Abstract

Background

Attention Deficit-Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder, often persisting into adulthood.

Aims

To investigate the levels of functionality and quality of life (QoL) in adult patients newly diagnosed with ADHD and to compare with those without an ADHD diagnosis.

Methods

Consecutive patients who were referred to and assessed in a tertiary adult ADHD clinic enrolled in the study. Diagnosis of ADHD was based on DSM-5 criteria. Functionality was measured using the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale (WFIRS) and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF). QoL was assessed with the Adult ADHD Quality of Life Questionnaire (AAQoL).

Results

Three-hundred and forty participants were recruited, 177 (52.1%) females. Of them 293 (86.2%) were newly diagnosed with ADHD. Those with ADHD had significant lower functionality as it was measured with the WFIRS and GAF, and worse QoL (AAQoL) compared to those without. In addition, a significant correlation between GAF and WFIRS was found.

Conclusions

The results show that adults with ADHD have decreased functionality and worse QoL when compared against those presenting with a similar symptomatology, but no ADHD diagnosis. ADHD is not just a behavioural disorder in childhood, but a lifelong condition with accumulating problems that can lead to lower QoL and impaired functioning throughout adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by either significant symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity and impulsiveness or a combination of the two. The current diagnostic criteria for ADHD include six or more symptoms of inattention and six or more symptoms of hyperactivity–impulsivity, but for older adolescents and adults (from 17 years and above), five symptoms are required [1]. The pooled prevalence of ADHD in the general adult population is estimated at around 2.5% [2], but in selective populations like psychiatric outpatient clinics, the pooled prevalence is increased to 14.61% [3]. Although it has been seen as a childhood disorder which is believed to remit in adolescence, evidence is evolving of persistence into adult life [4]. Symptoms and associated functional impairments have been shown to fluctuate throughout adulthood in approximately 90% of cases [5]. Previous studies have shown that adults with ADHD have more functional impairment compared to healthy controls in several areas of functioning [6, 7]. This is not surprising as the DSM-5 criteria for ADHD, in addition to the presence of the core symptoms, requires (criterion D) that those symptoms interfere or reduce social, academic, or occupational functioning [1]. Therefore, level of functioning is an important aspect of the diagnosis of ADHD. Studies which have investigated and compared functionality of adults with ADHD to those with a mixture of other mental disorders showed that adults with ADHD had significantly worse functioning [7]. Moreover, it has been hypothesised that, in people with ADHD, this functional impairment may be more important in the causal pathway of stress, anxiety and mood than the specific symptoms of ADHD per-se [8].

Quality of Life (QoL) is a related construct to functional impairment which has long been explored in children with ADHD and is recently gained increasing attention in adults with ADHD. QoL refers to individuals’ subjective perceptions of their lives and is influenced by their culture and values [9]. The QoL typically focuses on and evaluates physical, psychological, social, and environmental factors. The presence of a disorder generally reduces the QoL, especially in cases of comorbidities or more severe disorder trajectories [10]. Previous longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have shown that the QoL of adults diagnosed with ADHD is lower compared to normal controls [10,11,12]. Treatment of ADHD improves both QoL and ADHD symptomatology [13,14,15].

Therefore, functional impairment and QoL are becoming increasingly recognized as important clinical components when considering how best to understand, support and treat adult ADHD. In this paper, we investigate functionality and QoL in a cohort of adults who have been referred to an ADHD clinic in Ireland for evaluation and treatment. The aims of the present study are: (a) to investigate and present the levels of functional impairment and QoL in adults newly diagnosed with ADHD, (b) to compare the levels of functionality and QoL between those diagnosed with ADHD and those who presented with similar symptomatology but do not fulfil the criteria for ADHD and (c) to investigate if there are differences in functionality and QoL among the different ADHD subtypes (combined, inattentive, hyperactive/impulsive). A secondary aim is to examine the concurrent validity (corelation) of the two function scales that we used in the present study: the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale (WFIRS) and the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF).

Methods

Design

Cross-sectional, observational study.

Setting

Consecutive outpatients attending an Adult ADHD clinic. The adult ADHD clinic is a tertiary level service. Referrals are accepted from the Adult Mental Health Services (AMHS) in line with the Republic of Ireland Health Service Executive (HSE) model of care [16]. These guidelines direct that patients are screened in AMHS using the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) [17], and Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) [18] scales. Those screening positive on both scales were referred to the ADHD Adult Clinic for further clinical diagnostic assessment and treatment.

Inclusion–exclusion criteria

All referred and consented patients were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were (a) patients with severe learning disability, or severe brain injury, and (b) patients not able to speak or read in the English language.

Measurements/Scales

Demographics

Demographic data provided by the respondent, included age, gender, marital status, employment status, and higher educational achievement.

The diagnostic interview for adult ADHD (DIVA 5)

The DIVA 5 is a semi-structured instrument with good correlation with other self-reported rating scales and is well-validated. It is based on the DSM-V diagnostic criteria for ADHD and is designed to aid clinical diagnosis of ADHD in adults [19]. It takes about 60 to 90 min to be completed.

Psychiatric clinical evaluation

All participants also had a psychiatric clinical evaluation according to DSM-5 criteria. The psychiatrist used all available information (not blind to the administered scales, including DIVA 5), collateral history from parents or other family members (where possible) and detailed semi-structured neurodevelopmental history.

Weiss functional impairment rating scale (WFIRS)

WFIRS is a self-reported scale and consists of 69 items which covers seven domains of functioning (family, work, school, life skills, self-concept, social, and risks). There is four-point Likert rating scale for each item ranging from zero (never or not at all) to three (very often, very much). Mean scores can be calculated by omitting items with a missing or ‘not applicable’ response [20]. The total mean scores of WFIRS ranging from 0 to 3 and a higher total mean score (or on each domain/subscale) indicates greater functional impairment. The psychometrics for this scale are characterised as good and it has been widely used in research and clinical practice [21, 22].

Adult ADHD quality of life questionnaire (AAQoL)

AAQoL was developed and validated to measure quality of life in patients with ADHD [23]. The psychometrics of the scale have been investigated in different studies and it is considered as a valid and reliable instrument [23,24,25]. It consists of 29 items with each item rated by patients on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. It yields a total score (based on all items) and four subscale scores: life productivity, psychological health, life outlook, and relationships. After reversing scores and transforming them to a scale from 0 to 100, higher scores indicate better quality of life.

Global assessment of functioning (GAF)

The GAF was initially developed by Luborsky [26] as a Health Sickness Rating Scale and was subsequently modified and included as axis V in DSM-III–R and DSM-IV. It has been dropped from the DSM-5 but remains widely used due to its simplicity and good psychometrics [27]. GAF scores ≤ 70 indicate clinically significant functional impairment [26]. It is rated by the clinician for evaluating a person’s psychological, social, and occupational functioning on a hypothetical continuum of mental health problems ranging from 1, representing the hypothetically sickest individual, to 100, representing the hypothetically healthiest. The scale is divided into 10 equal parts and provides defining characteristics (both symptoms and social functioning) for each 10-point interval. It has been validated in different settings, and its reliability is estimated to be 0.78 [27,28,29].

Ethics

The Local Research Ethics Committee approved the study. The procedures and rationale for the study were explained to all participants and written informed consent obtained.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was conducted using the IBM (SPSS) v25. For the first aim of the study, descriptive statistics were reported. Continuous variables are reported as means plus standard deviation, while categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages. If continuous variables were non-normally distributed, the median, minimum, maximum and Interquartile Rage (IQR) were reported. Comparison between the two groups (ADHD vs no-ADHD, second aim of the study) was conducted with a parametric (t-tests) for the normally distributed variables WFIRS and AAQoL and with a non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney test) for the non-normally distributed GAF. To compare the outcome variables functional impairment and quality of life among the three ADHD subtypes (third aim of the study), one way ANOVA for the normally distributed variables WFIRS and AAQoL, and the Kruskal–Wallis test for the non-normally distributed GAF were used. For the fourth aim of the study (concurrent validity of WFIRS and GAF), given that GAF was non-normally distributed, a Spearman’s rho test was performed. Finally, for the post hoc power calculations, the G*Power 3.1 program was used [30].

Results

Descriptive statistics

Demographics

The mean age of participants (n = 340) was 30.78 (SD: 10.475), median 29, Interquartile Range (IQR) 17, minimum 18, maximum 62 years old, with 177 (52.1%) females. The majority were single 207 (64.7%), 57 (18.0%) married, co-habiting 38 (11.9%), separated 15 (4.7%), divorced 3 (0.9%), and n = 20 did not give this information (missing data). Regarding the employment status, most of them were currently employed 138 (42.8%), unemployed 94 (29.6%), students 84 (26.4%), few retired 4 (1.3%) and 22 were missing data. The highest educational level achieved was, none 5 (1.6%), junior certificate 5 (1.8%) leaving certificate 160 (51.9%), vocational diploma 24 (7.8%), other diplomas 20 (6.5%), non-university degree (Institutes of Technology) 27 (8.8%), and university degree/postgraduate degree 67 (21.8%). Table 1 shows those demographics separately for those diagnosed with ADHD and those without an ADHD diagnosis, who did not.

ADHD diagnosis

Using the DIVA 5 and clinical psychiatric evaluation (based on DSM-5 criteria) 293 participants (86.2%) met criteria for ADHD diagnosis and 47 (13.8%) did not. The reasons for non-diagnosis were because either the number of symptoms was subthreshold, or the age of onset of symptoms was later than the 13 years old or the symptoms were better explained by another mental disorder. From those diagnosed with ADHD, the majority were diagnosed with combined subtype (n = 169, 57.7%), inattentive subtype (n = 117, 39.9%) and few with hyperactive/impulsive subtype (n = 7, 2.4%).

Functional impairment and quality of life (WFIRS, AAQoL, GAF)

The descriptive statistics of these three scales and their subscales are presented separately for those diagnosed with ADHD and those not diagnosed (Table 2). The median and the IQR are also given as the GAF was not normally distributed. It can be seen in Table 2 that people with ADHD have lower QoL from the midpoint of the scale (50). The functionality as measured by the WFIRS and GAF, was a little better than the midpoints of the scales (1.5 and 50 respectively), indicated substantial functional impairment overall.

Bivariate statistics

Correlation between GAF and WFIRS

GAF demonstrated a significant corelation with total WFIRS (Spearman’s r = − 0.312, p < 0.001) as well as with its subscales (family, r = − 0.224, p < 0.001; work r = − 0.295, p < 0.001 school, r = − 0.300, p < 0.001; life-skills r = − 0.127, p = 0.043; self-concept, r = − 0.140, p = 0.030: social, r = − 0.256, p < 0.001; risk, r = − 0.168, p = 0.008).

Comparison between those diagnosed with and without ADHD on demographic characteristics

No differences were found between those two groups regarding age (Mann–Whitney U = 6681.0, z = − 0.327, p = 0.744), gender (x2 = 0.213, df:1, p = 0.644), marital status, employment status and level of education using x2 tests (see Table 1).

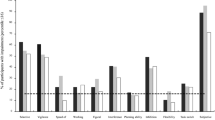

Comparison between those diagnosed with and without ADHD on each of the three scales (WFIRS, AAQoL, GAF)

Table 3 (t-tests) shows the results from those comparisons of the total scales and their subscales. Those diagnosed with ADHD had worse functional impairment (WFIRS) and worse quality of life compared to those without ADHD. Because GAF was not normally distributed the Mann–Whitney test was used for the comparison. Similarly, those with ADHD had significantly worse functioning as measured with the GAF compared to those without (Mann–Whitney U = 3562.5, z = − 3.115, p = 0.002).

Functional impairment and quality of life among the ADHD subtypes

Finally, ANOVA tests with Bonferroni corrections were applied for the normally distributed variables (WFIRS and AAQoL) and Kruskal–Wallis test for GAF to find out if there were differences in the functional impairment and quality of life among the subtypes. The results for WFIRS and AAQoL are presented in Table 4. Those with combined subtype have significantly worse functioning compared to those with hyperactive/impulsive or inattentive subtype but no significant difference between hyperactive/impulsive and inattentive subtype. Similarly, those with combined subtype have worse quality of life compared to hyperactive/impulsive but no difference compared to inattentive subtype. Regarding the GAF the Kruskal–Wallis test did not show any significant difference among the groups (Kruskal–Wallis H = 2.343, df:2, p = 0.340).

Post hocpower calculations

For the comparisons between those diagnosed with and without ADHD (t-tests) the outcome variable WFIRS had a power of 0.833 to detect true difference the AAQoL a power of 0.686 and for the GAF the observed power was 0.90.

For the last analysis (ANOVA tests), a power calculation was performed for each of the two variables (WFIRS and AAQoL). For the WFIRS, the power to detect true differences was 0.981 and for AAQoL 0.830. For the comparison between the groups Combined subtype vs. Hyperactive/Impulsive for the WFIRS, the power was 0.965 and for the AAQoL was 0.841.

Discussion

The results above show that adults newly diagnosed with ADHD have low QoL and substantial functional impairment as measured by the AAQoL and WFIRS. The impairments in the QoL of individuals with ADHD as well as of their family (parents) are a frequent finding in previous studies which have mainly focused on children and adolescents with ADHD. A meta-analysis of 7 studies in people with ADHD showed greater impairment in QoL compared to those with a normal development [31] and another meta-analysis [32] of 17 studies showed that the parents of children with ADHD had reduced QoL. To date, there is no specific meta-analysis for adults, however, the few studies which investigate QoL in adults with ADHD reported similar results with the present study [11, 12]. It was suggested that the QoL in adults with ADHD is related to developmental impairment in executive function (EF) [33] while impaired EF has also been demonstrated to predict depression [34], a common comorbidity in adults with ADHD. In a more recent study [35] showed that ADHD could affect QoL in a cumulative manner indirectly via EF in addition to the negative impact of depressive/anxiety symptoms on QoL. It is reasonable to hypothesise that the long-standing symptomatology of ADHD combined with varied combinations of comorbidities suboptimal coping mechanisms, repeated experience of challenge and failure in the everyday life, underachievement, may contribute in a cumulative fashion to low QoL. It is worth noting that in this study the participants’ AAQoL total mean score (38.35) was lower than reported in other studies [23, 25, 33]. However, it is reasonable to assert that the participants in our study have long standing disorder unmedicated and untreated and perhaps with more severe consequences given that the vast majority were diagnosed for the first time in their adulthood, (the time that they participated in the study), and thus had not previously accessed ADHD treatment. In addition, given that this patient cohort was referred from general adult mental health teams, they may have had more comorbidities relative to cohorts in previous studies.

Similarly, the functional impairment (WFIRS) in the investigated sample was relatively lower than the midpoint, but a range of other functional outcomes was also impaired (low employment rate, low educational level, majority single) illuminating the sequelae of unrecognised and untreated ADHD in relation to work, educational attainment and relationships. These findings are in accordance with previous studies [11, 36, 37]. A number of studies which examined the EF of adults with ADHD proposed that impairment of EF partly explain the educational and occupational problems [7, 38], but some other studies contradict this suggestion [11]. However, ADHD is characterised by heterogeneous cognitive profiles, which can and do change across time [39, 40]. Therefore, the suggestion of a direct or indirect link between EF and functional impairment is rather premature and needs to be investigated further particularly with longitudinal studies.

The results of this study also demonstrate that adults with ADHD with similar sociodemographic variable as those who have symptoms of ADHD but do not meet the criteria for diagnosis, have lower levels of QoL and functionality. A previous study by Pawaskar [41] reported contradictory findings with the present study; however, it is worth noting that there were major methodological differences between the two studies. Pawaskar et al.’s study, comprised a bigger sample but was based mainly on self-reported diagnoses with no clinical evaluation performed. In our study, both groups were comprehensively clinically evaluated. If our results are replicated in further studies, it may indicate that the symptoms of ADHD in and of themselves are not the only explanation for the low QoL and impaired functioning evident in adult ADHD. Rather, it is reasonable to infer that the early onset ADHD during critical developmental phases in childhood adversely affects developmental trajectories including suboptimal coping, social, and educational outcomes, thereby lowering functional capacity and worsening QoL in the adulthood [42].

In addition, our results indicate that there are differences in the levels of QoL and functionality among the ADHD subtypes. Those with combined subtype have significantly worse functioning compared to those with hyperactive/impulsive and to those with inattentive subtype but this significance remains only for the hyperactive/impulsive when the QoL examined. Only a small number of studies in adults have specifically examined the ADHD-subtypes in relation to functional impairment and QoL. An early study[43], reported similar results to ours, regarding functional impairment and QoL, with two more studies examining functional impairment alone reporting similar results [44, 45]. In children and adolescents, there are more studies which have explored functional impairment and ADHD subtype, with similar results reported [46, 47]. Given that the combined subtype includes both symptom clusters relating to inattention and hyperactivity it may be reasonable to predict that functionality and QoL would be more negatively impacted. It is worth highlighting that the number of hyperactive/impulsive subtype is small (n = 7, 2.4%); however, this is in keeping with expected rate in adulthood and even in childhood the rate of hyperactive/impulsive subtype is low, estimated at 6 to 8% of the total ADHD population [43]. Given that hyperactivity is reduced with age, it is likely that the prevalence of hyperactive/impulsive subtype in our sample is representative and with adequate power to detect true difference.

It is worth also to comment here about the gender distribution. ADHD is considered mainly as a disorder frequent in males than females especially in childhood and adolescent, with a reported male to female ratio of 3:1 to 9:1 [48]. More recent studies narrow this gap [49]. However, in adult ADHD the rate of male female is higher for females. Previous studies in adult referred populations for ADHD shows similar rates with the present study [3, 50]. Among the explanations that have been suggested for this reverse rate in adulthood are that in childhood the over representation of males may reflect under diagnosis in females, which somewhat correct itself, with the likelihood of females being more likely than males to seek out treatment as an adult (referral bias), genetic vulnerability, endocrine factors, psychosocial contributors, increased levels of remission of symptoms of ADHD in males, or late onset of ADHD more prominent in females [51, 52].

Finally, our results demonstrate a significant corelation between WFIRS and GAF although this corelation is weak (31%). A higher corelation (moderate) was reported from a previous study in which WFIRS, translated to Japanese, was evaluated [53]. The concurrent validity of those two scales was not among our primary aims for the present study, but searching the literature it was found that GAF has been used in adult ADHD as an objective measurement of functioning by clinicians. WFIRS is designed specifically for populations with ADHD, and it is a self-reported scale. This weak correlation can be explained from the different construct that those two scales used and measured. GAF is more restrictive to psychological, occupational, and social impairment, while WFIRS is broader and examined seven domains of functioning. Besides the WFIRS is a self-reported scale and self-biases are possible [54].

Limitations of the study

Although the sample was adequate with high observed power the comparison group of participants with ADHD-like symptoms was relatively small to allow firm conclusions especially for the AAQL scale (observed power 68.6%). Similarly, the sample of hyperactive/impulsive subtype was small as discussed above; however, as noted, the rate was similar to what it was expected in an adult population and thus likely to be representative and with a good power to detect true difference. A final limitation is the generalizability of the results. The sample was from an Irish special adult ADHD clinic in which there are certain guidelines for referrals. Therefore, the results can apply in similar settings but perhaps not in other settings which use different systems of referrals.

In summary, in this study we found that adults with ADHD have impaired functionality and low quality of life. Those with combined type ADHD have more functional impairment compared to the other two subtypes and worse QoL compared to hyperactive/impulsive subtype. Low QoL and functional impairment in those with ADHD are significantly worse compared to those with ADHD-like symptoms but no diagnosis of ADHD. This reinforces the view that ADHD is not just a behavioural disorder in childhood, but a lifelong condition with accumulating problems and symptoms that can lead to persistent difficulties throughout adulthood.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DA, upon reasonable request.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.)

Simon V, Czobor P, Balint S et al (2009) Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 194:204–211. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048827194/3/204[pii]

Adamis D, Flynn C, Wrigley M et al (2022) ADHD in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies in outpatient psychiatric clinics. J Atten Disord 26:1523–1534. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547221085503

Turgay A, Goodman DW, Asherson P et al (2012) Lifespan persistence of ADHD: the life transition model and its application. J Clin Psychiatry 73:192–201. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06628

Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM et al (2022) Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry 179:142–151. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032

Miranda A, Berenguer C, Colomer C, Rosello R (2014) Influence of the symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and comorbid disorders on functioning in adulthood. Psicothema 26:471–476. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.121

Holst Y, Thorell LB (2020) Functional impairments among adults with ADHD: a comparison with adults with other psychiatric disorders and links to executive deficits. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 27:243–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2018.1532429

Mohamed SMH, Borger NA, van der Meere JJ (2021) Executive and daily life functioning influence the relationship between ADHD and mood symptoms in university students. J Atten Disord 25:1731–1742. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054719900251

WHOQOL (1995) The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 41:1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k

Schworer MC, Reinelt T, Petermann F, Petermann U (2020) Influence of executive functions on the self-reported health-related quality of life of children with ADHD. Qual Life Res 29:1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02394-4

Orm S, Oie MG, Fossum IN et al (2023) Predictors of quality of life and functional impairments in emerging adults with and without ADHD: a 10-year longitudinal study. J Atten Disord 27:458–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547231153962

Quintero J, Morales I, Vera R et al (2019) The impact of adult ADHD in the quality of life profile. J Atten Disord 23:1007–1016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717733046

Adler LA, Dirks B, Deas P et al (2013) Self-reported quality of life in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and executive function impairment treated with lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. BMC Psychiatry 13:253. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-253

Di Lorenzo R, Balducci J, Poppi C et al (2021) Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: a systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr 33:283–298. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2021.23

Elliott J, Johnston A, Husereau D et al (2020) Pharmacologic treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15:e0240584. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240584

HSE (2020) ADHD in adults national clinical programme: model of care for Ireland. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/mental-health/adhd/adhd-in-adults-ncp-model-of-care/adhd-in-adults-ncp-model-of-care.pdf.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M et al (2005) The World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med 35:245–256

Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW (1993) The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 150:885–890. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.150.6.885

Ramos-Quiroga JA, Nasillo V, Richarte V et al (2019) Criteria and concurrent validity of DIVA 2.0: a semi-structured diagnostic interview for adult ADHD. J Atten Disord 23:1126–1135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716646451

Weiss M (2015) Functional impairment in ADHD. In: Adler LASTJ, Wilens TE (eds) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults and children. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. UK, pp 42–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139035491.005

Canu WH, Hartung CM, Stevens AE, Lefler EK (2020) Psychometric properties of the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale: evidence for utility in research, assessment, and treatment of ADHD in emerging adults. J Atten Disord 24:1648–1660. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716661421

Weiss MD, McBride NM, Craig S, Jensen P (2018) Conceptual review of measuring functional impairment: findings from the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale. Evid Based Ment Health 21:155–164. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300025

Brod M, Adler LA, Lipsius S et al (2015) Validation of the adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder quality-of-life scale in European patients: comparison with patients from the USA. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 7:141–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-014-0160-z

Gjervan B, Torgersen T, Hjemdal O (2019) The Norwegian translation of the Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Quality of Life Scale: validation and assessment of QoL in 313 adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 23:931–939. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716640087

Matza LS, Van Brunt DL, Cates C, Murray LT (2011) Test-retest reliability of two patient-report measures for use in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 15:557–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054710372488

Luborsky L (1962) Clinician’s judgments of mental health. Arch Gen Psychiatry 7:407–417. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1962.01720060019002

Pedersen G, Karterud S (2012) The symptom and function dimensions of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale. Compr Psychiatry 53:292–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.04.007

Jones SH, Thornicroft G, Coffey M, Dunn G (1995) A brief mental health outcome scale-reliability and validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). Br J Psychiatry 166:654–659. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.166.5.654

Schwartz RC (2007) Concurrent validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale for clients with schizophrenia. Psychol Rep 100:571–574. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.100.2.571-574

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39:175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

Lee YC, Yang HJ, Chen VC et al (2016) Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: by both parent proxy-report and child self-report using PedsQL. Res Dev Disabil 51–52:160–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.009

Dey M, Paz Castro R, Haug S, Schaub MP (2019) Quality of life of parents of mentally-ill children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 28:563–577. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796018000409

Stern A, Pollak Y, Bonne O et al (2017) The relationship between executive functions and quality of life in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 21:323–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713504133

Knouse LE, Barkley RA, Murphy KR (2013) Does executive functioning (EF) predict depression in clinic-referred adults? EF tests vs. rating scales. J Affect Disord 145:270–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.064

Zhang SY, Qiu SW, Pan MR et al (2021) Adult ADHD, executive function, depressive/anxiety symptoms, and quality of life: a serial two-mediator model. J Affect Disord 293:97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.020

Gjervan B, Torgersen T, Nordahl HM, Rasmussen K (2012) Functional impairment and occupational outcome in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 16:544–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711413074

Uchida M, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV, Biederman J (2018) Adult outcome of ADHD: an overview of results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of pediatrically and psychiatrically referred youth with and without ADHD of both sexes. J Atten Disord 22:523–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715604360

Halleland HB, Sorensen L, Posserud MB et al (2019) Occupational status is compromised in adults with ADHD and psychometrically defined executive function deficits. J Atten Disord 23:76–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054714564622

Guo N, Fuermaier ABM, Koerts J et al (2021) Neuropsychological functioning of individuals at clinical evaluation of adult ADHD. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 128:877–891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-020-02281-0

Kosheleff AR, Mason O, Jain R et al (2023) Functional impairments associated with ADHD in adulthood and the impact of pharmacological treatment. J Atten Disord 27:669–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547231158572

Pawaskar M, Fridman M, Grebla R, Madhoo M (2020) Comparison of quality of life, productivity, functioning and self-esteem in adults diagnosed with ADHD and with symptomatic ADHD. J Atten Disord 24:136–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054719841129

Adamis D, Fox N, de MdCAPP SF et al (2023) Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in an adult mental health service in the Republic of Ireland. Int J Psychiatry Med 58:130–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/00912174221106826

Gibbins C, Weiss MD, Goodman DW et al (2010) ADHD-hyperactive/impulsive subtype in adults Ment Illn 2:e9. https://doi.org/10.4081/mi.2010.e9

Mak ADP, Chan AKW, Chan PKL et al (2020) Diagnostic outcomes of childhood ADHD in Chinese adults. J Atten Disord 24:126–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718802015

Sobanski E, Bruggemann D, Alm B et al (2008) Subtype differences in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with regard to ADHD-symptoms, psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial adjustment. Eur Psychiatry 23:142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.09.007

Meyer J, Alaie I, Ramklint M, Isaksson J (2022) Associated predictors of functional impairment among adolescents with ADHD-a cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 16:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-022-00463-0

Willcutt EG, Nigg JT, Pennington BF et al (2012) Validity of DSM-IV attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom dimensions and subtypes. J Abnorm Psychol 121:991–1010. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027347

Gaub M, Carlson CL (1997) Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:1036–1045. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199708000-00011

Rucklidge JJ (2010) Gender differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 33:357–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.006. (S0193–953X(10)00021–3 [pii])

Ahnemark E, Di Schiena M, Fredman AC et al (2018) Health-related quality of life and burden of illness in adults with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Sweden. BMC Psychiatry 18:223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1803-y

Ginsberg Y, Quintero J, Anand E et al (2014) Underdiagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adult patients: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.13r01600

Young S, Adamo N, Asgeirsdottir BB et al (2020) Females with ADHD: an expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry 20:404. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02707-9

Takeda T, Tsuji Y, Kanazawa J et al (2017) Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale: self-report. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 9:169–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-016-0213-6

Fuermaier ABM, Tucha O, Koerts J et al (2018) Susceptibility of functional impairment scales to noncredible responses in the clinical evaluation of adult ADHD. Clin Neuropsychol 32:671–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1406143

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adamis, D., West, S., Singh, J. et al. Functional impairment and quality of life in newly diagnosed adults attending a tertiary ADHD clinic in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-024-03713-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-024-03713-6