Abstract

Objective

Cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) intervention enhances the psychological status and quality of life in patients with various diseases, such as cancer, human immunodeficiency virus infection, chronic fatigue syndrome, and multiple sclerosis. This multicenter, randomized, controlled study intended to explore the potential benefit of CBSM in ameliorating the anxiety, depression, and quality of life (QoL) in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods

A total of 250 AMI patients who received PCI were randomly allocated to the CBSM (N = 125) and control care (CC) (N = 125) groups, and underwent weekly corresponding interventions for 12 weeks. The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D), and EuroQol visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) scores were evaluated at baseline (M0), month (M)1, M3, and M6. Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were recorded during follow-up.

Results

HADS-anxiety score at M1 (P = 0.036), M3 (P = 0.002), and M6 (P = 0.001), as well as anxiety rate at M6 (P = 0.026), was reduced in the CBSM group versus the CC group. HADS-depression score at M3 (P = 0.027) and M6 (P = 0.002), as well as depression rate at M6 (P = 0.013), was decreased in the CBSM group versus the CC group. EQ-5D score at M3 (P = 0.046) and M6 (P = 0.001) was reduced, while EQ-VAS score at M1 (P = 0.037), M3 (P = 0.010), and M6 (P = 0.003) was raised, in the CBSM group versus the CC group. However, accumulating MACE rate did not differ between the two groups (P = 0.360).

Conclusion

CBSM ameliorates anxiety, depression, and QoL but does not affect MACE in AMI patients after PCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a crucial cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, which is divided into ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-STEMI (NSTEMI) [1]. The global incidence of AMI varies across different regions and is influenced by various factors such as age, gender, and lifestyle [2]. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is an efficacious treatment option for AMI, and its application has improved the prognosis of AMI patients to a certain extent [3]. Unfortunately, disease recurrence and other major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) would also happen in AMI patients even after successful PCI [4,5,6]. It is estimated that the incidence of recurrent AMI after PCI within 3 years ranges from 3.6 to 6.9% [4, 7], and the incidence of MACE after PCI within 2 years ranges from 9.7 to 16.5% [8,9,10]. The worry of AMI, as well as the fear of disease recurrence and MACE, places a tremendous psychological burden (such as anxiety and depression) and affects the quality of life in AMI patients who undergo PCI, which may further influence their clinical outcomes [11,12,13,14]. As a result, exploring potential interventions to enhance the psychological status and quality of life in AMI patients who undergo PCI is necessary.

Cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) is a type of psychotherapeutic intervention, which helps people learn how to deal with destructive thoughts or negative emotions [15, 16]. In the recent decade, CBSM has been disclosed to have a certain benefit to ameliorate mental health and the quality of life in patients with various diseases, such as cancers, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and chronic fatigue syndrome [16,17,18,19]. Unfortunately, evidence regarding the benefit of CBSM intervention on attenuating anxiety and depression, along with increasing the quality of life in heart disease patients, is scarce. The only existing study reports that CBSM intervention not only reduces fear of recurrence and stress levels but also improves well-being in atrial fibrillation patients [20]. However, the potential benefit of CBSM intervention in AMI patients who receive PCI has not been studied yet and deserves investigation.

Accordingly, the current research aimed to investigate the implication of CBSM intervention in relieving anxiety and depression, along with enhancing the quality of life in AMI patients who received PCI.

Methods

Patients

In this randomized, controlled study, two hundred and fifty AMI patients who received PCI treatment between February 2020 and June 2022 were enrolled, and the treatment of PCI for AMI patients is following a guideline [21]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosis with AMI according to the 3rd universal definition of myocardial infarction (MI) [22], (2) aged > 18 years, (3) had the ability to complete assessments, (4) willing to cooperate with the completion of the questionnaire related to this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) with malignant diseases, (2) with a severe mental disorder or cognitive impairment that could not communicate normally. The Ethics Committee approved this study. Informed consent was collected from each patient.

Data collection and randomization

Clinical features of AMI patients were collected, which included demographics, history of chronic diseases, disease-related information, laboratory tests, and PCI-related information. After enrollment, all patients were randomly assigned into the CBSM or control care (CC) groups using a 1:1 ratio. The randomization was conducted by the block randomization method (bloke size = 4). Random grouping information for each patient was sealed in an opaque envelope, and which patient’s ID was written on the cover. In chronological order of patient enrollment, the patient was given the opaque envelope and allocated to two different groups.

Care intervention

After randomization, the interventions were carried out by the trained nurses on both CC and CBSM groups for 12 weeks in a team form (8–10 patients per team). Patients assigned to teams based on the order of discharge time and group information. Each intervention was lasted 120 min, and was conducted on the morning of the first Saturday of each week by trained nurses. Notably, the day before each intervention, trained nurses at their respective centers would inform the time and place of the interventions by sending short message service (SMS) texts and emails to remind patients. If patients were initially unresponsive, the trained nurses would subsequently remind them by telephone. In addition, there was no uniform location for the intervention; the patients participated in the intervention at their corresponding centers.

For the CC group, the intervention contained a 60-min presentation centered on education related to basic knowledge of AMI, postoperative care, rehabilitation, diet, and physical exercise. Following that, a 30-min question-and-answer session and another 30-min free time were conducted.

For the CBSM group, after a 60-min presentation with the same content as the CC group, a specific intervention including a 30-min CBSM skills-teach session and another 30-min CBSM-based relaxation training session was followed. In brief, the 30-min CBSM skills-teach session mainly included the following aspects: (1) stress identification and cognitive reconstruction, which was developed by guiding and encouraging patients to talk about their current problems and stresses; (2) emotion management and confidence building, which was developed by guiding patients to express their emotional changes and the reasons. Besides, the 30-min CBSM-based relaxation training session included deep breathing, meditation, and muscle relaxation.

Evaluation

The hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) score, EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D) score, and EuroQol visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) score were evaluated at baseline (M0), 1st month (M1), 3rd month (M3), and 6th month (M6). The HADS score was used to evaluate patients’ anxiety and depression, which was scaled from 0 to 21 for each aspect (the higher the worse) [23]. The HADS was a Chinese version, and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for total scale, HADA-anxiety (HADS-A), and HADS-depression (HADS-D) was 0.945, 0.921, and 0.932, respectively [24]. The EQ-5D and EQ-VAS scores were applied to evaluate the quality of life, in which EQ-5D score ranged from 5 to 15 (the higher the worse) and EQ-VAS score ranged from 0 to 100 (the higher the better) [25]. The EQ-5D and EQ-VAS was also a Chinese version, and the ICC for EQ-5D and EQ-VAS was 0.79 and 0.80, respectively [26]. Besides, patients also underwent routine follow-ups for 6 months, and MACE was recorded, which was defined as cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, unplanned coronary revascularization, and hospital admission for cardiovascular cause [27]. The primary outcome in this study was the HADS-A score assessed at M6. The secondary outcomes included HADS-D score at M6, EQ-5D score at M6, EQ-VAS score at M6, and MACE.

Statistics

According to clinical experience, the sample size calculation was performed per the hypothesis that the mean HADS-A at M6 in the CBSM group was 6, while the mean HADS-A at M6 in the CC group was 7. The standard deviation (SD) was supposed as 2.3. With the significance (α) level of 0.05 and the power of 85%, the minimum sample size was 96 for each group and then adjusted to 125 considering the drop-out possibility of 20%. Comparisons between the two groups were assessed by the student t-test and χ2 test. The Kaplan–Meier curve was used to show accumulating MACE rate, and log-rank test was utilized for comparing the difference between two groups. P < 0.05 indicated significance. SPSS v.26.0 (IBM, USA) was used for data processing and GraphPad Prism v.7.0 (GraphPad Software, USA) was used for figure plotting.

Results

Study flow

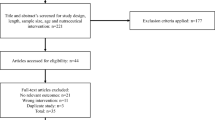

Initially, 265 AMI patients who received PCI were screened, and 15 patients were excluded, containing 8 patients who failed to meet the inclusion criteria, 4 patients who met the exclusion criteria, and 3 patients who refused to participate. Then, 250 patients were included and randomly allocated to CC and CBSM groups in a 1:1 ratio. In the CC group (N = 125), patients received CC intervention for 12 weeks, and 12 (9.6%) patients dropped out, including 8 (6.4%) patients who lost contact, 2 (1.6%) patients who were not willing to continue to participate in this study, and 2 (1.6%) patients who died. In the CBSM group (N = 125), patients received CBSM intervention for 12 weeks as well, and 17 (13.6%) patients dropped out, including 11 (8.8%) patients who lost contact, 5 (4.0%) patients who were not willing to continue to participate in this study, and 1 (0.8%) patient who died. Patients in both groups were followed up until M6. The HADS-A score, HADS-D score, EQ-5D score, and EQ-VAS score were assessed at M0, M1, M3, and M6. All patients were included in the analysis with the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle (Fig. 1).

Clinical characteristics of CBSM and CC groups

The mean ages of the CBSM group and the CC group were 62.8 ± 10.2 years and 63.6 ± 9.7 years, respectively (P = 0.525). Meanwhile, there were 38 (30.4%) females and 87 (69.6%) males in the CBSM group, as well as 30 (24.0%) females and 95 (76.0%) males in the CC group (P = 0.256). Other clinical features were not different between the two groups either (all P > 0.05). Notably, HADS-A, HADS-D, EQ-5D, and EQ-VAS scores at baseline were also not different between the two groups (all P > 0.05). Specific clinical information of AMI patients who received PCI is listed in Table 1.

Comparison of anxiety and depression between CBSM and CC groups

The HADS-A score at M0 was not different between the two groups (P = 0.601). However, the HADS-A score at M1 (6.9 ± 2.5 vs. 7.5 ± 2.4) (P = 0.036), M3 (6.3 ± 2.2 vs. 7.3 ± 2.4) (P = 0.002), and M6 (6.1 ± 1.9 vs. 7.0 ± 2.3) (P = 0.001) was decreased in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (Fig. 2A). The anxiety rate at M0 (P = 0.610) and M1 (P = 0.302) did not differ between the two groups, while the anxiety rate at M3 also displayed a decreasing trend in the CBSM group vs. the CC group but did not achieve statistical significance (25.0% vs. 35.8%) (P = 0.071). Notably, the anxiety rate at M6 was decreased in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (21.1% vs. 34.5%) (P = 0.026) (Fig. 2B).

Anxiety in the CBSM group and the CC group. Comparison of HADS-A score at M0, M1, M3, and M6 between the CBSM group and the CC group (A); comparison of anxiety rate at M0, M1, M3, and M6 between the CBSM group and the CC group (B). The comparisons of HADS-A score and anxiety rate between the two groups were assessed by the student t-test and χ2 test, respectively

The HADS-D score at M0 (P = 0.685) and M1 (P = 0.209) was not different between the two groups. Nevertheless, the HADS-D score at M3 (6.7 ± 2.3 vs. 7.4 ± 2.6) (P = 0.027) and M6 (6.3 ± 1.9 vs. 7.3 ± 2.5) (P = 0.002) was reduced in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (Fig. 3A). The depression rate at M0 (P = 0.898) and M1 (P = 0.532) was not different between the two groups. However, the depression rate at M3 showed a decreasing trend in the CBSM group vs. the CC group but lacked statistical significance (30.2% vs. 41.7%) (P = 0.066). Importantly, the depression rate at M6 was declined in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (22.0% vs. 37.3%) (P = 0.013) (Fig. 3B).

Depression in the CBSM group and the CC group. Comparison of HADS-D score at M0, M1, M3, and M6 between the CBSM group and the CC group (A); comparison of depression rate at M0, M1, M3, and M6 between the CBSM group and the CC group (B). The comparisons of HADS-D score and depression rate between the two groups were assessed by the student t-test and χ2 test, respectively

Comparison of quality of life between CBSM and CC groups

The EQ-5D score at M0 (P = 0.522) and M1 (P = 0.149) did not differ between the two groups, while the EQ-5D score at M3 (8.1 ± 1.8 vs. 8.6 ± 1.6) (P = 0.046) and M6 (7.6 ± 1.6 vs. 8.3 ± 1.4) (P = 0.001) was decreased in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (Fig. 4A). The EQ-VAS score at M0 was not different between the two groups (P = 0.571). However, the EQ-VAS score at M1 (73.2 ± 14.7 vs. 69.3 ± 14.8) (P = 0.037), M3 (78.5 ± 13.0 vs. 74.3 ± 12.2) (P = 0.010), and M6 (82.3 ± 13.7 vs. 76.8 ± 13.0) (P = 0.003) was raised in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (Fig. 4B).

Quality of life in the CBSM group and the CC group. Comparison of EQ-5D score at M0, M1, M3, and M6 between the CBSM group and the CC group (A); comparison of EQ-VAS score at M0, M1, M3, and M6 between the CBSM group and the CC group (B). The comparisons of EQ-5D score and EQ-VAS score between the two groups were assessed by the student t-test

Subgroup analysis of anxiety, depression, and quality of life at M6

In patients without anxiety at M0, only the EQ-VAS score at M6 was raised in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (P = 0.039). Notably, in patients with anxiety at M0, the HADS-A score, anxiety rate, HADS-D score, depression rate, and EQ-5D score at M6 were decreased but the EQ-VAS score at M6 was elevated in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (all P < 0.05) (Table 2).

In patients without depression at M0, only the EQ-5D score at M6 was declined in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (P = 0.018). Importantly, in patients with depression at M0, the HADS-A score, anxiety rate, HADS-D score, depression rate, and EQ-5D score at M6 were reduced, while the EQ-VAS score at M6 was raised in the CBSM group vs. the CC group (all P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Regarding marital status, in married patients, HADS-A score (P = 0.003), HADS-D score (P = 0.002), and EQ-5D score (P = 0.001) at M6 were all decreased, but EQ-VAS score (P = 0.017) at M6 was increased in the CBSM group compared to the CC group. In single/divorced/widowed patients, HADS-A score, HADS-D score, EQ-5D score, and EQ-VAS score at M6 were not different between the two groups (all P > 0.05).

In terms of employment status, in unemployed patients, HADS-A score (P = 0.001), HADS-D score (P = 0.023), and EQ-5D score (P = 0.002) at M6 were all decreased, but EQ-VAS score (P = 0.009) at M6 was increased in the CBSM group compared to the CC group. In employed patients, only HADS-D score at M6 was decreased in the CBSM group versus the CC group (P = 0.015).

With respect to education level, in patients with an education level of primary school or below, EQ-5D score at M6 (P = 0.024) was decreased but EQ-VAS score at M6 (P = 0.030) was increased in the CBSM group compared to the CC group. In patients with an education level of middle or high school, HADS-A score at M6 was decreased in the CBSM group compared to the CC group (P = 0.005). In patients with an education level of undergraduate or above, HADS-D score (P = 0.040) and EQ-5D score (P = 0.015) at M6 were deceased but EQ-VAS score (P = 0.018) at M6 was increased in the CBSM group versus the CC group (Supplementary Table 1).

Comparison of accumulating MACE rate between CBSM and CC groups

During the 6-month follow-up, MACE was recorded in the CBSM group and the CC group. It was found that accumulating MACE rate during 6 months was 3.2% in the CBSM group, and it was 5.6% in the CC group. Notably, accumulating MACE rate was not different between the two groups (P = 0.360) (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Anxiety and depression are prevalent in heart disease patients, which may lead to prolonged hospitalization and increased mortality in these patients [11, 28, 29]. The current study found that CBSM intervention reduced anxiety and depression in AMI patients who received PCI compared to CC intervention. The potential reasons would be that (1) CBSM intervention guided and encouraged patients to share their current worries and stresses with others, which was beneficial to relieve anxiety and depression [30, 31]. (2) CBSM intervention helped patients to manage their emotional problems and build their confidence by expressing their troubles with other participants, which was helpful to establish supportive relationships with others and increase their confidence, thereby attenuating anxiety and depression [30]. (3) The relaxation training session of CBSM intervention allowed patients to refresh their minds, eliminate fatigue, and regain strength, which would further result in the reduction of anxiety and depression [32, 33].

Apart from anxiety and depression, reduced quality of life is also a crucial problem in heart disease patients [34]. However, most of the studies mainly focus on the potential of cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention and discover that this intervention improves the quality of life in coronary artery disease patients receiving PCI and heart failure patients [30, 35]. Nevertheless, the potential of CBSM intervention in enhancing the quality of life in AMI patients who undergo PCI needs exploration. The current study discovered that CBSM intervention increased the quality of life in AMI patients who received PCI vs. CC intervention. The reasons behind this might be that (1) anxiety or depression was a crucial dimension to evaluate the quality of life; as discussed above, anxiety and depression were attenuated by CBSM intervention, which might directly or indirectly assist in ameliorating the quality of life in AMI patients who received PCI [30, 32, 33]; (2) CBSM intervention also contained skills-teach session and relaxation training session, which might help to build social relationships with others, increase confidence, relieve stresses, and restore health status, thereby enhancing the quality of life [36]. Taken together, quality of life could be improved by CBSM intervention in AMI patients who underwent PCI.

Interestingly, the subgroup analysis found that patients with anxiety and depression at baseline might be benefited more from CBSM intervention in attenuating anxiety and depression, along with enhancing the quality of life at M6. The potential arguments might be that patients with anxiety and depression at baseline had severe psychological conditions; thus, the benefit of CBSM intervention might be stronger; in addition, patients could learn about this intervention after months; thus, they could conduct this intervention in their daily life, resulting in the reduction of anxiety and depression, and the enhancement of the quality of life at M6 [37, 38]. Notably, the current study also discovered that accumulating MACE was not affected by CBSM in AMI patients who underwent PCI. The speculation would be that limited by the follow-up duration, the occurrence rates of MACE were low, and the benefit of CBSM intervention might need a longer time to realize. Taken together, the benefit of CBSM intervention in MACE was not obvious in AMI patients who received PCI.

Although several interesting findings had been revealed, the limitations could not be omitted. Firstly, the long-term benefit of CBSM intervention in reducing anxiety and depression, along with ameliorating the quality of life in AMI patients who underwent PCI should be further explored. Secondly, the HADS score, EQ-5D score, and EQ-VAS score were self-assessed, which might lead to assessment bias. Thirdly, some individual-based psychotherapeutic interventions had been reported to improve mental health and quality of life [39,40,41]; however, in this study, the CBSM intervention was carried out in a group setting, and the impact of the individual-based CBSM intervention on enhancing mental condition and the quality of life in AMI patients who received PCI was unknown and could be further explored. Fourthly, the follow-up duration was short; thus, the potential of CBSM intervention on reducing MACE in AMI patients who underwent PCI should be explored by further studies with a longer follow-up duration.

In conclusion, CBSM is a potential intervention in ameliorating anxiety, depression, and quality of life but does not affect MACE in AMI patients who undergo PCI. More shreds of evidence are required to validate the findings of this study.

References

Reed GW, Rossi JE, Cannon CP (2017) Acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 389(10065):197–210

Bradley SM, Borgerding JA, Wood GB et al (2019) Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes associated with in-hospital acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Netw Open 2(1):e187348

Hoole SP, Bambrough P (2020) Recent advances in percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart 106(18):1380–1386

Lee SH, Jeong MH, Ahn JH et al (2022) Predictors of recurrent acute myocardial infarction despite successful percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean J Intern Med 37(4):777–785

Kikkert WJ, Hoebers LP, Damman P et al (2014) Recurrent myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 113(2):229–235

Jortveit J, Pripp AH, Langorgen J, Halvorsen S (2020) Incidence, risk factors and outcome of young patients with myocardial infarction. Heart 106(18):1420–1426

Stone SG, Serrao GW, Mehran R et al (2014) Incidence, predictors, and implications of reinfarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: the Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 7(4):543–551

Zhu Y, Zhang JL, Yan XJ et al (2022) Effect of dapagliflozin on the prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Diabetol 21(1):186

Piestrzeniewicz K, Luczak K, Goch JH (2008) Value of blood adipose tissue hormones concentration–adiponectin, resistin and leptin in the prediction of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in 1-year follow-up after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 29(4):581–588

Park H, Hong YJ, Cho JY et al (2017) Blood pressure targets and clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J 47(4):446–454

Liblik K, Mulvagh SL, Hindmarch CCT et al (2022) Depression and anxiety following acute myocardial infarction in women. Trends Cardiovasc Med 32(6):341–347

Sreenivasan J, Kaul R, Khan MS et al (2022) Mental health disorders and readmissions following acute myocardial infarction in the United States. Sci Rep 12(1):3327

Du R, Wang P, Ma L et al (2020) Health-related quality of life and associated factors in patients with myocardial infarction after returning to work: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18(1):190

Doll JA (2020) Quality of life after myocardial infarction: more PROgress needed. Heart 106(1):8–9

Penedo FJ, Fox RS, Walsh EA et al (2021) Effects of web-based cognitive behavioral stress management and health promotion interventions on neuroendocrine and inflammatory markers in men with advanced prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun 95:168–177

Walsh EA, Antoni MH, Popok PJ et al (2022) Effects of a randomized-controlled trial of cognitive behavioral stress management: psychosocial adaptation and immune status in men with early-stage prostate cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 79:128–134

Penedo FJ, Fox RS, Oswald LB et al (2020) Technology-based psychosocial intervention to improve quality of life and reduce symptom burden in men with advanced prostate ancer: results from a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Med 27(5):490–505

Berger S, Schad T, von Wyl V et al (2008) Effects of cognitive behavioral stress management on HIV-1 RNA, CD4 cell counts and psychosocial parameters of HIV-infected persons. AIDS 22(6):767–775

Lopez C, Antoni M, Penedo F et al (2011) A pilot study of cognitive behavioral stress management effects on stress, quality of life, and symptoms in persons with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res 70(4):328–334

Chen J, Qian L, Chen C, Wang X (2022) The characteristics of fear of recurrence and the effect of cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention in patients after radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022:6916302

Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D et al (2021) 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 144(22):e368–e454

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS et al (2012) Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 60(16):1581–1598

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Sun X, Liu H, Jiao L et al (2017) Reliability and validity of hospital anxiety and depression scale. Chin J Chinese (Electr Ed) 11(2):198–201

Konig HH, Born A, Gunther O et al (2010) Validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D in assessing and valuing health status in patients with anxiety disorders. Health Qual Life Outcomes 8:47

Gao F, Ng GY, Cheung YB et al (2009) The Singaporean English and Chinese versions of the EQ-5D achieved measurement equivalence in cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol 62(2):206–213

Greenwood JP, Ripley DP, Berry C et al (2016) Effect of care guided by cardiovascular magnetic resonance, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, or NICE guidelines on subsequent unnecessary angiography rates: the CE-MARC 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 316(10):1051–1060

Riordan P, Davis M (2021) Anxiety and psychological management of heart disease and heart surgery. Handb Clin Neurol 177:393–408

Pogosova N, Boytsov S, De Bacquer D et al (2021) Factors associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2775 patients with arterial hypertension and coronary heart disease: results from the COMETA multicenter study. Glob Heart 16(1):73

Lv J, Zhang X, Ou S et al (2016) Influence of cognitive behavioral therapy on mood and quality of life after stent implantation in young and middle-aged patients with coronary heart disease. Int Heart J 57(2):167–172

Chauvet-Gelinier JC, Bonin B (2017) Stress, anxiety and depression in heart disease patients: a major challenge for cardiac rehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 60(1):6–12

Hamdani SU, Zill EH, Zafar SW et al (2022) Effectiveness of relaxation techniques ‘as an active ingredient of psychological interventions’ to reduce distress, anxiety and depression in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst 16(1):31

Li D, Yao Y, Chen J, Xiong G (2022) The effect of music therapy on the anxiety, depression and sleep quality in intensive care unit patients: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 101(8):e28846

Greenway SC (2021) Quality of life in adults with congenital heart disease: function over form. Can J Cardiol 37(2):186–187

Peng Y, Fang J, Huang W, Qin S (2019) Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for heart failure. Int Heart J 60(3):665–670

Talebi Amri M, Bahraminasab M, Samkhaniyan E et al (2015) Effectiveness of behavioral-cognitive group therapy on improvement of quality of life of patients with coronary heart disease. J Med Life 8(Spec Iss 4):301–306

Westas M, Lundgren J, Andersson G et al (2022) Effects of Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy adapted for patients with cardiovascular disease and depression: a long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial at 6 and 12 months posttreatment. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 21(6):559–567

Nso N, Emmanuel K, Nassar M et al (2023) Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy in heart failure patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiol Rev 31(3):139–148

Agland S, Lydon A, Shaw S et al (2018) Can a stress management programme reduce stress and improve quality of life in people diagnosed with multiple sclerosis? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 4(4):2055217318813179

Sundquist J, Palmer K, Johansson LM, Sundquist K (2017) The effect of mindfulness group therapy on a broad range of psychiatric symptoms: a randomised controlled trial in primary health care. Eur Psychiatry 43:19–27

Monticone M, Simone Vullo S, Lecca LI et al (2022) Effectiveness of multimodal exercises integrated with cognitive-behavioral therapy in working patients with chronic neck pain: protocol of a randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Trials 23(1):425

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, B., Wen, J., You, D. et al. Implication of cognitive-behavioral stress management on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in acute myocardial infarction patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Ir J Med Sci 193, 101–109 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-023-03422-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-023-03422-6