Abstract

The likelihood of success of a marine protected area (MPA) is strongly dependent on stakeholders’ support. A concern often raised by local fishers is their lack of involvement in the design or management of a MPA and their loss of income owing to lost fishing grounds. We used Algoa Bay, South Africa, as a case study to analyse fisher’s and fish-processing factory managers’ concerns and perceived economic losses from fishing closures using structured interviews. Since 2009, a 20 km-radius purse-seine fishing-exclusion zone has been tested in Algoa Bay to assess the benefit to population recovery of the endangered African penguin Spheniscus demersus. Costs to the industry were estimated in terms of loss of catches and additional travel time to fishing grounds with and without closures. Fisher responses to interviews revealed general support for conservation and MPAs, but individuals interviewed did not feel that the 20 km fishing exclusion zones in Algoa Bay would aid African penguin conservation. While they systematically raised concerns about potential economic costs to their industry from closures, neither their catch sizes nor travel times varied significantly with fishing exclusion measures. Acknowledgement and assessment of the economic concerns may aid in initiating an informed dialogue amongst the various stakeholders in Algoa Bay, which may increase compliance and success of the newly proclaimed Addo elephant National Park MPA. Continued dialogue may also act as a catalyst for more integrated ocean management of biodiversity and human uses in the bay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As the number of threatened marine species increases (Worm et al. 2013; McCauley et al. 2015), urgent action is required to assess and limit anthropogenic drivers of species’ declines and prevent extinctions (Davidson and Dulvy 2017; Duarte et al. 2020). Fully-protected and well-managed marine protected areas (MPAs) can provide a refuge for species and ecosystems (Grorud-Colvert et al. 2021; Roberts et al. 2017) and can contribute to food security and carbon storage (Sala et al. 2021). In the absence of MPAs, fishing-exclusion zones can protect harvested species and support ecosystem-based management of coastal and marine environments (Sardá et al. 2017). Historically, MPAs and other spatial conservation measures (such as fishing-exclusion zones) have been implemented to improve the conservation status of ecological system components (such as species or habitats), with less attention paid to the socio-economic costs of the intervention (Dehens and Fanning 2018; Brander et al. 2020, although see Smith et al. 2010). Prior analyses of MPAs have identified stakeholder engagement as a major factor in influencing the success or failure of an MPA (Giakoumia et al. 2018), and South Africa is no exception (Mann-Lang et al. 2021).

In 2014, the South African government initiated Operation Phakisa, an initiative to develop the South African oceans economy by growing various ocean-based industry sectors, including offshore oil and gas exploration, fisheries and aquaculture, marine transport and manufacturing, and marine protection. Four years later, the 2018 National Biodiversity Assessment for South Africa identified commercial fishing as a major threat to marine biodiversity and ecosystems in South Africa, owing to overexploitation of target species, high bycatch rates, habitat destruction, and competition for food resources with other marine species, as well as incidental seabird deaths (Majiedt et al. 2019). In 2019, twenty new MPAs were approved by the South African cabinet as part of Operation Phakisa. One of the new MPAs is the Addo Elephant National Park MPA located in Algoa Bay (Fig. 1) on the south coast of South Africa with a primary objective to protect the habitats of two Endangered seabird species: the African penguin Spheniscus demersus and the Cape gannet Morus capensis breeding on St Croix and Bird Islands (SANBI and South African Department of Environmental Affairs, 2018). Algoa Bay used to host 50% and 70% of the world African penguin and Cape gannet populations respectively on St Croix and Bird islands (Sherley et al. 2019, 2020, Fig. 1). Both species are endemic to Southern Africa and feed primarily on sardine (also referred to as pilchard) Sardinops sagax and anchovy Engraulis encrasicolus (Crawford 2007), which are targeted by the purse-seine fishery. This fishery contributes to the highest tonnage landed by fisheries in South Africa (Shannon and Waller 2021), with annual tonnage averaging around 391 000 tons between 2008 and 2012, including catches of sardine, anchovy, horse mackerel Trachurus trachurus and round herring Spratelloides gracilis (Wilkinson and Japp 2018). Catches from Algoa Bay represented 40 to 70% of national landings of sardines during our study (Coetzee et al. 2019), and are used primarily for the bait industry. Given the potential conflict for food resources, the competition between seabird species and the commercial fishing industry have been the focus of ongoing studies (Crawford 2007; Pichegru et al. 2009, 2010, 2012; McInnes et al. 2017; Sherley et al. 2018). For example, spatial analyses revealed that a significant proportion of the catches from the purse-seine fishing is located in the core foraging habitats of penguins and gannets (Pichegru et al. 2009).

Map of study area, showing the seabird colonies (St Croix and Bird islands) in Algoa Bay, the Addo Elephant National Park Marine Protected Area zonation (controlled and restricted, and the 20 km radius experimental purse-seine fishing exclusion zones around the islands, including 5 km around Ryi Bank. The map also shows (surrounded in black) the extent of the ‘Algoa Bay’ area where fishing catches and travel times were considered in this study (following Pichegru et al. 2012)

As early as 2009, as part of a national experiment designed by a group of stakeholders including scientists and the fishing industry, 20 km experimental purse-seine fishing-exclusion zones were implemented around key penguin colonies in Algoa Bay (around St Croix and Bird Islands), and on the West Coast of South Africa (around Dassen and Robben Islands, to assess the potential benefits of exclusion zones for African penguins (see Pichegru et al. 2010, 2012; Sherley et al. 2018; Sydeman et al. 2021). Part of the experimental design involved swapping the fishing exclusion every three years within pairs of colonies: in Algoa Bay, the area surrounding St Croix Island was closed to fishing from 2009 to 2011, and again in 2015–2017, while allowed around Bird Island. Bird Island area was closed to fishing 2012–2014, and again from 2018 onward. Various parameters of African penguins’ responses to changes in the fishing exclusion regime were monitored (see Pichegru et al. 2012; Sherley et al. 2018). Historical fishing pressure was much higher around St Croix Island than Bird Island, due to St Croix’s proximity to the harbour (Pichegru et al. 2012), thus penguins from St Croix rapidly restricted their foraging range to mostly within the fishing-exclusion zone, reducing their energy expenditure during periods when the exclusion zone was in effect around that colony (Pichegru et al. 2010). However, evidence was provided that a larger fishing exclusion was needed in Algoa Bay to support the declining African penguin population and prevent the concentration of fishing activities at the exclusion zone boundary (i.e., ‘fishing the line’, Pichegru et al. 2012; Sherley et al. 2018).

The proclamation of the Addo Elephant National Park MPA in 2019 was a step towards potential improved penguin conservation, but the restricted zone of the MPA (where fishing is not permitted) offers poor coverage of foraging habitat for African penguins, especially those breeding on St Croix Island, and did not include most of the historical and current fishing grounds of the small pelagic industry (Pichegru et al. 2012). Nevertheless, commercial fishers who target small pelagic fish remain concerned about the loss of fishing grounds following any form of fishing exclusion, and fear decreases in catch and loss of income, especially in the light of possible additional exclusions to assist the recovery of African penguins. These concerns need to be addressed if more permanent and larger fishery exclusion zones to benefit penguins are to have any chance of success.

This research aimed to first understand the purse-seine fishers’ perceptions of fishing exclusion zones (be they temporary or implemented as zones in MPAs) and their perceived impacts of these measures on their fishery. We then compared these perceptions with estimates of the impacts of fishing exclusions on costs to the purse-seine fishing industry (i.e. decrease of catches, increase of travel times). Using structured interviews, we assessed local fisher’s views on marine top predator conservation status, the use of MPAs and the sustainability of fishing industries in general. In parallel, we quantified the effect that the fishing-exclusion zone around St Croix Island had on catch size and travel time of the local purse-seine fishery. This study is a first step towards reconciling conservation and fishery goals in area-based conservation measures for endangered marine top predators in Algoa Bay. It provides insights into stakeholders’ perceptions and how these may be addressed to promote the sustainability of both the fishery and the foraging needs of penguins, and to enable a more integrated ocean management approach that considers both biodiversity and human uses of the bay (Vermeulen et al. 2022).

Materials and methods

Structured interviews

Nine individuals were interviewed (structured interview in Supplementary material) for their opinions on fishing-exclusion zones. These interviews aimed to collect insights of pelagic fishers from a “realist perspective” (Crouch and McKenzie 2006), not relying on a large sample size of a subgroup (Daniel 2012). Through these interviews, we collected perceptions of a group with common interests and active in the pelagic fisheries in Algoa Bay. We used a snowball sampling (also known as purposive sampling), whereby an initial participant was identified and with their help, the interviewer was introduced to additional potential participants (Bernard 2017). Five individuals were fishers on purse-seine vessels operating from Port Elizabeth harbour and four were managers of factories (floor managers and operations managers) that process sardine in the city. While the sample size was small, it did represent most of the “top-tier” individuals in the small local purse-seine fishing community. Involvement in the study was voluntary, answers were kept anonymous, and participants were assigned a random number from 1 to 9. Interviews were conducted face-to-face and at various locations where the participants felt comfortable. Answers were scribed by the interviewer and no voice recording devices were used. Human ethics (H18-SCI-ZOO-004) approval was granted by the Nelson Mandela University human ethics committee.

The structured interviews consisted of three main themes: marine predators, fishery-exclusion zones (and MPAs more broadly), and the sustainability of the purse-seine fishery. The questions (see Supplementary material) were open-ended and designed to ensure that the questions flowed well, were phrased suitably, and did not lead participants to a particular response. An attempt was made to structure the interviews according to position in the fishery, and some questions when not applicable were omitted (e.g. PS5, PS6, PS7 for managers, see Suppl. Mat.). Responses of the participants were analysed in view of their position in the fishery, fishers (n = 5, four skippers and one first mate) or managers (n = 4), and age class: “younger” (age 18–40 years old, n = 3) and “older” (41 + years, n = 6).

Fishery exclusion and catches

Catch data of the Eastern Cape pelagic purse-seine fishery (2007–2017) were obtained from the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE). Data are reported by the fishing industry to the Department in tonnes of catches per species per trip for each vessel, with spatial coordinates of the area of the catch, as well as time of departure from and return to the harbour, and vessel ID. We quantified the effects of the exclusion zone around St Croix Island alone (in effect in 2009–2011 and then again in 2015–2017), given that the Bird Island area was seldom fished by purse-seiners (Pichegru et al. 2012; McInnes 2016) and St Croix Island was the closest to the Port Elizabeth harbour and the largest local African penguin breeding population at the time (Sherley et al. 2020). In this study, we considered catches in tonnes of small pelagic fish in Algoa Bay, as the area defined by Pichegru et al. (2012) (Fig. 1). While movement of fishing vessels to the neighbouring harbour of Cape St Francis (80 km west) can occur, most (> 80%) of the catches from the Eastern Cape small pelagic fishing industry take place in Algoa Bay, in relatively close proximity of the Port Elizabeth harbour (Pichegru et al. 2012).

The effect of the fishing-exclusion regime around St Croix Island was tested on catch sizes (as a proxy for revenue) and travel time (i.e., difference between vessel departure time from the port and arrival time back at port, as a proxy for costs both in terms of fuel costs and time spent searching for fish) for each fishing trip in Algoa Bay. A log transformation was used for travel time in order to improve the symmetry of the distribution of the variable to meet the assumption of normality. Exclusion regimes were designated as Open 1: 2007–2008, Closed 1: 2009–2011, Open 2: 2012–2014 and Closed 2: 2015–2017). Catch size or log travel time were set as the response variables in an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), with combinations of exclusion regime, year and vessel ID as explanatory factors. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were checked using residuals.

In addition, because vessels are limited by their hull capacity in the tonnage of fish they can catch per trip (ca. 40 tons for vessels in Algoa Bay, but vessels can do additional trips), effect of fishing exclusions was also tested on the total annual catch of the fishery with a one-way ANOVA, and a Tukey post-hoc test. Statistical tests were conducted in R 4.2.0 (R Core Team, 2022).

Results

Perception of fishers: marine life

Participants’ responses regarding interactions with marine life are presented in Table 1. Marine predators like sharks or seals can conflict with fishers when they intercept catches or damage equipment. Penguins were not considered a nuisance because they did not steal the catch. Predators could, however, be perceived in a good light as they can be used to locate productive fishing grounds.

Bycatch (catch of non-targeted species) had both positive and negative aspects according to the purse-seine fishers. Some bycatch species may provide supplemental income to fishers if it can be sold (e.g. mackerel Scomber scombrus), with this being especially important during periods of low targeted fish catch. Alternatively, bycatch of species such as barbels or sharks may damage nets or take up valuable space in the net and thus reduce income for fishers.

Opinions about the conservation status of marine predators and the sustainability of fishing world-wide are presented in Table 2. Opinions differed between age groups, with an apparent division among older individuals. Most participants felt that the loss of predators would negatively affect the environment because marine predators are “part of the ecosystem” and the “natural balance of the sea”. But when examining the differences in opinions based on job position or age, one older fisher stated that the loss of predators would allow for “more fish for the fishermen” while one older manager said that “the workings of the sea would balance things out”.

When asked about the sustainability of fishing world-wide and locally, all participants recognised that overfishing was a serious global threat (Table 3). However, when asked specifically about the sustainability of the purse-seine fishery, responses were more varied. Most managers viewed the fishery as unsustainable, while fishers were not in agreement. When discussing their fishing activity around Algoa Bay’s islands, all nine participants stated that the purse-seine fishing activity did not impact species present on Bird or St Croix Islands, explaining that the boats and nets used were “too small to have a large impact”, perhaps even “give easy meals to animals”.

Nevertheless, the majority of the participants agreed that top predators needed conservation measures. Interestingly, when discussing how to conserve marine predators, multiple methods were suggested, including “MPAs and more control of the fisheries” and “helping pelagic stock recovery”, “using research and educational programs for people in the fishing industry and get all role-players together”, as well as “identify what is causing the decline and control that”.

Perception of fishers: MPAs

Opinions regarding the impact of MPAs on the environment and the fishing industry are summarised in Table 4 They differed among the participants, with both positive and negative comments. Positive views of MPAs were predominantly about the environment as a whole, such as helping reefs or acting as a refuge for fish, or for certain species, like whales and dolphins or spawning sardines. However, very few positives for the fishery were listed by participants. Rather, all participants (except for one young fisher) felt that an MPA in Algoa Bay would threaten their jobs. The concern of increased fuel costs was voiced by three of the five fishers. Impact on catch size was voiced by a manager. Three participants mentioned the issue of lack of enforcement of the MPA.

Estimates of fishing exclusion impacts on fisheries’ economic cost

A total of 2007 purse-seine fishing trips took place in Algoa Bay between 2007 and 2017, 828 of these when the fishing exclusion was in place around St Croix Island and 1179 when it was not. The number of vessels operating in the region varied between years with a maximum of 14 boats operating per year. Boats differed in their hull capacity and catches, as well as travel times (Figure S1). Some vessels (N = 5) conducted only one or two fishing trips in the bay during our study period. Another seven vessels conducted between 11 and 34 trips, whereas eight conducted between 122 and 396 trips.

Average catches per trip were slightly higher when the exclusion was in place, with 25.33 ± 11.97 tonnes per trip, compared to 23.75 ± 12.22 tonnes when it was not. The results of the ANOVA showed a significant interaction effect between closure regime and vessel (F = 1.7; p = 0.033). This interaction effect is illustrated in Fig. 2a, showing how the different vessels showed a different response to the closure regimes. For example, vessels 499 and 506 had their largest catches during 2010 when the island was closed to fishing, while other vessel’s catches were lower during this period. A model including the interaction between vessel and year was not significant and hence the interaction was removed from the final model.

Average (± SD) of (a) catch size (tonnes) and (b) travel time (log transformed) of small pelagic fish per individual purse-seine fishing vessels operating in Algoa Bay between 2007 and 2017. Shaded areas represent years with a fishing exclusion around St Croix Island, Algoa Bay, South Africa. Note: no fishing took place in Algoa Bay in 2015

Similarly, average (± SD) travel time of fishing trips in Algoa Bay tended to be slightly lower when the St Croix fishing-exclusion zone was in effect (11.15 ± 5.71 h) than when it was not (11.33 ± 5.45 h) (Fig. 2b). The results of the ANOVA for the travel time showed a significant interaction effect between closure regime and boat \((F=5.00;p<0.001)\), as well as between boat and year \((F=1.66;p=0.011)\). Again, different vessels experienced different responses to the closure regime, with some vessels (e.g., 499 and 485) having their longest travel times in 2014 when the island area was open to fishing.

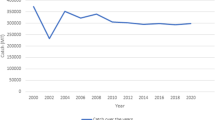

However, the overall annual catches by the industry in the area decreased over time, regardless of the fishing exclusion regime (Fig. 3 and Figure S2), and the one-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in annual total catch during open and closed periods overall \(\left(F=1.174, p=0.307\right).\)However, if the four levels of the closure regime were used, which is associated with the time sequence of the closures, a significant difference in annual catch became apparent \(\left(F=7.23, p=0.015\right)\). Catches were highest in 2007, with a total of ca. 10 400 tonnes of small pelagic fish caught in Algoa Bay, and lowest during the last four years of our study (1100 tonnes in 2014 and 2016, 2900 tonnes in 2017 and 0 in 2015, Fig. 3). A Tukey post-hoc test showed that Open2 and Closed2 both significantly differed to Open1 (Figure S2) suggesting an overall decline in the annual catch rather than an effect of the closures on catch size.

Total annual catches (tonnes) of small pelagic fish by the purse-seine fishing industry in Algoa Bay, South Africa, during the various fishing exclusion regimes around St Croix Island between 2007 and 2017 (Open 1: 2007–2008, Closed 1: 2009–2011, Open 2: 2012–2014, Closed 2: 2015–2017). Different letters above box plots denote significant differences between periods

Discussion

Although considerable research exists on fishers’ support of conservation globally (e.g., Dimech et al. 2009; Leleu et al. 2012), the South African fishing community’s perceptions on marine conservation methods have not been well-studied. This study is the first to explore the perception of Eastern Cape purse-seine fishers in top-tier positions on marine conservation and the impacts of MPAs on the environment and on their industry. While the sample size of participants was small, interviews in this study aimed to explore perceptions and insights of pelagic fishers rather than ‘objective facts’ (Crouch and Mckenzie 2006). The perceptions and views are not generalised but remain the views of the participants. Therefore, the final sample size addressed the objectives of the study (see Daniel 2012). Interviews revealed that participants from the top-tier management of the small Algoa Bay purse-seine fishing industry tend to support conservation, although their views on which species should be protected and how, varied considerably with both age and position in the fishery. Their perception of potential impacts of fishing exclusion on their livelihoods was nonetheless mostly negative. There was, however, no evidence from their catch data or travelling time per fishing trip of any measurable impact, of a 20 km fishing exclusion around St Croix Island, on their industry. Rather, variability was apparent between vessels and the overall decline in annual catch sizes observed here follows the recent decrease in small pelagic fish stocks in South African waters, with the sardine stock now considered as depleted (van der Lingen 2021).

Most participants felt that marine predators play an important role in the ecosystem, a perception often observed in the fishing community worldwide (Drymon and Scyphers 2017). However, they disagreed on the need for protection for predators, with younger participants supporting marine predators’ conservation while older participants nuancing their statements by suggesting that only some should be protected. In the United States, older individuals were also less inclined to aid conservation of sharks (well-known marine predators) (Myrick and Evans 2014). The cause for this disparity of opinion with younger individuals was not clear, but it is possible that younger people have been taught more about fisheries decline through schooling as awareness of ocean conservation has developed over time (e.g., Lucrezi et al. 2019). It is unclear if that might be the case in the purse-seine fishing community in South Africa, but worth noting that it is a community dominated by older individuals (Sauer et al. 2003), which may affect how likely they may accept or be willing to be involved in conservation efforts. Regardless, further studies on the causes driving different views of the younger and older generations are needed to improve integrated ocean management efforts that aim to measure the impacts of sectoral management interventions on other sectors (for example, fishery closures on conservation and vice versa).

It is important to note that although participants recognised that overfishing was a serious issue globally and acknowledged that some fisheries were harmful to marine life, they did not feel that their fishery was a contributor. Rather, the responsibility of overfishing threatening marine ecosystems was systematically transferred onto other parties. This may be an example of Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons (Hardin 1968), a phenomenon in which an open resource leads to a lack of accountability and self-preservation trumps the needs of others. The issue of overfishing is complex, and no single party is entirely responsible, but the complexity of actors involved in overfishing makes it difficult to identify leverage points and responsible parties. This results in finger pointing and an absence of accountability across all parties. Hardin proposed that this “Tragedy of the Commons” can be avoided through greater state governance or private control of the resource. Ostrom (1990), instead, proposed that a shared resource can be responsibly managed by its users. Either way, the inclusion of all stakeholders for resource management and governance decisions is crucial to ensure that affected parties’ concerns are respectfully addressed, thus enabling a greater chance of success for the proposed management approach.

Participants were aware of the various benefits that MPAs and fishing-exclusion zones can provide, including benefits that did not directly influence the fishers or managers themselves (e.g., eco-tourism). This understanding suggests that close collaborations between MPA managers and fishers could be successful in improving MPA management and compliance (e.g., Russ and Alcala 2004; Leleu et al. 2012). However, factory managers tend to be more cognisant of MPA-related benefits than fishers, which may be partly explained by the differing reliance on sardine for an income. Fishers interviewed in this study had permits for small pelagic fish only, while managers were able to process a larger variety of fish at their factories. Fishers thus had fewer alternatives to withstand lower fish hauls, and this could reduce their willingness to support an MPA owing to its perceived impact on catches. While all nine participants agreed that MPAs have multiple environmental benefits, they all felt that they, as individuals, would be negatively impacted by the loss of fishing areas and income, potentially threatening their job security, a concern largely shared by fishers globally, especially if they have limited alternative fishing grounds (Rees et al. 2013; McClanahan et al. 2005). Algoa Bay is a relatively small area in which multiple industries (long-liners, trawlers, purse-seiners, shipping, aquaculture, etc., see Holness et al. 2022) are active, which may account for some of the perceived negative views of fishing-exclusion zones. Other studies have also shown that even in cases where fishers are supportive of MPAs, many do not want the MPA in their fishing areas – referred to as the ‘Not in my Backyard’ problem (Bohnsack 1993), as shown in this study. However, this response can also change with time by implementing awareness campaigns and educating stakeholders on the benefits of the MPA (Bohnsack 1993; Lucrezi et al. 2019), as mentioned by a participant in this study.

The negative perception of the impacts of MPAs on fishing catches could also be addressed if information and data can respectfully demonstrate the difference between perceived concerns and reality (e.g., Anderson and Nichols 2007; although see Nyhan and Reifler 2010). This study had access to the size and location of catches from the purse-seine fishing industry in Algoa Bay during various regimes of fishing exclusion around St Croix Island, which encompassed traditional fishing grounds (Pichegru et al. 2012) and is in close proximity to the Port Elizabeth harbour (Fig. 1). The exclusion was thus expected to negatively affect the travelling time of vessels operating from them harbour, forcing them to fish further from the harbour, and the restriction of the size of the fishing grounds accessible was also expected to affect overall catch sizes as strongly voiced in this study. None of these impacts were, however, apparent in our results. Similarly, other studies found no impact of even the world largest MPAs on the catches of the fishing fleets (e.g., Lynham et al. 2020, Favoretto et al. 2023). By contrast, spill-over effects of even mobile species have been repeatedly shown to increase catches of near-by fisheries (e.g., Medoff et al. 2022). Our results therefore suggest that a fishing-exclusion zone around one of the largest remaining African penguin colonies is unlikely to negatively affect the industry, while likely being beneficial towards the recovery of the African penguin population (Pichegru et al. 2010, 2012; Sherley et al. 2018). Fishing exclusions have been identified as a “recovery wedge” in strategies to rebuilding marine life for a sustainable future (Duarte et al. 2020). Given the uncertainty surrounding future climate scenarios and the environment (and human-use) responses to a changing environment, the precautionary principle (enshrined in South African environmental law) seems prudent.

An open dialogue and shift towards mutual trust between fishery and environmental authorities are necessary to allow for concerns to be voiced and respectfully assessed. In the present case, an open dialogue has been initiated to assist in easing concerns regarding income loss from an MPA, by first demonstrating that such loss was not supported by objective data. While fishers may benefit from a closer relationship with scientists and managers by being re-assured of the limited impacts of fishing exclusion on their livelihoods, scientists could also benefit from the wealth of knowledge held by fishers (Rochet et al. 2008). Fishers are inherently adaptable owing to the ever-changing nature of the environment in which they work. Given ever-changing oceanic conditions, and regular adjustments of fishing locations and allowed catches, some fishers have developed a profound understanding of their environment, allowing them to respond to change. Fishers’ knowledge of the ocean’s ecology, referred to as Local Ecological Knowledge (LEK) is an important key to better understanding how marine ecological communities function (Silvano and Valbo-Jorgensen 2008; Hallwass et al. 2013; Sowman and Raemaekers 2015; Lima et al. 2017). Research on LEK is just emerging in Algoa Bay (Strand et al. 2022), but remains nearly untapped globally within small pelagic fisheries (Uprety et al. 2012). This study may provide a foundation from which to build dialogue that will hopefully assist in MPA management and marine spatial planning efforts in the future. Successful MPAs and more integrated ocean management approaches require local involvement and input of stakeholders right at the start, as well as education actions, support from government agencies, and active monitoring and management (Pita et al. 2011; Boswell and Thornton 2021).

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to being part of a long-term monitoring project involving several researchers.

References

Anderson MH, Nichols ML (2007) Information gathering and changes in threat and opportunity perceptions. J Manag Studies 44:367–387

Bernard HR (2017) Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Rowan & Littlefield

Bohnsack JA (1993) Marine reserves: they enhance fisheries, reduce conflicts and protect resources. Oceanus 36:63–71

Boswell R, Thornton JL (2021) Including the Khoisan for a more inclusive Blue Economy in South Africa. J Indian Ocean Reg 17:141–160

Brander LM, Van Beukering P, Nijsten L, McVittie A, Baulcomb C, Eppink FV, van der Lelij JAC (2020) The global costs and benefits of expanding Marine protected Areas. Mar Pol 116:103953

Coetzee J, de Moor CL, Butterworth D (2019) A summary of the south african sardine (and anchovy) fishery. Cape Town. https://open.uct.ac.za/handle/11427/30645

Crawford RJM (2007) Food, fishing and seabirds in the Benguela upwelling system. J Ornithol 148:S253–S260

Crouch M, McKenzie H (2006) The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Social Sci Inform 45:483–499

Daniel J (2012) Choosing the size of the sample. Sampl Essentials: Practical Guidelines Mak Sampl Choices 2455:236–253

Davidson LN, Dulvy NK (2017) Global marine protected areas to prevent extinctions. Nat Ecol Evol 1(2):1–6

Dehens LA, Fanning LM (2018) What counts in making MPAs count: the role of legitimacy in MPA success in Canada. Ecol Indic 86:45–57

Dimech M, Darmanin M, Philip Smith I, Kaiser MJ, Schembri PJ (2009) Fishers ’ perception of a 35-year old exclusive Fisheries Management Zone. Biol Conserv 142:2691–2702

Drymon JM, Scyphers SB (2017) Attitudes and perceptions influence recreational angler support for shark conservation and fisheries sustainability. Mar Policy 81:153–159

Duarte CM, Agusti S, Barbier Eand 12 authors (2020) Rebuilding marine life. Nature 580:39–51

Favoretto F, Lopez-SAgastegui C, Sala E, Aburto-Oropeza O (2023) The largest fully protected marine area in North America does not harm industrial fishing. Sci Adv 9:eadg0709

Giakoumia S, McGowan J, Mills M, Beger M, Bustamante RH, Charles A et al (2018) Revisiting success and failure of Marine protected Areas: a conservation scientist perspective. Front Mar Sci 5:223

Grorud-Colvert K, Sullivan-Stack J, Roberts C, Constant V, Horta e Costa B, Pike EP et al (2021) The MPA Guide: a framework to achieve global goals for the ocean. Science 373:eabf0861

Hallwass G, Lopes PF, Juras AA, Silvano RAM (2013) Fishers’ knowledge identifies environmental changes and fish abundance trends in impounded tropical rivers. Ecol Appl 23:392–407

Hardin G (1968) The tragedy of the commons. Science 162:1243–1248

Holness SD, Harris LR, Chalmers R, De Vos D, Goodall V, Truter H, Oosthuizen A, Bernard AT, Cowley PD, da Silva C, Dicken M (2022) Using systematic conservation planning to align priority areas for biodiversity and nature-based activities in marine spatial planning: a real-world application in contested marine space. Biol Conserv 271:109574

Leleu K, Alban F, Pelletier D, Charbonnel E, Letourneur Y, Boudouresque CF (2012) Fishers ’ perceptions as indicators of the performance of Marine protected Areas (MPAs). Mar Policy 36:414–422

Lima MSP, Oliveira JEL, de Nóbrega MF, Lopes PFM (2017) The use of local ecological knowledge as a complementary approach to understand the temporal and spatial patters of fishery resource distribution. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 13:2069

Lucrezi S, Milanese M, Cerrano C, Palma M (2019) The influence of scuba diving experience on divers’ perceptions, and its implications for managing diving destinations. Plos One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219306

Lynham J, Nikolaev A, Raynor J, Vilela T, Villaseñor-Derbez JC (2020) Impact of two of the world’s largest protected areas on longline fishery catch rates. Nat Com 11:979

Majiedt PA, Holness S, Sink KJ, Reed J, Franken M, van der Bank MG et al (2019) “Pressures on marine biodiversity,” in South African National Biodiversity Assessment 2018 technical report volume 4: Marine realm, eds. J. Sink, K, M. G. van der Bank, P. A. Majiedt, L. R. Harris, L. J. Atkinson, S. P. Kirkman

Mann-Lang JB, Branch GM, Mann BQ, Sink KJ, Kirkman SP, Adams R (2021) Social and economic effects of marine protected areas in South Africa, with recommendations for future assessments. Afr J Mar Sci 43:367–387

McCauley DJ, Pinsky ML, Palumbi SR, Estes JA, Joyce FH, Warner RR (2015) Marine defaunation: animal loss in the global ocean. Science 347:1255641

McClanahan T, Davies J, Maina J (2005) Factors influencing resource users and managers ’ perceptions towards marine protected area management in Kenya. Environ Conserv 32:42–49

McInnes AM (2016) At-sea behavioural responses of African Penguins in relation to small-scale variability in prey distribution: implications for Marine Protected Areas. PhD thesis, University of Cape Town

McInnes AM, Ryan PG, Lacerda M, Deshayes J, Goschen WS, Pichegru L (2017) Small pelagic fish responses to fine-scale oceanographic conditions: implications for the endangered african penguin. Mar Ecol Progr Ser 569:187–203

Medoff S, Lynham J, Raynor J (2022) Spillover benefits from the world’s largest fully protected MPA. Science 378:313–316

Myrick JG, Evans SD (2014) Do PSAs take a bite out of Shark Week? The effects of juxtaposing environmental messages with violent images of shark attacks. Sci Commun 36:544–569

Nyhan B, Reifler J (2010). When corrections fail: the persistence of political misperceptions. Polit Behav 32:303–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9112-2

Ostrom E (1990) Governing the Commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, New York

Pichegru L, Grémillet D, Crawford RJM, Ryan PG (2010) Marine no-take zone rapidly benefits endangered penguin. Biol Lett 6:498–501

Pichegru L, Ryan PG, Le Bohec C, Van Der Lingen CD, Navarro R, Petersen S et al (2009) Overlap between vulnerable top predators and fisheries in the Benguela upwelling system: implications for marine protected areas. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 391:199–208

Pichegru L, Ryan PG, van Eeden R, Reid T, Gremillet D, Wanless R (2012) Industrial fishing, no-take zones and endangered penguins. Biol Conserv 156:117–125

Pita C, Pierce GJ, Theodossiou I, Macpherson K (2011) An overview of commercial fishers’ attitudes towards marine protected areas. Hydrobiologia 670:289–306

Rees SE, Rodwell LD, Searle S, Bell A (2013) Identifying the issues and options for managing the social impacts of Marine protected Areas on a small fishing community. Fish Res 146:51–58

Roberts CM, O’Leary BC, McCauley DJ, Cury PM, Duarte PM, Lubchenco J et al (2017) Marine reserves can mitigate and promote adaptation to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 114, 6167–6175

Rochet MN, Prigent M, Bertrand JA, Carpentier A, Coppin F, Delpech JP, Fontenelle G, Foucher E, Mahe K, Rostiaux E, Trenkel VM (2008) Ecosystem trends: evidence for agreement between fishers’ perceptions and scientific information. ICES J Mar Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsn062

Russ GR, Alcala AC (2004) Marine reserves: long-term protection is required for full recovery of predatory fish populations. Oecologia 138:622–627

Sala E, Mayorga J, Bradley D, Cabral RB, Atwood TB, Auber A, Cheung W, Costello C, Ferretti F, Friedlander AM, Gaines SD (2021) Protecting the global ocean for biodiversity, food and climate. Nature 592:397–402

SANBI, and South African Department of Environmental Affairs (2018) Marine Protected Areas South Africa https://www.marineprotectedareas.org.za/. i>https://www.marineprotectedareas.org.za/. Available at: https://www.marineprotectedareas.org.za/ [Accessed February 6, 2019].

Sardá R, Requena S, Dominguez-Carrió, Gili JM (2017) Ecosystem-based management for marine protected areas: a systematic approach. in Management of Marine protected Areas: A Network Perspective. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Sussex, UK, pp 145–162

Sauer WHH, Hecht T, Britz PJ, Mather D (2003) An economic and sectoral study of the south african fishing industry, vol 2. fishery profiles

Shannon LJ, Waller LJ (2021) A cursory look at the fishmeal/oil industry from an ecosystem persective. Front Ecol Evol 9:245

Sherley RB, Barham BJ, Barham PJ, Campbell KJ, Crawford RJM, Grigg J et al (2018) Bayesian inference reveals positive but subtle effects of experimental fishery closures on marine predator demographics. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20172443

Sherley RB, Crawford RJM, de Blocq AD, Dyer BM, Geldenhuys D, Hagen C, Kemper J, Makhado AB, Pichegru L, Upfold L, Visagie J, Waller LJ, Winker H (2020) The conservation status and population decline of the african penguin deconstructed in space and time. Ecol Evol 10:8506–8516

Sherley RB, Crawford RJM, Dyer BM, Makhado AB, Masotla M, Pichegru L, Pistorius PA, Ryan PG, Upfold L, Winker H (2019) The endangered status and conservation of Cape Gannets Morus capensis. Ostrich 90, 335–346

Silvano R, Valbo-Jorgensen J (2008) Beyond fishermen’s tales: contributions of fishers’ local ecological knowledge to fish ecology and fisheries management. Environ Dev Sustain 10:657–675

Smith MD, Lynham J, Sanchirico JN, Wilson JA (2010) Political economy of marine reserves: Understanding the role of opportunity costs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 107, 18300–18305

Sowman M, Raemaekers SJ (2015) Community level socio-ecological vulnerability assessments in the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem. Rome

Strand M, Rivers N, Snow B (2022) Reimagining ocean stewardship: arts-based methods to hear and see indigenous and local knowledge in ocean management. Front Mar Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.886632

Sydeman WJ, Hunt GL, Pikitch EK, Parrish JK, Piatt JF, Boersma PD, Kaufman L, Anderson DW, Thompson SA, Sherley RB (2021) South Africa’s experimental fisheries closures and recovery of the endangered African penguin. ICES J Mar Sci 78¸ 3538–3543

Uprety Y, Asselin H, Bergeron Y, Doyon F, Boucher J-F (2012) Contribution oftraditional knowledge to ecological restoration: practices and applications. Ecoscience 19:225–237

Van der Lingen CD (2021) Chap. 10: adapting to climate change in the south african small pelagic fishery. In: adaptive management of fisheries in response to climate change. FAO 667:177–194

Vermeulen EA, Clifford-Holmes JK, Scharler UM, Lombard AT (2022) A System Dynamics Model to support marine spatial planning in Algoa Bay, South Africa. Journal of Environmental Modelling and Software. (In review)

Wilkinson S, Japp D (2018) Basic assessment for a prospecting right application for offshore sea concession 6c West Coast, South Africa. Capricorn Marine Environmental

Worm B, Davis B, Kettemer L, Ward-Paige CA, Chapman D, Heithaus MR et al (2013) Global catches, exploitation rates and rebuilding options for sharks. Mar Policy 40:194–204

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to all fishers from Algoa Bay for their involvement in the interviews and engaging conversations. Also, thanks to Diya De Maine and Dennis Mostert for their support and assistance. Thanks to T. Wolff for assistance in data analyses.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa, and the Institute for Coastal and Marine Research and the Department of Zoology at Nelson Mandela University for funding and logistic assistance. ATL acknowledges additional support from the South African Research Chairs Initiative through the South African National Department of Science and Innovation/National Research Foundation (UID 98574), as well as Community of Practice grant in Marine Spatial Planning (UID 110612) from the same source.

Open access funding provided by Nelson Mandela University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors all contributed substantially to this work. First author TL conducted this study during her post-graduate study, co-supervised by all other authors. Last author, LP, was the main supervisor and conceptualized the study. All authors contributed to some aspects the design of the study, and/or to data analyses. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest, either financial, nor non-financial.

Ethics approval

Human ethics (H18-SCI-ZOO-004) approval was granted by the Nelson Mandela University human ethics committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gifford, T., Lombard, A.T., Snow, B. et al. Local purse-seine fishers’ economic losses owing to endangered seabird conservation measures – perceptions and reality. J Coast Conserv 27, 41 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-023-00974-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-023-00974-8