Abstract

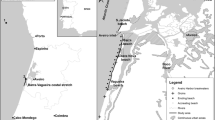

In Sri Lanka, the total demand for sand is about 12,000,000 m3 per year with a demand growth projected to increase by 10 % every year. However, Sri Lanka’s construction industry seems to face a shortage of sand if offshore sand mining is not promoted as a viable alternative and over-exploitation of river sand may lead to more significant damage to rivers (which is presently a serious issue). This article discusses the suitability or otherwise of the unexplored south-eastern, east and north-western offshore areas for exploration and mining works. This study was conducted by consulting several government organizations and universities dealing with coastal resources management, literature reviews and Key Informants’ Interviews held with Fisher Folk Societies and Divers’ Organizations in the study areas. The east and north-western offshore locations are not ideal considering the bathymetry (most locations in the east coast have water depths >20 m, hence mining is not commercially viable; in the north-western offshore areas depth is <15 m; mining is prohibited in Sri Lanka at depths ≤15 m and <2 km offshore) and the occurrence of critical habitats. In the south-eastern offshore areas the complex wave climate resulting in significant coastal/shoreline stability variations is a concern and the sea is very deep (>20 m beyond 2 km offshore). Therefore, by considering the views expressed by the Divers’ Organizations and Fisher Folk societies it would be ideal to undertake exploration studies in the offshore areas in the north-eastern stretch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Borrow area is about 10–11 km away from Colombo (capital city of Sri Lanka)

Formerly the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy was known as the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources

NARA is the research institution under the Ministry of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources

Quarry dust and manufactured sand have been considered as alternatives to river sand to be used in concrete. Quarry dust has been reported to increase the strength of concrete over concrete made with equal quantities of river sand, though it causes a reduction in the workability of concrete (Sukesh et al. 2013)

FMAs are declared under the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act No. 2 of 1996 (which is administered by the Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources). Great and Little Basses were declared as FMAs in 2001 (Perera and de Vos 2007)

Gulf of Mannar cluster (which includes the Palk Bay–Mannar Island–Adams Bridge–Dhanuskodi–Rameshwaram of Sri Lanka and India) is the other site that is identified as a ‘High Regional Priority Area’ under the IUCN/NOAA project on “World Heritage Biodiversity”

CCD comes under the Ministry of Defense and Urban Development and recently, the CCD was renamed as the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Department

Generally, the GSMB issues 3 types of IML namely IML/A, IML/B and IML/C

There are 3 Categories known as TDL/A, TDL/B and TDL/C. Note that TDL/C is applicable to trade in bricks and lime produced manually. However, TDL/A would be needed if offshore sand is to be exported and TDL/B would be needed if offshore sand is to be sold locally.

NEA is the main National Legislation in Sri Lanka enforced by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) under the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy to regulate all activities that affect the environment

Formerly the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy was known as the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources

References

Attenborough D (1979) Life of earth: a natural history. William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd, London

Banister K, Campbell A (1985) The encyclopedia of underwater life. George Allen & Unwin, London

Central Environmental Authority (2005) Environmental atlas of Sri Lanka. Central Environmental Authority, Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Sri Lanka

Couper AD (1983) The times atlas of the oceans. Times Books Limited, London

Dias WPS, Nanayakkara SMA, Seneviratne GAPSN, Nanthanan T (2002) Properties of concrete and plaster using offshore sand, manufactured sand and quarry dust. Lanka Ready mix Concrete Association

Dias WPS, Seneviratne GAPSN, Nanayakkara SMA (2008) Offshore sand for reinforced concrete. Constr Build Mater 22:1377–1384

Dolage DAR, Dias MGS, Ariyawansa CT (2013) Offshore sand as a fine aggregate for construction industry. Br J Appl Sci Technol 34:813–825

EML Consultants (2011) Strategic environmental assessment of the Cauvery Basin. Petroleum Resources Development Secretariat, Ministry of Petroleum and Petroleum Resources Development, Sri Lanka and EML Consultants

ERM (2002) Environmental impact assessment study for the off-shore sand mining–MahaOya-Lansigama Area. Environmental Resources Management

Gunaratna PP, Ranasinghe DPL, Sugandika TAN (2011) Assessment of nearshore wave climate off the Southern Coast of Sri Lanka. Engineer XXXXIV:33–42

Hettiarachchi S, Samarawickrama S, Ratnasooriya H (2011) Kirinda fishery harbour rehabilitation. Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka

Hilton MJ (1994) Applying the principle of sustainability to coastal sand mining: the case of Pakiri-Mangawhai Beach, New Zealand. Environ Manag 6:815–829

Hommes S, Hulscher SJMH, Stolk A (2007) Parallel modeling approach to assess morphological impacts of offshore sand extraction. J Coast Res 23:1565–1579

Jinadasa SUP, Rajapaksha JK (2007) Sedimentological status of some surficial sediments in Gulf of Mannar, Sri Lanka. J Natl Aquat Resour Res Dev Agency 38:25–32

Joseph L (2013) National report of Sri Lanka on the formulation of a transboundary diagnostic analysis and strategic action plan for the Bay of Bengal large marine ecosystem programme. BOBLMEP/National Report, Sri Lanka. http://www.boblme.org/documentRepository/Nat_Sri_Lanka.pdf. Accessed 08 Jan 2013

Miththapala S (2008) Coral reefs. Coastal ecosystems series (vol 1). Ecosystems and Livelihoods Group Asia, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Sri Lanka

Netherlands Economic Institute (1992) National sand study for Sri Lanka (volumes 1 and 2). Netherlands Economic Institute, Delft

Perera N, de Vos A (2007) Marine protected areas in Sri Lanka: a review. Environ Manag 40:727–738

Rajasuriya A (2007) Coral reefs in the Palk Strait and Palk Bay in 2005. J Natl Aquat Resour Res Dev Agency 38:77–86

Rajasuriya A, White AT (1995) Coral reefs of Sri Lanka: review of their extent, condition and management status. Coast Manag 23:70–90

Sri Lanka Water Partnership (2008) River sand mining–boon or bane? A synopsis of a series of national, provincial and local level dialogues on unregulated/illicit river sand mining. Sri Lanka Water Partnership

Sukesh C, Krishna KB, Teja PSLS, Rao SK (2013) Partial replacement of sand with quarry dust in concrete. Int J Innov Technol Explor Eng 2:254–258

Survey Department of Sri Lanka (2007) The national atlas of Sri Lanka, 2nd Edition. Survey Department of Sri Lanka

Acknowledgments

The work reported in this article is a case study undertaken for One Chwee Ling (Pte) Ltd, Singapore.

I wish to thank the various government agencies and universities mentioned in this report for their value support. Very special thanks are given to Mr. Priyantha Jinadasa (Research Officer, National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency) and Prof. Saman Samarawickrama (University of Moratuwa) for providing some important reports. I also thank the Diving Instructors, Heads of the Fisher folk societies and all other interviewees (fishermen and divers) for spending their valuable time out of busy schedules to support this study. In this respect very special thanks are given to Mr. R.K. Somadasa de Silva (Director, International Diving Center PVT Ltd) and Mr. B. Dayarathne (Naturalist, Nature Trails, Chaaya Blu Hotel) for their voluntary assistance rendered to me.

Useful comments and suggestions given by Dr. David Richard Green (Chief Editor of this journal) and the anonymous reviewers further improved this manuscript. Mr. D.M.S. Atugoda (EML Consultants PVT Limited) proofread the revised manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1 Legislation in Sri Lanka for offshore sand mining

Acts and laws

Under the Mines and Minerals Act No. 33 of 1992, the GSMB issues four types of licenses with reference to offshore sand deposits namely exploration, mining, trading and transport.

-

An Exploration License which grants the license-holder the exclusive right to explore for all mineral categories authorized by the license. Initially, the GSMB issues Exploration Licenses only. Exploration Licenses are issued to undertake exploration studies at a distance of 2 km or more than 2 km seawards from the mean low water line. This is not specified under the Mines and Minerals Act No. 33 of 1992. However, the GSMB has decided on this taking into consideration that removal of sand is prohibited by the Coast Conservation Department (CCD)Footnote 7 within the Coastal Zone (see below).

-

An Industrial Mining License (IML)Footnote 8 which grants exclusive rights to explore for, mine, process and trade in all minerals mined within the area specified in such license.. An IML/A is issued where the production volume would be more than 1,500 m3 per month. However, issuing of an IML/A license is subjected to approval of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report submitted (see below) by the Project Proponent. The validity period of the license is determined by the GSMB.

-

A Trading License (TDL)Footnote 9 which shall grant the non-exclusive right to purchase, store, process, trade in and with the special authorization of the Director-General, to export minerals in respect of which the license is issued.

-

A Transport License to transport minerals or mineral-bearing substances shall be issued for such quantity and period and for such minerals as may be specified in such license. All exploration, mining and trading license-holders shall require a transport license to transport minerals or mineral-bearing substances.

The clause 65(2) of Mines and Mineral Act No 33 of 1992–“Restriction on the power to mine the sea bed” states “No person other than a person holding a license in that behalf issued under the Mining and Minerals Act No 33 of 1992, shall mine the sea bed”.

All mining and mineral extraction projects (including all offshore mining and extraction works) are prescribed projects as contained in Gazette (Extraordinary) No 772/22 of 24 June 1993 and No 859/14 of 23 February 1995. Therefore, according to Section 23 (z) of the National Environment Act (NEA) No. 47 of 1980Footnote 10 (as amended/Act No. 56 of 1988 and Act No. 53 of 2000) such projects (whether located wholly or partly outside the coastal zone as defined by the Coast Conservation Act No. 57 of 1981, now known as the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act No. 57 of 1981) requires an EIA study in order to obtain the Environmental Clearance/Approval from the Central Environmental Authority (CEA). CEA is the Project Approving Agency (PAA) and the main government body in Sri Lanka under the Ministry of Environment and Renewable EnergyFootnote 11 that has been entrusted with responsibilities regarding the use of lands, environmental management and conservation of natural resources, etc. (except in the North-Western ProvinceFootnote 12 where the Provincial Environmental Authority enforces the North Western Province Environmental Statute No. 12 of 1990). A mining license is issued by the GSMB only if the EIA submitted is approved by the CEA in the form of an Environmental Clearance/Approval. It should be noted that the CEA also considers the recommendations made by the CCD when issuing the Environmental Clearance/Approval.

Any requirements with reference to offshore sand exploration and mining have not been prescribed in the Coast Conservation Act No. 57 of 1981 and its amendments (including the latest amendment known as the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act No. 57 of 1981) which are administered by the Coast Conservation Department (CCD) as mandated. According to several reports (Netherlands Economic Institute 1992; ERM 2002), following conditions have to be adhered to with reference to offshore mining.

-

CCD requires the Project Proponent to carry out investigations and submit the CCD for permit evaluation.

-

CCD does not permit mining within 5 fathom contours (i.e., 9.1 m depth) or 1,000 m seawards from the low water mark, whichever is furthest.

-

Where corals or sandstone reef occurs, no permission is granted in areas occurring between reefs and shore and the CCD specifies the minimum distance between mining site and nearest reef.

-

Mining is restricted to a depth normally determined by the CCD for the particular site.

-

Mining methods, stockpiling of mined sand, transferring methods from mining site to storage areas, storage sites and disposal sites will be specified by the CCD.

However, very recently for regulation purposes the CCD decided that mining will not be permitted in areas where depth is ≤15 m and at a distance is <2 km from the coastline (low water mark) and only 1.5 m layer of sand could be removed.

Nevertheless, within the Coastal Zone (see Fig. 12 below) as per the Coast Conservation Act No. 57 of 1981 and its amendments any removal of corals other than for research purposes, removal of sand (except in areas identified by CCD) and any development activity within sand dune areas are prohibited. Coastal Zone (see Fig. 12 below) is defined in the Coast Conservation Act No. 57 of 1981 and its amendment Act No. 64 of 1988 as “the area lying within a limit of 300 m landward of the Mean High water Line and a limit of 2 km seaward of the mean Low Water Line and in the case of rivers, streams lagoons or any other body of water connected to the sea either permanently or periodically, the landward boundary shall extend to a limit of 2 km measured perpendicular to the straight base line drawn between the natural entrance points identified by the mean low water line thereof and shall include waters of such rivers, streams, and lagoons or any other body of water so connected to the sea”.

As per the Section 22(A) on “Application of the Mines and Minerals Act” under Part III (Permit Procedure) of the recently amended Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act No. 57 of 1981 (as amended by Act No. 64 of 1988, No. 49 of 2011 and by the Mines and Mineral Act No. 33 of 1992), prior consent should be obtained from the Director-General (DG) of the CCD in relation to an area lying within the Coastal Zone for mining works. Without such prior consent, the Director-General of the GSMB will not issue any permit. Where the Director-General (DG) of the CCD consents to the grant of a permit by the Director-General of the GSMB, DG of the CCD may require that such conditions as he deems necessary in the circumstances be attached to the permit so granted. As per subsection (4) of Section 22A, the GSMB reserves the right to cancel any permit (after consultation with the DG of the CCD) if the permit holder fails to comply with the permit conditions and any directions given by the GSMB (with the advice of the CCD) within a specified period. According to subsection (5) of Section 22A, “Where a permit is cancelled in terms of subsection (4) the provision of Sections 38, 39 and 40 of the Mines and Minerals Act No. 33 of 1992, shall mutatis mutandis apply in respect of such cancellation”.

Appendix 2 Questionnaire for the divers’ organizations

Date:

Venue:

Name & Designation:

Organization & Address:

-

Is there a specific season that the divers go to the sea? If yes, why and time period?

-

What is the minimum distance they dive and depth? Why?

-

Is there any sand available in areas they dive (give GPS points if available) and what is the extent/area of the sand deposits or quantity?

-

How do these deposits vary with the seasons (considering wave climate/season)?

-

Are these deposits similar or different to beach and dune sands in terms of color and fineness/grading?

-

Are these deposits rich in chlorides/salt?

-

Are there are any places of accretion? If yes, where and GPS points. How often there is accretion (describe in terms of seasons)?

-

Any remarks?

Appendix 3 Questionnaire for fisher folk societies

Date:

Venue:

Name & Designation:

Organization & Address:

-

Is there a specific season the fisher folk groups go to the sea? If yes, why and time period?

-

What is the minimum distance boats travel and anchor the boats away from the coastline?

-

How deep or shallow is the area where the boats are anchored? Provide the GPS points (if available). Are there any deposits found in such areas? Provide the GPS points

-

What is the extent/area of the sand deposits or quantity?

-

How do these deposits vary with the seasons (considering wave climate/season)?

-

Are these deposits similar or different to beach and dune sands in terms of color and fineness/grading?

-

Are these deposits rich in chlorides/salt?

-

Are there are any places of accretion? If yes, where and GPS points. How often there is accretion (describe in terms of seasons)?

-

Any remarks?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kularatne, R.K.A. Suitability of the coastal waters of Sri Lanka for offshore sand mining: a case study on environmental considerations. J Coast Conserv 18, 227–247 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-014-0310-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-014-0310-7