Abstract

Empirical studies on capital structure choice frequently control for whether or not a firm has tax loss carryforwards (TLCFs). However, tax data on TLCFs is often not available to researchers. As a consequence, many studies rely upon earnings-based information in order to determine whether a firm has TLCFs. In this paper, we study the accuracy of earnings-based proxies in predicting whether a firm has TLCFs. Our results, which are based upon a panel of Italian listed firms between 2009 and 2012, show that earnings-based proxies correctly predict whether a firm has TLCFs for 70–77% of all firm-year observations. Furthermore, for all but one proxy, we identify a non-random measurement error in TLCF variables that are built upon these proxies. We evaluate the consequences of this measurement error and find that it does not significantly change the estimated effects of TLCFs on capital structure choice for some proxies, including last year’s earnings before taxes. We conclude that last year’s earnings before taxes serves as an accurate proxy for a firm’s true TLCF status. It is easy to determine and leads to statistically and quantitatively similar conclusions as those reached using tax data on TLCFs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is a general feature of most tax systems that tax losses do not lead to an immediate tax refund but can be used to build up a tax loss carryforward (henceforth: TLCF) that can be offset against positive income in the future. If TLCFs are sufficiently large, they might put firms into a state of tax exemption over several years.Footnote 1 Whether or not a firm has TLCFs is therefore an important variable in regression models that examine tax-related topics, including capital structure choice.Footnote 2 However, due to confidentiality, tax return data on TLCFs is usually not available to empirical tax research.Footnote 3 As a consequence, many studies that analyze capital structure choice rely upon earnings-based information to determine a firm’s TLCF status, that is whether a firm has TLCFs (Bernasconi et al. 2005; Buettner et al. 2009, 2011a, 2011b, 2012, 2016; Buettner and Wamser 2013; Egger et al. 2014; Fossen and Simmler 2016; Haring et al. 2012; Huizinga et al. 2008; Krämer 2015; Overesch and Voeller 2010; Overesch and Wamser 2010, 2014; Pfaffermayr et al. 2013; Rünger et al. 2019; Wamser 2014). In this paper, we study the accuracy of earnings-based TLCF proxies in two ways: First, we examine the accuracy of earnings-based TLCF proxies in identifying the availability of firm-level TLCFs. Second, we study the consequences of measurement error in variables, which are used in regression models on capital structure choice and capture whether a firm has TLCFs (henceforth: TLCF variables).

Theoretical work on the effect of taxes on capital structure choice suggests that firms should prefer debt over equity financing since interest expense on debt is tax deductible, while dividends paid to shareholders are not (Modigliani and Miller 1963).Footnote 4 Only firms with positive taxable income (henceforth: non-TLCF firms) can fully benefit from interest deductions on corporate debt. By contrast, firms with TLCFs (henceforth: TLCF firms) might not be able to immediately benefit from interest deductions on corporate debt since they are already (partially) tax-exempt. Consequently, for TLCF firms, the tax incentive to use debt financing will be smaller than for non-TLCF firms. TLCFs thus act as a substitute for the tax incentive of debt financing (DeAngelo and Masulis 1980). Several empirical studies provide support for this substitution hypothesis (Buettner et al. 2011b; Mackie-Mason 1990; Newberry and Dhaliwal 2001; Trezevant 1992).Footnote 5

Prior research that examines capital structure choice based on US data obtains information on a firm’s TLCF status from data item #52 of the Compustat database (Blouin et al. 2010; Froot and Hines 1995; Graham 1996, 2000; Graham et al. 1998; Kubick et al. 2020; Mackie-Mason 1990; Newberry and Dhaliwal 2001).Footnote 6 Compustat’s data item #52 is defined as the amount of TLCFs reported in a firm’s financial statement and thus reflects a firm’s true TLCF status. As a consequence, these studies do not need to rely upon earnings-based TLCF proxies. Studies based on European data often use other data sources, such as Bureau van Dijk’s Orbis or Amadeus databases or the German MiDi database. These databases do not provide a specific data item that reflects a firm’s true TLCF status. Thus, studies that use these databases cannot directly assess the extent to which a firm has TLCFs but need to proxy for it. Most commonly, these studies use information on past earnings as a proxy for a firm’s TLCF status (Bernasconi et al. 2005; Buettner et al. 2009, 2011a, 2011b, 2012, 2016; Buettner and Wamser 2013; Egger et al. 2014; Fossen and Simmler 2016; Haring et al. 2012; Huizinga et al. 2008; Krämer 2015; Overesch and Voeller 2010; Overesch and Wamser 2010, 2014; Pfaffermayr et al. 2013; Rünger et al. 2019; Wamser 2014).

Regardless of which database is used in capital structure research, TLCF variables should be accurate in identifying whether or not a firm is exposed to TLCFs. If they were not, there would be a bias in descriptive statistics about the number of TLCF firms. Prior research (Max et al. 2021; Plesko 2003) has shown that if measurement error in TLCF variables is non-random, coefficient estimates explaining the impact of TLCFs on tax phenomena would suffer from a downward bias in magnitude. If non-TLCF firms were incorrectly classified as TLCF firms, the possibility to identify any differences in the behavior of TLCF and non-TLCF firms in parametric tests would be reduced. Moreover, if TLCF firms were incorrectly classified as non-TLCF firms, it would be likely to underestimate the response of non-TLCF firms to tax phenomena. As Compustat’s data item #52 truly reflects a firm’s TLCF status, accuracy issues arise in case of coding errors (Heitzman and Lester 2021a; Kinney and Swanson 1993; Max et al. 2021; Mills et al. 2003). The consequences of coding errors on the coefficient estimates for TLCF variables have recently been evaluated by Max et al. (2021), who also provide researchers with a method to estimate values for missing TLCF data. Contrary to Max et al. (2021), we do not study coding issues of existing TLCF information. Rather, we study the consequences of using earnings-based proxies to identify whether a firm has TLCFs if information on true TLCFs is not available to researchers. We therefore provide researchers that cannot assess data on a firm’s true TLCF status with information on the accuracy of earnings-based TLCF proxies and inform about the consequences of using earnings-based TLCF proxies in capital structure research. Importantly, we focus only on the accuracy of earnings-based TLCF proxies in predicting whether or not a firm has TLCFs. We do not examine the extent to which earnings-based TLCF proxies can precisely predict the amount of TLCFs available to a firm.Footnote 7

Niemann and Rechbauer (2013) have evaluated the accuracy of earnings-based TLCF proxies using consolidated earnings to predict whether a firm has TLCFs. By comparing the proxies’ TLCF status predictions to true TLCFs for a sample of Austrian listed groups in 2007 and 2008, Niemann and Rechbauer (2013) find that earnings-based proxies incorrectly predict the availability of TLCFs in 44% to 93% of all cases. The authors point out, however, that the inaccuracy of earnings-based proxies they observe is likely to be overstated given the use of consolidated earnings to determine TLCF status predictions.Footnote 8 TLCFs usually arise and are offset at the firm level.Footnote 9 Consolidated earnings do not inform about earnings realized at the firm level and will therefore be less accurate in identifying the availability of TLCFs.

In this paper, we examine the accuracy of earnings-based proxies using unconsolidated data, i.e., data on firm-level earnings, which we obtain from Bureau van Dijk’s Amadeus database. We first evaluate an earnings-based proxy frequently used in prior research—that is, last year’s earnings before taxes. One conceptual problem with this proxy is that it does not account for differences between tax and GAAP rules (book-tax differences). Therefore, we also examine the accuracy of last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for selected book-tax differences. In particular, we adjust last year’s earnings before taxes for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption or nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier. This allows us to study whether the proxy’s accuracy can be improved by accounting for selected book-tax differences. Furthermore, we assess whether proxies that are based upon earnings from two or three past years are more accurate than proxies that are based upon earnings from only one past year.

In a first analysis, we examine the accuracy of earnings-based proxies in identifying the availability of firm-level TLCFs. We use a panel of Italian listed firms between 2009 and 2012 (452 firm-year observations) and determine the true TLCF status for each firm-year observation. As Italy requires listed firms to prepare their unconsolidated financial statements in line with IFRS, we can hand-collect information on a firm’s true TLCF status from the notes on deferred tax assets provided in the unconsolidated IFRS statement. To obtain insights into the accuracy of earnings-based proxies, we compare the true TLCF status of our sample firms to the TLCF status predictions of the earnings-based proxies.

Our analysis shows that last year’s earnings before taxes perform quite well in predicting the availability of TLCFs on a firm-year basis. We find that the proxy correctly predicts whether a firm has TLCFs for 75.44% of all firm-year observations. Last year’s earnings before taxes are more accurate in identifying non-TLCF firms (80.73% correct predictions) than in identifying TLCF firms (64.90% correct predictions). This indicates that using this proxy to predict whether a firm has TLCFs might decrease the likelihood of identifying any differences in the behavior of TLCF and non-TLCF firms. At the same time, we do not expect an underestimation of the response of non-TLCF firms to tax phenomena. In line with this result, we find that there is an association between an incorrect prediction and the type of TLCF status prediction made. The use of last year’s earnings before taxes will thus lead to a measurement error in TLCF variables, which is not random. Our results further indicate that adjusting last year’s earnings before taxes for book-tax differences does not necessarily improve the proxy’s accuracy if it is not possible to precisely measure these differences. We find that the percentage of correct predictions decreases if last year’s earnings before taxes are adjusted for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption, whereas it increases if last year’s earnings before taxes are adjusted for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier. Moreover, our results suggest that the accuracy of earnings-based proxies changes only slightly if more past years are considered.

In a second analysis, we study the consequences of measurement error in TLCF variables which are used in regression models on capital structure choice. We rely upon the same panel of Italian listed firms and use the introduction of an allowance for corporate equity (ACE) in Italy in 2011 to examine how TLCFs affect the tax incentive to increase equity financing following the introduction of such a rule. We perform separate OLS regression analyses using either a firm’s true TLCF status or TLCF status predictions of earnings-based proxies and compare the coefficient estimates for the variable that quantifies the difference in the tax incentive for TLCF and non-TLCF firms. In line with prior research (Max et al. 2021; Plesko 2003), we expect that non-random measurement error biases the coefficient estimate for this variable downwards in magnitude.

If we use a firm’s true TLCF status, our results indicate that the relative increase in equity financing of a TLCF firm is about 36 percentage points lower than that of a non-TLCF firm. We also identify a lower increase in equity financing for TLCF firms if we use last year’s earnings before taxes as a proxy for a firm’s TLCF status. Measurement error lowers the magnitude of this effect, but the coefficient estimate is not statistically different from the coefficient estimate derived when relying upon a firm’s true TLCF status. We also do not find a significant difference in the effect of TLCFs on the increase in equity if we use last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier to identify whether a firm has TLCFs. Both last year’s earnings before taxes and last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense therefore serve as an accurate proxy for a firm’s TLCF status. Data restrictions, however, might not allow researchers to adjust last year’s earnings before taxes for nondeductible interest expense, whereas information on unadjusted last year’s earnings before taxes can be easily obtained from publicly available financial statement information. Since using last year’s earnings before taxes seems to lead to statistically and quantitatively similar conclusions as using a firm’s true TLCF status, we conclude that this proxy should be the preferred proxy in empirical studies that consider how TLCFs affect a firm’s capital structure choice.

Our results contribute to literature in several ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, the accuracy of earnings-based TLCF proxies has not been examined at the firm level so far. By comparing a firm’s true TLCF status to the TLCF status obtained when using earnings-based proxies, we inform researchers about the bias in descriptive statistics on the number of TLCF firms. Second, we are not aware of any study that assesses how the inaccuracy of earnings-based proxies in identifying whether a firm has TLCFs affects the results derived in regression models on capital structure choice. We close this gap by providing insights into the consequences of measurement error in TLCF variables in capital structure decisions. Third, our results inform policymakers that TLCFs serve as a substitute for corporate tax benefits not only with respect to debt financing, but also after the introduction of an ACE. Thus, the higher the number of firms with TLCFs, the more likely the tax incentives to build up additional equity will go unanswered.

2 Earnings-based TLCF proxies examined

In prior empirical capital structure research, last year’s earnings before taxes have often been used as a proxy for a firm’s TLCF status. Studies such as Bernasconi et al. (2005), Fossen and Simmler (2016), Haring et al. (2012), Krämer (2015), Overesch and Voeller (2010), Pfaffermayr et al. (2013) and Rünger et al. (2019) assume that a firm with negative last year’s earnings before taxes is also exposed to TLCFs. We therefore use last year’s earnings before taxes as the baseline proxy for a firm’s TLCF status in our analyses. To determine the TLCF status predictions of this proxy, we rely upon earnings information provided by the Amadeus database.Footnote 10 We assume that the proxy predicts the (non)availability of TLCFs in year t if the Amadeus data item Profit/Loss Before Taxation is (non)negative in year \(\it t-1\).

Last year’s earnings before taxes might not be accurate in identifying the availability of TLCFs as they do not account for any differences between tax and GAAP rules.Footnote 11 If listed firms have to prepare their unconsolidated financial statements in accordance with IFRS, as in Italy, differences between tax and IFRS rules can occur in many areas, such as the depreciation of tangible assets, the capitalization of intangible assets, the recognition of dividends and capital gains, the recognition of provisions or the deductibility of interest expense (Gavana et al. 2013; Giacometti 2009). However, with one exception, prior research that uses earnings-based TLCF proxies does not adjust earnings for book-tax differences. Oestreicher et al. (2012) consider that dividends received by a German firm are tax-free due to a participation exemption but must be fully recognized according to German GAAP. In their study, Oestreicher et al. (2012) therefore adjust earnings before taxes for tax-free dividends to determine existing amounts of TLCFs.

To see whether the accuracy of last year’s earnings before taxes in identifying the availability of TLCFs can be improved by adjusting earnings for book-tax differences, we construct two additional proxies. In particular, we consider two sources of book-tax differences, which frequently arise not only in Italy but also in most European countries: revenue that must be recognized according to IFRS but is tax-free due to a participation exemption and interest expense, which is deductible under IFRS but nondeductible for tax purposes due to an interest barrier.Footnote 12

The first proxy we examine accounts for the fact that dividends and capital gains received by an Italian firm are tax-exempt for 95% of the amount due to a participation exemption but must be fully recognized according to IFRS.Footnote 13 To calculate this proxy, we need information on a firm’s received dividends and capital gains. The Amadeus database does not provide separate data items for received dividends and capital gains. Received dividends and capital gains, however, are included—alongside interest revenue—in the Amadeus data item Financial Revenue. To determine our proxy, we deduct 95% of the amount reported in Financial Revenue from Profit/Loss Before Taxation in year \(\it t-1\) We assume that a firm has (no) TLCFs in year t if the respective outcome is (non)negative. As Financial Revenue also includes interest revenue, which is not covered by the participation exemption, our proxy cannot precisely measure the book-tax difference related to this exemption.Footnote 14 It is likely that the amount we deduct from last year’s earnings before taxes will be too large and hence, that our proxy will predict an income, which is too low compared to true taxable income. While this should not affect the proxy’s ability to correctly identify firms with TLCFs, it might reduce its ability to correctly identify firms without TLCFs.

The second proxy we examine accounts for the fact that interest deductions of a firm might be limited for tax purposes, whereas they are not for IFRS purposes. According to the Italian interest barrier, net interest expense, that is, interest expense minus interest revenue, is tax-deductible only up to an amount of 30% of a firm’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA), as determined for tax purposes.Footnote 15 To determine this proxy, we thus need information on a firm’s net interest expense and EBITDA. As the Amadeus database does not provide a data item for interest revenue, we assume that a firm’s net interest expense corresponds to its gross interest expense, as represented by the Amadeus data item Interest Paid. A firm’s EBITDA is represented by the Amadeus data item EBITDA. Using this information, we first determine a firm’s amount of nondeductible interest expense in year \(\it t-1\). We set the amount of nondeductible interest expense equal to zero and thus conclude that the Italian interest barrier does not apply if Interest Paid does not exceed 30% of the amount reported in EBITDA in year \(\it t-1\).Footnote 16 If Interest Paid exceeds 30% of the amount reported in EBITDA in year \(\it t-1\), we set the amount of nondeductible interest expense equal to the difference between Interest Paid and 30% of EBITDA. If EBITDA is negative in year \(\it t-1\), we set the amount of nondeductible interest expense equal to Interest Paid. In a second step, we determine our proxy’s TLCF status predictions by adding the amount of nondeductible interest expense to the data item Profit/Loss Before Taxation in year \(\it t-1\). We conclude that a firm has (no) TLCFs in year t if the respective outcome is (non)negative. As we assume that a firm’s net interest expense corresponds to its gross interest expense, our proxy cannot precisely measure the book-tax difference arising due to the interest barrier. It is likely that the amount we add to last year’s earnings before taxes will be too large and hence, that our proxy will predict an income, which is too high compared to true taxable income. This might reduce the proxy’s ability to correctly identify firms with TLCFs, while it should not affect its ability to correctly identify firms without TLCFs.Footnote 17

Tax losses can usually be carried forward for more than one year.Footnote 18 In Italy, tax losses incurred before 2011 could be carried forward for a total of five years. Tax losses incurred in 2011 or later can be carried forward indefinitely. Determining TLCF status predictions based upon last year’s earnings can negatively affect the accuracy of earnings-based proxies if losses realized in years further in the past are ignored. Furthermore, book-tax differences such as the depreciation of assets or the recognition of provisions might reverse over time. The sole focus on last year’s earnings could therefore further decrease the proxies’ accuracy. Several studies use earnings-based TLCF proxies that are based upon earnings from more than one year. Bernasconi et al. (2005), for example, proxy for the TLCF status of a firm by using earnings before taxes from the last two years. Buettner et al. (2009, 2011a, 2011b, 2012, 2016), Buettner and Wamser (2013), Egger et al. (2014), Overesch and Wamser (2010, 2014), and Wamser (2014) use information on GAAP loss-carryforwards, which also takes earnings from multiple years into account. To see whether proxies that are based upon earnings from more than one prior year are more accurate in identifying the availability of TLCFs, we also calculate our proxies based upon earnings from two and three prior years. To determine the TLCF status predictions of these proxies, we identify the first year over the period of two (three) years in which a firm’s earnings (unadjusted or adjusted earnings before taxes) are negative. We keep record of these negative earnings and add positive as well as negative earnings from all future periods until we reach year \(\it t-1\). If cumulated earnings in year \(\it t-1\) are (non)negative, we conclude that a firm has (no) TLCFs in year \(\it t\).Footnote 19

3 Sample

Our analyses are based upon a panel of Italian listed firms. Italy requires that listed firms publish not only their consolidated, but also their unconsolidated financial statements in accordance with IFRS. This allows us to determine a firm’s true TLCF status based upon IFRS statement information and thus to examine the accuracy of earnings-based TLCF proxies. As the use of IFRS for unconsolidated financial statements has been mandatory since 2006, and some of our proxies are based upon earnings from three past years, our observation period starts in 2009. For the end of our observation period, we choose 2012. Since Italy introduced an ACE rule in 2011, our observation period allows us to examine how the use of earnings-based TLCF proxies affects the coefficient estimates for variables that quantify the difference in the tax incentive for capital structure choice between TLCF firms and non-TLCF firms.

Except for information on a firm’s true TLCF status, which we hand-collect from IFRS statements, all information necessary for our analyses is obtained from the Amadeus database. As the Amadeus database does not provide any information on banks and insurance companies, we do not consider them for our analyses. Our preliminary sample size corresponds to 775 firm-year observations of Italian listed firms between 2009 and 2012. We exclude 111 firm-year observations for which the Amadeus database does not provide sufficient information to determine TLCF status predictions for all the proxies we examine. We also exclude 212 firm-year observations for which we cannot determine the firm’s true TLCF status, either because an unconsolidated IFRS statement is not publicly available or because the information provided in the IFRS statement is not sufficient to determine the true TLCF status. Our final sample covers 452 firm-year observations from 179 firms.

The size of the firms in our sample, as measured by total assets at the end of a given year, varies between 0.004 and 82.600 billion euros and corresponds to 2.370 billion euros, on average. The average sample firm is 34 years old, with firm age varying between 1 and 149 years. Almost half of the firms in our sample (49.32%) belong to the manufacturing industry, 49.75% are service providers. In total, 83.40% of all the firms in our sample have foreign subsidiaries.

4 Accuracy of earnings-based proxies in identifying the availability of TLCFs

4.1 Research design

In this section, we examine the accuracy of earnings-based proxies in identifying whether a firm has TLCFs. To do so, it is necessary to determine both the TLCF status as predicted by the earnings-based proxies and the true TLCF status of a firm.

To determine the TLCF status predictions of the earnings-based proxies, we follow the approach discussed in Sect. 2. To determine a firm’s true TLCF status, we rely upon information on TLCFs provided in a firm’s unconsolidated IFRS statement. In particular, we hand-collect information on deferred tax assets on TLCFs, which is provided in the notes to the unconsolidated IFRS statement. IAS 12.81 requires that a firm discloses the amount of deferred tax assets on TLCFs as well as the amount of TLCFs for which no deferred tax asset has been recorded. To determine the true TLCF status of a firm, we rely upon the following formula from Kager et al. (2011):

\({TLCF}_{t-1}\) corresponds to a firm’s amount of TLCFs at the end of year \(t-1\) and thus represents the amount available for deduction in year \(\it t\). \({DTA}_{t-1}\) represents the amount of deferred tax assets on TLCFs in year \(\it t-1\), and \({NDTA}_{t-1}\) represents the amount of TLCFs for which no deferred tax asset has been recorded.Footnote 20\({\tau }_{t-1}\) is the tax rate used by the firm to determine \({DTA}_{t-1}.\) The firms in our sample are subject to the Italian corporate income tax (IRES) and a regional tax on productive activities (IRAP). As only the Italian corporate income tax allows for tax losses to be carried forward, \({\tau }_{t-1}\) equals the Italian corporate income tax rate of year \(\it t-1\).Footnote 21 For our analyses, we assume that a firm has (no) TLCFs in year \(t\) if \({TLCF}_{t-1}\) is larger than (equal to) zero.Footnote 22 Out of the 452 firm-year observations in our sample, 296 do not have TLCFs (65.49%), whereas 156 have TLCFs (34.51%).

We perform two analyses to assess the accuracy of earnings-based proxies in identifying whether a firm has TLCFs. In our first analysis, we examine whether earnings-based proxies can correctly predict the TLCF status of firms on a firm-year basis. We compare the TLCF status predictions of our earnings-based proxies to the true TLCF status of each firm-year observation in our sample and determine the percentage of (in)correct TLCF status predictions for each proxy. In line with Niemann and Rechbauer (2013), we assume that the accuracy of an earnings-based proxy in identifying whether a firm has TLCFs increases (decreases) in the percentage of (in)correct predictions made. To assess whether earnings-based proxies perform differently in identifying firm-year observations with and without TLCFs, we also determine the percentage of (in)correct TLCF status predictions for the subsample of firm-year observations predicted to be non-TLCF firms and for the subsample of firm-year observations predicted to be TLCF firms. As the tax incentive in capital structure choice is lower for TLCF firms than for non-TLCF firms (DeAngelo and Masulis 1980), incorrectly classifying a TLCF firm as a non-TLCF firm could lead to an underestimation of the tax incentive for non-TLCF firms. The higher the percentage of TLCF firms incorrectly classified as non-TLCF firms, the harder it will be to identify a tax incentive for non-TLCF firms. This could lead to the incorrect conclusion that taxes do not matter in capital structure choice. If non-TLCF firms are incorrectly classified as TLCF firms, the likelihood of identifying any differences between TLCF and non-TLCF firms could decrease. However, it would still be possible to document a tax incentive for non-TLCF firms. Incorrectly classifying non-TLCF firms as TLCF firms is therefore less detrimental than incorrectly classifying TLCF firms as non-TLCF firms.

In our second analysis, we examine whether there is an association between an incorrect TLCF status prediction and the type of TLCF status prediction made. To this extent, we perform pairwise χ2-tests of independency. An association between an incorrect TLCF status prediction and the type of TLCF status prediction made indicates that the measurement error in TLCF variables will be non-random and that the coefficient estimates obtained for these variables will be biased downwards in magnitude (Max et al. 2021; Plesko 2003).

4.2 Results

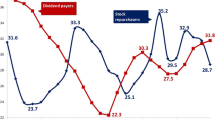

In Table 1, we provide insights into whether earnings-based proxies can correctly predict the TLCF status of a firm on a firm-year basis. We report the percentage of (in)correct TLCF status predictions made by each proxy for the whole sample of firm-year observations, the subsample of firm-year observations predicted to be non-TLCF firms and the subsample of firm-year observations predicted to be TLCF firms.

Panel A of Table 1 shows that it is possible to closely replicate the true distribution of non-TLCF and TLCF firms by using our baseline proxy, last year’s earnings before taxes. If we use last year’s earnings before taxes, we classify 301 of all firm-year observations as non-TLCF firms (66.59%) and 151 as TLCF firms (33.41%). The deviation from the true distribution of non-TLCF and TLCF firms, as shown in Sect. 4.1, amounts to only + /–1.10 percentage points. Our results also show that the proxy performs quite well in identifying whether a firm has TLCFs on a firm-year basis. The TLCF status predictions are correct for 75.44% of all firm-year observations if last year’s earnings before taxes are used. However, the fact that there are incorrect TLCF status predictions (24.56%) suggests that book-tax differences negatively affect the accuracy of last year’s earnings before taxes. Panel A of Table 1 further reveals that our baseline proxy performs better in identifying non-TLCF firms than TLCF firms. 80.73% of the predicted non-TLCF firms are true non-TLCF firms, while only 64.90% of the predicted TLCF firms are true TLCF firms. This indicates that using last year’s earnings before taxes might not lead to an underestimation of the tax incentive in capital structure choice for non-TLCF firms. It might, however, decrease the likelihood of identifying any differences in the tax incentive between TLCF and non-TLCF firms.

The pairwise χ2-test of independency shows that there is a significant association between an incorrect TLCF status prediction and the type of TLCF status prediction made. This suggests that the measurement error in TLCF variables, which are determined by relying upon last year’s earnings before taxes, is non-random. It will thus bias the coefficient estimates for these variables downwards in magnitude.

If we adjust last year’s earnings before taxes for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption, we observe a larger deviation from the true distribution of non-TLCF and TLCF firms than for our baseline proxy. By classifying 207 firm-year observations as non-TLCF firms (45.80%) and 245 firm-year observations as TLCF firms (54.20%), this proxy overestimates (underestimates) the true percentage of (non-)TLCF firms by as much as 19.69 percentage points. Furthermore, as shown in Panel B of Table 1, the overall percentage of correct TLCF status predictions decreases from 75.44% to 69.69% (–5.75 percentage points). This suggests than an adjustment for the book-tax difference related to a participation exemption does not improve the accuracy of last year’s earnings before taxes if it is not possible to precisely measure the effects of the participation exemption. As pointed out in Sect. 2, it is likely that our proxy will predict an income, which is too low compared to true taxable income. This will likely reduce its ability to correctly identify firms without TLCFs and hence, firms with no TLCFs will be incorrectly classified as TLCF firms. The results derived for our subsamples support this assumption. The percentage of correct predictions decreases by 11.02 percentage points if a firm is predicted to be a TLCF firm (from 64.90% to 53.88%). In contrast, the percentage of correct predictions increases by 7.68 percentage points if a firm is predicted to be a non-TLCF firm (from 80.73% to 88.41%). As last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for a participation exemption perform better in identifying non-TLCF firms than in identifying TLCF firms, using this proxy might not lead to an underestimation of the tax incentive in capital structure choice for non-TLCF firms. However, it is very likely that this proxy cannot identify any differences in the tax incentive between TLCF and non-TLCF firms.

The pairwise χ2-test of independency shown in Panel B of Table 1 indicates that there is a significant association between an incorrect TLCF status prediction and the type of TLCF status prediction made. The measurement error in TLCF variables will thus be non-random if an adjustment for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption is made and we therefore expect a downward bias in the magnitude of the coefficient estimates for these variables.

If we adjust last year’s earnings before taxes for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier, 335 firm-year observations are classified as non-TLCF firms (74.12%) and 117 firm-year observations are classified as TLCF firms (25.88%). This proxy thus underestimates (overestimates) the true percentage of (non-)TLCF firms in our sample by 8.63 percentage points. Although this proxy is less accurate in predicting the true distribution of non-TLCF and TLCF firms, it is slightly more accurate in identifying whether a firm has TLCFs on a firm-year basis than our baseline proxy. Although we can also not precisely measure the book-tax difference arising due to an interest barrier, the percentage of correct TLCF status predictions increases from 75.44% to 77.21% (+ 1.77 percentage points). A closer examination of the results provided for the subsamples in Panel C of Table 1 reveals that an adjustment for nondeductible interest expense increases the percentage of correct predictions from 64.90% to 72.65% if the availability of TLCFs is predicted (+ 7.75 percentage points), while it slightly decreases the percentage of correct predictions from 80.73% to 78.81% if the nonavailability of TLCFs is predicted (–1.92 percentage points). The latter finding is likely related to our imprecise measurement of the effects of the interest barrier. As pointed out in Sect. 2, our proxy will predict an income which is too high compared to true taxable income. It is thus likely that the proxy’s ability to correctly identify firms with TLCFs will be reduced and hence, that firms with TLCFs will be incorrectly classified as non-TLCF firms. Since last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for an interest barrier outperform our baseline proxy in identifying firms with TLCFs, it will be more likely that this proxy can identify any differences in the tax incentive in capital structure choice between TLCF and non-TLCF firms. At the same time, since the proxy performs similar to our baseline proxy in identifying firms without TLCFs, we expect that using last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for an interest barrier will also not lead to an underestimation of the tax incentive for non-TLCF firms.

The pairwise χ2-test of independency does not suggest a significant association between an incorrect TLCF status prediction and the type of TLCF status prediction made. Coefficient estimates for TLCF variables, which are based on last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense, should therefore not be affected by measurement error.Footnote 23

The accuracy of earnings-based proxies changes only slightly if we base the TLCF status predictions upon earnings from two or three past years instead of only one past year. For our baseline proxy, unadjusted earnings before taxes, the percentage of correct predictions increases by 0.89 (2.21) percentage points if earnings from two (three) past years are used to determine the proxy’s TLCF status predictions instead of only last year’s earnings. This pattern can be observed for both, the subsample of non-TLCF firms and the subsample of TLCF firms. The results for non-TLCF firms suggest that the accuracy of our baseline proxy increases if TLCF status predictions are based upon a higher number of years, because book-tax differences might reverse over time. The results for TLCF firms indicate that determining TLCF status predictions based upon a higher number of years leads to a better identification of losses that have been realized further in the past.

While earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier also perform slightly better in identifying the TLCF status of firms if earnings from two or three past years are used instead of only last year’s earnings,Footnote 24 the opposite is true for earnings before taxes adjusted for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption. For the latter proxy, the percentage of correct predictions decreases by 0.66 (1.11) percentage points if earnings from two (three) past years are used instead of only last year’s earnings. It is likely that this result can be attributed to our imprecise measurement of the book-tax difference related to the participation exemption. If our proxy predicts an income, which is too low compared to true taxable income in every single year, the ability of our proxy to correctly identify non-TLCF firms will decrease in the number of past years considered. As a consequence, a higher number of non-TLCF firms will be incorrectly classified as TLCF firms. Our subsample analyses support this assumption. For firm-year observations predicted to be TLCF firms, the percentage of correct predictions decrease by 0.80 (1.27) percentage points if TLCF status predictions are based upon earnings from two (three) past years instead of only last year’s earnings. There is no such pattern for firm-year observations predicted to be non-TLCF firms.

Overall, our results show that earnings-based proxies perform quite well in identifying whether a firm has TLCFs on a firm-year basis. The most accurate of the proxies we examine is earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier. However, adjusting for book-tax differences does not always improve the predictive power of earnings-based proxies. If—due to data restrictions—it is not possible to precisely measure these differences, such adjustments might even worsen the ability of proxies to correctly identify whether a firm has TLCFs. Another important finding is that earnings-based proxies, in general, perform better in identifying non-TLCF firms than in identifying TLCF firms. We therefore do not expect an underestimation of the tax incentive in capital structure choice for non-TLCF firms if one of our proxies is used. However, there might be a decrease in the likelihood of identifying any differences in the tax incentive between TLCF and non-TLCF firms. For most proxies, our results reveal a significant association between an incorrect prediction and the type of TLCF status prediction made. The measurement error in TLCF variables, which are based upon these proxies, will therefore not be random and will bias the coefficient estimates derived for these variables downwards in magnitude.Footnote 25 Detailed insights into the consequences with respect to measurement error in TLCF variables in regression models on capital structure choice are provided in Sect. 5.

5 Earnings-based proxies and measurement error in regression models on capital structure choice

5.1 Research design

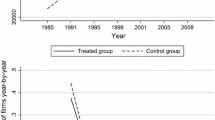

As shown in Sect. 4.2, there will be measurement error in TLCF variables used in regression models if earnings-based proxies are used to identify whether a firm has TLCFs. In this section, we investigate the effect of such a measurement error on coefficient estimates that quantify the difference in tax incentives for TLCF and non-TLCF firms in capital structure choice. To do so, we use the introduction of an ACE in Italy in 2011,Footnote 26 and examine whether TLCFs affect a firm’s tax incentive to increase equity financing.

First, we obtain a benchmark coefficient estimate, which represents the true impact of TLCFs on the tax incentive to increase equity financing following the introduction of the Italian ACE. We estimate the following OLS regression model and use the true TLCF status of a firm for our TLCF variable:Footnote 27

\({\Delta EQT}_{i,t}\) corresponds to the change in equity of firm \(\it i\) from year \(\it t-1\) to year \(t\) relative to the stock of equity at the end of year \(\it t-1\) (Petutschnig and Rünger 2022). \({TLCF}_{i,t}\) is a dummy variable, which is equal to one if firm \(\it i\) has TLCFs in year \(\it t\) and zero otherwise. It captures how equity financing differs between firms with and without TLCFs in the years prior to the introduction of the Italian ACE (2009 and 2010) and therefore represents the impact of TLCFs on changes in equity absent any tax incentives. As pointed out above, we rely upon a firm’s true TLCF status to determine \({TLCF}_{i,t}\) in this baseline regression. \({ACE}_{t}\) is a dummy variable, which is equal to one in years in which the Italian ACE was in place (2011 and 2012) and zero in years in which it was not. It captures how equity financing of non-TLCF firms changed after the introduction of the Italian ACE relative to the years prior to the introduction. Prior literature shows that an ACE increases the tax incentive of firms to use equity financing since it offers a tax benefit in the form of a notional interest deduction on equity (Bernasconi et al. 2005; Branzoli and Caiumi 2020; Hebous and Ruf 2017; Klemm 2007; Panier et al. 2015; Panteghini et al. 2012; Petutschnig and Rünger 2022; Princen 2012; Schepens 2016; Van Campenhout and Van Caneghem 2013). We thus expect a positive sign for the coefficient for \({ACE}_{t}\). As \({ACE}_{t}\), however, captures a mere time trend, we cannot rule out that the coefficient for \({ACE}_{t}\) will also be affected by macroeconomic changes.Footnote 28 The interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) is our main variable of interest. It captures how TLCFs affect the tax incentive to increase equity financing following the introduction of the Italian ACE. We expect that the tax incentive to increase equity financing is lower for a firm with TLCFs, an assumption which is in line with the substitution hypothesis (DeAngelo and Masulis 1980). Due to being at least partially tax-exempt, a firm with TLCFs cannot immediately benefit from a notional interest deduction on equity. The coefficient for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) should therefore have a negative sign.

\({X}_{i,t}\) represents a vector of control variables and follows prior literature on capital structure choice (De Simone and Lester 2018; Faulkender and Smith 2016; Heitzman and Lester 2021b; Huizinga et al. 2008; Klemm 2007; Panteghini et al. 2012; Pfaffermayr et al. 2013; Petutschnig and Rünger 2022; Schulman et al. 1996). It includes controls for a firm’s profitability, revenue, size, age and foreign activity as well as industry fixed effects.Footnote 29

Second, we re-estimate Eq. 2 using the TLCF status predictions of our earnings-based proxies rather than a firm’s true TLCF status for the TLCF variable.Footnote 30 To gain insights into the extent to which measurement error affects the coefficient estimates that quantify the difference in the tax incentive in capital structure choice for TLCF and non-TLCF firms, we compare the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) when using an earnings-based TLCF proxy to our benchmark coefficient estimate.Footnote 31 In line with prior literature (Max et al. 2021; Plesko 2003), we expect that a non-random measurement error will lead to an attenuation effect, i.e., the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) will be biased downwards in magnitude if an earnings-based proxy is used.Footnote 32 To statistically evaluate the impact of measurement error, we perform Wald tests.

5.2 Results

In Table 2, we show OLS regression results for the benchmark regression, in which we use a firm’s true TLCF status to examine how the availability of TLCFs affects the tax incentive to increase equity financing following the introduction of an ACE.

As expected, we find that non-TLCF firms increase equity financing following the introduction of an ACE. The coefficient for the dummy variable \({ACE}_{t}\) is positive. However, it is very small in size and not statistically different from zero. This result does not necessarily imply that the Italian ACE was not effective in incentivizing firms to increase equity financing. First, we cannot rule out that the results derived for \({ACE}_{t}\) are affected by other macroeconomic changes. Hence, an increase in equity financing due to the introduction of the Italian ACE could have been reduced by a decrease in equity financing due to other macroeconomic changes in the years after the reform (e.g., the aftermath of the financial crisis). Second, the small size of our sample might make it harder to identify any significant results.

In line with our assumption that the tax incentive to increase equity financing following the introduction of an ACE is smaller for a firm with TLCFs, we find that the coefficient for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) is negative and statistically significant at the 5% level. Column 4 of Table 2 shows that the impact of TLCFs is substantial. For a firm with TLCFs, the relative increase in equity financing following the introduction of an ACE is about 36 percentage points smaller than for a firm without TLCFs. This finding is robust across the different specifications of our regression model shown in Table 2. Among our control variables, we find that profitability (\({PROFIT}_{i,t}\), only in some specifications) as well as size (\({SIZE}_{i,t}\)) have a significant positive effect and that sales (\({SALES}_{i,t}\)) has a significant negative effect on the change in equity.

In Table 3 we present the OLS regression results obtained when we use earnings-based TLCF proxies for our TLCF variable. Table 3 thus provides insights into the extent to which the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) differs from the benchmark coefficient estimate of –0.363 if an earnings-based TLCF proxy is used.

Column 1 of Panel A of Table 3 shows that the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) is negative and significant if we use last year’s earnings before taxes to determine whether a firm has TLCFs. Thus, we can still identify a difference between TLCF firms and non-TLCF firms in the tax incentive to increase equity financing. The magnitude of the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\), however, changes from − 0.363 to − 0.326. This corresponds to a downward bias in absolute size of about 3.7 percentage points. The Wald test reveals that the difference between the two coefficient estimates is not statistically significant. This indicates that although there is a non-random measurement error in the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) if last year’s earnings before taxes are used to predict the availability of TLCFs, the impact of the measurement error is negligible.Footnote 33

If we adjust last year’s earnings before taxes for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption (Column 1 of Panel B of Table 3), we can also still observe a significant difference between TLCF and non-TLCF firms in the tax incentive to increase equity financing. The magnitude of the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\), however, corresponds to − 0.185 and is therefore only about half as large as our benchmark coefficient estimate of − 0.363. In contrast to our baseline proxy, the difference between the two coefficient estimates is statistically significant at the 5% level. The use of last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption will thus result in a significant underestimation of the impact of TLCFs on a firm’s tax incentive to increase equity financing following the introduction of an ACE.

If we use last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier (Column 1 of Panel C of Table 3), the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) amounts to − 0.401 and is statistically significant. As for the other proxies, we can still identify a difference between TLCF firms and non-TLCF firms in the tax incentive to increase equity financing. The Wald test confirms that the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) is not significantly different from our benchmark coefficient estimate of − 0.363. This is line with the findings obtained in Sect. 4.2, which do not indicate the existence of an attenuation effect for this proxy.Footnote 34

Our conclusions regarding the effect of a measurement error in the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) mostly hold if we increase the number of past years considered to calculate our TLCF status predictions. We therefore conclude that increasing the number of past years considered to calculate the TLCF status predictions of earnings-based proxies does not change the effects of measurement error.

The coefficients for the control variables included in the regression analysis do not fundamentally change if an earnings-based proxy and not a firm’s true TLCF status is used to determine our TLCF variable.

Overall, our results suggest that the difference in the tax incentive in capital structure choice of TLCF firms and non-TLCF firms can still be identified if earnings-based proxies are used to predict whether a firm has TLCFs. Non-random measurement error in TLCF variables, however, can bias coefficient estimates that quantify the difference in the tax incentives in capital structure choice for TLCF and non-TLCF firms downwards in magnitude. The coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\), which is based upon last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier, does not differ significantly from the coefficient estimate based upon a firm’s true TLCF status. This proxy therefore serves as an accurate proxy in empirical studies that consider how TLCFs affect a firm’s capital structure choice. We acknowledge, however, that data restrictions might not allow researchers to calculate this proxy. Our results also show that the use of last year’s earnings before taxes leads to statistically and quantitatively similar conclusions as those obtained when relying upon a firm’s true TLCF status. At the same time, information on unadjusted earnings before taxes can be easily accessed via publicly available financial statement information. We therefore conclude that it would also be recommendable to rely upon unadjusted earnings before taxes to identify whether a firm has TLCFs.

6 Conclusion

Many empirical tax studies, including those on capital structure choice, control for a firm’s TLCF status. If a firm’s true TLCF status cannot be assessed from publicly available financial statement information, researchers often use earnings-based information to proxy for the TLCF status of a firm. In this paper, we identify the most commonly used earnings-based TLCF proxies in empirical capital structure research and study their accuracy.

First, we examine the accuracy of earnings-based TLCF proxies in identifying the availability of firm-level TLCFs. To this extent, we determine a firm’s true TLCF status based upon information on deferred tax assets on TLCFs provided in the firm’s unconsolidated IFRS statement. Next, we predict the TLCF status of the same firm using various earnings-based TLCF proxies. Our baseline proxy, which has been predominantly used in prior research, is last year’s earnings before taxes. Alternatively, we adjust this baseline proxy for selected book-tax differences, in particular tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption or nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier. Furthermore, we also follow a multiperiod approach and calculate our earnings-based proxies based upon earnings from two or three past years. We evaluate the accuracy of earnings-based proxies on a firm-year basis by comparing the proxies’ TLCF status predictions to the true TLCF status of a firm.

Our sample consists of 452 firm-year observations from 179 Italian listed firms over the years 2009–2012, for which we are able to determine the true TLCF status. We find that last year’s earnings before taxes perform quite well in predicting the availability of TLCFs. In 75.44% of all cases, the predicted TLCF status corresponds to the firm’s true TLCF status. Furthermore, the proxy tends to perform better in identifying non-TLCF firms (80.73% correct predictions) than in identifying TLCF firms (64.90% correct predictions). Based on this result, we do not expect an underestimation of the tax incentive in capital structure choice for non-TLCF firms if this proxy is used to predict whether a firm has TLCFs. However, there might be a decrease in the likelihood of identifying any differences in the tax incentive between TLCF firms and non-TLCF firms. We also identify a non-random measurement error in TLCF variables that are based upon last year’s earnings before taxes.

Our results further indicate that an adjustment for book-tax differences can improve the accuracy of last year’s earnings before taxes even if it is not possible to precisely measure these book-tax differences. Specifically, we find that adjusting last year’s earnings before taxes for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier slightly increases the percentage of correct predictions (77.21%), but more importantly our results do not indicate the existence of an attenuation effect for this proxy. In contrast, adjusting last year’s earnings before taxes for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption does not improve the proxy’s accuracy. Furthermore, our results suggest that the accuracy of earnings-based proxies does not necessarily improve if more past years are considered.

Second, we evaluate the consequences of measurement error in TLCF variables used in regression models on capital structure choice. Based on the same panel of Italian listed firms, we study the effect of the introduction of the Italian ACE in 2011 on the increase in equity financing for firms with and without TLCFs. Our baseline regression analysis, which considers a firm’s true TLCF status, reveals that the relative increase in equity financing after the introduction of the ACE is significantly lower (about 36 percentage points) for firms with TLCFs than for firms without, a finding which is in line with the substitution hypothesis. Although we can still identify a negative effect of TLCFs if we use last year’s earnings before taxes as a proxy for a firm’s TLCF status, measurement error in the TLCF variable lowers this effect. However, if we compare the true effect of TLCFs to the effect obtained when using last year’s earnings before taxes, the difference between both is not statistically significant. There is also no significant difference in the effect of TLCFs on the increase in equity financing if we use last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier to identify whether a firm has TLCFs. Both last year’s earnings before taxes and last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense therefore serve as an accurate proxy for a firm’s TLCF status. Since information on last year’s earnings before taxes can be easily obtained, whereas data restrictions might not allow researchers to adjust for nondeductible interest expense, we conclude that last year’s earnings before taxes should be the preferred proxy in empirical tax research. It leads to statistically and quantitatively similar conclusions on the effect of TLCFs on a firm’s capital structure choice as a firm’s true TLCF status.

Notes

Prior research shows that firms have accumulated substantial amounts of TLCFs in past years. Kager and Niemann (2013), for example, find that from 2004 until 2008, average TLCFs of Austrian, German and Dutch listed groups varied between 70 and 152 million euros. TLCF stocks were, on average, 3.65 to 10.86 times as high as a group’s level of revenue. Heitzman and Lester (2021a) report that average TLCFs of large US groups were equal to 823.40 million US dollars between 2010 and 2015. Dwenger and Steiner (2012) show that average TLCFs of German firms increased from 1.24 million euros in 1998 to 2.12 million euros in 2004. Hopland et al. (2017) point out that between 1998 and 2005, TLCFs of Norwegian firms reached levels as high as 256.36% of taxable income. These results indicate that firms with TLCFs might be in a state of tax exemption over several years.

For an overview, see Max et al. (2021).

Related to the substitution hypothesis, Feld et al. (2012), in a meta-analysis, provide evidence that marginal tax effects on debt are more pronounced if loss-making firms, that is firms with losses in the current year, are excluded from the sample.

Heitzman and Lester (2021a) focus on the development of a measure, which captures the tax benefits of US firms’ TLCF amounts, i.e., reductions in future tax payments, more precisely than Compustat’s data item #52. The measure developed takes federal, state and foreign TLCFs into account and has recently been applied by Heitzman and Lester (2021b).

Similar, Heitzman and Lester (2021a) attribute a large part of the discrepancy between their measure of TLCF benefits and Compustat data to foreign TLCFs realized by multinational firms in their sample.

An exception are groups that apply a group taxation regime.

All Amadeus data items that we use are obtained from Bureau van Dijk’s Global Standard Format. Therefore, our proxies can also be replicated by using any other database from Bureau van Dijk.

This problem might be especially pronounced in countries with low book-tax conformity. The book-tax conformity of European countries has been evaluated by Watrin et al. (2014).

As mentioned before, there exist many other book-tax differences. We are, however, not able to consider additional book-tax differences since detailed information on the depreciation of assets, the nature of intangible assets or provisions is not available in the Amadeus database.

Besides Italy, most other European countries also apply a participation exemption, which (partially) exempts dividends and/or capital gains. In some countries, dividends and/or capital gains are only tax-exempt if certain minimum participation thresholds are met. Also, some countries do not fully exempt dividends and/or capital gains, but tax them at a reduced corporate tax rate. Further details can be found in Alvarado et al. (2021).

As the Amadeus database does not provide a data item for interest revenue, it is not possible to re-add interest revenue to our proxy.

The Italian interest barrier is very similar to the interest barrier of the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD), which all EU member states had to implement by 2019. Similarly to Italy, several other member states had already introduced an interest barrier before 2019, i.e., Bulgaria, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Spain. Further insights can be found in Petutschnig et al. (2019).

We also assume that the amount of nondeductible interest expense is equal to zero in years in which the Italian interest barrier was not in effect (years prior to 2007).

The precision of our proxy in accounting for the book-difference related to the Italian interest barrier might be affected by further data restrictions. First, as EBITDA for tax purposes is not available in the Amadeus database, we rely upon EBITDA for IFRS purposes to determine the amount of nondeductible interest expense. Second, if Italian firms opt for a group taxation regime, the amount of nondeductible interest expense must be determined at the level of the group and not at the level of the single firm. Based upon information provided by the Amadeus database, it is, however, not possible to determine the amount of nondeductible interest expense at the level of the group. We therefore determine the amount of nondeductible interest expense at the level of the single firm. It is unclear whether these limitations will cause our proxy to over- or underestimate true taxable income.

An overview of TLCF rules in different countries has been provided by Bethmann et al. (2018).

An algebraic presentation of how we determine the TLCF status predictions of the earnings-based proxies examined is shown in the Appendix.

A deferred tax asset for TLCFs is recorded to the extent that a firm deems it probable to realize future income against which the TLCFs can be offset. There are two reasons that can explain why a firm does not record a deferred tax asset for an existing TLCF. First, a firm might not expect to realize positive taxable income over the next years against which its TLCFs can be offset. Second, for periods before 2011, TLCFs realized by Italian firms could be carried forward for five years only. Hence, a firm will not record a deferred tax asset for TLCFs, which expire in the current year. In the former case, a firm can still be classified as a TLCF firm as it will be tax-exempt in the next year. In the latter case, a firm could be classified as a TLCF firm although it will have to pay taxes in the next year. To see whether the inclusion of firms in our sample that only report TLCFs, for which no deferred tax assets have been recorded, affects the results derived regarding the accuracy of earnings-based proxies, we perform a robustness test, in which we exclude those firms (55 firm-year observations in total). The results obtained regarding the accuracy of earnings-based proxies do not change qualitatively if we exclude firms that only report TLCFs, for which no deferred tax assets have been recorded.

The Italian corporate income tax rate is a flat tax, which amounted to 27.5% during our observation period.

There are some empirical studies that indicate an imprecise reporting behavior of firms regarding IAS 12.81. Kager and Niemann (2013), for example, show that Austrian, German and Dutch firms sometimes do not publish the amount of TLCFs for which no deferred tax asset has been recorded (that is, \({NDTA}_{t-1}\) in Formula 1) in their financial statement. Similar evidence is provided by Petermann and Schanz (2013). As we determine only whether a firm is exposed to TLCFs and not the exact amount of the TLCFs, an imprecise reporting behavior regarding IAS 12.81 should not substantially affect the quality of our true TLCF status measure.

Our results show that last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption leads to an increase in the percentage of correct predictions for non-TLCF firms compared to our baseline proxy. In contrast, using last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier increases the percentage of correct predictions for TLCF firms compared to our baseline proxy. To test whether a proxy that considers both sources of book-tax differences would increase correct predictions for both TLCF and non-TLCF firms, we adjust earnings before taxes by both tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption and nondeductible interest expense due to an interest barrier. The results derived regarding the proxy’s accuracy are, however, similar to the results derived for the proxy that only accounts for the effects of a participation exemption. Considering both sources of book-tax differences does not increase correct predictions for both TLCF and non-TLCF firms as the effect of the imprecise measurement of tax-free revenue due to a participation exemption outweighs the benefits of taking nondeductible interest expense into account.

The Italian interest barrier allows firms to carry forward nondeductible interest expense to future years. If the interest barrier does not apply in future years because net interest expense does not exceed 30% of a firm’s EBITDA, an interest carryforward from previous years can be deducted as an additional expense to the extent that it does not exceed the difference between net interest expense and 30% of EBITDA. In a non-tabulated robustness test, we also consider the possibility of an interest carryforward when determining the TLCF status predictions of the proxy that accounts for the book-tax difference related to the interest barrier. The results show that considering this additional feature of an interest barrier does not further improve the proxy’s accuracy in identifying whether a firm has TLCFs but rather complicates the way the proxy’s TLCF status predictions are determined.

Italian firms might opt for a group taxation regime where profits as well as losses of related companies are pooled and taxed at the level of the parent company. In a tax group, TLCFs thus arise only at the level of the parent company. As we determine the TLCF status predictions of our earnings-based proxies at the level of the single firm, our proxies might be inaccurate for firms that apply the Italian group taxation regime. In a non-tabulated robustness test, we exclude firms that opt for a group taxation regime from our sample. We exploit information on group taxation published in a firm’s IFRS statement to determine whether a firm opts for the Italian group taxation regime. Results on the percentage of (in)correct TLCF status predictions as well as on the level of association between an incorrect TLCF status prediction and the type of TLCF status prediction made do not qualitatively change if we exclude firms that are part of a tax group from our sample.

The Italian ACE was introduced to incentivize firms to increase equity. It allows firms to deduct notional interest on equity for tax purposes. The basis for this notional interest deduction is the increase in equity over the stock of equity available at the end of 2010. The applicable interest rate corresponds to the average return on Italian public debt securities with risk adjustments made (Branzoli and Caiumi 2020; Leone and Zanotti 2012).

We determine a firm’s true TLCF status as described in Sect. 4.1.

To disentangle the effect of the ACE from a mere time trend, we would have to add a control group that consists of firms from another country to our sample. A policy evaluation, however, is not the focus of this study. We are primarily interested in the difference in the tax incentive in capital structure choice for TLCF and non-TLCF firms. Furthermore, we could only use a country that requires firms to prepare their unconsolidated financial statements in line with IFRS during our observation period (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece, Lithuania, Malta) as a control group. None of these countries is reasonably similar to Italy from a macroeconomic perspective and could therefore be considered as a suitable control group.

For a detailed description of how we define the control variables, see Table 2.

We determine the TLCF status predictions of the earnings-based proxies as described in Sect. 2.

Branzoli and Caiumi (2020) also analyze the impact of the Italian ACE on the financing behavior of Italian manufacturing firms, but do not separately control for firms with TLCFs. An alternative research design, which has also been applied by Max et al. (2021) in a TLCF-context, would be to replicate the results of Branzoli and Caiumi (2020) and additionally control for the TLCF status of firms. This would allow us to analyze the effect of firms with TLCFs as well as how the results change if the TLCF status as identified by our earnings-based proxies is added to the regression model. Unfortunately, we cannot follow this path for two reasons: First, Branzoli and Caiumi (2020) use confidential corporate tax return data in their analysis, which we cannot assess. Second, we can only determine the true TLCF status of Italian listed firms, since we need information from unconsolidated IFRS statements. Branzoli and Caiumi (2020) analyze a total of 81,534 firms, the vast majority of them being nonlisted firms.

It is also possible that there are omitted variables that affect both our dependent variable (\({\Delta EQT}_{i,t}\)) and our TLCF variable. If earnings-based proxies are less affected by those omitted variables than a firm’s true TLCF status, the coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) would be biased upwards in magnitude if earnings-based proxies are used to determine whether a firm has TLCFs. As a result, the omitted variable bias could compensate (part of) the attenuation effect.

We cannot rule out, however, that an omitted variable bias (see Footnote 32) compensates part of the effect of the measurement error on the coefficient estimate derived for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\).

The coefficient estimate for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\) is larger in magnitude if we use last year’s earnings before taxes adjusted for nondeductible interest expense rather than a firm’s true TLCF status. This suggests an upward bias in magnitude due to omitted variables, which, however, does not result in a statistically significant difference between the coefficient estimates derived for the interaction term \({TLCF}_{i,t}\times {ACE}_{t}\).

References

Alvarado M, Cotrut M, De Lillo F, Gerzova L, Krajcuska F, Olejnicka M, Perdelwitz A, Rodriguez B, Schellekens M, Vlasceanu R (2021) European Tax Handbook 2021. IBFD

Bernasconi M, Marenzi A, Pagani L (2005) Corporate financing decisions and non-debt tax shields: evidence from Italian experiences in the 1990s. Int Tax Public Finance 12:741–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-005-2914-1

Bethmann I, Jacob M, Müller MA (2018) Tax loss carrybacks: Investment stimulus versus misallocation. Account Rev 93:101–125. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51956

Blouin J, Core JE, Guay W (2010) Have the tax benefits of debt been overestimated? J Financ Econ 98:195–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.04.005

Branzoli N, Caiumi A (2020) How effective is an incremental ACE in addressing the debt bias? Evidence from corporate tax returns. Int Tax Public Finance 27:1485–1519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-020-09609-2

Buettner T, Wamser G (2013) Internal debt and multinational profit shifting: Empirical evidence from firm-level panel data. Natl Tax J 66:63–95. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2013.1.03

Buettner T, Overesch M, Schreiber U, Wamser G (2009) Taxation and capital structure choice: evidence from a panel of German multinationals. Econ Lett 105:309–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2009.09.001

Buettner T, Overesch M, Schreiber U, Wamser G (2011a) Corporation taxes and the debt policy of multinational firms: Evidence for German multinationals. J Bus Econ 81:1325–1339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-011-0520-5

Buettner T, Overesch M, Wamser G (2011b) Tax status and tax response heterogeneity of multinationals’ debt finance. Public Finance Analysis 67:103–122. https://doi.org/10.1628/001522111X588781

Buettner T, Overesch M, Schreiber U, Wamser G (2012) The impact of thin-capitalization rules on the capital structure of multinational firms. J Public Econ 96:930–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.06.008

Buettner T, Overesch M, Wamser G (2016) Restricted interest deductibility and multinationals’ use of internal debt finance. Int Tax Public Finance 23:785–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-015-9386-8

Collins JH, Shackelford DA (1992) Foreign tax credit limitations and preferred stock issuances. J Account Res 30:103–124

DeAngelo H, Masulis RW (1980) Optimal capital structure under corporate and personal taxation. J Financ Econ 8:3–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(80)90019-7

De Simone L, Lester R (2018) The effect of foreign cash holding on internal capital markets and firm financing. In: SSRN working paper

Devereux MP, Maffini G, Xing J (2018) Corporate tax incentives and capital structure: new evidence from UK firm-level tax returns. J Bank Finance 88:250–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.12.004

Dhaliwal DS, Newberry KJ, Weaver CD (2005) Corporate taxes and financing methods for taxable acquisitions. Contemp Account Res 22:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1506/n4cq-jr8f-xluc-m50w

Dwenger N, Steiner V (2012) Profit taxation and the elasticity of the corporate income tax base: evidence from German corporate tax return data. Natl Tax J 65:117–150. https://doi.org/10.1086/NTJ41791115

Dwenger N, Steiner V (2014) Financial leverage and corporate taxation: evidence from German corporate tax return data. Int Tax Public Financ 21:1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9259-3

Egger P, Keuschnigg C, Merlo V, Wamser G (2014) Corporate taxes and internal borrowing within multinational firms. Am Econ J Econ Pol 6:54–93. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.6.2.54

Faulkender M, Smith JM (2016) Taxes and leverage at multinational corporations. J Financ Econ 122:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2016.05.011

Feld LP, Heckemeyer JH, Overesch M (2012) Capital structure choice and company taxation: a meta-study. J Bank Finance 37:2850–2866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.03.017

Fossen FM, Simmler M (2016) Personal taxation of capital income and the financial leverage of firms. Int Tax Public Finance 23:48–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-015-9349-0

Froot K, Hines JR (1995) Interest allocation rules, financing patterns, and the operations of US multinationals. In: Feldstein M, Hines J, Hubbard G (eds) The effects of taxation on multinational corporations. University of Chicago Press, pp 277–307

Gavana G, Guggiola G, Marenzi A (2013) Evolving connections between tax and financial reporting in Italy. Account Europe 10:43–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2013.774733

Giacometti P (2009) Italy implements provisions for the tax treatment of IFRS adopters. Int Tax Rev 20:59

Givoly D, Hayn C, Ofer AR, Sarig O (1992) Taxes and capital structure: evidence from firms’ response to the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Rev Financ Stud 5:331–355. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/5.2.331

Graham JR (1996) Debt and the marginal tax rate. J Financ Econ 41:41–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(95)00857-B

Graham JR (2000) How big are the tax benefits of debt? J Finance 55:1901–1941. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00277

Graham JR, Lemmon ML, Schallheim JS (1998) Debt, leases, taxes, and the endogeneity of corporate tax status. J Finance 53:131–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.55404

Hanlon M, Heitzman S (2010) A review of tax research. J Account Econ 50:127–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.09.002

Haring M, Niemann R, Rünger S (2012) Corporate financial policy and individual income taxation in Austria. Bus Admin Rev 74:473–486

Hebous S, Ruf M (2017) Evaluating the effects of ACE systems on multinational debt financing and investment. J Public Econ 156:131–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.02.011

Heitzman S, Lester R (2021a) Tax loss measurement. Natl Tax J 74:867–893. https://doi.org/10.1086/716849

Heitzman S, Lester R (2021b) Net operating loss carryforwards and corporate savings policies. Account Rev. https://doi.org/10.2308/TAR-2019-0085

Hopland AO, Lisowsky P, Mardan M, Schindler D (2017) Flexibility in income shifting under losses. Account Rev 93:163–183. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51907

Huizinga H, Laeven L, Nicodeme G (2008) Capital structure and international debt shifting. J Financ Econ 88:80–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.05.006

Kager R, Niemann R (2013) Income determination for corporate tax purposes using IFRS as a starting point: Evidence for listed companies within Austria, Germany and the Netherlands. J Bus Econ 83:437–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-013-0661-9

Kager R, Niemann R, Schanz D (2011) Estimation of tax values based on IFRS information: an analysis of German DAX30 and Austrian ATX listed companies. Account Europe 8:89–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2011.574362

Kinney MR, Swanson EP (1993) The accuracy and adequacy of tax data in COMPUSTAT. J Am Tax Assoc 117:121–135

Klemm A (2007) Allowances for corporate equity in practice. Cesifo Econ Stud 53:229–262

Krämer R (2015) Taxation and capital structure choice: The role of ownership. Scand J Econ 117:957–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12107

Kubick TR, Lockhart GB, Robinson JR (2020) Does inside debt moderate corporate tax avoidance? Natl Tax J 73:47–76. https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2020.1.02

Leone F, Zanotti E (2012) Notional interest deduction regime introduced. Eur Tax 52:432–436

Mackie-Mason JK (1990) Do taxes affect corporate financing decisions? J Finance 45:1471–1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1990.tb03724.x

Max MM, Wielhouwer JL, Wiersma E (2021) Estimating and imputing missing tax loss carryforward data to reduce measurement error. Eur Account Rev. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2021.1924812

Mills LF, Newberry KJ, Novack GJ (2003) How well do Compustat NOL data identify firms with U.S. tax return loss carryovers? J Am Taxation Assoc 25:1–17. https://doi.org/10.2308/jata.2003.25.2.1

Modigliani F, Miller M (1963) Corporate Income Taxes and the cost of capital: a correction. Am Econ Rev 53:433–443