Abstract

European universities are experiencing increasing financial pressures. Given that governmental budgets are cut, they have to additionally rely on further sources of funding. Multi-party funding, however, is not easily managed and poses serious challenges on academic research. This study explores the question “What tensions result from multiple-party funding, what are possible consequences of the different funding strategies and—transferring the findings to the university context—how can universities establish and manage multiple-party funded research?” We conducted a qualitative single case study in a non-university research center (NRC). NRC has gone through the process of increasing financial pressure and now relies on multiple sources of financing that have to be managed concurrently. Our results discuss opportunities and threats and reveal core tensions related to multiple-party funding activities. Adopting a paradox lens allows us to transfer the insights from this case to the university context. We systematically discuss consequences for universities and academic research and suggest approaches of actively managing tensions via strategies of accepting, differentiating and integrating. We thereby contribute to the discussion how to establish and manage third-party funded research for European universities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Budget cuts of up to 48%. Changes to private financing that are not (yet) available. While other continents are investing, higher education in Europe is slipping into crisis (Headline of an Austrian daily newspaper article. Die Presse, 2011).

European universities face increasing pressures. Public funding decreases or fails to adjust to increasing student numbers (EUA – European University Association 2015). Governmental funding mechanisms more and more build on efficiency measures, output indicators or performance-based funding (Heckscher and Martin-Rios 2013). The landscape of European university funding is diverse and the country specifics vary. Still there is a trend towards increased third-party funding in academic institutions, including European or national research funds, private funding or collaboration with practitioners. As the competition for public grants is high (EUA 2015; bmwf 2016) private funding or collaborations with companies gain importance. Such cooperation offers promising opportunities for financing (Bonaccorsi et al. 2014) but also potential for serious risks. Collaborating with practitioners may negatively impact the core values of science (Wilholt 2010) or threaten the long-term perspective of public research (Geuna 2001). Authors like e.g. Kieser and Leiner (2009, 2012) even consider academia and practice as being “unbridgeable”.

Academic research reflects on these changes in the funding-landscape. Especially studies on university-industry collaborations increase and analyze the situation at the individual, the organizational or the institutional level (cf. Skute et al. 2017). To get a more fine-grained understanding of the phenomenon, also country specifics with regard to financing policies have to be considered. While countries such as the UK tend to rely most heavily on selective and mission-oriented policies, other countries on mainland Europe proportional allocation policies are still dominant (Geuna 2001). Nonetheless, there has been a move towards a contractual-oriented funding approach in all EU countries. Policy justification and rationalization becomes more and more important. “Thus, focusing [research] only on university-industry relationships can paint a misleading picture of the changes in public research.” (Geuna 2001, pp. 625–626).

This is particularly relevant as successful academic institutions build on a diversified funding base. The “entrepreneurial” university follows a clear strategic direction (Etzkowitz 2003) and combines (a) funding from governmental support, (b) financing from research, funds and (c) third-stream income including university-industry collaborations (Clark 1998, 2001). Managing multiple-party funding in this sense is far from easy. Integrating diverse stakeholder demands and pursuing multiple, sometimes contradictory goals fosters conflict and tensions throughout the organization (Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009).

We adopt a paradox perspective to elaborate on fruitful approaches to managing the tensions of multiple-party funding. Paradox studies aim at exploring how organizations can attend to competing demands simultaneously (Lewis 2000). Paradox is described as “contradictory yet interrelated elements that seem logical in isolation but absurd and irrational when [they appear] simultaneously” (Lewis 2000, p. 760). Tensions are the underlying source of paradox. Depending on how actors respond to tensions this may result in positive or negative dynamics (Smith and Lewis 2011; Lewis and Smith 2014). With regard to the academia-practitioner debate paradox scholars argue to confront the tensions and to find ways to actively manage them (Bartunek and Rynes 2014).

Empirical investigations of European universities with regard to multiple-party funding and resulting tensions are still scarce (Scholz et al. 2016). We thus conducted a qualitative single case study in a non-university research center (NRC) that has gone through the process of increasing financial pressure and relies on multiple sources of funding. The main research question is: “What tensions result from multiple-party funding, what are possible consequences of the different funding strategies and—transferring the findings to the university context—how can universities and academic institutions establish and manage multiple-party funded research?” This enables us to discuss lessons learned that are particularly relevant for multiple-party funding in academic institutions. We thereby focus on continental European universities, whose research tradition differs from other university systems such as the Anglo-Saxon academy and who face a fundamental transformation process concurrently (cf. e.g. Lenzen 2015). This study contributes to contemporary literature in three ways: First, it extends the ongoing discussion of the entrepreneurial university as our data empirically support Clark’s (1998, 2001) key argument that multiple-party funding can foster autonomy and consequently the pursuit of core societal goals. Second, by using paradox theory (Smith and Lewis 2011) we show that proactively handling tensions associated with multiple-party funding supports organizational success and sustainability. Third, this study is of practical relevance for universities, business schools, non-university R&D-focused organizations but also companies as it reveals promising avenues for pursuing diverging goals simultaneously.

We present the results of our study as follows: First, we reveal the context and consequences associated with public funding and self-financing. By adopting a paradox perspective we discuss core tensions that emerge from multiple-party funding. We show how NRC has dealt with tensions in this regard. We then systematically discuss the consequences for academia and suggest approaches on how to establish and manage third-party funded research.

2 The theoretical background

2.1 Mainland European universities under pressure

European universities face challenging times, especially those based on a continental European post-secondary education tradition like e.g. in Germany or Austria (Lenzen 2015). The role expectations for academic institutions change (Göransson and Brundenius 2011), cuts in public funding cause financial pressures (Sellenthin 2011), demands for organizational efficiency increase (Blaschke et al. 2014), and a more general discussion on academia’s autonomy and core values questions universities’ self-concept and identity (Wilholt 2010).

The role expectations for academic institutions change. With the rise of developed economies in Europe, knowledge gains increasing importance. The “triple helix” emerges as new metaphor where universities—besides governments and industries—are conceptualized as one of the strands for economic welfare and prosperous societies (Malone 2011). In this view knowledge acquisition, knowledge transformation and knowledge dissemination form the basis for economic competitiveness. Universities are expected to leave their “ivory towers” in order to become important players in the national innovation systems (Göransson and Brundenius 2011).

New demands challenge old forms of governance. Academic institutions experience a general trend towards more efficiency (Heckscher and Martin-Rios 2013). Governmental funding policies increasingly require efficiency measures, output indicators or performance-based funding. Measures encompass e.g. numbers for patents, Nobel Prize winners, enrolled students, graduates, doctorates, post-doc qualifications or publications (Schmoch 2011; Orr et al. 2009). In Austria, the idea of New Public Management—institutional autonomy and state control from the distance—resulted in new legal regulations for public and private academic institutions. Austrian higher education systems are now considered to be “corporations at public law” (Ash 2006) and obliged to implement quality management systems (AQ Austria—Agentur für Qualitätssicherung und Akkreditierung Austria 2016).

New developments question universities core values and identity. In many parts of central, eastern and northern Europe higher education has been historically influenced by the “Humboldtian idea”. In this tradition, academic education follows a holistic approach embedded in an environment where academic freedom is the highest good. This fundamentally differs from recent trends of vocational trainings to prepare students for a labor market. Thus, especially for academic institutions embedded in this rationale, such new developments lead to a questioning of their core values and identity (Ash 2006; Geuna 2001; Wilholt 2010).

Changing rationalities and their consequences for universities and academic research are particularly relevant for countries like Germany and Austria (that has been linking its economy closely to Germany). While these countries are known for enormous economic growth after World War II, today their economies are under pressure (OECD 2016, 2017). To stay competitive, such economies need a re-orientation towards other industrial sectors like e.g. microelectronics, information technology or biotechnology (Schmoch 2011). Universities play a pivotal role in this regard, as their research becomes more relevant for economic performance (Salter and Martin 2001). Thus, universities are expected to shift their research activities towards more applied research and joint research projects with enterprises. Funding strategies of federal governments explicitly focus on collaborative research with industrial firms and thus support this trend (Schmoch 2011).

Due to significant relationships between high rates of academic graduates and economic growth, federal governments attempt to heighten the share of academics among the working-age population (Schmoch 2011). This is one of the reasons for increasing student enrolments. Public budgets fail to adjust to increasing student numbers. As a consequence especially in countries such as Austria, Germany, Denmark, France or the Netherlands higher education systems are under pressure. This trend is further reinforced if in addition student numbers are growing faster than staff, as it is the case for example in Austria (EUA 2015).

2.2 Third-party funding: a promising pathway?

Financial constraint is, beside others, one of the key factors for researchers to collaborate with industry (Sellenthin 2011). University-practitioner collaborations allow universities to cover the deficits (Jones 2014) and to access additional sources for financing (Bonaccorsi et al. 2014). Such third-party research activities are multi-fold and encompass e.g. collaborative research, contract research or consulting (D’Este and Perkmann 2011). Opening universities to collaborations might also be an alternative way to respond to governmental attempts of increased administrative control in order to enhance efficiency (Heckscher and Martin-Rios 2013). Engagements with industry may support academics to further their research (D’Este and Perkmann 2011) and to drive publication productivity (Albers 2015).

In the late 1990s Clark (1998) already advocated the idea of the “entrepreneurial” university. His studies reveal a demand-response imbalance, where universities lack the capacity to adequately respond to increasing external demands. Two main reasons account for this imbalance: (1) Underfunding and (2) outdated organizational structures. To overcome the demand-response imbalance universities need a shift in self-perception towards the idea of the “entrepreneurial” university. This implies that academic institutions leave the role as victims behind and actively take the responsibilities given through governmental decentralization policies. The entrepreneurial university follows a clear strategic direction (Etzkowitz 2003): it pursues academic goals and simultaneously makes the knowledge produced available for economic or social use; it fosters business-like attitudes and qualities; and it integrates economic usefulness and efficiency as central components in their self-concept (Etzkowitz 2003). The pathways for successful transformation include a diversified funding base (building on governmental base funding, (governmental) research funds and third-stream income), a strengthened steering core, an extended developmental periphery, a stimulated academic heartland and an integrated entrepreneurial culture (Clark 2001). Third-stream income plays a pivotal role in the concept of the “entrepreneurial” university as income from other parties than government or (governmental) research funds enables universities to pursue their own strategies, to make self-reliant decisions and to strengthen their autonomy.

However, third-party funding can also be risky. Collaborations between industry and academic institutions may negatively impact the long-term perspective of public research (Geuna 2001) or scientific values in general (Wilholt 2010). Private firms or industrial partners want something for their money (Clark 2001). Contractual research is short-term oriented, targeted and aims to achieve certain results (Schmoch 2011). This might interfere with core academic values, that are to promote the development of scientific knowledge, to publish state-of-the-art research and to academically educate students (Brett 2000). Authors like Kieser and Leiner (2009, 2012) thus argue that academia and practice are two separate systems that follow their own logics and therefore cannot be integrated. Whereas scientific systems seek for truth in terms of true/false, attempt to generate theories and strive for scientific publication, practice systems “prefer acting to abstract thinking” (Kieser and Leiner 2012, p. 521; Isenberg 1984). Academia and practice are seen as being unbridgeable and thus the authors warn researchers to be aware of collaborating with practitioners. With regard to business schools, other management scholars take a different perspective. They warn business schools to be aware of being too academic and therefore distant from ‘the real world’. The science of management is often overemphasized at the expense of the value of practice and experience (Mintzberg 2004). Ghoshal (2005) points out that historically business schools have celebrated and accommodates plural kinds of scholarship—not only the scholarship of discovery (research), but also the scholarship of integration, of application, and of teaching. “Over the last 30 years, we have lost this taste for pluralism.” (Ghoshal 2005, p. 83) Demands for academic underpinnings of management education, reward systems that focus on publication in A-listed journals and educators that lack practical experience are some of the reasons for the scientific shift in business schools (Bennis and O’Toole 2005). As a consequence business schools fail to adequately prepare their students and to develop the competences needed for leading and managing in todays business world (Mintzberg et al. 2002). The relationship between business school research and the academy is far from easy (Tiratsoo 2004). It is therefore necessary to find new ways of balancing science and practice.

We adopt a paradox lens to add to this discussion. Academia and practice are distinct from each other, in some ways even contradictory. Despite this, they are closely interrelated, in some cases dependent on each other. Third-party funding plays a crucial role in this discussion. It might indeed threaten core academic values. Still, since the financial pressure put on universities seems to be inevitable, this theoretical lens might offer new viewpoints in what are the consequences from multiple-party funding for universities, their business schools and academic research.

2.3 A paradox lens on multiple-party funding

Public, social, non-profit, artistic or academic organizations in particular have a hard time in combining various—partly diverging—goals, such as social and financial, dealing with different—partly contrary—rationalities, such as academia, politics and economics and multiple—partly conflicting—stakeholder demands (Balser and McClusky 2005; Jäger and Beyes 2010; Salamon 1999). Contradictory goals and demands from various stakeholders different yet closely interrelated tasks and processes of organizing, as well as ambiguous and uncertain situations (Smith and Lewis 2011) spur and intensify tensions throughout the organization (Andriopoulos and Lewis 2009). In the presence of “contradictory yet interrelated elements that seem logical in isolation but absurd and irrational when [they appear] simultaneously” these tensions surface as paradoxes (Lewis 2000, p. 760). Tensions are the underlying sources of paradox and persist because of organizational complexity (Smith and Lewis 2011).

Lüscher et al. (2006), Lüscher and Lewis (2008) as well as Smith and Lewis (2011) elaborate on different types of paradoxes that represent core activities of organizing and elements of organizations. Paradoxes might emerge from opposing strategies to achieve performance that depends on various and often also competing goals such as financial and social. Such tensions are especially relevant for public and non-profit organizations since such organizations have to promote and protect special interests (van der Pijl and Sminia 2004) by serving public goods (Chisolm 1995; Kearns 1994) and acting as social services providers (Hodgkinson and Painter 2003). However, their basic mission and goals often interfere with the growing pressures for economic rationales (Jäger and Beyes 2010). Paradox might also occur from interactions between individuals and the collective, competing roles, values and memberships as studies of Golden-Biddle and Rao (1997) or Kreiner, Hollensbe and Sheep (2006) show. Paradoxes related to processes of organizing surface as complex systems create competing structures and processes to achieve a desired outcome. Literature refers to organizational designs in order to manage contradicting demands that emerge from conflicting organizational activities, such as the paradox of efficiency and flexibility (Adler et al. 1999) or the productivity dilemma (Benner and Tushman 2003). Paradoxes might also emerge with regard to learning processes through organizations’ endeavors to change, renew, or innovate while exploiting existing business models at the same time (March 1991). Since for learning organizations have to build upon, as well as destroy, the past to create the future (Tushman and O’Reilly 1996; O’Reilly and Tushman 2008) tensions might arise from conflicting demands in this regard.

Paradox studies aim at exploring how organizations can attend to such competing demands simultaneously (Cameron and Quinn 1988; Lewis 2000; Smith and Tushman 2005). A paradox perspective argues that long-term success is rooted in embracing paradox and depends on the organization’s continuous efforts to accept and meet multiple, divergent demands (Cameron 1986; Lewis 2000; Smith and Lewis 2011; Lewis and Smith 2014). Depending on how actors respond to paradoxes (Quinn 1988) they result in vicious or virtuous cycles. Vicious cycles describe the negative dynamics occurring when actors react defensively (Vince and Broussine 1996; Smith and Berg 1987) or try to suppress one pole at the expense of the other (Hofstadter 1979). Instead of approaching the paradox actors get caught within reinforcing cycles that perpetuate and intensify the tensions (Lewis 2000). Virtuous cycles, on the contrary, lead to positive, reinforcing effects between the opposing poles.

To capture the idea of proactive approaches to paradoxical phenomena literature uses different terms and expressions. From a logical perspective there are four different modes to work with paradox (Poole and van de Ven 1989): Opposition (juxtaposing the different elements and accepting and appreciating their difference), spatial or temporal separation (separating the different poles to different locations or different points in time) and synthesis (creating new conceptions by eliminating the oppositional nature of the poles). These modes might be analytically separated but practically combined. So accepting strategies might be a precondition for further resolution strategies (Poole and van de Ven 1989). Smith and Lewis (2011) distinguish between accepting and resolution strategies. Acceptance in the sense of embracing paradox and “live with it” (Clegg et al. 2002; Lewis 2000) builds the foundation for strategies that seek to successfully approach the underlying tensions (Smith and Lewis 2011). Jarzabkowski et al. (2013) identify three defensive approaches to respond to paradox labeled as splitting, suppressing and opposing and one active approach in terms of adjusting. Jay (2013) argues that the success of an organization’s innovation efforts depends on its ability to navigate paradox. Lewis and Smith (2014) introduce two distinct ways on how actors respond to paradox: (a) defensive or (b) strategic. In order to temporarily avoid or reduce strong negative emotions that emerge as paradox and tensions surface, actors may respond defensively and favor one pole at the expense of the other. Strategic responses attempt to engage the competing forces, by seeking to embrace, to cope with, and thrive through tensions.

A paradox lens thus offers possible strategies on how to deal with contradictory perspectives, goals or demands. It allows to see, e.g. academia and practice as being unbridgeable (Kieser and Leiner 2009), recognizes the contradictions between social and financial goals (Jäger and Beyes 2010) and is aware of the difficulties in meeting multiple, often contradictory demands (Balser and McClusky 2005). Still, a paradox perspective argues that it is important to actively address theses challenges instead of neglecting them or overemphasizing one pole of the paradox at the expense of the other (Smith and Lewis 2011).

With regard to the financing of academic institutions—especially those embedded in a continental European university tradition—the debate reveals the basic tension between scientific and societal mission and economic rationales. The scientific and societal mission—as one pole of the paradox—represents academia’s core values like producing scientific knowledge and research-based teaching in order to serve the society. This requires academic freedom, experiencing, risk taking, investing resources in unpredictable outcomes. The economic rationale—as the other side—follows a different logic. Effective processes and structures, formalization, risk avoiding, or saving resources are key issues in this regard. Thus, the two poles require a different kind of thinking and acting. Pursuing both is challenging. Bartunek and Rynes (2014), for example, elaborate in more detail on this and identify different types of paradoxical tensions in academic-practitioner relationships: Science and practice are different social systems that are self-referential and thus follow different logics, operate in different time dimensions, use different kinds of knowledge representations, prefer rigor over relevance or vice versa, and finally have distinct interests and incentives. Still, this relationship might also be framed as generative, mutually inspiring, or enabling more sophisticated (scientific) outcomes (Ambos et al. 2008; Bartunek and Rynes 2014).

Taken together, the debate whether excellent basic research and increased knowledge transfer resp. collaborations with practitioners contradict each other (cf. Van Looy et al. 2004) or whether economic goals interfere with core academic values (cf. Kieser and Leiner 2012) is still on-going. In any case, universities in general, and their business schools in specific, more and more rely on private money. It is therefore pivotal to actively manage arising tensions and to make use of their inherent potential for sustainable scholarship. This is far from easy and literature still lacks good examples on how this might work in practice. We thus conducted a single-case study in a non-university research organization that has gone through the process of increasing financial pressure. Insights from their approaches of managing the tensions of multiple-party funding contribute to the question on how universities might successfully handle this endeavor.

3 The empirical case

3.1 The perspective of a non-university research organization on challenges of multiple-party funding

We chose this case for mainly two reasons: Similarities in the process and the context. Strong similarities between the current situation of European universities and the organization we study allow for transferring insights from one organization that has gone through the process to others that are in the middle of this changing process. European universities, especially those following a continental European research tradition, become increasingly confronted with financial challenges. The organization we study has been dealing with similar challenges. Additionally, like universities that follow a continental European research tradition, this organization aims at societal impact based on the “freedom of art”. Similarities in the context and the self-concepts between universities and the organization we study may provide valuable insights concerning the current discussion on multiple-party funding in academic institutions embedded in a continental European research tradition. Whereas many European universities just begin to integrate self-financing issues into their self-concepts the organization we study already went through this process. This case thus provides empirical insights on how the integration of artistic, scientific and societal and economic goals may work in practice.

3.2 The case studied

Our single-case study (cf. Cresswell 2007; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007; Yin 2014) focuses on identifying how a publicly owned non-university research center manages multiple-party funding. This multi-unit artistic and research-focused organization—to which we give the fictional name NRC (“non-university research center”)—faces financial challenges in order to successfully operate in multiple very different worlds. NRC is supported by public funding as well as by different means of third-party funding. Sources for third-party funding are science funds and research grants but also industry-based private partners—amongst them many internationally known companies—which are very important to enable additional self-financing.

Although NRC is 100% publicly owned, currently it generates directly more than 60% of its annual budget. Currently, NRC consists of four distinct divisions or units that are nonetheless closely interwoven, constantly influence each other and are especially dependent from each other regarding financing issues. NRC’s 200 employees are lead by two CEOs at the top-level who split responsibilities as regards to contents and financial issues. Several unit-managers are responsible for the NRC’s divisions, such as the science lab and sales. Project-leaders manage diverse industry, scientific, and cultural projects.

3.3 The data

Our research relied on multiple sources of data, especially on interviews, documents, and observations (Patton 2002). We conducted qualitative interviews with both, current and former top-mangers, unit-managers from all divisions as well as project-leaders and employees (especially those that are responsible for fund-raising and conduct industry projects). We used a “maximum variation” technique to ensure maximum variety in the perspectives our informants represented (Miles and Huberman 1994). To collect our sample of interview partners, we started with staff in leading positions. In the course of our investigation we met several NRC employees and visited various sites and events. This allowed us to collect data based on informal talks and our own observations, both on the level of employees and on the level of NRC’s daily operations. Observational data stem from systematically observing and documenting diverse program activities (specific events, visits) as well as daily work interactions in all divisions. Archival data come from sources such as the comprehensive textbook on the organizational history, organizational archives (also online), financial reports, event brochures, newspaper articles and web material. Table 1 provides an overview of our data sources.

3.4 Analytical process

We based our analysis on the systematic, iterative interpretation and comparison of the data, cross-referencing the emerging categories with the existing literature (Gibbs 2007; Miles and Huberman 1994). We were particularly interested in elucidating NRCs diverse modes of financing reflected in many, different and interrelated projects in order to analyze their context and consequences for the organization and its overall vision. Based on a qualitative interpretive research methodology (Flick 2009) we applied a multiple step analysis as follows: First, we focused our analysis on the identification of various financing-methods within this organization. Second, we applied an in-depth analysis of approaches how to address these various methods of financing that stem from multiple-party means. We also analyzed practices that were applied in order to balance financial and other goals such as addressing public needs. By doing so, we examined our data and inductively developed first-order concepts, which we summarized into second-order themes that we aggregated into dimensions of narratives (Gioia et al. 2012). These analytical steps together enabled us to gain a comprehensive view about (1) how the organization manages multiple-party funding, (2) what tensions emerge from increasing third-party funding, (3) how are they managed and (4) what are the consequences for the organization and its overall vision. In Table 2 we summarize how we structured our data and how the communicative practices that address paradoxical tensions emerged from the narratives we identified.

In the following section we provide an overview of the identified tensions that multiple-party funding implies for NRC. In the discussion section we integrate and discuss our results in order to refine our understanding of multiple-party funding for universities and academic research in general. By comparing NRC’s situation with the situation many European universities are increasingly confronted with, we aim at providing “lessons learned” and thereby trigger the current discussion on challenges, threats but also opportunities for universities through third-party funding.

4 Research findings

4.1 The financial situation of NRC

NRC is a public, non-profit organization. Its core vision is to fulfill a societal and artistic duty by pursuing projects that “generate a societal, artistic, and scientific impact” (webpage). Interestingly our results reveal that NRC constantly emphasizes the interplay between these core values.

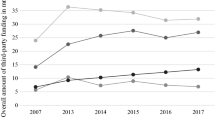

NRC is a public organization that is 100% owned by the City, however it strives to achieve high rates of self-financing. This is done with scientific and business projects. During an interview with the local press the financial director clearly points out: “We are a non-profit organization. Our aim is not to maximize profits but to establish high levels of self-financing.” Financial reports reveal that NRC’s rate of self-financing has been high since its beginnings and grew up to more than 60% in 2015. As the interviews with several unit heads and employees of NRC indicate, self-financing is based on multiple activities. Briefly, it encompasses scientific projects and industry projects. First, members of the non-profit parts or the science lab write grant applications for supranational, national and regional funds. More recently the organization started cooperating with the European Commission and now organizes an international prize for “innovative projects at the intersection of research and science, technology and arts” (webpage). Second, NRC also builds on industry cooperation and sponsorship. We found that each year a high number of industrial partners support projects and other activities of NRC. The press, for example, reports on more than 150 partners of NRC during 2014—a huge amount of collaborations that support NRC’s activities. Third, NRC has two specialized units that foster industry-related projects. The science lab engages in basic and applied research and joint developmental projects with companies. Cooperation includes long term relationships with firms from diverse industries like automotive, information technologies, or the chemical industries but also short-term contractual research. In addition the sales unit’s main goal is to increase the self-financing rate of NRC. Thus, this unit is dedicated to offer products and services at the market place. It attempts to exploit the tremendous technological know-how of NRC and to gain profits. These profits are used to cross-finance the non-profit parts of the organization. Fourth, also the non-profit parts of the organization earn financial returns via ticket sales, renting or sponsorship.

Table 3 shows the different forms of financing and according projects that can be placed on a continuum from non-profit to for-profit. As we will discuss in the next section this strategy of multiple-party funding offers opportunities but also bears serious threats for the organization.

4.2 Context and consequences of public funding

Public funding ensures NRC’s continued existence for more than 30 years. Political decision makers consistently stuck with the idea of NRC and its vision. For example, in 1987 the mayor writes: “This year the anchoring of NRC in the City’s cultural activities was finally made possible. […] With this, the City clearly adheres to the ideas of innovation and experiments, even if this necessarily fosters contradiction, criticism or even refusal.” This indicates a clear commitment of the policy makers, even in difficult times. They always have been seeing something visionary in NRC’s activities that could support the image-shift the City aimed at. For NRC this support built the limited, but stable, financial basis to pushing their artistic and scientific ideas forward.

Public funding creates dependency. More recently the City suffered from a serious financial crisis. It thus cut its financial support for NRC up to 25%. “Unfortunately, during the last two, three years we were hit by massive funding cuts. At least 25% compared to 2011.” (financial director) NRC had to accept this new situation and to find ways on how to deal with it. The non-profit parts especially are highly dependent on public funding. They had to cut back on their activities or planned projects, which was very risky: “NRC is known for its innovativeness. People expect us to regularly show new exhibitions. […] Failing on this damages our image.” (unit head). Cuts in public funding thus can cause serious troubles and affect the organization as a whole. More than 20% of the personnel had to be dismissed, which also led to fundamental restructuring processes in the organization.

Public ownership fostered the establishment of more effective governance structures as well as increases in reports. Public ownership fostered the establishment of more effective governance structures. Interview partners report on increasingly more financial reports and demands for more effective structures. These pressures increased when NRC faced serious financial troubles. Newspapers reported on a fundamental financial crisis of NRC. So, politics insisted on a more business-like attitude. “The problems have to be solved quickly!” stated, one of the political board members. Today NRC is organized like a for-profit organization. The different units operate like profit-centers that are fully responsible for their activities. The financial director considers this as particularly important, as “each of our activities also includes an economic aspect.” Additionally, the organization has to rely on professional governance tools that allow for timely strategic or operational adjustments if necessary.

Public funding demands for taking political interests seriously. Since its beginnings NRC built on the support of politicians. Politicians pursue their own interests. Attempts to be re-elected often mean decisions are based on short-term and local interests. Archival data reveal that the City’s decision to support the initiating event was mainly influenced by the perception that this event could positively affect the City’s cultural image. The tremendous interest of the local public at the first event was additionally a convincing argument to further support this “experiment”. Thus, “convincing responsible politicians that a project like NRC could substantially support their interests was one of the key factors for the organization’s continued existence.” (member of the founding team) In addition we found that some of the organization’s strategic decisions were made to support these political interests. As NRC gained more and more international attraction it concurrently attempted to fulfill the needs of the local public.

4.3 Context and consequences of self-financing

In addition to direct financial support from governmental institutions NRC strives for high rates of self-financing. The main sources for this are public grants and industry projects (see Table 3).

Self-financing ensures autonomy. NRC pursues an artistic, societal and scientific vision. To ensure its artistic and scientific freedom and autonomy NRC has always achieved a profit, currently up to 60% of the annual budget. The artistic director emphasizes: “And that’s why I consider this economic thinking as so important. It is the key for a real independent and self-directed way of working and artistic programming. […] This secures autonomy! Because it enables us to earn money, built on our own productivity.” Cultural and scientific projects do not just rely on funds from the public owner. Instead, self-financing enables the organization to realize the projects that they consider as important. It helps to escape the restrictions associated with public funding. One of the members of the founding team, for example, describes that awarding the international prize for media arts was only possible due to the financial support of a large sponsor. Although it was then hard work to establish this prize, industry cooperation allowed NRC to stimulate its development into an internationally unique organization. Public funds would have never had the capacity to provide such financial resources.

Self-financing enables organizational persistence. As a response to the dramatic funding cuts in recent years NRC increased its self-financing activities. Interview partners report on an increase of grant applications within the non-profit parts and intensified attempts to acquire large, international sponsors. The number of external exhibitions that were sold internationally rose substantially. This also increased pressures for efficient processes of organizing. “A key quality feature of NRC is that none of the, let’s say 100, external exhibitions is the same. […] The challenge now is to find an efficient way of organizing to make this economically efficient. Like, … finding a standard operating procedure and just changing the content”, explains one of the unit heads. Additionally, the science lab intensified its industry cooperation and we recognize a general increase of industry projects. Finally, the sales unit was founded. This unit is dedicated to offer products and services at the market place and to sell them to paying customers. It attempts to exploit the tremendous technological know how of NRC and to gain profits. Balance reports and financial accounts show that due to these activities NRC was able to effectively respond to the financial challenges caused by the dramatic cuts in public funding.

Self-financing ties up developmental resources. Large industry projects are one of the sources for gaining financial profits. Members of the TMT and experts run these science lab projects. Their specific know-how is internationally unique and especially large companies refer to NRC to boost their own developmental activities. One of the unit heads outlined what makes NRC unique: “When we build new projects these are drafts of possible futures. What happens if technology is used in this or that way? What happens with society? What are the opportunities resulting from this?” These ways of approaching technology offer completely new perspectives for business firms and shape their innovation processes as well as the development of new products. However, when these experts from the science lab work for paying customers NRC lacks resources for their own developmental activities. One of the directors emphasized: “Overwhelming these five, six persons with [business] projects just to optimize financial profits means at the same time taking away the most important development resource for the organization itself.” Thus, striving for financial profits could threaten the organization’s development. In a similar vein, employees from the non-profit parts refer to the huge amount of time they have to invest when writing grant applications. Never knowing if they will succeed and if it would not have been better to invest their time for the development of cultural projects.

Self-financing threatens the organization’s diverse goals. NRC set high goals for its self-financing rate. Financial pressure is constantly there. “Everyone feels these financial pressures! […] That’s the point: We have to earn money.” (employee) Decisions, whether to pursue a project or not are often based on the financial benefit of the projects. Contractual research offers opportunities to acquire these financial resources. The science lab sells its particular competences to paying customers. Still, contractual research is short-term oriented and mainly pursues the customer’s interests. Pure developmental projects where nobody knows how the outcome could look like, are rare. Interview partners thus emphasize that high rates of self-financing can negatively affect the organization’s overall goals. “I did not experience such financial pressures in other artistic institutions. […] There they also acquired new employees for working on the projects. Still, the goal was to make it a really great project, with impact. And not to think about financial issues like we do.” (former employee).

Self-financing affects the commitment of employees. Public grants, as another source for organizational self-financing, are targeted towards individuals. These grants often finance the salaries of specific persons and support their particular projects. Research institutions, like for example the science lab, provide the formal, organizational framework to conduct the research projects. The respective researchers have to pay overhead costs. As interview partners admit, in case of publically funded research projects very often they “do not work for the organization, they work for their own.” (former employee) Thus, research institutions run risk of losing highly qualified employees if they lose attractiveness or when other institutions provide better opportunities. Additionally, self-financing via public grants raises the competitions among employees. One of the interview partners describes: “And there are additional dynamics. These consider questions like ‘Who is allowed to write grant applications?’ ‘Which research questions are considered interesting and thus worth to be pursued?’ and so on.” (employee) A lack of a clear strategy or guidelines creates uncertainty and can lead to misunderstandings and frustration.

4.4 Tensions resulting from multiple-party funding

As our analysis reveals both public funding and self-financing offer opportunities and expose threats concurrently. NRC combines multiple sources for financing and manages them via different projects.

The core intention of NRC is to achieve a societal, artistic and scientific impact. Cultural, scientific and business projects represent different forms of activities that support these goals. And although each of the project types follows a distinct, dominant logic the core idea of pursuing a societal mission has to be integrated in whatever project that is run. The quote of a project leader in the sales unit represents this core idea that we found throughout the organization. “We are not free in deciding which projects to engage in—even if we might earn much money. We have to select our projects carefully and always check if they represent what NRC is and does.” (project leader).

Cultural projects are targeted towards society and strive for a societal and artistic impact. They are mainly located within the non-profit parts of the organization. Financial resources are primarily provided by the public owner, as well as local and national governments. Thus, these projects follow a societal logic bound to overall political interests. Scientific (and partly artistic) projects address an academic audience, strive for scientific impact and encompass basic and applied research. At NRC it is mainly the science lab that engages in these projects. National, international and EU-funds build the main financial sources for this. Scientific (and partly artistic) projects follow mainly a scientific, research logic. Business projects are targeted towards business partners. They follow economic goals and strive for developing applied resp. practical knowledge. Sales and the science lab engage in business projects that are mainly run with national and (large) international firms. The dominant logic behind these projects is business and innovation (driven by the interests of the industry partners).

This approach enables the organization to respond to increasing financial pressures and to ensure the pursuit of its vision by achieving societal, artistic and scientific goals. Still, it is also a main source of tensions. Table 4 summarizes the consequences related to splitting different demands by setting up different projects. We identified core tensions accompanied with questions of financing.

Tensions that emerge from being embedded in multiple logics and being confronted with multiple stakeholder demands. The commitment and the financial support of the public owner even in difficult times ensured NRC’s continued existence from its beginnings. However, public funding also demands taking the politician’s interests seriously. Interview partners refer to several serious struggles in NRC’s history between politics and NRC’s top management team (TMT) or even within the TMT. These conflicts influenced recruiting decisions especially in higher management positions, decisions with regard to the organization’s strategic direction or the implementation of more effective governance structures. The TMT is aware of these tensions: “We are an artistic and cultural organization, municipally owned and thus embedded in a politically guided public governance structure that needs to be managed as a business.” Public funding, in this sense, builds the solid ground for NRC’s persistence while simultaneously affecting its strategic direction. In a similar vein, high rates of self-financing contribute to stable organizational persistence. They enable NRC to respond to financial pressures and to consequently pursue projects that the organization considers as important. Interview data reveal that some of the hallmarks in NRC’s development could only be achieved due to external financial sources. Still, self-financing also fosters the emergence of tensions. While selling services on the market place, engaging in contractual research or writing grant applications generates financial resources that can be invested in interesting and important cultural and scientific projects, they also bind resources and may threaten the organization’s image.

Tensions that emerge from pursuing multiple goals concurrently. In a particular sense, public funding enables autonomy especially with regard to artistic, societal and new research topics. The home city, for example, provided public financial resources for the initiating event but did not intervene with regard to societal, cultural or scientific content. Thus, public funding created an opportunity for a core team of visionary thinkers to transcend contemporary perspectives. Still, public funding also creates dependency. The scope of cultural activities is restricted to the amount of public payments. In NRC’s history, we identified several phases where especially the non-profit parts struggle with the restrictions of public funding and put extraordinary effort in sustaining their cultural projects. When the mayor cut public funding dramatically due to the financial crisis NRC had to accept the situation and to find ways on how to face these challenges. One of the directors admits: “We could not do anything against it. We had just to accept the new situation and to act accordingly.” So, while public funding creates autonomy it simultaneously fosters dependency. Self-financing is a way to escape these restrictions. As interview partners state, grants, industry-related research, business projects or sponsorship secured NRC’s autonomy. Profits from these activities are used to cross-finance the non-profit parts and to pursue many of the cultural and scientific projects that best support NRC’s vision. However, exactly these sources for self-financing might eventually threaten the organization’s societal and artistic goals. “Industry-related projects and applied research are short-term oriented. They are mainly directed towards the goals of the partnering firms. […] It is like selling our know how and gaining profit for this.” Especially when financial pressures increase for-profit projects are often preferred at the expense of developmental projects. While self-financing supports autonomy with regards to contents it simultaneously restricts this autonomy when resources are scarce.

5 Managing the tensions of multiple-party funding

Multiple-party funding creates tensions that need to be managed. Organizational sustainability depends on the organization’s continuous efforts to accept and meet multiple, divergent demands (Smith and Lewis 2011; Lewis 2000; Cameron 1986). A paradox perspective argues that long-term success is rooted in embracing paradoxes (Lüscher and Lewis 2008; Smith and Lewis 2011). Strategic responses—as one-way how to respond to paradox (Lewis and Smith 2014)—attempt to engage the competing forces. They encompass accepting strategies, thereby advocating embracing and confronting paradox and resolution strategies, including splitting and integrating.

5.1 Embracing tensions

Using language for surfacing tensions and appreciating contradictions. NRC acts in a variety of fields and addresses the needs of many divergent stakeholders: national and international artists and scientists, the local and international public, educational and research institutions, cultural institutions and private companies. Addressing the different needs and performing on high levels is challenging as the demands often compete or are even in opposition to each other. They therefore can also lead to tensions. NRC positions itself at the intersection of different worlds, thereby accepting the influence of multiple stakeholder interests. Our results show that embracing tensions (Smith and Lewis 2011; Lewis 2000; Cameron 1986) and even using them for securing their own position seemingly serves as one of the guiding principles for NRC long-term survival and sustainability.

All of our findings point to interrelations with different fields and contradictory demands that according to the literature is expected as being perceived as tension, ambiguity, conflict, or at least as being difficult. However, interestingly our respondents rarely connoted this as negative even when they described the situations as challenging. Instead they were labeled as important preconditions or just given facts. When respondents report on situations in the context of paradoxical tensions they often describe “both sides of the coin”, e.g. explaining the negative aspects in the first sentences, subsequently followed by a description of the positive aspects of a given situation or vice versa. Respondents, for example, state: “Striving for multiple goals is challenging but necessary.” (Project leader), “Public funding is our core financial resource; still, a high rate of self-financing offers freedom and autonomy.” (TMT) or “Public funding provides the basis for the non-profit parts of the organization; still, this creates dependency.” (Unit head) Thereby the organization uncovers each of the (seemingly) opposing poles, valuing their distinct nature and highlighting that each of which is equally important and necessary (Poole and van de Ven 1989). Using language therefore seems to be a helpful way to surface possible contradictions and to reframe (Bartunek and Rynes 2014) them by surfacing the positive sides of contradictions concurrently. Acceptance of tensions and paradox by embracing them allows for dealing with them in a more sophisticated way. Working through tensions (Lüscher and Lewis 2008) is a precondition for paradoxical resolution strategies “via iterating responses of splitting and integration” (Smith and Lewis 2011).

5.2 Modes of splitting

Multiple project structures enable focus and specialization. Structural separation enables specialization and helps to maximize the distinct advantages of different activities (Kauppila 2010). The importance of creating dual structures is emphasized especially by literature on ambidexterity. It suggests dual structures could include the creation of specific functions or the assignment of employees to different groups or tasks (O’Reilly and Tushman 2011; Smith and Tushman 2005).

On a strategic level separating senior managers tasks and splitting between responsibilities as regards content and financial issues is one of NRC’s approaches, which is not free of conflict. In addition, NRC uses different forms of financing-projects to address its various stakeholder interests and pursue its multiple goals.

One of the enduring struggles of NRC is the permanent competition for scarce resources. NRCs approach of addressing these tensions is managing the different demands through separate projects. These projects allow NRC to align their overall vision for the whole organization. At the same time, the flexible project structure enables high adaptability to reconfigure activities quickly. This helps to meet financial goals and innovative ideas and rigorous research output simultaneously. With regard to the different projects we recognize that they pursue different goals, that all are relevant for the persistence of the organization. Still, they are all bound to the core artistic and societal impact NRC seeks to achieve. Our results indicate that for the sake of specialization and concentration a clear differentiation resp. separation between the various types of projects is important.

5.3 Integration mechanisms

An overall vision and valuing interdependencies support social integration mechanisms. Since its beginnings NRC seeks out to integrate different stakeholder interests and to pursue different goals in order to achieve its overall vision. NRC builds on the conviction that each of the perspectives and positions is equally valuable and accepts related tensions. Language serves as a powerful means to integrate the distinct perspectives on an overall organizational level and to simultaneously acknowledge the idiosyncrasy of the single elements (Poole and van de Ven 1989). Furthermore the management strongly emphasizes synergies by focusing on the positive sides of the interrelation of the projects.

The use of integrative metaphors such as “a highly sophisticated system” or “gear wheels that interlock” acknowledges the existence and idiosyncrasy of every single element, yet surfacing their strong interrelation. Every project that is run and every activity that is taken, has to support the basic idea of NRCs overall vision. Such use of language builds a shared frame of reference (Garaus et al. 2016; Güttel et al. 2012) and a common mindset (O’Reilly and Chatman 1996) as important social integration mechanism.

Managing the project portfolio as overall integrative mechanism. Tight coordination of top management plays a decisive role for integrating specialized and separated units, projects or tasks (Smith and Tushman 2005). NRC’s senior management decides on the resource allocation regarding the various projects by setting strategic guidelines, such as research programs or NRCs vision and mission. One of the CEO’s approaches to maintain balance between the different projects is to monitor the overall project portfolio. To keep governmental funding, NRC needs to constantly legitimate its existence by focusing on repute and image of the city.

Developing multiple-competent capabilities. Kieser and Leiner (2009) argue collaborative projects can help people develop bi-competent capabilities. Given the specific characteristics of different forms of financing in the case of NRC these capabilities might be even multi-competent. Various projects demand employees to engage in diverse projects and to switch between different learning domains. These projects pursue different goals, address different target groups, and follow different logics. On the one hand, this puts pressure on employees that are involved in different projects. On the other hand, it allows for developing multi-competent capabilities. Employees are able to speak multiple languages: the one of practice, the one of art, the one of science and thereby bridge different contexts. As a consequence, a supportive context in which employees are able to wear “two hats” and make judgments about how to allocate their time resources are of utmost importance (Ambos et al. 2008; Gibson and Birkinshaw 2004).

6 Consequences for universities, business schools and academic research

The necessity for European universities to engage in third-party funding seems to be inevitable. Since the financial pressure for European universities is expected to increase instead of diminishing, tensions that emerge from pursuing multiple goals and addressing multiple funding sources concurrently must be accepted as persistent parts of the organization (Ambos et al. 2008; Smith and Lewis 2011). As paradox studies suggest, acceptance of ambiguities and contradictions is an important precondition for dealing with tensions and paradox in a more sophisticated way. For universities, it therefore seems to be important to shift the question from “Should universities and business schools collaborate with practitioners?” to questions like “How could we shape the process of collaborating with practitioners?” since this process bears some risks but also offers opportunities.

Establishing a self-concept that integrates plurality. Since its beginning, NRC relies on different forms of self-financing. The organization considers itself as an “art business” thereby integrating its core artistic goals and economic rationales (Jäger and Beyes 2010). For universities this might serve as guiding example of how the idea of self-financing might successfully be integrated in their self-concepts. Instead of focusing on the threats of third-party funding universities need a switch in perspective and to take the responsibilities they are given, also with regard to providing pluralism of science (cf. e.g. Ghoshal 2005). In addition, a diversified funding base allows academic institutions to leave their role as victims and to escape the demand-response imbalance (Clark 1998, 2001). Putting the idea of the “entrepreneurial” university into practice empowers universities to pursue their own strategies, to make self-reliant decisions and to strengthen their autonomy (Clark 1998, 2001; Etzkowitz 2003).

Strategic positioning in a multi-stakeholder environment. NRC operates within a variety of different fields: They work with political and governmental institutions; they cooperate with science and education: universities, as well as private research institutions, schools, and other educational institutions; they collaborate with associations and networks all over the world but also with different companies. Our results support the argument that organizations sometimes strategically need to maintain competing aims and that they have to prevent any resolution that favours just one side. In such cases, organizations can utilize competing environmental demands from stakeholders to create or maintain the co-existence of paradoxical aims. NRC deliberately utilizes competing demands from their heterogeneous environment for legitimizing the simultaneous accomplishment of contradictory aims and tasks. Furthermore, they emphasize the equivalent existence of different objectives by using metaphors to prevent that the organization might drift towards only one side while ignoring another. For universities this might provide an opportunity to leave narrow, one-sided paths that might result in being locked into academic research trajectories (Ambos et al. 2008) and thereby support the plurality of scholarships (Ghoshal 2005). Too one-sided, narrow specialization can result in the loss of capacity to communicate with other systems, which as a consequence can lead to tensions and conflict (Kieser and Leiner 2009).

Multiple-structures allow for multi-focus and specialization concurrently. Ambos et al. (2008) show that it is possible to achieve dual goals at the organizational level “through the combination of excellence in scientific research and the provision of a dual structure to facilitate the commercialization of academic inventions.” (p. 1441) Similar to what we see in the case of NRC structural separation for universities via projects would be an option for enabling focus and specialization on the one hand, and pursuing both basic and applied research concurrently. In balancing these projects, however, it is important for universities not to lose sight of its core duty. Given that for academic research distance to practice is important a too close interrelation of different fields can threaten universities’ raison d’être. As Kieser and Leiner (2009, p. 528) state, if science loses its distance to its research objects “it would no longer be able to generate knowledge that is different in principle from the knowledge of competent practitioners.” Academic research with its core aim of producing scientific knowledge that should enable critical reflections on current practice is contradictory to producing directly applicable practical solutions for business. Engagement in industry-cooperation can therefore pose serious challenges on universities.

Summarizing, this study contributes to contemporary literature as follows. First, this study extends the ongoing discussion of the entrepreneurial university. The case of NRC shows how multiple-party funding fosters autonomy and consequently enables the organization to pursue its core societal goals. This is one of Clark’s (1998, 2001) key arguments when he introduces the idea of the entrepreneurial university. In particular he advocates a diversified funding base building on (a) governmental support, (b) financing from research funds and (c) third-stream income including university-industry collaborations. NRC combines exactly these different forms of financing and thus might work as an empirical example for Clark’s (1998, 2001) initial considerations.

Second, this case reveals the difficulties associated with multiple-party funding but also shows approaches for the management of universities and business schools. We use paradox theory (Smith and Lewis 2011, Lewis and Smith 2014) to elaborate on these difficulties in more detail, to shed light on the underlying mechanisms and to discuss management strategies for successfully dealing with the challenges. Building on multiple sources of funding fosters tensions. These tensions emerge from combining multiple, different sometimes contradictory logics and stakeholder demands as well from pursuing multiple goals. Paradox theory shows that proactively approaching these tensions ensures organizational success and sustainability. Strategies like embracing tensions, splitting and integrating (Smith and Lewis 2011; Lewis 2000; Poole and Van de Ven 1989; Cameron 1986) ensure the successful management of a diversified funding base (Clark 1998, 2001).

Third, we consider our results of practical relevance for universities and non-university R&D-focused organizations, which face the challenges of multiple-party funding. Our practical implications might also be relevant for any other firm that faces the challenge to pursue diverging goals simultaneously. These different demands can be balanced strategically by determining strategic guidelines such as research programs and giving autonomy to divisions and sub-units to quickly establish projects with a specialized focus. Companies can strengthen the efficiency of projects by defining concrete practices to absorb external knowledge from their environment. They can enhance the efficiency of the processes by developing personnel, establishing access to databases and reports, and manage networks with partners in relevant environments. Finally, establishing social integration mechanisms, supporting a shared frame of reference and sharing a common culture reintegrates the knowledge from temporarily separated projects.

7 Conclusion

To conclude, the results of our study reveal core tensions that result from multiple-party funding and identify different approaches of managing these tensions. By integrating a paradox perspective we systematically discuss opportunities for universities to establish and manage multiple-party funded research that contributes to both, excellence in research and organizational sustainability. Thus, instead of focusing on one specific form of third-party funding, such as university-industry collaborations, our study contributes to refining our understanding on the overall management of multiple-sources of funding. We chose the case for reasons of similarities with regards to the process and the context. NRCs approaches of dealing with tensions that emerge from multiple-party funding are especially based on their self-concept, the consistent alignment with their overall vision, which also helps them use political interest for their own sake instead of being put under pressure of policy justification. We argue universities that currently face the challenges of increased financial pressure can learn from of practices of embracing, separating and integrating paradoxical tension. However, since our study was not conducted in a university context and because of its specifics, the results are not generalizable to all universities. As a further limitation, our study discusses core tensions associated with multiple-party financing. However, there are further tensions associated with NRCs complex processes of organizing and its various forms of financing. For further directions, it would be worth to explore various tensions that emerge from multiple-party funding in different contexts. Comparative studies of different European university systems especially could offer interesting insights in this regard.

References

Adler PS, Goldoftas B, Levine D (1999) Flexibility versus efficiency? A case study of model changeovers in the Toyota production system. Organ Sci 10:43–68

Albers S (2015) What drives publication productivity in German business faculties? Schmalenbach Bus Rev 67(1):6–33

Ambos TC, Mäkelä K, Birkinshaw J, D’Este P (2008) When does university research get commercialized? Creating ambidexterity in research institutions. J Manag Stud 45(8):1424–1447

Andriopoulos C, Lewis MW (2009) Exploitation–exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: managing paradoxes of innovation. Organ Sci 20(4):696–717

Ash MG (2006) Bachelor of what, master for whom? The Humboldt myth and historical transformation of higher education in German-speaking Europe and the US. Eur J Educ 41(2):245–267

AQ Austria – Agentur für Qualitätssicherung und Akkreditierung Austria (2016) Qualitätssicherung an österreichischen Hochschulen – Eine Bestandsaufnahme. facultas, Wien

Balser D, McClusky J (2005) Managing stakeholder relationships and nonprofit organization effectiveness. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 15(3):295–315

Bartunek JM, Rynes SL (2014) Academics and Practitioners are alike and unlike: the paradoxes of academic-practitioner relationships. J Manag 40(5):1181–1201

Benner MJ, Tushman ML (2003) Exploration, exploitation, and process management: the productivity dilemma revisited. Acad Manag Rev 28(2):238–256

Bennis WG, O’Toole J (2005) How business schools lost their way. Harv Bus Rev 83(5):96–104

Blaschke S, Frost J, Hattke F (2014) Towards a micro foundation of leadership, governance, and management in universities. High Educ J 68:711–732

Bmwf (2016). http://wissenschaft.bmwfw.gv.at/bmwfw/forschung/national/forschung-in-oesterreich/partner-institutionen/fwf-der-wissenschaftsfonds/. Accessed 11 Jan 2016

Bonaccorsi A, Secondi L, Setteducati E, Ancaiani A (2014) Participation and commitment in third-party research funding: evidence from Italian universities. J Technol Transf 39(2):169–198

Brett J (2000) Competition and collegiality. In: Coady T (ed) Why universities matter. A conversation about values, means and directions. Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards, pp 144–155

Cameron KS (1986) Effectiveness as paradox: consensus and conflict in conceptions of organizational effectiveness. Manag Sci 32:539–553

Cameron KS, Quinn RE (1988) Organizational paradox and transformation. In: Quinn RE, Cameron KS (eds) Paradox and transformation. Toward a theory of change in organizations and management. Ballinger Publishing Company, Cambridge, pp 1–18

Chisolm LB (1995) Accountability of nonprofit organizations and those who control them: the legal framework. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 6:141–156

Clark BR (1998) Creating entrepreneurial universities: organizational pathways of transformation. International Association of Universities and Elsevier Science, Paris

Clark BR (2001) The entrepreneurial university. New foundations for collegiality, autonomy, and achievement. High Educ Manag 13(2):9–24

Clegg SR, Cunha JV, Cunha MP (2002) Management paradoxes: a relational view. Hum Relat 55(5):483–503

Cresswell JW (2007) Qualitative inquiry and research design, 2nd edn. Sage, London

D’Este P, Perkmann M (2011) Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. J Technol Transf 36(3):316–339

Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME (2007) Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad Manag J 50(1):25–32

Etzkowitz H (2003) Research groups as ‘quasi-firms’: the invention of the entrepreneurial university. Res Policy 32:109–121

EUA – European University Association (2015) EUA Public Funding Observatory. http://www.eua.be. Accessed 11 Jan 2016

Flick U (2009) An introduction to qualitative research, 4th edn. Sage, London

Garaus C, Güttel WH, Konlechner S, Koprax I, Lackner H, Link K, Müller B (2016) Bridging knowledge in ambidextrous HRM systems: empirical evidence from hidden champions. Int J Hum Resour Manag 27(3):355–381

Geuna A (2001) The changing rationale for European university research funding: are there negative unintended consequences? J Econ Issues 35:607–632

Ghoshal S (2005) Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Acad Manag Learn Educ 4(1):75–91

Gibbs G (2007) Analyzing qualitative data. In: Flick U (ed) The Sage qualitative research kit. Sage, London

Gibson CB, Birkinshaw J (2004) The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Acad Manag J 47(2):209–226

Gioia DA, Corley KG, Hamilton AL (2012) Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ Res Methods 16(1):15–31

Golden-Biddle K, Rao H (1997) Breaches in the boardroom: organizational identity and conflicts of commitment in a nonprofit organization. Organ Sci 8(6):593–611

Göransson B, Brundenius C (2011) Background and introduction. In: Göransson B, Brundenius C (eds) Universities in transition. The changing role and challenges for academic institutions. Springer, New York

Güttel WH, Konlechner S, Müller B, Trede JK, Lehrer M (2012) Facilitating ambidexterity in replicator organizations: artifacts in their role as routine-re-creators. Schmalenbach Bus Rev 64:187–203

Heckscher C, Martin-Rios C (2013) Looking back, moving forward: toward collaborative universities. J Manag Inq 22:136–139

Hodgkinson V, Painter A (2003) Third sector research in international perspective: the role of ISTR. Volunt Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 14(1):1–14

Hofstadter DR (1979) Gödel, Escher, Bach: An eternal golden braid. Vintage Books, New York

Isenberg D (1984) How senior managers think. Harv Bus Rev 62(November–December):81–90

Jäger U, Beyes T (2010) Strategizing in NPOs: A case study on the practice of organizational change between social mission and economic rationale. Volunt Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 21:82–100

Jarzabkowski P, Lê JK, Van de Ven AH (2013) Responding to competing strategic demands: how organizing, belonging, and performing paradoxes coevolve. Strat Organ 11(3):245–280

Jay J (2013) Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Acad Manag J 56(1):137–159

Jones C (2014) Dirty money. J Acad Ethics 12(3):191–2017

Kauppila O-P (2010) Creating ambidexterity by integrating and balancing structurally separate interorganizational partnerships. Strat Organ 8:283–312

Kearns KP (1994) The strategic management of accountability in nonprofit organizations: an analytical framework. Public Adm Rev 54(2):185–192

Kieser A, Leiner L (2009) Why the rigour-relevance gap in management research is unbridgeable. J Manag Stud 46(3):516–533

Kieser A, Leiner L (2012) Collaborate with practitioners but beware of collaborative research. J Manag Inq 21:14–28

Kreiner GE, Hollensbe EC, Sheep ML (2006) Where is the “me” among the “we”? Identity work and the search for optimal balance. Acad Manag J 49(5):1031–1057

Lenzen D (2015) University of the world. A case for a world university system. Springer, Hamburg

Lewis MW (2000) Exploring paradox: toward a more comprehensive guide. Acad Manag Rev 25(4):760–776

Lewis MW, Smith WK (2014) Paradox as a metatheoretical perspective: sharpening the focus and widening the scope. J Appl Behav Sci 50(2):127–149

Lüscher LS, Lewis MW (2008) Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: working through paradox. Acad Manag J 51(2):221–240

Lüscher LS, Lewis MW, Ingram A (2006) The social construction of organizational change paradoxes. J Organ Change Manag 19(4):491–502

Malone DM (2011) Forword. In: Göransson B, Brundenius C (eds) Universities in transition. The changing role and challenges for academic institutions. Springer, New York

March JG (1991) Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ Sci 2(1):71–87

Miles R, Huberman A (1994) Qualitative data analysis: a sourcebook of new methods. Sage, Beverly Hills

Mintzberg H (2004) Managers, not MBAs: a hard look at the soft practice of managing and management development. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco

Mintzberg H, Simons R, Basau, K (2002) Beyond selfishness. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 44(1):67–74

O’Reilly CA, Chatman JA (1996) Culture as social control: corporations, cults, and commitment. Res Organ Behav 18:157–200

O’Reilly CA, Tushman M (2008) Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res Organ Behav 28:185–206

O’Reilly CA, Tushman ML (2011) Organizational ambidexterity in action: how managers explore and exploit. Calif Manag Rev 53:5–22

OECD (2016) OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 2016. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-deu-2016-en

OECD (2017) OECD economic surveys: Austria 2017. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-aut-2017-en

Orr D, Jaeger M, Schwarzenberger A (2009) Performance-based funding as an instrument of competition in German Higher Education. In: Malcolm T, Ka Ho M, Huisman J, Morphew CC (eds) The Routledge international handbook of higher education. Routledge, New York

Patton MQ (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Poole MS, Van de Ven AH (1989) Using paradox to build management and organizational theory. Acad Manag Rev 14:562–578

Quinn RE (1988) Beyond rational management. Mastering the paradoxes and competing demands of high performance. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Salamon LM (1999) The nonprofit sector at a crossroads: the case of America. Volunt Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 10(1):5–23

Salter AJ, Martin BR (2001) The economic benefits of publicly funded basic research: a critical review. Res Policy 30(3):509–532

Schmoch U (2011) Germany: The role of universities in the learning economy. In: Göransson B, Brundenius C (eds) Universities in transition. The changing role and challenges for academic institutions. Springer, New York

Scholz M, Fink M, Down S, Hatak I (2016) Special issue call for papers. He who pays the piper calls the tune? Potentials and threats of third party funding of academic research in Europe. Rev Manag Sci