

Third, the current study assessed the intended instead of the actual behavior. This was because the study did not include a mock interrogation in which the participants could have displayed any behavior. It is reasonable to assume that the reported intended behavior may not be fully congruent with the behavior that is eventually applied, specifically as the participants of the current study (most likely) never were confronted with a situation similar to the one used in this imaginary mock-crime study, which could have helped them to estimate their behavior. However, research suggests that intentions in general can predict a person’s behavior considerably accurate in situations in which a person can control his/her behavior (e.g., Ajzen 1991). Nevertheless, future research would profit from assessing actual behavior.

Fourth, the method of self-reports to assess participants’ intended counter-interrogation strategies is a further potential limitation. Although we are aware of the fact that reported behavior can differ from applied behavior (e.g., Ajzen et al. 2004), Granhag et al. (2013) obtained similar results for participants’ self-report measures (subjective measures) and participants’ actual interview performance (objective measures). In addition, using participants’ self-reports is a commonly used method to examine their counter-interrogation strategies with satisfactory results (e.g., Clemens et al. 2013; Clemens and Grolig 2019; Strömwall and Willén 2011). However, future studies should consider other methods than self-reports to investigate counter-interrogation strategies.

Conclusions

The present study addressed (a) the counter-interrogation strategies and (b) the willingness to disclose critical information of people who are innocent of the crime under investigation but who were at the crime scene to either commit a lawful or an unlawful act and who were subsequently called for a witness interview (i.e., no suspicion) or a suspect interview (i.e., suspicion). The overall findings indicate that the main strategy for both lawful and unlawful act participants was to be honest. However, although innocent of the crime under investigation, some unlawful act participants reported to be deceptive as an intended strategy.

While most of the planned counter-interrogation strategies participants reported were not significantly affected by the presence or absence of suspicion in the current study, suspicion seems to push interviewees, in general, to take a more proactive approach (e.g., to request for information about the investigation) during an interview. Beyond that, unlawful act participants’ willingness to disclose critical information (about their true intentions at the crime scene) was higher when suspicion (vs. no suspicion) was directed towards them. This increased forthcomingness is likely due to an effort by the interviewees to make a truthful impression on the interviewer and to proactively convince him/her of their innocence. In turn, when being informed that the police would interview them as a witness, unlawful act participants refrained to a higher extent from sharing the truth about their true intentions at the crime scene. This leads to more deception (withholding and/or denial of critical information) and will consequently increase the inconsistency of unlawful act participants’ statements with potential information the police hold, which could cause them to be wrongfully assessed as guilty of the crime under investigation.

Availability of Data and Material

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study can be found at https://osf.io/26tfh/. All other materials (e.g., instructions, questionnaire items) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Students.

Former criminals, who had lied to the police before.

When we refer to subjects under suspicion (i.e., suspects) and subjects under no suspicion (i.e., witnesses) combined, we use the general term “participants”.

The minimum sample size of 128 was determined by using the G*Power software (Cohens’s f effect size = 0.25, alpha = 0.05, and power = 0.80) (Faul et al. 2007).

This procedure was chosen to increase the vividness of the story and participants’ ability to imagine themselves executing the actions mentioned in the story.

Participants were also asked to explain the purpose/expected effect for each of the reported strategies. This information was however unrelated to the predictions in the current study and thus, is not analyzed and reported in the current manuscript.

“Do you plan to disclose in the upcoming interview that you were in the department store “XXX” on Monday the 8th of April?” (1), “Do you plan to disclose in the upcoming interview that you were in the book section of the department store “XXX” on Monday the 8th of April?” (2), “Do you plan to disclose in the upcoming interview that you saw the grey backpack?” (3), “Do you plan to disclose in the upcoming interview that you touched the grey backpack?” (4), “Do you plan to disclose your true/honest intentions in the department store “XXX”?” (5).

Lawful act/no suspicion vs. lawful act/suspicion vs. unlawful act/no suspicion vs. unlawful act/suspicion.

Lawful act/no suspicion vs. lawful act/suspicion; unlawful act/no suspicion vs. unlawful act/suspicion; lawful act/no suspicion vs. unlawful act/no suspicion; lawful act/suspicion vs. unlawful act/suspicion.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen I, Brown TC, Carvajal F (2004) Explaining the discrepancy between intentions and actions: the case of hypothetical bias in contingent valuation. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 30(9):1108–1121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204264079

Baumeister RF (1982) A self-presentational view of social phenomena. Psychol Bull 91(1):3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.1.3

Burgoon JK, Buller DB, White CH, Afifi W, Buslig ALS (1999) The role of conversational involvement in deceptive interpersonal interactions. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 25(6):669–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025006003

Clemens F (2013) Detecting lies about past and future actions: the strategic use of evidence (SUE) technique and suspects’ strategies. (Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Psychology, University of Gothenburg). Retrieved from https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/32705/1/gupea_2077_32705_1.pdf

Clemens F, Granhag PA, Strömwall LA (2013) Counter-interrogation strategies when anticipating questions on intentions. J Invest Psychol Offend Prof 10(1):125–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1387

Clemens F, Grolig T (2019) Innocent of the crime under investigation: suspects’ counter-interrogation strategies and statement-evidence inconsistency in strategic vs. non-strategic interviews. Psychol Crime Law 25(10),945–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2019.1597093

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

Cohen J (1992) A power primer. Psychol Bull 112(1):155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Colwell K, Memon A, James-Kangal N, Martin M, Wirsing E, Cole LM, Cooper B (2018) Innocent suspects lying by omission. J Foren Psychol 3(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2475-319X.1000133

Darley JM, Fazio R (1980) Expectancy confirmation processes arising in the social interaction sequence. Am Psychol 35(10):867–881. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.35.10.867

DePaulo BM, Lindsay JJ, Malone BE, Muhlenbruck L, Charlton K, Cooper H (2003) Cues to deception. Psychol Bull 129(1):74–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.74

Elaad E (2019) Plausible lies and implausible truths: police investigators’ preferences while portraying the role of innocent suspects. Leg Criminol Psychol 24(2):229–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12155

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39:175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Granhag PA, Clemens F, Strömwall LA (2009) The usual and the unusual suspects: level of suspicion and counter-interrogation tactics. J Invest Psychol Offend Prof 6(2):129–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.101

Granhag PA, Hartwig M (2008) A new theoretical perspective on deception detection: On the psychology of instrumental mind-reading. Psychology, Crime & Law 14(3):189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160701645181

Granhag PA, Hartwig M, Mac Giolla E, Clemens F (2015) Suspects’ verbal counter-interrogation strategies: towards an integrative model. In P.A. Granhag, A. Vrij, & B. Verschuere (Eds). Deception detection: current challenges and cognitive approaches (pp. 293–314). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118510001.ch13

Granhag PA, Mac Giolla E, Strömwall LA, Rangmar J (2013) Counter-interrogation strategies among small cells of suspects. Psychiatry, Psychology & Law 20(5):705–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2012.729021

Granhag PA, Strömwall LA (2002) Repeated interrogations: verbal and non-verbal cues to deception. Appl Cogn Psychol 16(3):243–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.784

Hartwig M, Bond CF (2011) Why do lie-catchers fail?. A lens model meta-analysis of human lie judgments. Psychol Bull 137(4):643–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023589

Hartwig M, Granhag PA, Strömwall LA (2007) Guilty and innocent suspects’ strategies during police interrogations. Psychology, Crime & Law 13(2):213–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160600750264

Hartwig M, Granhag PA, Strömwall LA, Doering N (2010) Impression and information management: on the strategic self-regulation of innocent and guilty suspects. Open Criminol J 3:10–16. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874917801003010010

Hill C, Memon A, McGeorge P (2008) The role of confirmation bias in suspect interviews: a systematic evaluation. Leg Criminol Psychol 13(2):357–371. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532507X238682

Hines A, Colwell K, Hiscock-Anisman C, Garrett E, Ansarra R, Montalvo L (2010) Impression management strategies of deceivers and honest reporters in an investigative interview. The Eu J Psychol Appl Legal Cont 2(1):73–90

Kassin SM, Goldstein CC, Savitsky K (2003) Behavioral confirmation in the interrogation room: on the dangers of presuming guilt. Law Hum Behav 27(2):187–203. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022599230598

Kassin SM, Norwick RJ (2004) Why people waive their Miranda rights: the power of innocence. Law Hum Behav 28(2):211–221. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:LAHU.0000022323.74584.f5

Landis J, Koch G (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

Leiner DJ (2016) SoSci Survey (Version 2.6.00) Computer software. Available at https://www.soscisurvey.de

Lerner MJ (1980) The belief in a just world. Plenum, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5_2

Portnoy S, Hope L, Vrij A, Granhag PA, Ask K, Eddy C, Landström S (2019) “I think you did it!”: examining the effect of presuming guilt on the verbal output of innocent suspects during brief interviews. J Invest Psychol Offend Prof 16(3):236–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1534

Savitsky K, Gilovich T (2003) The illusion of transparency and the alleviation of speech anxiety. J Exp Soc Psychol 39(6):618–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-1031(03)00056-8

Strömwall LA, Hartwig M, Granhag PA (2006) To act truthfully: nonverbal behaviour and strategies during a police interrogation. Psychology, Crime & Law 12(2):207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160512331331328

Strömwall LA, Willén RM (2011) Inside criminal minds: offenders’ strategies when lying. J Invest Psychol Offend Prof 8(3):271–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.148

Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, Ciarocco NJ (2005) Self-regulation and self-presentation: regulatory resource depletion impairs impression management and effortful self-presentation depletes regulatory resources. J Pers Soc Psychol 88(4):632–657. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.632

Vrij A, Mann S, Leal S, Granhag PA (2010) Getting into the minds of pairs of liars and truth tellers: an examination of their strategies. Open Criminol J 3:17–22. https://doi.org/10.2174/18749178010030200017

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tessa Beyer, Kristina Siewert, and Marleen Zabeil for their help with the collection of data.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Central gender equality budget by the board of Kiel University, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Franziska Clemens. Data collection: Franziska Clemens (with the help of the named student assistants). Analysis and interpretation of results: Franziska Clemens and Tuule Grolig. Draft manuscript preparation: Franziska Clemens and Tuule Grolig. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine (Kiel University).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for the publication of the anonymized data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Clemens, F., Grolig, T. What Will You Do When They Think It Was You? Counter-interrogation Strategies of Innocent Interviewees Under Suspicion vs. No Suspicion. J Police Crim Psych 38, 381–394 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-022-09525-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-022-09525-7