Abstract

Intrapreneurship as a sub-field of entrepreneurship has increased in importance. Due to the crucial role of entrepreneurial employees with regard to innovation and competitive advantage, research has increased and various concepts have emerged. Despite the growing interest in the field, intrapreneurship is still lacking a clear classification of the related concepts as research has thus far been based on diverse theoretical approaches. Indeed, contributions in the field are fragmented, using various definitions. There is no systematic review providing an overview of the field. By distinguishing between corporate entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial orientation and intrapreneurship, this paper clearly positions intrapreneurship as individual-level concept. Most prior research has been done at the organizational level, focusing on concepts such as corporate entrepreneurship, but research concentrating on individual intrapreneurial employees is rare. Therefore, this paper closes the gap by performing a systematic literature review and using a narrow focus to present the current state of research with regard to the individual-level perspective on intrapreneurship. The results of the review make it possible to identify five different research streams based on the analytical levels applied. The research streams examined used various lenses and cover business, technological and academic contexts. In a final step, the findings and possible research agendas are integrated in a model that serves as the basis for future research initiatives. Hence the paper offers the possibility of a clearer justification for future research and is a first step towards a holistic research model related to intrapreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurship in existing organizations has gained relevance in research as well as in practice. Due to the increasingly turbulent and competitive economic environment, firms have been looking for ways of managing innovation and generating competitive advantage. In this regard, entrepreneurial employees have been placed at the centre, as it has been emphasized that innovative employee behaviour leads to firm growth and strategic renewal (Veenker et al. 2008). Based on this assumption, various studies have been developed, focusing on different perspectives (individual-, team- and organizational level) and diverse theoretical foundations. The outcome of this is a new sub-field in entrepreneurship research, called intrapreneurship (Antoncic and Hisrich 2003). Due to the lack of a consistent definition of the concept of intrapreneurship (Åmo and Kolvereid 2005; Christensen 2005; Menzel et al. 2007), as well as different theoretical perspectives, intrapreneurship is a broad concept addressed in various research areas.

In this context, intrapreneurship is an emerging field in research and entrepreneurial employees especially and their skills and competencies gain in importance. Human capital plays a significant role when it comes to the success of ventures (e.g. Parker 2011). Intrapreneurs, defined as entrepreneurial-thinking people within existing firms, are crucial as they think across the boundaries of organizational units (Pinchot 1985). Therefore, these intrapreneurial employees are the foundation for innovation and the subsequent competitive advantage of firms (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2013).

Depending on the varying theoretical approaches, related concepts such as entrepreneurial orientation (Anderson and Covin 2014; Covin and Wales 2012), corporate entrepreneurship (Dess et al. 2003; Ireland et al. 2009) and corporate venturing (Antoncic and Hisrich 2003) have emerged. Moreover, similar but nevertheless different concepts and synonyms have developed, leading to further confusion in the field of intrapreneurship (e.g. Edú Valsania et al. 2016).

Responding to the need for clarification of the intrapreneurship concept, this paper seeks to examine the emphasis in intrapreneurship research and provides an overview of relevant issues in the field. Antoncic and Hisrich (2003) have already tried to clarify the concept of entrepreneurship within existing organizations and have provided an overview differentiating it from similar concepts, such as diversification strategy, organizational learning and organizational innovation. Furthermore, they point out the different dimensions of entrepreneurship and describe an eight-dimensional concept for organizational-level entrepreneurship. Although the authors used the term intrapreneurship in their research, their focus was not on the individual entrepreneurial employees but on organizations as a whole. The fact that their research was based on literature in the fields of management, innovation, strategy and entrepreneurial orientation further underlines that their focus was on the firm level than on the individual level.

In contrast, the aim of this paper is to identify the current research focus and possible research gaps in the intrapreneurship field at the individual level. Organizational-level concepts such as corporate entrepreneurship have already been investigated and results concerning the effects on a firm’s success are available. However, research providing an overview of individual-level intrapreneurship is rare, leading to the need for a research focus at this level. Based on the idea that entrepreneurial employees and their human capital are key to the success of ventures, a closer look is taken at intrapreneurs. To complement the organizational perspective of Antoncic and Hisrich (2003), the paper performs a systematic literature review and presents the findings focusing on intrapreneurship at the individual level. The results make it possible to present a research map and point out different research streams, as well as a future research agenda.

The paper accesses the field from the individual level perspective and hence contributes in several ways to the current development of the intrapreneurship field. As intrapreneurship is based on various theoretical concepts and perspectives, the contributions in the field are fragmented and employ various definitions (e.g. Turro et al. 2016). Despite the emergence of intrapreneurship research over recent years, there has as yet been no systematic review showing a detailed overview of the field. Therefore, this paper aims to close this research gap by performing a systematic literature review and presenting the current state of research. In addition, the paper answers the call for a clearer picture of the intrapreneurship concept by using a narrow focus and clearly distinguishing organizational- and individual-level concepts related to intrapreneurship. Hence, the contributions are threefold. First, as proposed by Åmo (2010), the paper distinguishes the concepts of corporate entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial orientation and intrapreneurship by mapping the literature. Furthermore, by clarifying the diverse concepts and their cutting points, it enables the identification of interesting gaps and shows the distinct position of intrapreneurship as an individual-level concept in the field. Second, with regard to current knowledge, it is the first paper to examine the intrapreneurship literature of the last few years by conducting a systematic literature review. By concentrating on the individual-level perspective, the review is restricted to a narrow focus which has been almost neglected in research as a separate area until now. The research performed in this paper takes a closer look at intrapreneurial individuals and therefore provides a knowledge base in this research field. Third, it contributes to the identification of the different streams in intrapreneurship research by shaping five different clusters dealing with various analytical levels. Therefore, the review tries to differentiate the various related emphases in individual-level intrapreneurship and points out paths for future holistic research approaches in this field.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section provides the theoretical foundations for this research and differentiates individual-level intrapreneurship from other concepts of entrepreneurship within firms. Section 3 introduces the review approach and the sample of journal articles included in the systematic literature review. Then, the findings of the research are presented by restructuring the intrapreneurship literature into different research streams in Sect. 4. In the next section, the paper discusses major findings and the research gaps identified. Furthermore, based on the review results, implications for theory are drawn and an outlook is provided on future research in the field of intrapreneurship. The paper concludes with implications for practice, as well as limitations.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Conceptualizing entrepreneurship within firms

Changes in the global economy have forced existing firms to put a particular focus on being innovative and moreover gaining competitive advantage (Kuratko and Audretsch 2013). Therefore, the research in the entrepreneurship field has clearly expanded by focusing not only on new venture creation and entrepreneurs, but also on the value of entrepreneurship within existing organizations (Antoncic and Hisrich 2003). The basic assumption is that innovative employee behaviour influences the firm’s performance by facilitating strategic renewal and access to new resources and skills (Dess et al. 2003; Kuratko and Audretsch 2013; Veenker et al. 2008). Although entrepreneurs also show innovative activities, research clearly distinguishes entrepreneurs from entrepreneurial employees. Entrepreneurial employees have been defined as intrapreneurs based on the work of Pinchot (1985). He introduced the term “intrapreneur” as a combination of “intracorporate” and “entrepreneur” and stated that intrapreneurs “closely resemble entrepreneurs […] who turn ideas into realities inside an organisation” (Pinchot and Pellman 1999, p. 16). Three main differences in particular are highlighted between intrapreneurs and entrepreneurs: intrapreneurs are able to use the existing resources of the company, they operate within organizations and they work within organizations that already have their own policies and bureaucracy (Baruah and Ward 2015; Camelo-Ordaz et al. 2012).

Shortly after its inception, research on entrepreneurship within firms emerged and focused on different levels of examination. Since this new field of research focuses on entrepreneurship in organizations, it is not surprising that much of the work conducted in the last decades has been established at the organizational level (Covin and Slevin 1991). Research based on this perspective examined organizational factors that influence employees’ entrepreneurial behaviour and the effect of this on company performance (Camelo-Ordaz et al. 2012; Menzel et al. 2007). Other research focused on the opposite perspective and was centred on the individual. Hence the individual characteristics of intrapreneurs (e.g. Martiarena 2013) as well as the determinants of employees’ entrepreneurial behaviour within firms have been examined (e.g. Douglas and Fitzsimmons 2013). Based on these two main perspectives, researchers indicated the need for a third perspective—the team-level perspective—in studies of employee entrepreneurship (Gapp and Fisher 2007). Research focusing on this level is scarce and only a few authors deal with intrapreneurial teams, e.g. their influence on the service and product development process (Gapp and Fisher 2007), or how intrapreneurial teams operate in various business contexts (Iacobucci and Rosa 2010).

As result of these three perspectives, different concepts dealing with entrepreneurship in firms were established. Approaches such as corporate entrepreneurship, corporate venturing, entrepreneurial orientation and intrapreneurship emerged, leading to some confusion as a clear classification is missing (Christensen 2005; Urbano and Turro 2013). Antoncic and Hisrich (2003) tried to provide an overview of the concepts and identified two streams of research at the organizational level. As a first stream, the authors pointed to the entrepreneurial orientation (EO) approach, which is based on the idea that innovation is a dimension of strategy making (Wales 2015). Hence, EO is defined as a firm-level construct (Anderson and Covin 2014), which is observable through EO on the part of the entire organization and a collection of organizational behaviours (Covin and Wales 2012). The construct developed through a series of studies and identifies an entrepreneurial firm as “one that engages in product-market innovation, undertakes somewhat risky ventures, and is first to come up with ‘proactive’ innovations” (Miller 1983, p. 771). Based on three dimensions—innovativeness, risk taking and proactiveness—a basic strategic orientation was established to measure the EO of firms (Bouchard and Basso 2011; Covin and Slevin 1991). Further research added two dimensions—autonomy and competitive aggressiveness—and established a five-dimensional construct (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Wales 2015). Also based on the organizational level is the second stream identified by Antoncic and Hisrich (2003), which points to the fostering of innovation and opportunity exploitation within a firm (Rigtering and Weitzel 2013). The so-called corporate entrepreneurship (CE) approach (e.g. Dess et al. 2003; Ireland et al. 2009) is similar to the EO approach, but distinguishes clearly two main streams. Corporate entrepreneurship can result either in corporate venturing (CV) and the creation of new business or the renewal of an existing organization. Later research also distinguishes these two characteristics and labels CV on the one hand and strategic entrepreneurship (dealing simultaneously with the topics of opportunity seeking and advantage seeking) on the other hand, under the banner of CE (Kuratko and Audretsch 2013).

Researchers in this specific field of entrepreneurship have increasingly differentiated between an organizational- and individual-level perspective (Moriano et al. 2014; Wakkee et al. 2010). Prior research has highlighted that CE and the intrapreneurship concept are closely linked, but are nevertheless not the same (Åmo 2010). In recent research, one characteristic in particular has gained recognition in differentiating between CE and intrapreneurship: CE can be seen as innovation process initiated from the top down within an organization, whereas intrapreneurship can be seen as bottom-up approach related to the intrapreneurial behaviour of employees (Åmo and Kolvereid 2005; Rigtering and Weitzel 2013; Sinha and Srivastava 2013). This clearly shows the different perspectives and the need for a clear classification between CE and intrapreneurship.

2.2 Intrapreneurship

As stated, the concepts of intrapreneurship and CE are closely linked to each other. Various researchers in this field have provided fruitful insights into how to differentiate the two approaches. The intrapreneurship concept is based on the idea that valuable human capital resides in entrepreneurial employees within existing organizations (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2013; Parker 2011). In particular, the characteristics of human capital, observable through intrapreneurial behaviour, provide a bridge between intrapreneurship and CE, either in terms of CE as a desired result from the firm’s top level or in terms of intrapreneurship as self-determined behaviour of employees (Åmo and Kolvereid 2005). It is also stated that CE does not automatically result in intrapreneurship behaviour as “the decision to opt for intrapreneurship remains an individual and personal decision” (Rigtering and Weitzel 2013, p. 342). Based on the aforementioned approaches and prior research, this paper tries to differentiate clearly the intrapreneurship concept as being at the individual level from the related concepts by mapping the diverging research approaches. Therefore CE and EO are categorized as organizational-level approaches and distinct from one another, as supposed by Antoncic and Hisrich (2003).

To sum up prior research and create an initial starting point for the systematic literature review, the paper maps the literature (Fig. 1) based on two dimensions: the level of perspective (organizational or individual) and the context of either an existing organization or new venture creation. Both EO and CE are categorized at the organizational level. Based on the assumption that these two constructs are related (Bouchard and Basso 2011) but not the same, they are separated. EO, mainly focusing on firms’ general strategic orientation towards entrepreneurship (Wales 2015), is mapped as approach for existing organizations. In contrast, the CE approach is divided into strategic entrepreneurship (referring to existing organizations) and CV (referring to new venture creation). This is also in line with prior work that identifies these two main streams of the CE construct (Antoncic and Hisrich 2003; Kuratko and Audretsch 2013).

The paper clearly categorizes intrapreneurship as an individual-level approach in existing organizations, supported by the definition of the intrapreneur as an employee who “recognizes opportunities and develops innovations from within an existing hierarchy” (Camelo-Ordaz et al. 2012, p. 3). Thus, it can be argued that intrapreneurial behaviour is not possible in CV, as it focuses on the creation of new businesses rather than developing innovations in existing ones. Rather, CV and new venture creation are associated with separation from the existing corporate firm and will lead to entrepreneurial tasks with higher risks and responsibilities, as well as the use of own resources. Hence, it is considered that CV will result in entrepreneurial behaviour at the individual level. Prior research has offered the insight that the organizational level (EO and CV) is closely linked to intrapreneurship. EO and CE can be seen as a breeding ground for intrapreneurship and vice versa. Both organizational antecedents and the individual self-determined behaviour of employees are necessary to enable intrapreneurial behaviour within established firms (Åmo and Kolvereid 2005).

Based on the literature map in Fig. 1, the paper is positioned in the field of intrapreneurship. As there is existing research on organizational concepts and also reviews on CE and EO are available (e.g. Dess et al. 2003; Kuratko and Audretsch 2013; Wales 2015), this paper focuses on the concept of intrapreneurship as an individual-level approach. By concentrating the review on this specific field, the paper sheds light on intrapreneurial individuals within organizations, constitutes a review of various research efforts on intrapreneurship and creates a knowledge base for future research directions.

3 Methodology

3.1 Review approach

To investigate the current state of research on individual-level intrapreneurship, a systematic literature review (SLR) was performed. This approach makes it possible to provide an overview of prior research in the field and a holistic perspective on the common knowledge base. Furthermore, the review contributes to the development of the intrapreneurship field by identifying different research streams and illustrating possible future research agendas. A systematic review approach is characterized by thoroughness and rigour, leading to legitimacy and the objectivity of results (Creswell 2009; Jesson et al. 2011; Tranfield et al. 2003). Based on this, the paper follows the suggestion of Tranfield et al. (2003) as a reference framework for conducting an SLR in the field of management and business. Therefore, the research was carried out by adopting the basic guidelines of these authors, dividing the SLR into the following steps: (1) planning the review, (2) conducting the review and (3) reporting and disseminating the review.

As Fig. 2 shows, in a first step the field of research was accessed by gaining an overview of relevant concepts in the field of intrapreneurship. In doing so, the current need for an SLR was identified, as different concepts emerged but a clear classification was missing. The aim was to identify relevant journal articles referring to intrapreneurship as an individual-level concept. The databases Ebsco, Emerald, ScienceDirect, Scopus and Web of Science were used. As intrapreneurship is a sub-field of entrepreneurship, in Ebsco four relevant entrepreneurship databases were selected: Business Source Premier, EconLit, Entrepreneurial Studies Source and PsycINFO. To be included in the review, the title, abstract or keywords of an article had to contain the search term “intrapreneur*”. As the focus of the SLR was on the individual level only, the search term was defined in a tight manner based on the definition of intrapreneurship. However, as already stated, researchers in the intrapreneurship field use different terms to describe intrapreneurship as a consistent definition is missing. To take this vagueness into account, the search term had to be included either in the title or abstract or keywords. Thus, research on intrapreneurship using for example the term “corporate entrepreneurship” in the title, but “intrapreneurship” in the abstract or keywords was also included in the search results. The use of an asterisk with the search term ensured that variations (e.g. intrapreneurs, intrapreneurial, intrapreneurship) were included in the results of the literature search. As further inclusion criteria, the type of publication was defined as a journal article, in English and published between 2005 and 2016.

Using this approach, an initial sample of 530 publications was identified. To ensure the inclusion of high-quality research, a quality assessment was performed and only those publications that were published in journals ranked in the Academic Journal Guide 2015 (AJG) of the Chartered Association of Business Schools or the VHB ranking 2015 (Jourqual 3) of the German Academic Association for Business Research were retained (N = 311). Usually only papers that meet specific ranking criteria (e.g. a ranking ≥ 2 in the AJG or ≥ C in VHB) are kept in review samples to provide a quality threshold. As a result of the narrow focus of the SLR, no further restriction concerning ranking criteria was defined. After the elimination of duplicates, further inclusion criteria were tested to ensure the quality threshold. As intrapreneurship is defined as a sub-field of entrepreneurship, enabling innovation within organizations, only those articles published in journals clustered in the relevant subject areas of AJG (Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management and Innovation) or VHB (Entrepreneurship and Technology, Innovation and Entrepreneurship) were included. Following this limitation, a sample of 58 articles was tested through an abstract-screening process. Based on the narrow definition of intrapreneurship as an individual-level concept, articles applying an organizational- or team-level view were excluded. The final sample of the SLR consisted of 32 articles dealing with intrapreneurship at the individual level.

As a first step, the articles were analysed with regard to their theoretical emphases and the research design applied. In the second step, the articles underwent a detailed content analysis. Relevant issues in the articles were coded and finally different research subjects were identified, synthesized and in a final step re-organized into research streams based on the analytical level applied.

3.2 An overview of intrapreneurship research

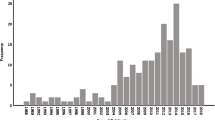

The sample of the SLR provides insight into the journal classes in which articles concerning intrapreneurship have been published. Different research areas were clustered based on the scope of the journals. The majority of articles appear in journals that focus on Business, Management and Strategy (N = 12), which is not surprising considering the theoretical foundations in management. The 32 articles in the review were published in 21 journals. The journal with the most publications in the thematic field is the International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, with eight articles in total (see Table 2 in the Appendix). In the period considered, 2005–2016, the number of articles dealing with the topic of intrapreneurship shows a growing trend. In particular, there is a peak in the year 2013, in which nine articles were published. The majority of the articles were published in the research areas of business and management, with only seven articles published in the research areas of innovation and technology.

Although the individual-level perspective was an inclusion criterion, some publications also considered the organizational-level of intrapreneurship (either EO or CE). Regarding the research subject, the sample articles examined factors predicting innovative behaviour, differences between entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship, individual and organizational antecedents of intrapreneurship activities, as well as management and leadership. Some authors focused on management themes, such as the role of middle-level managers (Kuratko et al. 2005), coaching by managers and its influence on employees’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Wakkee et al. 2010) and a processual perspective on intrapreneurship, which considers various actors at different management levels (Belousova and Gailly 2013). Other research has been done examining CE and its influence on employee behaviour, such as the new roles of engineers as technology intrapreneurs (Menzel et al. 2007), the influence of transformational leadership style on intrapreneurial behaviour (Moriano et al. 2014), organizational antecedents leading to intrapreneurial behaviour and as a further step to intrapreneurship (Rigtering and Weitzel 2013), the influence of intrapreneurial experience on CV (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2013) and bootlegging behaviour of employees to develop ideas not supported by management (Globocnik and Salomo 2015). Three articles also tried to link the organizational and individual levels by developing a combined model of CE and intrapreneurship to predict innovative behaviour (Åmo and Kolvereid 2005), clarifying the intersection of CE and intrapreneurship (Åmo 2010), or developing a link between EO and intrapreneurship (Bouchard and Basso 2011).

In addition to thematic diversity, the articles in the sample also applied different methodological approaches. As shown in Table 3, most authors used a quantitative research design (69%) to examine intrapreneurship. Only seven articles concerned qualitative research, applying interviews and case studies. Six articles drew on case studies, of which two applied a multiple case study approach. Furthermore, theoretical research work is underrepresented, as only three publications were of a conceptual nature. As is apparent from the sorting of the publications in Table 3 by year of publication, qualitative research designs were mainly employed from 2005 to 2010. From 2010 onward, quantitative research outweighed qualitative and conceptual research, a development that is quite typical of emerging research fields. Most of the quantitative publications were based on large and well-known databases, such as the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) survey or the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Data (PSED). Almost all studies were cross-sectional and only one applied a longitudinal research approach, using interviews to analyse the changed role of engineers and a shift from engineering to entrepreneurial tasks.

The sample contained no article giving an overview of prior research in the field of intrapreneurship or a review of the literature in this field. This further underlines the need for an SLR undertaken to map the literature streams and focus on intrapreneurship research at the individual level.

4 Results

4.1 Theoretical frameworks and perspectives on intrapreneurship

The sample articles used various theoretical perspectives to investigate individual-level intrapreneurship. The majority of the journal articles clearly defined a theoretical foundation; indeed most were based on more than one theory. Only two empirical publications lacked a clarification of the theoretical framework. In terms of definitions provided in the sample articles, the theoretical concepts of intrapreneurship, CE and EO were the theoretical foundations most mentioned. Pinchot’s work (1985), as seminal in the field, was applied in eight contributions focusing on the concept of intrapreneurship, defining intrapreneurs and distinguishing intrapreneurship from other concepts. Besides meeting the inclusion criterion of a focus on individual-level intrapreneurship, some papers also applied organizational-level constructs. Articles based on the CE approach tend to be rooted in the work of Antoncic and Hisrich (2003), as they clarified the intrapreneurship concept and developed a framework to distinguish CE from intrapreneurship, as well as dimensions of organizational-level intrapreneurship. A second source applied to CE research is the work of Kanter (1984). She underlined the relevance of initiatives undertaken by individuals within organizations and stated that CE should result in innovation behaviour among employees. Articles using the EO framework are based on the idea that EO is an organization-wide strategy for fostering innovation. Covin and Slevin (1991) identified innovativeness, risk taking and proactiveness as dimensions for measuring organizations’ EO and hence their work also provides a framework for the sample articles.

Besides the basic theoretical foundations rooted in the related concepts of intrapreneurship, CE and EO, the sample articles applied various lenses and theories to investigate intrapreneurship. Three theories, presented here, were applied most in the journal articles analysed. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) is well-established in the intention literature and relevant for analysing entrepreneurial intentions (Ajzen 1985, 1991). It is assumed that intentions predict human behaviour and therefore are of high relevance in research. Based on the assumption that attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control influence intentions, intrapreneurship research has attempted to delineate differences in entrepreneurial versus intrapreneurial intentions (Douglas and Fitzsimmons 2013; Tietz and Parker 2012). By investigating attitudes (e.g. to income and risk), researchers have aimed to shed light on intrapreneurial intentions and factors influencing these. Furthermore, motivation theories are applied in the sample articles to examine motivational factors for engaging in innovative behaviour within established organizations (Bicknell et al. 2010). In addition, different motives, e.g. financial and independence, have been investigated with regard to intrapreneurial intentions. The third theory most used is social learning theory (Bandura 1986), which states that the learning of novel behaviour is a cognitive process embedded in a social context and occurs through observation and imitation of others. The theory suggests that cognition, behaviour and environment are connected in a reciprocal fashion. The construct of “self-efficacy” is part of social learning theory (Bandura 1977) and is defined as a person’s perceived ability to show certain behaviours or fulfil certain tasks. Self-efficacy is influenced by skills, their application and the feedback on applying these skills. Therefore self-efficacy is not only the result of performance, but is also the determinant for further and revised performance. In the field of entrepreneurship, the term entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) has been established. The sample articles examined the ESE of employees and its key role in showing innovative behaviour and forming intrapreneurial intentions (Douglas and Fitzsimmons 2013; Globocnik and Salomo 2015; Wakkee et al. 2010).

In addition to the various theoretical lenses, the researchers also employed different definitions of intrapreneurship. As no common definition exists with regard to the perspective applied to the phenomenon, the journal articles examined specified intrapreneurship differently. Most researchers drew on Pinchot’s work (1985) and used well-known criteria to specify the term intrapreneurship. The majority of the research primarily characterized intrapreneurship through its organizational context (22 articles) by defining it as “entrepreneurship within existing organizations”, “entrepreneurship in the large organization”, “inside an organization”, “in-company entrepreneurship” or “entrepreneurial activities within the organizational context”. This is in line with Pinchot’s argument that the organizational context in particular differentiates entrepreneurship from intrapreneurship. A further criterion is the origin of intrapreneurial initiatives. In this regard, some studies (nine) clearly branded intrapreneurship as “bottom-up”, indicating that intrapreneurial activities emerge from entrepreneurial employees themselves. These publications argued that employees play a key role in realizing intrapreneurial initiatives. Other publications (seven) do not use the term “bottom-up” in their definition, but instead underline the relevance of individuals to intrapreneurship. Two publications concretely distinguish intrapreneurship as an “individual-level concept” from CE as an organizational-level concept. A further attribute often used to define intrapreneurship is the (expected) outcome (13 articles). Terms like “innovation”, “strategic renewal” and “out-of-the-box thinking” were applied to flag intrapreneurship as behaviour in pursuing new opportunities and competitive advantage. Besides the constituents of these main attributes mentioned above, the authors used different terms for intrapreneurship. Therefore, the result is a puzzle of similar terms and synonyms that lead to the mixing of different theoretical perspectives (e.g. using the term CE to examine individual employee behaviour).

4.2 Research streams

The articles in the SLR were organized into different research streams based on the analytical level applied. As Table 1 shows, by clustering, five streams dealing with different perspectives on intrapreneurship research were defined: individual- and organizational-level perspectives, context-oriented research, research focusing on outcomes and studies concentrating on possible promoting factors of intrapreneurship. To cluster the research, both deductive codes (e.g. individual level), based on the theoretical foundations of the studies, and inductive sub-codes (leadership) that emerged from the data were deployed.

In the following sections, an overview of the research done in the various identified streams is provided. As shown in Table 1, the streams identified follow a specific flow: the first is based on the individual- and organizational-level perspective from the intrapreneurship literature; the next stream focuses on context orientation in research; further research examines the possible outcomes of intrapreneurship and in addition factors further promoting intrapreneurial activities. The research stream focusing on individual-level factors is divided into two sub-categories of operational-level employees and middle-level managers, as they play different roles in the intrapreneurship process due to their relative positions in established organizations.

4.2.1 Individual-level perspective on intrapreneurship

Operational-level employees Various authors have examined factors predicting the innovative and entrepreneurial behaviour of the individual employee. An applied focus on demographic characteristics showed mixed results. Research work on education and age shows negative associations with innovation (Camelo-Ordaz et al. 2012). In contrast, other research shows that high levels of education increase the likelihood of intrapreneurship (Urbano and Turro 2013). Therefore, investigations focusing mainly on demographic variables are divergent and vague. In response, one approach often used in the entrepreneurship field to examine individual-level characteristics focuses on personality traits. Intrapreneurship researchers have tried to examine personality factors to identify intrapreneurs within organizations based on their specific traits (e.g. Williamson et al. 2013). Based on the Big Five model, researchers have described specific traits that point to innovative employee behaviour. Sinha and Srivastava (2013) examined the impact of personality traits and work values on innovative employee behaviour (the authors call it intrapreneurial orientation). Their research reveals that extraversion and the work values of altruism, creativity, management and achievement are positively associated with innovative behaviour. The results also show a negative association between neuroticism and intrapreneurial orientation. Research based on the entrepreneurial value system shows that values such as persistence, ambition, creativity, risk taking and optimism can be said to influence innovation performance (Camelo-Ordaz et al. 2012). When looking at these results, it should be borne in mind that the authors investigated individual-level factors in the context of creative firms and found that values such as creativity are of high importance by nature. As a further individual characteristic, initiative seems to play a key role, as employees with personal initiative are more likely to be intrapreneurs and are also more involved in intrapreneurial projects (Rigtering and Weitzel 2013). In line with this, Åmo (2010) identified employees as the initiators of and main contributors to innovation processes. The author argued that based on this, it is possible to determine if the innovation behaviour of employees is intrapreneurship (bottom-up) or rather CE (top-down) driven.

Zhu et al. (2014) also investigated personal characteristics and their research offers detailed insights. In the context of an intra-organizational idea contest, the authors examined the effect of the creativity and proactivity of employees on their performance in this contest. To this end, they measured the number of ideas contributed, the number of ideas accepted and the number of comments on others’ ideas. The results show that a higher level of creativity is positively related to higher numbers of ideas being contributed, whereas a higher level of proactivity is positively related to higher numbers of ideas being accepted. Based on their research, the authors developed a framework of four different innovation roles: follower (low creativity and proactivity), proactive founder (low creativity and high proactivity), creative innovator (high creativity and low proactivity) and intrapreneur (high creativity and proactivity). Hence, they underlined the characteristics of intrapreneurs as follows: “they are a combination of thinker, doer, planner, and worker. They combine vision and action” (Zhu et al. 2014, p. 1440015-12).

One limitation of research focusing on personality is the static character of traits. To take into account a more dynamic perspective, research concentrating on entrepreneurial behaviour is also a research approach identified in this field. Drawing on the TPB, Kirby (2006) highlighted individuals’ attitudes, perceived ability to be entrepreneurial and social support as relevant factors in fostering intrapreneurship. Research on different attitude types and entrepreneurial careers has shown that attitudes to income, independence and ownership are related to entrepreneurship, whereas intrapreneurship is related to a weak risk tolerance. Also, the motives for potential intrapreneurs to show a certain behaviour have been analysed. Research on financial, independence, recognition and role model motives undertaken by Tietz and Parker (2012) shows that the same motives that stimulate nascent venturing have the reverse effect on being selected by an organization into intrapreneurship. Closely linked to behaviour—and therefore the TPB—is the topic of perceptions. In intrapreneurship research, perceptions concerning risk and uncertainty in particular are of high relevance in distinguishing intrapreneurs from entrepreneurs. The results of research show that intrapreneurs are quite similar to entrepreneurs with regard to uncertainty and risk perceptions (Matthews et al. 2009). In contrast, intrapreneurs seem to be more elaborate planners, with higher growth expectations. The authors explained these results based on the established organizational environment of intrapreneurs, which forces them to engage in planning activities that in turn also lead to higher growth expectations. In addition, the research of Martiarena (2013) shows that intrapreneurs present greater levels of risk aversion and lower levels of expected earnings than entrepreneurs.

One main research stream focuses on the human capital of intrapreneurs. Following prior research, the sub-categories distinguish between general and specific human capital related to intrapreneurship. General human capital refers to skills, knowledge and experiences that are useful in multiple situations, whereas specific human capital refers to content-specific situations that are primarily useful in intrapreneurial situations. One main contribution referring to general human capital is the work of Parker (2011), who examined the issue of entrepreneurship or intrapreneurship. He identified several factors and pointed out that general human capital leads to start-up activities (entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship)—and to entrepreneurship in particular—as it is useful in various situations within and outside an existing organization. Other research applying human capital theory also points to the relevance of general human capital in terms of the provision of necessary entrepreneurial skills (Gwynne and Wolff 2005; Martiarena 2013) and competencies. Bjornali and Støren (2012) concentrated on different competencies and investigated their influence on innovative employee behaviour. They examined the effect of different types of competencies, as well as participation in entrepreneurship education programmes among European higher education graduate professionals. The authors’ research shows interesting results, as professional/creative competencies and communicative/championing competencies increase the employees’ probability of introducing innovations at work, whereas competencies related to efficiency and productivity do not. Bjornali and Støren (2012) highlighted the relevance of a third competence type, i.e. brokering. Employees with brokering competencies are able to combine knowledge with organizational knowledge, social capital and networking skills. Therefore, with regard to intrapreneurial behaviour, brokering competencies are of special interest. Entrepreneurship education programmes were also found to increase the likelihood of introducing innovations at work.

In contrast to the factors mentioned above, specific human capital focuses on specific—in this case intrapreneurship-oriented—skills and experiences. Similar to the case of entrepreneurship, opportunity recognition plays a significant role when it comes to intrapreneurship. Research results show that the ability to identify business opportunities enhances the opportunity for intrapreneurship (Urbano and Turro 2013). Detailed research stresses opportunity recognition as an important factor in defining intrapreneurs in contrast to entrepreneurs and employees: entrepreneurs recognize more business opportunities than intrapreneurs, but intrapreneurs recognize more business opportunities than employees (Martiarena 2013). Opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial opportunities have also gained in importance for engineers. Research based on a longitudinal study of graduate engineers revealed that engineers’ tasks underwent a shift from recognizing engineering to entrepreneurial opportunities (Solymossy and Gross 2015). In addition, the authors investigated different types of knowledge and their value. The results estimate that potential knowledge (the adaptability to transfer knowledge) is of particular value to firms as it enables them to adapt to changes. Potential knowledge lies in the individual and can been seen as intellectual property. If firms do not value this, individuals will want to maximize their personal return on the potential knowledge and therefore will decide either to become entrepreneurs or to foster intrapreneurial activities. As a further factor, business planning activities are a distinctive feature of entrepreneurs versus intrapreneurs. Due to the established organizational environment, intrapreneurs are tied to planning activities and hence also show higher levels of business planning activities (Matthews et al. 2009). One relevant entrepreneurship-specific aspect with regard to intrapreneurship again concerns the concept of ESE. Individuals’ perceptions of their ability to meet competitive challenges will influences entrepreneurial employee behaviour. Johnson and Wu (2012) examined the influence of external entrepreneurial support and stated that ESE is a “pull” factor for entrepreneurship. In particular: “their perception of certainty may provide the extra confidence for an already overly optimistic individual, thereby boosting their entrepreneurial self-efficacy leading to the eventual exodus from the corporation” (Johnson and Wu 2012, p. 342). The crucial role of ESE is also part of the work of Douglas and Fitzsimmons (2013), who examined differences in entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions. ESE was related to both entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial intentions, but showed a higher level of significance for entrepreneurial intentions. Douglas and Fitzsimmons speculated that individuals with higher ESE are more likely to engage in self-employed behaviour and individuals with lower ESE also intend to be entrepreneurial, but as intrapreneurs within an organization. In line with this, Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue (2013) examined specific human capital and its influence on corporate venturing activities. They investigated the effect of intrapreneurial experiences and found that employees with intrapreneurial experience are more likely to create a corporate venture for the organization. Their results also indicate that the effect of intrapreneurial experiences on corporate venturing is higher than that of other human capital forms based on education level. Similarly, Globocnik and Salomo (2015) stressed the relevant role of intrapreneurial self-efficacy. They argued that employees with high levels of intrapreneurial self-efficacy are convinced of their abilities and may even exhibit bootlegging behaviour to develop their ideas further.

As entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs are embedded in social systems, it is not surprising that another focus in intrapreneurship research is on social capital. Intrapreneurs’ networks and their roles are issues in intrapreneurship research. The individual’s personal network (Urbano and Turro 2013), networking skills (Gwynne and Wolff 2005) and relationships outside the organizations’ boundaries (Bicknell et al. 2010) seem to be relevant individual characteristics of intrapreneurs. These results are especially in line with Pinchot’s (1985) original idea of intrapreneurs and their ability to think across organizational boundaries. In line with social capital (Coleman 1988) and social network theory, the results indicate that social capital is a specific form of resource that originates from interaction and facilitates individuals’ actions. A main requirement for benefiting from social ties and the capital residing in them is trust. As demonstrating intrapreneurial behaviour within an organization often means departing from the usual way of doing things and challenging confirmed habits, it is not surprising that trust also plays a key role in the intrapreneurial context (e.g. Edú Valsania et al. 2016). Wakkee et al. (2010) highlighted the relevance of trusting relationships between employees and managers in influencing employees’ ESE perceptions and increasing their self-efficacy. These results are also in line with the work of Rigtering and Weitzel (2013), who indicated the importance of trust in managers as an influence on intrapreneurial behaviour.

A further research focus derives from the fact that intrapreneurs are embedded in established organizations and hence focuses on the individuals’ organizational affiliation. Prior research has suggested that entrepreneurial employees leave the corporation and implement their own ideas due to dissatisfaction. However, in contrast to this assumption, Johnson and Wu (2012) revealed a different logic. Considering entrepreneurship versus intrapreneurship, they tested the job satisfaction model and the person-environment fit model. Their research does not support the assumption that employees quit the organization due to dissatisfaction; rather, their results show that nascent entrepreneurs leave the corporation with high levels of job satisfaction. The authors argue that this is the case because nascent entrepreneurs, whilst working as employees, collect experience of the industry and afterwards leave the corporation to start a new business within the same industry. Therefore, nascent entrepreneurs are satisfied with their job but still leave the corporation to start their own venture. Further research work taking into account affiliation to an organization shows that the individual’s organizational tenure negatively affects intrapreneurship in terms of innovation performance. Camelo-Ordaz et al. (2012) argue that long organizational tenure is associated with a passive attitude to decision making, resistance to change and therefore a reduced willingness to exhibit innovative behaviour und implement new ideas. Another factor is the employees’ organizational identification. Moriano et al. (2014) examined its effect on intrapreneurship and found organizational identification to be positively related to intrapreneurial behaviour. Employees identifying with their organization experience the organization’s success and failure as personal success and failure, are strongly engaged and therefore show some “extra-role” behaviour. These employees are highly motivated to show behaviour over and above their organizational role und hence to engage in intrapreneurial behaviour.

Middle-level managers Besides the focus on the individual operational level employees, a second stream emerges from research concentrating on management issues and managers with regard to intrapreneurial behaviour within organizations. In this regard, middle-level managers’ personalities and behaviour and their influence on employees are of particular interest. Research shows that managers’ personalities and attitudes are key factors driving intrapreneurial activities within an organization (Bouchard and Basso 2011). As a further step, research has also examined managers’ behaviour. Kuratko et al. (2005) noted the special role of middle-level managers as they are a relevant tie between top-level management’s CE perceptions and lower-level management’s intrapreneurial initiatives. In their research, the authors focused on middle-level managers’ entrepreneurial behaviour by examining their role with regard to intrapreneurship. Middle-level managers endorse, refine and shepherd entrepreneurial opportunities and as a further step identify, acquire and deploy necessary resources to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities. The authors emphasize that “middle-level managers endorse CE perspectives coming from top-level executives and ‘sell’ their value creating potential to the primary implementers—first-level managers” (Kuratko et al. 2005, p. 705). They stress that there is an individual-level outcome of entrepreneurial behaviour. A personal positive evaluation affects the middle-level managers’ perceptions and thus leads to engagement in entrepreneurial behaviour.

Not only has middle-level managers’ individual entrepreneurial behaviour been investigated, but also middle-level managers’ influence on other employees. Moriano et al. (2014) examined management practices and their effect on intrapreneurship. They examined the influence of leadership styles in combination with employees’ organizational identification on intrapreneurial behaviour. Their research indicates that transformational leadership (associated with adopting the organization’s vision and achievement of collective goals) is positively related to intrapreneurial behaviour. Furthermore, organizational identification mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and employees’ intrapreneurial behaviour. This underpins the relevance of managers’ behaviour and their potential to foster intrapreneurial behaviour. Also, authentic leadership, labelled as future-oriented, proactive and trustworthy leaders, is positively related to employees’ intrapreneurial behaviour. Edú Valsania et al. (2016) investigated the relationship between authentic leadership and employees’ intrapreneurial behaviour and possible mediators. Similar to Moriano et al. (2014), their results show that organizational identification partially mediates this relationship. Based on these research results, the authors note the relevance of an appropriate leadership style as an antecedent of intrapreneurship.

4.2.2 An organisational-level lens on intrapreneurship

Based on the assumption that individual-level initiatives, as well as organizational-level approaches such as CE, are necessary to enable intrapreneurial behaviour (Åmo and Kolvereid 2005), a second stream of research offers an organizational-level lens on intrapreneurship. By focusing on organizational structures and processes that permit intrapreneurship, research offers insights into influential organizational characteristics such as the role of the business owner, planning activities or formalization (Bouchard and Basso 2011). Various formal management processes that allow strategic autonomy, for example, are relevant factors in ensuring an intrapreneurship-friendly environment (Feyzbakhsh et al. 2008; Globocnik and Salomo 2015). Furthermore, organizational-related promoters offer an appropriate physical environment that creates physical nearness and stimulates various aspects of cooperation, as well as a reduced hierarchy and bureaucracy to ensure knowledge sharing and joint idea generation (Menzel et al. 2007). Authors have also stressed organizational empowerment as one important factor. The concept of empowerment allows employees to develop proactive behaviour through the implementation of an organizational structure that aims for the autonomy and commitment of employees in decision-making processes. The experience of organizational empowerment is a success factor and even mediates the relationship between authentic leadership and intrapreneurial behaviour (Edú Valsania et al. 2016). Menzel et al. (2007) further highlight the need for new methods in the teaching and training of intrapreneurship. Simulations and action-orientated approaches are useful preparing employees for intrapreneurship. Therefore, management processes should also shed light on suitable training tools to pioneer the intrapreneurial behaviour of employees.

As a second sub-category, organizational support and promoters are said to play a crucial role in fostering intrapreneurship activities (Urbano and Turro 2013). In particular, the role of management in fostering intrapreneurship in practice is of considerable relevance, as management acts as enabler for demonstrating entrepreneurial behaviour within the organization. Parker (2011) argues that potential intrapreneurs do not express interest in entrepreneurship until management, for example, presents a suitable opportunity. Various studies have demonstrated that the realization of intrapreneurial activities requires management support (Feyzbakhsh et al. 2008; Kirby 2006). In particular, management’s clear commitment to intrapreneurship is a precursor for intrapreneurial activities and as a further step an intrapreneurship-friendly environment within the established organization. In addition to management support, high availability of resources leads to higher levels of intrapreneurial behaviour (Menzel et al. 2007; Rigtering and Weitzel 2013). Therefore, access to resources is an important organization-related promoter of intrapreneurship. Not only do support by managers and the availability of resources affect potential intrapreneurs, but also the opportunity to participate in various decision-making processes influences intrapreneurship initiatives on the part of employees. Research states that low organizational participation (with employees being the main contributors to processes) and high horizontal participation (broadly defined jobs of employees) are positively related to intrapreneurship (Åmo 2010; Rigtering and Weitzel 2013). Closely linked is also the communication of organizational strategies to employees as a success factor, strengthening the commitment and participation of employees. To complement organizational support, rewarding intrapreneurs has also been examined in research. Besides honouring the innovative accomplishments of intrapreneurs (Globocnik and Salomo 2015), rewards provide a signalling effect within the organization und emphasize intrapreneurial behaviour as desirable (Kirby 2006; Menzel et al. 2007).

As well as the parameters presented above, an underlying success factor of intrapreneurship is an organization-wide intrapreneurship culture. Authors have shown that the development of an intrapreneurial mindset allows organizations to foster an intrapreneurship culture and further facilitates organizational change (Hagedorn and Jamieson 2014). As intrapreneurs are characterized by their broad mindset, enabling them to cooperate and generate ideas across organizational boundaries, the culture needed is defined by trial and error, an innovative mindset and opportunities for experimenting and continuous refinement (Hagedorn and Jamieson 2014; Kirby 2006; Menzel et al. 2007).

4.2.3 Context orientation in intrapreneurship research

Besides the perspectives concerning the influence of individual- and organizational-related factors on intrapreneurship, research in the field also focuses on context orientation. Researchers have examined not only different firm types, but also the national level, as well as the technological and academic context.

The first stream consists of research work concentrating on different firm types. Bouchard and Basso (2011) examined factors at the organizational level of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). The authors aimed to link the organizational concept of EO with the individual-level concept of intrapreneurship. By examining the effect of managers’ personalities and organizational characteristics on EO and managers’ attitudes on intrapreneurship, Bouchard and Basso identified two different types of SMEs: traditional SMEs (with a central role of the owner, limited planning activities and informal structure) and in contrast to this, “miniature large firms” (with less centrality of the owner, more planning and some formalization of structure). From this perspective, EO and intrapreneurship are not simple correlated constructs, as it is possible that firms will show various combinations of EO (high or low) and intrapreneurship (high or low). Hence the authors propose that in traditional SMEs high EO will be associated with low or no intrapreneurship, whereas in miniature large firms high EO will be associated with diffuse intrapreneurship activities. Camelo-Ordaz et al. (2012) took a closer look at micro firms in the creative business sector. The authors investigated individual characteristics and intrapreneurs’ entrepreneurial value systems (e.g. creativity) with regard to innovation. Due to the creative context, the authors pointed especially to the role of business background. Business background, namely possessing the necessary managerial skills, was found to have a negative influence on innovation performance in micro firms, whereas creative background was found to exert a positive influence on innovation performance. Looking at these results, the special context of creative firms should be borne in mind. Furthermore, the field of business seems to be an interesting factor regarding intrapreneurship. Parker’s (2011) research shows that business-to-customer opportunities are associated with entrepreneurship and business-to-business opportunities rather lead to intrapreneurship, possibly due to industry-specific knowledge, greater access to resources and the higher legitimacy of established organizations.

Besides the perspective on various firm types, one paper also considered the national-level perspective. As well as individual-level factors, Urbano and Turro (2013) examined external factors (at the national level), such as fear of failure, successful storytelling and procedures for creating a company. The authors argue that a high level of education, the individual’s personal network and the ability to identify business opportunities increase the opportunity for intrapreneurship. However, surprisingly research displays no significant effect of external factors, which are probably diminished by the need to achieve economic results.

In addition to the diverse perspectives mentioned above, two other streams in intrapreneurship research have emerged as an answer to changed conditions in practice. One such stream concentrates on intrapreneurship in the technological context. As intrapreneurship is closely linked to innovation, this is not surprising. One theme is the new role of engineers within organizations. Due to changes in the work environment, engineers are facing managerial responsibilities within firms and contribute to innovations throughout the whole innovation process. Therefore, the role of engineers has changed. Menzel et al. (2007) concentrate on technology intrapreneurs and describe how engineers become active in intrapreneurship. They identify organizational-related promoters of engineers’ intrapreneurship. The physical environment, reduction in hierarchy and bureaucracy, rewarding behaviour, coaching for intrapreneurs and available resources are shown to be relevant factors. In addition, Williamson et al. (2013) focus on the new role of engineers. In contrast to Menzel et al. (2007), who focused on organizational-related factors, they examine various personality traits (For detailed results on all tested traits see Williamson et al. 2013, p. 161.). The results reveal that engineers differ from non-engineers and the authors indicate the relevance of this result with regard to finding engineers fitting into the new role within firms. Research based on a longitudinal study of graduate engineers also reveals that engineers’ tasks have undergone a shift from recognizing engineering to recognizing entrepreneurial opportunities (Solymossy and Gross 2015). Based on the new role of engineers, the development of skills has also become the focus of research. Gwynne and Wolff (2005) provided some insights into a special programme for (women) scientists entailing networking, workshops, advice and mentoring to develop intrapreneurial skills.

A further research stream focuses on intrapreneurship in the context of academia. Kirby (2006) called for the creation of entrepreneurial universities to allow students and staff to commercialize their intellectual property and ideas. He argued that universities have spent decades on learning how to routinize and control processes and therefore are facing barriers in developing an entrepreneurial mindset. Hence, by drawing on individuals’ attitudes, perceived ability to be entrepreneurial and social support (TPB), as well as intrapreneurship theory, he highlighted relevant factors for developing entrepreneurial universities. With regard to intrapreneurship, he especially noted the need for management support of entrepreneurship, a university-wide model of entrepreneurship, an intrapreneurial culture and the rewarding of intrapreneurs. Bicknell et al. (2010) also address the topic of intrapreneurship in academia and focus on academic staff engaging in knowledge transfer activities. The underlying motivation of these academics is to use their academic knowledge for a wider purpose than research and teaching. The authors term the knowledge transfer among active academics as academic intrapreneurship. In their research, they identify “pull factors” for engaging in knowledge transfer. For instance, academic intrapreneurs are proactive in networks and relationships outside academia and value the moderate risk of being entrepreneurial within the university. In particular, proactiveness and risk aversion point to academics having an intrapreneurial role.

Hagedorn and Jamieson (2014) also focused on intrapreneurship in the academic context and highlighted the need for an entrepreneurial mindset, but instead of concentrating on staff in particular, they focused on how organizational change in academia can be implemented. The authors argued that academia is facing several challenges (e.g. tightening budgets and intensive competition) and therefore an intrapreneurial mindset is necessary to redefine academia’s strategic capabilities. Furthermore, this requires the collective development of mental modes that encourage an intrapreneurial and innovative mindset in academia.

4.2.4 Outcome lens on intrapreneurship

The fourth research stream that emerged applied an outcome perspective on intrapreneurship. Various studies have focused on possible outcomes of intrapreneurial behaviour. As intrapreneurship is a sub-field of entrepreneurship, one sub-category concentrates on the difference between entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship. By focusing on possible behavioural outcomes of intrapreneurship, authors have examined the issues of the differences between entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship. As already explained in 4.2.1, based on research multiple distinguishing features have been investigated: expectations, uncertainty, risk preference, human capital, job satisfaction, field of business and intentions (Douglas and Fitzsimmons 2013; Johnson and Wu 2012; Matthews et al. 2009; Parker 2011). Even motives have been considered to differentiate possible nascent venturing from possible nascent intrapreneurship (Tietz and Parker 2012). However, Parker (2011) also stated that there are unobservable attributes that result in entrepreneurship rather than in intrapreneurship. With regard to CV, research points to intrapreneurial experience as a specific form of human capital that leads to a higher willingness to engage in CV activities (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue 2013). Only one study in the sample investigated the outcome perspective at the national level. Based on the idea that knowledge created in an organization is an important source of entrepreneurial opportunities, Stam (2013) examined innovation indicators in correlation with total entrepreneurial activity (TEA) and entrepreneurial employee activity (EEA) at a national level. The results show that innovation indicators such as gross expenditure on R&D are positively related to EEA but are not related or are even negatively related to TEA. Stam (2013) argued that knowledge and innovation are primarily linked to intrapreneurship. Radical innovations are likely to be recognized by employees within knowledge-intensive organizations. Therefore Stam (2013) clearly linked innovation to intrapreneurship and stated that entrepreneurship is only marginally innovative.

A further sub-category deals with intrapreneurial activities in detail. Åmo and Kolvereid (2005) examined factors predicting innovative behaviour. They tested different models and the proportion of variance in innovation behaviour: one model based on the CE literature (an organization’s strategic orientation towards entrepreneurship), one model based on the intrapreneurship literature (intrapreneurial personality) and a combined model. The results showed that the combined model of CE and intrapreneurship explained a significantly higher proportion of variance in innovation behaviour. This underlines Åmo and Kolvereid’s (2005) point that innovative behaviour is a result of both CE and intrapreneurship. In further research, Åmo (2010) again pointed to the need for clarification of the similar but diverging terms of CE and intrapreneurship. In his research, he clearly defined employees’ innovation behaviour as a connection between the two theoretical perspectives, bottom up and top down.

Similar to the work of Åmo and Kolvereid (2005), Rigtering and Weitzel (2013) developed a two-step model of intrapreneurship based on prior work. Their work shows that employees need to address two steps to be intrapreneurs. First, intrapreneurship is stimulated by the organization, as employees are able to develop and identify opportunities (intrapreneurial behaviour). As a second step, the employees are actively involved in innovation projects (intrapreneurship). Examining formal and informal work contexts, the authors state that horizontal aspects of participation at work, available resources and trust in managers lead to higher levels of intrapreneurial behaviour (concerning innovative behaviour and personal initiative, but not risk taking). In a second step, their research shows that employees exhibiting innovative behaviour and personal initiative are more likely to be intrapreneurs and are also involved in more intrapreneurial projects. Risk taking does not have a significant effect. Thus, the authors show that intrapreneurship is only indirectly affected by work context, namely through individual-level factors, such as innovative workplace behaviour and personal initiative. To further stimulate intrapreneurship, management and leadership styles play an important role and help foster the existing intrapreneurial potential of employees (Moriano et al. 2014). The intrapreneurial behaviour approach combines the individual- and organizational-level perspectives, as well as the intrapreneurship and CE levels, and is therefore in line with Åmo’s (2010) notion that the perspective on employees’ innovative behaviour takes into account management’s role as an enabler and employees’ individual decisions to engage in innovative behaviour.

Research on employees’ innovation behaviour provides diverse approaches in further describing intrapreneurs. Based on an ownership dimension, the research of Martiarena (2013) divided intrapreneurs into four different categories to differentiate between entrepreneurs, engaged intrapreneurs (new business activity for corporations, expecting to demand an ownership stake), intrapreneurs and employees (both within a corporation). The results show that the self-perception of entrepreneurial skills is positively related to entrepreneurship and engaged intrapreneurship, as intrapreneurs who believe in their own entrepreneurial ability demand an ownership stake of a new corporate business and become engaged intrapreneurs. Nonetheless, Martiarena (2013) indicates that engaged intrapreneurs are similar to entrepreneurs, whereas intrapreneurs are similar to employees. Bager et al. (2010) further divided intrapreneurs into four sub-categories: project intrapreneurs, venture intrapreneurs, spin-off entrepreneurs and independent entrepreneurs. Their results reveal that intrapreneurs are similar to entrepreneurs, but appear to be more experienced and growth oriented. Likewise, spin-off entrepreneurs seem to be more experienced and growth oriented than independent entrepreneurs. Moreover, they quickly attain higher performance than their independent counterparts. In addition, the authors estimate that these four sub-categories need further examination and that management support appears to play a key role.

One sample article also examined a specific form of employee behaviour of intrapreneurs: bootlegging. In this case, employees develop their ideas without formal legitimization by ignoring formal structures. Globocnik and Salomo (2015) examined whether formal management processes and intrapreneurial self-efficacy lead to bootlegging behaviour. The authors show that strategic autonomy, rewards for innovation accomplishments and also intrapreneurial self-efficacy are indicators for bootlegging behaviour (bootlegged projects, bypassing official channels and providing own resources to develop ideas). Surprisingly, the results show a negative effect of front-end formality (formal mechanisms for idea exploration, development and selection) on bootlegging. This implies that to some extent formal structures are needed to guide employees’ innovation behaviour.

Only a few papers have applied an outcome perspective, investigating the relationship between intrapreneurship and measureable performance: intrapreneurial behaviour and its influence on performance in an idea contest (Zhu et al. 2014), business performance of spin-off entrepreneurs (Bager et al. 2010) and innovation performance in creative firms (Camelo-Ordaz et al. 2012). Hence the sample articles have mainly focused on performance in terms of innovative or creative outcomes, rather than objective business performance measures, such as key financial data.

4.2.5 Factors promoting intrapreneurship

The papers in the last research stream deal with additional factors promoting intrapreneurship. Kuratko et al. (2005) highlight the key role of middle-level managers in their research. Due to their role and tasks in motivating employees, acquiring necessary resources and selling innovative ideas to top-level management, middle-level managers can themselves be defined as intrapreneurs. The authors therefore also argue that middle-level managers behave in an entrepreneurial manner and that there is an individual-level outcome of this behaviour. As a further step, positive evaluation of this behaviour affects individual perceptions and leads to increased engagement in intrapreneurship in the future. Therefore, the role of managers is crucial in motivating operational-level employees, but at the same time the entrepreneurial behaviour undertaken also promotes the intrapreneurial initiatives of employees and managers.

Belousova and Gailly (2013) also point to the promotional role of middle-level managers and present interesting results concerning the contribution of different organizational members in line with the CE process. The so-called dispersed CE process is divided into the stages of discovery, evaluation, legitimation and exploitation. The authors show that different levels of organizational managerial membership (top-, middle- and operating-level) are involved in this process. The role of middle-level managers is crucial as they encourage operational-level employees to work on innovative ideas and at the same time champion ideas in relation to management. In addition, the various stages of the process (e.g. evaluation, legitimation) are promoters, facilitating feedback, evaluation, continuous adjustment and experimentation.

In line with this, Wakkee et al. (2010) argue that with regard to intrapreneurial behaviour, there is a reciprocal connection between cognition, environment and behaviour. Thus intrapreneurial behaviour is not just the result of ESE. As showing behaviour allows feedback, intrapreneurial behaviour is also a determinant of ESE. The authors state that ESE has a positive effect on entrepreneurial employee behaviour, as a person’s perception of being capable of behaving entrepreneurially is reflected in actual entrepreneurial behaviour. A further promoting factor that has emerged from research is developmental support in the form of coaching (Menzel et al. 2007; Wakkee et al. 2010). As employee coaching by managers provides access to resources and strengthens the awareness of intrapreneurship, the role of coaching in entrepreneurial employee behaviour and ESE has been investigated. The results reveal a positive effect of coaching on intrapreneurial behaviour, demonstrating that coaching can be an important factor promoting intrapreneurship. In addition, workshops, developmental advice and mentoring (Gwynne and Wolff 2005) provide developmental support in fostering intrapreneurial skills and promoting intrapreneurship.

5 Discussion and paths for future research

The purpose of this paper was to examine intrapreneurship research and identify the current research focus in the field. By mapping the current research, the paper has clearly distinguished intrapreneurship as distinct from the organizational concepts of corporate entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial orientation. The results of the systematic literature review indicate different analytical clusters of research focusing on intrapreneurship: studies related to individual- and organizational-level factors, contextual-oriented research, an outcome lens on intrapreneurship and research concentrating on possible promotional factors.

The articles explored in this review offer an overview of interesting and current key aspects in intrapreneurship research. Based on the results, it can be argued that corporate entrepreneurship as a top-down approach and intrapreneurship as a bottom-up approach (Åmo and Kolvereid 2005; Rigtering and Weitzel 2013; Sinha and Srivastava 2013) are definitely linked to each other. As stated, “there will not be any innovation without the individual being involved” and it “also involves the organisation as a given process parameter” (Menzel et al. 2007, p. 734). This is also in line with earlier conceptual work (e.g. Bouchard and Basso 2011), which pointed to the need for a combined perspective on the intrapreneurship phenomenon and the necessary integration of individual and organizational concepts. As researchers (e.g. Kuratko et al. 2005) have indicated, middle-level managers support CE activities from top-level managers and also promote their value to operational-level management; middle-level managers’ role is to link the constructs of CE and intrapreneurship within firms. Furthermore, due to their specific role in selling ideas and acquiring resources, middle managers themselves are intrapreneurs.