Opinion statement

Palliative care integrated into standard medical oncologic care will transform the way we approach and practice oncologic care. Integration of appropriate components of palliative care into oncologic treatment using a pathway-based approach will be described in this review. Care pathways build on disease status (early, locally advanced, advanced) as well as patient and family needs. This allows for an individualized approach to care and is the best means for proactive screening, assessment, and intervention, to ensure that all palliative care needs are met throughout the continuum of care. Components of palliative care that will be discussed include assessment of physical symptoms, psychosocial distress, and spiritual distress. Specific components of these should be integrated based on disease trajectory, as well as clinical assessment. Palliative care should also include family and caregiver education, training, and support, from diagnosis through survivorship and end of life. Effective integration of palliative care interventions have the potential to impact quality of life and longevity for patients, as well as improve caregiver outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lung cancer is a devastating disease and is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the USA [1]. The last few decades has shown an accelerated rise in technologies and therapies in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treatment. Current oncology care focuses on treatment choices that include radiation therapy, interventional procedures including surgery, and systemic therapy [2]. Despite these advances, patients with NSCLC face many challenges that are not addressed by our current model of care. NSCLC patients experience high symptom burden, rapidly declining functional status, social decline, psychological symptoms including emotional and spiritual angst, and often confront a poor prognosis.

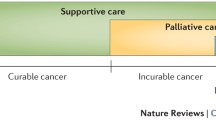

Palliative care focuses on relief of symptoms across the physical and psychosocial domains and promotes shared decision-making. Palliative care services should also include relief and support for family members and caregivers. Although traditionally implemented late in a patients’ disease course, palliative care is gaining momentum and has the potential not only to affect a patients’ quality of life but also to significantly alter disease trajectory, and may even prolong survival [3, 4••, 5]. Services must be rendered to patients across the spectrum of disease and fine-tuned according to a patient’s individual needs. Importantly, as the world moves toward delivering more fiscally responsible, high value care, the integration of palliative care into oncologic care has the potential for improving quality of care as well [6–9].

The purpose of this review is to take a comprehensive look at the relevant published studies since 2000 to highlight some of the main advances and potential impact of palliative care integration into the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This data will be used to provide recommendations on palliative care interventions to be included as part of care pathways for patients with NSCLC.

Palliative therapies

Physical symptoms

Physical symptom burden in NSCLC patients is high and negatively impacts quality of life [10, 11•, 12]. Pain, dyspnea, cough, anorexia/cachexia, and fatigue are the five most common and distressing symptoms [13]. Patients with early-stage lung cancer may experience minimal symptoms; however, as the disease becomes more advanced, symptoms are more prevalent. An integrated palliative approach to care would include validated instruments to measure symptom severity routinely. Subsequent referral to specialist care when symptoms become more severe or complex is recommended.

Potential palliative therapeutic approaches to assessing and managing these common symptoms are outlined below.

Exercise

Fatigue is a common symptom experienced by the NSCLC population that has an impact on the ability to exercise and maintain functional status. Individuals with NSCLC engaged in less physical activity to similar aged healthy individuals. They also had higher levels of depression, spent less time outdoors, and had lower motivation to engage in exercise [14]. Patients who have undergone lung resection therapy show deterioration in walking distance [15]. Patients with inoperable lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy tend to be more debilitated [16].

Based off growing data, promotion of physical activity is justified, feasible, and well tolerated during and after cancer therapy. Interventions, both pre- and post-operatively, have shown positive benefits including in cancer-related fatigue severity, emotional well-being, functional status, and overall quality of life. Patients who were referred earlier in the course of their treatments were more likely to adhere to and tolerate physical activity [17•, 18, 19]. In the post-surgical setting, several studies have demonstrated the positive effects of exercise programs on endurance and other quality of life parameters [20–23]. Therefore, early referral to physical therapy for tailored physical activity recommendations should be incorporated into NSCLC patient care.

Nutrition

Patients with lung cancer often experience anorexia and cachexia [24–26]. Together, these constitute the cancer anorexia–cachexia syndrome (CACS), a state of muscle catabolism and weight loss experienced as appetite loss [27].

Weight loss and malnutrition have been associated as independent risk factors for post-surgical complications such as intensive care support and post-operative death [28–30]. Data suggests that weight loss during concurrent chemoradiation therapy for NSCLC starts early and prior to onset of symptoms [31]. These symptoms may also have a prognostic impact on patients receiving chemotherapy in advanced disease [32].

Additionally, in advanced disease, the impact of these symptoms can be profound and can impact ability to deliver appropriate disease-modifying therapies [33, 34]. It has also been noted that people with advanced cancer are often found to have fatty acid deficiency [35], which in various studies has been shown to affect nutritional status, functional status, physical activity, and quality of life in lung cancer patients during multimodality treatment [36, 37].

Research suggests that interventions such as assessment of nutritional imbalances and supplementation with appropriate nutrients should be done early and reevaluated throughout illness trajectory [38, 39]. The use of validated assessment instruments such as the FAACT scale in patients with CACS should be utilized to standardize management and follow-up effects of nutritional interventions [40–42].

Pain management

Approximately 75 % of all cancer patients live with chronic pain. Pain is the most common symptom for patients with NSCLC, and they experience acute and chronic pain largely in the chest and lumbar regions [43–45]. Chest pain is present in an estimated 20 % of patients with lung cancer, and this pain increases in severity as the disease progresses [46]. Pain is multifactorial, and thus, often requires a multidisciplinary approach to successful management [47, 48].

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Analgesic Ladder for Cancer Pain Relief is a cornerstone guide for pain management for patients with cancer, regardless of diagnosis. The ladder describes pain management in a series of steps as follows: (1) the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); (2) weak opioid analgesics; and (3) strong opioid analgesics such as morphine, oxycodone, or fentanyl [49]. Breakthrough pain, or a temporary intensification of pain during opioid therapy, may occur and is usually alleviated with immediate release opioids such as fentanyl [47]. Adjuvant analgesics such as anti-depressants and anti-convulsants can supplement opioid use at any stage [50].

While opioids are the mainstay of pain management, special considerations must be taken to mitigate side effects. Titration and monitoring is critical to account for tolerance and metabolic concerns, such as renal insufficiency. Additionally, meta-analyses have indicated that opioid use has resulted in constipation in an average of 41 % of patients. Thus, laxatives are recommended alongside opioid use to prevent opioid-induced constipation [51].

More complex cases of refractory pain during the use of analgesics have shown to benefit from interventional strategies. Radiofrequency ablation is one way to treat pain due to metastases. In one 2015 study of 12 patients with rib metastases, pain reported via a visual analogue scale decreased from 7.9 to 3.4 with no symptomatic complications [52]. For patients experiencing bone metastases, radiation therapy is indicated. While questions remain as to the optimal dose and schedule, approximately 40 % of lung cancer patients receive radiotherapy, and a majority of these are with palliative intent [53, 54]. Additionally, complementary therapies such as mind-body modalities, massage, and acupuncture have been accessed by up to 60 % of cancer patients and have shown a significant benefit [55].

Respiratory support

NSCLC patients often experience a respiratory symptom cluster characterized by dyspnea and cough, manifesting especially in advanced disease. The prevalence of dyspnea alone is estimated between 55 and 87 % throughout all stages of lung cancer [56–59]. Dyspnea correlates with coping capacity, performance status, and other symptoms such as anxiety, depression, fatigue, and cough [60]. Further, dyspnea has been shown to account for over 25 % of urgent care visits in a study of 114 patients with NSCLC, second only to pain [61].

Management of dyspnea relies on the immediate treatment of breathlessness with medication and oxygen/air therapy, as well as pulmonary rehabilitation including exercises, breathing retraining, and smoking cessation [58]. Studies have indicated that a combination of pharmaceutical treatment of underlying causes and longer-term therapies for symptom suppression are the most effective [62]. These strategies have been shown to reduce breathlessness, fatigue, and accompanying anxiety while increasing endurance, functional status, and quality of life [58].

Oxygen therapy is a standard of care for patients requiring respiratory support [63]. Portable oxygen or high-flow oxygen may be indicated based on a patient’s oxygen saturation levels. Patients who are not hypoxemic may receive similar relief of dyspnea using high-flow room air as high-flow oxygen [64].

In patients with refractory dyspnea who no longer experience benefits from portable or high-flow oxygen, opioids are indicated [65]. A review of the use of opioids in the management of dyspnea found that oral opioids, specifically systemic opioids such as once-daily morphine, could increase comfort and decrease the sensation of breathlessness [66, 67••].

Non-pharmacological therapies that have resulted in symptom management are largely based in exercises for endurance and breathing efficiency, management of psychological distress, and lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation [67••]. Evidence suggests that exercises such as pursed lip and diaphragmatic breathing are effective in alleviating dyspnea [67••]. Activities to reduce distress and improve self-efficacy include breathing exercises, relaxation techniques, and psychological support provide an additive and lasting therapeutic effect while promoting self-efficacy in managing dyspnea [67••, 68].

Psychosocial distress

Palliative care should not only address disease-specific physical complaints and symptoms but should also include assessment of psychological, social, spiritual, and financial well-being [69, 70]. Psychosocial status appears to mirror physical decline, particularly surrounding key transition points in a patient’s disease course; namely, at time of diagnosis, discharge after treatment, as disease progresses, and at end of life. These may be the time periods to focus palliative care interventions [71].

For example, it is known that depression and anxiety are common and persistent symptoms experienced by patients diagnosed with NSCLC ranging in prevalence between 25 and 50 % and persistent in approximately 50 % of patients, especially among those with more severe symptoms or functional limitations [72–74]. There have been several studies linking the presence of depression as a predictor of worse survival in cancer, including in newly diagnosed metastatic NSCLC [75–77]. Another study suggests that the presence of anxiety, depression, and worse psychological quality of life during early stage of treatment was associated more with receipt of chemotherapy at the end of life [78]. A patients’ specific coping style may be impacted by their mental health and likely has repercussions on medical decision-making and disease trajectory [79, 80].

Comprehensive validated assessment instruments to measure psychological distress such as the distress thermometer should be used. In addition to screening for depression and anxiety, other areas of concern include family relationships, emotional functioning, lack of information regarding diagnosis/treatment, and practical problems such as financial issues or child care [81]. Referrals to appropriate specialists, which include social workers, specialized nurses, care coordinators or case managers, financial specialists, mental health professionals or spiritual counselors should then be made based on initial assessment.

Smoking cessation

Although decreasing, approximately 16.8 % of the adult US population still smokes cigarettes [82]. Smoking is a known risk factor for NSCLC with current smoking status conferring a worse overall survival and disease-free survival [83]. Smoking is also a known factor associated with increased risk of developing mutations such as KRAS and p53 known to be associated with NSCLC [84, 85]. Chronic nicotine exposure impacted response to therapy in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patents receiving targeted therapy, thus impacting disease trajectory [86]. An association between smoking and the development of NSCLC-COPD has been studied [87].

Furthermore, studies have shown that second primary lung cancers were rare in non-smokers but were associated with increased risk of occurring with increased tobacco exposure. In contrast, non-smokers, former smokers, and recent quitters showed a significant better prognosis [88]. Data also exists that links longer time since cessation of smoking to improve survival outcomes for NSCLC patients with early disease [89]. Patients who quit smoking after the diagnosis of NSCLC maintain better performance status [90]. Given such overwhelming evidence, it is clear that smoking cessation should be prioritized in the care of all patients, and especially in the NSCLC population.

Smoking cessation is more effective with a combined non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic approach. The National Cancer Institute recommends a five-step behavior change process which includes asking the patient about their smoking status, assessing their willingness to make a quite attempt, advising them to stop, assisting them with cessation efforts, and arranging follow-up. Individual and/or group therapy is often appropriate in addition to nicotine replacement therapy, which is the mainstay of pharmacologic treatment. Other medications such as bupropion and varenicline are available, as well as nortryptiline and clonidine, which are available off label for this purpose. Routine follow-up is recommended as the more extensive the support, the higher the likelihood of successful cessation [91–93].

Spiritual health

Palliative care interventions should include content that targets the spiritual needs of patients, their family members, and caregivers. Spirituality is multidimensional, encompassing constructs such as faith and meaning, which may or may not be connected to religious affiliations [94]. Religiousness and spirituality improved depressive symptoms and may ease end of life distress. Women in particular may benefit from spiritual support as they reported more intense problems with emotional functioning and showed benefit from supportive spiritual care [95, 96]. Attempts should be made for providers to use validated assessment instruments such as the FICA to quantitatively measure and track spiritual well-being through treatment course and afterward [97]. Dependent on results of a needs assessment, engaging spiritual care specialists should be considered.

Considering the continuum

Early-stage disease pathway and survivorship

Patients with early-stage NSCLC have disease limited either to the lung (0, IA, IB) or local spread to lymph nodes located on the same side of the chest to where the cancer started (IIA). When possible, early-stage disease is treated with surgery to resect the tumor with 5-year survival approximated at approximately 50 % [98].

Given that surgery is the mainstay of therapy for this stage of disease, perioperative risk stratification and risk modification are important. Assessment of physical symptoms, psychosocial distress, spiritual distress, and caregiver distress should be a common practice for all. However, focus on nutritional and exercise therapy interventions, along with support for smoking cessation, are the mainstay of palliative therapy for this stage. Clinicians and patients should participate in shared decision-making with the initiation of advance care planning efforts.

A survivorship plan should also be developed for patients and families. Survivors face significant challenges post-treatment. Fatigue and respiratory symptoms are the most prevalent physical symptoms among NSCLC survivors and are associated with functional impairment. A comprehensive approach to treatment of these symptoms also includes management of anxiety, depression, and pulmonary disorders [99]. Structured exercise programs can improve physical functioning, mood, respiratory distress, and sleep efficiency [100–102]. Referral to physical activity and pulmonary rehabilitation programs may promote higher quality of life outcomes [103].

Other concerns for lung cancer patients post-treatment include psychological distress, depression, financial issues, and fear of recurrence of NSCLC or secondary malignancies [104••]. Psychosocial support, including mental health support, spiritual support, caregiver support, and financial advice, should be offered alongside continued medical management of symptom sequelae.

Adherence to recommendations on surveillance for recurrence and second primary lung cancers should be followed. The majority of second primary lung cancers and recurrences were detected by post-therapeutic surveillance computed tomography (CT) scans. The highest risk of recurrence persisted in the first 2–4 years following resection with curative intent [105–107]. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery recommends that long-term lung cancer survivors have low-dose CT to detect second primary lung cancer until the age of 79 years [108].

Locally advanced disease pathway

For patients with locally advanced disease, treatment can be complex and includes a combination of radiation therapy, systemic therapy, and surgical interventions, often in sequence or combination [109]. As such, in addition to the standard clinical assessments and palliative interventions above, there is a greater need to coordinate a larger multidisciplinary team often involving medical oncologists, radiation specialists, and surgeons. Discussion of cases in multidisciplinary team meeting forums has shown evidence for better treatment tolerability and outcomes [110]. The evidence from several studies suggest that earlier integration of specialist palliative care team in this collaborative team environment is feasible and has a beneficial impact on symptoms and other quality of life measures [111, 112, 113••].

Advanced disease pathway

The goal of treatment in advanced disease is prolongation of quality of life in the context of patient goals and values. Family and caregiver distress is often more acute, and the need for training, education, and support through treatment, end of life, and bereavement is critical. The more common therapeutic strategies in this setting include radiation for the purposes of palliation of symptoms and systemic therapy.

Radiation therapy has shown associated improvements in several physical symptoms including pain, dyspnea, cough, and more moderately in fatigue and appetite loss [114–116]. Overall improvements in physical, cognitive, social, and emotional functioning were noted, along with beneficial effects on overall global quality of life [117, 118].

The mainstay of treatment is systemic and includes chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted agents, used to improve quality of life. There is a strong relationship between response to chemotherapy and survival when compared to best supportive care [119, 120]. Additionally, palliative chemotherapy has been associated with improvements in several components of symptom relief and quality of life measures [121–123]. Having said this, continuing chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC until very near death is associated with a decreased likelihood of receiving hospice care but not prolonged survival [124]. Beyond three courses of chemotherapy conveys no survival or consistent quality of life benefits in advanced NSCLC patients [125]. Oncologists should strive to discontinue chemotherapy as death approaches and encourage patients to enroll in hospice for better end of life palliative care.

Considering this evidence, involvement of palliative care specialists is warranted, given the added mental, emotional, psychosocial, and medical complexity of care at this stage of disease. Importantly, involvement of palliative care specialists is beneficial to find the appropriate timing of transition to hospice care, which is often accomplished too late in the current model of care. In this one study, patients with metastatic NSCLC who received early palliative care measures still received similar number of chemotherapy regimens, but the timing of final chemotherapy administration and transition to hospice services were optimized [126].

Special considerations

Lung cancer in geriatric populations

The age at diagnosis for lung cancer is most often >70 years old, and oncologists are becoming increasingly aware of this expanding aged cancer population who face unique physical, psychological, and social challenges when receiving care. However, it is also becoming acutely apparent that similar to younger patients, carefully selected elderly patients can benefit from therapy at all stages of disease, and should not be excluded or under treated on the basis of age alone [127–131].

There is no significant difference in response or toxicity between younger and elderly patients receiving palliative radiation therapy [132]. Furthermore, preliminary studies show that higher doses of radiation are safe, effective, and may affect survival in aged NSCLC patients [133]. The previous fear that chemotherapy would be particularly toxic and harmful to elderly patients has also been quelled [134]. As with any age, consideration of comorbid conditions and risk factors should be weighed but elderly patients should not be excluded from this option [135]. Even patients with poor prognostic factors still exhibit positive response and symptom relief with palliative chemotherapy [136, 137]. Palliative surgical treatments too are being considered more readily in the elderly given similar benefits and quality of life expectations [138, 139]. As with other age groups, geriatric populations want to be involved in the decision-making process.

Family and caregiver support

Caregivers experience high levels of caregiver burden and reported deterioration in psychological well-being and overall quality of life [140, 141]. Distress and anxiety are understudied but accepted as widely prevalent among patients and their family caregivers. Several common areas of anxiety and distress exist, with the most prevalent themes emerging as uncertainty, loss or impending loss, changing roles, conflict outside, finances, physical symptoms, fears of decline and dying, and life after the patients’ passing [142].

A large area of distress stems from caregiver management of patient symptoms. There may be a discrepancy in how lung cancer patients and their caregivers assess and address both psychological and physical symptom occurrence and distress [143, 144]. Patient and caregiver self-efficacy and congruence of self-efficacy for managing pain, symptoms, and function affect several factors of distress and overall quality of life [145–147].

When given supportive services, both patients and caregivers have shown improvements in various parameters including pain, depression, self-efficacy, anxiety, and overall quality of life [148]. Thus, palliative care interventions aimed at caregiver and patient education, training, and support should be implemented early and consistently. Supportive efforts should be continued through treatment into the survivorship phase, and/or into the bereavement phase.

Advance care planning and transitions in care

Advance care planning (ACP) is a central component of palliative care. It includes both the medical aspect of care involving discussions with patients and families regarding goals of care, and the legal aspect of care involving the completion of either an advance directive form or a POLST. Presently, there are poor completion rates for ACP [149]. Despite overwhelming evidence that involvement of palliative services and hospice improve quality of care [150–152], poor utilization remains [153]. The goal would be to engage specialist palliative care teams earlier in a patient’s illness trajectory in order to maximally utilize resources while prioritizing shared decision-making and patient values.

Limitations

Research using quality of life parameters as outcome measures is becoming more accepted and widespread. However, most studies evaluating palliative measures in NSCLC have thus far been small and with mixed results. Research needs to be reproduced and replicated in order to validate a standardized approach to comprehensive cancer care for patients with NSCLC that integrates palliative care as a mechanism for ensuring optimal quality of life at any stage of disease experience (Fig. 1).

Conclusions

Palliative care is a specialized field that aims to provide effective symptom management and to maximize quality of life for patients and their caregivers through the entirety of illness trajectory from diagnosis to survivorship and end of life. Utilizing the care pathways as described in this article allow for personalized screening, assessment, and consistent implementation of palliative care interventions for patients and their families.

Initial treatment plan for all patients, regardless of stage, should encompass early assessment of clinical domains including physical symptoms, psychosocial distress, spiritual distress, and caregiver distress. Subsequent implementation of interventions and specialist referrals should be made based off needs of patients and caregivers.

In early-stage disease, the focus is primarily on surgical risk assessment and modification with particular attention paid to nutritional interventions and implementation of exercise training programs. It is essential that in post-therapy, there is utilization of a survivorship team to assist with treatment sequelae. In locally advanced disease, specific attention should be paid to coordination of care in addition to managing the physical ramifications of complex treatments such as concurrent chemotherapy and radiation and/or complex surgery. In the advanced stage of disease, relief of symptoms and optimization of care that is in alignment with patient and family goals is paramount. Additionally, understanding when a systemic treatment is appropriate for palliation and longevity versus when it may be contributing to hastening end of life is important. At this stage, it is recommended to add a specialist palliative care team to assist with ACP and transition to hospice. Palliative care is an expansive and innovative field that has the potential to revolutionize patient care.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance, •• Of major importance

Statistics for Different Kinds of Cancer. Cancer Prevention and Control 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/types.htm. Accessed 10 Dec 2015.

General Information About Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment –for health professionals (PDQ®). Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/non-small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq. Accessed 10 Dec 2015.

Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–9.

Temel JS, Greer JH, Muzikansky A, Gallagher EA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42. The authors randomly assign patients with newly diagnosed metastatic NSCLC to either receive early palliative care integrated with standard oncologic care or standard oncologic care. The hypothesis tested was that early palliative care would be beneficial concerning patient-reported outcomes and end of life care. They found that their hypothesis is strongly supported as patients who received early palliative care integrated with standard oncologic care showed higher scores on the FACT-L quality of life assessment instrument and fewer depressive symptoms. Interestingly, the early palliative care group patients also had less aggressive end of life care but longer survival.

Janssens A, Teugels L, van Meerbeeck JP. End of life care in lung cancer patients: not at life’s end? Ann Palliat Med. 2013;2(4):167–9. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2013.09.03.

Ostgathe C, Walshe R, Wolf J, Hallek M, Voltz R. A cost calculation model for specialist palliative care for patients with non-small cell lung cancer in a tertiary centre. Support Care Cancer. 2007;16(5):501–6.

Coy P, Schaafsma J, Schofield JA. The cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of high-dose palliative radiotherapy for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(4):1025–33.

Billingham L, Bathers S, Burton A, Bryan S, Cullen M. Patterns, costs and cost-effectiveness of care in a trial of chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;37(2):219–25.

Dooms C. Cost-utility analysis of chemotherapy in symptomatic advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2006.

Cooley ME. Symptoms in adults with lung cancer: a systematic research review. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2000;19(2):137–53.

LeBlanc TW, Nickolich M, Rushing CN, Samsa GP, Locke SC, Abernethy Su AP. What bothers lung cancer patients the most? A prospective, longitudinal electronic patient-reported outcomes study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3455–63. The authors and researchers at Duke University in North Carolina assessed patients with advanced NSCLC longitudinally over time using an electronic assessment instrument measuring patient-reported symptoms in order to gain more information regarding which symptoms occurred with what frequency and severity. The results showed that functional concerns predominated over non-functional concerns. Severe dyspnea and fatigue were the most prevalent nonfunctional symptoms. Depression was reported but infrequently. The number of moderate to severe symptoms increased with proximity to death. Overall, patients exhibited significant symptom burden which increased in frequency and severity closer to time of death.

Iyer S, Roughley A, Rider A, Taylor-Stokes G. The symptom burden of non-small cell lung cancer in the USA: a real-world cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:181–7.

Temel JS, Pirl WF, Lynch TJ. Comprehensive symptom management in patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7(4):241–9.

Granger CL, Denehy L, McDonald CF, Irving L, Clark RA. Physical activity measured using global positioning system tracking in non–small cell lung cancer: an observational study. Integr Cancer Ther 13(6):482–492.

Arbane G, Tropmanb D, Jackson J, Garrod R. Evaluation of an early exercise intervention after thoracotomy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), effects on quality of life, muscle strength and exercise tolerance: randomised controlled trial. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:229–34.

Quist M, Rorth M, Langer S, Jones LW, et al. Safety and feasibility of a combined exercise intervention for inoperable lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a pilot study. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:203–8.

Payne C, Larkin PJ, McIlfatrick S, Dunwoody L, Gracey JH. Exercise and nutrition interventions in advanced lung cancer: a systematic review. Curr Oncol. 2013;20(4):321–37. In this systematic review, the authors evaluated the effects of physical activity and nutrition interventions (or both) on adults with NSCLC. The results of the study support that exercise and nutrition interventions are not harmful and may be beneficial on unintentional weight loss, physical strength, and functional performance in NSCLC patients.

Kuehr L, Wiskemann J, Abel U, Ulrich CM, Hummler S, Thomas M. Exercise in patients with non–small cell lung cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014:656–663.

Granger CL, McDonald CF, Berney S, Chao C, Denehy L. Exercise intervention to improve exercise capacity and health related quality of life for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:139–53.

Cavalheri V, Tahirah F, Nonoyama ML, Jenkins S, Hill K. Exercise training undertaken by people within 12 months of lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer (review). The Cochrane Collaboration 2013. Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com. Accessed 14 Dec 2015.

Hoffman AJ, Brintnall RA, Eye AV, et al. Home-based exercise: promising rehabilitation for symptom relief, improved functional status and quality of life for post-surgical lung cancer patients. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(6):632–40.

Jones LW, Eves ND, Peterson BL, et al. Safety and feasibility of aerobic training on cardiopulmonary function and quality of life in postsurgical nonsmall cell lung cancer patients. Available at: www.interscience.wiley.com. Accessed 12 Dec 2015.

Hoffman AJ, Brintnall RA, Brown JK, et al. Too sick not to exercise: using a 6-week, home-based exercise intervention for cancer-related fatigue self-management for postsurgical non small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(3):175–88.

Sanchez-Lara K, Arrieta O, Pasaye E, et al. Brain activity correlated with food preferences: a functional study comparing advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients with and without anorexia. Nutrition. 2013;29:1013–9.

Tisdale MJ. Mechanisms of cancer cachexia. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:381–410.

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;2:489–95.

Fearon KC, Voss AC, Hustead DS, Cancer Cachexia Study G. Definition of cancer cachexia: effect of weight loss, reduced food intake, and systemic inflammation on functional status and prognosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6):1345–50.

Petrella F, Radice D, Borri A, et al. The impact of preoperative body mass index on respiratory complications after pneumonectomy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Results from a series of 154 consecutive standard pneumonectomies. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:738–44.

Tewari NI, Martin-Ucar AE, Black E, et al. Nutritional status affects long term survival after lobectomy for lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:389–94.

Jagoe RT, Goodship TH, Gibson GJ. The influence of nutritional status on complications after operations for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:936–43.

Ross PJ, Ashley S, Norton A, Priest K, Waters JS, Eisen T, et al. Do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancers? Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1905–11.

Arrieta O, Michel Ortega RM, Villanueva-Rodríguez G, Serna- Thoméh MG, Flores-Estrada D, Diaz-Romero C, et al. Association of nutritional status and serum albumin levels with development of toxicity in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with paclitaxel–cisplatin chemotherapy: a prospective study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:50.

Op Den Kamp CMH, De Ruysscher DKM, Heuvel MVD, et al. Early body weight loss during concurrent chemo-radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer. J Cachex Sacropenia Muscle. 2014;5:127–37.

Kimura M, Naito T, Kenmotsu H, Taira T, Wakuda K, et al. Prognostic impact of cancer cachexia in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1699–708.

Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS, Reiman T, Mazurak VC. Skeletal muscle depletion is associated with reduced plasma (n-3) fatty acids in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Nutr. 2010;140:1602–6.

van der Meij BS, Languis JAE, Spreeuwenberg MD, et al. Oral nutritional supplements containing n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids affect quality of life and functional status in lung cancer patients during multimodality treatment: an RCT. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:399–404.

van der Meij BS, Languis JAE, Smit EF, et al. Oral nutritional supplements containing (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids affect the nutritional status of patients with stage III non-small cell lung cancer during multimodality treatment. Available at: jn.nutrition.org.

Del Ferraro C, Grant M, Koczywas M, Dorr-Uyemura LA. Management of anorexia-cachexia in late-stage lung cancer patients. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2012;14:397–402.

Granda-Cameron C, Demille D, Lynch MP, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to manage cancer cachexia. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(1):72–80.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9.

LeBlanc TW, Samsa GP, Wolf SP, Locke SC, Cella DF, Abernethy AP. Validation and real-world assessment of the functional assessment of anorexia–cachexia therapy (FAACT) scale in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and the cancer anorexia–cachexia syndrome (CACS). Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:2341–7.

Salsman JM, Beaumont JL, Wortman K, Yan Y, Friend J, Cella D. Brief versions of the FACIT-fatigue and FAACT subscales for patients with non-small cell lung cancer cachexia. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1355–64.

Potter J, Higginson IJ. Pain experienced by lung cancer patients: a review of prevalence, causes and pathophysiology. Lung Cancer. 2004;43:247–57.

Caraceni A, Portenoy RK. An international survey of cancer pain characteristics and syndromes. IASP Task Force on Cancer Pain. Pain. 1999;82(32):263–74.

Portenoy RK. Treatment of cancer pain. Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2236–47.

Chute CG, Greenberg ER, Baron J, Korson R, Baker J, Yates J. Presenting conditions of 1539 population-based lung cancer patients by cell type and stage in New Hampshire and Vermont. Cancer. 1985;56(8):2107–11.

Simmons et al. Clinical management of pain in advanced lung cancer. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2012; 6: 331–346. URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3474460/.

Mercandante S, Vitrano V. Pain in patients with lung cancer: pathophysiology and treatment. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:10–5.

Geneva W. Cancer pain relief. World Health Organisation; 1996.

Ferrel B, Levy MH, Paice J. Managing pain from advanced cancer in the palliative care setting. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:575–81.

Yuan CS. Methylnaltrexone mechanisms of action and effects on opioid bowel dysfunction and other opioid adverse effects. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(6):984–93.

Hu M, Zhi X, Zhang J. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for palliative treatment of painful non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) rib metastasis: experience in 12 patients. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6:761–4.

Barbera L, Zhang-Salomons J, Huang J, Tyldesley S, Mackillop W. Defining the need for radiotherapy for lung cancer in the general population: a criterion-based, benchmarking approach. Med Care. 2003;41(9):1074–85.

Toy E, Macbeth F, Coles B, Melville A, Eastwood A. Palliative thoracic radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26(2):112–20.

Cassileth BR, Deng GE, Gomez JE, Johnstone PA, Kumar N, Vickers AJ. Complementary therapies and integrative oncology in lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest. 2007;132 Suppl 3:340S–54.

Molassiotis A, Lowe M, Blackhall F, Lorigan P. A qualitative exploration of a respiratory distress symptom cluster in lung cancer: cough, breathlessness and fatigue. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:94–71:9.

Cheville AL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, et al. The value of a symptom cluster of fatigue, dyspnea, and cough in predicting clinical outcomes in lung cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;42(2):213.

Tiep et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation and palliative care for the lung cancer patient. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2015;17(5):462–8.

Cheville AL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, et al. Fatigue, dyspnea, and cough comprise a persistent symptom cluster up to five years after diagnosis with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:202–12.

Henoch I, Bergman B, Gustaffson M, Gaston-Johansson F, Danielson E. Dyspnea experience in patients with lung cancer in palliative care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:86–12.

Koczywas et al. Interdisciplinary palliative care intervention in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14(6):736–44.

Henoch I, Bergman B, Danielson E. Dyspnea experience and management strategies in patients with lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17(7):709–15.

Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131 suppl 5:4S–2.

Abernethy AP, McDonald CF, Frith PA, et al. Effect of palliative oxygen versus room air in relief of breathlessness in patients with refractory dyspnoea: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9743):784–93.

Tiep B, Carter R, Zachariah F, et al. Oxygen for end-of-life lung cancer care: managing dyspnea and hypoxemia. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2013;7(5):479–90.

Currow DC, Ekstrom M, Abernethy AP. Opioids for chronic refractory breathlessness: right patient, right route? Drugs. 2014;74(1):1–6.

Yates et al. Supportive and palliative care for lung cancer patients. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(5):S623–8. This review study evaluated evidence-based interventions that support best practice supportive and palliative care for patients with lung cancer, specifically interventions to manage dyspnea and psychosocial interventions to reduce anxiety and distress.

Rueda JR, Solà I, Pascual A, Subirana Casacuberta M. Non-invasive interventions for improving well-being and quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9, CD004282.

Henoch I, Bergman B, Gustafsson M, Gaston-Johansson F, Danielson E. The impact of symptoms, coping capacity, and social support on quality of life experience over time in patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;34(4):370–9.

Akechi T, Okuyama T, Akizuki N, et al. Course of psychological distress and its predictors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Available at: www.interscience.wiley.com. Accessed 12 Jan 2016.

Murray SA, Kendall M, Grant E, Boyd K, Barclay S, Sheikh A. Patterns of social, psychological, and spiritual decline toward the end of life in lung cancer and heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;34(4):393–402.

Hopwood P, Stephens RJ. Depression in patients with lung cancer: prevalence and risk factors derived from quality of life data. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):893–903.

Carlsen K, Jensen AB, Jacobsen E, Krasnik M, Johansen C. Psychosocial aspects of lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2005;47:293–300.

Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Predictors of depressive symptomatology of geriatric patients with lung cancer—–a longitudinal analysis. Psychooncology. 2002;11:12–22.

Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(12):1310–5.

Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1797–810.

Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:5349–61.

Fujisawa D, Temel JS, Traeger L, et al. Psychological factors at early stage of treatment as predictors of receiving chemotherapy at the end of life. Available at: wileyonlinelibrary.com. Accessed 10 Dec 2015.

Akechi T, Kugaya A, Okamura H, Nishiwaki Y, Yamawaki S, Uchitomi Y. Predictive factors for psychological distress in ambulatory lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6:281–6.

Prasertsri N, Holden J, Keefe FJ, Wilkie DJ. Repressive coping style: relationships with depression, pain, and pain coping strategies in lung cancer out patients repressive coping style: relationships with depression, pain, and pain coping strategies in lung cancer out patients. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:235–40.

Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, Kirsh KL, Moore PG, Passik SD. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:215–24.

Jamal A, Homa DM, O’Connor E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults — United States, 2005–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(44):1233–40.

Nia PS, Weyler J, Colpaert C, Vermeulen P, Marck EV, Schil PV. Prognostic value of smoking status in operated non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2005;47:351–9.

Liu X, Lin XJ, Wang CP, et al. Association between smoking and p53 mutation in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Oncol. 2014;26:18–24.

Tam IY, Chung LP, Suen WS, Wang E, Wong MC, Ho KK, et al. Distinct epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS mutation patterns in non-small cell lung cancer patients with different tobacco exposure and clinicopathologic features. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1647–53.

Togashi Y, Hayashi H, Okamoto K, Fumita S, Terashima M, et al. Chronic nicotine exposure mediates resistance to EGFR-TKI inEGFR-mutated lung cancer via an EGFR signal. Lung Cancer. 2015;88:16–23.

Zhai R, Yu X, Su L, Christiani DC. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to the development of co-existing non-small cell lung cancer with chronicobstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:961–70.

Boyle JM, Tandberg DJ, Chino JP, D’Amico TA, Ready NE, Kelsey CR. Smoking history predicts for increased risk of second primary lung cancer: a comprehensive analysis. Available at: wileyonlinelibrary.com. Accessed 12 Jan 2016.

Zhou W, Heist RS, Liu G, Zhai R, Yu X, Su L, et al. Smoking and smoking cessation in relation to the development of co-existing non-small cell lung cancer with chronicobstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:961–70. Lung Cancer 2006;53:375–380.

Baser S, Shannon VR, Eapen GA, et al. Smoking cessation after diagnosis of lung cancer is associated with a beneficial effect on performance status. Chest. 2006;130(6):1784–90.

Rennard SI, Daughton DM. Smoking cessation. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):165–76.

Koplan KE, David SP, Rigotti NA. Smoking cessation. BMJ. 2008;336(7637):217.

Srivastava P. Smoking cessation. BMJ. 2006;332(7553):1324–6.

Sun V, Kim JY, Irish TL, et al. Palliative care and spiritual well-being in lung cancer patients and family caregivers. Available at: wileyonlinelibrary.com. Accessed 2015.

Lovgren M, Tishelman C, Sprangers M, Koyi H, Hamberg K. Symptoms and problems with functioning among women and men with inoperable lung cancer—–a longitudinal study. Lung Cancer. 2008;60:113–24.

Jacobs-Lawson JM, Schumacher MM, Hughes T, Arnold S. Gender differences in psychosocial responses to lung cancer. Gend Med. 2010;7(2):137–48.

Borneman T. Spiritual assessment in a patient with lung cancer. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2014;5(6):448–53.

Non-small cell lung cancer survival rates, by stage. Non Small Cell Lung Cancer 2014. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/lungcancer-non-smallcell/detailedguide/non-small-cell-lung-cancer-survival-rates. Accessed 10 Dec 2015.

Hung R, Krebs P, Coups EJ, et al. Fatigue and functional impairment in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer survivors. C22. Behavioral And Psychosocial Factors In Asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease And Other Lung Diseases 2010.

Krebs P, Coups EJ, Feinstein MB, et al. Health behaviors of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;6(1):37–44.

Fouladbakhsh JM, Davis JE, Yarandi HN. A pilot study of the feasibility and outcomes of yoga for lung cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(2):162–74.

Peddle-Mcintyre CJ, Bell G, Fenton D, Mccargar L, Courneya KS. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of progressive resistance exercise training in lung cancer survivors. Lung Cancer. 2012;75(1):126–32.

Ostroff JS, Krebs P, Coups EJ, et al. Health-related quality of life among early-stage, non-small cell, lung cancer survivors. Lung Cancer. 2011;71(1):103–8.

Vijayvergia N, Shah PC, Denlinger CS. Survivorship in non-small cell lung cancer: challenges faced and steps forward. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2015;13(9):1151–61. In this study, the authors summarize the major issues faced by NSCLC survivors and suggest appropriate management. Most NSCLC carry a higher comorbidity burden than survivors of other cancers and overall quality of life and health-related quality of life decrease. Symptoms including respiratory issues, fatigue, hearing loss, neuropathy, post-surgical pain, psychological distress, depression, financial issues, poor compliance with recommended guidelines, and fear of recurrence or secondary malignancies are common and burdensome among survivors.

Colt HG, Murgu SD, Korst RJ, Slatore CG, Unger M, Quadrelli S. Follow-up and surveillance of the patient with lung cancer after curative-intent therapy. Chest. 2013;143(5).

Lou F, Huang J, Sima CS, Dycoco J, Rusch V, Bach PB. Patterns of recurrence and second primary lung cancer in early-stage lung cancer survivors followed with routine computed tomography surveillance. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145(1):75–82.

Mollberg NM, Ferguson MK. Postoperative surveillance for non-small cell lung cancer resected with curative intent: developing a patient-centered approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(3):1112–21.

Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144(1):33–8.

Ocana CV, Lopez PG, Trueba IM. Multidisciplinary approach in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: standard of care and open questions. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13:629–35.

Boxer MM, Vinod SK, Shafiq J, Duggan KJ. Do multidisciplinary team meetings make a difference in the management of lung cancer? Cancer 2011:5112–5120.

Howe M, Burkes RL. Collaborative care in NSCLC; the role of early palliative care. Front Oncol. 2014;4:1–3.

Temel JS, Jackson VA, Billings JA, et al. Phase II study: integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2377–82.

Ferrel B, Sun V, Hurria A, et al. Interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015:1–10. In this study, patients with stage IV NSCLC were enrolled in a prospective quasi-experimental study where the intervention group was presented at interdisciplinary care meetings where appropriate supportive care referrals were made. The authors hypothesized that interdisciplinary care would be beneficial which the results strongly supported, showing significant improvement in quality of life, symptoms and distress.

Ramella S, D’Angelillo RM. Radiotherapy in palliative treatment of metastatic NSCLC: not all one and the same. Ann Palliat Med. 2013;2(2):92–4.

Langendijk JA, Aaronson NK, ten Velde GPM, Jong JMA, Muller MJ, Wouters EFM. Pretreatment quality of life of inoperable non-small cell lung cancer patients referred for primary radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2000;39(8):949–58.

Langendijk JA, ten Velde GPM, Aaronson NK, de Jong JM, Muller MJ, Wouters EFM. Quality of life after palliative radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2000;47(1):149–55.

Langendijk JS, Aaronson NK, de Jong JM, et al. Prospective study on quality of life before and after radical radiotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(8):2123–33.

Schaafsma J, Coy P. Response of global quality of life to high-dose palliative radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2000;47(3):691–701.

Klastersky J, Paesmans M. Response to chemotherapy, quality of life benefits and survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: review of literature results. Lung Cancer. 2001;34:S95–101.

Chemotherapy and supportive care versus supportive care alone for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (Review). Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com.

Belani CP, Pereira JR, Jvon, et al. Effect of chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer on patients’ quality of life. A randomized controlled trial. Lung Cancer. 2006;53:231–9.

Mannion E, Gilmartin JJ, Donnellan P, Keane M, Waldron D. Effect of chemotherapy on quality of life in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1417–28.

Matsudo A, Yamaoka K, Tango T. Quality of life in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving palliative chemotherapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Exp Therapeut Med. 2012;3:134–40.

Saito AM, Landrum MB, Neville BA, Ayanjan JZ, Earle CC. The effect on survival of continuing chemotherapy to near death. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10(14):1–11.

Plessen C, Bergman B, Andersen O, et al. Palliative chemotherapy beyond three courses conveys no survival or consistent quality-of-life benefits in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:966–73.

Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;30:394–400.

Ng R, de Boer R, Green MD. Undertreatment of elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2005;7(3):168–74.

Berghmans T, Tragas G, Sculier JP. Age and treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: a database analysis in elderly patients. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:619–23.

Weiss J, Langer C. NSCLC in the elderly—the legacy of therapeutic neglect. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2009;10:180–94.

Aggarwal C, Langer CJ. Older age, poor performance status and major comorbidities: how to treat high-risk patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24(2):130–6.

Domingues PM, Zylberberg R, da Matta de Castro T, Baldotto CS, de Lima Araujo LH. Survival data in elderly patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:1–6.

Turner NJ, Muers MF, Haward RA, Mulley GP. Do elderly people with lung cancer benefit from palliative radiotherapy? Lung Cancer. 2005;49:193–202.

Lonardi F, Coeli M, Pavanato G, Adami F, Gioga G, Campostrini F. Radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer in patients aged 75 and over: safety, effectiveness and possible impact on survival. Lung Cancer. 2000;28:43–50.

Costa GJ, Fernandes ALG, Pereira JR, Curtis JR, Santoro IL. Survival rates and tolerability of platinum-based chemotherapy regimens for elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer. 2006;53(2):171–6.

Santos FN, Castria TBD, Cruz MR, Riera R. Chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly population. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015.

Hickish T, Smith I, O’brien M, Ashley S, Middleton G. Clinical benefit from palliative chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer extends to the elderly and those with poor prognostic factors. Br J Cancer. 1998;78(1):28–33.

Earle CC, Tsai JS, Gelber RD, Weinstein MC, Neumann PJ, Weeks JC. Effectiveness of chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer in the elderly: instrumental variable and propensity analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(4):1064–70.

Ferguson MK, Parma CM, Celauro AD, Vigneswaran WT. Quality of life and mood in older patients after major lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1007–13.

Burfeind WR, Tong BC, O’branski E, et al. Quality of life outcomes are equivalent after lobectomy in the elderly. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136(3):597–604.

Grant M, Sun V, Fujinami R, et al. Family caregiver burden, skills preparedness, and quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(4):337–46.

Gridelli C, Ferrara C, Guerriero C, et al. Informal caregiving burden in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the HABIT study. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(6):475–80.

Hendriksen E, Williams E, Sporn N, Greer J, Degrange A, Koopman C. Worried together: a qualitative study of shared anxiety in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2014;23(4):1035–41.

Broberger E, Tishelman C, Essen LV. Discrepancies and similarities in how patients with lung cancer and their professional and family caregivers assess symptom occurrence and symptom distress. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;29(6):572–83.

Mcpherson CJ, Wilson KG, Lobchuk MM, Brajtman S. Family caregivers’ assessment of symptoms in patients with advanced cancer: concordance with patients and factors affecting accuracy. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2008;35(1):70–82.

Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, Mcbride CM, Baucom D. Self-efficacy for managing pain, symptoms, and function in patients with lung cancer and their informal caregivers: associations with symptoms and distress. Pain. 2008;137(2):306–15.

Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Porter LS, et al. The self-efficacy of family caregivers for helping cancer patients manage pain at end-of-life. Pain. 2003;103(1):157–62.

Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Mcbride CM, Pollak K, Fish L, Garst J. Perceptions of patientsʼ self-efficacy for managing pain and lung cancer symptoms: correspondence between patients and family caregivers. Pain. 2002;98(1):169–78.

Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, et al. Caregiver-assisted coping skills training for lung cancer: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41(1):1–13.

Mccarthy EP. Hospice use among Medicare managed care and fee-for-service patients dying with cancer. JAMA. 2003;289(17):2238.

Obermeyer Z, Clarke AC, Makar M, Schuur JD, Cutler DM. Emergency care use and the Medicare hospice benefit for individuals with cancer with a poor prognosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016.

Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888.

Zuckerman RB, Stearns SC, Sheingold SH. Hospice use, hospitalization, and medicare spending at the end of life. GERONB J Gerontol Ser B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015.

Benson WF, Aldrich N. Advance care planning: ensuring your wishes are known and honored if you are unable to speak for yourself, critical issue brief, centers for disease control and prevention. 2012. www.cdc.gov/aging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Lung Cancer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chandrasekar, D., Tribett, E. & Ramchandran, K. Integrated Palliative Care and Oncologic Care in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options in Oncol. 17, 23 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-016-0397-1

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-016-0397-1