Abstract

The existing corporate governance literature has mostly focused on micro-level studies of executive compensation, with limited attention paid to influential macro-level factors such as institutions and institutional changes and their impacts on corporate governance and performance. The implementation of the new compensation policy that restricts CEO compensation ceiling in state-owned firms in China offers an ideal context for us to study how institutional changes and firms’ adoption of these changes can influence CEO turnover and firm performance. Our empirical analyses reveal that the positive impact of new compensation policy adoption on CEO turnover is stronger for CEOs with originally higher compensation. The impact of new compensation policy adoption on firm performance, however, is negative, and the negative impact is contingent upon a firm’s market share and tech intensity. Our research contributes to the literature on corporate governance by theorizing and empirically demonstrating the critical role that institutions play in corporate governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Executive compensation has received increasing attention from researchers, media, and the public as it is essential not only for enterprises but also for society (Murphy 1999). Prior literature on executive compensation has mostly focused on how organizations manage executive compensation packages at the micro-level of firms and executives. For instance, prior studies have discovered that executives’ characteristics (such as skills, tenure, experience, educational attainment, etc.) significantly influence their compensation (Attaway 2000; Banghøj et al. 2010; Cole and Mehran 2010; Hill and Phan 1991; O’Reilly et al. 1988). In addition to these objective attributes of executives, recent research from the managerial power perspective (Bebchuk et al., 2002; Bebchuk and Fried 2004) argues that executives use their power to influence boards of directors in seeking a favorable compensation package, while others conclude that it is not always the case (Buchholtz et al. 1998).

Executive compensation is one of the most critical aspects of corporate governance since executive compensation packages affect not only executives’ personal career decisions but also organizational decisions and outcomes. The corporate governance literature has long recognized the role of executive compensation packages as a measure of executives’ talent and effort, and often tied executive compensation to firm performance. Executive compensation has also been considered as an essential element of firms’ human capital strategy to attract and retain talent (Jensen and Murphy 1990a). This is because executives are more likely to withdraw from current organizations when their pay levels are lower than the labor market level. Besides, the executive pay level is a referent inside organizations. For instance, significant pay gaps within the internal hierarchy may cause subordinates to withdraw from organizations (Wade et al. 2006) when subordinates perceive the gap as inequity. Therefore, a significant pay gap inside organizations could be problematic.

While there is no doubt that these prior studies on executive compensation at the micro-level have made meaningful contributions to our knowledge on corporate governance, our understanding of executive compensation and its impacts is incomplete without taking into consideration the macro-level factors. To date, studies of executive compensation at the macro level are still limited, particularly when looking at legislative restriction to set executive compensation. The neglect is likely caused by literature on executive compensation and corporate governance being mainly focused on the context of developed economies. Institutions in these developed economies are much more developed than those in emerging economies and have remained mostly stable. The institutional transition in emerging economies not only raises questions on institutional impacts on executive compensation but also offers diverse and dynamic institutional environments for us to advance the research stream on corporate governance under various external contexts.

Our study investigates the influence of institutional change of pay practice on corporate governance, taking a new compensation policy as an exogenous source of valuation in executive compensation. The implementation of this new compensation policy offers an ideal study context for our study investigating the institutional impact on corporate governance, specifically on executive turnover and firm performance. We ask the following two research questions.

Firstly, how does the implementation of the new executive compensation policy affect CEO turnover? Over the past four decades, executives have received very high pay no matter how their firms perform in the market, and the pay gap between top executives and the average worker deepened significantly. To improve the efficiency of executive compensation setting during transition economy, the Chinese government imposed a new compensation policy for state-owned firms in 2015. With the new change of compensation policy, executives in state-owned firms received overall lower compensation than before. As for individual CEOs, monetary incentives are one of the most important factors determining one’s dedication to their organizations. As for organizations, pay incentive is probably the most important human capital strategy to retain talent (Coughlan and Schmidt 1985; Fong et al. 2010; Gayle et al. 2015). Organizations often take the market price as a reference point in managing executive compensation packages; that is, organizations refer to the labor market executive compensation and adjust it to generate their own compensation packages accordingly. Institutional change exerts a powerful force on both individuals and organizations regarding human resource allocation across firms; our study aims to understand the consequences of institutional change on the turnover of CEOs in state-owned firms.

Secondly, how does the implementation of the new executive compensation policy affect firm performance? As mentioned above, financial incentive plays an essential role in one’s decision on how much effort to put into their work. Pay reduction is likely to reduce the effort that one is willing to dedicate to the organization, leading to lower firm productivity. Meanwhile, the implementation of the new executive compensation policy may affect firm performance since executive compensation is linked to average employees’ wage to reduce the pay gap between top and bottom employees. Prior studies have revealed that a large pay gap negatively influences firm performance (Cowherd and Levine 1992; Crosby and Miren Gonzalez-Ital, 1984; Martin 1981). However, literature on the pay gap has not reached any consensus regarding its consequences due to the lack of empirical evidence. We draw insights from equity theory and relative deprivation theory to study the relationship between a firm’s adoption of the new compensation policy and its performance. In addition, we examine the contingent effects of CEO pay level, a firm’s market share, and high-tech intensity on the relationships examined in our research questions.

Our research contributes to the literature on corporate governance by examining the effect of institutional change on CEO turnover and firm performance. The findings are significant, yet varying. Extant literature has investigated executive pay from a micro-level (e.g. executives, organizations; Attaway 2000; Banghøj et al. 2010; Cole and Mehran 2010; O’Reilly et al. 1988). We extend the literature by studying the institutional change of executive compensation from a macro-level using data collected from China, an emerging economy. Furthermore, existing literature on executive compensation investigates executive pay mainly from the agency theory perspective (Jensen and Murphy 1990b; Hall and Liebman 1998; Tosi et al. 2000), whereas we carry out our investigation from the equity theory perspective. In a nutshell, institutional impacts on CEO turnover and firm performance enrich our understanding of the complex nature of institutional environments in affecting firms’ strategic activities and outcomes. Our analyses of the contingencies surrounding the relationships between policy change and corporate governance and consequences provide more in-depth knowledge to the existing literature on both institutions in emerging economies and corporate governance.

Our research also offers managerial implications to practitioners and policy-makers. In China, state-owned firms have been reformed since 1978; however, the governance of these firms is still in transition. The institutional change of pay practice in China seems to be effective based on empirical evidence found in our study. Firms’ responses to policy change can have significant influences on the outcomes of their human resource strategies as well as financial performance. For instance, firms may adjust an adequate strategy to attract and retain CEOs, since attracting and retaining CEOs is more difficult with the restriction on CEO compensation ceiling. In addition, firms may also pay attention to the pay gap between top executives and average employees when setting CEO compensation as a reference point of sublevels. The regulatory body should consider firms’ characteristics when setting restrictions on executive pay, since the effects of the new pay policy on firm performance are contingent on firm characteristics.

2 Pay policy reform in China

Over the past decades, high executive pay has increasingly attracted attention from the public, as well as scholars and politicians. For instance, in 1993, U.S. government approved a law proposal to constrain executive compensation (Rose and Wolfram 2000). Another example is the Israeli Treasury Committee of the Knesset passing a policy restricting executive compensation in 2016 (Abudy et al. 2017). Both policies were imposed in countries where the economies are developed. In China, similar efforts have also been made to restrict executive compensation in state-owned firms during transition economy. State-owned firmsFootnote 1 adopted a new pay policy in 2015, though it was launched in 2014. The new policy aimed to improve the corporate governance in state-owned firms, to restrict executive pay ceiling and to reduce the pay gap between executives and average employees in particular. An adequate executive pay package is a challenge for organizations as it is hard to determine how much value an executive would bring for shareholders. In other words, overpayment or underpayment is problematic for organizations (Wade et al. 2006). Overpayment is costly for organizations and underpayment may lead to withdrawal. In addition, the executive pay package is also an essential referent to determine the pay package of sublevels in organizations (Wade et al. 2006). The policy published by the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration CommissionFootnote 2 (SASAC) reduces the overall total compensation of executives and specifies three types of compensation included in the new executive compensation package: base salary, annual performance-based pay, and long-term three-year incentive. More precisely, the base salary of executives is tied to the wage of average workers and should be no more than twice the wage of average workers, aiming to manage the pay gap between top executives and ordinary workers; Annual performance-based pay is paid after annual assessment, which should be no more than twice the executives’ own base salary; Long-term three-year incentive is to motivate executives to devote their effort into their organizations and to reduce the chance of rewarding executives when the firm performance is poor, and this long-term three-year pay should be no more than 30 percent of the total compensation per year. Local SASAC and other related administrations are responsible for assessing executives’ performance. When the annual performance score is poor (marking criteria may vary across provinces), executives are not allowed to receive performance-based pay. Besides, performance-related pay increases only when the average worker’s salary also increases. The long-term three-year incentive is deferred pay, and it is cashed in a different proportion within three years after the long-term assessment.

Under the new compensation policy, the top executive’s wage decreases from 7.4 times an average employee’s wage to approximately 6.5 times (CNR NEWS 2016). Thus, it seems the policy goal of reducing the pay gap has been achieved. However, we know very little about the impact of this institutional change on firms, specifically CEO turnover and firm performance.

3 Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Equity theory (Adams 1963) suggests that, when evaluating whether one receives fair pay, s/he not only takes one’s own inputs and outputs into account, but also takes others’ pay as a reference point. When employees receive appropriate pay compared with others, they perceive fairness. Executives compare their pay levels with not only peers who are within their organizations, but also those from outside organizations. Therefore, to recruit and retain talent, boards of directors often take labor market rate as a reference point when they manage executive compensation (Ezzamel and Watson 1998; Fulmer 2009). The institutional change of pay practice reduces the total amount of CEO compensation and the pay gap between CEOs and average employees. From the equity theoretical perspective, CEOs are likely to re-evaluate their effort (input) dedicated to organizations due to the reduction in compensation. CEOs may be less motivated to contribute at the same level as before and may also perceive inequity when comparing with CEOs of outside organizations. When inequity occurs, action to restore equity will be taken by CEOs—for example, dedicating less effort to organizations (Adams 1965; Akerlof and Yellen 1990; Banker et al. 2016; Heyman 2005; Telly 1969) or withdrawing from organizations entirely (Fong et al. 2010; Greenberg 1990; Kale et al. 2014; Shen et al. 2010; Summers and Hendrix 1991; Williams et al. 2006). Additionally, the fairness perception of CEOs is complex and complicated; the monetary reward is often intercorrelated with CEOs’ perceptions of status, power, and job security (Adams 1965), which further magnifies the impact of pay cuts on CEOs’ contribution.

Furthermore, relative deprivation theory also addresses the importance of fair distribution in organizations. The relative deprivation theory suggests that individuals perceive deprivation if they learn that they have been paid less than they deserve when comparing their rewards to the rewards of referent groups (Cowherd and Levine 1992; Martin 1981, 1982). This theory is mainly used to deal with the comparison between classes within an organizational hierarchy (Cowherd and Levine 1992; Martin 1982). The institutional change of pay practice reduces the pay gap between top and bottom employees, so we assume that a state-owned firm’s adoption of the new compensation policy can also reshape the fairness perception of average employees due to the reduction in the pay gap, which consequently influences firm performance. Prior studies have discovered that a small pay gap between vertical classes inside a firm is beneficial to its financial performance (Cowherd and Levine 1992). A small pay gap within organizations contributes to improving the fairness perception of employees, which encourages employees to dedicate more effort to their organizations (Levine 1991). Next, considering the institutional change of pay practice as an exogenous source of executive compensation, we develop our hypotheses about the impact of CEO compensation on CEO turnover and firm performance below.

3.1 The effect of pay policy reform on CEO turnover

We argue that after adopting the new compensation policy, state-owned firms are more likely to experience CEO turnover than private-owned firms that are not affected by the new compensation policy. Shareholders employ adequate compensation packages to encourage their CEOs to manage firms in the interest of shareholders. Specifically, CEOs are rewarded when firm performance is good, and vice versa. In essence, firm performance reflects the effort (input) that CEOs contribute to firms and financial pay (outcomes) is one kind of outcomes that CEOs receive from firms. Thus, a compensation package, from the equity theory perspective, is a mean to align the interests of CEOs and shareholders (Fong 2004). CEOs perceive that they are being equitably paid when their contribution and pay are balanced.

Organizations manage the compensation package of CEOs based on the average pay rates in the labor market in their respective industry, which gives the probability that CEOs may be underpaid. CEOs may perceive underpayment if their performance is higher than the average performance in their respective industry (Aguinis et al. 2018), while their pay is around the average pay rate in the labor market. Empirical studies have solidified the link between underpaying and executive turnover. For instance, Shen et al. (2010) reported that executive pay negatively influences executive turnover using data of 313 large U.S. firms from 1988 to 1997. Prior research has also identified boundary conditions of the negative relationship between executive pay and turnover. For example, using U.S. listed firms’ data, Fong et al. (2010) found that the association between executive underpayment and executives’ turnover was stronger in owner-controlled firms. As the institutional change of pay practice in China reduced the total amount of CEO compensation, CEOs of state-owned firms that adopted the new policy were likely to perceive injustice or dissatisfaction. To restore fairness, these CEOs may seek alternative career opportunities outside organizations. In other words, turnover (exit) as a response to an organization (Hirschman 1970) can occur when CEOs perceive unfairness or dissatisfaction with their pay reductions in their organizations (Coviello et al. 2018; Sandvik et al. 2018). Therefore, with the reform practice of compensation in state-owned firms, we assume that CEO compensation restriction is more likely to lead CEOs to withdraw from current organizations. As such, we propose a positive relationship between new pay policy adoption and CEO turnover.

Hypothesis 1

Firms that adopted the new pay policy are more likely to experience CEO turnover.

We further argue that the impact of new compensation policy adoption is more impactful for CEOs with originally higher compensation levels. From the equity theory perspective, individuals suffering from a larger loss are likely to perceive a higher degree of injustice. Based on the new compensation policy, the total amount of compensation has been reduced proportionally, which results in a varied range of compensation reductions among CEOs. Consequently, perceptions of injustice resulting from diverse compensation reductions are varied among CEOs. To put it differently, CEOs who received originally higher compensation before the institutional change experienced more compensation reductions than those who received originally lower compensation before the institutional change. As a result, compensation reduction causes pay dissatisfaction (Bloom 1999; Cowherd and Levine 1992; Green and Heywood 2008; Martin 1982; Pfeffer and Langton 1993). Empirical studies have revealed that pay satisfaction negatively influences turnover intent (Currall et al. 2005; Lum et al. 1998; Shore 2004; Singh and Loncar 2010). Therefore, it is likely that larger compensation reduction (dissatisfaction) causes greater turnover intent. Therefore, we propose that:

Hypothesis 2

The impact of firms’ adoption of the new pay policy on CEO turnover is greater for CEOs with originally higher compensation.

3.2 The effect of pay policy reform on firm performance

We argue that firms adopting the new compensation policy experience lower financial performance than those that did not adopt the new policy. Prior theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that CEO compensation reduction leads to a decrease in organizational performance. As we have explained earlier based on the equity theory, compensation reduction is associated with the perception of inequity (Greenberg 1990), which results in CEOs’ withdrawal of efforts to their organizations. The same arguments have been made by agency theory scholars (Grabke-Rundell and Gomez-Mejia 2002; Kuo et al. 2014).

Empirical studies have detected that executive compensation exerts a positive impact on firm financial performance (Brunello et al. 2001; Duffhues and Kabir 2008; Jensen and Murphy 1990b; Leone et al. 2006) and identified contingent factors such as ownership structure (Brunello et al. 2001) and firm characteristics (e.g. profitability), and so forth. For instance, using a sample of 2213 CEOs’ data, Jensen and Murphy (1990b) confirmed the positive association between executive compensation and performance and reported that the elasticity of executive compensation to firm performance was about 0.1. Leone et al. (2006), based on panel data in a research period from 1992 until 2003, revealed that the elasticity of pay-performance differs under good news vs. bad news. Specifically, the elasticity of pay-performance is approximate 0.294 under a good news case and about 0.137 under a bad news case. They conclude that compensation is more sensitive under good news.

Building upon these studies and drawing from the equity theory, we argue that CEOs who experience compensation reduction are likely to perceive unfairness, and therefore restore the sense of equity by reducing inputs (effort) to their organizations. We consider the shrinking of effort as a type of “voice”, in the sense ofHirschman’s (1970).Footnote 3 This behavior consequently leads to a reduction in performance (Sandvik et al. 2018). As executives and CEOs are critical human resources of any organization and make strategically important decisions on behalf of their firms (Carpenter et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2019; Coombs and Gilley, 2005; Hambrick and Mason 1984; Zou et al. 2015), the withdrawal of contribution due to policy change will likely cause the decrease of their organizations’ performance. Thus, we propose the following.

Hypothesis 3

Firms that adopted the new pay policy experience lower firm performance.

We further argue for two moderating effects on the relationship proposed above (H3): market share and technology intensity.

As we have discussed above, CEOs assess whether they are equitably paid, based on the sum of job outcomes (Adams 1965). Job outcomes include monetary rewards and non-monetary benefits (e.g. status, job security) (Adams 1965). However, the economic-based outcome has been one of the most important drivers on CEO compensation literature to increase performance (Bonner and Sprinkle 2002; Jensen and Murphy 1990a; Stringer et al. 2011). Prior empirical studies have found that larger market share (Francis 1980; Marris 1964) or firm size can contribute to CEO compensation (Buck et al. 2008; Conyon 1997; Cosh 1975; Kaplan 1998; Lambert et al. 1991; Mcknight 1996; Sigler 2011; Sung and Swan 2009; Tosi et al. 2000; Zhou 2000) since the size of the market occupied by a firm and the size of the firm per se, to some degree correspond with the responsibilities on the CEO’s shoulders (Mcknight 1996; Sigler 2011) and with the skills or talent required by the firm (Conyon 1997). Thus, firms with larger market share often pay their CEOs higher. As discussed earlier, since the new compensation policy reduces CEO compensation proportionally, CEOs with originally higher compensation seem to experience larger pay reductions, which results in more dissatisfaction. Consequently, their withdrawal of contribution is greater, leading to a larger performance decline.

On the other hand, for CEOs from firms with smaller market share, their compensation reductions are limited. Therefore, when adopting the new compensation policy, they perceive smaller inequity than CEOs who work in firms with larger market share. As a result, their withdrawal of contribution is smaller, leading to performance declining slightly. We, therefore, expect that.

Hypothesis 4a

The negative impact of adopting the new pay policy on financial performance is greater for firms with larger market shares.

Equity theory suggests that employees evaluate whether they are being equitably paid based on the balance between themselves and their peers in similar organizations, in terms of the ratio of inputs to outcomes (Adams 1965). They also evaluate the balance between his/her own effort (input) and pay (outcome) (Katzell et al. 1976). Consistent with equity theory, the relative deprivation theory suggests that individuals perceive deprivation if they learn that they have been paid less than they deserve when comparing their rewards to the rewards of referent groups (Cowherd and Levine 1992; Martin 1981, 1982). When employees perceive inequity, for instance, when their effort is greater than pay or when the ratio of input to outcome is greater than that of their peers in similar organizations, negative behaviors such as dedicating less effort (Adams 1965; Banker et al. 2016; Telly 1969), employee theft (Greenberg 1990), withdrawal from organizations (Fong et al. 2010; Greenberg 1990; Kale et al. 2014; Shen et al. 2010; Summers and Hendrix 1991; Williams et al. 2006) and so forth, can occur.

We argue that the pay gap impact on average employees as a result of the new compensation policy adoption is more salient for firms with high technology intensity. The new compensation policy has reduced the pay gap by linking the base pay of executives to the wage of regular employees. That is, the base pay of executives is no more than two times the average wage of employees. The reduced pay gap can reshape feelings of fairness for regular employees, encouraging them to commit to organizations and to foster teamwork (Levine 1991). Empirical studies have discovered that organizations can benefit from a small pay gap (Bloom 1999; Conyon et al. 2001; Cowherd and Levine 1992; Faleye et al. 2010; Firth et al. 2015; Grund and Westergaard-Nielsen 2008; Henderson and Fredrickson 2001; Siegel and Hambrick 2005). This applies in particular to organizations that rely on collaboration effort (Bloom 1999). For instance, firms with high technology intensity (Gao and Zhang 2015; Lin et al. 2013; Siegel and Hambrick 2005). Siegel and Hambrick (2005), based on a high-technology firm data set, discovered that a large pay gap negatively influenced team collaboration and further influenced firm performance. In line with Siegel and Hambric’s finding, Gao and Zhang (2015) addressed that firms with high technology intensity tend to have a smaller pay gap in order to promote collaboration within teams and across units.

Therefore, for firms with higher technology intensity, their performances benefit more from the compressed pay gap since the reduced pay gap enhances the fairness perception of regular employees, leading to less reduction in performance. We therefore propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4b

The negative impact of adopting the new pay policy on firm performance is smaller for firms with higher levels of technology intensity.

Figure 1 offers an illustration of our hypotheses.

4 Methods

4.1 Sample

We collected our data from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database, a research-based database which has been widely used by many scholars (Chen et al. 2011; Xiang et al. 2020; Ye and Zhang 2011). We collected our samples from 2009 to 2017 to avoid other potential influences on our analyses (e.g. policy changes etc.). Our final sample consists of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private firms (non-SOEs) and sample firms and their distribution across years are reported in Table 1 below. The total observations for each analysis vary slightly due to the existence of valid data for the variables.

4.2 Variables

Dependent variables. Turnover is measured as a change of CEO, coded as 1 when there is a change in CEO position and 0 otherwise. In order to compare with prior findings, we use return on asset (ROA) to measure firm performance (Anderson and Reeb 2003; Nadkarni and Herrmann 2010).

Independent and moderating variables. The independent variable is new policy Adoption, which takes the value of 1 if a state-owned firm adopted the new pay policy in the corresponding years and 0 otherwise.

There are three moderating variables. CEO pay level indicates the degree of CEO pay in comparison to their peers in the same industry, denoted as variable Pay Level. This variable is calculated as the ratio of a CEO’s pay to the average CEO pay in the corresponding industry each year. Following Ryan and Wiggins (2002), Market Share is computed as the ratio of a firm's revenue to its industry’s total revenue in a specific year. Following Siegel and Hambric (2005), Technology Intensity is calculated as the R&D-to-Sales ratio. Since our data is firm-level data, we measure Technology Intensity using the ratio of a firm’s R&D spending to its revenue.

Control variables. We control the firm size, sales growth, and leverage due to their impact on firm performance reported in prior research (Nielsen and Nielsen 2013; Short et al. 2006). Firm Size is calculated as the natural logarithm of total assets and Sales Growth is calculated by the difference between the beginning and end of the fiscal year divided by the amount of the beginning of the year. Leverage is measured by the total liabilities divided by the total asset.

We control CEOs’ Age because prior scholars (Brickley 2003; DeFond and Park 1999; Goyal and Park 2002; Lausten 2002; Marsh and Mannari 1977) have discovered that CEOs who are near retirement age are more likely to withdraw from organizations than young CEOs. We control CEO Tenure as CEO turnover is affected by CEO tenure (Coates and Kraakman 2010; Goyal and Park 2002; Jenter and Lewellen 2014). Specifically, the probability of turnover is higher for CEOs who have shorter tenure, whereas the probability of leaving the office is likely lower for CEOs who have longer tenure. Education and Gender of CEOs are also considered as control variables as prior studies suggest that education is an important proxy of human capital (Barro and Lee 2013) and that education plays an essential role in CEOs’ selection process (Bhagat et al. 2010). Furthermore, scholars have found that Gender plays an essential role in turnover (Becker-Blease et al. 2010; Duffield et al. 2011; Lyness and Judiesch 2001; Stroh et al. 1996; Wilson et al. 2000). Some have concluded that females are more likely to experience turnover than males (Becker-Blease et al. 2010; Stroh et al. 1996; Wilson et al. 2000). This may be because females have family concerns, for instance, taking care of their young children (Duffield et al. 2011). Further, prior studies have revealed that CEO Duality exerts a significant impact on board control (Finkelstein and Hambrick 1989) and in turn impacts firm performance (Hillman and Dalziel 2003). We also control Board Size, computed as the total number of directors on board. The summary of all variables is presented in Table 2.

4.3 Analytical approach

Our first dependent variable, Turnover, is a binary variable. Therefore, we use the Probit regression model to estimate the impact of policy adoption on CEO turnover. In order to control year-related heterogeneity, we include year dummy variables in the regression model. Our second dependent variable is ROA; we use a fixed-effect model to estimate the policy adoption on firm performance (Magnan and St-Onge 2005). The fixed-effect model addresses the impact of unobserved but impactful features. Similarly, we include year dummy variables in our regression model to eliminate year-related heterogeneity.

5 Results

Tables 3 and 4 present the descriptive statistics of all variables and their correlations. The correlation coefficient of Turnover and Adoption is positively significant. While Adoption is negatively correlated to ROA. Correlation coefficients reveal that there is no collinearity issue in our analyses. Additionally, we also test the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each model and the VIF indicators are within acceptable limits, which are smaller than 10 (Wooldridge 2016).

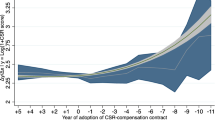

The Probit regression results with the dependent variable Turnover are summarized in Table 5. Model A shows the regression results for our base model including only control variables; Model B includes control variables and the independent variable, Adoption; the moderator Pay Level and its interaction term with Adoption enter our regression in Model C. Hypothesis 1 predicts that adoption of the new pay policy positively influences turnover. The coefficient on Adoption is not statistically significant (β = 0.012, p > 0.1), while the sign is positive as we have hypothesized. Hypothesis 2 predicts that the positive impact of new policy adoption on CEO turnover is stronger for CEOs who received higher pay. Model C shows that the interaction term of Adoption and Pay Level is positive (β = 0.173, p < 0.05). This offers empirical evidence that the impact of new pay policy adoption on CEO turnover is stronger for those with higher pay as hypothesized. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported. Figure 2 displays the predicted marginal effects at different pay levels (pay level = 1/2/3/4) and policy adoption (0 and 1). The results show that the probability of CEO turnover (= 1) is higher for firms that adopted the new pay policy when the pay level is greater than 1. This reflects that when CEO pay is higher than the average CEO pay in the corresponding industry, adoption of the new pay policy increases the probability of turnover even more.

The fixed-effects analyses with the dependent variable ROA are summarized in Table 6. Similar to in Table 5, we include only control variables in Model A, add the independent variable, Adoption, in Model B, and include the two moderating variables and their interaction terms – Market Share and Technology Intensity – in Models C and D respectively.

Hypothesis 3 posits that the adoption of the new pay policy negatively influences firm financial performance. Model B in Table 6 provides strong evidence supporting Hypothesis 3 with the coefficient on Adoption being negative and statistically significant (β = − 0.005, p < 0.05).

Model C estimates the moderating effect of Market Share on the relationship between new pay policy Adoption and ROA. The results suggest that the negative impact of Adoption on ROA gets stronger with Market Share increases (β = − 0.078, p < 0.05), providing strong support for Hypothesis 4a. Figure 3 offers a visual illustration of the results in Model C. The y-axis presents the predicted marginal effects of adoption on ROA; the x-axis presents Market Share. We observe a significant moderating effect of Market Share; the statistical significance level is indicated by the dotted 95 percent confidence interval lines.

Model D manifests that the interaction term of Adoption and Technology Intensity is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.255, p < 0.05), which provides strong evidence for Hypothesis 4b, predicting that the negative impact of Adoption on ROA is smaller for firms with high technology intensity. We provide Fig. 4 to display the moderating effect of Technology Intensity on the relationship between Adoption and ROA. The y-axis presents the predicted marginal effect of adoption on ROA while the x-axis presents technology intensity. When technology intensity is greater than about 0.05, new pay policy adoption contributes more to ROA with technology intensity increase (significance level indicated by the dotted 95 percent confidence interval lines).

5.1 Robustness test

With the intention of testing the robustness of the empirical results, we implement the Difference-in-Difference (DID) approach to re-estimate the impact of Adoption on Turnover and ROA. The Difference-in-DifferenceFootnote 4 approach can reduce the endogeneity resulted from sample bias and omitted variables. We define binary variable Treat, encoded as 1 for firms that adopted the new pay policy and 0 otherwise. Time indicator variable, Post, 1 presenting years that adopted the new pay policy and 0 otherwise.

Model A and Model B in Table 7 refer to the estimated regression results of Hypotheses 1 and 2. As expected, the results (β = 0.008, p > 0.1; β = 0.294, p < 0.05) confirm the findings reported in Table 5. Models C, D and E in Table 7 re-estimate H3, H4a and H4b, and confirm the findings in Table 6 (β = − 0.005, p < 0.05; β = − 0.100, p < 0.05; β = 0.296, p < 0.05).

6 Discussion

In the current study, we examine the impact of institutional change on corporate governance and firms in the transition economy of China. We specifically focus on the impact of new compensation policy adoption on CEO turnover and firm financial performance. Our empirical results suggest that the adoption of the new compensation policy has a stronger positive impact on turnover for CEOs who have originally higher compensation. Besides, our results reveal that the adoption of the compensation policy leads to a significant decrease in firm performance, which in turn is greater for firms with larger market shares. However, the adoption of the compensation policy can contribute to firm performance for firms with higher technology intensity.

6.1 Theoretical and managerial implications

Our study makes two primary contributions to the existing literature on corporate governance. Firstly, the literature on executive compensation has mainly focused on the factors that impacted executive compensation at the micro-level of organizations and executives (Attaway 2000; Banghøj et al. 2010; Cole and Mehran 2010; O’Reilly et al. 1988). Taking advantage of the institutional change of pay practice in China, we study the effect of institutional change on CEO compensation, extending factors that impacted CEO compensation to a macro level. Our results highlight the critical role of institutions in executive compensation setting, particularly in transition economy where the corporate governance is poor.

Secondly, prior studies mainly investigate executive compensation from the agency theory perspective (Jensen and Murphy 1990b; Hall and Liebman 1998; Tosi et al. 2000) and managerial approach (Bebchuk et al. 2002; Bebchuk and Fried 2004). This study contributes to executive compensation literature by exploring the impact of institutional changes on CEO turnover and firm performance from the equity theory perspective. During the period of economic transition in China, state-owned enterprises have adopted a performance-related pay regime that dominated corporate governance in western countries. However, the growing pay gap rising from performance-related pay has received increasing attention from the public. The public concerns about fairness when it comes to executive pay-performance (Walsh 2008), in particular in Asia where society stresses great social fairness (Sun et al. 2010). The institutional change of pay practice has reduced both executive compensation and the pay gap between executives and average employees. Our results are consistent with the prediction of equity theory. Specifically, compensation plays a critical role in judging whether one is being equally treated in organizations (Guo, 2011). Our results reveal that higher-paid CEOs are more likely to leave because of the restrictions on their compensation, which is consistent with prior finding conducted by Kleymenova and Tuna (2021). This is because greater compensation reduction results in the perception of unfairness. The reform practice of compensation brings challenge in retaining top executives. As Victor Wang, a Hong Kong-based analyst at Credit Suisse Group AG, pointed out “The restriction will make it hard to retain high-quality talent in state-owned banks”. Another consequence of pay reduction is withdrawal effort, which is supported by our results—institutional change of pay practice leading to decrease in firm performance. This is consistent with the study conducted by Dittmann et al. (2011). Furthermore, our study offers empirical evidence supporting that capping CEO compensation does have an impact on equity and fairness concerned by voters (voters refer to stockholders with voting rights) as mentioned in Zhang’s (2012). Under the institutional change of compensation, the pay gap between CEOs and regular employees has been reduced, which can reshape employees’ perception of fairness. The reduced pay gap further affects firm performance, as a small pay gap can contribute to cohesiveness (Levine 1991). This study therefore reveals the complex nature of executive compensation setting. That is, executive compensation setting should concern not only economic growth but also fairness (Walsh 2008; Yang and Kakabadse 2013).

Our study also offers policy and managerial implications. The institutional change of pay practice reduces executive compensation but it also has unintended consequences. That is, the institutional change reduces executive compensation, while the reduction in compensation leads to decrease in firm performance. In other words, while pay reduction saves organizational cost, it also leads to executives losing motivation. Therefore, the board of directors may adjust adequate human capital strategies to recruit and retain talent, further improving firm performance. Another practical implication is that policy-makers may concern the pay gap between vertical classes within organizations. Allocation of pay influences both upper and bottom employees, as average employees usually consider the upper class as referent pay groups (Banker et al. 2016; Cowherd and Levine 1992). Policy-makers may also pay attention to the characteristics of firms when setting executive pay as a reference point for sublevels. As evidenced in our study, for organizations that rely on collaborative effort, firm performance benefits from a smaller pay gap. Our study reveals that the adoption leads to an unintended consequence, firms with larger market shares experiencing a decrease in financial performance. This suggests the regulatory body should pay extra attention to firms’ characteristics when setting restrictions on executive compensation. To conclude, our study offers important implications for the reform practice of executive compensation in China. That is, this study offers motivation in restricting executive compensation. However, in order to reduce the unintended consequence of capping executive compensation, the regulatory body may improve the reform practice of executive compensation.

6.2 Limitations and future research avenues

There are several limitations in this study that are worth noting and pointing out for future research opportunities. Firstly, we investigate the institutional impact on executive compensation in a transition economy context, using data collected in China. However, results could vary in other economic contexts. Future studies, therefore, can explore the institutional impact in western countries where the economy is relatively stable. Secondly, in this study, due to the availability of data, CEO total compensation mainly refers to explicit pay. Future studies can explore whether the institutional change of pay has an impact on implicit pay and whether it further affects CEOs’ behavior and firm performance.

The new compensation policy was imposed on state-owned enterprises by the government and it has restricted the executive pay ceiling in state-owned firms. We fail to find evidence supporting our first Hypothesis predicting that the adoption of the new pay policy leads to CEO turnover. This can perhaps be explained from the stewardship theory perspective (Donaldson and Davis 1991). Compared with CEOs in private firms, CEOs in state-owned firms are usually appointed by the government (Cao et al. 2019). CEOs may perceive the appointment as recognition by their organization, which diminishes the effect of compensation as a motivator. In other words, CEOs in state-owned firms may consider recognition (intrinsic motivation) as a more important motivator than monetary incentives. However, we find the adoption of the new policy leading to withdrawal for those CEOs with higher compensation levels. Therefore, investigating how intrinsic motivators (e.g. recognition, etc.) and monetary incentives interact in driving one’s behavior may be a fruitful future study area, in the context of Chinese state-owned firms in particular. Future study may investigate how the implementation impacts board composition in state-owned firms. Specifically, the proportion of outside directors may change in order to execute the new pay policy effectively. Future research may also explore the effect of the institutional change on the executive labor market in China. More precisely, the adoption of the new pay policy leads to CEOs with originally higher compensation levels withdrawing from their current position as evidenced in our study, which may be impactful for private firms. CEOs withdrawing from state-owned firms may increase the competition in the executive labor market in China. This change could affect the executive selection in private-owned firms, as well as the human capital strategies related to pay.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Firm type is categorized by the type of controlling shareholder: state-owned firms and private-owned firms.

SASAC is a government unit that manages state-owned enterprises in China. The new compensation policy was imposed by the government on state-owned enterprises. And private-owned firms are not affected by this policy.

In Hirschman’s (1970), voice is defined as “any attempt at all to change, rather than to escape from, an objectionable state of affairs, […] through various types of actions and protests (page 30).”.

We also test the parallel trend assumption before we implement DID method, and the results suggest that the parallel trend assumption is satisfied.

References

Abudy M, Amiram D, Rozenbaum O, Shust E (2017) Do executive compensation contracts maximize firm value? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Columbia Business School Research Paper No. 17, 69.

Adams JS (1963) Towards an understanding of inequity. J Abnormal Soc Psychol 67(5):422

Adams JS (1965) Inequity in social exchange. Elsevier

Aguinis H, Martin GP, Gomez-Mejia LR, O’Boyle Jr EH, Joo H (2018) The two sides of CEO pay injustice: a power law conceptualization of CEO over and underpayment. Manage Res J Iberoam Acad Manage 16(1):3–30

Akerlof GA, Yellen JL (1990) The fair wage-effort hypothesis and unemployment. Q J Econ 105(2):255–283

Anderson RC, Reeb DM (2003) Founding-family ownership and firm performance: evidence from the S&P 500. J Financ 58(3):1301–1328

Attaway MC (2000) A study of the relationship between company performance and CEO compensation. Am Bus Rev 18(1):77

Banghøj J, Gabrielsen G, Petersen C, Plenborg T (2010) Determinants of executive compensation in privately held firms. Account Finance 50(3):481–510

Banker RD, Danlu Bu, Mehta MN (2016) Pay gap and performance in China. Abacus 52(3):501–531

Barro RJ, Lee J-W (2013) A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. J Dev Econ 104:184–198

Bebchuk L, Fried J (2004) Pay without Performance. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Bebchuk LA, Fried JM, Walker DI (2002) Managerial power and rent extraction in the design of executive compensation. Univ Chicago Law Rev 69:751–846

Becker-Blease JR, Elkinawy S, Stater M (2010) The impact of gender on voluntary and involuntary executive departure. Econ Inq 48(4):1102–1118

Bhagat S, Bolton BJ, Subramanian A (2010) “CEO Education, CEO Turnover, and Firm Performance.” working paper. University of Colorado Boulder, University of New Hampshire, & Georgia State University.

Bloom M (1999) The performance effects of pay dispersion on individuals and organizations. Acad Manag J 42(1):25–40

Bonner SE, Sprinkle GB (2002) The effects of monetary incentives on effort and task performance: theories, evidence, and a framework for research. Account Organ Soc 27(4/5):303–345

Brickley JA (2003) Empirical research on CEO turnover and firm-performance: a discussion. J Account Econ 36(1/3):227–233

Brunello G, Graziano C, Parigi BM (2001) Executive compensation and firm performance in Italy. Int J Ind Org 19(1–2):133–161

Buchholtz AK, Young MN, Powell GN (1998) Are board members pawns or watchdogs? The link between CEO pay and firm performance. Group Org Manag 23(1):6–26

Buck T, Liu X, Skovoroda R (2008) Top executive pay and firm performance in China. J Int Bus Stud 39(5):833–850

Cao X, Lemmon M, Pan X, Qian M, Tian G (2019) Political promotion, CEO incentives, and the relationship between pay and performance. Manage Sci 65(7):2947–2965

Carpenter MA, Geletkanycz MA, Sanders WG (2004) Upper echelons research revisited: antecedents, elements, and consequences of top management team composition. J Manag 30(6):749–778

Chen S, Sun Z, Tang S, Wu D (2011) Government intervention and investment efficiency: evidence from China. J Corp Finan 17(2):259–271

Chen WT, Zhou GS, Zhu XK (2019) CEO tenure and corporate social responsibility performance. J Bus Res 95:292–302

Coates JC, Kraakman R (2010) “CEO Tenure, Performance and Turnover in S&P 500 Companies,” unpublished working paper, Harvard Law School, Boston

Cole R, Mehran H (2010) “What Can We Learn from Privately Held Firms about Executive Compensation?” working paper. New York: Federal Reserve Board of New York.

Conyon MJ (1997) Corporate governance and executive compensation. Int J Ind Organ 15(4):493–509

Conyon MJ, Peck SI, Sadler GV (2001) Corporate tournaments and executive compensation: evidence from the UK. Strategic Manag J 22(8):805–815

Coombs JE, Gilley KM (2005) Stakeholder management as a predictor of CEO compensation: main effects and interactions with financial performance. Strateg Manag J 26(9):827–840

Cosh A (1975) The remuneration of chief executives in the United Kingdom. Econ J 85(337):75–94

Coughlan AT, Schmidt RM (1985) Executive compensation, management turnover, and firm performance: an empirical investigation. J Account Econ 7(1–3):43–66

Coviello D, Deserranno E, Persico N (2018) Exit, voice, and loyalty after a pay cut.

Cowherd DM, Levine DI (1992) Product quality and pay equity between lower-level employees and top management: an investigation of distributive justice theory. Adm Sci Q 37(2):302–320

Crosby F, Miren Gonzalez-Ital A (1984) Relative deprivation and equity theories. In Robert Folger (eds), The Sense of Injustice: Social psychological perspective, pp 141–166. New York Plenum

Currall SC, Towler AJ, Judge TA, Kohn L (2005) Pay satisfaction and organizational outcome. Pers Psychol 58(3):613–640

DeFond ML, Park CW (1999) The effect of competition on CEO turnover. J Account Econ 27(1):35–56

Dittmann I, Maug E, Zhang D (2011) Restricting CEO pay. J Corp Finan 17(4):1200–1220

Donaldson L, Davis JH (1991) Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Aust J Manag 16(1):49–64

Duffhues P, Kabir R (2008) Is the pay-performance relationship always positive?: Evidence from the Netherlands. J Multinatl Financ Manag 18(1):45–60

Duffield C, Roche M, Blay N, Thoms D, Stasa H (2011) The consequences of executive turnover. J Res Nurs 16(6):503–514

Ezzamel M, Watson R (1998) Market comparison and the bidding-up of executive cash compensation: evidence from the United Kingdom. Acad Manag J 41(2):221–231

Faleye O, Reis E, Venkateswaran A (2010) “The Effect of Executive-Employee Pay Disparity on Labor Productivity.” Paper presented at European Financial Management Association Annual Meeting, Aarhus.

Finkelstein S, Hambrick D (1989) Chief executive compensation: a study of the intersection of markets and political process. Strateg Manag J 10(2):121–134

Firth M, Leung TY, Rui OM, Na C (2015) Relative pay and its effects on firm efficiency in a transitional economy. J Econ Behav Organ 110:59–77

Fong EA, Misangyi VF, Tosi HL (2010) The effect of CEO pay deviations on CEO withdrawal, firm size, and firm profits. Strateg Manag J 31(6):629–651

Fong, Eric A. (2004) Chief Executive officer (CEO) Responses to CEO Compensation Equity. Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida.

Francis A (1980) Company objectives, managerial motivations and the behavior of large firms: an empirical test of the theory of managerial’ capitalism. Camb J Econ 4(4):349–361

Fulmer IS (2009) The elephant in the room: labor market influences on CEO compensation. Pers Psychol 62(4):659–695

Gao Z, Zhang C-Z (2015) “Empirical Study on the Relationship between Executive-Employee Pay Gap and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Technology Intensity.” Paper presented at International Conference on Education, Management and Information Technology. Atlantis Press.

Gayle G-L, Golan L, Miller RA (2015) Promotion, turnover, and compensation in the executive labor market. Econometrica 83(6):2293–2369

Goyal VK, Park CW (2002) Board leadership structure and CEO turnover. J Corp Finan 8(1):49–66

Grabke-Rundell A, Gomez-Mejia LR (2002) Power as a determinant of executive compensation. Hum Resour Manag Rev 12(1):3–23

Green C, Heywood JS (2008) Does performance pay increase job satisfaction? Economica 75(300):710–728

Greenberg J (1990) Employee theft as a reaction to underpayment inequity: the hidden cost of pay cuts. J Appl Psychol 75(5):561

Grund C, Westergaard-Nielsen N (2008) The dispersion of employees’ Wage increases and firm performance. ILR Rev 61(4):485–501

Guo Z (2011) Can the executive pay limits restrict compensations: an explanation by principal-agent model based on equity theory. J Guangxi Univ Finance and Econ

Hall BJ, Liebman JB (1998) Are CEOs really paid like bureaucrats? Q J Econ 113(3):653–691

Hambrick DC, Mason PA (1984) Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad Manag Rev 9(2):193–206

Henderson AD, Fredrickson JW (2001) Top management team coordination needs and the CEO pay gap: a competitive test of economic and behavioral views. Acad Manag J 44(1):96–117

Heyman F (2005) Pay inequality and firm performance: evidence from matched employer-employee data. Appl Econ 37(11):1313–1327

Hill CWL, Phan P (1991) CEO tenure as a determinant of CEO Pay. Acad Manag J 34(3):707–717

Hillman AJ, Dalziel T (2003) Boards of directors and firm performance: integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Acad Manag Rev 28(3):383–396

Hirschman AO (1970) Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states, vol 25. Harvard University Press.

Jensen MC, Murphy KJ (1990a) CEO incentives—it’s not how much you pay, but How. J Appl Corp Financ 3(3):36–49

Jensen MC, Murphy KJ (1990b) Performance pay and top-management incentives. J Polit Econ 98(2):225–264

Jenter D, Lewellen K (2014) “Performance-Induced CEO Turnover.” Stanford University.

Jr Ryan HE, Wiggins RA III (2002) The interactions between R&D investment decisions and compensation policy. Financ Manage 31:5–29

Kale JR, Reis E, Venkateswaran A (2014) Pay inequalities and managerial turnover. J Empir Financ 27:21–39

Kaplan SN (1998) Top executive incentives in Germany, Japan and the USA: a comparison. Execut Compen Shareholder Value Theory Evidence 4(3):3–12

Katzell RA, Yankelovich D, Fein M, Ornati OA, Nasj A (1976) Pay vs work motivation and job satisfaction. Compen Rev 8(1):54–66

Kleymenova A, Tuna İ (2021) Regulation of compensation and systemic risk: evidence from the UK. J Account Res 59(3):1123–1175

Kuo H-C, Lin D, Lien D, Wang L-H, Yeh L-J (2014) Is there an inverse u-shaped relationship between pay and performance? The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 28:347–357

Lambert RA, Larcker DF, Weigelt K (1991) How sensitive is executive compensation to organizational size? Strateg Manag J 12(5):395–402

Lausten M (2002) CEO turnover, firm performance and corporate governance: empirical evidence on Danish firms. Int J Ind Organ 20(3):391–414

Leone AJ, Joanna Shuang Wu, Zimmerman JL (2006) Asymmetric sensitivity of CEO cash compensation to stock returns. J Account Econ 42(1–2):167–192

Levine D (1991) Cohesiveness, productivity, and wage dispersion. J Econ Behav Organ 15(2):237–255

Lin Y-F, Yeh YMC, Shih Y-T (2013) Tournament theory’s perspective of executive pay gaps. J Bus Res 66(5):585–592

Lum L, Kervin J, Clark K, Reid F, Sirola W (1998) Explaining nursing turnover intent: job satisfaction, pay satisfaction, or organizational commitment? J Org Behav 19(3):305–320

Lyness KS, Judiesch MK (2001) Are female managers quitters? The relationships of gender, promotions, and family leaves of absence to voluntary turnover. J Appl Psychol 86(6):1167

Magnan M, St-Onge S (2005) The impact of profit sharing on the performance of financial services firms. J Manage Stud 42(4):761–791

Marris R (1964) The economic theory of managerial capitalism. Free Press, New York

Marsh RM, Mannari H (1977) Organizational commitment and turnover: a prediction study. Adm Sci Q 22(1):57–75

Martin J (1981) Relative deprivation: a theory of distributive justice for an era of shrinking resources. In: Cummings LL, Staw BM (eds) Research in organizational behavior, vol 3. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp 53–108

Martin J (1982) The fairness of earnings differentials: an experimental study of the perceptions of blue-collar workers. J Hum Resour 17(1):110–122

McKnight PJ (1996) An explanation of top executive pay: a UK study. Br J Ind Relat 34(4):557–566

Murphy KJ (1999) Executive compensation. Handbook of Labor Economics 3:2485–2563

Nadkarni S, Herrmann POL (2010) CEO personality, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: the case of the Indian business process outsourcing industry. Acad Manag J 5(5):1050–1073

Nielsen BB, Nielsen S (2013) Top management team nationality diversity and firm performance: a multilevel study. Strateg Manag J 34(3):373–382

O’Reilly III, Charles A, Main BG, Crystal GS (1988) CEO compensation as tournament and social comparison: a tale of two theories. Adm Sci Q 33(2):257–274

Pfeffer J, Langton N (1993) The effect of wage dispersion on satisfaction, productivity, and working collaboratively: evidence from college and university faculty. Adm Sci Q 38(3):382–407

Rose NL, Wolfram C (2000) Has the" million-dollar cap" affected CEO pay? Am Econ Rev 90(2):197–202

Sandvik J, Saouma R, Seegert N, Stanton C (2018) Analyzing the aftermath of a compensation reduction. Natl Bureau Econ Res

Shen W, Gentry RJ, Tosi Jr HL (2010) The impact of pay on CEO turnover: a test of two perspectives. J Bus Res 63(7):729–734

Shore TH (2004) Equity sensitivity theory: do we all want more than we deserve? J Manag Psychol 19(7):722–728

Short JC, Ketchen Jr DJ, Bennett N, du Toit M (2006) An examination of firm, industry, and time effects on performance using random coefficients modeling. Organ Res Methods 9(3):259–284

Siegel PA, Hambrick DC (2005) Pay disparities within top management groups: evidence of harmful effects on performance of high-technology firms. Organ Sci 16(3):259–274

Sigler KJ (2011) CEO compensation and company performance. Bus Econ J 31(1):1–8

Singh P, Loncar N (2010) Pay satisfaction, job satisfaction and turnover intent. Relat Ind 65(3):470–490

Stringer C, Didham J, Theivananthampillai P (2011) Motivation, pay satisfaction, and job satisfaction of front-line employees. Qual Res Account Manag 8(2):161–179

Stroh LK, Brett JM, Reilly AH (1996) Family structure, glass ceiling, and traditional explanations for the differential rate of turnover of female and male managers. J Vocat Behav 49(1):99–118

Summers TP, Hendrix WH (1991) Modelling the role of pay equity perception: a field study. J Occup Psychol 64(2):145–157

Sun SL, Zhao X, Yang H (2010) Executive compensation in Asia: a critical review and outlook. Asia Pacific J Manag 27(4):775–802

Sung J, Swan PL (2009) Executive pay, talent and firm size. Talent and Firm Size. Working paper

Telly CS (1969) Inequity and its relationship to turnover among hourly workers in the major production shops of the Boeing company. Academy of Management Proceedings. pp 119–124

Tosi HL, Werner S, Katz JP, Gomez-Mejia LR (2000) How much does performance matter? A meta-analysis of CEO pay studies. J Manag 26:301–339

Wade JB, O’Reilly CA, Pollock TG (2006) Overpaid CEOs and underpaid managers: fairness and executive compensation. Organ Sci 17(5):527–544

Walsh JP (2008) CEO compensation and the responsibilities of the business scholar to society. Acad Manag Perspect 22(2):26–33

Williams ML, McDaniel MA, Nguyen NT (2006) A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of pay level satisfaction. J Appl Psychol 91(2):392

Wilson CN, Stranahan H, Mitrick JM (2000) Organizational characteristics associated with hospital CEO turnover/practitioner application. J Healthc Manag 45(6):395

Wooldridge JM (2016) Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. Nelson Education.

Xiang C, Chen F, Jones P, Xia S (2020) The effect of institutional investors’ distraction on firms’ corporate social responsibility engagement: Evidence from China. Review of Managerial Science, pp 1–37

Yang JH, Kakabadse NK (2013) How Chinese styled executive remuneration works: evidence from Chinese red-chips. In How to Make Boards Work. Springer, pp 75–94

Ye K, Zhang R (2011) Do lenders value corporate social responsibility? Evidence from China. J Bus Ethics 104(2):197–206

Zhang D (2012) Essays in executive compensation.

Zhou X (2000) CEO pay, firm size, and corporate performance: evidence from Canada. Can J Econ 33(1):213–251

Zou HL, Zeng SX, Lin H, Xie XM (2015) Top executives’ compensation, industrial competition, and corporate environmental performance: evidence from China. Manag Decis 53:2036–2059

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, C., Li, D. & Salmador, M.P. Institutional change of compensation policy and its impact on CEO turnover and firm performance. Rev Manag Sci 16, 2527–2552 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00507-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00507-3