Abstract

Purpose of Review

A modified Delphi process was undertaken to provide a US expert-led consensus to guide clinical action on short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) use. This comprised an online survey (Phase 1), forum discussion and statement development (Phase 2), and statement adjudication (Phase 3).

Recent Findings

In Phase 1 (n = 100 clinicians), 12% routinely provided patients with ≥4 SABA prescriptions/year, 73% solicited SABA use frequency at every patient visit, and 21% did not consult asthma guidelines/expert reports. Phase 3 experts (n = 8) reached consensus (median Likert score, interquartile range) that use of ≥3 SABA canisters/year is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and asthma-related death (5, 4.75–5); SABA use history should be solicited at every patient visit (5, 4.75–5); usage patterns over time, not absolute thresholds, should guide response to SABA overuse (5, 4.5–5).

Summary

Future asthma guidelines should include clear recommendations regarding SABA usage, using expert-led thresholds for action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Asthma affects 25.3 million people in the USA, and 60% of adults and 44% of children have uncontrolled asthma as defined by the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) [1].

Overuse of short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs) for as-needed symptom relief has repeatedly been found to be common in uncontrolled asthma [2,3,4, 5••, 6, 7, 8••, 9], though the definition of “overuse” varies across studies [2, 4]. High SABA use is associated with exacerbations, asthma-related hospitalizations, and increased risk of asthma-related death [5••, 6, 10••, 11,12,13]. Progressively increasing SABA use has been observed from 10 to 14 days before an exacerbation [14]; thus, identifying and acting upon such periods may halt exacerbation progression and improve outcomes [6, 15].

Understanding and monitoring SABA use is a cornerstone of asthma management; however, managing SABA use is challenging [11, 16,17,18,19,20,21]. Although asthma guidelines acknowledge the problem of SABA overuse, define it in broad terms, and advise intervention if it occurs, patients and healthcare systems would stand to benefit from more detailed recommendations for monitoring and next steps. Established methods of monitoring SABA overuse (patient recall and/or prescription refill data) are often subjective or inaccurate [22•]. Furthermore, SABA overprescription, defined as >2 canisters/year [6] or ≥3 canisters/year [8••, 23, 24•], remains prevalent across all asthma severities, and asthma guidelines offer differing advice for SABA prescribing [11, 18,19,20,21]. Reliever medications, including SABA, are also available without a prescription in several countries [3, 10••]—potentially including the USA in the future [25]—hindering effective monitoring of overuse. To address these issues, critical exploration of SABA use in asthma is needed.

The modified Delphi method is a well-established approach to answer a research question through expert input to identify a consensus view [26]. Panels typically have 7–15 members to balance diverse representation with the opportunity for intimate group discussion [26]. The method is a systematic and iterative process allowing for reflection, consideration of nuance, and reconsideration of personal opinions in response to those of other experts [27]. This approach is used when current knowledge is incomplete or potentially subjective or when obtaining further evidence is not feasible [28, 29].

The aim of this study was to provide expert-led guidance on appropriate clinical action in response to high SABA use and/or changes in patients’ SABA usage patterns, using a modified Delphi mixed-method process to reach a consensus among a panel of experts in respiratory medicine and asthma management.

Methods

Study Design

In 2021, a multiphase, iterative, modified Delphi mixed-method consensus-building process was conducted. The Delphi method has limitations such as lack of standardized consensus-defining methods, problems associated with anonymity, and potential lack of generalizability beyond the experts included [30]. It has therefore been adapted in several ways to fit specific research needs. This study used a mixed-method approach, including an iterative set of interactions with clinicians treating asthma, to gain insight into SABA reliever medication use among patients with asthma.

The project team met twice weekly for approximately 3 months to plan the strategic approach to this research. As part of this planning phase, a targeted review of existing literature on SABA reliever medication use was conducted. Searches in PubMed and Google Scholar, conducted in September 2021, included combinations of the following search terms: asthma, short-acting beta antagonist, SABA, rescue inhaler, rescue medication, albuterol, use, overuse, abuse, burst, and treatment patterns. Through team discussion and input from the panel Chair, key themes were extracted from the literature findings and used to inform the development of study domains. These would serve as a framework for ensuring all aspects of SABA use were addressed in the subsequent study design and development of study-related materials. As a result of the extensive literature search, a total of 14 SABA use domains were identified: overuse (volume/amount/quantity/frequency), appropriate use, reducing risk, exacerbations, practice guideline alignment, objective testing (of disease severity), socioeconomics, efficacy, safety, disease severity/burden, relationship between maintenance and reliever therapy, SABA canister dispensing control and monitoring to prevent overuse, healthcare resource utilization (HRU), and shared decision-making.

The three-phase study comprised (1) an anonymous online survey exploring SABA asthma reliever beliefs and real-world practice, (2) an anonymous forum discussion with comprehensive evidence review and SABA statement development, and (3) an expert-guided formal modified Delphi adjudication of generated statements (Fig. 1; Appendix 1).

Key study objectives were to gather clinician insights on asthma reliever medication use in real-world practice, gain an understanding of practice-based clinical decision-making related to asthma reliever medications (including SABA), identify educational needs to support healthcare professional’s (HCP) confidence in using objective inhaler use data for clinical management, and develop consensus statements.

Participants

Eligible Phase 1 participants, recruited through a third-party clinician panel, had 2 to 30 years of clinical experience, were currently treating patients with asthma in the USA (excluding Vermont and Maine as HCPs cannot participate in paid forums), and were primary care physicians (PCPs) or specialists (allergists, pulmonologists). Phase 2 panelists were nationally known asthma clinical specialists (identified by Sensified, LLC through a search of professional societies, published literature, and treatment guidelines) currently managing patients with asthma in the US and actively researching asthma and SABA use. Phase 3 panelists were a subset of Phase 2 participants and were independently chosen by Sensified, LLC to continue to Phase 3 based on their contribution to the field.

Results

Phase 1

One hundred clinicians from 48 states plus Washington, D.C., completed the survey. These clinicians comprised 50 PCPs (38 family medicine, 10 adult primary care, 2 pediatric primary care) and 50 specialists (35 allergists, 15 pulmonologists), averaging 21.3 years in practice. Mean number of patients seen was 63/week. Full survey results are listed in Appendix 5.

For SABA prescriptions and refills, 76% PCPs provided 1–3 SABA refills to patients per prescription versus 66% of allergists and 100% of pulmonologists, and 20% of PCPs and 6% of allergists provided ≥4 SABA refills per prescription. Overall, 21% of Phase 1 study participants reported that their practice provided >1 SABA canister/prescription over half of the time.

Several questions addressed SABA use frequency and asthma control. When asked the lowest number of SABA episodes/week likely to be representing an impending or ongoing asthma exacerbation, 24% (PCPs), 34% (allergists), and 13% (pulmonologists) said ≥3 SABA episodes/week. Additionally, 18%, 31%, and 33%, respectively, deemed that ≥5 SABA episodes/week likely represent an impending or ongoing asthma exacerbation. Reasons for exceeding a SABA use level that clinicians considered appropriate could represent impending or ongoing exacerbations (80% of clinicians); a loss of asthma control (79%); inappropriate use (66%); an impending urgent, emergent, or hospital visit for asthma (63%); or inhaler technique challenges (61%). When clinicians were asked to specify which of these scenarios were most often represented in their practice when a patient exceeded the appropriate level of SABA use, the responses were a loss of asthma control (53% of clinicians), an impending or ongoing exacerbation (29%), an impending urgent, emergent, or hospital visit for asthma (11%), inappropriate use (6%), and inhaler technique challenges (1%).

Regarding how often clinicians seek information on SABA use history: 73% of overall participants (56% PCPs, 91% allergists, 87% pulmonologists) indicated at every visit; 22% (34% PCPs, 9% allergists, 13% pulmonologists) indicated at most visits; and 5% (10% of PCPs only) indicated occasionally, depending on factors for the visit.

Clinicians were asked what clinical actions they implement when SABA overuse was identified. Most participants (76%) overall thought that a medication change should be considered. Other responses included inhaler technique training or additional information gathering (60% of clinicians), an asthma education refresher (56%), or a specialty referral (22%).

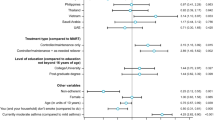

Regarding use of asthma control evaluations, 40% of all clinicians (56% PCPs, 17% allergists, 40% pulmonologists) did not use any validated asthma control survey (e.g., Asthma Control Test [31], Asthma Control Questionnaire) for assessing patients with asthma. Figure 2 shows which asthma guidelines and expert reports were used for SABA use guidance. The National Institutes of Health (NIH/NAEPP) guideline was used by 36% of clinicians (26% PCPs, 54% allergists, 27% pulmonologists). Overall, 23% of clinicians (10% PCPs, 26% allergists, 60% pulmonologists) followed Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) recommendations. Other guidelines included European Respiratory Society (2% of all clinicians), American Thoracic Society (11%), and Baylor University Rules of Two® (6%). However, 21% of clinicians (42% PCPs) did not use any SABA medication guidance.

Responses to the Phase 1 survey question “In your asthma management practice, which (if any) of the following asthma guideline/expert report recommendations do you routinely use for SABA rescue medication guidance?” 100 US clinicians completed the Phase 1 survey. Participants were required to select the option they most frequently used. ATS, American Thoracic Society; ERS, European Respiratory Society; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; NIH/NAEPP, National Institutes of Health/National Asthma Education and Prevention Program

Of all Phase 1 study participants, 80% agreed or strongly agreed that the asthma guidelines or expert reports they use provide clear recommendations regarding effective and safe amounts of SABA reliever. Moreover, guidelines were perceived to provide clear recommendations on when to take clinical action for SABA overuse (81% agreed or strongly agreed) and what specific action to take (83% agreed or strongly agreed). However, experts in Phase 3 (see below) did not agree with these perceptions.

Phase 2

The pre-meeting survey (Appendix 2) was completed by 10/15 expert panelists. Most panelists (80%) deemed exceeding an appropriate SABA use to be associated with high or very high risk for negative outcomes. At least 90% said healthcare costs, HRU, and quality of life would be improved if exacerbations associated with SABA use could be lessened in severity or prevented. In contrast to the Phase 1 study participants, 60% of expert panelists said that literature, expert reports, and/or guidelines did not provide clear recommendations for effective and safe thresholds of SABA medication use. Furthermore, 70% of expert panelists noted that no clear recommendations were provided on what clinical action to take, and when, in response to high SABA use.

All 15 panelists participated in the online forum discussion. Panelists provided thoughts on five patient cases and their likely response. Panelist responses largely referenced concern about potential exacerbations or loss of disease control and a desire for more patient-specific information. The most common clinical actions that might be taken by the group for a patient reaching the threshold for appropriate SABA use included: adjustment of therapy (increase or addition of therapies [73% of panelists], oral corticosteroid [40%]), consideration of triggers (53%), further evaluation (47%), and adherence assessment (40%).

Phase 3

Overall, 97 statements were compiled from Phases 1 and 2 encompassing nine topics: gathering information on disease and SABA use, patient SABA use history, SABA prescribing, SABA use levels, exacerbations, disease control, clinical actions and SABA use levels, socioeconomics and SABA use, and guidelines. In the pre-meeting poll, eight participants (five allergists, two pulmonologists, one nurse scientist) scored these statements; 61 were accepted, 6 were rejected, and 30 required revisions that were discussed in the video conference. Through the video conference and post-meeting poll, 23 modified statements were scored and of these 9 were accepted and 14 rejected. Thus, the expert panel consensus consisted of 70 accepted statements relating to eight topics (Table 1); the topic “guidelines” did not gain consensus.

Several consensus points were noteworthy. Use of ≥3 SABA canisters/year was associated with increased risk of exacerbation and asthma-related death. Patients should have SABA refills, with close monitoring of refill rates. Moreover, ≥5 SABA episodes/week and/or SABA episodes ≥50% and >100% above the patient’s baseline were considered to represent an impending or ongoing asthma exacerbation. History of SABA usage should be solicited at every patient encounter. Reliability of usage frequency should be considered since patient-sourced information may be inaccurate and pharmacy refill data may not correlate with actual use. Consideration should be given to employing digital health tools to assess SABA use. Individual SABA use data (e.g., increase from baseline, usage patterns over time) should guide clinical actions, rather than absolute thresholds.

Discussion

We undertook a modified Delphi mixed-method consensus-building process, to gain clinician insights on real-world clinical decision-making around SABA use in asthma, with the objective of providing guidance on identification of SABA overuse and appropriate clinical action. US clinicians reported their opinions and experiences concerning real-world SABA use in asthma. Subsequently, a two-step process involving key experts produced 70 consensus statements providing valuable insight into asthma management in the USA relating to SABA use. Importantly, asthma specialists and PCPs participated in this study, thereby ensuring that multiple clinical practice settings treating a variety of patient types were represented.

The Scale of the Challenge: Defining SABA Overuse and Its Link to Poor Outcomes

It is by now well established that SABA overuse is widespread and is linked to poor asthma outcomes [10••, 12, 32•]. The SABINA study investigators reported that the greater the number of SABA canisters prescribed per year, the greater the odds of patients having uncontrolled asthma [10••].

Several asthma guidelines and expert reports define SABA overuse based on a specified numeric threshold of canisters/year or on rates of usage. GINA state that refill rates of ≥3 SABA canisters/year are associated with an increased risk of severe exacerbations, and rates of ≥12 canisters/year are associated with substantially increased risk of death [11]. They advise that SABA overuse necessitates intervention to improve overall control [11]. Baylor University Rules of Two® guidance states that using SABA for ≥2 days/week or for ≥2 episodes/week signals uncontrolled asthma [16, 19], and NIH/NAEPP guidelines comment that using >1 SABA canister for as-needed symptom relief during 1 month (potentially ≥12 canisters/year) indicates SABA overuse [21].

Phase 1 participants and Phase 3 experts had differing opinions on asthma guidelines’ clarity on SABA use. In Phase 1, the NIH/NAEPP guidelines were the most commonly followed overall and the guidelines of choice for allergists, whereas most pulmonologists preferred GINA recommendations. However, many PCPs surveyed did not consult asthma guidelines or expert reports for SABA guidance. Thus, it is not surprising that adherence to asthma guidelines is often poor, particularly in the primary care setting [33•, 34, 35••].

Consistent with the guidelines, however, our experts agreed that use of ≥3 SABA canisters/year was associated with an increased risk of exacerbations and asthma-related death and recommended that refill rates be monitored closely. In the real world, these thresholds are routinely exceeded. In the multinational SABINA III study, 38% of patients were prescribed ≥3 canisters/year, and some were prescribed ≥13 canisters/year [10••]. To et al. reported that in Canada, 5.3% of patients with asthma (≥65 years) were prescribed ≥6 SABA canisters/year [12]. Worth et al. reported that in Germany, 36 to 38% of patients with asthma were prescribed ≥3 canisters/year, with overuse increasing with increasing asthma severity [32•]. One-fifth of the PCPs in our Phase 1 reported routinely providing ≥4 SABA refills in a year. It was noted in Phase 3 of our study that changing practice around SABA prescribing will be important in addressing the problem of overuse, and a key goal will be the provision of additional guidance around the recommended number of SABA refills.

Since a change to the GINA guidelines in 2019, SABA monotherapy is no longer recommended [11, 36]. Instead, to reduce the risk of serious exacerbation, adults and adolescents with moderate to severe asthma should receive daily inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)-containing treatment. Evidence shows, however, that real-world adherence with ICS is poor [37] and most patients are still receiving SABA monotherapy [38].

Perception Versus Reality: Self-Reported SABA Use and Asthma Control

The rate of SABA use tends to be underestimated by both patients and physicians, and the ready availability of SABA over the counter as well as the possibility of obtaining prescription refills for up to 12 inhalers at a time likely exacerbates the problem. An Australian study of electronic medical records and questionnaires from 720 people with asthma found potential SABA overuse in >50% of patients, yet only 28% self-reported overuse [39•].

Furthermore, many patients are unaware of the risks of SABA overuse. In a real-world cross-sectional observational study in Australian community pharmacies, surveying 375 patients, 23% of SABA overusers (≥3 occasions per week) considered SABAs to be “safe to use,” compared with 8% of non-high SABA users [40•]. Evidence also suggests that high SABA users are less likely to self-report good or excellent health [40•, 41]. Indeed, it was found that a higher proportion (43%) of SABA overusers experienced side effects of dry mouth, palpitations, tremors, chest tightness, muscle cramps, or headache compared with 31% of non-high SABA users [3].

In addition, evidence suggests that patients overestimate the degree of control of their asthma, and both patients and clinicians have low expectations for effective asthma management [42,43,44]. Findings from an online survey of ~2500 people in Asia indicated that, of 2198 patients who perceived their asthma to be controlled, 80% had not in fact achieved GINA-defined asthma control. Furthermore, of the 1225 patients with GINA-defined uncontrolled asthma, only 18% correctly perceived that their asthma is not controlled [45]. Similarly, in a cross-sectional observational study of Australian adults, 11.5% of participants had controlled asthma according to GINA guidelines, but a much larger proportion (66.5%) believed their asthma was well controlled [46].

Together, these observations clearly highlight the present unmet need and the importance of addressing SABA overuse and accurately assessing asthma control.

Getting Personal: Individualizing Asthma Management

Data on SABA use has potential to contribute invaluable insights for risk stratification [47].

GINA indicates that a short-term increase in use of as-needed SABA is associated with increased likelihood of severe exacerbation in the subsequent days or weeks [11]. However, no indicative number of SABA episodes/week likely constituting an impending or ongoing asthma exacerbation is provided. Nor is it made clear how a patient’s baseline level of usage (from which the increase should be observed) should be determined. Clarity on these points is needed to support individualized asthma management.

In Phase 1 of our process, over half of the participants agreed that increased SABA usage indicated loss of asthma control. Our expert consensus reflects current SABA medication guidance and literature suggesting that patients using SABA on ≥2 days/week or for ≥2 SABA episodes/week have inadequately controlled asthma [16, 19]. Importantly, our Delphi consensus indicates that 2 to 3 (and, more strongly, ≥5) SABA episodes/week may be a more appropriate signal for an impending or ongoing exacerbation. It is important to note that the experts concurred that patients who exceeded their normal SABA use by 50 to 100% from their baseline level of usage are at a higher risk of an impending or ongoing exacerbation.

Weekly SABA use thresholds—both absolute and dynamic (changes from baseline behavior)—could help signal a patient’s increased risk of an impending or ongoing exacerbation, which requires prompt medical attention. Inclusion of such thresholds should be considered in future asthma guidelines.

While understanding weekly SABA use is important, SABA use history is also a useful indicator for clinicians to monitor reliever treatment. Most Phase 1 clinicians indicated that they obtain information about prior reliever use at every patient visit; almost all allergists and pulmonologists agreed with collecting SABA history in this way, whereas just over half of PCPs followed this practice. It was noted in Phase 3 that the need for prescription refills can present opportunity for discussions around a patient’s current level of asthma control. Improving guideline adherence in this setting, and so providing patients with access to best-practice management regardless of clinical setting and disease severity, is a key unmet need.

The Unvarnished Truth: Accurately Monitoring SABA Use

A key question naturally arising from recognition of the value of individualized insights on SABA use regards the most effective way to accurately monitor actual use. Phase 3 participants acknowledged that patients need access to SABA, but questioned how this should be monitored. Most asthma guidelines consulted by Phase 1 participants cover general management [11, 16, 18,19,20,21]. While current asthma treatment guidelines emphasize monitoring SABA overuse, most lack detailed guidance on how to do this effectively and do not include specific recommendations for clinical action when a patient has already intensified maintenance therapy [11, 16, 18,19,20,21].

In Phase 1 of our process, patient history/recall was the most common way to assess SABA use (89% of clinicians). However, patient recall is subjective and can be inaccurate [22•]. Indeed, clinicians recognized the need to use other information, as they recognize that patient recall is only generally accurate (28% of clinicians) or is variable (49% of clinicians). Pharmacy refills were the second most common method to monitor SABA use (58% of clinicians), but refill data are inaccurate as they do not capture actual SABA use [48] and also do not lend themselves to acute intervention. Obtaining refill histories can also be difficult and time-consuming, particularly if multiple pharmacies need to be contacted. Moreover, availability of over-the-counter SABAs [3, 10••, 25] could be deleterious as accurate purchasing information would not be available.

The present expert panel favored using digital health tools where possible, as they provide objective, accurate, and reliable reliever usage and maintenance adherence data [22•, 48,49,50, 51•]. Such devices have the potential to support improvements in adherence and asthma control [51•, 52••], though other factors such as poor technique leading to unintentional nonadherence [53] and cost-related underuse [54] may also need to be addressed. In particular, as we aspire achievement of control/remission on therapy [55], the availability of objective insights on SABA use has potential to be of considerable clinical benefit. Phase 3 participants acknowledged the value of information about how SABA is used and its effect on patient’s level of asthma control.

While digital platforms for asthma management may not be needed by all patients (e.g., those with optimally controlled asthma), certain subpopulations with inadequately controlled asthma could benefit from their use; further research is needed to aid in guiding optimal use/patient selection. Asthma guidelines have yet to recommend digital tools in asthma, although this is a likely topic for future GINA updates [11].

Digital health tools would enable collection of SABA usage data at the granularity needed to enable clinicians to manage patients acutely in a more proactive and personalized way. Indeed, a recent study in adults with poorly controlled asthma, treated with an electronic multidose dry powder inhaler with integrated sensors, demonstrated that data collected by the digital inhaler could be used to develop a machine learning model capable of predicting impending exacerbations [56••].

Patients are increasingly embracing digital technology, many now having access to their own health information via apps and smart watches, for example [57]. Furthermore, they are starting to engage with these data and adjusting their own behavior as a result. There may come a time, in the not-too-distant future, where digital technology could be used to alert patients to changes in their asthma or patterns of inhaler use and enable them, and their physicians, to take the most appropriate action.

Knowledge Is Power: Optimizing Clinical Decision-Making

The combination of objective data on patients’ real SABA use and expert guidance, such as that provided by our panel, has potential to substantially enhance clinical decision-making and so reduce exacerbations and improve patient outcomes.

We explored how clinicians currently respond to observed high SABA use. In Phase 1 of our process, the most frequently mentioned actions were medication change (76% of clinicians), inhaler technique training (60%), additional information gathering (60%), and asthma education refreshers (56%), whereas specialty referral was only mentioned by 22% of clinicians. The expert panel agreed that multiple interrelated clinical actions, including inhaler technique training, medication change, additional information gathering via phone or portal (specifically exploring triggers and comorbidities), and an asthma education refresher, should be considered in response to concerning patterns or levels of SABA use. Importantly, the experts emphasized that—while absolute thresholds might be used to identify patients at immediate risk of worsening—clinical asthma management should ideally be based on individual SABA use data (i.e., increase from baseline, usage patterns over time). This necessitates accurate determination of each patient’s typical usage. Information on patients’ day-to-day SABA usage patterns could contribute to more individualized treatment plans. However, this cannot be gleaned simply from claims data stating the number of refills per year. Some patients may have “spikes” of exacerbation-associated SABA use, interspersed between periods of no SABA use. Others with chronically poor asthma control may be consistently overusing SABA on almost a daily basis.

Thus, individual clinical judgment becomes essential, which is more-or-less reliant on the clinician’s experience and confidence in the specific scenario. The quality of objective information available to clinicians also strongly affects their ability to make rational decisions regarding treatment. The 70 consensus statements agreed upon in Phase 3 provide actionable thresholds for asthma clinical practice that could be adopted by clinicians to better monitor SABA usage and prescriptions on a patient-by-patient basis. Figure 3 provides a putative framework for clinical application of these thresholds. Together with more granular data from digital health tools, these consensus statements may support future updates to guidelines or clarify existing opinions around asthma management for SABA use.

Putative framework for clinical application of consensus statements agreed in Phase 3. *ACT/ACQ/patient history are reliant on patient recall and may give inaccurate data. Pharmacy refill data provides a quantitative insight but does not provide information on usage pattern. Digital heath tools can provide an objective real-time dynamic insight into true SABA use. ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire; ACT, Asthma Control Test; HCRU, healthcare resource utilization; ICU, intensive care unit; QoL, quality of life; SABA, short-acting beta2 agonist

Limitations

The Delphi method is widely used in healthcare settings [58, 59] including asthma [60••, 61•]. However, this method has several well-recognized limitations. The present results are qualitative and should be considered as informative guidance only, which requires further objective evidence.

The Delphi process that we undertook was, by design, limited in its scope and sharply focused on SABA usage data and the information that these can provide about a patient’s disease status and treatment needs. Of note, exploration of individual patient factors underlying symptomatic disease was outside of the scope of this process.

Patterns of utilization of multiple inhalers by patients remain poorly understood. Although possessing several SABA inhalers may demonstrate overuse in some patients, others may prefer having several devices to ensure ready access at home, office, car, etc. Such usage should be understood to differentiate problematic versus cautious inhaler ownership.

Conclusions

In this three-phase study, asthma experts recognized the risks of SABA overuse and recommended considering thresholds of SABA use for optimal clinical action based on understanding individual patient asthma clinical profiles. Therefore, gathering patient-specific insights, and improving the validity and reliability of SABA usage data, has the potential to substantially aid asthma management; this target is likely to be better achieved through the utilization of objective measurements of SABA use (e.g., digital inhalers or add-on monitoring devices).

Current guidelines express concerns over SABA overuse and no longer recommend SABA monotherapy. Increased use of digital health tools, enabling day-to-day monitoring and collection of more granular patient-level data, should support the advancement of future asthma guidelines; these could include specific recommendations regarding SABA use patterns, using expert-led thresholds for clinical action such as those described herein. As such, digital inhalers could potentially bridge the gap between guidelines and their implementation and support a more personalized approach to the treatment of asthma.

Data Availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed for the study described in this manuscript are available upon reasonable request. Qualified researchers may request access to patient level data and related study documents including the study protocol and the statistical analysis plan. Patient level data will be de-identified and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of trial participants and to protect commercially confidential information. Please visit www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com to make your request.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most recent national asthma data. 2021. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm.

Amin S, Soliman M, McIvor A, Cave A, Cabrera C. Usage patterns of short-acting β(2)-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids in asthma: a targeted literature review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(8):2556-64.e8.

Azzi EA, Kritikos V, Peters MJ, Price DB, Srour P, Cvetkovski B, et al. Understanding reliever overuse in patients purchasing over-the-counter short-acting beta(2) agonists: an Australian community pharmacy-based survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8): e028995.

Bloom CI, Cabrera C, Arnetorp S, Coulton K, Nan C, van der Valk RJP, et al. Asthma-related health outcomes associated with short-acting β(2)-agonist inhaler use: an observational UK study as part of the SABINA global program. Adv Ther. 2020;37(10):4190–208.

•• Lugogo N, Gilbert I, Tkacz J, Gandhi H, Goshi N, Lanz MJ. Real-world patterns and implications of short-acting β(2)-agonist use in patients with asthma in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021; 126(6):681-9.e1. Analysis of administrative claims data from 135,540 US asthma patients found that exacerbation risk increased with increasing SABA fills.

Nwaru BI, Ekström M, Hasvold P, Wiklund F, Telg G, Janson C. Overuse of short-acting β(2)-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: a nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(4):1901872.

O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, Barnes PJ, Zhong N, Keen C, et al. Inhaled combined budesonide-formoterol as needed in mild asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1865–76.

•• Quint JK, Arnetorp S, Kocks JWH, Kupczyk M, Nuevo J, Plaza V, et al. Short-acting beta-2-agonist exposure and severe asthma exacerbations: SABINA findings from Europe and North America. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022; 10(9):2297-309.e10. Data from the SABINA datasets, including over 1 million patients, revealed that over 40% of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters/year and that increasing SABA exposure is associated with severe exacerbation risk.

Slejko JF, Ghushchyan VH, Sucher B, Globe DR, Lin SL, Globe G, et al. Asthma control in the United States, 2008–2010: indicators of poor asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1579–87.

•• Bateman ED, Price DB, Wang HC, Khattab A, Schonffeldt P, Catanzariti A, et al. Short-acting β(2)-agonist prescriptions are associated with poor clinical outcomes of asthma: the multi-country, cross-sectional SABINA III study. Eur Respir J. 2022; 59(5):2101402. In an analysis of electronic case report forms for 8,351 asthma patients, high SABA prescriptions were associated with poor clinical outcomes in a broad range of settings.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2022. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf.

To T, Zhu J, Terebessy E, Zhang K, Gershon AS, Licskai C. Is overreliance on short-acting β(2)-agonists associated with health risks in the older asthma population? ERJ Open Res. 2022;8(1):00032–2022.

Spitzer WO, Suissa S, Ernst P, Horwitz RI, Habbick B, Cockcroft D, et al. The use of beta-agonists and the risk of death and near death from asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(8):501–6.

Briggs A, Nasser S, Hammerby E, Buchs S, Virchow JC. The impact of moderate and severe asthma exacerbations on quality of life: a post hoc analysis of randomised controlled trial data. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5(1):6.

Tattersfield AE, Postma DS, Barnes PJ, Svensson K, Bauer CA, O'Byrne PM, et al. Exacerbations of asthma: a descriptive study of 425 severe exacerbations. The FACET International Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999; 160(2):594-9.

Baylor Scott White Health. Rules of Two®. 2023. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://www.bswhealth.com/conditions/asthma.

Chipps BE, Murphy KR, Oppenheimer J. 2020 NAEPP guidelines update and GINA 2021-asthma care differences, overlap, and challenges. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(1s):S19-s30.

Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343–73.

Millard M, Hart M, Barnes S. Validation of Rules of Two™ as a paradigm for assessing asthma control. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2014;27(2):79–82.

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. 2020 focused updates to the asthma management guidelines: a report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. 2020. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/2020-focused-updates-asthma-management-guidelines.

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program‚ Third Expert Panel on the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Expert Panel report 3: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2007. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7232/.

• Hesso I, Nabhani Gebara S, Greene G, Co Stello RW, Kayyali R. A quantitative evaluation of adherence and inhalation technique among respiratory patients: an observational study using an electronic inhaler assessment device. Int J Clin Pract. 2020; 74(2):e13437. In a prospective study, objective data from electronic monitoring devices showed significantly lower actual adherence rates compared with other data sources such as dose counters and prescription refills.

Janson C, Menzies-Gow A, Nan C, Nuevo J, Papi A, Quint JK, et al. SABINA: an overview of short-acting β(2)-agonist use in asthma in European countries. Adv Ther. 2020;37(3):1124–35.

• Montero-Arias F, Garcia JCH, Gallego MP, Antila MA, Schonffeldt P, Mattarucco WJ, et al. Over-prescription of short-acting β(2)-agonists is associated with poor asthma outcomes: results from the Latin American cohort of the SABINA III study. J Asthma. 2022:1-14. Data from the SABINA III Latin American cohort show that almost 40% of patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters over 12 months.

Feldman WB, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Switching to over-the-counter availability of rescue inhalers for asthma. Jama. 2022;327(11):1021–2.

Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica, CA, USA: Rand Corp; 2001. Accessed September 27, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269.html.

Barrett D, Heale R. What are Delphi studies? Evid Based Nurs. 2020;23(3):68–9.

Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(6): e20476.

Thompson M. Considering the implication of variations within Delphi research. Fam Pract. 2009;26(5):420–4.

Rahaghi FF, Safdar Z, Brown AW, de Andrade JA, Flaherty KR, Kaner RJ, et al. Expert consensus on the management of adverse events and prescribing practices associated with the treatment of patients taking pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Delphi consensus study. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):191.

Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li JT, Marcus P, et al. Development of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):59–65.

• Worth H, Criée CP, Vogelmeier CF, Kardos P, Becker EM, Kostev K, et al. Prevalence of overuse of short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA) and associated factors among patients with asthma in Germany. Respir Res. 2021; 22(1):108. Data from a German electronic healthcare database show that SABA overuse is prevalent across all GINA steps.

• Akinbami LJ, Salo PM, Cloutier MM, Wilkerson JC, Elward KS, Mazurek JM, et al. Primary care clinician adherence with asthma guidelines: the National Asthma Survey of Physicians. J Asthma. 2020; 57(5):543-55. Data from the National Asthma Survey revealed that adherence to asthma guidelines, particularly those pertaining to patient education and the performance of spirometry, is inconsistent among primary care physicians.

Chapman KR, An L, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Campomanes CM, Espinosa J, Jain P, et al. Asthma patients’ and physicians’ perspectives on the burden and management of asthma. Respir Med. 2021;186: 106524.

•• Mathioudakis AG, Tsilochristou O, Adcock IM, Bikov A, Bjermer L, Clini E, et al. ERS/EAACI statement on adherence to international adult asthma guidelines. Eur Respir Rev. 2021; 30(161):210132. Findings of an ERS/EAACI online HCP survey revealed substantial gaps in the real-world implementation of clinical asthma guidelines.

Reddel HK, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, Bacharier LB, Becker A, Brusselle G, et al. GINA 2019: a fundamental change in asthma management: treatment of asthma with short-acting bronchodilators alone is no longer recommended for adults and adolescents. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(6):1901046.

Vähätalo I, Kankaanranta H, Tuomisto LE, Niemelä O, Lehtimäki L, Ilmarinen P. Long-term adherence to inhaled corticosteroids and asthma control in adult-onset asthma. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00715–2020.

de Las Vecillas L, Quirce S. Landscape of short-acting beta-agonists (SABA) overuse in Europe. Clin Exp Allergy. 2023;53(2):132–44.

• Price D, Jenkins C, Hancock K, Vella R, Heraud F, Le Cheng P, et al. Ending the reign of short-acting β2-agonists in Australia? Respirology. 2023; 28 (Suppl S1):abst: AO01-3. A study found that, despite its existence, self-reporting of SABA overuse was uncommon in asthma.

• Azzi E, Kritikos V, Peters M, Price D, Cvetkovski B, Alphonse PS, et al. Perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of short-acting beta(2) agonist users: an Australian cross-sectional community pharmacy-based study. J Asthma. 2022; 59(1):178-88. A real-world observational study found that SABAs were most likely to be considered by SABA over-users as ‘safe to use’; high SABA users were also the least likely to self-report good or excellent health.

Hong SH, Sanders BH, West D. Inappropriate use of inhaled short acting beta-agonists and its association with patient health status. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(1):33–40.

Bereznicki BJ, Chapman MP, Bereznicki LRE. Factors associated with overestimation of asthma control: a cross-sectional study in Australia. J Asthma. 2017;54(4):439–46.

Fletcher M, Hiles D. Continuing discrepancy between patient perception of asthma control and real-world symptoms: a quantitative online survey of 1,083 adults with asthma from the UK. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(4):431–8.

Murphy KR, Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Nathan RA, Stoloff SW, Doherty DE. Asthma management and control in the United States: results of the 2009 Asthma Insight and Management survey. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33(1):54–64.

Price D, David-Wang A, Cho SH, Ho JC, Jeong JW, Liam CK, et al. Time for a new language for asthma control: results from REALISE Asia. J Asthma Allergy. 2015;8:93–103.

Bosnic-Anticevich S, Kritikos V, Carter V, Yan KY, Armour C, Ryan D, et al. Lack of asthma and rhinitis control in general practitioner-managed patients prescribed fixed-dose combination therapy in Australia. J Asthma. 2018;55(6):684–94.

Stanford RH, Shah MB, D’Souza AO, Dhamane AD, Schatz M. Short-acting β-agonist use and its ability to predict future asthma-related outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109(6):403–7.

Tibble H, Lay-Flurrie J, Sheikh A, Horne R, Mizani MA, Tsanas A. Linkage of primary care prescribing records and pharmacy dispensing records in the Salford Lung Study: application in asthma. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):303.

Barrett MA, Humblet O, Marcus JE, Henderson K, Smith T, Eid N, et al. Effect of a mobile health, sensor-driven asthma management platform on asthma control. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(5):415-21.e1.

Chrystyn H, Saralaya D, Shenoy A, Toor S, Kastango K, Calderon E, et al. Investigating the accuracy of the Digihaler, a new electronic multidose dry-powder inhaler, in measuring inhalation parameters. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2022;35(3):166–77.

• Hoyte FCL, Mosnaim GS, Rogers L, Safioti G, Brown R, Li T, et al. Effectiveness of a digital inhaler system for patients with asthma: a 12-week, open-label, randomized study (CONNECT1). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022; 10(10):2579-87. In a 12-week open-label study, use of an electronic inhaler that provides patients and healthcare professionals with objective usage data was associated with greater odds of clinically meaningful improvement in asthma control.

•• Chan A, De Simoni A, Wileman V, Holliday L, Newby CJ, Chisari C, et al. Digital interventions to improve adherence to maintenance medication in asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022; 6(6):Cd013030. The authors of this Cochrane review of digital interventions to improve adherence in asthma concluded that such interventions may improve adherence, asthma control and quality of life.

Braido F, Chrystyn H, Baiardini I, Bosnic-Anticevich S, van der Molen T, Dandurand RJ, et al. “Trying, but failing” - the role of inhaler technique and mode of delivery in respiratory medication adherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(5):823–32.

Laba TL, Jan S, Zwar NA, Roughead E, Marks GB, Flynn AW, et al. Cost-related underuse of medicines for asthma-opportunities for improving adherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2298-306.e12.

Blaiss M, Oppenheimer J, Corbett M, Bacharier L, Bernstein J, Carr T, et al. Consensus of an ACAAI, AAAAI, and ATS workgroup on definition of clinical remission in asthma on treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023;S1081–1206(23):01218–8.

•• Lugogo NL, DePietro M, Reich M, Merchant R, Chrystyn H, Pleasants R, et al. A predictive machine learning tool for asthma exacerbations: results from a 12-week, open-label study using an electronic multi-dose dry powder inhaler with integrated sensors. J Asthma Allergy. 2022; 15:1623-37. A machine learning model capable of predicting impending asthma exacerbations was developed using data collected by an electronic multi-dose digital inhaler.

Kang HS, Exworthy M. Wearing the future-wearables to empower users to take greater responsibility for their health and care: scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10(7): e35684.

Nasa P, Jain R, Juneja D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: how to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. 2021;11(4):116–29.

Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi technique in health sciences: a map. Front Public Health. 2020;8:457.

•• Canonica GW, Spanevello A, de Llano LP, Domingo Ribas C, Blakey JD, Garcia G, et al. Is asthma control more than just an absence of symptoms? An expert consensus statement. Respir Med. 2022; 202:106942. An expert consensus statement, arrived at using a Delphi-based approach, highlighted the need for clarity on the definition and assessment of asthma control.

• Domingo C, Garcia G, Gemicioglu B, Van GV, Larenas-Linnemann D, Neffen H, et al. Consensus on mild asthma management: results of a modified Delphi study. J Asthma. 2022:1-13. A modified Delphi procedure was used to develop consensus statements on the management of mild asthma.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial support for the development of this manuscript, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Lorna Hepworth, PhD, Jackie Phillipson, PhD, Jane Blackburn, PhD, and Ian C Grieve, PhD, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio company, and funded by Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D Inc. The authors thank Sensified for their contributions to the study, including identification of phase 2 and phase 3 panelists for inclusion based on their expertise in the field, coordination of the meetings, and review of the manuscript. The authors also thank the third-party vendor who assisted with recruitment of the phase 1 participants.

Funding

This study and medical writing support of this article were funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship of this article. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Njira Lugogo, Rajan Merchant, Greg Bensch, Jay Portnoy, John Oppenheimer and Mario Castro. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by Njira Lugogo, Maeve O’Connor, Maureen George, Rajan Merchant, Greg Bensch, Jay Portnoy, John Oppenheimer and Mario Castro. All contributed to the critical review and revision of each version of the manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. All have reviewed and approved this final version and consent to its publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

N. Lugogo received consulting fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Avillion, Genentech, GSK, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Teva; honoraria for non-speakers bureau presentations from GSK and AstraZeneca; and travel support from Astra Zeneca; her institution received research support from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Avillion, Evidera, Gossamer Bio, Genentech, GSK, Regeneron, Sanofi, Novartis and Teva. She is an honorary faculty member of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute but does not receive compensation for this role. M. O’Connor has received honoraria and/or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, BioCryst, CSL Behring, GSK, Pharming Technologies BV, Sanofi, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. M. George has received honoraria and/or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Genentech, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. R. Merchant has received honoraria and/or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Propeller Health, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi. G. Bensch has received honoraria and/or consulting fees from Amgen, Aimimmune, AstraZeneca, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. J. Portnoy has received honoraria and/or consulting fees from BioCryst and Thermo Fisher. J. Oppenheimer has received honoraria and/or consulting fees from Amgen, Aquestive, AstraZeneca, Novartis, GSK, Sanofi, and Regeneron. M. Castro reports institutional grant funding from NIH, ALA, PCORI, AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Pulmatrix, Sanofi-Aventis, and Shionogi. He receives consulting fees from Allakos, Arrowhead, Genentech, GSK, Merck, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva and OM Pharma. He receives payment for speaker’s bureau activities for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Regeneron, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva. He receives royalties from Aer Therapeutics and Elsevier.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported studies/experiments involving human or animal subjects performed by the authors were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lugogo, N., O’Connor, M., George, M. et al. Expert Consensus on SABA Use for Asthma Clinical Decision-Making: A Delphi Approach. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 23, 621–634 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-023-01111-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-023-01111-z