Opinion statement

Preventing depression in cancer patients on long-term opioid therapy should begin with depression screening before opioid initiation and repeated screening during treatment. In weighing the high morbidity of depression and opioid use disorder in patients with chronic cancer pain against a dearth of evidence-based therapies studied in this population, patients and clinicians are left to choose among imperfect but necessary treatment options. When possible, we advise engaging psychiatric and pain/palliative specialists through collaborative care models and recommending mindfulness and psychotherapy to all patients with significant depression alongside cancer pain. Medications for depression should be reserved for moderate to severe symptoms. We recommend escitalopram/citalopram or sertraline among selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), or the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) duloxetine, venlafaxine, or desvenlafaxine if patients have a significant component of neuropathic pain or fibromyalgia. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (consider nortriptyline or desipramine, which have better anticholinergic profiles) should be considered for patients who do not respond to or tolerate SSRI/SNRIs. Existing evidence is inadequate to definitively recommend methylphenidate or novel agents, such as ketamine or psilocybin, as adjunctive treatments for cancer-related depression and pain. Physicians who treat patients with cancer pain should utilize universal precautions to limit the risk of non-medical opioid use (non-medical opioid use). Patients should be screened for non-medical opioid use behaviors at initial consultation and at regular intervals during treatment using a non-judgmental approach that reduces stigma. Co-management with an addiction specialist may be indicated for patients at high risk of non-medical opioid use and opioid use disorder. Buprenorphine and methadone are indicated for the treatment of opioid use disorder, and while they have not been systematically studied for treatment of opioid use disorder in patients with cancer pain, they do provide analgesia for cancer pain. While an interdisciplinary team approach to manage psychological stress may be beneficial, this may not be possible for patients treated outside of comprehensive cancer centers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many cancers and many treatments for cancer are painful. Pain occurs in 50% of patients with cancer, and approximately 10 to 20% experience severe pain [1, 2]. Nearly one-third of cancer survivors experience chronic pain, defined as experiencing pain on most days for 90 days or longer [3]. Pain is frequently treated with prescription opioids. Although opioids are the most effective treatment for moderate to severe pain and are generally safe with short-term use, long-term opioid therapy carries numerous mental and physical health risks, including increased risk for new-onset depression and worsening of existing depression [4,5,6,7,8].

Independent of long-term opioid therapy, depression is common in adult patients with cancer. Depression is prevalent in 20–30% of cancer patients [9] and nearly 25% of patients in palliative settings [10]. Furthermore, depression is undertreated in oncology settings. In a large UK sample, 73% of cancer outpatients with depression were not receiving potentially effective depression treatments [11]. Depression is a risk factor for long-term opioid therapy and a key contributor to adverse opioid-related outcomes such as dependence and overdose [12,13,14,15]. In addition, long-term opioid therapy in non-cancer pain has been shown to increase risk for new-onset and worsening depression [4,5,6,7,8, 16,17,18]. This bi-directional association is consistent with the concept of hyperkatifeia.

Hyperkatifeia

Hyperkatifeia is a term first reported by Shurman and Koob [19, 20••] and derives from the Greek word, katifeia, which means dejection or low emotional state. Hyperkatifeia is a negative emotional state involving malaise, irritability, unease, dysphoria (general dissatisfaction with life), alexithymia (inability to describe emotions), and anxiety [19, 20••]. Although not a diagnosis, hyperkatifeia’s symptoms overlap with depression, anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure), and dysthymia (persistent mild depression).

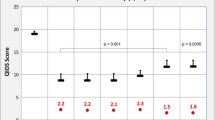

It has been postulated [19, 20••] that hyperkatifeia underlies the negative reinforcement behind drug seeking. In the case of prescription opioids, negative reinforcement in the form of pain and dysphoria during withdrawal motivates opioid use to return to hedonic homeostasis and euthymia. As proposed in Figure 1, with long-term opioid therapy, the ability to experience natural rewards is reduced, and the threshold for feeling normal, or not distressed or depressed, increases. Thus, higher opioid doses are required to maintain homeostasis. Over time, opioids no longer reduce pain and may lead to hyperalgesia and dysphoria. Consequently, negative reinforcement becomes the driver of opioid seeking, as opposed to positive reinforcement from pain relief and opioid-induced euphoria [19, 20••].

Hyperkatifeia in long-term opioid therapy is consistent with epidemiological research demonstrating that psychiatric disorders are associated with an increased risk for long-term opioid use and opioid misuse, abuse, and use disorder [12, 14, 21]. Longer-term use compared to short-term use increases risk for new onset depression, depression recurrence, and worsening depression [4,5,6, 17]. In non-cancer settings, patients who experienced an increase in opioid dose over 2 years were also more likely to have an increase in depression symptoms [22]. Rapid dose escalation vs. stable dose has also been linked to increased risk for new-onset depression [16], as has pre- and post-operative opioid use [7]. A Mendelian randomization study supports a causal association between genetic liability for greater prescription opioid use and risk of major depressive disorder [8]. While hyperkatifeia has not been examined in cancer populations, this model provides an initial framework to understand patterns of opioid use and depression symptoms in cancer pain populations.

Consequences of depression in cancer pain

While studies of long-term opioid use, hyperkatifeia, and depression risk have not been conducted in patients with cancer pain, we can extrapolate findings to this patient population. For patients with cancer, long-term opioid use may lead to depression that in turn complicates recovery and increases risk for mortality. Cancer pain is associated with a 3.5 times greater risk for feeling depressed and 2.5 times risk for feeling anxious [1, 3]. Pain interference continued to predict depression in a sample of largely male patients 1 year after cancer diagnosis [23]. Depression is associated with more than twice the risk of hospitalization for opioid poisoning and opioid abuse or dependence among patients with cancer pain. In a cohort with a mean survival time of 318 days, those with more severe depression symptoms had a 75% increased risk of death [24]. Risk of suicide and suicide mortality is particularly elevated in head and neck cancer patients and might be driven by pain and depression [25, 26]. In patients with advanced cancer, both depression and pain are associated with worse quality of life, with depression identified as the strongest single predictor among a range of factors, including systemic inflammation, physical performance, symptom burden, and comorbidities [27]. A more encouraging implication of this association is that effective treatment of depression also improves cancer pain management. In a study of 274 cancer patients, greater improvement in depression predicted pain improvement over a 12-month period (OR 1.84) [28].

Detecting depression in cancer pain

Pain can mask depression [29], and patients may blame pain for their depression and, as in the case of hyperkatifeia, mistakenly interpret opioid-induced euphoria as an antidepressant effect. A critical first step in mitigating risk of opioid-related emotional disturbance is to screen for depression, dysthymia, and anhedonia, not only before initiating opioids but repeatedly during opioid therapy.

Most opioid renewals require a written prescription, which offers an ideal opportunity to repeat depression screening using valid, brief assessments. Numerous options are available to screen for depression and mood disturbance in chronic pain [30,31,32,33]. The PHQ-2 [34], a two-item depression screener, is the shortest screening instrument and as accurate as the longer PHQ-9 [35] for detecting depression in patients with cancer [30]. Several measures, including the PHQ-9, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20, and Mental Health Inventory-5 are all sensitive in detecting change in depression (improvement, worsening, or no change) among adult cancer patients with pain [31]. Many clinicians and researchers may prefer the PHQ-9 because it is available online and free to use.

While mental health screening in oncology is essential, screening alone is inadequate, and treating professionals need to be identified and engaged. Mental health specialists and psycho-oncologists are limited resources within cancer settings, though the ability to refer out to community psychiatry and psychology or engage in collaborative care models can alleviate this problem [36].

Treating depression in cancer pain

Guidance synthesizing evidence-based treatments for depression in the context of cancer pain is lacking. Practical management guidelines for depression in cancer do not address comorbid cancer pain [37•], and similar guidelines for cancer pain do not include treatment of depression [38]. However, stepped care approaches that guide management of both depression and pain in cancer can be extrapolated to treating depression in patients who also have cancer pain.

Psychosocial interventions are indicated for all classes of depression severity. Mindfulness and psychotherapy (broadly defined) both demonstrate benefit in depression and pain symptoms in patients with cancer, though studies are heterogeneous and evidence quality is low to moderate [39,40,41]. Cognitive behavior therapy, a mainstay in depression across other disease states, has only mixed evidence across cancer subtypes [41,42,43]. Beyond individual interventions, studies consistently demonstrate collaborative care as a superior model to usual treatment in cancer depression [44], with improvements in both depression and pain in the SMaRT Oncology-2 trial [45•]. While there are many collaborative care models for integrating primary care and mental health services, in the present case, collaborative care is a model that provides systematic, psychiatrist-guided depression interventions to a panel of patients, leveraging a limited pool of psychiatrists to provide evidence-driven treatment to more patients. Adapted from primary care to cancer settings, it partners a consulting psychiatrist with a care manager to review cases and engage with oncology medical teams to recommend a treatment plan and monitor response [45•].

Antidepressant medications, established as front-line therapy for depression in multiple disease states, have sparse and low-quality evidence for depression and pain across cancer settings. This includes a lack of benefit against placebo in a 2018 Cochrane review [46•] and inconclusive evidence (data only for amitriptyline and fluvoxamine) when added to opioids for cancer pain [47]. Thus, expert guidance recommends reserving antidepressants for moderate to severe depression in oncology settings [48••]. The SSRIs citalopram/escitalopram and sertraline are considered first-line, due to tolerability and low propensity for drug interactions [49]. SNRIs including duloxetine, venlafaxine/desvenlafaxine, and milnacipran/levomilnacipran, may be more beneficial in patients with comorbid neuropathic cancer pain or fibromyalgia [37, 48••]. The tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine, doxepin, nortriptyline, desipramine) are more poorly tolerated than SSRIs/SNRIs and pose higher risks in cancer patients given anticholinergic properties, cardiac toxicity, and cognitive impacts [50]. Nortriptyline and desipramine are less anticholinergic than others in this class.

Adjunctive, rapidly acting treatments for depression in cancer, such as psychostimulants (methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine) and stimulant-like medications (modafinil, armodafinil), bear consideration in patients with cancer pain given potential benefits for opioid-induced sedation [48••, 51]. Among these medications, data remain inconclusive but are strongest for methylphenidate in the treatment of depression generally [52] and in cancer settings [53].

Novel approaches to managing depression in cancer patients may also be relevant for patients with comorbid cancer pain, though evidence to guide practice is currently insufficient. Ketamine produced resolution of depression and suicidal ideation within 1 day in an RCT of depressed cancer patients [54] and has shown promise in cancer pain across case series and open-label studies. Unfortunately, ketamine failed to show reduced pain or opioid use in a meta-analysis of cancer pain [55], and a 2017 Cochrane review found low-quality, insufficient evidence for ketamine as an adjuvant to opioids in cancer pain [56]. In small clinical trials, psilocybin appears to ameliorate both depression and existential distress in cancer [57, 58]. To date, no published studies report on psilocybin’s impacts on comorbid depression and pain in patients with cancer.

Opioids and opioid use disorder in patients with cancer

Opioid-related mortality is 10 times lower in cancer survivors compared to the general population [59]. However, opioid-related deaths are increasing in cancer patients, which are thought to be related to increases in survival and subsequently higher levels of chronic pain and long-term opioid therapy [59]. With greater oversight on opioid prescribing, many clinicians have expressed concerns about undertreated cancer pain [60].

While opioids are the mainstay of treatment for cancer pain [61], oncologists do not know which patients they treat will become cancer survivors and whether they will develop non-medical opioid use behaviors [62]. Non-medical opioid use is the use of opioids without a prescription or in ways other than medically prescribed, including for the experience or feeling caused by the opioid [63]. The spectrum of non-medical opioid use may have features of varying degrees of opioid use disorder.

In a systematic review of 28 studies, Yusufov and colleagues [64••] found that substance use rates (variably reported, ranging from any substance use to a formal use disorder) ranged from 2 to 35% in cancer patients, with a median prescribed opioid rate of 18% across 7 studies reviewed. Survivors of cancer are also at risk of non-medical opioid use and opioid use disorder. In one study, the rate of opioid prescribing among cancer survivors was 1.22 times higher than among matched controls (95% CI, 1.11–1.3) [65]. Despite the potential risk and prevalence of opioid use disorder among patients with cancer and cancer survivors, there is a lack of confidence and training in providers managing opioid use disorder in patients with cancer [66, 67].

Compared to guidelines in patients with non-cancer pain, the best practices for identifying and providing optimal management of non-medical opioid use are less clearly defined for patients with cancer pain [68, 69••]. For example, existing CDC guidelines for safe opioid prescribing exclude patients with cancer-related pain who have distinct pain management needs that may require relatively high doses of opioids [69••, 70]. In addition, there is little outcomes-based research on how to manage non-medical opioid use in palliative care settings [64••].

Clinicians are encouraged to adopt universal precautions adapted from chronic non-cancer pain settings as their clinical framework for assessing and managing cancer-related pain [68, 71]. Adapted universal precautions include screening all patients for opioid misuse using brief tools, discussing the risks, benefits, adverse effects and alternatives of opioid therapy, and providing education on safe use, storage, and disposal [68, 72,73,74]. Screening for opioid use disorder should be done at initial consultation and regularly throughout treatment using a non-judgmental approach that allows patients the freedom to disclose if they are struggling with non-medical opioid use. Patients with risk factors for non-medical opioid use, such as a history of chronic non-cancer pain requiring opioids or comorbid psychiatric issues, should be referred to a specialist palliative care clinic or cancer pain clinic for co-management [69••, 74].

In a narrative review of non-medical opioid use, Ulker and Del Fabbro provide best practice recommendations on management of non-medical opioid use in patients with cancer-related pain [69••]. First, educational tools in the form of pamphlets or digital communication should be available for patients and their families about safe use, storage, and disposal of opioids. Strategies to mitigate the risk of non-medical opioid use and diversion include using pill counts and physician review of prescription drug monitoring systems that can provide information on whether the patient is receiving prescriptions from multiple providers or are being co-prescribed medications that increase the chance of overdose. The role of urine drug screens as a management strategy for reducing non-medical opioid use risk is unclear. There is weak evidence supporting the use of urine screens among patients with non-cancer pain and no current guidelines for patients with cancer [73].

Opioid agonists, including partial agonists like buprenorphine and full agonists like methadone, may have an important role in patients with cancer-related pain. Both medications are effective analgesics [75] and are also indicated treatments for opioid use disorder [76]. While a 2015 Cochrane review found that buprenorphine provides effective strong pain relief and offers an advantage of transdermal formulations, its role in the treatment of cancer pain is still evolving due to limited evidence [77]. In an updated Cochrane review, methadone was found to have similar benefits to morphine and was determined to have a role in the management of cancer pain based on low-quality evidence [78]. No systematic reviews have evaluated buprenorphine or methadone for treatment of opioid use disorder among patients with cancer. If patients require methadone or buprenorphine specifically for treatment of opioid use disorder, co-management with an addiction specialist may be indicated.

Use of adjuvant medications may reduce non-medical opioid use. However, research in this area is limited. A systematic review and meta-analysis of non-opioid analgesics in palliative medicine found evidence supporting pain reduction with the use of NSAIDs, but not with acetaminophen, either alone or in combination with strong opioids [79]. Another harm reduction strategy is limiting the use of sedatives, such as benzodiazepines, in combination with opioids, due to the increased risk of overdose death [80].

A key part of management of non-medical opioid use and opioid use disorder in cancer patients is managing psychological and spiritual distress, both of which can amplify expression of pain. In one small trial, patients with cancer pain who participated in an interdisciplinary intervention provided by a specialized team called the Compassionate High Alert Team (CHAT) had a significant reduction in the median (range) number of aberrant behaviors from 3 (1–6) pre-intervention to 0.4 (0–3) post-intervention (p<0.0001) [81•]. A modified version of the CHAT intervention has been implemented using telehealth visits to address non-medical opioid use among patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic [82]. Case et al. [83] present the PARTNERS framework that deploys an interdisciplinary team of providers to support patients with cancer pain and opioid use disorder, using motivational interviewing to elicit and understand the patient’s perspectives and values to facilitate change. However, this approach has not been systematically studied. Individual clinicians who care for patients with cancer with non-medical opioid use should also be familiar with using approaches such as brief motivational interviewing, which is effective among certain populations but has not been evaluated in patients with cancer [69••, 84].

Conclusions

Beyond facing the direct challenges of cancer, oncology patients also bear increased risks of depression, pain, and the need for long-term opioids, which can predispose them to non-medical opioid use and opioid use disorder. The model of hyperkatifeia, while not yet studied in cancer, provides a theoretical framework for the role of long-term opioid therapy in depression and non-medical opioid use. Further research is needed as opioids remain a common approach to managing pain in cancer survivors, who now number about 17 million in the USA [85]. Understanding the interplay of these challenges, as well as their impacts on morbidity and mortality in cancer populations, empowers medical and psychosocial oncology providers to screen for, identify, and treat depression and opioid use disorder in patients with cancer pain. Recognizing a lack of clinical trials directly studying treatment of depression and opioid use disorder in cancer pain, we advocate for an increased research focus in this field.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Cramer JD, Johnson JT, Nilsen ML. Pain in head and neck cancer survivors: prevalence, predictors, and quality-of-life impact. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(5):853–8.

Osazuwa-Peters N, Polednik KM, Tutlam NT, Tait R, Scherrer J, Barnes JM, et al. Depression, chronic pain, and high-impact chronic pain among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39.

Sanford NN, Sher DJ, Butler SS, Xu X, Ahn C, Aizer AA, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain among cancer survivors in the United States, 2010-2017. Cancer. 2019;125(23):4310–8.

Scherrer JF, Svrakic DM, Freedland KE, Chrusciel T, Balasubramanian S, Bucholz KK, et al. Prescription opioid analgesics increase the risk of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(3):491–9.

Scherrer JF, Salas J, Copeland LA, Stock EM, Ahmedani BK, Sullivan M, et al. Prescription opioid duration, dose, and increased risk of depression in 3 large patient populations. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:54–62.

Scherrer JF, Salas J, Copeland LA, Stock EM, Schneider FD, Sullivan M, et al. Increased risk of depression recurrence after initiation of prescription opioids in noncancer pain patients. J Pain. 2016;17(4):473–82.

Wilson L, Bekeris J, Fiasconaro M, Liu J, Poeran J, Kim DH, et al. Risk factors for new-onset depression or anxiety following total joint arthroplasty: the role of chronic opioid use. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019.

Rosoff DB, Smith GD, Lohoff FW. Prescription opioid use and risk for major depressive disorder and anxiety and stress-related disorders: a multivariable Mendelian randomization analysis. JAMA psychiatry. 2021;78(2):151–60.

Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2-3):343–51.

Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–74.

Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P, Symeonides S, Ramessur R, Murray G, et al. Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):343–50.

Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Fan MY, Devries A, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Risks for opioid abuse and dependence among recipients of chronic opioid therapy: results from the TROUP study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(1-2):90–8.

Grattan A, Sullivan MD, Saunders KW, Campbell CI, Von Korff MR. Depression and prescription opioid misuse among chronic opioid therapy recipients with no history of substance abuse. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(4):304–11.

Howe CQ, M.D. S. The missing ‘P’ in pain management: how the current opioid epidemic highlights the need for psychiatric services in chronic pain care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(1):99–104.

Sullivan MD. Depression effects on long-term prescription opioid use, abuse, and addiction. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(9):878–84.

Salas J, Scherrer JF, Schneider FD, Sullivan MD, Bucholz KK, Burroughs T, et al. New-onset depression following stable, slow, and rapid rate of prescription opioid dose escalation. Pain. 2017;158(2):306–12.

Scherrer JF, Salas J, Sullivan MD, Schneider FD, Bucholz KK, Burroughs T, et al. The influence of prescription opioid use duration and dose on development of treatment resistant depression. Prev Med. 2016;91:110–6.

Scherrer JF, Salas J, Lustman PJ, Burge S, Schneider FD, Investigators rRNoTR. Change in opioid dose and change in depression in a longitudinal primary care patient cohort. Pain. 2015;156:348–55.

Shurman J, Koob GF, Gutstein HB. Opioids, pain, the brain, and hyperkatifeia: a framework for the rational use of opioids for pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(7):1092–8.

•• Koob GF. Drug addiction: hyperkatifeia/negative reinforcement as a framework for medications development. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(1):163–201 Comprehensive review of addiction process in context of negative reinforcement.

Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Zhang L, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Association between mental health disorders, problem drug use, and regular prescription opioid use. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(19):2087–93.

Scherrer JF, Salas J, Lustman PJ, Burge S, Schneider FD. Residency Research Network of Texas I. Change in opioid dose and change in depression in a longitudinal primary care patient cohort. Pain. 2015;156(2):348–55.

Bamonti PM, Moye J, Naik AD. Pain is associated with continuing depression in cancer survivors. Psychol Health Med. 2018;23(10):1182–95.

Reyes CC, Anderson KO, Gonzalez CE, Ochs HC, Wattana M, Acharya G, et al. Depression and survival outcomes after emergency department cancer pain visits. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9(4):e36.

Osazuwa-Peters N, Simpson MC, Zhao L, Boakye EA, Olomukoro SI, Deshields T, et al. Suicide risk among cancer survivors: head and neck versus other cancers. Cancer. 2018;124(20):4072–9.

Osazuwa-Peters N, Barnes JM, Okafor SI, Taylor DB, Hussaini AS, Adjei Boakye E, et al. Incidence and risk of suicide among patients with head and neck cancer in rural, urban, and metropolitan areas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021.

Grotmol KS, Lie HC, Hjermstad MJ, Aass N, Currow D, Kaasa S, et al. Depression: a major contributor to poor quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;54(6):889–97.

Wang HL, Kroenke K, Wu J, Tu W, Theobald D, Rawl SM. Predictors of cancer-related pain improvement over time. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(6):642–7.

Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–45.

Wagner LI, Pugh SL, Small W Jr, Kirshner J, Sidhu K, Bury MJ, et al. Screening for depression in cancer patients receiving radiotherapy: feasibility and identification of effective tools in the NRG Oncology RTOG 0841 trial. Cancer. 2017;123(3):485–93.

Johns SA, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Theobald DE, Wu J, Tu W. Longitudinal comparison of three depression measures in adult cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2013;45(1):71–82.

Kroenke K, Yu Z, Wu J, Kean J, Monahan PO. Operating characteristics of PROMIS four-item depression and anxiety scales in primary care patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1892–901.

Kroenke K, Stump TE, Chen CX, Kean J, Damush TM, Bair MJ, et al. Responsiveness of PROMIS and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) depression scales in three clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):41.

Lowe B, Kroenke K, Grafe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:163–71.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9 validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Holtzman AL, Pereira DB, Yeung AR. Implementation of depression and anxiety screening in patients undergoing radiotherapy. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(2):e000034.

• Li M, Kennedy EB, Byrne N, Gerin-Lajoie C, Katz MR, Keshavarz H, et al. Management of depression in patients with cancer: a clinical practice guideline. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(8):747–56 Clinical guidelines on treating depression in cancer based on systematic review of RCTs and existing evidence.

Swarm RA, Paice JA, Anghelescu DL, Are M, Bruce JY, Buga S, et al. Adult cancer pain, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2019;17(8):977–1007.

Zhang MF, Wen YS, Liu WY, Peng LF, Wu XD, Liu QW. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapy for reducing anxiety and depression in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(45):e0897–0.

Poulin PA, Romanow HC, Rahbari N, Small R, Smyth CE, Hatchard T, et al. The relationship between mindfulness, pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, depression, and quality of life among cancer survivors living with chronic neuropathic pain. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(10):4167–75.

Okuyama T, Akechi T, Mackenzie L, Furukawa TA. Psychotherapy for depression among advanced, incurable cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;56:16–27.

Tatrow K, Montgomery GH. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques for distress and pain in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2006;29(1):17–27.

Serfaty M, King M, Nazareth I, Moorey S, Aspden T, Mannix K, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression in advanced cancer: CanTalk randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;216(4):213–21.

Li M, Kennedy EB, Byrne N, Gerin-Lajoie C, Katz MR, Keshavarz H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of collaborative care interventions for depression in patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2017;26(5):573–87.

• Sharpe M, Walker J, Holm Hansen C, Martin P, Symeonides S, Gourley C, et al. Integrated collaborative care for comorbid major depression in patients with cancer (SMaRT Oncology-2): a multicentre randomised controlled effectiveness trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1099–108 Large RCT demonstrating collaborative care beneficial for depression and pain in cancer.

• Ostuzzi G, Matcham F, Dauchy S, Barbui C, Hotopf M. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD011006 Very low quality evidence for antidepressants vs. placebo in patients with cancer in systematic review.

Bennett MI. Effectiveness of antiepileptic or antidepressant drugs when added to opioids for cancer pain: systematic review. Palliat Med. 2011;25(5):553–9.

•• Grassi L, Nanni MG, Rodin G, Li M, Caruso R. The use of antidepressants in oncology: a review and practical tips for oncologists. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(1):101–11 Synthesis of 30 years of data recommending antidepressants for severe depression in cancer, cautions side effects and interactions.

Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2018;361:k1415.

Ahmed E. Antidepressants in patients with advanced cancer: when they’re warranted and how to choose therapy. Oncology (Williston Park). 2019;33(2).

Andrew BN, Guan NC, Jaafar N. The use of methylphenidate for physical and psychological symptoms in cancer patients: a review. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(8):877–87.

Bahji A, Mesbah-Oskui L. Comparative efficacy and safety of stimulant-type medications for depression: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:416–23.

Ng CG, Boks MP, Roes KC, Zainal NZ, Sulaiman AH, Tan SB, et al. Rapid response to methylphenidate as an add-on therapy to mirtazapine in the treatment of major depressive disorder in terminally ill cancer patients: a four-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(4):491–8.

Fan W, Yang H, Sun Y, Zhang J, Li G, Zheng Y, et al. Ketamine rapidly relieves acute suicidal ideation in cancer patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Oncotarget. 2017;8(2):2356.

Jonkman K, van de Donk T, Dahan A. Ketamine for cancer pain: what is the evidence? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2017;11(2):88–92.

Bell RF, Eccleston C, Kalso EA. Ketamine as an adjuvant to opioids for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD003351.

Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181–97.

Agin-Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, Mennenga SE, Ponte KL, Guss J, et al. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. J Psychopharmacol. 2020;34(2):155–66.

Chino F, Kamal A, Chino J. Incidence of opioid-associated deaths in cancer survivors in the United States, 2006-2016: a population study of the opioid epidemic. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1100–2.

Vitzthum LK, Riviere P, Murphy JD. Managing cancer pain during the opioid epidemic-balancing caution and compassion. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(7):1103–4.

About the WHO WMH-CIDI: World Health Organization World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO WMH-CIDI); [Available from: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi/about-the-who-wmh-cidi/.

Loren AW. Harder to treat than leukemia - opioid use disorder in survivors of cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2485–7.

Voon P, Kerr T. “Nonmedical” prescription opioid use in North America: a call for priority action. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013;8:39.

•• Yusufov M, Braun IM, Pirl WF. A systematic review of substance use and substance use disorders in patients with cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;60:128–36 Systematic review revealing high prevalence of substance use disorder in cancer patients.

Sutradhar R, Lokku A, Barbera L. Cancer survivorship and opioid prescribing rates: a population-based matched cohort study among individuals with and without a history of cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(21):4286–93.

Merlin JS, Patel K, Thompson N, Kapo J, Keefe F, Liebschutz J, et al. Managing chronic pain in cancer survivors prescribed long-term opioid therapy: a national survey of ambulatory palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2019;57(1):20–7.

Childers JW, Arnold RM. “I feel uncomfortable ‘calling a patient out’”: educational needs of palliative medicine fellows in managing opioid misuse. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(2):253–60.

Carmichael AN, Morgan L, Del Fabbro E. Identifying and assessing the risk of opioid abuse in patients with cancer: an integrative review. Subst Abus Rehabil. 2016;7:71–9.

•• Ulker E, Del Fabbro E. Best practices in the management of nonmedical opioid use in patients with cancer-related pain. Oncologist. 2020;25(3):189–96 Narrative review and best practice recommendations for NMOU management in oncology.

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–45.

Paice JA, Portenoy R, Lacchetti C, Campbell T, Cheville A, Citron M, et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(27):3325–45.

Arthur J, Bruera E. Balancing opioid analgesia with the risk of nonmedical opioid use in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(4):213–26.

Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, Diamant AL, Doyle B, Di Capua P, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1):38–47.

Del Fabbro E. Assessment and management of chemical coping in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1734–8.

Davis MP, Pasternak G, Behm B. Treating chronic pain: an overview of clinical studies centered on the buprenorphine option. Drugs. 2018;78(12):1211–28.

Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–6.

Schmidt-Hansen M, Bromham N, Taubert M, Arnold S, Hilgart JS. Buprenorphine for treating cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(3):CD009596.

Nicholson AB, Watson GR, Derry S, Wiffen PJ. Methadone for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD003971.

Schuchen RH, Mucke M, Marinova M, Kravchenko D, Hauser W, Radbruch L, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on non-opioid analgesics in palliative medicine. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9(7):1235–54.

Hernandez I, He M, Brooks MM, Zhang Y. Exposure-response association between concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use and risk of opioid-related overdose in Medicare Part D beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180919.

• Arthur J, Edwards T, Reddy S, Nguyen K, Hui D, Yennu S, et al. Outcomes of a specialized interdisciplinary approach for patients with cancer with aberrant opioid-related behavior. Oncologist. 2018;23(2):263–70 Interdisciplinary intervention associated with reduction inaberrants opioid related behavior in cancer patients.

Amaram-Davila JS, Arthur J, Reddy A, Bruera E. Managing nonmedical opioid use among patients with cancer pain during the COVID-19 pandemic using the CHAT model and telehealth. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2021;62(1):192–6.

Case AA, Walter M, Pailler M, Stevens L, Hansen E. A practical approach to nonmedical opioid use in palliative care patients with cancer: using the PARTNERS framework. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020;60(6):1253–9.

Darker CD, Sweeney B, Keenan E, Whiston L, Anderson R, Barry J. Screening and brief interventions for illicit drug use and alcohol use in methadone maintained opiate-dependent patients: results of a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial feasibility study. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51(9):1104–15.

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363–85.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Nicole Bates is supported, in part, by a National Cancer Institute (NCI) funded clinical trial (NCT05012124). Jennifer K. Bello declares that she has no conflict of interest. Nosayaba Osazuwa-Peters is supported, in part, by a grant (K01DE030916) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Mark Sullivan is supported, in part, by a grant (R01DA043811) from the NIH; and is a board member of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing. This is an unpaid advisory position. Jeffrey F. Scherrer is supported, in part, by a grant (R01DA043811) from the NIH.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Palliative and Supportive Care

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bates, N., Bello, J.K., Osazuwa-Peters, N. et al. Depression and Long-Term Prescription Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder: Implications for Pain Management in Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options in Oncol. 23, 348–358 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-022-00954-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-022-00954-4