Abstract

The increasing misalignment between the technological and economic domains in today’s digitalized global economy puts managers under constant pressure to redesign firms’ business models. Business model innovation has thus become a critical managerial challenge to develop and sustain competitive advantages. Building on the dynamic managerial capabilities perspective, we argue that managers are at the heart of strategic change through business model innovation. We hypothesize that decision-making regarding business model innovation is the outcome of how managers cognitively process information. We further reason that while managerial human capital and social capital reinforce each other, they also promote managers’ ability to consciously evaluate options for business model innovation. Our empirical study builds on a sample of firms operating primarily within the Industry 4.0 sector. The results significantly confirm managerial human and social capital as two crucial antecedents to cognitive business model innovation. Contrary to the literature, the data set does not show a significant positive relationship between managerial human and social capital. Our main contributions to the literature are twofold; from a methodological perspective, we are one of the first to construct a multidimensional measurement of dynamic managerial capabilities, while from a theoretical and practical perspective, our findings further underline the relevance of dynamic managerial capabilities for business model innovation. Finally, we discuss theoretical and practical implications and propose future avenues for research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As a major driver of business model innovation, digital transformation pressures managers to undertake strategic change (Kraus et al. 2018; Acciarini et al. 2020). This 21st-century megatrend causes the “increasing implementation of digital technologies and the transformation of conventional processes into digital ones” (Bouncken et al. 2021, p. 2). Digitalization, therefore, fundamentally questions current competitive advantages by changing the rules of competition (Acciarini et al. 2020; Penttilä et al. 2020). In light of these developments, a firm’s long-term success largely depends on its managerial ability to align the existing mechanisms of value proposition, value creation, and value capture—that is, the business model—with the ever-changing demands of the environment (Clauss et al. 2019a). To survive in the digital economy, firms can no longer solely rely on innovating their products, services, or processes. The business model has become a central avenue for innovation (Purkayastha and Sharma 2016; Clauss et al. 2019b), and business model innovation has consequently turned into one of the most daunting managerial tasks (Eppler et al. 2011).

We adopt the dynamic managerial capabilities perspective to analyze the decision-making processes related to business model innovation. Dynamic managerial capabilities highlight the managerial role within strategic decision-making. Managers possess the capabilities—namely, human capital, social capital, and cognition—that are required to “build, integrate, and reconfigure organizational resources and competences” (Adner and Helfat 2003, p. 1012). As managerial capabilities shape organizational decision-making, the strength of firm-intrinsic dynamic managerial capabilities is a central driver of business model innovation (Teece 2018).

Despite their centrality to sustained competitive advantage through innovation (Kaplan and Tripsas 2008) and business model design (Teece 2018), there is still limited knowledge on how managerial capabilities affect organizational change (Felin et al. 2012). The few existing studies focus on the drivers of dynamic managerial capabilities individually (e.g., Åberg and Torchia 2020) or measure psychological characteristics with observable proxies (e.g., Holzmayer and Schmidt 2020). Hence, our first research goal relates to the holistic operationalization of dynamic managerial capabilities:

How can the concept of dynamic managerial capabilities be operationalized from a multidimensional perspective?

Subsequently, we adopt the dynamic managerial capabilities perspective to examine the effects of managerial characteristics on strategic decision-making related to business model innovation. Managers possess the capability to orchestrate the firm’s asset portfolio (i.e., resources and capabilities). The unique composition of the asset portfolio, in turn, determines the pathways for strategic change and ultimately shapes company performance (Helfat and Martin 2015a). Efficient management must consequently organize and align all operative and strategic activities of the firm through the business model (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010). Due to the high level of dynamism, competition, and uncertainty, the current digital business paradigm causes an increasing discrepancy between company strategy and processes (Al-Debei et al. 2008). As dynamic managerial capabilities determine the managerial ability to configure, develop, and deploy the firm’s asset portfolio (Adner and Helfat 2003), they have become a critical success factor for target-oriented business model innovation. This argumentation leads to our second research question:

How do the three dimensions of dynamic managerial capabilities interact in the context of business model innovation?

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we first outline the general concept of dynamic managerial capabilities and its three underlying managerial capabilities. Subsequently, we describe the business model and adopt a processual view of business model innovation. We derive the research model, which analyzes the interrelationships between dynamic managerial capabilities, in Sect. 3. Section 4 outlines our research methodology. We present the empirical results in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6, we discuss theoretical and practical implications. We conclude with an assessment of the limitations and the outlook for future research.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Dynamic managerial capabilities

2.1.1 Moving beyond the collective level of analysis

Dynamic managerial capabilities relate to the specific subset of managers’ dynamic capabilities (Adner and Helfat 2003). From this perspective, a company’s management comprises a heterogeneous group of decision-makers, which decisively shapes outcomes through identifiable strategic choices (Beck and Wiersema 2013). The driving forces behind both dynamic capabilities and dynamic managerial capabilities are routines (i.e., practiced and patterned behaviors). The former, however, does not necessarily involve managerial intentionality, while the latter posits that intent is the driving force behind firm-specific routines (Martin 2011). Consequently, dynamic managerial capabilities exist if executive action reliably causes the intended outcome (Dosi et al. 2000). Additionally, managers must ensure the reproducibility of capabilities through routinely practicing, repeating, and patterning them. Managerial decisions regarding the firm’s asset portfolio limit its scope of strategic action—at least in the short term. Company performance ultimately results from the managerial capability to continuously design effective strategies (Adner and Helfat 2003; Beck and Wiersema 2013). We have summarized these interrelationships in Fig. 1.

This study will expand upon the dominant focus on top managers (e.g., Smith and Tushman 2005; Kor and Mesko 2013) by including middle managers. Middle management decisively influences strategy formulation (B. Wooldridge et al. 2008) and business model implementation (Islam 2019) by shaping how capabilities are created and deployed. Increasing decentralization, global dispersion, and knowledge intensity have additionally led to an ongoing shift toward flatter hierarchies (Rajan and Wulf 2006). Middle managers are consequently in an increasingly critical position to ensure the success of business model innovation.

2.1.2 Managerial human capital

The three drivers of dynamic managerial capabilities originate from managers’ innate abilities and past experiences (Beck and Wiersema 2013). These capabilities individually and jointly determine the managerial ability to configure, develop, and deploy the firm’s asset portfolio in dynamic environments (Adner and Helfat 2003).

Human capital entails the entirety of managerial knowledge, capabilities, and competencies acquired through, for example, education, training, or prior work experience (Adner and Helfat 2003). Digital technologies have reshaped traditional learning opportunities by facilitating highly individualized training environments (Schneider 2018).

Two specific types of managerial human capital are tightly linked to firm innovation (Subramaniam and Youndt 2005). Leadership skills encompass managers’ exploitative capabilities, while entrepreneurial skills focus on their explorative capabilities (Ireland et al. 2001). A high leadership skill level allows managers to effectively organize, allocate, and configure the firm’s asset portfolio. These skills consequently help solidify existing competitive advantages (Ireland et al. 2001; Guo et al. 2013). Managers with a high level of entrepreneurial skills are conversely more alert toward new business prospects, better at construing ambiguous information, and more prone to design innovative business models (Teece 2007). Entrepreneurial action is consequently fundamental for exploring new markets, customers, or resources and combining those assets through novel business models (Ireland et al. 2001; Smith and Gregorio 2017). Altogether, a holistic assessment of managers’ human capital calls for the inclusion of these two types of human capital, as they are both required to design and implement business models that sustain competitive advantages in the long run.

2.1.3 Managerial social capital

Managerial social capital constitutes the second driver of dynamic managerial capabilities (Adner and Helfat 2003). We define managerial social capital as goodwill (e.g., trust, sympathy, reciprocity), which originates from informal and formal social ties within the organization (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998; Adler and Kwon 2002). Managers employ social capital to access tangible (e.g., money, equipment, investments) and intangible resources (e.g., information, knowledge, capabilities, commitment) from their social network (Weiler and Hinz 2019). Consequently, social capital facilitates innovation by increasing the interaction within the manager’s network (Gant et al. 2002).

Following Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), we differentiate between three interrelated dimensions of social capital. The structural dimension encompasses general network characteristics, such as the types of actors and their communication forms. The relational dimension describes the nature of personal relationships. Based on past interactions, people develop a unique affiliation with a specific network, which materializes in their behavior (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). The cognitive dimension refers to shared beliefs, values, norms, and attitudes within the network (Andrews 2010). Altogether, the structural dimension of social capital makes resources available, while the relational and cognitive dimensions determine the capacity to tap into those resources (Ali-Hassan et al. 2015). In addition to the multifaceted nature of social capital, all dimensions promote certain behaviors within specific social boundaries (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998).

2.1.4 Managerial cognition

Finally, dynamic managerial capabilities are composed of managerial cognition (Adner and Helfat 2003). This “cognitive capital” (Helfat and Martin 2015b, p. 427) refers to the method of information processing that originates from cognitive processes and structures (Walsh 1995). Based on past experiences and learning, managers develop unique cognitive frames through which they process information (Karhu and Ritala 2020). These mental templates shape the individual perspective in specific choice situations. To make sense of information, managers mentally frame information (Walsh 1995). This highly individual interpretation of information drives decision-making by determining “how a given problem or decision is perceived” (Karhu and Ritala 2020, p. 490). Ultimately, managerial cognition serves as the basis for managerial decision-making by governing the extent of consciousness and thus the intentional evaluation of information (Walsh 1995; Adner and Helfat 2003).

Information processing can fundamentally occur in two ways. Within the automatic processing mode, individuals examine information on a solely superficial level as they resort to past experiences in comparable situations. Automatic processing thus aims to facilitate cognitive efficiency by reducing complexities and uncertainties. The controlled processing mode is, in contrast, shaped by the current informational context. It is most applicable in novel situations, for which decision-makers do not possess readily available knowledge structures (Walsh 1995; Kahneman 2012).

Real-world decision-making is characterized by the necessity to process information efficiently by developing cognitive simplifications. Due to their limited attentional and cognitive capacities, managers cannot notice or interpret the entire scope of information (Walsh 1995). Consequently, the automatic processing mode is most applicable in relatively stable conditions, in which it enables a higher level of cognitive efficiency. In dynamic environments, however, the existing mental models can quickly become obsolete. Outdated cognitive processes and structures will cause inadequate decisions (Tripsas and Gavetti 2000; Beck and Wiersema 2013). Automatic information processing also inhibits creative problem solving, as managers tend to develop incomplete and biased perspectives, ignore discrepant but perhaps important information, and base their decisions on simplified decision rules (Walsh 1995). Altogether, a high level of cognitive capability equips the manager with the analytical skillset required to cope with environmental change proactively (Helfat and Martin 2015a).

We view strategic decision-making as an ongoing feedback loop (see Fig. 2). In this recursive process, managers construe an imperfect mental representation of the internal and external informational environment. Due to limited attentional and cognitive capacities, not all relevant information will enter the decision-making process. Cognitive structures and processes are consequently highly individual and imperfect (Walsh 1995). Ergo, heterogeneity in managerial cognition shapes company strategy by causing differences in the managerial ability to sense, seize, and reconfigure the firm’s asset portfolio (Adner and Helfat 2003; Helfat and Peteraf 2015).

An organizing framework of managerial cognition, based on Walsh (1995)

2.2 The business model concept

2.2.1 Digital business models

The digital transformation continues to pressure managers to rethink existing business models for two main reasons. First, the widespread use of digital technologies has caused a paradigm shift from physical to intangible value offerings (Iansiti and Lakhani 2014). Second, the business model itself has turned into a subject of innovation. Companies can create additional value by designing business models that supplement their efforts toward product, process, and service innovation (Purkayastha and Sharma 2016; Clauss et al. 2019b). Consequently, managers are challenged to design business models that bridge the gap between the technological and economic realms in the face of internal hindrances and external uncertainties (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002; Bouncken et al. 2021).

We define the business model from two perspectives. The objective view conceptualizes the business model as the holistic and interdependent logic of value proposition, value creation, and value capture (Morris et al. 2005; Massa et al. 2017; Clauss et al. 2019a). The value proposition reflects what kind of value the firm offers to whom and through which channels (Morris et al. 2005). The value creation dimension describes how companies create value along their entire value chain. It hence specifies underlying resources and processes (Clauss 2017). Value capture maps out how firms commercialize value (Morris et al. 2005) through either revenue streams (Casadesus‐Masanell and Zhu 2013) or revenue models (Baden-Fuller and Haefliger 2013). By determining and transcending organizational boundaries and allowing firms to be ambidextrous, inimitable business model configurations build the foundation of sustained competitive advantages (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002; Morris et al. 2005). Second, the cognitive view defines the business model as an implicit managerial mental scheme that shapes decision-making by filtering and simplifying information (Massa et al. 2017). From the managerial perspective, this mental picture of the business model is a subjective view of how the firm proposes, creates, and captures value. Decision-making related to the business model ultimately rests on the manager’s subjective perception of its operating principles and not its objective design (Tikkanen et al. 2005; Massa et al. 2017).

2.2.2 A processual view of business model innovation

Business model innovation generally refers to novel, designed, and nontrivial changes to how the firm proposes, creates, and captures value or how these three domains are linked (Foss and Saebi 2017). Business model innovation can range from incremental changes within isolated areas to the fundamental renewal of the business model. Additionally, it might even cause the implementation of a secondary business model (Khanagha et al. 2014). Due to their magnitude, business model innovation regularly results in corresponding alterations to the firm’s strategy and asset portfolio (Helfat and Martin 2015b).

To systematically analyze business model innovation, we adopt the processual 4I-framework of business model innovation (for this and the following, Frankenberger et al. 2013; Gassmann et al. 2014). This framework proposes an iterative four-phased sequence. During the initiation phase, managers focus on monitoring and interpreting change processes within the competitive and technological environment. In the ideation phase, managers subsequently transform identified change drivers into concrete ideas for business model innovation. Managers must translate those ideas into concrete business model designs in the integration phase. In the final implementation phase, managers must realize business model innovation. Altogether, effective management is essential to ensure the fit between (1) the envisaged business model innovation and the demands of the environment (i.e., the external fit), (2) the newly generated ideas for business model innovation and their transformation into realizable approaches (i.e., the internal fit), and (3) the design and realization phase.

3 The effects of dynamic managerial capabilities

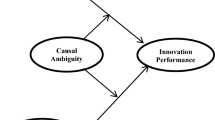

We subsequently derive a research model at the individual managerial level. As depicted in Fig. 3, managerial human capital, managerial social capital, and managerial cognition shape creativity, innovation, and strategic change through their distinct interactions (Helfat and Martin 2015b). We choose managerial cognition as the dependent variable to gain more insights into the underlying mechanisms of business model innovation. Managerial cognition ultimately determines how managers subjectively evaluate the current business model and possible options for its redesign. Differences in those cognitive evaluations materialize in the concrete business model configuration by influencing the recognition of change and the disposition to act on those recognitions (Adner and Helfat 2003; Cavalcante et al. 2011). In line with previous research (e.g., Tikkanen et al. 2005; Aspara et al. 2013), we infer that managerial cognitive capabilities determine strategic change through business model innovation in dynamic environments.

We hypothesize that managerial human capital and managerial social capital are positively related to the intentional evaluation of alternatives for redesigning the current business model. Furthermore, we posit that managerial human capital and managerial social capital reinforce each other.

During the four-phased business model innovation process, managerial capabilities play a decisive role in shaping the cognitive evaluation of information. In the initiation phase, managerial human capital supplies the necessary breadth of knowledge and experiences. Consequently, managers are better skilled to proactively identify and realistically evaluate external developments (Bock et al. 2012). Especially during the first phase, leadership skills are vital, as managers need to continually adjust the firm’s asset portfolio to ensure the constant availability of required resources and capabilities. Managers with a high level of entrepreneurial skills additionally show more tolerance of ambiguities. Those managers consequently possess the necessary capabilities to monitor technological and competitive change processes, challenge the status quo, and piece together unrelated issues (Tang et al. 2012). Furthermore, entrepreneurial managers regard the complex network of social relationships as a potential source of inspiration for new business ideas (Gassmann et al. 2014). The goodwill available through social capital allows managers to integrate viewpoints divergent from their social fabric (Gant et al. 2002). Social capital also supports the development of cohesion, trust, and cooperation within the firm. It thereby facilitates the exchange of heterogeneously distributed resources, information, and knowledge (Manev et al. 2005; Alguezaui and Filieri 2010). Furthering an in-depth understanding of the needs and demands of relevant players and the implications of emerging change drivers is especially crucial in the context of business model innovation (Frankenberger et al. 2013). Altogether, managerial human capital and managerial social capital determine the extent to which decision-makers meet the challenges of the initiation phase.

Generating new ideas for business model innovation is the main challenge during the subsequent ideation phase (Frankenberger et al. 2013). Over time, managers develop a subjective view of how the firm operates through its business model (Prahalad 2004). Strengthened by the historically grown allocation of assets, adhering to the dominant logic hinders decision-makers from experimenting with new business models (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002). While this dominant business model logic rests on dynamic managerial capabilities (Kor and Mesko 2013), those capabilities are at the same time needed to overcome entrenched viewpoints. Therefore, effective management in a digital economy requires experimentation by questioning proven recipes for success and acting across industry sectors (Prahalad 2004). Managerial human capital and managerial social capital both assume a vital role in this process. Leadership skills equip managers with the necessary administrative skills to effectively govern idea creation. Entrepreneurial skills conversely entail the explorative capabilities required to overcome the dominant business model logic by facilitating out-of-the-box thinking. Without sufficient entrepreneurial skills, managers cannot design an innovative business model to commercialize the value of innovation. Hence, entrepreneurial skills function as a leverage mechanism of leadership skills (Guo et al. 2013; Smith and Gregorio 2017). Managerial social capital also creates favorable conditions for innovation processes by promoting information exchange through nonhierarchical and informal networks (Gant et al. 2002). Therefore, high levels of social capital guarantee the necessary informal support for business model innovation and complement managers’ formal power.

In summary, managerial human capital and managerial social capital are conduits to overcoming the dominant business model logic and establishing the appropriate organizational setting for business model innovation. Decision-makers need to resort to their entrepreneurial skills to design new methods explicitly tailored for idea generation and subsequently ensure their functionality through applying leadership skills. Social capital guarantees the necessary dissemination and support of those new methods and mindsets within the organization. Due to the ambiguous and complex nature of business model innovation, different types of knowledge must be coherently integrated (Eppler et al. 2011). Furthermore, both capability types are also likely to ensure the external fit between the ideation and initiation phases, as they facilitate the situational analysis of the external environment during the initiation phase.

Exploitative managerial capabilities are critical during the integration phase. Management is faced with a twofold challenge to ensure internal fit. First, the effective orchestration of the firm’s asset portfolio rests on an in-depth elaboration of its strategic focus. In addition, decision-makers need to ensure the constant alignment between strategic and operative processes (Al-Debei et al. 2008). Leadership skills, in particular, enable effective asset portfolio orchestration. These skills also ensure the consistent alignment of processes by facilitating the goal-directed delegation of firm members (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010; Guo et al. 2013). Simultaneously, external fit constitutes a central success factor (Frankenberger et al. 2013; Gassmann et al. 2014). To establish viable partner management within the firm, managers resort to their human capital. Leadership skills are of integral importance during this phase, as effective asset orchestration rests on value-promising partner management. Moreover, strong social structures foster information exchange, whereby the firm benefits from the increased spread of insights through its partner management (Manev et al. 2005). A company’s partner management must finally exhibit an adaptive character, as a reinforcement of firmly established practices might result in nonsituational decision outcomes. In this case, managers base their decisions on outdated beliefs about the needs of stakeholders. The availability of managerial human and managerial social capital also ensures the internal fit between the ideation and integration phases. The combined application of entrepreneurial skills and social capital allows managers to explore new ideas for business model innovation. The implementation of those ideas, in contrast, requires their exploitation using leadership skills leveraged through social capital. Therefore, both drivers of dynamic managerial capabilities decisively shape the goal-directed business model transformation process. A coherent business model redesign ensures the fit between the ideas generated for business model innovation, the business model’s building blocks, and the building blocks themselves (Frankenberger et al. 2013).

In contrast to the primarily abstract managerial tasks during the first three phases, the implementation phase is concerned with realizing business model innovation (Gassmann et al. 2014). Managers must ultimately convince other company members of the necessity for change and ensure the commitment of key decision-makers. The role of dynamic managerial capabilities becomes evident in overcoming the dominant business model logic; managers need to resort to their controlled processing to assess the far-reaching implications of business model change holistically. This assessment, however, is only possible if managers possess the necessary human capital while employing their social capital to disseminate the new mindset. Company members must ultimately come to a shared belief system regarding the importance and execution of the transformation process (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998; Benner and Tripsas 2012). If managers do not possess a high level of social capital, isolated and diverging thought patterns are likely to result. These factors will impede a uniform definition of objectives and consequently impair the effective execution of business model innovation. Based on those interrelationships, we derive the following effect mechanism. To consciously analyze the options for business model change, managers need to possess a broad pool of knowledge to categorize and evaluate new information. The dissemination of knowledge depends upon sufficient goodwill (i.e., social capital), which is necessary to transcend entrenched mindsets and ensure the commitment of key decision-makers. Therefore, managerial capabilities are a central success factor for realizing business model innovation (Gassmann et al. 2014). Compared to other forms of innovation, business model innovation also causes more fundamental and wide-reaching changes. Management must hence demonstrate an openness to new ideas and an entrepreneurial spirit to continuously question the status quo (Giesen et al. 2010). Learnings acquired from previous iteration processes should always inform future decision-making (Sosna et al. 2010). This type of trial-and-error learning calls for managers who possess entrepreneurial skills and employ their social capital to ensure the spread of knowledge. Additionally, managers need to possess a high level of leadership skills to manage the process of business model innovation effectively.

In sum, the business model innovation process rests on the following logic. Human capital entails the managerial capability to identify, assess, and act on possible pathways for business model innovation. In particular, entrepreneurial skills enable managers to identify options for business model innovation and their subsequent realization (Chesbrough and Rosenbloom 2002). Managerial social capital also drives business model innovation by facilitating the exchange of resources and ensuring the necessary support within the organization. At the same time, managers’ human capital and social capital supplement each other. Highly skilled managers are more attractive as relationship partners, while a high level of social capital eases the access to resources, capabilities, and information required to design, support, and realize business model innovation. Based on those interrelationships, we postulate the following four hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

Higher levels of managerial human capital will lead to a more conscious evaluation of alternatives for business model innovation.

Hypothesis 2

Higher levels of managerial social capital will lead to a more conscious evaluation of alternatives for business model innovation.

Hypothesis 3a

Managers with higher levels of human capital will possess higher levels of social capital.

Hypothesis 3b

Managers with higher levels of social capital will possess higher levels of human capital.

4 Methodology

4.1 Data collection and sample

This study draws on a written survey of companies from German-speaking countries conducted during the last months of 2019. Our survey technique follows the key informant approach (Lechner et al. 2006). We acquired contact information through exhibitor lists from trade shows covering the entire spectrum of smart and digital automation, referred to as Industry 4.0. Firms operating within innovative and knowledge-intensive industries are appropriate subjects for our study. They are faced with disruptive changes in their fast-paced business environments and correspondingly need to possess dynamic managerial capabilities to cope with the need for rapid innovation processes (Schneider 2018). More specifically, we contacted exhibitors from the following international trade shows: Smart Production Solutions (focus: smart and digital automation), Hannover Messe (focus: industrial transformation), EuroShop (focus: retail trade), Medica (focus: medical industry), and Photokina (focus: photography, video, and imaging).

We distributed the questionnaire to a total of 2,920 companies using the web-based online survey tool Qualtrics. The initial response rate was 7.02% (N = 205). The questionnaire was structured as follows. After a short introduction to the study, we collected general data about the respondent. In the next block of questions, we individually measured dynamic managerial capabilities with a five-point Likert-type scale. We present the operationalization of the constructs in the following chapters. In the fourth and final part of the questionnaire, we gathered general company data.

4.2 Measures

4.2.1 Dependent variable

We conceptualize managerial cognition concerning the business model (see Appendix). In this sense, managers develop a unique cognitive representation of the firm’s business model. This highly individual interpretation entails the managerial perception of the business model’s three core building blocks. Therefore, we define managerial cognition as the conscious evaluation of alternatives for business model innovation (Schrauder et al. 2018). Based on this cognitive perspective, Schrauder et al. (2018) generate a total of eleven items. We translated those items into German. Additionally, we modified the initial items to measure the extent to which managers resort to the automatic processing mode while evaluating the options for partial or complete business model innovation. Managerial cognition was inversely coded. Small values indicated automatic processing, while high values inferred that managers resort to the controlled mode of processing (i.e., they entirely focus their cognitive resources on evaluating the current business model). Consequently, we argued that managers can only modify established business model schemes by consciously and intentionally evaluating the existing business model and possible options for its redesign.

4.2.2 Independent variables

We measured managerial human capital by resorting to the duality of leadership skills and entrepreneurial skills (see Appendix). Based on the work of Chandler and Hanks (1998), Guo et al. (2013) developed a five-item measurement of those two dimensions. We translated those items into German.

Our operationalization of managerial social capital builds on Carr et al. (2011) (see Appendix). We modified the original items to measure social capital at the individual managerial level. We maintained the division of social capital into structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions. We translated those items into German.

4.2.3 Control variables

We controlled for three variables at the managerial level: (1) gender, which was coded as a binary variable (male = 0; female = 1); (2) management level,which was divided into middle management, top management, and owner/shareholder; and (3) functional background, which was classified as output functions (i.e., marketing, sales, research and development), throughput functions (i.e., production, accounting, process engineering), and peripheral functions (i.e., law, finance) (Herrmann and Datta 2005). We included these variables to account for their possible effects on managers’ cognitive processes. First, prior research has shown that gender impacts strategic decision-making by causing differences in the propensity for risk-taking (Croson and Gneezy 2009). Second, the hierarchical position influences the exchange and flow of information within the firm (Ethiraj and Levinthal 2004). Last, functional background shapes decision-making by being the source of highly personal perceptions (Herrmann and Datta 2005).

4.3 Statistical procedure

Using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26, we first constructed the variables for dynamic managerial capabilities using principal axis confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We determined the optimal allocation of items by applying varimax rotation. We excluded missing values listwise. We asserted the basic eligibility of factor analysis by the Bartlett test of sphericity, the measure of sample adequacy (MSA) criterion, and the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) criterion (Hair et al. 2014). We used the Kaiser-Guttman (KG) criterion to determine the appropriate number of factors and then conducted a scree test to assess the factors’ robustness (Thompson 2004). In general, we only constructed a factor if it consisted of at least three variables and factor loadings exceeded 0.30 (Hair et al. 2014).

We assessed the quality criteria as follows. First, we classified factors with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients greater than 0.70 as reliable (Hair et al. 2014). Second, we determined validity using convergent and discriminant validity. While the former calls for an average variance extracted (AVE) over 0.50, the latter requires a minimum factor loading of 0.50 and the fulfillment of the Fornell-Larcker (FL) criterion (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Last, objectivity demands include the objectivity of application (i.e., standardized test situation), the objectivity of analysis (i.e., unbiased analysis), and the objectivity of interpretation (i.e., independent interpretation) (Resnik 2001; Payne and Payne 2004).

We tested our hypotheses using multiple regression analysis. We additionally assessed those results by constructing a structural equation model using R and its lavaan extension (Rosseel 2012). We defined significance levels as extremely significant (p ≤ 0.001), highly significant (p ≤ 0.01), and significant (p ≤ 0.05) (J. M. Wooldridge 2019). We classified effect sizes as strong (β > 0.35), moderate (β > 0.15), and weak (β > 0.02) (Cohen 1988).

5 Results

5.1 Measurement model

We conducted a CFA of all drivers of dynamic managerial capabilities and their respective dimensions. We only included data sets if the respondent indicated a current management affiliation within the firm. The Bartlett test of sphericity generally confirmed the basic data eligibility as extremely significant for each factor (p < 0.001; for this and the following, see Table 1). The MSA criterion and the KMO criterion confirmed these findings. The CFA of managerial human capital indicated a two-factor solution for its leadership skills dimension, while entrepreneurial skills loaded onto a single factor. Even though the KG criterion and the scree test validated those results, the item composition of leadership skills had to be modified. We excluded item 3 because its factor loading fell short of 0.50. We also removed item 1 because it showcased a loading onto a second factor while not loading sufficiently onto the same factor as the remaining items. Leadership skills were therefore comprised of items 2, 4, and 5. The variable composition of entrepreneurial skills was not modified.

Subsequently, we assessed the item composition of managerial social capital. In the first step, we confirmed the theoretical tripartite structure of social capital. We excluded three items due to a factor loading smaller than 0.50. The modified item composition yielded a two-factorial solution, in which we removed item 1 of the structural dimension (factor loading < 0.50). Both the KG criterion and the scree test attest to those results. In the third and last step, we extracted two factors for managerial social capital. All the remaining item loadings exceeded 0.50.

The CFA of managerial cognition confirms the proposed structure of value offering, value architecture, and value capture. We precluded items 1 and 5 of the architectural dimension from further analyses, as their factor loadings were below the cutoff value. The KG criterion and scree test confirmed those findings.

Hereafter, we evaluate the quality of our data (see Table 1). All factors are reliable (α > 0.70). Managerial cognition is convergent valid (AVE > 0.50). Managerial human and social capital are also convergent valid, as their respective AVE is between 0.40 and 0.50, while their Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceed 0.60 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). All factors are discriminantly valid and meet the defined quality criteria. The test situation was fully standardized throughout this study, and the data were objectively analyzed and interpreted. Our study hence complies with all objectivity demands.

5.2 Descriptive statistics and bivariate results

In the next step, we calculated the descriptive statistics and correlations (see Table 2). The managers within the sample are, on average, 45.55 years old, primarily male (83.72%), identify as owners/shareholders or top managers (74.42%), and perform an output function (91.86%). We assessed their qualification as key informants by calculating the average years of firm affiliation. On average, the respondents have worked at their current firm for 13.42 years. This long tenure serves as a suitable indication of their qualification as key informants. The firms within the sample are primarily based in Germany (93.91%). They operate within five industries, which we classified according to the following Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes: service providers (SIC 8; 28.30%), producers of capital goods (SIC 4; 25.47%), producers of consumer goods (SIC 3; 23.58%), retail and wholesale (SIC 6; 20.75%), and transport and logistics (SIC 5; 1.89%).

5.3 Regression results

We list the regression results in Table 3. Hypotheses 1 and 2 predicted a positive effect of managerial human and managerial social capital on managerial cognition related to business model innovation, respectively (see Table 6). Hypothesis 1 is confirmed, as managerial human capital is found to exert a highly significant, moderate to strong effect on managerial cognition related to business model innovation (b = 0.278, se = 0.086, p = 0.002). The data also supports Hypothesis 2. Managerial social capital shows an extremely significant, strong effect on managerial cognition related to business model innovation (b = 0.293, se = 0.075, p < 0.001). We subsumed a reciprocal positive effect between managerial human and managerial social capital in Hypotheses 3a and 3b. While the data show this proposed positive relationship between both variables, the coefficients are statistically insignificant (Hypothesis 3a: b = 0.151, se = 0.127, p > 0.237; Hypothesis 3b: b = 0.114, se = 0.096, p = 0.237). Thus, we consequently reject Hypotheses 3a and 3b.

The structural equation model confirms these results (see Tables 4 and 5). Managerial human capital (b = 0.278, se = 0.083, p < 0.001) and managerial social capital (b = 0.293, se = 0.072, p < 0.001) both exert an extremely significant effect on managerial cognition related to business model innovation. Conversely, there is no significant covariance between managerial human capital and managerial social capital (b = 0.051, se = 0.043, p > 0.233). As summarized in Table 6, the data set significantly supports Hypotheses 1 and 2 but not Hypotheses 3a and 3b. Figure 4 shows the respective path coefficients within our research model.

6 Discussion

6.1 Theoretical contributions

Our first research goal was to operationalize the three drivers of dynamic managerial capabilities from a multidimensional perspective. Based on this methodology, our second objective was to analyze the unique interactions of dynamic managerial capabilities in the context of business model innovation.

Our findings confirm Adner and Helfat’s (2003) basic notion of dynamic managerial capabilities, as heterogeneity in dynamic managerial capabilities stems not only from differences within the three underpinnings but also from their unique interactions. The results indicate that human capital and social capital decisively shape how managers cognitively evaluate options for business model innovation.

First, our findings underline the importance of managerial human capital as the basis of knowledge and experience for strategic decision-making. The data show that managers with higher levels of human capital will evaluate the opportunities and risks of business model innovation more consciously than those with lower levels of human capital. Therefore, managers with higher levels of human capital are more prone to resort to the controlled mode of information processing than their counterparts. Future research could examine whether the mode of information processing materializes in the design and ultimate success of business model innovation. Scholars could also test whether managerial cognition increases managerial human capital through conscious and in-depth information processing.

Additionally, our data set shows that managerial social capital is a significant antecedent to managerial cognition. These results validate the prevailing view of social capital as a facilitator of information exchange and decision-making quality (Manev et al. 2005; Alguezaui and Filieri 2010). Through increased trust, collaboration, cooperation within the organization, managerial social capital provides access to a greater breadth and depth of information. This wealth of information allows for a more conscious evaluation of business model innovation by providing the necessary information to question existing mental models. Hence, managers with higher levels of social capital are more likely to resort to the controlled mode of information processing. Future research could examine a potential recursive effect between managerial social capital and managerial cognition. Conscious information processing allows decision-makers to analyze the challenges associated with business model innovation more comprehensively and develop a more profound understanding of the needs and demands of key players.

Contrary to our expectations, we find an insignificant albeit positive effect of managerial human capital on social capital and vice versa. These findings contrast the existing studies on the relationship between both forms of capital, which confirm human and social capital as substitutes or complements (e.g., Santarelli and Tran 2013). One possible explanation might be the unique context of business model innovation. This form of innovation takes place in an ambiguous environment characterized by enormous pressure for success. It seems plausible that highly skilled managers might be more reluctant to form new relationships due to the fear of knowledge drain. It is also possible that highly connected managers are more averse toward external knowledge, as they are inclined to primarily base their decisions on what they know for sure. Our findings might also point to more complex mechanisms. The relationship between managerial human and social capital is potentially mediated by omitted interpersonal factors, such as expectations and obligations or norms and sanctions (e.g., Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Last, culture might influence the relationship between managers’ human and social capital. The previously mentioned study by Santarelli and Tran (2013) analyzed human and social capital in Vietnamese firms. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions study has shown that Vietnamese culture is driven by collectivistic tendencies, whereas German culture is highly individualistic (Hofstede Insights 2021). These cultural differences might ultimately cause differences in how important social capital is in the context of a specific country. Hence, previous studies in collectivistic cultures have confirmed a reinforcing relationship between human and social capital (e.g., Santarelli and Tran 2013), while we could not demonstrate this linkage in an individualistic culture.

In summary, our contributions to the literature are fourfold. First, we derived precise definitions for all relevant constructs. Second, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to employ a survey-based multidimensional operationalization of dynamic managerial capabilities. Third, we move beyond partially analyzing dynamic managerial capabilities by examining the interrelationships between all underlying dimensions. Finally, fourth, we have further strengthened the importance of dynamic managerial capabilities in the context of business model innovation.

6.2 Managerial implications

Beyond its theoretical contributions, this study has substantial implications for managerial practice. On the one hand, we advise firms to invest substantial resources in managerial training and education. Our research has demonstrated that higher levels of managerial human capital will lead to a more conscious evaluation of business model innovation. Promoting an in-depth analysis of business model innovation will enhance the managerial ability to continuously align all interrelated elements of the business model with the demands of today’s dynamic environment. As previous research has shown, ensuring the constant adaptability of the business model is a central driver of long-term company success (Clauss et al. 2019a). On the other hand, organizational design should foster social relationships. Due to the interdisciplinary nature and its wide-reaching implications, successful business model innovation rests on the frequent interdivisional exchange of information between highly skilled managers. In particular, principal-agent theorists have long called for less hierarchical and more informal organizational structures to facilitate knowledge transfer and conflict resolution within organizations (Adler 2001). To promote the value and growth of managerial social capital by supporting resource exchange and managerial autonomy, we advise business practitioners to design “decentralized, informal and specialized organizational structures” (Andrews 2010, p. 588).

6.3 Limitations and recommendations for future research

In addition to its contribution to research and practice, our paper faces several limitations. First, the predominance of German firms within the sample impairs the generalizability of the findings. Further research could include cultural variables and test whether culture-specific management styles influence our findings. Second, our study focuses on business model innovation within digitally driven industries. Additional research needs to examine whether managerial activities toward business model innovation differ between increasingly digitalized industries. Third, we do not address how individual-level capabilities aggregate at the collective level. Scholars can build on our theoretical and empirical insights to build models at the management team level. Fourth, our statistical analyses indicate that other explanatory variables might exist. Therefore, future research should take other potential variables at the individual and organizational levels into account. Fifth, our study relies on cross-sectional data. As the development and sharing of knowledge are not static processes, a fruitful avenue for subsequent studies might be longitudinal data analysis. From a statistical perspective, we note additional possible limitations due to our relatively small sample size.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Åberg C, Torchia M (2020) Do boards of directors foster strategic change? A dynamic managerial capabilities perspective. J Manag Gov 24:655–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-019-09462-4

Acciarini C, Brunetta F, Boccardelli P (2020) Cognitive biases and decision-making strategies in times of change: a systematic literature review. Manag Decis Ahead-of-Print. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2019-1006

Adler PS (2001) Market, hierarchy, and trust: the knowledge economy and the future of capitalism. Organ Sci 12:215–234. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.2.215.10117

Adler PS, Kwon S-W (2002) Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Acad Manag Rev 27:17–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134367

Adner R, Helfat CE (2003) Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strateg Manag J 24:1011–1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.331

Al-Debei MM, El-Haddadeh R, Avison D (2008) Defining the business model in the new world of digital business. In: Proceedings of the 14th Americas conference on information systems AMCIS’08. Toronto, Canada, pp 1–11. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Defining-the-Business-Model-in-the-New-World-of-Al-Debei-El-Haddadeh/ec87172d69171cb545155ba13c3256776bca03d6

Alguezaui S, Filieri R (2010) Investigating the role of social capital in innovation: sparse versus dense network. J Knowl Manag 14:891–909. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271011084925

Ali-Hassan H, Nevo D, Wade M (2015) Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: the role of social capital. J Strateg Inf Syst 24:65–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2015.03.001

Andrews R (2010) Organizational social capital, structure and performance. Hum Relat 63:583–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709342931

Aspara J, Lamberg J-A, Laukia A, Tikkanen H (2013) Corporate business model transformation and inter-organizational cognition: the case of Nokia. Long Range Plan 46:459–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2011.06.001

Baden-Fuller C, Haefliger S (2013) Business models and technological innovation. Long Range Plan 46:419–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.08.023

Beck JB, Wiersema MF (2013) Executive decision making: linking dynamic managerial capabilities to the resource portfolio and strategic outcomes. J Leadersh Organ Stud 20:408–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051812471722

Benner MJ, Tripsas M (2012) The influence of prior industry affiliation on framing in nascent industries: the evolution of digital cameras. Strateg Manag J 33:277–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.950

Bock AJ, Opsahl T, George G, Gann DM (2012) The effects of culture and structure on strategic flexibility during business model innovation. J Manag Stud 49:279–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01030.x

Bouncken R, Kraus S, Roig-Tierno N (2021) Knowledge- and innovation-based business models for future growth: Digitalized business models and portfolio considerations. Rev Manag Sci 15:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00366-z

Carr JC, Cole MS, Ring JK, Blettner DP (2011) A measure of variations in internal social capital among family firms. Entrep Theory Pract 35:1207–1227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00499.x

Casadesus-Masanell R, Fen Z (2013) Business model innovation and competitive imitation: the case of sponsor-based business models. Strateg Manag J 34:464–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2022

Casadesus-Masanell R, Ricart JE (2010) From strategy to business models and onto tactics. Long Range Plan 43:195–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.01.004

Cavalcante S, Kesting P, Ulhøi J (2011) Business model dynamics and innovation: (re)establishing the missing linkages. Manag Decis 49:1327–1342. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741111163142

Chandler GN, Hanks SH (1998) An examination of the substitutability of founders human and financial capital in emerging business ventures. J Bus Ventur 13:353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00034-7

Chesbrough H, Rosenbloom RS (2002) The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind Corp Change 11:529–555. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/11.3.529

Clauss T (2017) Measuring business model innovation: Conceptualization, scale development, and proof of performance. RD Manag 47:385–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12186

Clauss T, Abebe M, Tangpong C, Hock M (2019a) Strategic agility, business model innovation, and firm performance: an empirical investigation. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 68:767–784. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2019.2910381

Clauss T, Bouncken RB, Laudien S, Kraus S (2019b) Business model reconfiguration and innovation in SMEs: a mixed-method analysis from the electronics industry. Int J Innov Manag 24:2050015. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919620500152

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

Croson R, Gneezy U (2009) Gender differences in preferences. J Econ Lit 47:448–474. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.2.448

Dosi G, Nelson RR, Winter SG (2000) Introduction: the nature and dynamics of organizational capabilities. In: Dosi G, Nelson RR, Winter SG (eds) The nature and dynamics of organizational capabilities. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 1–22

Eppler MJ, Hoffmann F, Bresciani S (2011) New business models through collaborative idea generation. Int J Innov Manag 15:1323–1341. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919611003751

Ethiraj SK, Levinthal D (2004) Bounded rationality and the search for organizational architecture: an evolutionary perspective on the design of organizations and their evolvability. Adm Sci Q 49:404–437

Felin T, Foss NJ, Heimeriks KH, Madsen TL (2012) Microfoundations of routines and capabilities: individuals, processes, and structure. J Manag Stud 49:1351–1374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01052.x

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18:39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Foss NJ, Saebi T (2017) Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: how far have we come, and where should we go? J Manag 43:200–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316675927

Frankenberger K, Weiblen T, Csik M, Gassmann O (2013) The 4I-framework of business model innovation: a structured view on process phases and challenges. Int J Prod Dev 18:249–273

Gant J, Ichniowski C, Shaw K (2002) Social capital and organizational change in high-involvement and traditional work organizations. J Econ Manag Strategy 11:289–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.2002.11.2.289

Gassmann O, Frankenberger K, Csik M (2014) The business model navigator: 55 models that will revolutionise your business. Pearson Education, Harlow

Giesen E, Riddleberger E, Christner R, Bell R (2010) When and how to innovate your business model. Strategy Leadersh 38:17–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/10878571011059700

Guo H, Xi Y, Zhang X et al (2013) The role of top managers’ human and social capital in business model innovation. Chin Manag Stud 7:447–469. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-03-2013-0050

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2014) Multivariate data analysis, 7th edn. Pearson, Harlow

Helfat CE, Martin JA (2015a) Dynamic managerial capabilities: review and assessment of managerial impact on strategic change. J Manag 41:1281–1312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314561301

Helfat CE, Martin JA (2015b) Dynamic managerial capabilities: a perspective on the relationship between managers, creativity and innovation in organizations. In: Shalley C, Hitt MA, Zhou J (eds) The Oxford handbook of creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship: Multilevel linkages. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 421–429

Helfat CE, Peteraf MA (2015) Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strateg Manag J 36:831–850. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2247

Herrmann P, Datta DK (2005) Relationships between top management team characteristics and international diversification: an empirical investigation. Br J Manag 16:69–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2005.00429.x

Hofstede Insights (2021) Country comparison. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/. Accessed 28 Jul 2021

Holzmayer F, Schmidt SL (2020) Dynamic managerial capabilities, firm resources, and related business diversification—evidence from the English Premier League. J Bus Res 117:132–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.044

Iansiti M, Lakhani KR (2014) Digital ubiquity: how connections, sensors, and data are revolutionizing business. Harv Bus Rev 92:1–11

Ireland RD, Hitt MA, Camp SM, Sexton DL (2001) Integrating entrepreneurship and strategic management actions to create firm wealth. Acad Manag Perspect 15:49–63. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2001.4251393

Islam S (2019) Business models and the managerial sensemaking process. Acc Financ 59:1869–1890. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12459

Kahneman D (2012) Thinking, fast and slow, 1st edn. Penguin, London

Kaplan S, Tripsas M (2008) Thinking about technology: applying a cognitive lens to technical change. Res Policy 37:790–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.02.002

Karhu P, Ritala P (2020) The multiple faces of tension: dualities in decision-making. Rev Manag Sci 14:485–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0298-8

Khanagha S, Volberda H, Oshri I (2014) Business model renewal and ambidexterity: structural alteration and strategy formation process during transition to a cloud business model. RD Manag 44:322–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12070

Kor YY, Mesko A (2013) Dynamic managerial capabilities: configuration and orchestration of top executives’ capabilities and the firm’s dominant logic. Strateg Manag J 34:233–244. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2000

Kraus S, Palmer C, Kailer N et al (2018) Digital entrepreneurship: a research agenda on new business models for the twenty-first century. Int J Entrep Behav Res 25:353–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2018-0425

Lechner C, Dowling M, Welpe I (2006) Firm networks and firm development: the role of the relational mix. J Bus Ventur 21:514–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.02.004

Manev IM, Gyoshev BS, Manolova TS (2005) The role of human and social capital and entrepreneurial orientation for small business performance in a transitional economy. Int J Entrep Innov Manag 5:298–318. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2005.006531

Martin JA (2011) Dynamic managerial capabilities and the multibusiness team: the role of episodic teams in executive leadership groups. Organ Sci 22:118–140. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0515

Massa L, Tucci CL, Afuah A (2017) A critical assessment of business model research. Acad Manag Ann 11:73–104. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2014.0072

Morris M, Schindehutte M, Allen J (2005) The entrepreneur’s business model: toward a unified perspective. J Bus Res 58:726–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.11.001

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad Manag Rev 23:242–266. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.533225

Payne G, Payne J (2004) Key concepts in social research. SAGE Publications, London

Penttilä K, Ravald A, Dahl J, Björk P (2020) Managerial sensemaking in a transforming business ecosystem: conditioning forces, moderating frames, and strategizing options. Ind Mark Manag 91:209–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.09.008

Prahalad CK (2004) The blinders of dominant logic. Long Range Plan 37:171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2004.01.010

Purkayastha A, Sharma S (2016) Gaining competitive advantage through the right business model: analysis based on case studies. J Strategy Manag 9:138–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-07-2014-0060

Rajan RG, Wulf J (2006) The flattening firm: Evidence from panel data on the changing nature of corporate hierarchies. Rev Econ Stat 88:759–773. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.4.759

Resnik DB (2001) Objectivity of research: Ethical aspects. In: Smelser NJ, Baltes PB (eds) International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. Pergamon, Oxford, pp 10789–10793

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48:1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Santarelli E, Tran HT (2013) The interplay of human and social capital in shaping entrepreneurial performance: the case of Vietnam. Small Bus Econ 40:435–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9427-y

Schneider P (2018) Managerial challenges of Industry 4.0: an empirically backed research agenda for a nascent field. Rev Manag Sci 12:803–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0283-2

Schrauder S, Kock A, Baccarella CV, Voigt K-I (2018) Takin’ care of business models: the impact of business model evaluation on front-end success. J Prod Innov Manag 35:410–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12411

Smith KG, Gregorio DD (2017) Bisociation, discovery, and the role of entrepreneurial action. In: Hitt MA, Ireland RD, Camp SM, Sexton DL (eds) Strategic entrepreneurship: creating a new mindset. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, pp 127–150

Smith WK, Tushman ML (2005) Managing strategic contradictions: a top management model for managing innovation streams. Organ Sci 16:522–536. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0134

Sosna M, Trevinyo-Rodríguez RN, Velamuri SR (2010) Business model innovation through trial-and-error learning: the Naturhouse case. Long Range Plan 43:383–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.003

Subramaniam M, Youndt MA (2005) The influence of intellectual capital on the types of innovative capabilities. Acad Manag J 48:450–463. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.17407911

Tang J, Kacmar KM, Busenitz L (2012) Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. J Bus Ventur 27:77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.07.001

Teece DJ (2007) Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg Manag J 28:1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

Teece DJ (2018) Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan 51:40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.06.007

Thompson B (2004) Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: understanding concepts and applications. American Psychological Association, Washington

Tikkanen H, Lamberg J, Parvinen P, Kallunki J (2005) Managerial cognition, action and the business model of the firm. Manag Decis 43:789–809. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740510603565

Tripsas M, Gavetti G (2000) Capabilities, cognition, and inertia: evidence from digital imaging. Strateg Manag J 21:1147–1161

Walsh JP (1995) Managerial and organizational cognition: Notes from a trip down memory lane. Organ Sci 6:280–321. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.3.280

Weiler M, Hinz O (2019) Without each other, we have nothing: a state-of-the-art analysis on how to operationalize social capital. Rev Manag Sci 13:1003–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0280-5

Wooldridge JM (2019) Introductory economics: a modern approach, 7th edn. Cengage Learning, Boston

Wooldridge B, Schmid T, Floyd SW (2008) The middle management perspective on strategy process: contributions, synthesis, and future research. J Manag 34:1190–1221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308324326

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. An external entity or grant did not fund this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Tim Heubeck. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tim Heubeck and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Consent to participate

Consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Operationalization of items (translated from German).

Construct | Dimension | Item |

|---|---|---|

Managerial human capital | Leadership skills | One of my greatest strengths is getting results by organizing and motivating people |

One of my greatest strengths is organizing resources and coordinating tasks | ||

One of my greatest strengths is my ability to delegate effectively | ||

One of my greatest strengths is my ability to monitor, influence, and lead people | ||

I make resource allocation decisions that achieve maximum results with limited resources | ||

Entrepreneurial skills | I like to think about new ways to do business | |

I frequently identify opportunities to start new businesses (although I may not pursue them) | ||

I often identify ideas that can be turned into new products or services | ||

I keep my eyes open for previously unnoticed entrepreneurial opportunities | ||

I see myself as a creator of entrepreneurial opportunities (entrepreneur) | ||

Managerial social capital | Structural dimension | I always communicate openly and honestly with other company members |

As a rule, I completely disclose my plans and intentions | ||

I willingly share information with other company members | ||

When exchanging information, I draw on my internal company relationships | ||

Relational dimension | I always have the utmost trust in other company members and their actions/decisions | |

I always act with integrity in my dealings with other company members | ||

In general, I have a high level of trust with other company members | ||

I am always considerate of the feelings and sensibilities of other company members | ||

Cognitive dimension | I feel committed to the goals of the company | |

I share a common purpose with other company members | ||

I see myself as a discussion partner in determining the company's direction | ||

My vision for the future of the company is in line with that of other company members | ||

Managerial cognition | When redesigning the business model in part or in whole, I consciously evaluate alternatives to a very high extent alternatives with regard to | |

Value offering evaluation | Customer problems and needs | |

Value propositions | ||

Relationships between value propositions and customer problems/needs | ||

Value architecture evaluation | Sales and distribution channels | |

Business transactions and the ways of collaborating with partners | ||

Linking business participants together in novel ways | ||

Taking over new value propositions or substituting existing parts of the value chain | ||

Applying new revenue streams | ||

Value capture evaluation | Resource requirements for all business aspects | |

The financial benefits for our company | ||

All the business-related costs of the project | ||

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heubeck, T., Meckl, R. Antecedents to cognitive business model evaluation: a dynamic managerial capabilities perspective. Rev Manag Sci 16, 2441–2466 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00503-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00503-7

Keywords

- Business model innovation

- Dynamic managerial capabilities

- Human capital

- Managerial cognition

- Organizational change

- Social capital