Abstract

Despite the knowledge that women engage more frequently in multitasking than men when using media devices, no study has explored how multitasking impacts the brand attitude of this target audience. The investigation of gender effects in the context of media multitasking would not only provide a better understanding of the individual elements which influence brand attitude in media multitasking situations but would also guide marketers in their targeting strategies. Likewise, the investigation of the role of advertising appeals follows the current call to concentrate on the role of advertising in media multitasking situations. To address these research gaps, the current research conducted two experimental studies to offer a new perspective on the impact of gender differences in processing styles (heuristic vs systematic processing) and their interaction with different advertising appeals (rational vs emotional appeals) on brand attitude in media single and multitasking. Study 1 employs an online experiment (gender × viewing situation × advertising appeal). Results demonstrate that media multitasking negatively affects brand attitude, and that women have a lower brand attitude in a media multitasking situation compared to a single tasking situation, while emotional advertisements neither strengthen nor attenuate the negative impact of media multitasking on brand attitude. Study 2 employs a more controlled online experiment (gender × viewing situation × advertising appeal) with a different product category. The results reveal a moderating effect on the influence of media multitasking on brand attitude, as mediated through attention toward the ad. Hence, attention toward the ad has been identified as underlying mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to a recent ACNielsen report (The Nielsen Company 2018), 45% of audiences use a second screen while watching television, and another reveals that 178 million US adults regularly use another device (Independent 2019). Given the rising trend of media multitasking, this phenomenon (i.e. the simultaneous use of two or more devices) is a new form of audience behavior. Recent technological developments in the mobile phone industry support this notion: The world’s top mobile phone brands are developing (or have already launched) dual-screen smartphones (Forbes 2019).

Not only the evolving media landscape and the emergence of new digital devices but also the demographic change in the audience–teens can be considered as valuable target group due to their access to various media channels (The Nielsen Company 2009)–has transformed the traditional television viewing experience. While media multitasking can occur in various forms (e.g. listening to the radio or writing an email while watching television), a combination of the television and a digital device (a smartphone or tablet) is one of the most frequent combinations (The Nielsen Company 2018). This combination is of particular importance for marketers and advertisers in the context of media multitasking involving advertisements (i.e. at least one medium displays advertising content).

From a consumer perspective, media multitasking decreases the perceived duration of time and, consequently, has a positive impact on enjoyment (Chinchanachokchai et al. 2015). Indeed, one of the main reasons why consumers engage in media multitasking is the need for entertainment (Kononova and Chiang 2015; Kazakova et al. 2016). While several extant articles have explored the phenomenon of media multitasking from a consumer perspective (e.g. reduction of boredom, increase of entertainment), the current research follows a marketer’s perspective. The increased use of a second screen provides greater media-exposure time and so offers marketers and advertisers more opportunities to create exposure to advertising. Another advantage from a marketer’s perspective is that media multitasking can increase website traffic and sales (Liaukonyte et al. 2015), brand recall and brand attitude (Angell et al. 2016). Indeed, research reveals that the distraction caused by media multitasking can reduce counterarguing and hence increase persuasion and brand attitude (Jeong and Hwang 2015), especially for weak messages (Jeong and Hwang 2016). Nevertheless, Jeong and Hwang (2016) also note that at earlier stages of persuasion, the limited attention and reduced comprehension during media multitasking can decrease brand attitude. In a later meta analysis, reduced comprehension was found to significantly moderate the effect of media multitasking on persuasion, while no direct effect of media multitasking on brand attitude was observed (Segijn and Eisend 2019). In advancing the debate on the effect of media multitasking on brand attitude, we explore how different advertising appeals (emotional vs rational) impact women’s vs men’s brand attitude formation in media multitasking situations.

Given the relevance of brand attitude for predicting purchasing behavior (e.g., Garaus and Halkias 2019; Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez 2012), there has been a call to concentrate on attitudinal outcomes in media multitasking research (Kazakova et al. 2016). Further, extant research recognizes the need “to focus on the role of the ad to advance our understanding” (Duff and Segijn 2019, p. 33). In this regard, some studies have already explored how related (Angell et al. 2016; Smit et al. 2017) and congruent advertising (Beuckels et al. 2017) impacts on brand attitude formation during media multitasking. However, of more relevance for the current research are studies which explore the role of different advertising appeals, i.e. negative vs neutral appeals (Rubenking 2017) or desirability vs feasibility appeals (Kazakova et al. 2016). Kazakova et al. (2016) conclude that any positive effect of media multitasking on attitudinal outcomes can be diminished by advertising appeals requiring elaborate cognitive processes. In advancing this stream of research, we not only explore how another typology of different advertising appeals (emotional vs rational) impact on brand attitude formation during media multitasking, but also how these two different advertising appeals interact with gender.

The extant research calls for studies exploring how message design based on audience impact media multitasking effects (Duff and Segjin 2019). Such knowledge would help in the planning of advertising in terms of scheduling and content and enhance our understanding of the factors driving the effectiveness of advertisements during simultaneous media use. Related to this, several self-report studies (Gil de Zúñiga et al. 2015; Hwang and Jeong 2014; Kononova 2013; Kononova and Alhabash 2012; Pilotta et al. 2004) confirm that women engage more frequently in media multitasking than men. However, self-report studies have to be interpreted with caution as consumers might have a biased perception of their multitasking activities (Sanbonmatsu et al. 2013). Besides, there is also empirical evidence from an observational study which reports that, compared to men, women multitask more often when using digital devices (Voorveld and Viswanathan 2015). Women’s and men’s different processing strategies and their effect on brand attitude (Darley and Smith 2013) raise concerns about the effectiveness of advertising campaigns targeted at women in media multitasking situations.

By exploring how different types of advertising appeals (i.e. emotional vs rational appeals) influence female brand attitudes in single and multitasking media use, we offer several new contributions to the extant media multitasking literature. Firstly, we contribute to the debate over whether media multitasking affects brand attitude positively or negatively. Secondly, we offer a new perspective on the effects of media multitasking on brand attitude for a female audience by using the heuristic processing model. Thirdly, we consider the moderating role of different advertising appeals (emotional vs rational) on attitude formation for women vs men. Fourthly, after demonstrating that emotional advertising appeals lead to better brand attitudes for women in general, we investigate whether emotional appeals can diminish the negative effects of media multitasking on brand attitude. Lastly, we uncover the attention given to the advertisement as the underlying mechanism which explains the effect of media multitasking on brand attitude. Based on our findings, we have identified implications for marketers and media planners to help them to design advertising campaigns based on the target audience.

2 Literature review and hypotheses

2.1 Media multitasking and brand attitude

Media multitasking represents a special form of multitasking (i.e. the simultaneous performance of two tasks), in which individuals are exposed to two different sets of media content at the same time (e.g. Duff and Sar 2015; Pilotta et al. 2004). While media multitasking is not a new phenomenon, the emergence of new devices (smartphones and tablets) has revolutionized the experience of accessing media. Now, it is not only trading reports that highlight the change in viewing behavior to consume two or more media contents simultaneously (The Nielsen Company 2018). Media multitasking has attracted considerable academic attention over the past few years with different streams of research emerging from this. Scholars have concluded that individuals engage in media multitasking for both cognitive (Bardhi et al. 2010; Kononova and Chiang 2015) and emotional reasons (Chang 2016; Duff et al. 2014). Indeed, studies reveal that media multitasking is associated with a reduction in irritation with advertising (Beuckels et al. 2017) and increased enjoyment (Chinchanachokchai et al. 2015), both positive effects from a consumer’s perspective.

At the same time, research shows that the results of media multitasking on attitudinal outcomes are not straightforward (Segijn and Eisend 2019). Indeed, the findings of existing studies show inconclusive results for the impact of media multitasking on brand attitude.

On the one hand, the simultaneous combination of radio and online advertisements leads to a more favorable brand attitude than broadcasting advertisements only on the radio (Voorveld 2011). Likewise, research reveals that media multitasking decreases counterarguing (Jeong and Hwang 2015), which can cause favorable brand attitude during media multitasking. Counterarguing is a common strategy to resist persuasive advertising messages by deliberately thinking of an advertisement’s content to find arguments against the message (Segijn 2017). Drawing on the counterarguing inhibition hypothesis (Keating and Brock 1974), researchers argue that the distracting effect of media multitasking can reduce counterarguing and, in turn, positively affect brand attitude (Jeong and Hwang 2012). In media multitasking situations, the information processing ability and development of counter-arguments of consumers is limited, resulting in a more favorable brand attitude (Jeong and Hwang 2012). This effect is particularly present when the two media involved require resources from the same processing pool (i.e. when both media require visual processing) (Jeong and Hwang 2015; Segijn et al. 2016), as suggested by multiple resource theory (Wickens 1981, 2002).

On the other hand, when comparing a media multitasking situation with a single tasking situation, there is evidence that media multitasking negatively affects brand attitude (Bellman et al. 2017) due to reduced brand recognition (Segijn 2017; Segijn et al. 2017) and/or by limited attention (Segijn et al. 2017). Compared to a single screening of an advertisement, brand attitude formation was lower in both a related and unrelated multiscreening situation, with the negative effect being stronger for the unrelated version (Segijn et al. 2017).

Supporting this notion, a more recent literature review from Segijn and Eisend (2019) questions the finding from an earlier meta-analysis by Jeong and Hwang (2016) which claimed that media multitasking has a positive effect on attitudinal outcomes. Segijn and Eisend’s (2019) meta-analysis reveals that there is no significant effect of media multitasking on attitude, while also identifying several moderating factors. For instance, the requirement for behavioral responses resulted in a more negative effect on brand attitude, while familiarity with the brand increased brand attitude (Segijn and Eisend 2019). Likewise, another study reports that media multitasking does not cause a change in opinion (Jeong and Hwang 2016). The authors explain this result through two opposite processes. On the one hand, media multitasking reduces counterarguing, which encourages a change in opinion, but on the other hand, media multitasking also reduces comprehension, which has a negative effect. They also suggest that the level of distraction might determine the effect of media multitasking on a change in attitude. High levels of distraction might reduce counterarguing leading to a positive effect, while at the same time, high levels of distraction reduce comprehension to such an extent that it outweighs the potentially positive effect of reduced counterarguing (Jeong and Hwang 2016). In support of this, reduced comprehension has been found to be a significant moderator of the effect of media multitasking on persuasion in a meta analysis (Segijn and Eisend 2019) and research confirms that media multitasking negatively affects message comprehension (Van Cauwenberge et al. 2014). Other research supports these findings, showing that reduced counterarguing only benefits weak messages, while the lack of engagement with powerful content has a negative effect on the persuasiveness (i.e. brand attitude) of strong advertisements (Chowdhury et al. 2007).

Given the inconclusive findings yielded by the extant literature, not enough evidence exists to allow the creation of a confident hypothesis on the specific direction of the effect of media multitasking on brand attitude. The review of the literature suggests that the direction of any effect is strongly dependent on context factors, such as message appeal (strong vs weak), brand familiarity, as well as the extent to which media multitasking harms attention and message comprehension. Furthermore, the extent to which media multitasking causes a state of cognitive overload is a highly idiosyncratic issue which depends, among other things, on the individual characteristics of the subject. In line with the findings of Pantoja et al. (2016), the state of overload (moderate or high overload) might determine to some extent if media multitasking harms or benefits brand attitude. Therefore, we refrain from specifying a hypothesis but rather investigate the impact of media multitasking on brand attitude from an exploratory perspective by exploring the following research question:

RQ: How does media multitasking influence brand attitude?

2.2 Information processing, gender differences, and attitude formation

The reasons for attitude formation have attracted attention for decades. Several models dealing with persuasion have been developed which rely on the assumption that individuals make judgments based on the information available in the context of a decision. However, unlike cognitive theories which focus on the persuasive impact of the message itself (e.g. Hovland et al. 1953), dual-processing models of persuasion concentrate on factors other than those which are message-related to explain attitude formation. Two well-known examples of these are the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) and the heuristic-systematic model (HSM). The ELM (Petty and Cacioppo 1986) differentiates between two routes of processing depending on the level of individual involvement. Information processing via the central route implies the diligent and elaborate processing of information. This form of processing usually comes with a high level of involvement, and hence, the motivation to process the information. In contrast, peripheral processing occurs automatically and requires a minimum of cognitive effort (Petty and Cacioppo 1986).

The HSM (Chaiken 1980) also proposes two different routes, however, based on the sufficiency principle, the original idea stems from the assumption that the human mind sometimes uses the minimum required effort to process information (Chaiken and Ledgerwood 2012). In line with this assumption, the model proposes that in the interest of the economy, people strive to find a balance between the level of cognitive processing and motivational concerns (Chen and Chaiken 1999). The HSM offers a more detailed conceptualization of the two kinds of processing and explains the conditions under which either systematic or heuristic processing occurs (Todorov et al. 2002). Systematic processing represents careful thought and effort in elaborating on and reasoning through the arguments which are presented (Chaiken and Ledgerwood 2012). In contrast, heuristic processing requires less cognitive effort and occurs automatically. Heuristic processing involves focusing on simple cues which enables processing to take place even when individuals are not motivated to process the information content, or when people have little cognitive ability available (Chaiken and Ledgerwood 2012).

While both the ELM and the HSM assign the level of cognitive processing (i.e. heuristic vs systematic processing) to individual factors, such as motivation or the ability to process information, the selectivity model developed by Meyers-Levy and Maheswaran (1991) postulates general gender differences in information processing.Footnote 1 In essence, the selectivity model suggests that men do not use all the information available during decision-making but rely on heuristics. For men, single cues lead to a single inference, and they encode fewer of the claims made by advertising. Therefore, men engage in efficient, heuristic information processing (Darley and Smith 1993). In contrast, women rely on a systematic processing strategy. Hence, women attempt to assimilate all the available cues, leading to a greater encoding and elaboration of advertising claims. This use of all the available information implies increased effort and results in the comprehensive processing of the information (Meyers-Levy and Sternthal 1991). Hence, it can be expected that media multitasking is most likely to interfere with systematic rather than heuristic processing. Given the limited cognitive resources available for the processing of information (Lang 2000), and the requirement to share these resources if multiple tasks are performed simultaneously (Kahneman 1973), processing strategies which require effort (i.e. systematic ones) might be inhibited during media multitasking. Accordingly, it is reasonable to assume that, for women, systematic information processing is inhibited in media multitasking situations (Chen et al. 2009) since they tend to process all the available information in a comprehensive and detailed fashion. In this situation, it is reasonable to expect that there is a lower level of brand attitude formation when compared to single tasking situations, because of women’s inability to process the advertising message as they usually would (MacInnis and Jaworski 1989).

The lower cognitive effort associated with heuristic processing might aid the processing of multiple messages at the same time, even though this may be done less diligently. In this situation, the salient advertising cues are likely to be processed, since the cognitive resources required for processing are not exploited (MacInnis and Jaworski 1989). In other words, media multitasking seems to have contextual factors that might prevent individuals from engaging in detailed and complex processing. Importantly, these contextual factors also interact with gender differences in information processing. Papyrina (2013) found that women generate more message-related thoughts than men for advertisements which prompt deliberate processing (i.e. print media), while no gender difference could be discerned for a television advertisement (which is assumed to prompt peripheral processing). The author concludes that females engage in systematic processing when they have the opportunity to do so, however, if contextual factors hinder systematic processing, no gender differences can be seen. Accordingly, the current research postulates that in media multitasking situations women are forced to adapt their processing strategies to efficient, heuristic processing, which is similar to men’s processing strategies. Hence, brand attitude is expected to be the same for both women and men in media multitasking situations which prompt the same processing style. If media multitasking is considered to be a contextual factor, we assume that for women a systematic processing strategy has a positive impact on brand attitude development in single tasking situations, but not in a media multitasking situation.

H1. Women have a higher brand attitude in single tasking situations compared to multitasking situations. For men, we do not expect a difference in brand attitude between single tasking and multitasking situations.

2.3 Advertising appeals and gender differences

Existing research claims that men and women react differently to advertising content. For instance, Meyers-Levy (1988), employing an agentic perspective, report that men respond more favorably to advertisements promoting self-relevant information which relates to the self, while women evaluate advertisements more favorably that relate to the other. In support of this finding, a later study confirms that women respond with a more favorable attitude toward an advertisement when using help-other appeals, while men had a better attitude towards an advertisement with a help-self appeal. Some researchers claim that a different world view of men (justice) and women (caring) may explain this effect (Brunel and Nelson 2000). Furthermore, women respond less favorably than men to explicit sexual content in advertising, with this negative effect being reduced when the advertisement can be interpreted in terms of commitment (Dahl et al. 2009).

In general, the research discussed above confirms that appeals that match an individual’s values and attitudes result in more favorable responses. A common approach to categorizing advertising content is differentiating between emotional or rational appeals (Hornik et al. 2017; Golden and Johnson 1983). On the one hand, advertisements can convey feelings and prompt emotions by pointing to the subjective, intangible benefits of a product (Holbrook 1978). Emotional appeals rely on the hedonic and affective benefits of a product (Adaval 2001), and use sex and humor (Hornik et al. 2017). On the other hand, rational appeals induce elaborative thinking about the content. These advertisements appeal to the rationality of the audience (Golden and Johnson 1983) and often communicate utilitarian and practical features, such as product information or price (Amaldoss and He 2010).

An individual’s construal of the self in terms of femininity vs masculinity may explain differences in emotional (hedonic) vs rational (utilitarian) appeals. Respondents who construed themselves as masculine responded more favorably to rational than emotional appeals. These differences were absent for those who construed themselves in terms of both masculinity and femininity. It seems that appeals that match an indivdual’s construals of the self foster the encoding and processing of advertising messages (Chang 2016).

Following the findings above, it is reasonable to assume that women respond more favorably to emotional than rational appeals. Support for this notion also comes from elsewhere in the literature. It is claimed that because responsibility for childcare has largely fallen on women, they tend to be sensitive to the recognition and interpretation of facial expressions and emotions (Hampson et al. 2006; Meyers-Levy and Loken 2015). A wide-ranging literature review also reports compelling evidence for women’s well-developed recognition of nonverbal emotional communication (Christov-Moore et al. 2014). Other researchers have claimed that women are more emotional and respond more strongly to emotional appeals (Fisher and Dubé 2005), or that women attach greater value to their emotions compared to men (Dubé and Morgan 1998). Drawing on the notion that advertising is most effective when advertising appeals match viewers' gender identity (Feiereisen et al. 2009), we propose that

H2. Compared to men, women have a higher brand attitude when exposed to emotional appeals. For rational appeals, we expect no difference in brand attitude between men vs women.

We further assume that the negative effect of media multitasking on women’s attitude formation is diminished for emotional vs rational advertising appeals. Extant research acknowledges that “MMT can be seen as a result of the interaction between a person’s goals and interests and the features/capabilities of media devices and content” (Duff and Segijn 2019, p. 30). These studies explored how related content displayed on the two media devices in media multitasking impact recall, recognition, and brand attitude (Angell et al. 2016; Smit et al. 2017). Related research reveals that the lowest advertising irritation is achieved with a congruent animated banner and high task relevance in media multitasking situations (Beuckels et al. 2017). Negative messages lead to higher enjoyment in media multitasking conditions as compared to neutral messages (Rubenking 2017). Kazakova et al. (2016) reveal that any positive effect of media multitasking on attitudinal outcomes can be diminished by advertising appeals requiring elaborate cognitive process.

In line with this notion, the ELM suggests that central and deliberate processing will only occur if individuals have the opportunity to do so (Petty and Cacioppo 1986). This effect is enhanced for individuals who usually engage in systematic processing (i.e. women) since it requires more cognitive effort compared to heuristic processing (i.e. carried out by men). In line with this reasoning, we do not expect any gender differences in brand attitude in media multitasking situations with emotional appeals. The reasoning behind this assumption is as follows: Although we assume that emotional appeals lead to more favorable brand attitude for women (H2), we further expect that this positive effect diminishes for women in situations of media multitasking (H1). Women’s systematic processing strategy is expected to be inhibited in media multitasking situations; however, this effect diminishes when the appeal matches viewers' gender identity. In sum, the negative effect of media multitasking and the positive effect of emotional appeals are expected to outbalance each other, leading to no difference in attitude formation between women and men when being exposed to emotional appeals in media multitasking situations.

Indeed, emotional advertising appeals can be processed via the peripheral route, which allows for unconscious processing and uses considerably less cognitive effort compared to rational appeals (Petty and Cacioppo 1986). In a multitasking task situation, the activation of automatic and quick processing caused by emotional stimuli benefits the processing of information (Shiv and Fedorikhin 1999; Rottenstreich et al. 2007). Hence, emotional appeals prevent women to some extent from engaging in systematic processing but allow them to process the emotional content heuristically. Nevertheless, the other medium’s content most likely still prompts systematic processing to some extent, which diminishes any positive effect of emotional appeals on brand attitude (as discussed in H2). Accordingly, men and women are expected to have a similar brand attitude when exposed to emotional advertising content.

However, exposing women to rational advertising appeals in media multitasking situations results in a greater exploitation of cognitive resources when compared to men, since women will process information systematically, while men will pursue a heuristic processing strategy. Following the ELM, rational advertising appeals require cognitive processing through the central route, and hence, more elaboration compared to emotional appeals (Petty and Cacioppo 1986). Elaborate thinking about rational appeals would interfere with the systematic processing strategy of women, since rational appeals would cause a further exhaustion of cognitive resources. Indeed, this systematic information-processing strategy might be less efficient in situations of resource depletion (Meyers-Levy and Loken 2015). In the context of product placements, research confirms a less pronounced positive effect of an overload vs load condition on brand attitude for intrusive product placements (Pantoja et al. 2016). The authors conclude that it makes a difference if individuals evaluate a brand in either high or moderate load conditions. Moderate load conditions hinder the activation of associative networks, which also means that comparison with competitor brands is less likely. However, during cognitive overload, attention is disrupted and hinders the audience from processing the product placement (Pantoja et al. 2016). While the heuristic processing strategy of men would protect them from a cognitive overload when they are exposed to rational advertising appeals, women’s systematic processing style probably causes cognitive overload during media multitasking. Accordingly, we propose that

H3a. In media multitasking situations, women have a lower brand attitude when exposed to rational appeals compared to men. For emotional appeals, we do not expect a difference in brand attitude between men and women.

H3b. In single tasking situations, women have a higher brand attitude when exposed to emotional appeals compared to men. For rational appeals, we do not expect a difference in brand attitude between men and women.

3 Study 1

3.1 Design and participants

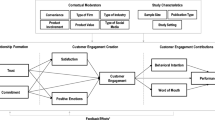

To test our research framework (see Fig. 1), we conducted an online experiment employing a 2 (gender: female vs male) × 2 (viewing situation: media single tasking vs multitasking) × 2 (advertising appeal: emotional vs rational) between-subjects design. While we measured for gender in our questionnaire, the viewing situation and advertising appeal were manipulated. The online experiment provided a natural viewing situation for participants and benefited from a high external validity. Since the combination of television and mobile phones represents one of the most frequent media multitasking situations, we asked participants to watch a television program with advertisements on their computer screen. This program was fully integrated into the online survey, started automatically, and had to be watched in its entirety to continue with the following questionnaire. In the media multitasking situation, participants were asked to browse an Instagram site on their smartphone while watching the television program. A convenience sample of 156 participants (60% female, Mage = 31.72) acquired by students as part of a project was assigned randomly to one of four experimental groups.

3.2 Pre-study and stimulus material development

To disguise the purpose of the experiment, an advertisement containing the manipulation of the advertising appeal was integrated into a media report on the travel into space of Alexander Gerst in 2018. The research team, along with several research assistants, selected this report because it was classified as interesting but not stimulating.

The selection of our target brand for the advertisement was guided by availability and the credibility of existing emotional and rational advertisements. This was an unexpected challenge as companies seem to use an emotional or a rational advertising strategy, but do not use both advertising appeals in their communication strategy for a specific product. Additionally, a lot of rational advertisements communicate information about the product within a highly emotional setting. Therefore, we had difficulties of identifying clear examples of emotional vs rational advertisements from one company, which limited the scope of available stimulus material.

We finally selected one emotional and one rational television spot from Ja! Natürlich (a producer of dairy products) to manipulate the advertising appeals. The main message of both advertisements focused on the benefits of the product (i.e. organic milk). While the emotional spot communicates the benefits of the product by showing the origin of the milk (e.g. a natural setting, cows), the rational spot highlights these benefits by providing this product information as factual knowledge. Overall, both spots provided strong arguments for the brand being promoted. A pre-study (n = 26, 50% female, Mage = 31.62) which exposed participants to either an emotional or a rational advertisement of Ja! Natürlich revealed that the advertisements were evaluated as appropriate for the purpose of our research. More precisely, the emotional advertisement of Ja! Natürlich (Ja Natürlich 2009) was evaluated as more appropriate for conveying emotions (Memo 5.07 > Mrat 2.91; t(24) = 3.85, p < 0.01) while the content of the rational advertisement of Ja! Natürlich (Ja Natürlich 2016) received higher evaluations on the rational scale (Mrat 5.73 > Memo 3.67; t(24) = 2.78, p < 0.01). Both advertisements were easy to understand (Memo 6.23 = Mrat 6.05; t(24) = 0.50, p = 0.62), and the brand appeared as both of high quality (Memo 5.67 = Mrat 5.73; t(24) = -0.12, p = 0.91) and credible (Memo = 4.73 vs Mrat = 5.00; t(24) = -0.46, p = 0.65).

Under both advertising appeal conditions (i.e. emotional vs rational), participants were exposed to only one advertisement from Ja! Natürlich. The television spot—announced by an “Only one spot” sequence—started at the two-minute mark and continued for 50 s. After the advertisement, the media report continued for three minutes. As the subsequent questionnaire measured the attitudinal responses of the participants to the brand shown in the advertisement, this last part of the media report served as a filler (Kazakova et al. 2016).

3.3 Procedure and measures

The link to the online experiment was sent out to participants, allowing them to participate in their homes in a natural viewing environment. To ensure participation on a PC or laptop (and not on a smartphone), the instructions asked participants to open the link only on a PC or a laptop in a quiet room, without any other noises or other people. Afterwards, participants were asked to check the quality of their internet connection as well as the sound. Then, the survey tool automatically started the television program. Under all conditions, a short introduction informed participants that they would see a media report, and that they should be relaxed but attentive while watching it.

In contrast to the single tasking situation, participants in the multitasking situation received the additional information that they should open a website on their smartphone. A mockup of an Instagram page designed for this study served as stimulus material for the second screen (i.e. the smartphone). Extensive discussions guided the final selection of the stimulus material. More specifically, the possible contents of the posts were discussed with other researchers. In addition, we investigated which kind of posts receive many likes on Instagram, which we used as proxy for interest. Based on this, we decided to use ninety Instagram posts showing photographs of attractive places, food, natural surroundings, houses, or home furnishings, together with the number of likes and a short message as stimulus material. Three research assistants familiar with Instagram were responsible for putting together the posts.

We then exposed the participants to the two content tasks simultaneously. While watching the television program, they were asked to make themselves as comfortable as possible, as if they were watching television; we asked them to be relaxed but attentive. Participants were encouraged to simultaneously watch the media report on space travel and scroll through the Instagram site on their smartphone. We also instructed participants to pay equal attention to the media report and the Instagram site during exposure to the stimulus material so they would not forget to do one of the two tasks (Kazakova et al. 2016). Under the single tasking conditions, participants were not permitted to interact with any other media device while watching the television program.

After exposure to the stimulus, all the participants were transferred automatically to a short questionnaire. Seven-point scales collected information about brand attitude (four items; Holbrook and Batra 1987). The same items used in the pre-study were used to assess the emotional and rational appeal of the advertisements. We also included items to measure consumers’ attention allocation, focused attention (four items; Novak et al. 2000), brand recognition and recall, brand familiarity and importance of the product category which was advertised to control for possible confounding variables. To control whether participants in the media multitasking condition followed our instructions to engage with the Instagram page while watching the video, an attention check was included in the survey asking respondents about the content of the posts. Finally, we collected information about gender, age, and income and asked participants whether the survey was interrupted at any time and whyFootnote 2 (see “Appendix” for an overview of measures and properties).

3.4 Results

3.4.1 Preliminary analysis

The manipulation of the advertising appeal was successful. The emotional advertisement is evaluated as more appropriate for conveying emotions (Memo 4.85 > Mrat 2.97; t(139) = 6.76, p < 0.01) while the content of the rational advertisement receive higher evaluations on the rational scale (Mrat 5.51 > Memo 3.00; t(139) = 9.86, p < 0.01).

Under the media multitasking conditions, attention allocation for the media report vs the Instagram site is similar (Mmulti_report = 52% vs Mmulti_insta = 48%; t(71) = 0.94, p = 0.35); participants performed the two tasks simultaneously and did not “forget” one of the two tasks.

3.4.2 Hypotheses testing

To test our research framework, we conducted an ANCOVA with brand attitude as the dependent variable and viewing situation (media single tasking vs multitasking), advertising appeal (emotional vs rational), and gender (female vs male) as the independent variables. Brand familiarity and importance of the product category being advertised served as covariates in our model. Brand familiarity shows a significant positive influence on brand attitude (F(1, 130) = 7.58, p < 0.01). In contrast, the importance of the product category is not significant (F(1, 130) = 0.97, p = 0.33). Table 1 summarizes the ANCOVA results.

The results demonstrate that the viewing situation has an influence on brand attitude. More specifically, participants under the multitasking conditions evaluate brand attitude more negatively when compared to the single tasking conditions (Mmulti 4.65 < Msingle 5.36; F(1, 130) = 8.34, p < 0.01).Footnote 3 Hence, we can answer our research question, i.e., that media multitasking has a negative influence on brand attitude.

We also test whether focused attention mediated the effect of multitasking on brand attitude by estimating a mediation model using Hayes’ (2018) PROCESS macro in SPSS (model 4; bootstrap sample n = 5000). Results reveal only a direct effect, as stated in our research question (− 0.67, SE = 0.21, p < 0.01, 95% CI [− 1.09, − 0.25]) and no indirect effect via focused attention (− 0.04, SE = 0.04, 95% BCBCI [− 0.14, 0.03]). Hence, the effect of multitasking on brand attitude does not change with focused attention as a mediator. Additionally, we run this model for all subsequent hypotheses and do not find indirect effects via focused attention.

The negative effect of media multitasking interacts with gender as we observe an interaction between the viewing situation and gender (F(1, 130) = 6.96, p < 0.01). Corroborating H1, our results show that, among women, brand attitude is higher in the single tasking situation compared to the multitasking situation (Mwomen_single 5.66 > Mwomen_multi 4.50; t(80) = 4.11, p < 0.01). In contrast, no difference in brand attitude is observed for male viewers and their viewing situation (Mmen_single 4.91 = Mmen_multi 4.85; t(57) = 0.20, p = 0.84). Although not hypothesized, we also test whether women vs men differ in brand attitude in the single tasking vs multitasking situation. Results show that women and men differ from each other in brand attitude in the single tasking condition (Msingle_women 5.66 > Msingle_men 4.91; t(67) = 2.38, p < 0.05) but not in the media multitasking situation (Mmulti_women 4.50 = Mmulti_men 4.85; t(70) = 1.19, p = 0.24).

Women and men not only respond differently to the viewing situation that they are exposed to, but also to the advertising appeals. The results reveal a significant interaction between advertising appeal and gender (F(1, 130) = 4.21, p < 0.05). Although only significant at a level of 10%, we find that women demonstrate higher brand attitude compared to men when exposed to emotional advertising appeals (Memo_women 5.19 > Memo_men 4.58; t(66) = 1.83, p < 0.10). Additionally, we observe similar levels of brand attitude among women and men when promoting the brand with rational content (Mrat_women 4.97 = Mrat_men 5.15; t(71) = − 0.58, p = 0.56). H2 is suggestive although not statistically significant.

Our results demonstrate that women have a lower brand attitude in a media multitasking situation compared to a single tasking situation and that women in general respond with a slightly more positive brand attitude to emotional advertising appeals compared to men. However, the positive effect of emotional appeals for women changes in a media multitasking situation. Hence, the further analyses follow a stepwise procedure to investigate the different patterns between women and men to rational vs emotional appeals in the two conditions (i.e. media multitasking vs single tasking). More specifically, the analyses start with a comparison of female and male responses to rational advertising appeal in media multitasking situations (H3a). In a second step, the analyses investigate the single tasking situation and the comparison of female and male responses to emotional advertising appeal (H3b).

In confirmation of H3a, we observe that female multitaskers indicate a significantly lower brand attitude when prompted with rational content compared to the male audience (Mmulti_rat_women 4.30 < Mmulti_rat_men 5.00; t(35) = 1.80, p < 0.05). Comparing women’s brand attitude in such a situation with their exposure to rational advertising appeals in general (investigated in H2) shows a decrease of brand attitude (Mmulti_rat_women 4.30 < Mrat_women 4.97). Additionally, women and men demonstrate similar levels of brand attitude in media multitasking situations when exposed to emotional advertisements (Mmulti_emo_women 4.71 = Mmulti_emo_men 4.68; t(33) = 0.07, p = 0.95). Means indicate that the positive effect of emotional advertisements on brand attitude (investigated in H2) is reduced for women in media multitasking situations (Mmulti_emo_woman 4.71 < Memo_women 5.19). However, brand attitude does not decrease below the level of brand attitude found in media multitasking in general (H1) (Mmulti_emo_women 4.71 = Mmulti_women 4.50). Therefore, it can be said that emotional advertisements neither strengthen nor attenuate the negative impact of media multitasking on brand attitude. It seems that the negative impact of media multitasking on brand attitude dominates women’s attitude formation to such an extent that emotional advertising appeals cannot diminish this effect.

In contrast, and collaborating H3b, in the single tasking situation we observe a different pattern. Female multitaskers indicate a significantly higher brand attitude when prompted with emotional content compared to the male audience (Msingle_emo_women 5.68 > Msingle_emo_men 4.46; t(31) = 2.47, p < 0.05). Additionally, women and men demonstrate similar levels of brand attitude in single tasking situations when exposed to rational advertisements (Msingle_rat_women 5.64 = Msingle_rat_men 5.30; t(34) = 0.87, p = 0.39). While in the media multitasking situation women demonstrate lower brand attitude compared to men when exposed to rational advertising content, the single tasking situation reveals that women exhibit higher brand attitude compared to men for emotional advertisements. Figure 2 provides a summary of the results.

Contrary to the extant research (Segijn 2017; Segijn et al. 2016), our study neither found a mediating effect of brand memory measures (recall and recognition) nor a mediating effect of attention. One possible explanation for the absence of any mediating effect might be that individuals’ focused attention on a general level was sufficient to identify the correct brand, however, the state of overload during multitasking might disrupt attention at the moment of advertising exposure (i.e. attention toward the advertisement; Pantoja et al. 2016). Hence, it might be that limited attention while watching the ad (and not the video in general) explains any negative effect of media multitasking on brand attitude. Study 2 accounts for this possible explanation. Additionally, there remain two other limitations of study 1, which are addressed in study 2. First, we manipulated only a single message per condition, which limits the general applicability of our findings. It is possible that the effect is driven by the product category or the topic of the message and not by our manipulation of the viewing situation. Second, our stimulus material required participants to use their smartphone actively to create a media multitasking situation, something which could not be controlled for. To overcome these limitations, study 2 used advertisements from a different product category (air freshener) and a more controlled experimental setting. More specifically, we created a stimulus showing both a TV screen and a smart phone in the media multitasking condition, while only the TV screen was shown to respondents in the single tasking situation. Furthermore, we assessed attention given to the ad as a possible underlying mechanism explaining any possible effects of media multitasking on brand attitude.

4 Study 2

4.1 Design and participants

Study 2 employed a 2 (gender: female vs male) × 2 (viewing situation: media single tasking vs multitasking) × 2 (advertising appeal: emotional vs rational) between-subjects design. In the media multitasking condition, participants were shown a TV screen with a smartphone in the foreground, and the content (a newspaper article) scrolled automatically on the smartphone to create a realistic viewing condition. In the single tasking situation, only the TV screen (without the smartphone) appeared. The full TV screen was visible in both conditions. A convenience sample of 211 participants (40% female, Mage = 40.54) recruited through the online panel platform Clickworker was randomly assigned to one of four experimental groups in a home setting.

4.2 Pre-study and stimulus material development

A shorter version of the same media report used in study 1 was used as stimulus material. As a target brand for the advertisement we selected one emotional and one rational TV spot from Air Wick (a producer of air freshener) to manipulate the advertising appeals. The main message of both advertisements focused on the benefits of the product (i.e. fresh air). While the emotional spot communicates the benefits of the product by relating the product to a natural setting in the mountains, the rational spot highlights these benefits by providing some product information (i.e. that it contains essential oils).

A pre-study (n = 103, 37% female, Mage = 39.72) exposed participants to either the emotional or the rational advertisement and revealed that the advertisements were evaluated as appropriate for the purpose of our research. The emotional advertisement is evaluated as more appropriate for conveying emotions (Memo 4.96 > Mrat 4.12; t(101) = 2.72, p < 0.01) while the content of the rational advertisement receives higher evaluations on the rational scale (Mrat 4.92 > Memo 3.37; t(101) = 4.58.42, p < 0.01). Both advertisements are perceived as similarly interesting (Memo 3.46 = Mrat 3.49; t(101) = -0.08, p = 0.94) and participants indicate that the advertisements match the brand (Memo 5.59 = Mrat 5.35; t(101) = 0.98, p = 0.33).

4.3 Procedure and measures

The procedure of study 2 was similar to the procedure of study 1 with a few exceptions. First, the media report with the advertisement was displayed on a picture of a TV screen, to generate a more realistic viewing situation (Garaus et al. 2017). Second, instead asking respondents to use their own smartphones to create a media multitasking situation, we manipulated the media multitasking directly via the stimulus material to allow more control over the experimental conditions. More specifically, we manipulated the media multitasking by including a smartphone in the stimulus material (on the right-hand side of the TV screen). To enhance the realism of the stimulus material, a hand held the smartphone to create a view which is typical of multitasking with a TV screen and a smartphone. Third, instead of an Instagram page, the smartphone automatically scrolled through a newspaper article to ensure a realistic reading situation.

After exposure to the stimulus, all the participants were transferred automatically to a short questionnaire. Two attention checks automatically ended the survey for those participants who chose the wrong content for the media report (and the newspaper article in the media multitasking condition). Subsequent questions assessed the emotional and rational appeal of the advertisements, brand attitude, gender, age, and income. To control for possible confounding variables, we included items for brand familiarity, the importance of the product advertised, and the level of distraction caused by other people and noises while filling out the questionnaire. Additionally, participants indicated their media multitasking behavior in the “real world”.Footnote 4 Furthermore, we included an item assessing attention given to the advertisement and attention allocation to explore any mediating effect of limited attention during media multitasking situations on brand attitude (Jeong and Hwang 2016; see “Appendix”).

4.4 Results

4.4.1 Preliminary analysis

The manipulation of the advertising appeal was successful: Respondents evaluated the emotional advertisement as conveying more emotional information than the rational one (Memo 4.96 > Mrat 4.34; t(164) = 2.37, p < 0.05) while the rational advertisement received higher evaluations on the rational assessment scale (Mrat 3.89 > Memo 3.31; t(164) = 2.33, p < 0.05). Media multitaskers allocated almost the same amount of attention to the TV report and the news article (Mmulti_tvreport 49% = Mmulti_newsarticle 60%; t(87) = -1.63, p = 0.11). However, compared to the single taskers, media multitaskers were shown to devote less attention to the TV advertisement (Mmulti 3.08 < Msingle 4.91; F(1, 164) = 40.87, p < 0.01).

4.4.2 Hypotheses testing

To test the effect of media multitasking on brand attitude (RQ), an ANCOVA was estimated, with brand attitude as the dependent variable and viewing situation (media single tasking vs multitasking), advertising appeal (emotional vs rational), and gender (female vs male) as the independent variables. Brand familiarity, the importance of the product advertised, and distraction served as covariates. While brand familiarity (F(1, 155) = 0.80, p = 0.37) and distraction (F(1, 155) = 0.34, p = 0.56) were not significant, the importance of the product showed a significant positive influence on brand attitude (F(1, 155) = 26.55, p < 0.01). Table 2 summarizes the ANCOVA results.

Validating the results from study 1, these results confirm that media multitasking has a negative influence on brand attitude (RQ). Media multitaskers evaluate brand attitude more negatively compared to single taskers (Mmulti 4.68 < Msingle 4.94; F(1, 155) = 4.83, p < 0.05).

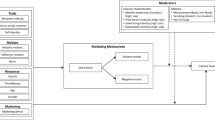

Contrary to H1, we do not observe an interaction between viewing situation and gender (F(1, 155) = 0.15, p = 0.70). However, an inspection of the mean values indicates that the effect tends to move in this direction. For women, brand attitude is higher in the single tasking situation compared to the multitasking situation (Mwomen_single 5.06 > Mwomen_multi 4.75; t(64) = 0.88, p = 0.38). In contrast (and in line with the results from our first study), no difference in brand attitude is observed for male viewers and their viewing situation (Mmen_single 4.86 = Mmen_multi 4.60; t(98) = 1.13, p = 0.26). To further explore the unexpected absence of the effect we had predicted, we investigated the mediating role of attention toward the ad on the effect of viewing situation on brand attitude, as moderated by gender. We estimated a moderated mediation model (Model 8, PROCESS, 10.000 bootstrapping samples, 95% confidence intervals) with the viewing situation as an independent variable (single tasking served as reference category), attention toward the ad as a mediating variable, brand attitude as a dependent variable and gender as a moderating variable (media multitasking → attention toward the ad → brand attitude; gender moderates the effect of media multitasking on attention toward the ad and on brand attitude). The results confirm a mediating effect for both women (− 0.84, CI[− 1.17, − 0.55]) and men (− 0.47, CI[− 0.78, − 0.22]). The index of moderated mediation was significant [0.37, CI[0.02, 0.72]), indicating that the mediating effect of attention toward the ad is stronger for women than men. This result is also confirmed by a pairwise contrast between the conditional indirect effects (− 0.47, CI[0.02, 0.72]). Media multitasking did not impact brand attitude directly (0.90, p = 0.12), pointing to full mediation through attention allocation. This result has to be interpreted as follows: Although gender seems to moderate the effect of media multitasking on brand attitude, it also seems that gender alone cannot account for this effect. Instead, attention toward the ad has to be considered as an underlying mechanism. This finding is in line with the extant literature, suggesting that limited attention can decrease brand attitude at earlier stages of persuasion (Jeong and Hwang 2016), and that cognitive overload causes distraction and hinders the processing of promotional content (Pantoja et al. 2016). Our results suggest that women’s systematic processing style requires more cognitive resources for processing the newspaper article on the smartphone, and that the distraction caused by media multitasking hurts women’s deliberate information processing.

Corroborating H2, our results show that women and men respond differently to the advertising appeal they are exposed to. The results reveal a significant interaction between advertising appeal and gender (F(1, 155) = 4.78, p < 0.05). Women demonstrate higher brand attitude compared to men when exposed to emotional advertising appeals (Memo_women 5.31 > Memo_men 4.66; t(82) = 2.52, p < 0.05). In contrast, we observe similar levels of brand attitude among women and men for the rational content (Mrat_women 4.55 = Mrat_men 4.85; t(80) = -1.00, p = 0.32).

For H3a, we observe that female multitaskers indicate a lower brand attitude when prompted with rational content compared to a male audience (Mmulti_rat_women 4.46 < Mmulti_rat_men 4.85; t(30) = -0.95, p = 0.35). However, these differences did not reach significance. Additionally, women and men demonstrate similar levels of brand attitude in media multitasking situations when exposed to emotional advertisements (Mmulti_emo_women 5.09 = Mmulti_emo_men 4.39; t(32) = 1.83, p = 0.08).

To account for attention toward the ad as an underlying mechanism, as already confirmed when testing H1, we estimated a conditional moderated mediation analysis using PROCESS (model 13, 10,000 bootstrapping samples, 95% CI) with the viewing situation as an independent variable, attention toward the ad as a mediating variable, brand attitude as a dependent variable, gender as a moderator variable and advertising appeal as a moderating variable on the conditional effect of gender on attention toward the ad (viewing situation → attention toward the ad → brand attitude, gender moderates the impact of the viewing situation on attention toward the ad and on brand attitude, and advertising appeal moderates the conditional effect of gender). The results confirm that women’s brand attitude (− 0.75, CI[− 1.18., − 0.35]) is lower than men’s brand attitude (− 0.58, CI[− 0.98, − 0.24]) when exposed to rational appeals in media multitasking conditions (compared to single tasking conditions). However, contrary to our expectations, this effect was not significant (CI, [− 0.36, 0.65]). A possible explanation for the absence of this effect might rely in study 2’s stimulus material: The rational advertisement received considerably higher evaluations in terms of emotionality in study 2 compared to study 1 (Mrational_emotionality_study1 = 3.00 vs Mrational_emotionality_study2 = 4.34). Hence, it seems that the rational advertisement (although being rated more rational than emotional) also contains emotional elements, which prompt almost the same informational processing for women in both viewing conditions.

Likewise, we observed a significant difference for emotional appeals for both women (− 0.91, CI[− 1.13, − 0.53] and men (− 0.32, CI[− 0.69, − 0.01]), and this difference was significant (contrast: − 59, CI[0.14, 1.06]). Accordingly, we could not confirm H3a and produce similar findings as in study 1. Emotional appeals neither strengthen nor attenuate the negative impact of media multitasking on brand attitude, as revealed by pairwise contrasts between the conditional indirect effects of emotional vs rational appeals for women (contrast: − 0.17, [− 0.33, 0.68]).

In the single tasking situation (H3b) we observe that female multitaskers indicate a higher brand attitude when prompted with emotional content compared to the male audience (Msingle_emo_women 5.43 = Msingle_emo_men 4.88; t(48) = 1.62, p = 0.12), however, this effect was not significant. When accounting for attention toward the ad as a mediator with the same conditional moderated mediation analysis as for H3a (with the exception that media multitasking now serves as a reference category), this difference becomes significant. More specifically, when comparing the single tasking condition to the multitasking condition, women respond more favorably to emotional content (0.77., CI[0.43, 1.13] compared to men (0.32, CI[0.04, 0.64]. This difference was significant as revealed by pairwise contrasts between the conditional indirect effects (CI[− 0.86, − 0.05]) and a significant index of conditional moderated mediation for emotional appeals (− 0.45, CI[− 0.86, − 0.05]) and a non-significant index of conditional moderated mediation for rational appeals (− 0.02, CI[− 0.46, 0.47]). As indicated by the later index, mean comparisons confirm that women and men demonstrate similar levels of brand attitude in single tasking situations when exposed to rational advertisements (Msingle_rat_women 4.61 = Msingle_rat_men 4.84; t(48) = − 0.55, p = 0.59). The indirect effect of single tasking (as compared to media multitasking) on brand attitude through attention towards the advertisement and as moderated by gender and the advertising appeal did not differ significantly (CI[− 0.46, 0.47]) between women (0.70, CI[0.35, 1.09]) and men (0.68, CI[0.35, 1.06]). These results confirm H3b.

5 Discussion

Media multitasking has become omnipresent while watching television. A recent news article states that media multitasking is “so common that an estimated 178 m US adults regularly use another device while watching TV” (Szameitat 2018). While the effects of media multitasking on various cognitive outcomes have already attracted considerable attention (Jeong and Hwang 2015; Kazakova et al. 2016), no study has explored how the effects of emotional vs rational advertising appeals on brand attitude vary between female and male viewers. Moreover, although studies agree that women engage more frequently in media multitasking (e.g. Gil de Zúñiga et al. 2015; Hwang and Jeong 2014; Kononova 2013), the literature lacks a nuanced perspective on strategies to diminish the negative effects of multiscreen use on female brand attitude formation. The current research fills this gap by offering a new explanation of the differing effects of media multitasking on brand attitude between women and men. More specifically, we draw on the HSM to explain why women’s formation of brand attitude is hindered in media multitasking situations, while accounting for advertising appeal as a contextual factor and attention toward the advertisement as a mediating mechanism affecting the results. The finding of an online experiment confirms our assumptions that the systematic processing strategy used by women benefits brand attitude formation in single tasking situations, but negatively affects brand attitude in media multitasking conditions.

5.1 Theoretical and practical implications

This study reveals that media multitasking negatively affects brand attitude formation. Hence, our results advance the existing literature on advertising by offering deeper insights into how different viewing situations impact brand attitude, something which constitutes an important determinant of purchasing behavior (e.g. Garaus and Halkias 2019) and the formation of consumer-based brand equity (e.g. Ansary and Hashim 2018).

Although not incorporated into the hypotheses, it is surprising that we did not find any effect of media multitasking on brand recall and recognition. This is interesting since both have been identified as mediators explaining the negative effects of media multitasking on brand attitude (Segijn 2017; Segijn et al. 2016). Since we observed a negative effect, reduced counterarguing (Jeong and Hwang 2016), the second mechanism explaining attitude change in media multitasking conditions, does not represent an explanation. Using the extant literature, we argue that the cognitive load caused by media multitasking hinders women’s systematic processing by disrupting women’s attention (Pantoja et al. 2016; Yoon et al. 2011). As a consequence, brand attitude formation can benefit from the effort and deliberate processing strategy used by women only in single tasking situations. On the contrary, the heuristic processing strategy used by men is not affected by media multitasking situations, since heuristic processing is associated with lower cognitive effort and automatic processing (Chaiken and Ledgerwood 2012). Men’s reliance on easy cues causes less cognitive overload, and as revealed in study 2, allows them to devote more attention to the advertisement. This explanation would also explain Garaus et al.’s (2017) findings, which report that women’s message recall was significantly better compared to men’s recall in single tasking situations, while no significant difference occurred in media multitasking situations. Adding to the literature on media multitasking, we demonstrate that this effect not only exists for message recall but also for brand attitude, and that this effect is mediated by attention toward the advertisement. For the latter, it is important to note that general attentional measures (i.e. focused attention) do not serve as a mediator (study 1), while attention toward the ad explains the moderating effect of gender on the effect of media multitasking on brand attitude (study 2).

In addition to this new theoretical framework explaining how women’s and men’s processing styles form brand attitude in single tasking and multitasking situations, our study also offers new insights into the role and influence of gender on emotional and rational advertising appeals in media multitasking situations. In doing so, we follow the call to explore how advertising content as context factor influences an audience’s responses to advertising in media multitasking situations (Duff and Segijn 2019). We confirm our theoretical reasoning that women respond more favorably to emotional advertising appeals than men. We summarize extant research reporting different responses of men and women to a variety of content appeals (Hampson et al. 2006; Meyers-Levy and Loken 2015). This guided our theoretical reasoning that women evaluate advertising by relying more on emotional than rational appeals. The argument is based on both a preference for content that matches a consumer’s identity (Feiereisen et al. 2009) and evolutionary theory (Hampson et al. 2006; Meyers-Levy and Loken 2015). We propose that this positive effect remains stable in media multitasking situations. The findings of study 1 supported our assumption that, in contrast to rational appeals, emotional appeals do not further increase the cognitive load in media multitasking situations. Hence, while emotional appeals can be processed automatically by women, the additional cognitive effort required to process rational appeals systematically harms brand attitude formation. This finding is in line with our theoretical reasoning based on the selectivity model (Meyers-Levy and Maheswaran 1991), i.e. that the deliberate effort required for rational advertising appeals exceeds the cognitive processing capabilities for holistic processors (i.e. women), but not for analytical processors (i.e. men). However, study 2 did not validate these findings. Neither emotional nor rational appeals attenuate or strengthen the effect of media multitasking on brand attitude. The comparably high evaluation of the study-2 rational advertisement in terms of emotionality might explain this finding. It seems that if rational appeals also contain emotional elements, the negative effect of rational appeals on women’s processing can be counteracted. This finding is of high relevance from a practical perspective, since it allows advertisers to rely on rational content as well, even when targeting women in situations where media multitasking is likely to occur. However, media planners have to bear in mind that–on a general level–our study reveals that media multitasking affects brand attitude formation negatively. Accordingly, marketers need to be aware that broadcasting advertisements in situations where media multitasking is likely to occur hinders brand attitude formation. This knowledge should impact media planning strategies related to the target audience's reach. Furthermore, our research follows the call to understand the media multitasking audience in terms of segmentation, which helps to determine how individual consumers will respond to the messages encountered while multitasking (Duff and Segijn 2019). Marketers and media planners must be aware that women and men process advertising content in single and media multitasking situations differently. Neither female nor male viewers exhibit a lower brand attitude when exposed to emotional advertising appeals in media multitasking situations compared to single tasking situations. However, women evaluated the brand as being significantly worse when exposed to an advertisement with a rational appeal during media multitasking.

5.2 Limitations and future research

Despite the insights this study offers, our research has met with some limitations, some of which provide promising avenues for future research. Although our online experiment benefits from a high internal validity, and we put great effort into creating a realistic viewing situation, certain limitations of this experimental approach have to be noted. First, to control the content of the Instagram page, we created an artificial page. Surfing an artificial Instagram page does not reflect a real viewing situation where consumers search for content that matches their individual preferences. Second, we asked respondents in study 1 to pay equal attention to the media report and the Instagram site during the media multitasking situation. Such an instruction (i.e. a reminder not to forget one of the two tasks) does not correspond to a real viewing situation. Third, the high internal validity associated with our experimental approach comes at the cost of high external validity, since we could not control for external factors, such as other people, noises, or any kinds of stimuli that could distract the audience from the viewing experience. Although the level of distraction was measured and controlled for in all the analyses, the experimental setting prevents us from having full control of other disruptive factors.

This being so, the validation of our results through a real-world experiment would considerably increase their external validity, adding to the wider applicability of the results. Our research demonstrates the relevance of accounting for gender-related effects when designing advertising campaigns broadcasted in situations which require media multitasking. In this context, an exploration of the information processing differences between women and men during media multitasking in terms of brain activities through measuring electrodermal activity would validate our theoretical reasoning. Likewise, differences in attention toward the ad between women and men could be assessed by the use of eye-tracking technology. We relied only on favorable emotional appeals, however, advertising also often uses negative emotional appeals, such as fear. Likewise, humor and sexual appeals might also be processed differently by women and men. All these different appeals require future studies to better understand how women’s and men’s information-processing styles affect their impact on brand attitude during media multitasking. Moreover, future studies might explore how other contextual factors of the advertisement, such as prompting a consumer response, interact with gender and brand attitude formation.

Additionally, our study relied on a convenience sample, which limits the wider applicability of our results. We encourage future research to rely on quota samples to enhance the external validity of these findings. In this regard, it would be interesting to explore how groups other than those who identify as male and female, e.g. people who are non-binary, gender queer or intersex, respond to advertisements in media multitasking situations. Although these groups might represent a small proportion of a population, they represent important target groups which may respond to different contextual factors, potentially impacting on reactions to advertisements which have so far been under-researched. Further, other research suggests that an individual’s conception of self in terms of femininity vs masculinity may explain differences in emotional (image) vs rational (utilitarian) appeals (Chang 2016). Hence, a more inclusive approach to gender might be a fruitful avenue for future research.

Notes

It is now generally recognised that gender and biology vary beyond the traditional view of a binary identity assigned at birth based on external sex characteristics. However, for the purposes of data collection, and following an established body of research which uses a male/female binary as a major targeting variable in advertising (see, for example, Snyder and Debono 1985), the current study is restricted to those people who present on the traditional gender-binary divide and identify as female and male (synonymously, for the purposes of this paper, women and men).

Participants who indicated that they interrupted the study (n = 14) and did not pass the control question for the Instagram page in the media multitasking condition (n = 1) were excluded from the study. This reduced our sample from 156 to 141 participants (58% female, Mage = 31.83).

To provide further evidence for the robustness of our results and to rule out alternative mediators, we also test for possible indirect effects of the viewing situation on brand attitude via brand recognition and brand recall. As both the independent variable (viewing situation) and the mediator (brand recognition/brand recall) are categorical variables, we calculated the zMediation test to test for significant indirect effects. This test is comparable to z scores (see Iacobucci 2012) and is significant if it exceeds 1.96 for two-tailed tests with α = 0.05. We observe no indirect effect for brand recognition (ab = -0.58, zMediation = − 0.77) and brand recall (ab = -0.42, zMediation = − 1.04). Hence, brand recognition and recall do not serve as mediators between the viewing situation and brand attitude.

Only media multitaskers (i.e. participants who regularly read newspaper articles on their smartphone while watching TV) qualified for further analyses to assure high realism despite the artificial setting of the online experiment. Our final sample therefore consisted of 166 participants (40% female, Mage = 39.61).

References

Adaval R (2001) Sometimes it just feels right: The differential weighting of affect-consistent and affect-inconsistent product information. J Consum Res 28(1):1–17

Amaldoss W, He C (2010) Product variety, informative advertising, and price competition. J Mark Res 47(1):146–156

Angell R, Gorton M, Sauer J, Bottomley P, White J (2016) Don’t distract me when I’m media multitasking: toward a theory for raising advertising recall and recognition. J Advert 45(2):198–210

Ansary A, Nik Hashim NMH (2018) Brand image and equity: The mediating role of brand equity drivers and moderating effects of product type and word of mouth. RMS 12:969–1002

Bardhi F, Rohm AJ, Sultan F (2010) Tuning in and tuning out: Media multitasking among young consumers. J Consum Behav 9(4):316–332

Bellman S, Robinson JA, Wooley B, Varan D (2017) The effects of social TV on television advertising effectiveness. J Mark Commun 23(1):1–19

Beuckels E, Cauberghe V, Hudders L (2017) How media multitasking reduces advertising irritation: the moderating role of the Facebook wall. Comput Hum Behav 73:413–419

Brunel FF, Nelson MR (2000) Explaining gendered Responses to “help-self” and “help-others” charity ad appeals: The mediating role of world-views. J Advert 29(3):15–28

Chaiken S (1980) Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. J Pers Soc Psychol 39:752–766

Chaiken S, Ledgerwood A (2012) A theory of heuristic and systematic information processing. In: van Lange PAM (ed) Handbook of theories of social psychology, vol 1. SAGE, Los Angeles, pp 246–265

Chang Y (2016) Why do young people multitask with multiple media? Explicating the relationships among sensation seeking, needs, and media multitasking behavior. Media Psychol 20(4):685–703

Chen S, Chaiken S (1999) The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In: Chaiken S, Trope Y (eds) Dual-process theories in social psychology. The Guilford Press, pp 73–96

Chen YC, Shang RA, Kao CY (2009) The effects of information overload on consumers’ subjective state towards buying decision in the internet shopping environment. Electron Commer Res Appl 8:48–58

Chinchanachokchai S, Duff BR, Sar S (2015) The effect of multitasking on time perception, enjoyment, and ad evaluation. Comput Hum Behav 45:185–191

Chowdhury RM, Finn A, Olsen GD (2007) Investigating the simultaneous presentation of advertising and television programming. J Advert 36(3):85–96

Christov-Moore L, Simpson EA, Coudé G, Grigaityte K, Iacoboni M, Ferrari PF (2014) Empathy: gender effects in brain and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 46(4):604–627

Dahl DW, Sengupta J, Vohs KD (2009) Sex in Advertising: gender differences and the role of relationship commitment. J Consum Res 36(6):215–231

Darley WK, Smith RE (1993) Advertising claim objectivity: antecedents and effects. J Mark 57(4):100–113

Darley WK, Smith RE (2013) Gender differences in information processing strategies: an empirical test of the selectivity model in advertising response. J Advert 24(1):41–56

Dubé L, Morgan MS (1998) Capturing the dynamics of in-process consumption emotions and satisfaction in extended service transactions. Int J Res Mark 15(4):309–320

Duff BRL, Sar S (2015) Seeing the big picture: Multitasking and perceptual processing influences on ad recognition. J Advert 44(3):173–184

Duff BRL, Yoon G, Wang Z, Anghelcev G (2014) Doing it all: An exploratory study of predictors of media multitasking. J Interact Advert 14(1):11–23

Duff BRL, Segijn CM (2019) Advertising in a media multitasking era: Considerations and future directions. J Advert 48(1):27–37

Feiereisen S, Broderick AJ, Douglas SP (2009) The effect and moderation of gender identity congruity: Utilizing “real women” advertising images. Psychol Mark 26(9):813–843

Fisher RJ, Dubé L (2005) Gender differences in responses to emotional advertising: a social desirability perspective. J Consum Res 31(4):850–858

Forbes (2019) The LG V50 dual screen is perhaps the realistic foldable option for now. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bensin/2019/07/16/the-lg-v50-dual-screen-is-perhaps-the-realistic-foldable-option-for-now/#5ff2c7904826. Accessed 3 Dec 2019

Garaus M, Halkias G (2019) One color fits all: Product category color norms and (a)typical package colors. RMS 14:1077–1099

Garaus M, Wagner U, Bäck AM (2017) The effect of media multitasking on advertising message effectiveness. Psychol Mark 34(2):138–156

Gil de Zúñiga H, Garcia-Perdomo V, McGregor SC (2015) What is second screening? Exploring motivations of second screen use and its effect on online political participation. J Commun 65(5):793–815

Golden LL, Johnson KA (1983) The impact of sensory preference and thinking versus feeling appeals on advertising effectiveness. In Bagozzi RB, Tybout AM, Abor A (Eds) NA - Advances in consumer research, Vol 10, pp 203–208. Association for Consumer Research

Hampson E, van Anders S, Mullin L (2006) A female advantage in the recognition of emotional facial expressions: Test of an evolutionary hypothesis. Evol Hum Behav 27(6):401–416

Hartmann P, Apaolaza-Ibáñez V (2012) Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: the roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J Bus Res 65(9):1254–1263

Hayes AF (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guildford Press, New York

Holbrook MB (1978) Beyond attitude structure: Toward the informational determinants of attitude. J Mark Res 15(4):545–556