Abstract

In Indonesia, tourism has become a promising major economic sector, particularly because of its contributions toward developing the economy and creating employment opportunities for local communities with rich coastal ecosystems. However, the balance between the environmental, social, and economic realms has come into question, as unsustainable tourism practices continue to be promoted in Indonesia. To address such challenges, it is important to identify tourism impacts and provide sustainable policies and plans. Communities often record tourism impacts through their perceptions and act as important stakeholders in the process of sustainable tourism development. We examined tourism impacts on coastal ecosystems in Karimunjawa from the perspective of local communities. More comprehensively, we investigated their perceptions from three perspectives: socio-cultural, economic, and environmental. The study results revealed that the respondents held positive perceptions about tourism’s impact on socio-cultural and economic sectors and negative perceptions about its impact in the environmental domain. A chi-square test and Spearman’s correlation analysis indicated that the respondents’ educational attainment and tourism involvement influenced their perceptions on these issues. The current study results could be used as a baseline reference for contextualizing sustainable tourism plans regarding small island ecosystems in Indonesia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Indonesia is considered an attractive destination by tourists worldwide, and the tourism sector has contributed to overall GDP increase (Ahmad et al. 2019). In Indonesia, tourism development has been designed to reduce poverty and conserve the environment and natural resources (Sutawa, 2012). However, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), in certain tourist destinations, the country’s tourism sector is potentially growing too rapidly without due consideration of sustainability issues (Ollivaud and Haxton 2019). For instance, the large influx of tourists to tropical coastal areas can affect economic and ecological resources, which, in turn, can affect coastal ecosystems through land conversion and waste generation activities (Nelson et al. 2019). The situation will be exacerbated unless there is some intervention—for example, proper management of tourism activities that create societal issues and cause environmental degradation (Pascoe et al. 2014). Therefore, Indonesia’s government has introduced various special programs to promote sustainable tourism in coastal areas. At the provincial level, spatial plans have been introduced to regulate the use of coastal resources (i.e., mangrove ecosystems); for example, these regulate the utilization of such resources for tourism and educational activities and a list of prohibited activities (Lukman et al. 2019). Other examples of tourism-related management initiatives in the country include strict regulation of waste management through proper waste segregation processes (Ahmad et al. 2019), the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) as part of marine conservation policy (Bottema and Bush 2012), community-based tourism development (Ernawati et al. 2018), introduction of entry fees in marine parks (Pascoe et al. 2014), and community empowerment initiatives (Sutawa 2012).

In academic literature on sustainable tourism, one major contested issue concerns the empowerment of local communities. Community empowerment encompasses the psychological, social, and political spheres, which directly and significantly affect local communities’ perceptions of tourism (Boley et. 2014). According to Ahmad et al. (2019), governments should engage local communities in tourism promotion and environmental protection practices. Sutawa (2012) suggested that all stakeholders, including governments, non-government organizations (NGOs), and communities, should function as integral parts of sustainable tourism development and be involved in environmental degradation prevention processes. For instance, community involvement in the Bunaken National Marine Park, Indonesia, is highlighted as a key initiative for mitigating the impact of waste on the ocean (Tallei et al. 2013). Meanwhile, on Bali Island, the community’s engagement was identified as being vital for sustainable tourism development (Sutawa 2012); for example, the Pemuteran communities, which locally managed a coral reef restoration project, have received many international environmental and ecotourism awards (Trialfhianty and Suadi 2017). Thus, by involving residents in planning processes related to tourism development, governments can better reflect their concerns, which, in turn, could minimize any potential negative impacts (Jani 2018).

Successful tourism development tends to reflect local residents’ perceptions, and it is built on mutual relationships that are grounded in respect and cooperation between the tourism authorities and local communities (Change et al. 2018). Residents often strongly support tourism development when it positively affects the environment (Demirovic et al. 2018). A South African study showed that local communities’ perceptions of protected areas were important determinants for successful conservation efforts; that is, these perceptions affected people’s attitudes and behavior toward conservation (Ntuli et al. 2019). Another study reported that residents who were well-informed and involved themselves in tourism held more positive perceptions about it, while those who were less informed and less involved held negative perceptions of tourism activities (Lopes et al. 2019). However, several factors can influence residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts. For instance, tourism-related benefits could affect residents’ perceptions, so residents who have benefited from tourism may hold more positive perceptions, while those who have not benefited may hold negative perceptions (Brankov et al. 2019; Alves et al. 2013). One case study from Bohol Island in the Philippines showed that, regardless of any negative effects on the environment, community members welcomed tourism activities because of their expected benefits (e.g., alternative livelihoods) (Gier et al. 2017). The social exchange theory (SET) assumes that, in accordance with social behavior in an exchange process where people weigh the potential benefits and costs of any exercise, residents who feel that an “exchange” of tourism development for accompanying advantages will promote their prosperity will have positive reactions and support tourism development (Brankov et al. 2019; Ntuli et al. 2019). Community perception per se is defined as a function of the benefits and costs associated with tourism development, and when benefits outweigh costs, residents are more inclined to support development (e.g., Quevedo et al. 2021c).

This study investigated local residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts on coastal ecosystems in Karimunjawa, Indonesia; these perceptions can be divided into three dimensions with regard to sustainability: socio-cultural, economic, and environmental (Li et al. 2019; Demirovic et al. 2018; Almeida-Garcia et al. 2016). We primarily examined their perceptions and analyzed various variables that influenced their perceptions, including their involvement in the tourism industry and their priorities with regard to coastal ecosystem management. We noted that different socio-economic indicators could affect residents’ perceptions about tourism and attempted to develop more universal theories about tourism perception is needed (Demirovic et al. 2018; Brankov et al. 2019); furthermore, we analyzed research from various countries to identify differences and similarities, in terms of the influencing indicators for tourism-related perceptions, in order to draw contextualized policy implications. Furthermore, this study attempted to provide empirical evidence of public perceptions about tourism impacts on small island ecosystems and examine how this information could be used to implement better policies and environmental management processes.

Materials and Methodology

Study site: Karimunjawa

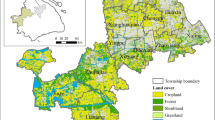

This study focused on assessing local residents’ perceptions regarding tourism impacts within Karimunjawa Island. Karimunjawa Island, a part of the Karimunjawa National Park (KNP), is covered by 1,285.5 hectares of tropical rainforest ecosystems (BTNKJ 2016); furthermore, it is home to diverse coastal ecosystems, and coral reef ecosystems form a major tourist attraction (BTNKJ 2014). Based on the 2019 report from Indonesia Statistics, Karimunjawa has a total population density of 4,946 of which 55% belonged to 20–59 age group, followed by 33% for 0–19 age group, and lastly 11% for 60 years old and above category (BPS Kabupaten Jepara 2020). Because of its accessibility, KNP holds huge potential in terms of the tourism industry (i.e., the presence of ports and airports). Tourists can also enjoy several attractions within the island including mangrove ecosystems and the area’s surrounding beaches. Based on the report from Central Java province government, the number of foreign tourists visiting Karimunjawa in 2017 is 6,917, while the domestic tourists number is 109,159 (Alamsyah 2017). According to Statistics Indonesia in 2019, the number of tourists visiting KNP reached 129,679, an increase of 12.7% compared to 2018; this increased the social and economic interactions between tourists and local people (Putro et al. 2020). The increasing numbers of tourists in Karimunjawa followed an increase in convenient transportation, although this area still lacks public infrastructure services (Kautsary 2017). With growing tourism industry, new employment and alternative livelihood opportunities will arise for the local communities. For instance, locals can work as a tour guide for snorkeling with a minimum income of Rp. 150,000/day, for diving with Rp. 250,000/day, and in other tourism-related services such as the hotel and transportation business (Qodriyatun 2018). Several studies have identified various environmental challenges in Karimunjawa. For instance, Karimunjawa has experienced several adverse impacts including damage to coral reefs through overfishing and destructive fishing, climate change, and declining water quality that is associated with tourism and mariculture (Kennedy et al. 2020). From the perspective of carrying capacity analysis for the clean water in Karimunjawa however, a study was conducted which highlights that the island still capable to provide clean water supply (Santoso et al. 2020). The rise of the tourism sector in Karimunjawa also led to an increase in CO2 emissions because of the use of private cars, ferries, and tour buses (Susanty and Saptadi 2020). Despite this growth in the local tourism industry, the poverty rate in Karimunjawa is 32%, and traditional farmers and fishers continue to live in extremely poor conditions (Setiawan et al. 2017).

Survey questionnaire

This study investigated local residents’ perceptions through face-to-face interview and a 3-part questionnaire applying a random sampling approach (adopted from Quevedo et al. 2020a, b) in several places which are covering main residential areas of the island to collect a representative response from overall people living in Karimunjawa. The survey sampling was supported by local university students. The first section of the questionnaire collected respondents’ personal information (henceforth, “profiles”), including age, gender, occupation, and education (modified from Lukman et al. 2020; Quevedo et al. 2020a). In the second section, respondents were asked to answer items about their perceptions regarding which coastal management activities should be prioritized. Seven activity types were listed in the questionnaire, and a comments section was provided for listing respondents’ additional management activities (if any), which may not have been included in the questionnaire. The seven activity types adopted by Quevedo et al. (2021a) were (1) organization strengthening and capacity development; (2) coastal and fisheries law enforcement; (3) fisheries management; (4) enterprise, livelihood, and tourism development; (5) information and education campaigns; (6) coastal zoning; and (7) habitat management and marine sanctuaries. Respondents were asked to rank these seven activities from the most prioritized (score 1) to the least prioritized (score 7).

The concept of highlighting these seven activities was based on Law No. 27/2007 on the Management of Coastal and Small Islands. Article 41 emphasizes organization and capacity development with regard to stakeholders as maritime partners in coastal management. The law enforcement mentioned in Article 36 highlights the need for monitoring the implementation of coastal ecosystem management in order to guarantee effective law enforcement in coastal and small island areas, where local communities can participate in such monitoring and enforcement. Article 23 describes the utilization of small Island ecosystems for the fisheries and tourism sectors; this highlights that such utilization should be integrated with ecological and economic perspectives. Article 47 explains the role of the government in establishing educational and training activities for developing human resources. Article 10 describes coastal zonation and details the Zonation Plan for Coastal and Small Islands Areas (RZWP3K) as an instrument for spatial planning. Article 28 provides aspects of habitat management and explains the necessity of conservation activities for protecting biodiversity, fish migration, marine organisms, and cultural sites in coastal and small islands. Figure 1 provides a summary version of Indonesia Law No. 27, 2007.

The third section recorded residents’ perceptions regarding tourism impacts. These impacts are divided into three broad categories: socio-cultural, economic, and environmental. According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), sustainable tourism should encourage optimal use of environmental resources, respect socio-cultural aspects of communities, and promote viable and long-term economic operations (Ernawati et al. 2018). Each category contained five to eight questions (adopted from Quevedo et al. 2021c). To record perceptions regarding tourism’s impact on socio-cultural aspects, we incorporated these six items: (1) variety of retail options; (2) options for shops and restaurants; (3) the number of recreational facilities and amenities in the area; (4) community strength and unitedness; (5) interaction with tourists; and (6) activity options in the town. To record perceptions regarding tourism’s impact on the economy, we listed these five items: (1) government investments in the area; (2) availability of jobs; (3) prices of goods and services in the area; (4) job competition between locals and outsiders; and (5) the number of available businesses. Last, to assess tourism impacts on the environment, we included these eight items: (1) availability and stocks of fish, shellfish, and other seafoods; (2) the condition of domestic waste management; (3) conditions of sewage systems; (4) conditions of beaches; (5) conditions of coral reefs; (6) conditions of seagrass ecosystems; (7) conditions of mangrove ecosystems; and (8) availability of fresh water. This section (“‘tourism impacts on the environment”) utilizes a Likert scale (range: −2 to 2; −2 = very negative impact, − 1 = negative impact, 0 = no impact, 1 = positive impact, and 2 = very positive impact). Furthermore, we asked respondents whether they were working in the tourism sector. The interview respondents were selected randomly, and the questionnaire survey utilized the native language Bahasa.

Statistical analysis and process

This study utilized descriptive statistics; correlations were used for analyzing information collected from the questionnaires. Descriptive statistics are used for summarizing data in an organized manner; relationships between variables in a sample or population are described, where they process condensed data into a simpler summary (Kaur et al. 2018). Descriptive statistics were used for visualizing the results from analysis of respondents’ socio-demographic profiles and the perception of tourism impacts on socio-cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions using mean (M) values to illustrate the perception of each item within the three categories. Cronbach’s alpha (α) is an important statistical concept for questionnaire evaluation, and it is commonly used for demonstrating that constructed tests and scales are fit for the desired research purpose (Tavakol and Dennick 2011; Taber 2017). Prior to the analysis, we used Cronbach’s alpha to calculate the internal reliability of the three categories (socio-cultural, economic, and environmental). The chi-square test is a statistical test for assessing whether two variables are associated with each other (Ugoni and Walker 1995; Rana and Singhal 2015). The chi-square test was used for evaluating whether the prioritization of coastal management and involvement in tourism sector-related occupations could be associated with local residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts. This test can also be used for analyzing perceptions regarding socio-cultural and economic factors, while the environmental perception test was separated (in terms of chi-square test analysis, which was performed for each item in the environmental category) to understand each item in the environmental category. The categories related to perception and prioritization were divided into two categories by calculating the average scores for the perception and priority scores. Then, the respondents were divided into two categories based on higher or lower scores for each perception and priority, while for tourism involvement, this category was simply divided into people who were involved in tourism and people who were not involved. We also performed a Spearman’s rank correlation analysis to analyze the association between perception of tourism impact and socio-demographic profiles. This analysis has been used previously in the context of a blue carbon ecosystem study to evaluate the relationships between awareness of benefits and the frequency of accessing the ecosystem (Quevedo et al. 2020a; Quevedo et al. 2021d). In this study, the socio-demographic profile was used for analyzing associations between tourism impact perceptions, education levels, and duration of stay in Karimunjawa.

Results

Respondents’ socio-demographic profiles

The interview involved 47 respondents. The study data were collected through face-to-face interviews with in-depth interactions; each interview, which utilized a questionnaire translated into Bahasa, had a duration of 40 to 60 min. The sample size of 47 was large enough for the chi-square test to be applied validly, which requires a minimum sample size that varies from 20 to 50 and has no expected cut-off (Rana and Singhal 2015). Table 1 summarizes the respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics. Most (51.06%) respondents had ages ranging between 41 and 50 years, followed by 31–40 years (29.79%), 20–30 years (12.77%), and 51–60 years (6.38%). In terms of gender, the majority of respondents were male (87.23%). The respondents’ education levels showed considerable variation across four categories: elementary school (23.4%), junior high (46.81%), senior high (19.15%), and college (10.63%). Furthermore, after asking the respondents about the duration of their stay in Karimunjawa (from the shortest to the longest), we found that respondents had been staying on the island for 1–5 years (4.26%), 6–10 years (6.38%), 11–15 years (8.51%), 16–20 years (23.4%), and more than 20 years (57.45%).

Perceptions regarding tourism impact

We first analyzed overall perceptions regarding the socio-cultural category (see Table 2). Respondents’ overall perception regarding socio-cultural impact was positive (M = 1.07, α = 0.85). An in-depth examination of each item within the socio-cultural context showed that variety of retail options was perceived positively (M = 0.85) along with other items including options for shops and restaurants (M = 1.04), the number of recreational facilities and amenities in the area (M = 1.04), community strength and unitedness (M = 1.25), interaction with tourists (M = 1.02), and activity options in the town (M = 1.21). Based on the percentage of the respondents, the item for activity options in the town received the highest number of positive responses, with 89.36% of respondents perceiving this item to be positively affected by tourism. Contrastingly, the item for variety of retail options had the highest number of respondents who perceived it in a negative manner, with respondents perceiving that this item would be negatively affected by the tourism sector—14.89% of them gave it negative scores.

Respondents from Karimunjawa also perceived the second category, tourism’s impact on economic aspects, positively (M = 1.18, α = 0.63), which is slightly higher than the socio-economic category; however, this had a lower level of reliability. We also observed each individual item in this category (see Table 3); government investments in the area was perceived positively (M = 1.06), and availability of jobs had received the highest average scores in the whole category (M = 1.44). The rest of the items (prices of goods and services in the area [M = 1.31], job competition between locals and outsiders [M = 0.78], and number of businesses available [M = 1.27]) were also perceived positively. Looking at the percentage of the respondents who perceived each item positively, the items availability of jobs, prices of goods and services in the area, and number of businesses available had the three highest values; 87.23%, 91.49%, and 93.62% of respondents, respectively, assigned them positive scores. Meanwhile, the item job competition between locals and outsiders received the highest negative score in the economic category; 6.38% of respondents perceived tourism as having a negative impact on job competition.

Regarding the environmental category, the results contrasted with those of the socio-cultural and economic categories. The respondents perceived tourism as having a negative impact on the environment (M = − 0.04, α = 0.84). Although the overall score was relatively close to indicating “neutrality/no impact,” an examination of individual items showed that a few environmental aspects were perceived to be negatively affected by tourism (Table 4). The items that received negative scores were availability and stocks of fish, shellfish, and other seafoods (M = − 0.21), the condition of domestic waste management (M = − 0.06), conditions of sewage systems (M = − 0.17), conditions of coral reefs (M = − 0.17), and availability of fresh water (M = − 0.23), while the items conditions of beaches (M = 0.319), conditions of seagrass ecosystems (M = 0.08), and conditions of mangrove ecosystems (M = 0.08) were perceived in a relatively positive manner. Looking at the percentages of respondents who assigned positive and negative scores, we captured several different results for each item. Regarding the item the condition of domestic waste management and conditions of sewage systems, the respondents’ perceptions were almost equally divided between those who perceived the items to be positively affected (44.68% and 45.65%, respectively), and those who perceived them to be negatively affected (46.81% and 45.65%, respectively). Some items received negative scores from most of the respondents—namely, conditions of coral reefs (44.68%) and availability of fresh water (40.43%). Interestingly, availability and stocks of fish, shellfish, and other seafoods was the item where the highest percentage of respondents perceived that tourism would not have a significant impact; 48.94% of the respondents assigned it with a score of 0.

Correlations among the studied parameters

Regarding the 47 respondents’ assigned scores, the average score for management priority in Karimunjawa was 4.57 (M); 22 respondents assigned lower management scores (priority for tourism management), and the other 25 respondents assigned higher management scores (priority for other types of coastal management). Based on the chi-square test regarding the average scores for socio-cultural perception and economic perception, neither result was statistically significant; both had p-values higher than 0.05 (socio-cultural and economic). An examination of the results of the chi-square test using the category of involvement in the tourism sector showed that a smaller number of samples could be used in this test; 20 respondents were not involved in the tourism sector, and 19 respondents were involved in the tourism sector. Eight respondents who did not give answers regarding their involvement in the tourism sector were excluded from this test. The chi-square test results involving socio-cultural perception showed a statistically significant result (p < 0.01); people who were involved in the tourism sector showed a more positive perception of the impact of tourism on the socio-cultural category. However, regarding economic perception, the chi-square test yielded a statistically insignificant result (p > 0.05). Table 5 shows the chi-square test (p-value) results for the socio-cultural and economic categories.

The chi-square test for environmental perception, which focused on each item, and the association of environmental perception with management priority showed one result that was statistically significant (p < 0.05)—that is, for the conditions of seagrass ecosystems. The results showed that respondents with higher management scores (a priority for coastal management activities besides tourism) had a lower negative perception of conditions of seagrass ecosystems, which can be interpreted to mean that these respondents perceived tourism as having a negative impact on the conditions of the seagrass ecosystems. The other environmental perception items regarding management priority did not show any statistically significant results. Viewing the perspective of involvement in tourism with regard to environmental perception, two items provided statistically significant results: conditions of seagrass ecosystems (p < 0.05) and conditions of mangrove ecosystems (p < 0.05). Regarding these items, respondents involved in the tourism sector had a lower perception—that is, they perceived tourism as having a negative impact on the seagrass and mangrove ecosystems. The other five items within the environmental category did not produce statistically significant results. Table 6 presents the results of the chi-square test (p-value) for the environmental category.

The Spearman correlation analysis of socio-demographic profiles with regard to the three perception categories (socio-cultural, economic, and environmental) showed statistically significant results for socio-demographic aspects related to education level (see Table 7). The observed effect of education level negatively influenced the perception of tourism’s impact on the environment (ρ = −0.397, p < 0.01). However, there were no statistically significant results for the influence of education level on socio-cultural and economic perceptions or for the influence of duration of stay in Karimunjawa on the three perception categories.

Discussions

Locals’ perceptions of tourism impacts

In this paper, we first discussed the three domains: socio-cultural, economic, and environmental. The interactions of these three domains with other indicators (e.g., tourism involvement, management priority, and so on) are discussed at the end of sub-Sect. 4.2. In Karimunjawa, local residents’ overall tourism impact-related perceptions were positive for the socio-cultural and economic realms. In short, this study confirmed certain trends that emerged in existing studies—for example, tourism was generally perceived to have a positive impact on socio-economic dimensions but unfavorably with regard to the environment, as was the case in Ubud, Indonesia (Ernawati et al. 2018). Other positive effects from existing studies were also confirmed in the Karimunjawa case—for example, tourism was perceived to indicate economic development, cultural protection, and infrastructure improvement, as was the case in China (cf. Li et al. 2019).

Socio-cultural domain

Regarding socio-cultural impact, several items, especially interaction with tourists, were perceived positively by local residents in Karimunjawa. This strong positive perception of tourists indicated the absence of any xenophobic feelings toward tourists from the local population (Brankov et al. 2019). Instead, the local residents were interested in participating in tourism-related activities (Setiawan et al. 2017). We argue that this positive perception expressed by the residents was related to the positive situation of tourism in Karimunjawa; the locals perceived tourism to be mostly beneficial. Through the off-the-record points, which we did not include in the questionnaire but discussed with locals, we also captured how they were eager to communicate, especially with foreign tourists, in the hope of learning and exercising a new language. Perceptions regarding tourist behaviors can have a positive influence on locals’ attitudes and behaviors; more positive perceptions of tourists’ respectful behavior could result in a greater overall positive perception (Vargas-Sanchez et al. 2011).

The second point concerned local residents’ high positive perception of tourism impacts on community strength and unity. We argue that locals linked tourism to community initiatives on the island. Past research has identified community empowerment as a key factor for tourism development; it can help to reduce tourism’s negative impacts, thus leading to the development of a more sustainable tourism (Sutawa 2012). However, there are some concerns about the potential conflict, in terms of authority and power sharing, between various stakeholders and the community; thus, the government and community in Karimunjawa need to stay well informed about locals’ perceptions about tourism development in order to achieve cooperative development. A study from Wibowo et al. (2018) on community participation in Karimunjawa reported that community knowledge and obedience to rules of area zonation was widespread from the fishermen community who already had the knowledge and understanding, although the overall local residents’ participation in coastal ecosystem management was low to medium which showed that there were many who didn’t have enough knowledge of Karimunjawa zonation system.

Economic domain

The second perception category, tourism’s impact on the economic sector, was also perceived positively. The tourism sector has the potential to yield foreign exchange, attract international investments, increase tax revenues, and create new opportunities for employment (Setiawan et al. 2017). Tourism activities that do not result in rapid infrastructure development could positively influence perceptions of tourism and its future development because of currently limited employment opportunities in this region (Brankov et al. 2019). Employment opportunities form a major reason for locals’ positive perception of tourism impacts. During the pre-COVID-19 period, tourism was a thriving industry in Karimunjawa until 2019 (Setiawan et al. 2017). The benefits received from the tourism sector and the thriving tourism industry might have shaped residents’ positive tourism-related perceptions, as they might have expected the same benefits or possibly better outcomes to accrue in the long-term. Residents’ positive attitudes could be connected to the belief that tourism creates new jobs for the local population and fosters the development of the local culture and community (Brankov et al. 2019).

Environment

The perception of tourism’s impact on the environment was the only category where locals perceive tourism impacts in a negative manner. The first concern was tourism’s negative impact on fisheries and seafood stocks. There are seven zones within the KNP, one of which is the utilization zone where fishers operate; however, their catch has decreased due to their use of destructive technology (Simbolon et al. 2016). “No-take” areas (for example, inside tourism zones) have been introduced with the aim of improving fisheries; these areas are unlikely to impact the fishers (e.g., in terms of possible displacement from “no-take” areas). However, there could be displacement of fishing efforts from areas that received greater enforcement (e.g., inside tourism zones). In Karimunjawa, there has been weak compliance with “no-take” areas regulations and a lack of targeted fishing gear controls; this may have promoted competition and conflict among the fishers (Campbell et al. 2014).

In KNP, zonation was legislated in 1989 by the authorities with negligible stakeholder input (Campbell et al. 2012). According to the document of Strategic Plan KNP period 2020–2024, the issues of (1) mangrove illegal logging, (2) conflict of community with wild animals (3) decrease coverage of coral reefs, and (4) tourism development were stated (BTNKJ 2020), in which the document formulated several strategies from various sector to coordinate and achieve the KNP goals of conservation managements. Later a set of zones incorporating community and stakeholder knowledge, which included “no-take” core and protection zones, “traditional” fishing utilization zones, and zones that permitted specific activities, such as tourism zones, rehabilitation zones, and mariculture zones, were introduced. In KNP, tourism activities are permitted in the tourism, rehabilitation, aquaculture, and utilization zones, while fishing activities are only allowed in the rehabilitation and utilization zones (Yulianto et al. 2015). We argue that the overlap—that is, tourists being allowed to access the utilization and rehabilitation zones—could have influenced the fishing community’s concerns about negative tourism impacts, resulting in their overall negative perceptions of tourism. However, pressures on fisheries may also originate in some other sectors aside from tourism. Overfishing is a concern in KNP, and various potential threat activities have been identified, including legal fishing, illegal fishing, coastal development (including tourism), seaweed mariculture, grouper aquaculture, and climate change; these concerns should be addressed in order to achieve desired outcomes for fisheries intervention (Battista et al. 2017).

The condition of waste and sewerage management in Karimunjawa is another item that received negative perceptions. There seem to be no straightforward solutions for waste management on small islands because of various issues including limited space, restricted recycling, dense population, and dependence on tourism (Camilleri-Fenech et al. 2018). We argue that the issue of waste management in Karimunjawa also played a relevant role in shaping local residents’ perceptions regarding tourism impacts. These concerns and challenges should not be simply attributed to tourists’ bad behaviors, as the issue of Island waste management includes various aspects of limited land resources, high energy, costs, large seasonal fluctuation in waste volumes, and complex social and political dynamics (Eckelman et al. 2014).

The off-the-record interview discussions with the locals captured their concerns about the waste management system in Karimunjawa in terms of waste collection and disposal sites. According to recent news from August 2020, a newly established facility for recycling waste went into operation in Karimunjawa with financial support from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of Indonesia. The facility is expected to store 10 tons of waste per day and reduce the plastic waste that leaks to the ocean by 75% (Cahyana 2020). Another source (Erje 2020) raised the concern that domestic waste is generated by locals and the tourism activity within the Karimunjawa area, with a total daily waste production reaching 5.6 tons. A robust waste management system is thus critical for both tourism and local environments in terms of supporting infrastructures in the area. Furthermore, various waste reduction initiatives should also be considered—for example, involving the community and tourists in relevant environmental conservation campaigns. This situation presents some opportunities for implementing island waste management strategies (for example, from small businesses for niche recycling and manufacturing markets (Eckelman et al. 2014), or through composting organic waste, which can ultimately reduce 60% of municipal solid waste (Mohee et al. 2015).

The next discussion point in this regard is the diverse ecosystems in Karimunjawa, which hold potential benefits for the tourism sector. Field observation has shown that one common business objective of the tourism sector in Karimunjawa is developing tourist resort businesses; this utilizes the beautiful scenery of nearby coastal ecosystems. Most experts agree that an increasing number of potential pressures have been caused by tourism activities in Karimunjawa (Prasetya et al. 2018). This notion is also evident in locals’ perception of tourism impacts on the coral reef ecosystem; this has resulted in their negative perceptions of tourism. Coastal tourist areas are often centered around fragile ecosystems, including coral reefs (Nelson et al. 2019). The status quo of pressures on coral reefs and Karimunjawa’s reliance on tourism related to the coral reef ecosystems have made enforcing legal regulations for protecting coral reef ecosystems vital. Based on a study from Akhmad et al. (2018), it was reported that the increase of snorkeling tourists in Karimunjawa can cause ecological pressure on coral reefs at snorkeling sites, with the damage of the coral reefs in partial form such as eroded surface. At the same time, snorkeling in Karimunjawa holds potential economic value of 94,549,044 IDR/year, with the tourism demand is indirectly related to the condition of the quantity and quality of the coral reef (Mazaya et al. 2019).

Water availability formed the last source of locals’ tourism-related negative perceptions in the environmental category. Large tourist influxes can increase pressures on energy and water needs (Nelson et al., 2019). After the interview, we received several comments from the respondents, voicing their concerns about the water supply in Karimunjawa, especially during the drought season when they needed to buy water at higher prices; on some occasions, there was not enough water for consumption. Hotel construction requires adequate communal infrastructure, including drinking water provision and water treatment plants (Demirovic et al. 2018).

Overall, based on our findings of negative environmental perceptions, we argue the importance of addressing environmental pressures in Karimunjawa. A study on the Pärnu Bay region, where strict coastal protection measures are considered to be too expensive and not reasonable in terms of implementation, recommended the development of alternative adaptation measures and raising awareness as applicable response options (Tõnisson et al. 2019). We argue that, in the Karimunjawa case, it is important to make efforts to raising awareness of tourism and the environment. Residents who perceive tourism as having positive effects on the environment will generate stronger support for tourism development (Demirovic et al. 2018). However, in Karimunjawa, the contribution of tourists should also be considered important. Tourists can contribute toward improving the environment by adopting pro-environment attitudes and proper behaviors (Stefanica and Butnaru 2015). Despite the overall negative perception observed in this study, there is the notion to utilize the marine resources, such as coral reef, as an alternative livelihood for the locals. Study from Setiawan et al. (2017) reported that poor households in Karimunjawa are willing to be involved in the tourism sector provided that they are given employment opportunities and ensure an increase in their income. This situation illustrates that there are two perspective sides of the concern from the locals on the negative impact of tourism, but at the same time there is also the need to expand the tourism sector to improve the local economy of Karimunjawa. Future study should consider these trade-offs between economy from tourism and the impact to environment to better understand the local’s perception on their priority. While other ecosystems, including mangroves, seagrass systems, and beaches, can be positively impacted by tourism, initial initiatives should focus on implementing programs for protecting and preserving these ecosystems; this should be followed by implementation of similar initiatives for other threatened ecosystems such as coral reefs. For example, tangible procedures and law enforcement can be implemented to reduce the economic losses related to destruction of coral reefs (Haya and Fujii 2019). Furthermore, discussion on the ecosystem services in the boundary of coastal settings need to take place, such as the potential of blue carbon ecosystems services in mangroves and seagrass as marine resources in the utilization for carbon sequestration and tourism activities. Blue carbon ecosystem services of carbon sequestration in the mangrove and seagrass ecosystem in Karimunjawa was reported to be moderately aware by the locals, and in general the blue carbon functions are unrecognized compared with the services as coastal protection (Quevedo et al. 2021a). In future research, information of emissions from tourism sector and carbon sequestration function of blue carbon ecosystem can be shared with local residents as scientific evidence to support them to evaluate the status of coastal environment.

Interaction effects on perception: Influence of tourism involvement, management priority, and education level on perceptions of tourism impact

Socio-cultural and Economic domains.

Our correlation analysis results showed that locals’ involvement in the tourism sector influences their positive perception of the socio-cultural category but not the economic one. People employed in tourism and their family members often hold more positive opinions about tourism impacts (Brankov et al. 2019). In previous studies, residents who were more informed and more involved often held more positive perceptions of tourism; thus, tourism development initiatives must consult with local residents while considering the different needs of the communities (Lopes et al. 2019). The people of Karimunjawa Island were eager to interact with tourists in a socio-cultural manner, thus influencing the positive perception toward this category. Regarding the economic category, however, our analysis showed that tourism involvement was not related to their positive perception of tourism’s impact on the economy. We argue that this finding is related to current development levels on Karimunjawa Island. Our survey showed that level of tourism development on Karimunjawa Island was low. Infrastructures such as roads, facilities, and commerce sectors were still deficient and somehow centralized to only one area. While low-to-moderate tourism development is currently perceived as being beneficial, residents’ perceptions in this regard could change to negative as the area develops (Vargas-Sanchez et al. 2011). In a similar vein, overall perceptions of economic and socio-cultural categories in Karimunjawa were positive. Meanwhile, our analysis of management priority did not detect any significant relationship with perception. We argue that prioritization of management by itself did not provide any direct benefits to the residents; thus, no direct relationships were observed in this regard.

Environmental.

The locals’ negative perceptions of the impact of tourism on the environment was observed among by those involved in tourism, who indicated a positive relationship with concerns regarding seagrass ecosystems and mangrove ecosystems. In other words, respondents who were involved in the tourism sector perceive tourism as a potential threat to the environment. It should be noted that seagrass systems form a concerning ecosystem in terms of tourism development-related ecological threats in Karimunjawa. One study involving the Karimunjawa Islands, particularly the waters around Menjangan Kecil and Menjangan Besar, showed that between the two study sites, the area with higher seagrass density had higher fish abundance and species numbers (Susilo et al. 2018). In Berau, East Kalimantan, Indonesia, the fishing communities reported changes and degradation in the seagrass ecosystems (Lukman et al. 2020). We argue that the situation might be similar in Karimunjawa Island because the locals involved in tourism tend to notice the accompanying changes in the seagrass and mangrove ecosystems; simultaneously, they have witnessed the development of tourism, and this has shaped their negative perceptions regarding tourism. Furthermore, exposure to tourists’ negative behaviors with regard to the environment could also shape locals’ negative perceptions of the tourism sector. Initiatives, including social marketing in the tourism industry, to promote pro-environmental behaviors could also contribute toward helping tourists develop more positive environment-related behaviors and attitudes (Tkaczynski et al. 2020). Tourism stakeholders must consider regulating tourists’ behaviors within Karimunjawa Island because involvement with locals to protect the beauty of the island’s environment may yield much more desirable results. The approach of synergizing environmental conservation with socio-economic dimension of Karimunjawa can also be considered. For example, in Gili Trawangan case, tourists can show their support on the conservation effort through the implementation of entry/exit fees, voluntary contributions, taxes, and licensing fees (Nelson et al. 2019), as well as in the Bunaken National Marine park with user fees being utilized to address environmental and equity issues (Pascoe et al. 2014).

Finally, the environmental perception was analyzed using the Spearman-rank analysis results. The duration of stay did not influence perception, while education level showed a negative correlation with perception. This finding may be ascribed to the fact that the deterioration in the environment had proceeded in a gradual manner, and therefore the duration of living years did not influence perception. The locals had gradually become accustomed to situations such as the lower catches in the fisheries sector. In other contexts, living at the site for more than 10 years was reported to be a predictor of negative attitudes toward tourism development; this was the case in one study conducted in Benalmadena, Spain, which argued that, when residents lived in the area for a longer period, they witnessed many negative changes and tended to miss the “good old days” (Almeida-Garcia et al. 2016). Regarding the level of education, we found that it negatively influenced the perception of tourism’s impact on the environment; thus, as the education level increases, the perception of tourism’s impact on the environment deteriorates. These results contrasted with those of previous studies. For example, in Spain, the level of education was a strong predictor of positive attitudes toward tourism’s effects; respondents with higher education levels tended to perceive tourism’s impacts more positively (Almeida-Garcia et al. 2016). In Argentina, tourism-related positive perceptions were influenced by reaching the secondary level of education; education significantly improved this perception (Castilla et al. 2020). In the case of Karimunjawa, education did not necessarily translate into a positive perception of the tourism industry; however, it allowed locals to understand the potential benefits of tourism. Highly educated respondents’ low level of involvement may have affected their lack of positive perceptions of tourism’s impact on the environment. Educated people’s understanding of the current conditions of pressures and threats to the island from various sectors, including tourism, might have shaped their overall negative perception. Relevant stakeholders’ inability to initiate relevant efforts, or perhaps related stakeholders’ lack of involvement in encouraging potential human resources to contribute toward environment conservation may exacerbate this situation. We suggest that official bodies should identify and involve potential human resources, such as teachers and NGO members, in these efforts because they have the potential to generate support from local residents in general. Nonetheless, there is also another context on the difference with the case of Spain and Argentine. In Spain, the residents with lower education levels consider themselves less likely to get a job and benefit from tourism, hence they have more critical view and perceived tourism in negative way and prefer to maintain traditional way of life (Almeida-Garcia et al. 2016). For the Argentina case, higher level of education is linked with the condition of the school in the area addressed the topic in science manner for the object of tourism (Castilla et al. 2020). School education can provide scientific and standardized knowledge, however, it should be noted that scientific knowledge itself is a tool which can be utilized to evaluate the status of local environment. Future studies should also consider different socio-economic indicators, such as length of stay, that may affect residents’ perception in order to develop more universal theories about tourism perception (Brankov et al. 2019), as well as the context from local wisdom and values which can influence the community perception to tourism. Another approach should aim to deepen causal relationships between environmental management factors and impact assessment. This includes analysis based on perspectives of management related drivers, including the drivers, pressures, states, impacts, and responses (DPSIR) model (Kohsaka 2010; Quevedo et al. 2021b), and the accessibility of tourism resources and locals’ perceptions regarding such resources (Uchiyama and Kohsaka 2016).

Conclusion

This study investigated a small Island community’s perception of tourism impacts from three perspectives: socio-culture, economics, and environment. We identified that locals in Karimunjawa Island perceived the tourism sector to have a positive impact on the socio-cultural and economic domains but a negative impact on the environmental realm. We traced back the factors that shaped these perceptions by using the dimensions of local tourism sector involvement and management priority; both dimensions helped local residents understand and receive the benefits of the tourism sector. Simultaneously, we also observed how locals tended to notice environmental degradations within the context of tourism development and factors, such as levels of education, that influenced the locals’ understanding of the benefits and threats of the tourism industry.

Our findings could contribute toward understanding the factors that influence tourism impact-related perceptions. However, there are challenges in these methodologies. We suggest that two future research tasks should be conducted with regard to the perceptions and relationships of the variables. Our findings are based largely on face-to-face surveys of locals; this can be further combined with an in-depth analysis of the perceptions of specific actors (perceptions of municipality officials, as in Kohsaka et al. 2019) and analysis of policy processes (cf. text analysis of debate in municipality councils; Kohsaka and Matsuoka 2015). Although our study did not find any direct insight with regard to length of stay, we recommend further investigation of the intricacies of other related factors including environmental changes or incidents perceived in recent years. Such multi-layered analyses could enrich our understanding regarding various indicators that influence perception and can thus provide better and more comprehensive understandings related to perception studies.

Furthermore, tourism stakeholders’ (such as NGOs and government officials) attitudes and perceptions are necessary for identifying differences and similarities and drawing policy implications (Demirovic et al. 2018). This study’s major contribution is to offer a design process for comprehensive coastal ecosystem management that integrates fisheries and tourism; furthermore, it suggested that involving the local community is crucial for helping them access and understand locales with regard to the current status of the island in the context of tourism development. It also explored how the related stakeholders can initiate a movement for environmental conservation; these findings could guide the residents of Karimunjawa in benefiting from the tourism sector but also in preserving their environment.

References

Ahmad F, Draz MU, Su L, Rauf A (2019) Taking the bad with the good: The nexus between tourism and environmental degradation in the lower middle-income Southeast Asian economies. J Clean Prod 233:1240–1249

Akhmad DS, Supriharyono, Purnomo PW (2018) Potensi Kerusakan Terumbu Karang Pada Kegiatan Wisata Snorkeling Di Destinasi Wisata Taman Nasional Karimunjawa (Potential Damage to Coral Reef on Snorkeling Activities in Karimunjawa National Park Tourism Destination). Jurnal Ilmu dan Teknologi Kelautan Tropis. 10(2), 419–429. Bahasa

Alamsyah IBK (2017) Karimunjawa Sebagai Destinasi Pariwisata Unggulan Melalui Marketing Collaboration System. Diklatpim Tingkat III Angkatan XXXIV. Bahasa. https://bpsdmd.jatengprov.go.id/eproper/cetakinovasi/?nourut=1125

Almeida-Garcia F, Pelaez-Fernandez MA, Balbuena-Vazquez A, Cortes-Macias R (2016) Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tourism Manage 54:259–274

Alves LCPS, Zappes CA, Oliveira RG, Andriolo A, Azevedo ADF (2013) Perception of local inhabitants regarding the socioeconomic impact of tourism focused on provisioning wild dolphins in Novo Airão, Central Amazon, Brazil. An Acad Bras Cienc 85(4): 1577–1591

BTNKJ (Balai Taman Nasional Karimunjawa) (2014) Kementerian Kehutanan Direktorat Jenderal Perlindungan Hutan dan Konservasi Alam. Bahasa

BTNKJ (Balai Taman Nasional Karimunjawa) (2016) Statistik Balai Taman Nasional Karimunjawa Tahun 2015.Kementerian Kehutanan Direktorat Jenderal Perlindungan Hutan dan Konservasi Alam. Bahasa

BTNKJ (Balai Taman Nasional Karimunjawa) (2020) Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup & Kehutanan Direktorat Jenderal Konservasi Sumberdaya Alam & Ekosistem

Battista W, Karr K, Sarto N, Fujita R (2017) Comprehensive Assessment of Risk to Ecosystems (CARE): A cumulative ecosystem risk assessment tool. Fisheries Res 185:115–129

Boley BB, McGehee NG, Perdue RR, Long P (2014) Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Annals of Tourism Research 49:33–50

Bottema MJM, Bush SR (2012) The durability of private sector-led marine conservation: A case study of two entrepreneurial marine protected areas in Indonesia. Ocean & Coastal Management 61:38–48

BPS Kabupaten Jepara (2020) Kecamatan Karimunjawa Dalam Angka 2020. BPS Kabupaten Jepara

Brankov J, Glavonjic TJ, Pesic AM, Petrovic MD, Tretiakova TN (2019) Residents’ Perceptions of Tourism Impact on Community in National Parks in Serbia. Europ Countrys 11(1):124–142

Cahyana L 2020. Kiat Kepulauan Karimunjawa Mengatasi Sampah Plastik (Strategy of Karimunjawa Island to Manage Plastic Waste). Tempo.Co (Accessed on: 1 December 2020 https://travel.tempo.co/read/1380027/kiat-kepulauan-karimunjawa-mengatasi-sampah-plastik). Bahasa

Camilleri-Fenech M, Oliver-Sola J, Farreny R, Gabarrell X (2018) Where do islands put their waste? – A material flow and carbon footprint analysis of municipal waste management in the Maltese Islands. J Clean Prod 195:1609–1619

Campbell SJ, Hoey AS, Maynard J, Kartawijaya T, Cinner J, Graham NAJ, Baird AH (2012) Weak Compliance Undermines the Success of No-Take Zones in a Large Government-Controlled Marine Protected Area. PLOS ONE 7(11):1–12

Campbell SJ, Mukminin A, Kartawijaya T, Huchery C, Cinner JE (2014) Changes in a coral reef fishery along a gradient of fishing pressure in an Indonesian marine protected area. Aquat Conserv: Mar Freshw Ecosyst 24:92–103

Castilla MC, Campos C, Colantonio S, Diaz M (2020) Perceptions and attitudes of the local people towards bats in the surroundings of the big colony of Tadarida brasiliensis, in the Escaba dam (Tucumán, Argentina). Ethnobiol Conserv 9(9):1–14

Chang KG, Chien H, Cheng H, Chen H (2018) The Impacts of Tourism Development in Rural Indigenous Destinations: An Investigation of the Local Residents’ Perception Using Choice Modeling. Sustainability 10:1–15

Demirovic D, Radovanovic M, Petrovic MD, Cimbaljevic M, Vuksanovic N, Vukovic DB (2018) Environmental and Community Stability of a Mountain Destination: An Analysis of Residents’ Perception. Sustainability 10:1–16

Eckelman MJ, Ashton W, Arakaki Y, Hanaki K, Nagashima S, Malone-Lee LC (2014) Island Waste Management Systems Statistics, Challenges, and Opportunities for Applied Industrial Ecology. J Ind Ecol 18(2):306–317

Erje B (2020) DLH Jepara Prediksi Masalah Sampah Bakal Jadi Momok Pengembangan Wisata di Karimunjawa (Jepara Government Agency Predict Waste Issue will be the threat for Tourism Development in Karimunjawa). Murianews (Accessed on: 1 December 2020 https://www.murianews.com/2020/08/24/194016/dlh-jepara-prediksi-masalah-sampah-bakal-jadi-momok-pengembangan-wisata-di-karimunjawa.html). Bahasa

Ernawati NM, Sudarmini NM, Sukmawati NMR (2018) Impacts of Tourism in Ubud Bali Indonesia: a community-based tourism perspective. IOP Conf Series: Journal of Physics: Conf Series 953:1–9

Gier L, Christie P, Amolo R (2017) Community perceptions of scuba dive tourism development in Bien Unido, Bohol Island, Philippines. J Coast Conserv 21:153–166

Haya LOMY, Fujii M (2019) Assessing economic values of coral reefs in the Pangkajene and Kepulauan Regency, Spermonde Archipelago, Indonesia. J Coast Conserv 23, 699–711 (2019)

Jani D (2018) Residents’ perception of tourism impacts in Kilimanjaro: An integration of the Social Exchange Theory. Tourism 66(2):148–160

Kaur P, Stoltzfus J, Yellapu V (2018) Descriptive statistics. Biostatistics. 4 (1), 60–63

Kautsary J (2017) Public Infrastructure Problem For Developing Tourism Destinations In Coastal And Small Islands Areas Case Study In Karimunjawa Archipelago. Proceedings of International Conference: Problem, Solution and Development of Coastal and Delta Areas. 625–633

Kennedy EV et al (2020) Coral Reef Community Changes in Karimunjawa National Park, Indonesia: Assessing the Efficacy of Management in the Face of Local and Global Stressors. J Mar Sci Eng 8:1–27

Kohsaka R (2010) Developing biodiversity indicators for cities: applying the DPSIR model to Nagoya and integrating social and ecological aspects. Ecol Res 25(5):925–936

Kohsaka R, Matsuoka H (2015) Analysis of Japanese municipalities with Geopark, MAB, and GIAHS certification: quantitative approach to official records with text-mining methods. SAGE Open 5(4):1–10

Kohsaka R, Matsuoka H, Uchiyama Y, Rogel M (2019) Regional management and biodiversity conservation in GIAHS: text analysis of municipal strategy and tourism management. Ecosyst Health Sustain 5(1):124–132

Li R, Peng L, Deng W (2019) Resident Perceptions toward Tourism Development at a Large Scale. Sustainability 11:1–12

Lopes HDS, Remoaldo P, Ribeiro V (2019) Residents’ perceptions of tourism activity in a rural North-Eastern Portuguese community: a cluster analysis. Socio-economic Series, vol 46. Bulletin of Geography, pp 119–135

Lukman KM, Uchiyama Y, Quevedo JMD, Kohsaka R (2020) Local awareness as an instrument for management and conservation of seagrass ecosystem: Case of Berau Regency, Indonesia. Ocean and Coastal Management 203: 105451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105451

Lukman KM, Quevedo JMD, Kakinuma K, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R (2019) Indonesia Provincial Spatial Plans on mangroves in era of decentralization: Application of content analysis to 27 provinces and “blue carbon” as overlooked components. J For Res 24(6): 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/13416979.2019.1679328

Mazaya AFA, Yulianda F (2019) Taryono. Economic valuation of coral reef ecosystem for marine tourism in Karimunjawa National Park. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 241, 1–7

Mohee R, Mauthoor S, Bundhoo ZMA, Somaroo G, Soobhany N, Gunasee S (2015) Current status of solid waste management in small island developing states: A review. Waste Manage 43:539–549

Nelson KM, Partelow S, Schlüter A (2019) Nudging tourists to donate for conservation: Experimental evidence on soliciting voluntary contributions for coastal management. J Environ Manage 237:30–43

Ntuli H, Jagers SC, Linell A, Sjöstedt M, Muchapondwa E (2019) Factors influencing local communities’ perceptions towards conservation of transboundary wildlife resources: the case of the Great Limpopo Trans-frontier Conservation Area. Biodivers Conserv 28:2977–3003

Ollivaud P, Haxton P (2019) Making the most of tourism in Indonesia to promote sustainable regional development. OECD. 1–41

Pascoe S, Doshi A, Thébaud O, Thomas CR, Schuttenberg HZ, Heron SF, Setiasih N, Tan JCH, True J, Wallmo K, Loper C, Calgaro E (2014) Estimating the potential impact of entry fees for marine parks on dive tourism in South East Asia. Mar Policy 47:147–152

Prasetya JD, Ambariyanto, Supriharyono, Purwanti F (2018) Hierarchical Synthesis of Coastal Ecosystem Health Indicators at Karimunjawa National Marine Park. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 116, 1–7

Putro SS, Kosmaryandi N, Sunarminto T (2020) The Impact of Tourist Behaviors towards the Society Behavioral Change in Karimunjawa, Indonesia. JPIS 29(1):109–117

Qodriyatun SN (2018) Implementasi Kebijakan Pengembangan Pariwisata Berkelanjutan di Karimunjawa (Implementation of Sustainable Tourism Development Policies in Karimunjawa). Aspirasi 9(2):240–259 Bahasa

Quevedo JMD, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R (2020a) Perceptions of Local Communities on Mangrove Forests, their Services and Management: Implications for Eco-DRR and Blue Carbon Management for Eastern Samar, Philippines. J For Res 25(1):1–11

Quevedo JMD, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R (2020b) Perceptions of the seagrass ecosystems for the local communities of Eastern Samar, Philippines: Preliminary results and prospects of blue carbon services. Ocean Coast Manag 191:105181

Quevedo JMD, Uchiyama Y, Lukman KM, Kohsaka R (2021a) How Blue Carbon Ecosystems Are Perceived by Local Communities in the Coral Triangle: Comparative and Empirical Examinations in the Philippines and Indonesia. Sustainability 13(1):1–20

Quevedo JMD, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R (2021b) A blue carbon ecosystems qualitative assessment applying the DPSIR framework: Local perspectives of global benefits and contributions. Mar Policy 128:104462

Quevedo JMD, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R (2021c) Linking blue carbon ecosystems with sustainable tourism: Dichotomy of urban-rural local perspectives from the Philippines. Regional Studies in Marine Science 45:101820

Quevedo JMD, Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R (2021d) Local perceptions of blue carbon ecosystem infrastructures in Panay Island, Philippines. Coastal Engineering Journal. doi: 10/1080/21664250.2021.1888558.

Rana R, Singhal R (2015) Chi-square test and its application in hypothesis testing. Stat Pages 1(1):69–71

Santoso DH, Prasetya JD, Saputra DR (2020) Analisis Daya Dukung Lingkungan Hidup Berbasis Jasa Ekosistem Penyediaan Air Bersih di Pulau Karimunjawa. Jurnal Ilmu Lingkungan 18(2):290–296 Bahasa

Setiawan B, Rijanta R, Baiquni M (2017) Local Community Empowerment Through Vocational Training in Tourism on Karimunjawa Islands: Poor-Poor Tourism Approach. The 12th Biennial Conference of Hospitality and Tourism Industry in Asia. 10–13

Simbolon D, Irnawati R, Wiryawan B, Murdiyanto B, Nurani TW (2016) Fishing Zone in Karimunjawa National Park (Zona Penangkapan Ikan di Taman Nasional Karimunjawa). Jurnal Ilmu dan Teknologi Kelautan Tropis 8(1):129–143 Bahasa

Stefanica M, Butnaru GI (2015) Research on tourists’ perception of the relationship between tourism and environment. Procedia Econ Finance 20:595–600

Susanty A, Saptadi S (2020) Modelling the Causal Relationship among Variables that Influencing the Carbon Emission from Tourist Travel to Karimunjawa. IEEE 7th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications. 1039–1043

Susilo ES, Sugianto DN, Munasik, Nirwani, Suryono CA (2018) Seagrass Parameter Affect the Fish Assemblages in Karimunjawa Archipelago. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 116, 1–7

Sutawa GK (2012) Issues on Bali Tourism Development and Community Empowerment to Support Sustainable Tourism Development. Procedia Econ Finance 4:413–422

Taber KS (2017) The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res Sci Educ 48: 1273–1296

Tallei TE, Iskandar J, Runtuwene S, Filho WL (2013) Local Community-based Initiatives of Waste Management Activities on Bunaken Island in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Res J Environ Earth Sci 5(12):737–743

Tavakol M, Dennick R (2011) Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ 2:53–55

Tkaczynski A, Rundle-Thiele S, Truong VD (2020) Influencing tourists’ pro-environmental behaviours: A social marketing application. Tourism Manage Perspect 36:1–12

Tõnisson H, Kont A, Orviku K, Suursaar U, Rivis R, Palginõmm V (2019) Application of system approach framework for coastal zone management in Pärnu, SW Estonia. J Coast Conserv 23, 931–942 (2019)

Trialfhianty TI, Suadi (2017) The role of the community in supporting coral reef restoration in Pemuteran, Bali, Indonesia. J Coast Conserv 21:873–882

Uchiyama Y, Kohsaka R (2016) Cognitive value of tourism resources and their relationship with accessibility: A case of Noto region, Japan. Tourism Manage Perspect 19:61–68

Ugoni A, Walker BF (1995) The Chi Square Test An introduction. COMSIG Rev 4(3):61–64

Vargas-Sanchez A, Porras-Bueno N, Plaza-Mejia MDLA (2011) Explaining Residents’ Attitudes to Tourism Is a universal model possible? Annals of Tourism Research 38:460–480

Wibowo BA, Aditomo AB, Prihantoko KE (2018) Community Participation Of Coastal Area On Management Of National Park, Karimunjawa Island. IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 116, 1–7

WTO (2005) Making Tourism More Sustainable – A Guide for Policy Makers. eISBN: 978-92-844-0821-4. pp: 11–12

Yulianto I, Hammer C, Wiryawan B, Palm HW (2015) Fishing-induced groupers stock dynamics in Karimunjawa National Park, Indonesia. Fish Sci 81:417–432

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP16KK0053; JP17K02105; JP20K12398; 21K18456; JST and JICA - SATREPS project “Comprehensive Assessment and Conservation of Blue Carbon Ecosystem and Their Services in the Coral Triangle (Blue CARES)”; JST RISTEX Grant Number JPMJRX20B3; JST Grant Number JPMJPF2110; Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research Grant Number CBA2020-05SY-Kohsaka; Kurita Water and Environment Foundation [20C002]; Toyota Foundation (D17-N-0107); and Foundation for Environmental Conservation Measures, Keidanren (2020); Heiwa Nakajima Foundation (2022); Asahi Group Foundation (2022); JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), 2022-2025 (Balancing Tourism and Conservation in Era of Climate Change and Shrinkage: Land Use Maps as a Boundary Object).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lukman, K.M., Uchiyama, Y., Quevedo, J.D. et al. Tourism impacts on small island ecosystems: public perceptions from Karimunjawa Island, Indonesia. J Coast Conserv 26, 14 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-022-00852-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-022-00852-9