Abstract

In today's competitive landscape, startups and large corporations increasingly acknowledge the mutual benefits of collaboration. Despite the apparent benefits, collaborations come with their own set of challenges that may affect their success. This research delves into the dynamics of collaborations between startups and large corporations, assuming the startup’s perspective. It aims to explore the paradoxical tensions arising from this asymmetrical relationship and how they impact the sustainability performance of startups. It further investigates how startups manage the pressures of large corporations to prioritise short-term gains over long-term sustainability goals, examining the role of ambidexterity in maintaining a commitment to sustainability when facing these challenges. Through a survey conducted among 189 Born-Sustainable Italian startups engaged in open innovation initiatives with large corporations, this paper seeks to uncover how these pressures influence startups' ability to achieve sustainable performance and balance immediate performance expectations with long-term sustainability goals. The findings are expected to contribute to a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that enable startups to navigate the complexities of collaborations, enhancing innovation, resilience, and sustainability performance, thus fostering a more collaborative and productive partnership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, innovative startups have become pivotal in driving economic growth, creating jobs, and generating wealth (Klein et al. 2019; Kaczam et al. 2022). Characterized by their agility, flexibility, and bold approach to risk-taking, these companies strive for breakthrough innovations and sustainable business models (Corvello et al. 2023). Their efforts are increasingly acknowledged for addressing global sustainability challenges, marking a significant contribution to the wider societal and environmental goals (Voinea et al. 2019).

The unique characteristics of startups have attracted the attention of various stakeholders, particularly large corporations. These established entities see collaborations with startups as an opportunity to infuse their operations with renewed dynamism and innovative capabilities (Rigtering and Behrens 2021). Likewise, startups recognise the potential benefits of collaborating with larger corporations. In fact, despite their innovative potential, startups frequently encounter financial and material resource shortages. This is where large corporations play a crucial role, offering startups access to essential resources—financial backing, research facilities, market insights, and connections with potential customers (Prashantham and Kumar 2019).

The interplay between established corporations and emerging startups is a critical area of modern business dynamics (Chesbrough 2017). The collaboration represents a symbiotic relationship that is increasingly recognized as a catalyst for innovation, economic growth, and technological advancement (Hora et al. 2018). The fusion of these distinct yet complementary strengths presents a unique opportunity for mutual growth and the acceleration of technological development (Corvello et al. 2023).

The recognition of mutual benefits has recently encouraged both startups and large companies to initiate collaborative programs on open innovation initiatives (Steiber et al. 2020). From a theoretical perspective, collaboration among startups and corporations can be situated within the inter-organizational partnership framework (Williamson 1991). However, as stated by Allmendinger & Berger (2020), these collaborations are notably asymmetrical: collaboration partners have diverse maturity and size (Corvello et al. 2024a) and relationships are often characterized by tension due to the significant differences in culture, resources and objectives (Prashantham and Kumar 2019).

These differences make collaborations particularly challenging for each party involved. Despite the enthusiasm surrounding the above-mentioned advantages, some factors inhibit collaboration. Startups fear opportunistic behaviour by large firms, particularly the exploitation of their knowledge and technologies for short-term goals (Bereczki 2019). Conversely, large companies worry that startups' inexperience might lead to premature failures of these initiatives (Hora et al. 2018).

This dynamic highlights the complex interplay of cooperation and competition that define, and at times challenge, the relationships between startups and large corporations in the landscape of open innovation. Moreover, innovation-focused collaborations allow both parties, startups and large companies, to benefit from external knowledge and capabilities, thereby enhancing innovative capabilities while seeking to secure a competitive advantage. It is widely recognized that The heterogeneity of characteristics exhibited by startups and established firms has a substantial impact on performance (Halberstadt et al. 2021). However, the asymmetry that characterises such collaborations is also manifested in the fact that large companies benefit more rapidly from collaborations than startups.

This gap stems from what has been referred to by several scholars (e.g. Akinremi and Roper 2021) as the collaboration paradox. This paradox stems from the fact that startups, unlike large companies, lack the internal resources and capabilities to effectively appropriate the benefits of collaboration. Simply put, the paradox highlights a discrepancy between the potential benefits that a collaboration can provide and the perceived obstacles for startups to effectively implement it.

The simultaneous presence of contrasting forces or principles that, while seemingly in conflict, actually contribute to the effectiveness and success of the collaboration. The literature refers to it under the concept of paradoxical tension (Remneland Wikhamn 2020). Such a tension arises from the conflicting yet complementary needs, goals, and practices between large corporations and startups engaged in open innovation. In the context of an innovative collaboration between a large company and a startup, the paradoxical tensions that arise depend upon the inherently different nature of the two parties involved. On the one hand, large companies contribute with a consolidated market presence, numerous and diversified resources and structured processes (Bronnenmayer et al. 2016). On the other hand, startups are characterised by flexibility, agility, an innovative mindset and greater risk tolerance (Margherita et al. 2020). This collaboration, although beneficial to both organisations in different ways, creates fertile ground for paradoxical tensions to arise, where disparities in resources and objectives can both hinder and strengthen the innovative potential of the partnership.

The complexity increases when focusing on startups that prioritize sustainability (Deyanova et al. 2022). Startups are increasingly aware that a focus on sustainability is particularly crucial as it aligns their growth trajectories with broader societal expectations, ensuring long-term viability and success. Achieving high sustainability performance allows startups to differentiate themselves in competitive markets, meet the growing consumer demand for responsible business practices, and comply with stringent environmental regulations. Furthermore, sustainability practices can lead to operational efficiencies, reduce waste and energy consumption, and open up new market opportunities (Kraus et al. 2020a, b).

However, the involvement of big corporations in collaborations with startups, while providing essential resources and market access, also exerts considerable pressure (Nylund et al. 2021) that potentially diverts focus from sustainability performance. This pressure often manifests in the form of demands for rapid scaling, efficiency, and immediate financial returns. Startups, striving to transform from entrepreneurial ventures into viable businesses, might find themselves prioritizing short-term gains and operational scalability over long-term sustainability goals (Schaltegger and Wagner 2011).

This shift in focus can lead to compromises in environmental standards, social responsibility, and ethical business practices. For startups, navigating these tensions involves balancing the pressure to meet corporate partners' immediate performance expectations with the imperative to adhere to sustainability goals. The ability of startups to simultaneously explore new opportunities and exploit existing capabilities becomes crucial in the context of asymmetric collaborations and paradoxical tensions. Ambidextrous startups are better positioned to navigate the pressures exerted by large corporate partners while maintaining their commitment to sustainability. This dual capability enables startups to innovate and adapt swiftly, turning constraints into catalysts for growth and sustainability (O'Reilly and Tushman 2013).

The successful management of these tensions can lead to enhanced innovation, resilience, and sustainability performance, as startups learn to integrate diverse perspectives and capabilities in their strategic approach (Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009). Recognizing and embracing these paradoxical tensions as opportunities rather than obstacles fosters a more collaborative and productive partnership, ultimately contributing to the sustainable growth of both parties.

In short, startups may face a twofold challenge when involved in collaboration with big corporations. They are required to foster economic efficiency and effectiveness (Jagani and Hong 2022), as well as uphold sustainability in terms of environmental and social responsibilities (Bocken 2015). Nonetheless, these goals may not always coincide, leading to a scenario where competitive forces could promote practices that are not sustainable, or conversely (Venkobarao 2019).

Previous studies on the topic have mainly focused on the dynamics of collaboration between start-ups and established companies. Research like that of Ching and Caetano (2021) has examined the reasons behind such partnerships, outlining a wide range of motivations ranging from the pursuit of innovation to integration into a broader ecosystem.

Other works (e.g. Dizdarevic et al. 2023; Steiber and Alänge 2021), explored patterns of collaboration between companies and start-ups and their effects on business strategies. Corvello et al. (2024a) extended this discussion by examining the economic and technological performance of these collaborations. However, a common theme seen in previous studies is the tendency to adopt the perspective of the large firm, often underestimating the startup viewpoint (Weiblen and Chesbrough 2015; Rigtering and Behrens 2021; Steiber and Alänge 2021).

There is a significant gap in the understanding of the sustainability dimension applied to collaborations between start-ups and large companies within innovation ecosystems, especially in terms of the pressures on sustainable performance and the importance of navigating paradoxical tension to balance short-term and long-term objectives in asymmetrical collaborations. Hence, this article aims to address the following research question:

RQ1: How do collaborations with large corporations impact the sustainable performance of startups, and what strategies enable startups to balance immediate operational demands with long-term sustainability goals?

This study seeks to bridge the existing gap in the literature by examining the influence of large corporations on the sustainable performance of startups within the framework of asymmetrical collaborations and paradoxical tensions. Specifically, it investigates the dual challenge startups face in achieving economic efficiency and upholding sustainability amidst the pressures exerted by their corporate partners. By surveying 189 Born-sustainable Italian startups engaged in open innovation initiatives with large corporations, the research aims to elucidate the mechanisms through which startups navigate these complex dynamics.

The urgency of this research stems from the pressing need to understand these dynamics, which are critical for startups to succeed sustainably in an increasingly competitive global environment. This contribution is vital for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers interested in fostering sustainable growth and innovation within the startup ecosystem (Fernandes and Ferreira 2022). Indeed, the anticipated findings are expected to contribute significantly to our understanding of the interplay between economic pressures and sustainability goals, offering insights into strategies that enable startups to thrive in partnerships. Furthermore, our results contribute to advancing the academic knowledge in the field by exploring the sustainable performance impacts of asymmetrical collaborations between startups and large corporation, a perspective not deeply addressed in current literature.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses development

2.1 Interorganizational collaboration between sustainable-oriented organizations

Interorganizational collaboration refers to the process in which two or more organizations pool their strengths to achieve a shared goal or address a common challenge. This type of collaboration involves the sharing of knowledge, resources and capabilities to create synergies that benefit all parties involved, leading to the achievement of goals that would be difficult or impossible for a single organization to attain (Wilkinson and Young 2002; Sharma and Kearins 2011). In the literature, interorganizational collaboration can be classified according to its orientation along the supply chain (vertical vs. horizontal) or externally oriented. In the former case, it is called vertical collaboration when it occurs between entities operating at different levels of the supply chain, while it is called horizontal collaboration when the collaborating entities occupy the same position in the supply chain.

External collaboration, on the other hand, does not involve organizations located along the supply chain, but concerns collaborations with actors outside it (e.g., universities, research bodies, governments, institutions, etc.) (Walker et al. 2021). In this context, startups, suffering from the liabilities of smallness and newness (Gimenez-Fernandez et al. 2020), are ideal candidates to take part in inter-organizational collaboration processes. The scarcity of assets, financial limitations, and intensifying competitive landscapes often forces startups to seek external partners who can provide support during the development and commercialization phases of their ideas (Usman and Vanhaverbeke 2017).

Among collaboration partner options, the choice often falls to large companies due to the potential benefits they can reap (Primario et al. 2024). Partnering with large companies affords startups access to complementary resources, assets and expertise, as well as financial backing and experience in the large company's industry, along with an established customer base and distribution channels (Giglio et al. 2023).

In addition, the large company acts as a sponsor for the startup to potential investors, helping it overcome problems related to its novelty and perceived financial unreliability (Gutmann & Lang 2022). At the same time, large companies are increasingly keen to initiate collaborations with startups, seeing more and more potential in them. Motivations for large companies to initiate collaborations with startups include breaking inertia by disrupting current organisational practices (Steiber et al. 2020), bringing fresh perspectives and an agile problem-solving approach (Gutmann and Lang 2022) or gaining access to new technologies (Jackson and Steiber 2019).

This phenomenon becomes more pronounced and intense when startups are "born sustainable" (i.e. “originally conceived to develop a new business model leveraging sustainability at its core” Todeschini et al. 2017, p. 765) or aim to integrate sustainability practices into their business models or operational strategies (i.e., oriented toward sustainability). An increasing number of companies are now committing to sustainability goals by boosting their investments (Corallo et al. 2023; Crapa et al. 2024).

In these cases, a partnership between a startup and a large company that also prioritizes sustainability occurs with even more probability. For the startup, collaborating with a company guarantees benefits not only in terms of sustainability but also competitiveness, while for the large corporation, a significant margin of benefit exists, making the collaboration highly attractive. Although each collaboration is mutually advantageous for the involved parties, when it comes to achieving sustainability goals, these benefits become even more pronounced (Audretsch et al. 2024). Indeed, as highlighted by Glasbergen et al., (2007), integrating sustainability into an organization poses a challenge for any entity, necessitating a multidisciplinary approach and expertise.

The scholarly literature emphasizes that it is uncommon for organizations, even large corporations, to independently enjoy all the necessary skills and resources for such initiatives, thereby underlining the crucial role of collaboration (Sharma & Kearins 2011; Castellani et al. 2024).

Interorganizational collaboration between startups and large companies, particularly those focusing on sustainability, is a critical area of study in collaborative innovation and sustainable development. However, as the relationship between these two entities is asymmetrical, the unique resources and capabilities of big corporations can significantly influence the strategic direction and operational capabilities of new ventures (Volkmann et al. 2021; Giglio et al. 2023). A new venture's commitment to sustainability and the subsequent decisions it makes in this direction is driven by the resources and competencies available (Amankwah-Amoah et al. 2019). Large companies actively engaged in corporate sustainability can provide both the resources and strategic frameworks that encourage startups to reinforce sustainable goals within their business models (Cacciolatti et al. 2020).

Thus, we formulated the following hypothesis:

-

H1: The sustainable orientation of big corporations positively influences the sustainability goals of collaborating startups.

For startups, a focus on sustainability is inseparable from the pursuit of growth outcomes, as scalability is a prerequisite for success. This is true for both traditional and "born sustainable" startups, where economic outcomes are closely intertwined with social and environmental outcomes. From the natural resource-based view, as proposed by Hart (1995), it is indeed possible for an organization to operate sustainably and still achieve excellent performance. Contrary to the idea that sustainability practices can hinder an organization's growth, this approach suggests that such practices act as performance catalysts. It is argued that adopting initiatives to create environmental and social value not only increases a company's efficiency but also significantly heightens its competitive advantage. In fact, several scholars, such as Bocken (2015) and Cacciolatti et al. (2020) have highlighted the strong influence of sustainability goals pursued by startups on their sustainability performance.

The identification of clear sustainability goals encourages startups to innovate in ways that improve resource efficiency, which can reduce costs and enhance environmental performance (Di Vaio et al. 2022). As market demand shifts towards more environmentally-friendly and socially-responsible products, startups with strong sustainability goals gain a competitive edge and attract a growing segment of conscientious consumers (Kraus et al. 2020a, b). Setting sustainability targets practically means integrating startups’ business strategies and operations with triple bottom-line principles (Elkington 1998), thus enhancing their sustainability performances.

Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

-

H2: Startups’ sustainability goals positively impact their sustainability performance.

2.2 Paradoxical tension arising in inter-organizational collaborations

Despite the potential advantages for both startups and big corporations, the asymmetry that characterizes their collaboration may pose a significant challenge to their success (Ten Buuren 2017; Aaboen and Aarikka-Stenroos 2017; Chappert et al. 2024). Although collaboration has the potential to create superior outcomes with respect to purely competitive relationships, many collaboration fail to deliver the intended results due to its paradoxical nature (Gernsheimer et al. 2024). As Emden et al. (2006) point out, for the success of innovative collaboration, such as those found in Open Innovation contexts, mere complementarity of resources among participants is not enough. Instead, technological, strategic and relational alignment is needed. While technological alignment and fostering relational harmony are relatively straightforward, achieving strategic one poses a significant challenge in partnerships between startups and established companies due to organizational disparities. Indeed, strategic alignment requires that the motivations for collaboration and the goals set by both entities are not only aligned but also noncompetitive.

As for the collaborations between startups and large companies, where different organizational structures and cultures can lead to conflicting goals and motivations, it becomes particularly hard to reach. Startups look for partnerships for innovation with established firms to mitigate the potential negative consequences of being new and small (Spender et al. 2017). In contrast, established firms typically aim to leverage startups' proprietary technologies or innovations to gain competitive advantage and market power, thus using startups as catalysts to boost their innovation efforts (De Groote and Backmann 2020). The occurrence of seemingly opposing but complementary forces within a collaborative effort has been identified in the literature as paradoxical tension (Remneland Wikhamn 2020).

As a result, organizational asymmetry turns into power asymmetry, understood as the unequal distribution of influence or control between two business entities involved in a collaborative relationship. This imbalance occurs when one party (i.e. the big corporation) holds more power than the other (i.e. the startup), thereby significantly influencing the decisions, operations, and outcomes of the collaboration (Hao and Feng 2018). The presence of power asymmetry might lead to opportunistic actions or enable the more powerful entity to secure a larger share of the relationship's benefits (Nyaga et al. 2013). As a result, the concept of power asymmetry acquires the connotation of pressure exerted by big corporations on the startup, which may cause further divergence in their goals, reinforcing the emergence of paradoxical tensions.

Hence the following hypothesis:

-

H3: The pressure perceived by startups from big corporations is positively related to the degree of paradoxical tension experienced in the collaboration.

According to the paradox perspective, the term paradoxes refers to "contradictory yet interrelated elements” (Smith & Lewis 2011 p. 389) present in inter-organizational collaborations, such as that between a startup and a big corporation, regardless of whether the actors involved are aware of them (Papachroni et al. 2016). Trust and opportunism have a joint effect on sustainable-oriented collaboration. Adopting a strategy that embraces paradoxes can foster synergies that enhance the management of inter-firm relationships and contribute to obtain high performance (Blome et al. 2023).

In the literature, paradoxical tensions of inter-organizational relationships involve multiple aspects (Fortes et al. 2023), such as long-term vs short-term orientations (e.g. (Chou and Zolkiewski 2018), coopetition (Runge et al. 2022), exploration vs exploitation (Rey-Garcia et al. 2021)or goal congruence vs goal divergence (Galati et al. 2021). Fortes et al. (2023) highlight how paradoxical tensions occur in two consecutive phases in inter-organizational collaborations, referred to as “pre-tension” and “post-tension”.

The pre-tension phase is characterized by a slightly conflicting relationship between the two entities, while the post-tension phase reveals the negative consequences of such manifest or latent conflict. These outcomes manifest as poor performance of one of the entities involved, typically the startup. The level of complexity increases when the startup involved has a sustainability orientation, pursuing sustainable performance (Deyanova et al. 2022). In such cases, the big corporation may exert its power to divert the startup's focus from sustainability, negatively impacting its sustainable performance (Nylund et al. 2021). Thus, paradoxical tensions, if not effectively managed, can hinder the ability of startups to achieve their sustainability performances, as the pressures may lead to prioritizing short-term gains over long-term sustainability commitments.

Hence the following hypothesis has been formulated:

-

H4: Paradoxical tension negatively impacts the sustainability performance of startups.

2.3 Ambidexterity

The power asymmetry and the resulting pressure exerted by large corporations on startups force an organizational response from the latter to balance the demand for short-term performances from the former with the startup’s willingness to achieve sustainability. Scholarly work points to ambidexterity as a viable strategy to resolve this misalignment (Feng et al. 2019; Galkina et al. 2022). Startups' ambidexterity refers to the ability to effectively integrate and balance two conflicting aspects: the exploration of new opportunities and the exploitation of existing capabilities (Balboni et al. 2019; Rojas-Córdova et al. 2023).

This dual approach enables startups to survive in a competitive environment by adapting quickly to change and making the most of the resources at their disposal (Utomo and Kurniasari 2023). Accepting and managing the inherent complexity becomes a crucial factor to achieve ambidexterity (Schindler et al. 2024). In asymmetrical inter-organizational relationships, where a big corporation exerts considerable pressure on the startup, the latter is compelled to develop ambidexterity not to give up on the achievement of its sustainability goals.

Developing ambidexterity allows us to simultaneously pursue divergent goals, arising from the conflicting interests of the parties involved. Given the power asymmetry between startups and large corporations, unsuccessful management of such conflicts would penalize the startup, overwhelmed by the firm’s pressure and unable to scale (Hao and Feng 2018Being ambidextrous means transforming divergences and constraints into opportunities for growth. Balboni et al. (2019) highlight that ambidexterity is often necessary to adapt, survive, and scale in dynamic and complex contexts.

For these reasons, we posit:

-

H5: The pressure exerted by a large corporation on the startup positively influences the startup's ambidexterity.

According to ambidexterity theory, organizations can achieve superior performance by simultaneously addressing and integrating opposing but complementary demands. Research suggests that firms engaged in both the exploration of new opportunities and the exploitation of existing competencies through a balanced approach are likely to outperform those that focus on only one aspect (Junni et al. 2013). This view, drawing on March's (1991) study, emphasizes how important such a balanced approach is to achieving both short-term and long-term goals. Ambidexterity is widely recognized as a source for achieving higher levels of firm performance (Khursheed and Mustafa 2024). As for born-sustainable or sustainability-oriented startups, the concept of ambidexterity can contribute to the achievement of sustainability performance. As stated by (Yu and Zhu 2022), pursuing sustainability goals means pursuing economic, social and environmental goals at the same time, adhering to the "triple bottom line" principle (Elkington 1998). However, initiatives in the direction of social and environmental improvements are often perceived as detrimental to profits, giving rise to a fervent academic debate concerning the tension between economic prosperity and the pursuit of sustainability goals (Harangozo et al. 2018).

In the context of startups, entities that by definition are growth-oriented, this debate could take on the connotations of a real conflict, trapping them in a situation of inertia and immobility in which they fear that the pursuit of sustainability goals will limit their growth potential (Hoogendoorn et al. 2019). In this regard, being ambidextrous represents a capability that enables the startup to solve this struggle and break out of the impasse. It ensures the ability to embrace divergent goals of whatever nature they may be, thus including environmental, social and economic ones (Ciasullo et al. 2020).

Identifying effective and stable strategies to navigate the complexities of a cooperative-based approach is crucial for the long-term success and sustainability of these organizations (Sánchez-Robles et al. 2023). Startup ambidexterity promotes sustainability performance of these startups by ensuring that they can effectively balance the management of opposing goals, such as organic growth and sustainability(Fortes et al. 2023). In addition, ambidexterity encourages companies to explore new market opportunities related to sustainability while at the same time leveraging existing resources to optimize environmental social and economic performance simultaneously.

Hence the following hypothesis is derived:

-

H6: The startup’s ambidexterity positively impacts its sustainability performance.

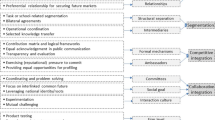

The research model we propose is reported in Fig. 1.

3 Methodology

This study utilized a structured survey approach to evaluate the impact of large corporations on the sustainability performance of startups engaged in asymmetric collaborations. The methodology was designed in distinct phases, each contributing critically to the comprehensive understanding of the research question. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the methodological approach adopted.

3.1 Survey design

We developed a structured questionnaire, consisting of 30 questions to capture the nuances of startups' sustainability performance under corporate influence. Each question is paired with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree". In addition, a specific section of the questionnaire was dedicated to gathering general and demographic information from startups participating in the study.

The original scales were in English; thus, we created the Italian version by adopting the standard translation and back-translation procedures and tested the survey readability and clarity (Podsakoff et al. 2003) through a pilot test to ten startups before the formal collection of data through large-scale quantitative research. This step allowed us to correct the potential issues identified by them (e.g. in terms of grammar errors or comprehension). All the measures employed were adapted from previously validated scales from extant research. Appendix 1 reports the details of each scale and the items included in the survey.

3.2 Sample identification and data collection

We surveyed born-sustainable Italian startups. We decided to focus on the Italian context; it represents a case of considerable interest in the startup landscape since it involved specific regulations and government support (Decree Law 179/12), and a specific classification of this type of company (Troise et al. 2022; Corvello et al. 2024b). For our survey, we identified potential startup participants through the special register for innovative startups, accessible at https://start-up.registroimprese.it/. Data were collected through a self-report survey (Ren et al. 2015). The questionnaire was disseminated in the period between December 2023 and January 2024 through Google Forms. Answers have been anonymized and items were intermixed, to reduce social desirability bias, retrieval bias and common method bias (Fisher 1993; Podsakoff et al. 2003). In total, 232 questionnaires were collected. At the beginning of the questionnaire, respondents were asked if sustainability represented a fundamental aspect of startup mission. Therefore, we discarded responses from startups not founded with declared sustainability objectives. As a result, for this study, we considered the responses from 189 born-sustainable startups. Table 1 presents a description of the sample, highlighting the characteristics of the startups participating in the study.

3.3 Data analysis

We employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) as a statistical method to empirically test the proposed research hypotheses (Dijkstra 2014). PLS-SEM was selected due to its suitability for small sample sizes (Willaby et al. 2015), its applicability in exploratory studies (Hair et al. 2019) and high recommendation for datasets with a limited number of indicators per latent variable (Hair et al. 2017). For the analysis, SmartPLS4 software from SmartPLS GmbH was utilized (additional information about SmartPLS4 can be accessed at https://www.smartpls.com). The analysis started with the evaluation of the measurement model to assess the reliability of the constructs utilized in the study. Following this, the evaluation of the structural model was carried out, to conclude the hypothesized relationships between the research model constructs and their statistical significance.

4 Results

4.1 Measurement model results

We started the evaluation of the measurement model with the assessment of the indicators' reliability (Hair et al. 2021). As shown in Table 2, none of the items had an outer loading lower than 0.6 (Chin 1998; Henseler et al. 2015).

We also assessed the Cronbach's alpha (Hair et al. 2017), Dillon-Goldstein's rho (Chin 1998) and the composite reliability (Hair et al. 2017). All constructs under examination fall within acceptable ranges, indicating that the internal consistency and reliability criteria are met (Hair et al. 2021). Moreover, we used the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) to assess convergent validity, All constructs exhibit AVE values surpassing the threshold limit of 0.5 (Hair et al. 2021), confirming the model's validity. The results of the construct reliability and validity analysis are reported in Table 3.

Discriminant validity results are reported in Table 4. Results show that each construct is truly distinct from other constructs in the model, by demonstrating that it shares more variance with its indicators than with other constructs in the model.

Discriminant validity was further tested, using the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Table 5). The results show that the square root of the AVE of each construct is greater than its highest correlation with any other construct, verifying the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Hair et al. 2017).

Finally, we performed the HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio) analysis. As reported in Table 6, the constructs are all below the threshold value; therefore, the discriminant validity between pairs of reflexive constructs has been confirmed.

4.2 Structural model results

We performed the structural model assessment by examining the presence of potential collinearity issues. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was used for this purpose (Hair et al. 2011). Table 7 reports the VIF values for each construct. None of them exceed the threshold limit of 5 (Hair et al. 2011), confirming the absence of collinearity issues in the structural model.

A bootstrap analysis with 5000 subsamples was performed (Hair et al. 2017) and the related path coefficients (reporting the significance levels), as well as hypothesis testing, are reported in Table 8. These values are displayed in Fig. 2. Finally, the R2 values have been evaluated and reported in Fig. 2, confirming the model’s predicting power. The PLS-SEM algorithm confirmed the formulated hypotheses.

The path coefficient between BCSO and SSG (β = 0.478, p < 0.001) indicates a substantial and significative impact of BCSO on SSG. The path value between BCPP and PT (β = 0.558, p < 0.001) also illustrates a positive and significant impact. BCPP has also a positive impact on SA (β = 0.379, p < 0.001). Concerning SSP, the PLS-SEM algorithm affirms the influence of all the hypothesized antecedents (SSG, PT, and SA) on the actual outcomes and impacts of a startup's sustainability efforts. The SSG construct exhibits the most substantial impact on SA (β = 0.566, p < 0.001). Results confirm also that PT has a significant and negative impact on SSP (β = -0.286, p < 0.001). Finally, we found that SA has a moderate impact on SSP (β = 0.129, p < 0.05).

Concluding the evaluation of the structural model, the assessment of the model's explanatory power was carried out through the coefficient of determination R2 (Shmueli and Koppius 2011). Figure 3 reports values showing the explanatory power of the proposed model (Hair et al. 2011).

5 Discussion and conclusion

The article aims to understand better how asymmetric collaboration with large corporations impacts the sustainability performance of startups. The research extends the existing literature by elucidating the mechanisms through which paradoxical tensions, arising from such collaborations, influence startup sustainability performance. We studied the role of startups' ambidexterity in managing these tensions and achieving sustainability goals.

As hypothesized, collaboration with large corporations has a profound impact on the sustainable performance of startups. It is widely recognized that these partnerships offer startups the capital and expertise needed to innovate and implement sustainable practices effectively (Bocken et al. 2015). Of note, exposure to the corporate partners' sustainability agendas and practices can instil a stronger orientation towards sustainability in startups (Schaltegger and Wagner 2011). However, while offering valuable resources and opportunities for growth, these partnerships also present challenges in balancing short-term operational demands with long-term sustainability goals (Pan et al. 2023).

Startups can navigate these challenges through strategies that promote ambidexterity, strategic alignment, leveraging of corporate resources for sustainability, maintaining sustainability as a core value, and effective negotiation and boundary setting. Building on the theoretical framework of paradoxical tensions (Smith and Lewis 2011), our findings attempt to shed light on the role of startup ambidexterity in navigating the complex dynamics of collaborations. This aligns with recent studies highlighting the importance of ambidexterity for startups (Chang et al. 2022) and, in particular, those engaging with large corporations (Muller et al. 2019; Khursheed and Mustafa 2024). Our research extends these insights by specifically linking ambidexterity to sustainability performance.

Paradoxical tensions are inherent in asymmetric collaborations between startups and large companies; they can dilute a startup's sustainability efforts if not appropriately managed. Startups may divert resources from long-term sustainability projects to meet the immediate operational demands of the corporate partner, potentially compromising their sustainability goals (Smith and Lewis 2011). The pressure to conform to the corporate partner's expectations and processes may stifle startups, limiting their ability to explore new sustainability opportunities. The cumulative effect of these tensions can lead to a strategic drift in startups, where their original mission and sustainability objectives become sidelined in favour of short-term gains (Karani and Mshenga 2021).

Ambidexterity may offer a pathway through which startups can navigate these tensions, by enabling them to simultaneously address immediate demands and pursue long-term sustainability goals. Ambidextrous organizations are more adaptable to changing environments. They can navigate the cultural and strategic differences between themselves and their corporate partners, reducing the likelihood of misalignments and conflicts (Weiss et al. 2023). By maintaining a focus on both exploratory and exploitative activities, startups can sustain their innovative capabilities, ensuring that their sustainability initiatives continue to evolve and improve over time (Yu and Zhu 2022). Effective negotiation strategies and setting clear boundaries with corporate partners are crucial. Startups need to negotiate terms that allow them to maintain their sustainability objectives while meeting the operational demands of the collaboration (Smith and Lewis 2011).

5.1 Theoretical implications

Our findings are in line with previous literature supporting that startups have to balance stakeholder’s requests in terms of operational efficiency (Bouncken and Kraus 2022) and sustainability (Ye et al. 2022). This adaptation ability reflects startups effort to align their behaviour with external expectations (Davidsson et al. 2006). In this way, sustainability and operational efficiency objectives can be compatible. Previous research (e.g. Horne and Fichter 2022) confirms this, demonstrating how growth and operational efficiency objectives are strategies that startups pursue to respond to the increasingly pressing need to obtain sustainability objectives. In the first instance, operational efficiency involves less waste of resources and therefore greater environmental and social sustainability (Parrish 2010). Moreover, treating sustainability as a goal represents a way for early movers to develop skills that guarantee a significant competitive advantage (Nidumolu et al. 2009).

5.2 Practical implications

The exploration of paradoxical tensions and ambidexterity in the realm of asymmetric collaborations between large companies and startups should lay the groundwork for actionable insights. Balancing operational efficiency with the ambition for long-term sustainability requires a nuanced approach, where startups can navigate the pressures exerted by their larger partners without losing sight of their sustainability ethos. Maintaining sustainability as a core value ensures that startups permeate tall strategic decisions and operations, thereby safeguarding their innovative edge and commitment to sustainability despite external pressures. Results suggest that, if appropriately addressed, sustainability goals do not necessarily conflict with the pressure for operational efficiency and economic growth. Startups should implement strategies that address both dimensions simultaneously. This approach may enhance a start-up's ability to adapt to stakeholder expectations and foster positive performance outcomes.

Overall, our findings suggest a practical roadmap for startups striving to maintain their sustainability commitments while leveraging the resources of large corporate partners. This is particularly relevant in light of research indicating that startups often struggle to balance the immediate benefits of collaboration with their long-term sustainability goals (Bocken et al. 2020). For corporations, our study underscores the strategic importance of fostering a sustainability-oriented culture that supports their startup partners' sustainability initiatives, aligning with insights from Schaltegger and Wagner (2011) on corporate sustainability. The implications of our findings extend beyond the immediate stakeholders to policymakers and innovation ecosystem architects. By demonstrating the value of ambidexterity in sustaining innovative and sustainable growth, the research supports the call for policies that nurture these capabilities in startups. This aligns with the European Commission efforts to enhance innovation through startup-corporate collaboration (European Commission 2018), emphasizing the need for sustainability-oriented policy frameworks.

5.3 Final remarks

This research investigated the collaboration dynamics between startups and large corporations, focusing on factors influencing the sustainability performance of startups. Through a comprehensive survey of 189 Born-Sustainable Italian startups engaged in open innovation initiatives with large corporations, this study highlighted the critical role of paradoxical tensions and the startups' ambidexterity in navigating the pressures exerted by large corporations. Our findings provide compelling evidence that, despite the challenges, startups can leverage collaborations to enhance their sustainability performance, provided they skillfully manage the paradoxical tensions and maintain their ambidextrous capabilities.

This research reveals that the sustainability orientation of large companies influences the definition of startup performance goals and, consequently, the sustainability performance of startups. However, when large companies exert excessive pressure on startups, they generate paradoxical tensions with a negative impact on performance. Startup ambidexterity is one approach to mitigate these negative effects. Successfully navigating these collaborations requires startups to balance the competing demands of cooperation and competition, leveraging both to foster innovation and sustainability. The study underscores the importance of startups maintaining their agility and innovative capacity, even as they engage with larger, resource-rich partners. For large corporations, there is a clear indication of the benefits of supporting startups' sustainability efforts, suggesting a mutual growth opportunity that aligns with broader societal and environmental goals. Policymakers are encouraged to foster an environment that supports such symbiotic relationships, emphasizing the critical role of ambidextrous capabilities in driving sustainable innovation within the startup ecosystem.

5.4 Limitations and further studies

This study exhibits some limitations, Firstly, the study is restricted to a specific geographic area, namely Italy, and the findings may be influenced by this specific context. Different cultural, economic, and regulatory environments could impact the dynamics of startup-corporate collaborations and their sustainability outcomes. Future research avenues could address these limitations by exploring startup-corporate collaborations in various geographical locations and industries to understand the influence of cultural and sectoral differences. Self-reported survey data may introduce potential biases, as respondents may overestimate their sustainability performance. Further studies using specific and measurable performance indicators for startups could provide more useful insights. Finally, the cross-sectional design of the survey limits the ability to observe the evolution of these collaborations and their impact over time. Longitudinal studies could provide insights into the long-term outcomes of these collaborations, while qualitative case studies could offer a deeper understanding of how startups navigate paradoxical tensions and manage ambidexterity. Investigating the role of digital technologies in these dynamics could also unveil new strategies and challenges, enriching our understanding of sustainable innovation in the startup ecosystem.

References

Aaboen L, Aarikka-Stenroos L (2017) Start-ups initiating business relationships: process and asymmetry. IMP Journal 11(2):230–250

Akinremi T, Roper S (2021) The collaboration paradox: why small firms fail to collaborate for innovation. Managing Collaborative R&D Projects: Leveraging Open Innovation Knowledge-Flows for Co-Creation 139–159

Allmendinger MP, Berger ES (2020) Selecting corporate firms for collaborative innovation: entrepreneurial decision making in asymmetric partnerships. Int J Innov Manag 24(01):2050003

Amankwah‐Amoah, J, Danso A, Adomako S (2019) Entrepreneurial orientation, environmental sustainability and new venture performance: does stakeholder integration matter? Bus Strateg Environ 28(1):79–87

Andriopoulos C, Lewis MW (2009) Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organ Sci 20(4):696–717

Audretsch DB, Belitski M, Eichler GM, Schwarz E (2024) Entrepreneurial ecosystems, institutional quality, and the unexpected role of the sustainability orientation of entrepreneurs. Small Bus Econ 62(2):503–522

Balboni B, Bortoluzzi G, Pugliese R, Tracogna A (2019) Business model evolution, contextual ambidexterity and the growth performance of high-tech start-ups. J Bus Res 99:115–124

Bereczki I (2019) An open innovation ecosystem from a startup’s perspective. Int J Innov Manag 23(08):1940001

Blome C, Paulraj A, Preuss L, Roehrich JK (2023) Trust and opportunism as paradoxical tension: Implications for achieving sustainability in buyer-supplier relationships. Ind Mark Manage 108:94–107

Bocken NM (2015) Sustainable venture capital–catalyst for sustainable start-up success? J Clean Prod 108:647–658

Bocken N (2020) Sustainable business models. In: Decent Work and Economic Growth. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 963–975

Bouncken RB, Kraus S (2022) Entrepreneurial ecosystems in an interconnected world: emergence, governance and digitalization. RMS 16(1):1–14

Bronnenmayer M, Wirtz BW, Göttel V (2016) Success factors of management consulting. RMS 10:1–34

Cacciolatti L, Rosli A, Ruiz-Alba JL, Chang J (2020) Strategic alliances and firm performance in startups with a social mission. J Bus Res 106:106–117

Castellani P, Rossato C, Giaretta E, Vargas-Sánchez A (2024) Partner selection strategies of SMEs for reaching the sustainable development goals. Rev Manag Sci 18(5):1317–1352

Chang YY, Hughes M (2012) Drivers of innovation ambidexterity in small-to medium-sized firms. Eur Manag J 30(1):1–17

Chang CY, Chang YY, Tsao YC, Kraus S (2022) The power of knowledge management: how top management team bricolage boosts ambidexterity and performance. J Knowl Manag 26(11):188–213

Chappert C, Fernandez AS, Pierre A (2024) Corporation–start-up collaboration: how can the tensions stemming from asymmetries be managed? Ind Innov 31(5):666–693

Chesbrough H (2017) The future of open innovation: The future of open innovation is more extensive, more collaborative, and more engaged with a wider variety of participants. Res Technol Manag 60(1):35–38

Chin WW (1998) Commentary: issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q 22(1):7–16

Ching HY, Caetano RM (2021) Dynamics of corporate startup collaboration: an exploratory study. J Manag Res 13(2):22

Chou HH, Zolkiewski J (2018) Coopetition and value creation and appropriation: The role of interdependencies, tensions and harmony. Ind Mark Manage 70:25–33

Ciasullo MV, Montera R, Cucari N, Polese F (2020) How an international ambidexterity strategy can address the paradox perspective on corporate sustainability: Evidence from Chinese emerging market multinationals. Wiley Online Library 29(5):2110–2129. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2490

Corallo A, De Giovanni M, Latino ME, Menegoli M (2023) Leveraging on technology and sustainability to innovate the supply chain: a proposal of agri-food value chain model. Supply Chain Manag Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-12-2022-0484

Corvello V, Felicetti AM, Steiber A, Alänge S (2023) Start-up collaboration units as knowledge brokers in Corporate Innovation Ecosystems: a study in the automotive industry. J Innov Knowl 8(1):100303

Corvello V, Felicetti AM, Ammirato S, Troise C, Ključnikov A (2024a) The rules of courtship: What drives a start-up to collaborate with a large company? Technol Forecast Soc Chang 200:123092

Corvello V, Felicetti AM, Troise C, Tani M (2024b) Betting on the future: how to build antifragility in innovative start-up companies. Rev Manag Sci 18(4):1101–1127

Crapa G, Latino ME, Roma P (2024) The performance of green communication across social media: Evidence from large-scale retail industry in Italy. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 31(1):493–513

Davidsson P, Hunter E, Klofsten M (2006) Institutional forces: The invisible hand that shapes venture ideas? Int Small Bus J 24(2):115–131

De Groote JK, Backmann J (2020) Initiating open innovation collaborations between incumbents and startups: How can David and Goliath get along? Int J Innov Manag 24(02):2050011

Deyanova K, Brehmer N, Lapidus A, Tiberius V, Walsh S (2022) Hatching start-ups for sustainable growth: a bibliometric review on business incubators. RMS 16(7):2083–2109

Di Vaio A, Hassan R, Chhabra M, Arrigo E, Palladino R (2022) Sustainable entrepreneurship impact and entrepreneurial venture life cycle: A systematic literature review. J Clean Prod 378:134469

Dijkstra TK (2014) PLS’ Janus Face – Response to Professor Rigdon’s ‘Rethinking Partial Least Squares Modeling. In Praise of Simple Methods. Long Range Plann 47(3):146–153

Dizdarevic A, van de Vrande V, Jansen J (2023) When opposites attract: a review and synthesis of corporate-startup collaboration. Ind Innov 31(5):544–578

Elkington J (1998) Accounting for the Triple Bottom Line. Meas Bus Excell 2(3):18–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/EB025539/FULL/HTML

Emden Z, Calantone RJ, Droge C (2006) Collaborating for new product development: selecting the partner with maximum potential to create value. J Prod Innov Manag 23(4):330–341

European Commission (2018) Startup Europe: connecting ecosystems for European innovation. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/startup-europe. Accessed 27 Apr 2024

Feng Y, Teng D, Hao B (2019) Joint actions with large partners and small-firm ambidexterity in asymmetric alliances: The mediating role of relational identification. Int Small Bus J 37(7):689–712

Fernandes AJ, Ferreira JJ (2022) Entrepreneurial ecosystems and networks: a literature review and research agenda. RMS 16(1):189–247

Fisher RJ (1993) Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J Consum Res 20(2):303–315

Fortes MVB, Agostini L, Wegner D, Nosella A (2023) Paradoxes and tensions in interorganizational relationships: A systematic literature review. J Risk Financ Manage 16(1):35

Galati F, Bigliardi B, Galati R, Petroni G (2021) Managing structural inter-organizational tensions in complex product systems projects: Lessons from the Metis case. J Bus Res 129:723–735

Galkina T, Atkova I, Yang M (2022) From tensions to synergy: causation and effectuation in the process of venture creation. Strateg Entrep J 16(3):573–601

Gelhard C, Von Delft S (2016) The role of organizational capabilities in achieving superior sustainability performance. J Bus Res 69(10):4632–4642

Gernsheimer O, Kanbach DK, Gast J, Le Roy F (2024) Managing paradoxical tensions to initiate coopetition between MNEs: The rise of coopetition formation teams. Ind Mark Manage 118:148–174

Giglio C, Corvello V, Coniglio IM, Kraus S, Gast J (2023) Cooperation between large companies and start-ups: an overview of the current state of research. European Manage J

Gimenez-Fernandez EM, Sandulli FD, Bogers M (2020) Unpacking liabilities of newness and smallness in innovative start-ups: Investigating the differences in innovation performance between new and older small firms. Res Policy 49(10):104049

Glasbergen P, Biermann F, Mol AP (eds) (2007) Partnerships, governance and sustainable development: Reflections on theory and practice. Edward Elgar Publishing

Gutmann T, Lang C (2022) Unlocking the magic of corporate-startup collaboration: How to make it work. IEEE Eng Manage Rev 50(2):19–25

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract 19:139–151

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Gudergan SP (2017) Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage publications

Hair F, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hair JF Jr., Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S (2021) Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. Springer publications. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

Halberstadt J, Niemand T, Kraus S, Rexhepi G, Jones P, Kailer N (2021) Social entrepreneurship orientation: Drivers of success for start-ups and established industrial firms. Ind Mark Manage 94:137–149

Hao B, Feng Y (2018) Leveraging learning forces in asymmetric alliances: small firms’ perceived power imbalance in driving exploration and exploitation. Technovation 78:27–39

Harangozo G, Csutora M, Kocsis T (2018) How big is big enough? Toward a sustainable future by examining alternatives to the conventional economic growth paradigm. Sustain Dev 26(2):172–181

Hart SL (1995) A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad Manag Rev 20(4):986–1014

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135

Hoogendoorn B, van der Zwan P, Thurik R (2019) Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Perceived Barriers and Risk. J Bus Ethics 157(4):1133–1154. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10551-017-3646-8

Hora W, Gast J, Kailer N, Rey-Marti A, Mas-Tur A (2018) David and Goliath: causes and effects of coopetition between start-ups and corporates. RMS 12:411–439

Horne J, Fichter K (2022) Growing for sustainability: Enablers for the growth of impact startups – A conceptual framework, taxonomy, and systematic literature review. J Clean Prod 349:131163

Ilin V, Ivetić J, Simić D (2017) Understanding the determinants of e-business adoption in ERP-enabled firms and non-ERP-enabled firms: A case study of the Western Balkan Peninsula. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 125:206–223

Jackson N, Steiber A (2019) New economies’ governance in the age of digital transformation: the sociological orientation’s effect on a nation’s digital transformation. Working Paper, AOM Responsible Leadership Conference October

Jagani S, Hong P (2022) Sustainability orientation, byproduct management and business performance: An empirical investigation. J Clean Prod 357:131707

Junni P, Sarala RM, Taras V, Tarba SY (2013) Organizational ambidexterity and performance: A meta-analysis. Acad Manag Perspect 27(4):299–312. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2012.0015

Kaczam F, Siluk JCM, Guimaraes GE, de Moura GL, da Silva WV, da Veiga CP (2022) Establishment of a typology for startups 4.0. Rev Manage Sci 16(3):649–680

Karani C, Mshenga P (2021) Steering the sustainability of entrepreneurial start-ups. J Glob Entrep Res 11(1):223–239

Khursheed A, Mustafa F (2024) Role of innovation ambidexterity in technology startup performance: an empirical study. Technol Anal Strateg Manage 36(1):29–44

Klein M, Neitzert F, Hartmann-Wendels T, Kraus S (2019) Start-up financing in the digital age: A systematic review and comparison of new forms of financing. J Entrep Finance (JEF) 21(2):46–98

Kraus S, Filser M, O’Dwyer M, Shaw E (2020a) Social entrepreneurship: An exploratory citation analysis. RMS 14:209–233

Kraus S, Clauss T, Breier M, Gast J, Zardini A, Tiberius V (2020b) The economics of COVID-19: initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. Int J Entrep Behav Res 26(5):1067–1092

Lisi IE (2018) Determinants and Performance Effects of Social Performance Measurement Systems. J Bus Ethics 152(1):225–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10551-016-3287-3

March JG (1991) Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ Sci 2(1):71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/ORSC.2.1.71

Margherita A, Elia G, Baets WR, Andersen TJ (2020) Corporate “Excelerators”: How Organizations Can Speed Up Crowdventuring for Exponential Innovation. In: Innovative Entrepreneurship in Action (pp 71–91). Springer, Cham

Müller SD, Påske N, Rodil L (2019) Managing ambidexterity in startups pursuing digital innovation. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 44(1):18

Muñoz P, Dimov D (2015) The call of the whole in understanding the development of sustainable ventures. J Bus Ventur 30(4):632–654

Nidumolu R, Prahalad CK, Rangaswami MR (2009) Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harv Bus Rev 87(9):56–64

Nyaga GN, Lynch DF, Marshall D, Ambrose E (2013) Power asymmetry, adaptation and collaboration in dyadic relationships involving a powerful partner. J Supply Chain Manag 49(3):42–65

Nylund PA, Brem A, Agarwal N (2021) Innovation ecosystems for meeting sustainable development goals: the evolving roles of multinational enterprises. J Clean Prod 281:125329

O’Reilly CA III, Tushman ML (2013) Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Acad Manag Perspect 27(4):324–338

Pan L, Xu Z, Skare M (2023) Sustainable business model innovation literature: a bibliometrics analysis. RMS 17(3):757–785

Papachroni A, Heracleous L, Paroutis S (2016) In pursuit of ambidexterity: Managerial reactions to innovation–efficiency tensions. Human Relations 69(9):1791–1822. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715625343

Parrish BD (2010) Sustainability-Driven Entrepreneurship: Principles of Organization Design. J Bus Ventur 25(5):510–523

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879

Prashantham S, Kumar K (2019) Engaging with startups: MNC perspectives. IIMB Manag Rev 31(4):407–417

Primario S, Rippa P, Secundo G (2024) Peer innovation as an open innovation strategy for balancing competition and collaboration among technology start-ups in an innovation ecosystem. J Innov Knowl 9(2):100473

Raza-Ullah T (2020) Experiencing the paradox of coopetition: A moderated mediation framework explaining the paradoxical tension–performance relationship. Long Range Plan 53(1):101863

Remneland Wikhamn B (2020) Open innovation change agents in large firms: How open innovation is enacted in paradoxical settings. R&D Manage 50(2):198–211

Ren S, Eisingerich AB, Tsai H-T (2015) How do marketing, research and development capabilities, and degree of internationalization synergistically affect the innovation performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)? A panel data study of Chinese SMEs. Int Bus Rev 24(4):642–651

Rey-Garcia M, Mato-Santiso V, Felgueiras A (2021) Transitioning collaborative cross-sector business models for sustainability innovation: multilevel tension management as a dynamic capability. Bus Soc 60(5):1132–1173

Rigtering JC, Behrens MA (2021) The effect of corporate—start-up collaborations on corporate entrepreneurship. RMS 15(8):2427–2454

Rojas-Córdova C, Williamson AJ, Pertuze JA, Calvo G (2023) Why one strategy does not fit all: a systematic review on exploration–exploitation in different organizational archetypes. RMS 17(7):2251–2295

Runge S, Schwens C, Schulz M (2022) The invention performance implications of coopetition: How technological, geographical, and product market overlaps shape learning and competitive tension in R&D alliances. Strateg Manag J 43(2):266–294

Sánchez-Robles M, Saura JR, Ribeiro-Soriano D (2023) Overcoming the challenges of cooperative startups businesses: insights from a bibliometric network analysis. RMS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-023-00670-9

Schaltegger S, Wagner M (2011) Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: categories and interactions. Bus Strateg Environ 20(4):222–237

Schindler J, Kallmuenzer A, Valeri M (2024) Entrepreneurial culture and disruptive innovation in established firms – how to handle ambidexterity. Bus Process Manag J 30(2):366–387

Sharma A, Kearins K (2011) Interorganizational Collaboration for Regional Sustainability. J Appl Behav Sci 47(2):168–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886310381782

Shmueli G, Koppius OR (2011) Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS Q 35(3):553–572

Smith W, Lewis M (2011) Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Acad Manag Rev 36(2):381–403. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2009.0223

Spender JC, Corvello V, Grimaldi M, Rippa P (2017) Startups and open innovation: a review of the literature. Eur J Innov Manag 20(1):4–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-12-2015-0131/FULL/

Steiber A, Alänge S (2021) Corporate-startup collaboration: effects on large firms’ business transformation. Eur J Innov Manag 24(2):235–257

Steiber A, Alänge S, Corvello V (2020) Learning with startups: an empirically grounded typology. Learn Organ 28(2):153–166

Ten Buuren N (2017) Understanding the effects of power asymmetry on a start ups’ innovation performance. Retrieved from https://essay.utwente.nl/73812/. Accessed 27 Jan 2024

Todeschini BV, Cortimiglia MN, Callegaro-de-Menezes D, Ghezzi A (2017) Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Bus Horiz 60(6):759–770

Troise C, Dana LP, Tani M, Lee KY (2022) Social media and entrepreneurship: exploring the impact of social media use of start-ups on their entrepreneurial orientation and opportunities. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 29(1):47–73

Usman M, Vanhaverbeke W (2017) How start-ups successfully organize and manage open innovation with large companies. Eur J Innov Manag 20(1):171–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-07-2016-0066/FULL/HTML

Utomo P, Kurniasari F (2023) The dynamic capability and ambidexterity in the early-stage startups: a hierarchical component model approach. Eurasian Stud Bus Econ 25:49–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36286-6_3

Venkobarao V (2019) Avoid Startup Traps. IEEE Eng Manage Rev 47(3):39–41

Voinea CL, Logger M, Rauf F, Roijakkers N (2019) Drivers for sustainable business models in start-ups: Multiple case studies. Sustainability 11(24):6884

Volkmann C, Fichter K, Klofsten M, Audretsch DB (2021) Sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: an emerging field of research. Small Bus Econ 56(3):1047–1055. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11187-019-00253-7

Walker AM, Vermeulen WJV, Simboli A, Raggi A (2021) Sustainability assessment in circular inter-firm networks: An integrated framework of industrial ecology and circular supply chain management approaches. J Clean Prod 286. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2020.125457

Wang YM, Wang YS, Yang YF (2010) Understanding the determinants of RFID adoption in the manufacturing industry. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 77(5):803–815

Weiblen T, Chesbrough HW (2015) Engaging with startups to enhance corporate innovation. Calif Manage Rev 57(2):66–90

Weiss L, Kanbach DK, Kraus S, Dabić M (2023) Strategic corporate venturing in interlinked ambidextrous units: an exploratory model. European Manag J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2023.02.003

Wilkinson I, Young L (2002) On cooperating: firms, relations and networks. J Bus Res 55(2):123–132

Willaby HW, Costa DSJ, Burns BD, MacCann C, Roberts RD (2015) Testing complex models with small sample sizes: a historical overview and empirical demonstration of what partial least squares (PLS) can offer differential psychology. Personal Individ Differ 84:73–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.008

Williamson OE (1991) Comparative economic organization: the analysis of discrete structural alternatives, administrative science quaterly, vol 36. The Mechanisms of Governance 93–119

Ye F, Yang Y, Xia H, Shao Y, Gu X, Shen J (2022) Green entrepreneurial orientation, boundary-spanning search and enterprise sustainable performance: the moderating role of environmental dynamism. Front Psychol 13:978274

Yu J, Zhu L (2022) Corporate ambidexterity: Uncovering the antecedents of enduring sustainable performance. J Clean Prod 365:132740

Acknowledgements

This research has been partially funded within the framework of the PRIN – PNRR 2022 Project INSPIRE: Digital INnovation EcoSystem DeveloPment for the CIRcular Economy: the startups' perspective- P20224A38A, CUP H53D23008240001, funded by EU in NextGenerationEU plan through the Italian " Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca - Bando Prin 2022 - D.D. 1409 del 14-09-2022").

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università della Calabria within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1. Measures

Appendix 1. Measures

CONSTRUCT | VARIABLE | ITEM | SOURCE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

BCSO | Big Corp Sustainable Orientation | BCSO1 | Our partner feels that social responsibility is a critically important issue facing the world today | (Lisi 2018) |

BCSO2 | Our partner is very concerned about social problems, e.g., work-related injuries, human rights violations, corruption | |||

BCSO3 | Our partner is increasingly providing healthier and safer products and services | |||

BCSO4 | Our partner expect our firm to be socially responsible | |||

SA | Startup Ambidexterity | –- exploitation –- | Chang & Hughes, (2012) | |

SA1 | We improve our provisions efficiency of products and services | |||

SA2 | We increase economies of scales in existing markets | |||

SA3 | Our company expands services for existing clients | |||

–- exploration –- | ||||

SA4 | We aim to quickly adapt our company to changing external conditions and market dynamics | |||

SA5 | We aim to provide new-to-market products or services | |||

SA6 | We aim to introduce new generations of products leveraging on ongoing technological advancements | |||

SSG | Startup Sustainability Goals | SSG1 | Improving health and well-being | Muñoz and Dimov (2015) |

SSG2 | Creating and distributing economic value amongst all stakeholders | |||

SSG3 | Improving the quality of life in a particular community | |||

SSG4 | Creating employment opportunities | |||

SSG5 | Protecting or restoring the natural environment | |||

SSG6 | Creating ethical and fair products | |||

SSG7 | Establishing fair trading with suppliers | |||

SSG8 | Promoting democratic business models | |||

SSP | Startup Sustainability Performance | SSP1 | We are the first that offer environmental-friendly products/services at the marketplace | (Gelhard and Delft 2016) |

SSP2 | Our competitors consider us as a leading company in the field of sustainability | |||

SSP3 | We develop new products/services or improve existing products/services that are regarded as sustainable for society and environment | |||

SSP4 | Our reputation in terms of sustainability is better than the sustainability reputation of our competitors | |||

SSP5 | Compared to our competitors, we more thoroughly respond to societal and ethical demands | |||

BCPP | Big Corp Perceived Pressure | BCPP1 | The large company partner recommended us to reduce operational costs | |

BCPP2 | The large company partner requested us to increase our operational efficiency | |||

BCPP3 | The large company partner encouraged us to streamline our processes | |||

PT | Paradoxical Tension | In the relationship with a big corporation, you perceive that it is difficult to… | Raza-Ullah (2020) | |

PT1 | Both cooperate in some areas and compete in others | |||

PT2 | Both build a close relationship and keep some distance | |||

PT3 | Both share knowledge and protect important knowledge | |||

PT4 | Both learn from each other and win the learning race |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ammirato, S., Felicetti, A.M., Filippelli, S. et al. Navigating paradoxical tension: the influence of big corporations on startup sustainability performance in asymmetric collaborations. Rev Manag Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-024-00777-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-024-00777-7