Abstract

This study analyses the impact of the critical issues on Travel and Tourism e-service failure and explores specifically how peer-to-peer accommodation business can cope with the potential collapse in demand caused by global crises. The purpose is to examine the impact of peer-to-peer accommodation’s recovery offer on revisiting intentions and relationships termination in light of justice-, fairness-, and attribution theory. In this vein, the main aim is to develop a theoretical model which is underpinned by an understanding of the consequences of e-service failure and the effectiveness of recovery strategies for business competitiveness. To gauge peer perceptions of peer-to-peer accommodations, we employed a mixed-method approach. Alongside 17 interviews with peers and industry experts, a survey involving 404 peer-to-peer accommodation users was conducted. Structural equation modelling was applied to unravel the intricate relationships and influences at play. The findings suggest that managers and service providers need to focus on timely recovery and building stronger relationships with peers, to increase repurchase intention and post-recovery satisfaction and to better front the crises times. This could be implemented efficiently via the platform of social media. This study offers specific theoretical and practical implications by providing a fair recovery strategy to result in the satisfaction of both parties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The term "service failure" has gained popularity among researchers and practitioners in the past two decades (Azemi et al. 2019). Service failures occur when one or more aspects of service quality are not delivered properly, resulting in customer dissatisfaction (Foroudi et al. 2020a, b, c; Jung and Seock 2018). These failures lead to a breakdown in service expectations, which negatively impacts customer loyalty, word-of-mouth, and retention. Previous research has shown that the absence of negative critical incidents is a key factor in customers staying with a service provider despite issues with switching (Colgate et al. 2007). This highlights how service failure disrupts service expectations and leads to customer disconfirmation.

There is a vast body of research on service failure, behavioral attitudes, justice perception, customer issue resolution, and switch intention (Chen et al. 2018; Albrecht et al. 2017; Lee and Cranage 2017). When service failures occur, customers engage in complaint procedures to address the problems (Balaji et al. 2015; Hong and Lee 2005; Tsarenko and Strizhakova 2013). They use various channels to voice their complaints, such as face-to-face contact, phone calls, emails, and increasingly, social media platforms (Balaji et al. 2015; Foroudi et al. 2020a, b, c; Tripp and Grégoire 2011; Ruiz-Alba et al. 2022). Social media has provided customers with an outlet to express their dissatisfaction and seek solutions online.

Effective service failure recovery (SFR) is crucial for organizations, as studies have shown that customers expect successful recovery efforts when failures occur (Bitner et al. 1990; Zeithaml et al. 1996). Recovery efforts positively impact customer satisfaction, which in turn increases loyalty. Therefore, managing online service failures presents significant challenges for businesses. There is a wide range of research in the areas of services failure (Loo and Leung 2018), behavioural attitudes (Albrecht et al. 2017; Lee and Cranage 2017), perception of justice, resolving customer related issues and switchover intention (Chen et al. 2018). When failures do happen, customers take part in complaints procedures to resolve the problems (Balaji et al. 2015; Hong and Lee 2005; Tsarenko and Strizhakova 2013). They may use various routes to pursue their complaints, for example, face-to-face contact, telephone calls or emails; the ongoing development of social media has also enabled many customers to protest online and vent their dissatisfaction (Balaji et al. 2015; Foroudi et al. 2020a, b, c; Tripp and Grégoire 2011; Ruiz-Alba et al. 2022).

As the pivotal studies about the effect of service failure recovery (SFR) on customers had highlighted (Bitner et al. 1990; Zeithaml et al. 1996) when some service failure occurred customers expect effective recoveries. Recovery indeed improves customer satisfaction which in turn increases loyalty.

Therefore, managing online service failures presents significant challenges for businesses. E-service failure has been explored in various research disciplines, including management, business and production (Alguacil et al. 2021; Choi and Mattila 2008), the service industry, marketing and customer behaviours (Azemi and Ozuem 2016), innovation failure (Rhaiem and Amara 2021; Shaik et al. 2023; Sreen et al. 2023). However, this has evidently not been analysed in times of crisis (as for example during the Covid-19 pandemic: Curran and Eckhardt 2021; Emami et al. 2022; Izadi et al. 2021).

Several factors distinguish e-services from traditional services in terms of service quality and service failure recovery (SFR) (Azemi and Ozuem 2016; Azemi et al. 2020). Online service failure occurs when an e-service organization fails to meet customer expectations (Migacz et al. 2018). The reduced level of human engagement and the reliance on technology to facilitate consumer interaction are key issues in the context of e-services (Holloway and Beatty 2003). Consequently, the factors that contribute to the quality of e-services differ from those associated with traditional services (Sousa and Voss 2006). These distinctions have significant implications for various industries, particularly travel and tourism (T&T) and global peer-to-peer (P2P) accommodation platforms (Courtney 2020; Hoisington 2020; Palos-Sanchez et al. 2021). P2P accommodation platforms have emerged as new marketplaces for exchanging accommodation services and have become the most profitable sector in the T&T industry (PwC 2016). The advent of P2P accommodation has revolutionized the tourist experience (Garau-Vadell et al. 2021). P2P accommodation refers to online networking platforms that enable individuals to rent out either vacant spaces within their property or their entire property for short durations (Farmaki and Miguel 2022). Potential customers access these e-services through digital platforms that allow them to evaluate options and make bookings. The World Economic Forum (2017) estimated that by 2025, the P2P accommodation market will generate $8 billion in annual profits, posing a significant challenge to the hotel industry. However, it is important to note that this growth forecast has been heavily influenced by the impact of recent global crises on business strategies (Foroudi et al. 2021).

The nature of P2P tourism e-services require proper recovery measures. However, the relationship between the effects of service failures and recovery (SFR) and peer attitudes, expectation and future intention has received only limited attention in the context of e-services.

In this scenario, this study aims to explore how peer-to-peer accommodation can bounce back from e-service failure and crisis times. The main goal is to answer the three research questions identified in the bibliometric study conducted by Foroudi et al. (2020a, b, c): (i) How does the e-service failure affect the peer’s attitude? (ii) How does the peer’s attitude affect the peer’s expectation in the recovery strategy and proposed resolution provided by the service provider? (iii) How could the service recovery strategies impact on a peer’s future repurchasing intention and relationship termination?

Based on attribution theory, fairness theory and justice theory, this research explores further consequences of the e-service failure and sustainable recovery strategies that seem challenging for businesses and customers due to the recent period of global crises.

Furthermore, several studies have highlighted the significant impact of social media on customer repurchase intention and its role in enhancing customers’ communication power (Israeli et al. 2019; Koronios et al. 2021). For instance, Israeli et al. (2019) found that social media platforms have a substantial influence on customers’ decision to repurchase products or services. Similarly, Koronios et al. (2021) emphasized the importance of social media in shaping customers’ repurchase intentions in the context of online retail.

In the hospitality and retail industries, social media plays a crucial role in building strong and long-term relationships with customers (Melewar et al. 2017). Melewar et al. (2017) conducted a study that demonstrated the significant impact of social media on customer engagement and loyalty in the hospitality and retail sectors. They found that businesses in these industries can effectively utilize social media platforms to engage with customers, promote their offerings, and establish a favorable brand image.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) particularly benefit from leveraging social media platforms for various purposes. SMEs use social media to boost sales, advertise their products or services, and engage with customers (Israeli et al. 2019; Magni et al. 2023). By effectively utilizing social media, SMEs can reach a wider audience, increase brand visibility, and attract potential customers. Additionally, social media platforms have become a popular avenue for customers to express their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with a company’s products or services. In the event of an online service failure, customers often turn to social media to share their purchase experiences, seek resolutions to their issues, and even seek retribution (Israeli et al. 2019). This highlights the importance of actively monitoring and responding to customer feedback on social media platforms to maintain a positive brand image and customer satisfaction.

Moreover, the global health crisis has further emphasized the crucial role of social media for both organizations and individuals. With the restrictions imposed on physical interactions, social media has become a primary channel for communication, information dissemination, and customer engagement. Companies have had to adapt their strategies to leverage social media effectively to reach and engage with their target audience during these challenging times.

In conclusion, social media plays a vital role in the competitive business landscape, influencing customers’ intention to repurchase and enhancing their communication power. It is particularly significant in the hospitality and retail sectors for building strong customer relationships. Small and medium-sized enterprises can benefit greatly from utilizing social media platforms to drive sales and engage with customers. Additionally, social media serves as a platform for customers to share their experiences, seek resolutions, and express their opinions. Given the global health crisis, the role of social media has become even more crucial for organizations and individuals alike, serving as a primary channel for communication and engagement. (Israeli et al. 2019; Koronios et al. 2021; Melewar et al. 2017).

Based on the results of qualitative and quantitative studies, this article discusses the fundamentals and consequences of e-service failure, which influence customers’ attitudes, intention to repurchase, potential relationship-ending and e-recovery offers during global health crises. This research helps businesses such as Airbnb with crisis management and resolution strategies to handle e-service failure (Spillan et al. 2021) and deal with e-complaints during world health crises. Furthermore, it supports practitioners in understanding the importance of recovery strategies after e-service failure and how they can increase their customers repurchase intention (Weber et al. 2016) considering the knowledge perspectives (Abbas and Khan 2023; Sreen et al. 2023). Social media, online service failure and recovery strategies are significant factors driving customers repurchase intention and switchover intention, especially after the unprecedented Covid-19 pandemic outbreak. In the past two decades, marketers and practitioners have made tremendous steps forward in the fields of the relationship between service failure and recovery (Azemi and Ozuem 2016). However, there is little academic research on service failure and recovery in the context of social media (Obeidat et al. 2017) and robotics (Callarisa-Fiol et al. 2023), particularly during the global health crises.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 E-service failure and recovery strategies in crisis times

The travel industry (Dalwai and Sewpersadh 2023) such as hotels exposed to pressures caused by unforeseen disasters such as natural tragedies and terrorist outbreaks (Chan and Lam 2013; Chen 2011; Foroudi and Marvi 2020; Jayawardena et al. 2008; Paraskevas 2013; Racherla and Hu 2009). As a consequence of any catastrophe in crisis epoch, the travel and tourism industry need to put strict measures in place to handle their visitors’ and travellers’ safety (Chan and Lam 2013), as do other businesses such as Airbnb. For example, under the new global health crises caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, more harsh safety measures such as strict hygiene protocol and travel restrictions have been enforced (OECD 2020). However, there is very limited research on how to minimise service failure and enhance the recovery strategies in the case of a crisis period (Xu et al. 2022). Furthermore, in the context of the travel and hospitality industry, effective knowledge management (Umar et al. 2021; Anand et al. 2022; Duan et al. 2023; Felicetti et al. 2023; Issah et al. 2023; Serenko 2024; Truong et al. 2023) and change management (Korherr and Kanbach 2023) are crucial components for successfully navigating and recovering from crises such as natural disasters, terrorist outbreaks, and pandemics, improving decision making processes to front new dangerous situations.

Service failures particularly refer to situations in which customers are dissatisfied because their perception of a service they have received is worse than their expectation (Migacz et al. 2018). Choi and Mattila (2008) suggest the reason for service failure can be connected to e-service providers, e-payment systems, switching costs, websites or other unknown factors (such as marketers or customers). The less successful the organisation is in resolving the failure, the lower the customer’s loyalty, repurchase intention and tendency to suggest positive word-of-mouth (WOM) (Azemi et al. 2019). In the context of the pandemic, when there is a highly contagious global disease (Chan et al. 2020), people are requested to follow some highly restricted protocol such as social distancing and lockdown requested by WHO (WHO 2020a). This accelerates changes and dependency on contactless and technology-based services in every business (Klein et al. 2021), especially hotels and peer-to-peer accommodation. Moreover, this increases the service bias and failure at the beginning of the outbreak when there was a large number of cancellations and refunds.

Hence, service recovery refers to the actions and activities that the service organisation and its employees perform to rectify, amend and restore the loss experienced by customers as a result of the failures of in-service performance (Chen et al. 2018; Hess et al. 2003). Kim and Ulgado (2012) suggest that service recovery, dependent on the apparent value of the effort made, can powerfully affect the connections between customers and service providers. In particular, since the outbreak, travellers are very anxious and any consideration shown to them by hoteliers could build the relationship between the customer and the organisation. This could be more effective in peer-to-peer accommodation businesses after the start of the global pandemic disruption when customers are under enormous pressure and highly vulnerable. Hence, successful service recovery strategies have been found to improve customer satisfaction, positive WOM, repurchase intention and income margins (Migacz et al. 2018; Swanson and Hsu 2011). It has also been found that exceptionally powerful recovery can increase brand reputation (Foroudi et al. 2020a, b, c). However, in the new normal and after critical moments, when the peer-to-peer accommodation businesses melt down significantly, the service recovery strategies such as compensation, apology and peer’s voice are at the heart of the recapture and bouncing back of the industry (Truong et al. 2023).

2.2 The e-service failure and its instigating elements: e-service provider failure, e-payment system failure, peer-to-peer accommodation platform failure, high switching cost

E-service provider failure is the first important element of e-service failure. The service provider is an organisational format that determines dealings among diverse activities, rules, regulations, responsibilities and has the power to carry out different tasks (Balaji et al. 2017). E-Service failure is a significant issue, particularly in the service context where failures happen more regularly (Zourrig et al. 2014). The greater the seriousness of a failure, the lower the general fulfilment will be (Foroudi et al. 2020a, b, c). The gravity of the situation appears to influence the attribution of blame; the more serious the failure, the more the customer will blame the providers (Grewal et al. 2008; Laufer et al. 2005). The seriousness of the service failure can impact the sort of recovery necessary to improve the customer’s disappointment and innovation strategies and performance (Shaik et al. 2023). For example, a customer is bound to anticipate some return from the service provider if the failure involves a monetary issue (McCollough 2009). However, if the service failure appears to be fairly serious, even when the service provider starts a robust service recovery, customers will remain distressed, will engage in negative WOM and will be more averse to building up trust and commitment toward the service provider. Nonetheless, even serious service failure can be forgiven and the customer’s belief can be built again, but this could be highly dependent on the recovery strategy and proposition. Hence, for a speedy recovery from crisis crunches, the e-service provider must act quickly after customer complaints and encourage employees to show moral behaviours to calm the unhappy customers and raise repurchase intentions (Nguyen and McColl-Kennedy 2003).

The e-payment system failure is a critical component of e-service failures within the e-business/e-commerce landscape, where electronic or digital payment serves as a litmus test for security and trust. The reliance on information technology (IT) in daily B2C, B2B, C2B, and C2C transactions underscores the need for trust, security, and reliability in all major forms of electronic payment (Johnson and Grayson 2005). During a global crisis, such as the challenges faced by businesses like Airbnb, the inability to promptly respond and resolve e-payment system failures can have significant implications for customers’ repurchase intentions. The heightened perception of risks, including theft, fraud, and invasion of privacy, intensifies customers’ discomfort in engaging in transactions on open networks.

The third element of e-service failure pertains to peer-to-peer accommodation online platform failures, which are integral to web-based businesses. Customer awareness of website quality directly influences their intention to use the platform (Malhotra et al. 2017). In the context of social media and online service failures, websites become a crucial variable driving customers’ repurchase intentions (Vázquez-Casielles et al. 2017). Notable platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, MySpace, Plurk, Yelp, and Tripadvisor enable service providers to rapidly gather a substantial pool of potential feedback from customers, aiding in the improvement of service and recovery strategies (Weitzl and Hutzinger 2017). Website administrators are increasingly expanding online capacity and promoting internet-based purchasing on their platforms (Jung and Seock 2017). However, the overuse of online services heightens the likelihood of e-system failures, presenting challenges for organizations. Kuo and Wu (2012) emphasize that website quality and design significantly impact customers’ intentions to reuse the website and repurchase products or services. Approximately 49.4% of the variance in customers’ reuse intention can be explained by the quality of website design (McCoy et al. 2009). Customers who perceive a website as high quality are more likely to reuse it than those who perceive it as lower quality (Jung and Seock 2017; Malhotra et al. 2017). However, during a global crisis, customers may require additional assurances related to specific aspects, such as hygiene and health during the Covid-19 outbreak, from service providers. This includes a commitment to quality website design to bolster customers’ repurchase intentions. In conclusion, addressing e-service failures, particularly e-payment system and online platform failures, necessitates a comprehensive approach that integrates knowledge management and change management strategies. Such an approach is crucial for building and maintaining customer trust and loyalty during both normal operations and times of crisis.

The high switching cost is the final cause of e-service failure. Switching costs are incurred by a customer changing from one supplier to another supplier (Chakravarty 2014; Wang et al. 2011), from one product to another (Lee and Youn 2009) or from one brand to another brand and include time-based switching costs (Stauss and Friege 1999). Types of switching costs include exit fees, equipment fees, economic risk, community risk etc. (Hafeez et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2011). Switching costs are the customer’s impression of the money, time and difficulty related to changing service providers, and reduce the likelihood of customers wishing to switch. The Switching costs can lead to customers feeling trapped and can amplify their anger and dissatisfaction when they encounter weak recovery (Haj-Salem and Chebat 2014; Jones et al. 2000). The switching costs are directly associated with repurchase intentions; they are probably related to negative emotions since they interfere with customers’ eagerness to give up the association (Keller 2016). The concept of e-service failure and crisis times entails the comprehensive necessity of recovery strategy, and service providers become more concerned about customers’ satisfaction through avoidance of service failure.

3 Hypotheses development

The success of services like Airbnb, Blablacar, and Shpock demonstrates a move from an ownership to a sharing society (Clauss et al. 2019). According to sharing economy paradigm, peer-to-peer-based services allow users to obtaining, giving, or sharing the access to goods and services, coordinated through community-based online platforms (Hamari et al. 2016; Richter et al. 2017). Home sharing and peer-to-peer accommodation e-services, in particular, are transforming tourism industry (Chen and Tussyadiah 2021). In a peer-to-peer accommodation system, travellers must interact with two different agents: (1) the platform provider, who facilitates online exchange, and (2) the peer provider, who provides real service both online and offline (Benoit et al. 2017).

During critical times the breakdown of the service has led to the disconfirmation of service expectations and, in turn, to an outcome service failure. Outcome failure occurs when a service provider fails to execute the core service or meet the basic demands of the clients (an unavailable service) (Hoffman and Chung 1999). In this vein, service providers should identify the most advantageous techniques to service recovery in order to improve customer satisfaction and the customer-service provider relationship (Swanson and Hsu 2009, Huarng and Yu 2019).

An effective recovery strategy may avoid unfavourable effects such as online clients switching service providers, resorting to an interpersonal delivery option, or even deciding to discontinue use of the internet entirely. It can also boost loyalty-related behavioural intentions, such as repurchase intentions and positive word-of-mouth.

In this scenario the conceptual model for this study shows how peers are likely to react to e-service failure. The vast majority of customers may move beyond their disappointment and exit the relationship and switch providers or become suspicious of future interactions (Obeidat et al. 2017). Peers whose emotional response to a service experience is negative may choose to complain to the online platform. Prior studies (Ozuem and Azemi 2018; Li and Stacks 2017; Obeidat et al. 2018 full reference required) have shown that insufficient responses to complaints or customer feelings of helplessness or anger, result in the customers ending the relationship or implementing negative WOM (Gelbrich 2010) or revengeful behaviours (Joireman et al. 2013; Obeidat et al. 2017; Zourrig et al. 2009).

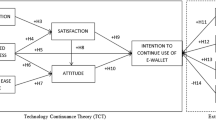

The conceptual model indicates the relationship between e-service failure and peers’ attitudes in the sharing-economy industry after moments of disruption. Furthermore, it shows that based on the fairness theory there is a direct link between peers’ attitudes and the proposed resolution offered (compensation, apology, peer’s voice), future intentions and relationship termination. When e-service failure happens, some customers may be happy with the resolution by the company, which impacts their future intentions or relationship termination where they may switch to another competitor. This relationship termination is the outcome of the justice theory. In addition, to understand the perception or inference of cause and how the individual behaves, attribution theory was employed (Folkes 1984; Mizerski et al. 1979; Kelley and Michela 1980). This study shows a number of positive consequences that can be achieved from resolution strategies offered by the company, such as improved repurchase intention, reduced switchover intentions and post-recovery satisfaction (Fig. 1).

3.1 Relationship between e-service failure and peers’ attitudes

E-service failure is seen as a huge determinant of customer dissatisfaction and switching behaviours (Bambauer-Sachse and Rabeson 2015; Varela-Neira et al. 2010), when customers are already dealing with a high level of negative emotion and disappointments. Mostly, in the case of e-service failure, the customer anticipates receiving compensation for the inconvenience (Rasoulian et al. 2017) such as refunds, credits, promotions, discounts and apologies. A large number of studies have recognised that service failures result in major negative outcomes such as customer negative WOM, publicly expressed dissatisfaction and switching to a competitor. Other researchers (Crisafulli and Singh 2017; Obeidat et al. 2018) have demonstrated that the more serious the service failure, the more negative the customer feels towards the e-service provider. Moreover, the customer typically feels more suffering than gain after each service failure, regardless of the e-service provider’s recovery efforts (Tran et al. 2016), and this is the case after the global crisis times. E-service failure has negative effects on associations between customers as well as with service providers (Casidy and Shin 2015). Customers who experience serious failures are probably going to recognise bigger losses, assess the service negatively and make statements of dissatisfaction. They are likely to show dislike of the idea of having an ongoing connection with the firm and to engage in negative WOM towards the service provider (Sengupta et al. 2015). Additionally, serious failures may escalate revengeful behaviours and feelings (Bonifield and Cole 2007), particularly after the Covid-19 pandemic when customers are very sensitive and worried about uncertainty.

To understand how the e-service failure affects the peer’s attitude, the attribute theory helps social psychologists to recognise how individuals make sense of their life and the world (Weiner 1986). The attribution theory refers “to the perception or inference of cause” (Kelley and Michela 1980) and how individuals thrive or fail in active communications and what causes the particular behaviors (Kelley and Michela 1980). The attribution theory has been significantly used in various domains such as marketing and consumer behaviour studies (Folkes 1984; Mizerski et al. 1979). It specifies the consumers’ possibility of pleasure, perceptive, emotion, and behaviour (Weiner 2000). Considering that attribution theory indicates that an individuals’ perception about the others’ failure or success can be attributed to another individual’s behaviour (Weiner 1986). In this study, by focusing on attribution theory we explore further the consumers’ decision-making process (Mizerski et al. 1979) after e-service failure in the new normal (Cuomo et al. 2021).

Perceived betrayal is a potential emotion that emerges in a service failure situation (Obeidat et al. 2017) which influences customers’ attitudes. This emotion is probably going to guide the assessment of adapting potential behaviour before customers engage in encounters and negative WOM (Berger 2014). Perceived betrayal happens when people feel that the standard of a social relationship is damaged (Gregoire and Fisher 2008). In contrast with simply dissatisfied customers who may look for change, individuals who feel betrayed are more likely to seek both compensation and revenge (Obeidat et al. 2017; Zeelenberg and Pieters 2004). An empirical investigation by previous scholars (Gregoire and Fisher 2008; Hogreve et al. 2017; Obeidat et al. 2017) established that perceived betrayal improved customers’ disciplinary behaviours which moderate between service failure and attitude. Thus, we propose that service failure affects the customer’s attitude as follows:

-

H1: Service failure has a negative impact on the peer’s attitude

-

H1a: Perceived betrayal due to the global health crises has positive impacts on the relationships between service failure and customers’ attitudes.

3.2 Relationship between peers’ attitudes and peers’ expectations on the proposed resolution

Attitudes act as a bridge between emotions and beliefs (Bambauer-Sachse and Rabeson 2015; Estrada et al. 2018; Ozkan-Tektas and Basgoze 2017). In this study, we identified four key elements of attitude: (i) judgement which could be referred to as blame and morale (ii) behavioural attitude which relates to anger, negative word of mouth and avoidance, (iii) dis/satisfaction and (iv) negative emotions. In service failure circumstances, customers do not experience positive emotions. Negative emotions and attitudes have been broadly researched to clarify customer responses to service failures (Gregoire et al. 2009; Mattila and Ro 2008; Zeelenberg and Pieters 2004). Negative emotions such as anger, revenge, dissatisfaction, negative WOM and intention to complain can be grouped into a single measurement (Varela-Neira et al. 2010). The effect of negative emotions is that customers experience negative attitudes when they experience service failure (Cho et al. 2017; Jean Harrison-Walker 2012; Zeelenberg and Pieters 2004). Customers who experience dissatisfaction might feel they should have selected other service providers capable of delivering a superior service (Balaji et al. 2017; Cho et al. 2017; Li et al. 2016; Su and Teng 2018), although this may not be true in the case of the crisis times.

Many scholars have noted that the relationship between customers and the service firms affects customers’ responses to e-service failures and recovery offers (Foroudi et al. 2020a, b, c; Kelley and Davis 1994; Su and Teng 2018; Umashankar et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2011). Also, studies by Hoffman et al. (1995; 2016) stated that service failures caused by staff attitudes and behaviour were among the hardest to recover. Furthermore, attitude also takes different forms such as dissatisfaction, regret, disappointment or anger (Li and Stacks 2017). Various emotions lead to changes in behavioural responses (Azemi et al. 2019; 2020; Bougie et al. 2003; Li and Stacks 2017). Amongst all the negative emotions examined in service failure anger, the different situations have been a significant component. According to scholars (Gelbrich and Roschk 2011; Maxham 2001; Smith and Bolton 2002), anger is the strongest emotion that you feel when you think that someone has performed in an unfair, cruel or intolerable way. Anger frequently includes belief and blame that injustice has occurred, which is generally related to behaviour tendencies such as wishing to act violently (Bougie et al. 2003; Li and Stacks 2017). Also, prior studies have established anger as a predictor of revenge behaviours (Gregoire et al. 2009; Li and Stacks 2017; Sánchez-García and Currás-Pérez 2011). Customers who display anger are probably going to engage in responses like direct complaining, negative WOM and exit (Gregoire et al. 2009; Li and Stacks 2017; Mattila and Ro 2008; Sánchez-García and Currás-Pérez 2011; Zhang et al. 2017; Zourrig et al. 2009). After the Covid-19 pandemic, many customers showed anger when they couldn’t get a satisfying response for the service failure due to the global health crises.

Dissatisfaction has received less attention than anger in the literature. It relates to a situation causing unhappiness or the state of being unhappy (Azemi et al. 2019; Zourrig et al. 2014). For instance, dissatisfaction is the attitude shown if a hotel does not meet the degree of service expected (Chen et al. 2018; Weun et al. 2004). Customers’ responses cannot qualify as complying behaviour without perceptions of dissatisfaction (Li 2016). Past studies have specified that in situations of service failure, dissatisfaction can lead customers to exit, complain, spread negative WOM and become involved in third party complaining (Li and Stacks 2017; Bougie et al. 2003; Maxham and Netemeyer 2002a). Avoidance, meanwhile, is more reactive behaviour. The concept of desire for avoidance is related to customers’ requirement to withdraw themselves from any exchanges with companies (Li and stacks 2017; Gregoire et al. 2009) for a reason such as unhappiness, fear and disgrace (Azemi et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2018). Customers with higher avoidance tendencies are less likely to undertake confrontational strategies, for example, direct face-to-face complaining and revenge. Desires for avoidance are not mutually exclusive (Li 2016). People may complain publicly about e-platforms and complain privately to close social ties; both are indirect methods of revenge and much less confrontational than complaining face-to-face (Li and Stacks 2017).

Blame, however, refers to situations in which people say or think that someone or something is wrong or are responsible for something bad happening (Grewal et al. 2008; Laufer et al. 2005). Foroudi et al. (2020a, b, c) noted that when something goes wrong we immediately try to figure out who we can blame. This significantly occurred after the global health crises. Blame attributions assist in forecasting customers’ responses to support after service failures and the ensuing differential results, such as anger, negative WOM and intent to complain (Albrecht et al. 2017; Van Vaerenbergh et al. 2014). In these situations, fair recovery re-establishes or reduces the customer’s reaction to the service failure. Customer satisfaction will depend on the extent to which they feel it has been dealt with through reasonable solutions. If they do not feel they have experienced justice, they may feel their agreement with the service providers has been abused, and there may be additional outcomes that are unhelpful to the service provider such as negative WOM, switching behaviour, boycotting the e-service provider and emotional expelling (Balaji et al. 2015; Gelbrich 2010), where this may lead them to a situation of helplessness.

Helplessness is a negative emotion evoked after evaluation of a stressful service failure episode. It happens when people feel that they cannot change the situation (Obeidat et al. 2017). This may have been the main problem for many Airbnb and hotel peers and customers after the global health crises, where WHO and local governments’ guidelines changed frequently, and uncertainty was at its highest level where customers could not change the objectives. Customers who feel helpless to challenge the service provider directly may engage in harsh negative WOM (Obeidat et al. 2017; Gelbrich 2010; Zhang et al. 2017) and desire for revenge. This behaviour results from the situation where customers feel they cannot change or resolve the situation, either through power or influence (Gelbrich 2010; Jung and Seock 2018; Obeidat et al. 2017). Therefore, focusing on peers’ attitudes in service failure situations concerning peers' expectations of the proposed resolution, the following hypotheses are proposed:

-

H2: Peers’ attitudes have a positive impact on peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution

-

H2a: Helplessness has negative impacts on the relationships between the peers’ attitudes and resolutions offered

-

H2b: WHO have had negative impacts on the relationships between the peers’ attitudes and resolutions offered

-

H3: Peers’ attitudes have negative impacts on relationship termination.

3.3 Relationship between peers’ expectations of a proposed resolution and future intention

Customer’s expectation of the recovery often includes compensation, apology and having their voice heard. The service marketing literature shows that all three of these recovery elements have supportive impacts on post-recovery customer satisfaction in online services, where this positively influences repurchase intention in the online shopping sector (Smith et al. 1999; Tax et al. 1998). Service recovery refers to the activities and actions that an organisation engages in to restore, amend and rectify the loss experienced by customers as a result of inadequacies in service execution (Hess et al. 2003; Migacz et al. 2018). Service recovery impacts a customer’s satisfaction recovery (Varela-Neira et al. 2010). Thus, service recovery and resolution utilise the customer’s social judgement and lead them to repurchase intention (Vázquez-Casielles et al. 2012). Customers will be happy with recovery when they feel that recovery efforts are fair concerning their perceived loss. Lee (2018) acknowledged two kinds of compensation: monetary and non-monetary. Monetary compensation covers promotion, free tickets, gifts, discounts etc., while non-monetary compensation includes apologies and speed of response (Fu et al. 2015; Smith et al. 1999; Wirtz and Mattila 2004). After the COVID-19 pandemic, the combination of monetary and non-monetary compensation may offer the best recovery for the customers and peers.

A blend of reward apology and speed of recovery has a combined effect on recovery happiness (Wirtz and Mattila 2004). In circumstances of negative emotion, the use of a free gift or apology may result in a switch to positive emotion (Golder et al. 2012). Fu et al. (2015) found that combining non-monetary and monetary compensation resulted in higher customer repurchase intention (Lee 2018), an increase in brand reputation and lower switchover intention. Thus, customers’ and peers’ positive attitudes to resolution could have a significant impact on their future intention. However, when customers feel that they do not get a fair recovery in terms of compensation, promotions or apologies, then they may exit (Jung and Seock 2017; Lee 2018; Ozkan-Tektas and Basgoze 2017; Sengupta et al. 2018). It is important to understand, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, what factors in these circumstances contribute to customers’ decisions regarding exit routes, since exit outcomes have significant effects on the entrepreneur, company, competitive market dynamics and economics through the redeployment of resources (Wennberg et al. 2010). Moreover, the customers’ exit can express a negative WOM and negative emotion and disconnect them from the service provider. Therefore, it was hypothesised that peers’ expectations of the recovery offer or proposed resolution affects their future intention and relationship termination as follows:

-

H4: Peers’ expectations of a proposed resolution have positive impacts on their future intention.

-

H4a: Peers’ positive attitudes to resolution have a positive impact on the relationship between peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution and future intention.

-

H5: Peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution have negative impacts on peers’ relationship termination.

4 Research methods

4.1 Sampling and data collection

The research sample was drawn from Airbnb peers which is the first global online market for primarily homestays, vacation rentals, tourism activities, and lodging. To gauge peers’ perception of the effect of the e-service failure after the global health disruption on recovery strategy from Airbnb peers, a self-administrated questionnaire was distributed. A questionnaire was distributed via an online link employing a convenience and non-random sampling technique (Bell and Bryman 2007) over a six-week period. A convenience sample was used to reduce the potential bias in terms of the generalizability and validity of the research scales. A total of 404 usable data were received (Table 1).

4.1.1 Variables and measurement

Before collecting data, we have collected 17 interviews with the Airbnb peers and university faculties who are experts in the field. The content domain was designed based on the related literature and interviews which were employed in the main survey (Churchill 1979). The data triangulation improved the richness of the study conclusion and results in validity. Based on the literature review and qualitative data, we developed a large pool of multi-item scale measurements for each construct (Churchill 1979). In order to satisfy the content validity of the measurement items, six academics in the hospitality and marketing department who are familiar with the topic, as well as managers and consultants, were enlisted to measure the items (Zaichkowsky 1985). They were focused on removing unessential measures so to make sure that the items were representative of the scale measurement (Foroudi 2019; 2020).

There are five main constructs in the current research: (i) e-service failure after the global health crises, (ii) peers’ attitudes, (iii) peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution, (iv) future intention and (v) relationship termination. (i) E-service failure after the global health disruption was measured through four components: (a) e-service providers’ failure (Baker and Kim 2018; Wirtz and Mattila 2003), (b) e-payment system failure (Holloway and Beatty 2003; Tarafdar and Zhang 2005; 2008; Wolfinbarger and Gilly 2003), (c) peer-to-peer accommodation platform failure (Barreda et al. 2016; Casaló et al. 2010; Crisafulli and Singh 2017; Fuentes-Blasco et al. 2010; Holloway and Beatty 2003), and (d) high switching costs (Chen and Chang 2008). (ii) The peers’ attitudes were measured via four components: (a) negative emotions (Crisafulli and Singh 2017), (b) satisfaction (Boshoff and Allen 2000; Sengupta et al. 2015), (c) behavioural attitude, which was examined via three components: anger (Albrecht et al. 2017; Gelbrich 2010), negative WOM (Albrecht et al. 2017; Chen et al. 2018; Gelbrich 2010; Israeli et al. 2019; Lee and Cranage 2017) and avoidance (Boshoff and Allen 2000; Sengupta et al. 2015), (d) judgmental attitude, which was examined based on morale (Chen et al. 2018; Maher and Singhapakdi 2017) and blame (Lee and Cranage 2017). (iii) To measure peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution, we used compensation (Gelbrich 2010; McCollough et al. 2000), apology (Boshoff 1999) and voice (Rusbult et al. 1988). (iv) Future intention consists of two key elements: (a) intent to repurchase (Chen et al. 2018; Hazee et al. 2017; Maher and Singhapakdi 2017; Vázquez-Casielles et al. 2017; Zeithaml et al. 1996) and (b) switch over intention (Umashankar et al. 2017). (v) Relationship termination was measured by exit (Davis-Blake et al. 2003) and detachment due to lockdown anxiety (Perrin-Martinenq 2004). In this study, we identified the four key moderators’ helplessness after the global health crisis (Gregoire and Fisher 2008; Obeidat et al. 2017), perceived betrayal due to the pandemic (Gregoire and Fisher 2008; Obeidat et al. 2017), WHO/government outbreak guidelines and positive attitude towards resolution (Jiang and Wen 2020). Appendix Table 4 illustrates the study constructs and scale items. The items were tested by 121 academics (doctoral researchers and lecturers) and Airbnb peers. The pre-test participants were not invited to participate in the main study. The data was assessed via EFA (exploratory factor analysis) to recognise any patterns in the data and reduce the item measurements. Some items with a correlation of less than 0.5 and multiple loadings on two factors were removed. The scale illustrated a high degree of reliability with Cronbach’s α of 0.8 (Hair et al. 2006).

4.2 Data analysis

In accordance with the recommendation by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), this research employed a measure validation procedure via a two-step approach based on mixed methods (Kidder and Fine 1987; Gilad 2021; Talwar et al 2021). The data was analysed by using analysis of moment structures (AMOS 25) by employing the default method – Maximum Likelihood (ML). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to measure the construct uni-dimensionality.

5 Results

The results show the examination of each item was internally consistent (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). Moreover, relationships among the study factors were less than the recommended value of 0.92, and there were no concerns of discriminant validity (Kline 2005). The homogeneity of the construct was inspected by convergent validity (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) was assessed, and a good rule of thumb was higher than indicates adequate convergent validity ranging from 0.689 to 0.959 (Table 2). The results of goodness-of-fit indices show a satisfactory fit to the data (RMSEA- Root mean square error of approximation = 0.051; CFI- Comparative fit index = 0.954; TLI–Tucker-Lewis index = 0.947; IFI–Incremental Fit Index = 0.954; Normed fit index-NFI = 0.915).

To test the hypotheses using all available observations, the model fit was assessed for overall fitness by referring to the fit indices as recommended by Hair et al. (2006) and Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, 0.055 < 0.08) and CFI (0.941 > 0.90), TLI (0.938 > 0.90) and IFI (0.941 > 0.90) offer adequate unique information to assess a model (Hair et al. 2006) and therefore indicate the uni-dimensionality of the measures (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). The final study model with structural path coefficients and t-values for each relationship and with squared multiple correlations (R2) for each endogenous construct are illustrated in Table 3.

Hypothesis 1, proposing the direct effect of the e-service failure on peers’ attitudes after the health disruption (H1: β = 1.244, t = 5.701), was statistically supported. H2 and H3 address the impact of peers’ attitudes on peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution and relationship termination (β = 0.589, t = 8.931; β = 0.210, t = 2.746, respectively). The findings signify that the relationship between peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution and future intention (H4) was significant (β = 1.019, t = 9.289). Concerning the research hypothesis H5, the result shows the relationship between peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution and relationship termination (β = 0.601, t = 5.615) was also significant. Also, the results show that perceived betrayal due to the pandemic dampens the positive relationship between e-service failure after the global health disruption and peers’ attitudes. Also, helplessness after global health crises dampens the positive relationship between peers’ attitudes and peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution. In addition, WHO dampen the positive relationship between peers’ attitudes and peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution. Finally, a positive attitude to resolution dampens the positive relationship between peers’ expectations of the proposed resolution and future intention (Fig. 2).

6 Discussion

Based on the qualitative and quantitative analysis, this research leads service providers and academics to better understand the problems of service failure in the online shopping sector.

6.1 Theoretical implications

This research contributes based on the relationship between e-service failure and recovery strategies after crisis times. This study will improve the understanding of recovery strategies for online service providers in peer-to-peer accommodation. Managers and service providers may need to focus further on the quality of recovery strategies by providing prompt support to enhance peers’ satisfaction. This could be implemented efficiently via the platform of social media. Some scholars have suggested that a firm’s social media presence must be capable of recognising and assessing customers’ needs in failure recovery (Ozuem and Azemi 2018). Moreover, timely recovery is one of the most important elements of recovery systems, particularly in peer-to-peer online service failures, where peers can effortlessly register an objection by phone or email, and service providers might require time to examine online service issues. This study makes significant contributions to the understanding of customers’ use of technology in the case of e-service failure, particularly for negative WOM, negative emotions, anger, avoidance and dissatisfaction, where they want their voice to be heard.

This study provides theoretical implications for global hospitality and future research. Academics should investigate further the better use of AI for service delivery, formation and communication at hotels (Huang and Rust 2021) and in the sharing-economy industry. The crises times has shown the value of nature and the environment to people (Zhou et al. 2020) and this moves the tourism industry more towards eco-tourism and slow tourism (Oh et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2017). Hence, future studies need to focus more on sustainable tourism with efficient integration into artificial intelligence (AI). In this last direction, future research should explore how AI can be effectively utilized for more resilient and efficient recovery systems (Bogoviz 2020).

At least, the theoretical implications underscore the significance of integrating knowledge management and change management principles for the development of effective recovery strategies in the peer-to-peer accommodation sector. This involves leveraging technology, particularly social media and AI, and embracing sustainable practices in the evolving landscape of online services.

6.2 Managerial implications

This study offers valuable insights with significant managerial implications, providing stakeholders in the marketplace with innovative ideas and strategies to navigate service failures in the online domain, especially in the aftermath of global health crises. The research contributes to an enhanced understanding of managerial practices concerning service failure recovery and aims to guide the enhancement of customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions within the realm of crisis management, innovation failure and knowledge management (Long et al. 2024). Furthermore, this research suggests that peer-to-peer accommodation should develop in the digital marketing sector (Mele et al. 2024), which would increase their attendance on social media platforms and offer a means to control e-customer communication through recovery strategies.

After the start of the global health crises and disruption, when there is a high expectation of service failure, peers have become increasingly anxious and more sensitive to service failure. Following the onset of global health crises, heightened expectations of service failures have made peers more sensitive and anxious. Recognizing this, online service providers should approach recovery efforts with meticulous attention to formulation, understanding the challenges posed by increased peer sensitivity.

This study shows that when a peer-to-peer accommodation (e.g., Airbnb) service provides a mistake, careful attention should be paid to the formulation of recovery efforts. The recovery strategy must be seen as a fair strategy for peers and for the service providers in line with the fairness theory, to result in both parties being satisfied. However, achieving a satisfactory attitude after the e-service failure, particularly after the world health crises, would be very challenging for peers and it may require a more lagged strategy to promise fairness. The global uncertainty merged with ongoing and vague health crises has caused service providers such as Airbnb to face a lot of difficulty in providing successful recovery strategies. This study suggests that online service providers need to consider both the fairness theory and justice theory when they plan service resolution policies and procedures, with the aim of achieving prompt recovery. Principally, after the global health crises, this article will help practitioners to understand that efficient online service resolution will create a scope of positive peers’ responses as a key component in e-service recovery in sharing-economy businesses (Papa et al. 2022) and strategies. Responding competently to online peers’ complaints can have a significant impact on peers’ satisfaction, online repurchase intentions and the spread of word-of-mouth through online platforms and social media.

6.3 Limitations and future suggestions

Our study is subject to some limitations which provide further opportunities for future research. Future studies could examine the effects of global health crises on e-service failure in different sectors such as the transport sector, in particular, Uber. In addition, this study concentrated on UK peer-to-peer accommodation businesses, whereas future studies could focus on different countries and compare the results with this study to recognise an efficient strategy based on the attribution theory, justice theory and fairness theory to enhance e-service recovery and encourage customers repurchase intentions with sharing-economy in different countries. Furthermore, customers’ reactions to e-service failure via social media could be reflected by their past experience with the particular service provider and answering to crisis managerial solutions. A future recommendation could be for this to be explored further. Moreover, future research is encouraged to conduct data from different industries and compare the results with our study.

Data availability

None.

References

Abbas J, Khan SM (2023) Green knowledge management and organizational green culture: an interaction for organizational green innovation and green performance. J Knowl Manag 27(7):1852–1870

Albrecht AK, Walsh G, Beatty SE (2017) Perceptions of group versus individual service failures and their effects on customer outcomes: the role of attributions and customer entitlement. J Serv Res 20(2):188–203

Alguacil M, González-Serrano MH, Gómez-Tafalla AM, González-García RJ, Aguado-Berenguer S (2021) Credibility to attract, trust to stay: the mediating role of trust in improving brand congruence in sports services. Eur J Int Manag 15(2–3):231-246

Anand A, Shantakumar VP, Muskat B, Singh SK, Dumazert JP, Riahi Y (2022) The role of knowledge management in the tourism sector: a synthesis and way forward. J Knowl Manag 27(5):1319–1342

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modelling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411–423

Azemi Y, Ozuem W (2016) Online service failure and recovery strategy: the mediating role of social media. In: Competitive social media marketing strategies, pp 112–135. IGI Global

Azemi Y, Ozuem W, Howell KE (2020) The effects of online negative word-of-mouth on dissatisfied customers: a frustration–aggression perspective. Psychol Mark 37(4):564–577

Azemi Y, Ozuem W, Howell KE, Lancaster G (2019) An exploration into the practice of online service failure and recovery strategies in the Balkans. J Bus Res 9(Jan):420–431

Baker MA, Kim K (2018) Other customer service failures: emotions, impacts, and attributions. J Hospit Tourism Res 42(7):1067–1085

Balaji MS, Jha S, Royne MB (2015) Customer e-complaining behaviours using social media. Serv Ind J 35(11–12):633–654

Balaji MS, Roy SK, Quazi A (2017) Customers’ emotion regulation strategies in service failure encounters. Eur J Mark 51(5/6):960–982

Bambauer-Sachse S, Rabeson L (2015) Determining adequate tangible compensation in service recovery processes for developed and developing countries: the role of severity and responsibility. J Retail Consum Serv 22(Jan):117–127

Barreda AA, Bilgihan A, Nusair K, Okumus F (2016) Online branding: development of hotel branding through interactivity theory. Tour Manag 57(Dec):180–192

Bell E, Bryman A (2007) The ethics of management research: an exploratory content analysis. Br J Manag 18(1):63–77

Benoit S, Baker TL, Bolton RN, Gruber T, Kandampully J (2017) A triadic framework for collaborative consumption (CC): Motives, activities and resources & capabilities of actors. J Bus Res 79:219–227

Berger J (2014) Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: a review and directions for future research. J Cust Psychol 24(4):586–607

Bitner MJ, Booms BH, Tetreault MS (1990) The service encounter: diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. J Mark 54(1):71–84

Bogoviz AV (2020) Perspective directions of state regulation of competition between human and artificial intellectual capital in Industry 4.0. J Intell Cap 21(4):583–600

Bonifield C, Cole C (2007) Affective responses to service failure: anger, regret, and retaliatory versus conciliatory responses. Mark Lett 18(1–2):85–99

Boshoff C (1999) Recovsat: an instrument to measure satisfaction with transaction-specific service recovery. J Serv Res 1(3):236–249

Boshoff C, Allen J (2000) The influence of selected antecedents on frontline staff’s perceptions of service recovery performance. Int J Serv Ind Manag 11(1):63–90

Bougie R, Pieters R, Zeelenberg M (2003) Angry customers don’t come back, they get back: the experience and behavioral implications of anger and dissatisfaction in services. J Acad Mark Sci 31(4):377–393

Callarisa-Fiol LJ, Moliner-Tena MÁ, Rodríguez-Artola R, Sánchez-García J (2023) Entrepreneurship innovation using social robots in tourism: a social listening study. Rev Manag Sci 1–27

Casaló LV, Flavián C, Guinalíu M (2010) Determinants of the intention to participate in firm-hosted online travel communities and effects on consumer behavioral intentions. Tour Manage 1(6):898–911

Casidy R, Shin H (2015) The effects of harm directions and service recovery strategies on customer forgiveness and negative word-of-mouth intentions. J Retail Cust Serv 27(Nov):103–112

Chakravarty AK (2014) Managing suppliers. In: Supply chain transformation. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 89-128

Chan ES, Lam D (2013) Hotel safety and security systems: bridging the gap between managers and guests. Int J Hosp Manag 32(March):202–216

Chan JFW, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KKW, Chu H, Yang J, Tsoi HW (2020) A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet 395(10223):514–523

Chen MH (2011) The response of hotel performance to international tourism development and crisis events. Int J Hosp Manag 30(1):200–212

Chen CF, Chang YY (2008) Airline brand equity, brand preference, and purchase intentions—The moderating effects of switching costs. J Air Transp Manag 14(1):40–42

Chen Y, Tussyadiah IP (2021) Service failure in peer-to-peer accommodation. Ann Tour Res 88:103156

Chen T, Ma K, Bian X, Zheng C, Devlin J (2018) Is high recovery more effective than expected recovery in addressing service failure? A moral judgment perspective. J Bus Res 82(Jan):1–9

Cho SB, Jang YJ, Kim WG (2017) The moderating role of severity of service failure in the relationship among regret/disappointment, dissatisfaction, and behavioral intention. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 18(1):69–85

Choi S, Mattila AS (2008) Perceived controllability and service expectations: influences on customer reactions following service failure. J Bus Res 61(1):24–30

Churchill GA Jr (1979) A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J Mark Res 16(1):64–73

Clauss T, Harengel P, Hock M (2019) The perception of value of platform-based business models in the sharing economy: determining the drivers of user loyalty. RMS 13:605–634

Colgate M, Tong VTU, Lee CKC, Farley JU (2007) Back from the brink: why customers stay. J Serv Res 9(3):211–228

Courtney D, Watson P, Battaglia M, Mulsant BH, Szatmari P (2020) COVID-19 impacts on child and youth anxiety and depression: challenges and opportunities. Can J Psychiatry 65(10):688–691

Crisafulli B, Singh J (2017) Service failures in e-retailing: examining the effects of response time, compensation, and service criticality. Comput Hum Behav 77(Dec):413–424

Cuomo MT, Tortora D, Danovi A, Festa G, Metallo G (2021) Toward a ‘new normal’? Tourist preferences impact on hospitality industry competitiveness. Corp Reput Rev 1–14

Curran L, Eckhardt J (2021) Why COVID-19 will not lead to major restructuring of global value chains. Manag Organ Rev 17(2):407–411

Dalwai T, Sewpersadh NS (2023) Intellectual capital and institutional governance as capital structure determinants in the tourism sector. J Intellect Cap 24(2):430–464

Davis-Blake A, Broschak JP, George E (2003) Happy together? How using nonstandard workers affects exit, voice, and loyalty among standard employees. Acad Manag J 46(4):475–485

Detert JR, Burris ER (2007) Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manag J 50(4):869–884

Duan Y, Yang M, Liu H, Chin T (2023) How does digital transformation affect innovation in knowledge-intensive business services firms? The moderating effect of R&D collaboration portfolio. J Knowl Manag

Emami A, Ashourizadeh S, Sheikhi S, Rexhepi G (2022) Entrepreneurial propensity for market analysis in the time of COVID-19: benefits from individual entrepreneurial orientation and opportunity confidence. RMS 16(8):2413–2439

Estrada A, Batanero C, Díaz C (2018) Exploring teachers’ attitudes towards probability and its teaching. In: Teaching and learning stochastics. Springer, Cham, pp 313–332

Farmaki A, Miguel C (2022) Peer-to-peer accommodation in Europe: trends, challenges and opportunities. In: Česnuitytė V, Klimczuk A, Miguel C, Avram G (eds) The sharing economy in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86897-0_6

Felicetti AM, Corvello V, Ammirato S (2023) Digital innovation in entrepreneurial firms: a systematic literature review. Rev Manag Sci 1–48

Folkes VS (1984) Consumer reactions to product failure: an attributional approach. J Consum Res 10(4):398–409

Foroudi P (2019) Influence of brand signature, brand awareness, brand attitude, brand reputation on hotel industry’s brand performance. Int J Hosp Manag 76(Jan):271–285

Foroudi P (2020) Corporate brand strategy: drivers and outcomes of hotel industry’s brand orientation. Int J Hosp Manag 88(July):102519

Foroudi P, Marvi R (2020) Some like it hot: the role of identity, website, co-creation behavior on identification and love. Eur J Int Manag

Foroudi P, Cuomo MT, Foroudi MM (2020a) Continuance interaction intention in retailing: relations between customer values, satisfaction, loyalty, and identification. Inf Technol People 33(4):1303–1326

Foroudi P, Kitchen PJ, Marvi R, Akarsu TN, Uddin H (2020b) A bibliometric investigation of service failure literature and a research agenda. Eur J Mark 54(10):2575–2619. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-07-2019-0588

Foroudi P, Kitchen PJ, Marvi R, Akarsu TN, Udon H (2020c) A bibliometric investigation of service failure literature and a research agenda. Eur J Mark

Foroudi P, Tabaghdehi SAH, Marvi R (2021) The gloom of the COVID-19 shock in the hospitality industry: a study of consumer risk perception and adaptive belief in the dark cloud of a pandemic. Int J Hosp Manag 92:102717

Fu H, Wu DC, Huang SS, Song H, Gong J (2015) Monetary or nonmonetary compensation for service failure? A study of customer preferences under various loci of causality. Int J Hosp Manag 46(April):55–64

Fuentes-Blasco M, Saura IG, Berenguer-Contri G, Moliner-Velazquez B (2010) Measuring the antecedents of e-loyalty and the effect of switching costs on website. Serv Ind J 30(11):1837–1852

Garau-Vadell JB, Orfila-Sintes F, Batle J (2021) The quest for authenticity and peer-to-peer tourism experiences. J Hosp Tour Manag 47:210–216

Gelbrich K (2010) Anger, frustration, and helplessness after service failure: coping strategies and effective informational support. J Acad Mark Sci 38(5):567–585

Gelbrich K, Roschk H (2011) A meta-analysis of organizational complaint handling and customer responses. J Serv Res 14(1):24–43

Gilad S (2021) Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods in pursuit of richer answers to real-world questions. Public Perform Manag Rev 44(5):1075–1099

Golder PN, Mitra D, Moorman C (2012) What is quality? An integrative framework of processes and states. J Mark 6(4):1–23

Gregoire Y, Fisher RJ (2008) Customer betrayal and retaliation: when your best customers become your worst enemies. J Acad Mark Sci 36(2):247–261

Gregoire Y, Tripp TM, Legoux R (2009) When customer love turns into lasting hate: the effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. J Market 73(6):8–32

Grewal D, Roggeveen AL, Tsiros M (2008) The effect of compensation on repurchase intentions in service recovery. J Retail 84(4):424–434

Hafeez K, Alghatas FM, Foroudi P, Nguyen B, Gupta S (2018) Knowledge sharing by entrepreneurs in a virtual community of practice (VCoP). Inf Technol People 32(2):405–429

Hair JF, William C, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL (2006) Multivariate data analysis. Pearson, New Jersey

Haj-Salem N, Chebat JC (2014) The double-edged sword: the positive and negative effects of switching costs on customer exit and revenge. J Bus Res 67(6):1106–1113

Hamari J, Sjöklint M, Ukkonen A (2016) The sharing economy: why people participate in collaborative consumption. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 67(9):2047–2059

Hazee S, Van Vaerenbergh Y, Armirotto V (2017) Co-creating service recovery after service failure: the role of brand equity. J Bus Res 74(May):101–109

Hess RL Jr, Ganesan S, Klein NM (2003) Service failure and recovery: the impact of relationship factors on customer satisfaction. J Acad Mark Sci 1(2):127–145

Hoffman KD, Chung BG (1999) Hospitality recovery strategies: customer preference versus firm use. J Hosp Tour Res 23(1):71–84

Hoffman KD, Kelley SW, Rotalsky HM (1995) Tracking service failures and employee recovery efforts. J Serv Mark 9(2):49–56

Hoffman KD, Kelley SW, Rotalsky HM (2016) Retrospective: tracking service failures and employee recovery efforts. J Serv Mark 30(1):7–10

Hogreve J, Bilstein N, Mandl L (2017) Unveiling the recovery time zone of tolerance: when time matters in service recovery. J Acad Mark Sci 45(6):866–883

Hoisington A (2020) Insights about how the COVID-19 pandemic will affect hotels”, available at: www.hotelmanagement.net/own/roundup-5-insights-about-how-covid-19-pandemic-will-affect-hotels

Holloway BB, Beatty SE (2003) Service failure in online retailing: a recovery opportunity. J Serv Res 6(1):92–105

Hong JY, Lee WN (2005) Customer complaint behavior in the online environment. In Web systems design and online customer behavior. IGI Global, USA, pp 90–106

Huang M-H, Rust RT (2021) Engaged to a Robot? The Role of AI in Service. J Serv Res 24(1):30–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520902266

Huarng KH, Yu MF (2019) Customer satisfaction and repurchase intention theory for the online sharing economy. RMS 13:635–647

Israeli AA, Lee SA, BoldenIII EC (2019) The impact of escalating service failures and internet addiction behavior on young and older customers’ negative eWOM. J Hosp Tour Manag 39(June):150–157

Issah WB, Anwar M, Clauss T, Kraus S (2023) Managerial capabilities and strategic renewal in family firms in crisis situations: the moderating role of the founding generation. J Bus Res 156:113486

Izadi J, Foroudi P, Nazarian A (2021) Into the unknown: impact of Coronavirus on UK hotel stock performance. Eur J Int Manag. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2022.10059238

Jayawardena C, Tew PJ, Lu Z, Tolomiczenko G, Gellatly J (2008) SARS: lessons in strategic planning for hoteliers and destination marketers. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 20(3):332–346

Jean Harrison-Walker L (2012) The role of cause and effect in service failure. J Serv Mark 26(2):115–123

Jiang Y, Wen J (2020) Effects of COVID-19 on hotel marketing and management: a perspective article. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 32(8):2563–2573

Johnson D, Grayson K (2005) Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. J Bus Res 58(4):500–507

Joireman J, Grégoire Y, Devezer B, Tripp TM (2013) When do customers offer firms a “second chance” following a double deviation? The impact of inferred firm motives on customer revenge and reconciliation. J Retail 89(3):315–337

Jones MA, Mothersbaugh DL, Beatty SE (2000) Switching barriers and repurchase intentions in services. J Retail 6(2):259–274

Jung NY, Seock YK (2017) Effect of service recovery on customers’ perceived justice, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth intentions on online shopping websites. J Retail Cons Serv 37(Jul):23–30

Jung NY, Seock YK (2018) The role of communication channel in delivering service recovery in online shopping environment. Int J Electron Mark Retail 9(1):59–76

Karatepe OM (2006) Customer complaints and organizational responses: the effects of complainants’ perceptions of justice on satisfaction and loyalty. Int J Hosp Manag 25(1):69–90

Kelley HH, Michela JL (1980) Attribution theory and research. Annu Rev Psychol 31(1):457–501

Keller KL (2016) Reflections on customer-based brand equity: Perspectives, progress, and priorities. AMS Rev 6(1–2):1–16

Kelley SW, Davis MA (1994) Antecedents to customer expectations for service recovery. J Acad Mark Sci 22(1):52–61

Kidder LH, Fine M (1987) Qualitative and quantitative methods: when stories converge. New Directions for Program Evaluation 1987(35):57–75

Kim N, Ulgado FM (2012) The effect of on-the-spot versus delayed compensation: the moderating role of failure severity. J Serv Mark 26(3):158–167

Klein A, Horak S, Bacouël-Jentjens S, Li X (2021) Does culture frame technological innovativeness? A study of millennials in triad countries. Eur J Int Manag 15(4):564–594

Kline TJ (2005) Psychological testing: a practical approach to design and evaluation. Sage Publications

Korherr P, Kanbach D (2023) Human-related capabilities in big data analytics: a taxonomy of human factors with impact on firm performance. RMS 17(6):1943–1970

Koronios K, Dimitropoulos P, Kriemadis A, Papadopoulos A (2021) Understanding sport media spectators’ preferences: the relationships among motivators, constraints and actual media consumption behaviour. Eur J Int Manag 15(2–3):174–196

Kuo YF, Wu CM (2012) Satisfaction and post-purchase intentions with service recovery of online shopping websites: Perspectives on perceived justice and emotions. Int J Inf Manage 32(2):127–138

Laufer D, Silver DH, Meyer T (2005) Exploring differences between older and younger consumers in attributions of blame for product harm crises. Acad Mark Sci Rev 1(7):1–21

Lee SH (2018) Guest preferences for service recovery procedures: conjoint analysis. J Hospitality Tour Insights 1(3):276–288

Lee BY, Cranage DA (2017) Service failure of intermediary service: impact of ambiguous locus of control. J Travel Tour Mark 34(4):515–530

Lee M, Youn S (2009) Electronic word of mouth (eWOM) How eWOM platforms influence customer product judgement. Int J Advert 28(3):473–499

Li Z (2016) Psychological empowerment on social media: Who are the empowered users? Public Relat Rev 42(1):49–59

Li ZC, Stacks D (2017) When the relationships fail: a micro perspective on customer responses to service failure. J Public Relat Res 29(4):158–175

Li M, Qiu SC, Liu Z (2016) The Chinese way of response to hospitality service failure: the effects of face and guanxi. Int J Hosp Manag 57(Aug):18–29

Long J, Liu H, Shen Z (2024) Narcissistic rivalry and admiration and knowledge hiding: mediating roles of emotional exhaustion and interpersonal trust. J Knowl Manag 28(1):1–26

Loo PT, Leung R (2018) A service failure framework of hotels in Taiwan: adaptation of 7Ps marketing mix elements. J Vacat Mark 24(1):79–100

Magni D, Papa A, Scuotto V, Del Giudice M (2023) Internationalized knowledge-intensive business service (KIBS) for servitization: a microfoundation perspective. Int Mark Rev 40(4):798–826. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-12-2021-0366

Maher AA, Singhapakdi A (2017) The effect of the moral failure of a foreign brand on competing brands. Eur J Mark 51(5/6):903–922

Malhotra N, Sahadev S, Purani K (2017) Psychological contract violation and customer intention to reuse online retailers: exploring mediating and moderating mechanisms. J Bus Res 75(June):17–28

Mattila AS, Ro H (2008) Discrete negative emotions and customer dissatisfaction responses in a casual restaurant setting. J Hospit Tourism Res 32(1):89–107

Maxham JG III (2001) Service recovery’s influence on consumer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions. J Bus Res 54(1):11–24

Maxham JG III, Netemeyer RG (2002a) A longitudinal study of complaining customers’ evaluations of multiple service failures and recovery efforts. J Mark 66(4):57–71

Maxham JG III, Netemeyer RG (2002b) Modeling customer perceptions of complaint handling over time: the effects of perceived justice on satisfaction and intent. J Retail 78(4):239–252

McCollough MA (2009) The recovery paradox: the effect of recovery performance and service failure severity on post-recovery customer satisfaction. Acad Mark Stud J 13(1):89–104

McCollough MA, Berry LL, Yadav MS (2000) An empirical investigation of customer satisfaction after service failure and recovery. J Serv Res 3(2):121–137

McCoy S, Everard A, Loiacono ET (2009) Online ads in familiar and unfamiliar sites: effects on perceived website quality and intention to reuse. Inf Syst J 19(4):437–458

Mele G, Capaldo G, Secundo G, Corvello V (2024) Revisiting the idea of knowledge-based dynamic capabilities for digital transformation. J Knowl Manag 28(2):532–563. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-02-2023-0121

Melewar TC, Foroudi P, Gupta S, Kitchen PJ, Foroudi MM (2017) Integrating identity, strategy and communications for trust, loyalty and commitment. Eur J Mark 51(3):572–604

Migacz SJ, Zou S, Petrick JF (2018) The “terminal” effects of service failure on airlines: Examining service recovery with justice theory. J Travel Res 57(1):83–98

Mizerski RW, Golden LL, Kernan JB (1979) The attribution process in consumer decision making. J Consum Res 6(2):123–140

Nguyen DT, McColl-Kennedy JR (2003) Diffusing customer anger in service recovery: a conceptual framework. Australas Mark J 11(2):46–55

Obeidat ZMI, Xiao SH, Iyer GR, Nicholson M (2017) Customer revenge using the internet and social media: An examination of the role of service failure types and cognitive appraisal processes. Psychol Mark 34(4):496–515

Obeidat ZM, Xiao SH, Al Qasem Z, Obeidat A (2018) Social media revenge: a typology of online consumer revenge. J Retail Consum Serv 45(Nov):239–255

Oh H, Assaf AG, Baloglu S (2016) Motivations and goals of slow tourism. J Travel Res 55(2):205–219

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020) Rebuilding tourism for the future: COVID-19 policy responses and recovery. OECD Publishing

Ozkan-Tektas O, Basgoze P (2017) Pre-recovery emotions and satisfaction: a moderated mediation model of service recovery and reputation in the banking sector. Eur Manag J 35(3):388–395

Ozuem W, Azemi Y (2018) Online service failure and recovery strategies in luxury brands: a view from justice theory. In: Digital marketing strategies for fashion and luxury brands. IGI Global, pp 108–125

Palos-Sanchez P, Saura JR, Correia MB (2021) Do tourism applications’ quality and user experience influence its acceptance by tourists? RMS 15:1205–1241

Papa A, Mazzucchelli A, Ballestra LV, Usai A (2022) The open innovation journey along heterogeneous modes of knowledge-intensive marketing collaborations: a cross-sectional study of innovative firms in Europe. Int Mark Rev 39(3):602–625

Paraskevas A (2013) Aligning strategy to threat: a baseline anti-terrorism strategy for hotels. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 25(1):140–162

Perrin-Martinenq D (2004) The role of brand detachment on the dissolution of the relationship between the consumer and the brand. J Mark Manag 20(9–10):1001–1023

PwC (2016) Europe’s five key sharing economy sectors could deliver €570 billion by 2025. Retrieved from https://press.pwc.com/News-releases/europe-s-five-key-sharingeconomy-sectors-could-deliver--570-billion-by-2025/s/45858e92-e1a7-4466-a011a7f6b9bb488f

Racherla P, Hu C (2009) A framework for knowledge-based crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 50(4):561–577

Rasoulian S, Grégoire Y, Legoux R, Sénécal S (2017) Service crisis recovery and firm performance: insights from information breach announcements. J Acad Mark Sci 45(6):789–806

Rhaiem K, Amara N (2021) Learning from innovation failures: a systematic review of the literature and research agenda. RMS 15:189–234

Richter C, Kraus S, Brem A, Durst S, Giselbrecht C (2017) Digital entrepreneurship: Innovative business models for the sharing economy. Creat Innov Manag 26(3):300–310