Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic saw the migration of many physiotherapy-led group exercise programmes towards online platforms. This online survey aimed to ascertain the patients’ views of online group exercise programmes (OGEP), including their satisfaction with various aspects of these programmes, the advantages and disadvantages and usefulness beyond the pandemic.

Methods

A mixed-methods design was utilised with a cross-sectional national online survey of patients who had previously attended a physiotherapy-led OGEP in Ireland. The survey collected both qualitative and quantitative data. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the ordinal and continuous data and conventional content analysis was used to analyse the free-text responses.

Results

In total, 94 patients completed the surveys. Fifty percent of patients questioned would prefer in-person classes. Despite only a quarter of patient respondents preferring online classes going forward, satisfaction with the OGEPs was high with nearly 95% of respondents somewhat or extremely satisfied. Decreased travel and convenience were cited as the main benefits of OGEPs. Decreased social interaction and decreased direct observation by the physiotherapist were the main disadvantages cited.

Conclusion

Patients expressed high satisfaction rates overall with online classes, but would value more opportunities for social interaction. Although 50% of respondents would choose in-person classes in the future, offering both online and in-person classes beyond the pandemic may help to suit the needs of all patients and improve attendance and adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Group-based exercise classes have been long used by physiotherapists worldwide in the successful rehabilitation of a wide range of conditions. Cochrane reviews have shown the success of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation [1], circuit classes for post stroke patients [2], exercise programmes to prevent falls in community dwelling older adults [3] and pulmonary rehabilitation programmes [4] to name a few. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, saw the shut-down of face-to-face exercise programmes for periods during the course of the pandemic and the rapid shift to online and home-based rehabilitative exercise programmes. An initial Cochrane review found that pulmonary rehabilitation classes delivered via telehealth may produce outcomes similar to traditional centre-based programmes [5] but with a note of caution added regarding the low number of trials, various methods of telerehabilitation employed and relatively few participants. Similarly, for stroke patients, telerehabilitation has low or moderate level evidence that it is at least as effective as in-person rehabilitation [6].

Now, as we weave our way back to post pandemic normality, as clinicians, we need to ask ourselves, do we continue with online group exercise programmes (OGEPs), in-person exercise programmes or perhaps offer both? One important factor to consider when answering this question is to ask the patients themselves as to their preference, especially those that have experienced both modes of delivery. Patient and public involvement in research is now widely recommended [7, 8]. The patients and the public have been described as “powerful sensors for shaping and powering healthcare research” [9]. Specifically for OGEPs, the patients’ perceptions play a critical role as satisfaction influences patients’ intention to adopt and partake in the programmes [10].

Various studies in a systematic review on telerehabilitation have determined that patients generally experience fewer barriers related to online rehabilitation than health providers [10]. One study examined and isolated patient feedback on a wide variety of physiotherapy-led OGEPs [11]. In this study, 19% of the 341 patient respondents reported attending OGEPs and just over half of these (56%) reported that a variety of OGEPs were of the same or superior quality compared to face-to-face classes. Studies that have investigated participant satisfaction with OGEPs can largely by broken down by population and include studies with healthy participants, studies with clinical populations and studies with older participants.

Studies that have investigated perceptions of OGEPs in healthy participants reported many positive aspects of these classes including greater time flexibility and convenience but also reported that participants missed the interaction with other exercisers and the individual support of the instructor [12, 13]. Studies have also found that healthy older adults report good levels of satisfaction with and enjoyment of OGEPs, with ranges of 77 to 100% of participants reporting they were satisfied or very satisfied with the programmes [14,15,16]. Some technological difficulties were reported as occurring occasionally in these studies, including unstable internet connections and inability to turn on cameras but overall, when questioned, video and audio quality were rated as very high [14].

Various studies have examined patient satisfaction with online group exercise programmes for specific clinical conditions including spinal cord injury [17], multiple sclerosis [18], Parkinson’s disease [19], pregnancy [20] and most notably in cardiac rehabilitation programmes [21, 22] and pulmonary rehabilitation programmes [23,24,25,26]. One of these studies compared satisfaction with OGEPs compared to in-person programmes and found no difference [23]. Convenience and flexibility were regularly cited as advantages to OGEPs and improved accessibility was regularly cited as an important advantage particularly in the neurological populations [17, 18].

In this research, we aimed to specifically collect data regarding patient perceptions of physiotherapy-led OGEPs in Ireland. The objectives of these surveys were:

-

1.

To ascertain patient perspectives on physiotherapy-led OGEPs.

-

2.

To ascertain any factors which patients identified as contributing to the overall success or failure of an OGEP.

-

3.

To find out what percentage of patients would recommend physiotherapy-led OGEPs, and advice for these programmes in the future.

This paper has been written and constructed in line with the SRQR guidelines on reporting of qualitative research [27].

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional national survey was designed after consultation with physiotherapists and based on research conducted to date in this field [11, 28]. The survey was pilot tested with 3 sample patients known to the researcher who fitted the inclusion criteria below and some minor alterations made to wordings and layout after their suggestions. A mixed-methods convergent parallel design was employed [29] with a pragmatist approach. Both qualitative and quantitative data collected through open-ended questions and Likert scale responses. This design was utilised to give a complete understanding of the research topic as well as divergent and convergent findings within the qualitative and quantitative data. The identity of the respondents remained anonymous throughout. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Sligo University Hospital Ethics Committee. The principal investigator was an experienced chartered physiotherapist with no previous experience of conducting online exercise classes and so little presuppositions regarding this particular field.

Recruitment

Prior to the patient study going live, we firstly conducted a survey with physiotherapists exploring their own experiences of conducting OGEPs. Physiotherapists who had completed the survey were asked to disseminate the patient survey amongst their eligible patients on behalf of the researching team. Patient participants were also recruited through a social media campaign via whatsapp and twitter. Patient advocacy groups were also contacted to disseminate the survey to their members. These groups included MS Ireland, the Irish Heart Foundation, Croí, COPD Support Ireland, Chronic Pain Ireland and Parkinson’s Association of Ireland. Participants were invited to complete the patient survey if they had attended a physiotherapy-led OGEP in the past.

The survey

The survey was conducted using the Qualtrics software online. The survey was available online between May and July 2022. Patients had to provide informed consent prior to commencement of the survey. A mixture of open and closed ended questions were utilised with free text response options given frequently together with 5-point Likert scale responses. The survey ascertained demographic details, clinical condition, technological confidence, satisfaction with many elements of the class including privacy, communication, video quality, barriers and facilitators to online group exercising and preferences for the future. Patients were given a “free text” response opportunity to explain why they selected their preferences for attending exercise classes into the future as well as expanding on pre-defined advantages and disadvantages of online exercise classes.

Data analysis

The Qualtrics software generated password protected reports which allowed for in-depth analysis. A convergent parallel design was employed in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research question through comparison of quantitative and qualitative data. Ordinal and continuous data were summarised through the use of descriptive statistics. Free-text responses were analysed using conventional content analysis. Key thoughts and ideas that were conveyed by exact words in the text were coded [30]. Categories were not pre-defined and instead determined by the data [30]. Free text responses were entered verbatim into password protected excel spreadsheets. Coding was then completed after researcher immersion in the data. Similar codes were grouped to form categories and from these, themes were identified. This process was verified by a second investigator (KM). Quantitative and qualitative data were separately analysed and then merged to allow for integration during this mixed-methods approach [31].

Results

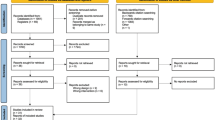

In total, 94 patients completed the survey. It is unknown how many of the 81 physiotherapists who participated in the physiotherapist’s survey actually passed the link onto their relevant patients for them to complete survey. Likewise, it is unknown how many patient advocacy groups disseminated the survey to their members. Therefore, the sample size and response rate for the patient survey are unknown.

Demographic details

Patient characteristics can be seen in Table 1. The majority of the 94 respondents were female (93%, n = 87), under 40 years old (61%, n = 57) and attended ante-natal or post-natal exercise classes (66%, n = 62). Half of the respondents (n = 40) lived in a city or town. Other classes that respondents attended included pilates (15% n = 14), classes for those with Parkinson’s disease (8%, n = 7) and general exercise (5% n = 5). Over 80% of respondents reported being moderately or extremely confident with technology (n = 77).

Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction with online classes can be seen in Fig. 1. Nearly 95% (n = 89) of respondents were either somewhat or extremely satisfied with their OGEPs.

Quality of online exercise classes

Respondents were asked questions regarding the specificities of their OGEP including sound and vision quality. The responses to these questions can be seen in Table 2. Over 86% of patients reported both the video and sound quality as somewhat or extremely good. Technological difficulties with logging in were extremely low (1%). Overall satisfaction with online security and privacy was high (87%) and so too was satisfaction with safety during exercises (90%). Comfort with communicating during the OGEP was rated lower than other aspects of the programme with nearly 14% stating that they felt somewhat uncomfortable communicating during the class.

Patient preference for future classes

Half of respondents stated that they would prefer in-person classes in the future while a quarter of respondents would prefer an OGEP. When results were subdivided by age group, those aged 60 years or older were more likely to select an OGEP as their preference for future participation with 40% of those surveyed over 60 selecting this response, compared to 22% of those under 60.

Patients were then asked to elaborate on their reasons for selecting their preference of type of exercise class with a free text response. Their responses for this question were analysed together with three other free text response opportunities related to advantages, disadvantages and generic further commentary. Altogether, there were 152 free text responses analysed. Codes, categories and themes that emerged from conventional content analysis of this data can be seen in Appendix 1. Seven themes were identified altogether.

Theme 1: OGEPs were more convenient (n = 66)

The theme with the largest number of coded mentions was the convenience of OGEPs with 66 mentions overall in the category of physical advantages of OGEPs. The word “convenience” or similar appeared 19 times in the free text responses. The code “decreased travel time” was conveyed 18 times. The coded idea of the convenience of being able to fit these classes around commitments to childcare and work appeared 14 times. One respondent commented; “The convenience of just going to next room for a live class with trusted professionals”. Another respondent commented on the convenience of decreased travel; “As I live some distance from the nearest town and find driving tiring I found the classes very convenient”.

Theme 2: enjoyment of the pacing, content and instruction quality of the OGEP (n = 46)

When given the opportunity to make generic comments, 18 mentions of enjoyment of the OGEP were noted, with words such as “brilliant” and “fantastic” used and 17 mentions of the good quality teaching and good instructors. One respondent commented; “The instructors personality made it fun and they came across very well online” and another said; “The classes were run really well. I had done other online exercise classes not run by a physio and the physio-led ones were far better and very similar to taking part in person which I had previously done”.

Theme 3: decreased social interaction/interpersonal connection (n = 42)

The next largest theme to emerge was the idea that patients missed the social interaction with others when exercising online. Coded ideas which led to the formation of this theme included “missed social interaction with other participants” (n = 41) and “poorer communication” (n = 1). Many respondents commented on how important this aspect of a face-to-face exercise class is to them; “You didn’t have the sense of community or chats” and “As a new mom to be at the time, I would have loved the chance to meet in person other women in the same boat”.

Theme 4: decreased in-person supervision reduced the perceived quality of the OGEP (n = 29)

Another theme falling into the “interactive disadvantages of OGEPs” category was the idea that reduced direct and in-person supervision reduced the quality of the instruction. Coded ideas which led to the formation of this theme included; “Less interaction with instructor” and “Exercises not individualised”. Many felt that this lack of close physical interaction with the instructor meant that the instructor could not correct their form and technique precisely and could not individualise the exercises and feedback. This led many participants to worry that they were not doing the exercises correctly. One respondent stated; “Physio wasn’t able to observe me and assess my needs and how accurately I was performing exercises”. Another commented on the importance of direct observation; “While online has many benefits, I would prefer to be directly observed by the physio and get feedback on how I am performing the exercises”.

Theme 5: some patients found it difficult to stay motivated and focussed during the OGEP (n = 17)

Some respondents had concerns that they were less motivated and less focussed with OGEPs. This idea had 14 mentions. One respondent commented; “I missed the in-person group motivation for class to push myself to do more reps of exercise etc.” while another reported that it was easy to get distracted or be late while attending the class at home and that they might be more likely to do “a task/chore on the way”. Others felt that they were more likely to commit to an in-person class (n = 2).

Theme 6: the set-up of OGEPs at home did not work well for some patients (n = 17)

Physical disadvantages to exercising at home were mentioned 6 times, with reports of the home set up being too small or “too cramped” for exercising. Also, although many commented, as mentioned above, about the convenience of exercising at home, especially with small children about, others had contrasting ideas and conveyed the importance of “getting out of the house” to exercise (n = 6); “(In-person classes are) a nice opportunity to get out of the house, particularly when busy with working and small children at home”. Technological difficulties were cited 4 times. All of these codes were placed in the category, physical disadvantages to OGEPs.

Theme 7: a hybrid approach is the preferred option for many (n = 15)

Many patients recognised that having the option to attend either online or in-person classes is the best way forward (n = 13) with some recognising that different classes suit different needs (n = 2). One mother recognised that different types of classes suit different people along the life span; “As a mother now, I’m very limited time wise. When I was younger going to classes would have suited me better, now the online classes are a godsend”.

Quantitative assessment of advantages and disadvantages of OGEPs

The ideas generated in these free text responses above were echoed when patients were formally asked to identify from a list of options, what they felt were the advantages and disadvantages of OGEPs. Respondents were allowed to make multiple choices.

In terms of advantages, less travel, less risk of COVID-19 infection and less time consuming came out as the most selected answers with 84% (n = 79), 77% (n = 72) and 64% (n = 60) of respondents choosing to select these answers. Most of the top-rated advantages linked in with the largest theme, theme 1 above, “convenience”. Full results of the advantages selected by respondents can be seen in Table 3.

On top of the list of selected disadvantages for OGEPs were a lack of social interaction and an inability to communicate with the class instructor with 71% (n = 67) and 25% (n = 23) selecting these answers and linking well with themes 3 and 4 above. Full results of the disadvantages selected by respondents can be seen in Table 4.

The only divergent finding, where qualitative and quantitative data did not match, was in relation to safety from COVID-19 infection. When specifically questioned as to whether this was an important advantage of attending OGEPs, 77% of respondents agreed that it was. However, across all 152 free text responses prior to this question, there were only 7 mentions of feeling safe from COVID-19 infection during online exercising.

Discussion

This survey is the first of its kind, known to us, to specifically question patients regarding their experience with and perceptions of physiotherapy-led OGEPs in Ireland. Our main findings indicated that satisfaction with OGEPs was high with nearly 95% of respondents somewhat or extremely satisfied. Decreased travel, convenience, less time consumption and decreased risk of COVID-19 infection were cited as the main benefits of OGEPs by patients. Decreased social interaction, decreased communication and interaction with the instructor, difficulties with home set up and difficulties remaining motivated were the main disadvantages. When questioned about preference for future exercising, 50% of patients questioned would prefer in-person classes while 25% would opt for OGEPs in the future.

Satisfaction and acceptability

Our high satisfaction rates were similar to other studies investigating clinical populations and healthy older adults who reported good levels of satisfaction with OGEPs, with 77 to 100% of participants reporting they were satisfied or very satisfied with the programmes [14,15,16, 32, 33]. Our findings of high overall satisfaction with the OGEPs are important as satisfaction is an influential determinant of motivation to stick with an exercise programme [34]. Patient satisfaction is particularly important in online interventions as the patients are the only source of information that can report on the intervention and if it met their expectations of care [35]. Although patient satisfaction may not be a measure of outcome, it is a measure of the quality of the intervention [35].

When considering the results of our study, it must be noted that the majority of our participants were under 40 (61%) and had attended either ante or post-natal exercise classes and this fundamentally affects all of our findings and dilutes the generalisability of our results. However, we can draw comparisons between our study and similar themes that emerged from a study by Silva-Jose et al. (2022), who conducted semi-structure interviews with 24 pregnant women regarding their experience with OGEPs [22]. Like our study, the general preference in this study was for in-person classes in the future but the participants recognised the many benefits of OGEPs, including and like our cohort, safety and stability exercising in their home environment and the elimination of the time barrier. A systematic review found that pregnant women spend more than 50% of their time sedentary and increased sedentary time was associated with higher levels of C reactive protein, LDL cholesterol and a larger newborn abdominal circumference [36]. Barriers to exercise participation in pregnancy include limited knowledge and access to information on safe exercise in pregnancy [37] as well as fatigue, lack of time and pregnancy discomforts [38]. Our findings, echoing previous results [22, 39], provide some initial evidence that online platforms may be a feasible and acceptable way to deliver antenatal exercise programmes. Furthermore, considering a lack of time is oft-cited as a barrier to exercise in pregnancy [38], adherence to an OGEP may be positively influenced by the elimination of this barrier. Also, in late pregnancy, a feeling of “nesting” may compel women to stay close to home [22], and so exercising from home may provide more security. One of our respondents reported: “As it was online it allowed me to attend right up to 38 weeks of pregnancy even after driving had become quite difficult”. In this way, again, moving online may influence adherence but these theories have yet to be proven.

Quality of the online exercise programmes

With regard to the finer details of the OGEP, our study found that approximately half of respondents reported the video and sound quality was “extremely good” and approximately 40% of the respondents classified them as “somewhat good”. The successful delivery of an OGEP is dependent on good telehealth infrastructure including internet speeds and access to devices. Clinicians have voiced concerns about disadvantaged patients having poorer telehealth infrastructure [40]. There is a difference between watching an exercise being demonstrated on a small mobile phone screen compared with a large computer screen and also internet reliability effects the enjoyment of and ability to successfully participate with the synchronous delivery of an OGEP [41]. Ultimately, there is a potential risk that rural and/or financially impoverished users may have a lesser quality experience of OGEPs due to poor telehealth infrastructure [42].

As well as those with reduced access to devices and reliable internet, those with lower technological confidence may not be able to interact with online platforms as well as those with more confidence. For older adults, previous studies have shown various feelings towards and readiness for telehealth interventions. In a survey of over 1000 older adults (aged 65 or over) by Chu et al. (2022), 37% were not “video-enabled”, meaning they either needed technical assistance or did not have access to an electronic device [43]. However, in a poll of over 2000 nationally representative US adults aged 50–80 years, those aged 65 or older were more likely than younger individuals to be interested in a first-time telehealth visit [44]. These latter results noted a “digital divide” rather than an age divide affecting interest in telehealth. In our study, those aged 60 years or older (n = 20) were actually more likely to select OGEPs as their preference for future participation with 40% (n = 8) of those surveyed over 60 selecting this response, compared to 22% (n = 16) of those surveyed who were under 60. We were not able to effectively carry out a sub-analysis of only those who were not confident with technology as only one participant rated their confidence with technology as “not at all confident”. In order to capture this data, phone interviews or focus groups may be preferrable to online surveys which may deter those who are not confident with technology from responding.

Possible solutions to overcome these barriers of poor telehealth infrastructure and poor technological confidence have been suggested. One of our respondents commented on the usefulness of “Digital Hubs in rural locations that can support older people wanting to learn”. Initiatives which aim to enhance digital skills or loan devices such as tablets with sim cards for internet access to patients should be supported by our health service to reduce this digital divide. In-person demonstration of technology including use of the device, accessing the internet, logging into classes may also be useful to increase confidence [45]. If necessary, a patient might require a caregiver at home to provide technological support and improve the patient’s overall experience.

Safety

In our study, nearly 60% of participants were extremely satisfied with their own safety and just over 30% were somewhat satisfied. As physiotherapists, the safety of our patients is a paramount concern and we would aim that our patients would always feel extremely safe exercising with us. However, it appears that for some, not being directly observed by the instructor renders them to be apprehensive. Reduced quality of interaction with the physiotherapist and reduced observation and feedback from the physiotherapist during the class was a commonly cited disadvantage of OGEPs in our study and is a similar finding in previous studies also [11, 13]. Many patients worried about the correctness of their technique during exercising without direct physiotherapist observation.

In order to enhance patient safety, physiotherapists are encouraged to adhere to an international core capability framework for physiotherapists which has been developed to enable delivery of quality care via videoconferencing. Physiotherapists are encouraged to take safety precautions when engaging with telehealth including; screening patients’ suitability for telehealth, having procedures in place in case of emergency, identifying safety hazards remotely and enlisting the assistance of a patient care giver when required [46]. These strategies have been applied successfully in some studies, with 100% of the post stroke patients in the study by Galloway et al. (2019) agreeing that they felt safe during the online exercise sessions as a result [47]. The specific strategies employed by these authors were in-person demonstration of exercises and use of telehealth, an assisting caregiver at home during exercise sessions, physiological monitoring and a risk assessment of the exercise space.

As well as these recommended strategies to enhance safety, some patients in our study had their own solution for the issues of safety and technique concerns, citing the benefit of a hybrid approach into the future; “I would like a mix. Online most of the time but every month have one in person class”. This approach may help patients to feel safe and reassured that they have the correct technique and that they are progressing well. Another patient stated that OGEPs might be better as a follow up set of classes rather than a first experience of an exercise class; “When I am comfortable with the exercises doing it from home is a lot more convenient”. This would also give the physiotherapist time to build rapport with the patient and become familiar with their movement patterns and technique errors and it allows the patient to build trust in the physiotherapist, which may make the transition to online, for a follow up class, smoother. This idea of having an existing relationship with a trusted and familiar clinician prior to the telehealth experience is one that has been cited as being beneficial in previous literature [48] and was echoed by participants in our own study; “(I) Think it is an advantage knowing the instructor through in person classes before going online”. Patients in previous studies also highlighted the importance of constant, individualised feedback during online sessions [18, 22].

Convenience

Convenience appeared to be the overwhelming advantage of OGEPs according to our patient respondents with 60% agreeing that they are more convenient than in-person classes and 84% stating that not having to travel to classes was an advantage. Convenience is also a key benefit most frequently cited by patients in various settings in previous studies [11, 12, 48]. This reported convenience may be a key factor in increasing adherence to exercise programmes with patients perhaps more likely to attend if there is minimal disruption to their daily routine and reduced cost and burden of transport and parking issues. Telehealth has been considered by previous authors to be a potential way to improve access to treatment in rural and underserved areas [49, 50] and certainly the convenience of telehealth in terms of reduced travel was felt more by patients in our survey who lived in more rural locations, with 41% of these patients specifically stating a preference for OGEPs into the future compared to only 25% of all respondents.

Social interaction

Although a lack of social interaction between participants was cited as a common disadvantage of OGEPs in our study, it was apparent that some physiotherapists had made an effort to improve this issue for participants. Two patients reported that their physiotherapists had created a class “whatsapp” group to enhance interaction and communication between participants. One patient respondent reported; “I found there was great support from the group as a whats app group was created and thus allowed everyone from the class to ask questions which I found very helpful and the instructor was very informative”. Another patient reported how her physiotherapist facilitated a small group discussion at the end of the class which helped increase interaction. These added extras, if adopted, may help to enhance future OGEPs. In one study examining how technology limited or facilitated online exercisers’ experiences of social interactions in an OGEP, the authors found that exercisers who had the opportunity to have pre and post exercise social interactions with others valued it even more than the in-person classes and it motivated them to sustain their participation [51]. However, the authors did recognise that unlike in in-person classes, the responsibility for facilitating social interactions lay solely with the instructor and it was recommended that instructors allocate time for these interactions and facilitate the conversations. Other studies have recommended organising online forums for participants to interact and support one another with a moderator posing topics of conversations or facilitating discussions, especially in chronic disease [52].

Looking to the future

Despite our high satisfaction rates, our study showed relatively low figures for preferences for continuing with OGEPs into the future with only 25% choosing this option. The figure of 25% is less than in previously reported literature in this field. In an Australian study by Bennell et al. (2021) [11], 68% of the 77 respondents who underwent OGEPs reported that they were likely or extremely likely to attend group classes via videoconferencing in the future. Also, 79% of a cohort of 20 people with COPD who underwent an OGEP [32] reported that they would opt for OGEPs in the future. The difference between our figures and the previously reported figures may simply be due to the wording of the question. We asked our participants “What would be your preference for attending exercise classes in the future?” and gave patients the options of “online”, “in-person”, “no preference” or “unsure”, whereas the aforementioned studies only asked their patients how likely they would be to continue with OGEPs in the future. Our results do, however, align with some studies that did give patients an option when questioning about preference. In a survey regarding patient perceptions about an oncology OGEP, 57 participants who had previously completed both in-person classes and OGEPs were asked to give their preferences for exercise programmes in the future and 58% preferred in-person programmes while 32% preferred online [53].

When looking to the future, the high satisfaction rate with and various advantages to OGEPs reported by our respondents supports the continued role out of online, live, physiotherapy-led group exercise programmes. However, “one size does not fit all” [48] and online exercise classes should be offered in conjunction with and perhaps even, simultaneously to, in-person classes in order to maximise access, improve safety, improve exercise technique and ultimately, provide for the needs of all types of patients. The classes should have a deliberate design and should consider the opinions of the patients as outlined in this study. These online classes should be tailored to specific clinical groups with individualised assessment [45, 46]. Physiotherapists should consider ways to improve social interaction including facilitating group discussions, moderating chat forums and provide individualised feedback which have been shown in this study and other small studies [26, 51] to be valuable to participants and may improve patient motivation.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study was our inability to capture a larger and more varied group of patient respondents. We were reliant on physiotherapist respondents to share the survey amongst their previous participants and a large number of physiotherapists who had conducted ante-post natal classes chose to share the study with their participants. We only captured data from a very small cohort of patients who attended pulmonary rehabilitation, cardiac rehabilitation or falls or balance classes (n = 3). This affects the generalisability of our results to a wider population, particularly to those with chronic disease or disabilities or to older persons. Our results may also not be generalisable to other countries with different practices and regimes.

Conclusion

This study found that patient satisfaction with the OGEP they attended was high; however, only a quarter of patients reported they would prefer to attend an OGEP in the future with half of the patients reporting that their future preference would be in-person classes. Convenience was reported as the main advantage of OGEPs and reduced social interaction and interaction with the instructor were considered the main disadvantages. Future studies should aim to conduct focus groups and interviews with a wider cohort of patient participants involved in a variety of OGEP to gain the perspectives of those with varying levels of confidence in technology.

Recommendations for clinical practice

-

1.

Physiotherapists should consider providing online exercise classes for specific clinical groups as an adjunct to or simultaneous to in-person class offerings to maximise patient access and adherence.

-

2.

Patients value dedicated opportunities during these online classes for social interactions and chats.

-

3.

Patients value individualised feedback and tailored exercises during online classes.

-

4.

Patients living in rural locations and those partaking in a follow-up class or non-beginner exercisers may prefer an online exercise class more than others.

-

5.

Physiotherapists should recognise that there exists a “digital divide” amongst patients and should seek out schemes that aim to improve access to devices and the internet as well as support those who lack technological confidence.

Data availability

Raw data supporting the findings of this study were generated at ATU Sligo and are available from the corresponding author [EC] on request.

References

Long L, Mordi IR, Bridges C et al (2019) Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(1):CD003331. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003331.pub5. PMID: 30695817; PMCID: PMC6492482

English C, Hillier SL, Lynch EA (2017) Circuit class therapy for improving mobility after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6(6):CD007513. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007513.pub3. PMID: 28573757; PMCID: PMC6481475

Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK et al (2019) Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(1):CD012424. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2. PMID: 30703272; PMCID: PMC6360922

McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D et al (2015) Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Sys Rev (2):CD003793. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3

Cox NS, Dal Corso S, Hansen H et al (2021) Telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease. Cochrane Database Sys Rev (1):CD013040. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013040.pub2

Laver KE, Adey‐Wakeling Z, Crotty M et al (2020) Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Sys Rev (1):CD010255. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010255.pub3

Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I et al (2017) GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ 358:j3453. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3453. PMID: 28768629; PMCID: PMC5539518

Brand S, Bramley L, Dring E et al (2020) Using patient and public involvement to identify priorities for research in long-term conditions management. Br J Nurs 29(11):612–617. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2020.29.11.612. PMID: 32516042

Price A, Clarke M, Staniszewska S et al (2022) Patient and public involvement in research: a journey to co-production. Patient Educ Couns 105(4):1041–1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.07.021. Epub 2021 Jul 19. PMID:34334264

Niknejad N, Ismail W, Bahari M, Nazari B (2021) Understanding telerehabilitation technology to evaluate stakeholders’ adoption of telerehabilitation services: a systematic literature review and directions for further research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 102(7):1390–1403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.12.014. Epub 2021 Jan 20 PMID: 33484693

Bennell KL, Lawford BJ, Metcalf B et al (2021) Physiotherapists and patients report positive experiences overall with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. J Physiother 67(3):201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2021.06.009. Epub 2021 Jun 9. PMID: 34147399; PMCID: PMC8188301

Füzéki E, Schröder J, Reer R et al (2022) Going online?-can online exercise classes during COVID-19-related lockdowns replace in-person offers? Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4):1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19041942. PMID:35206129;PMCID:PMC8872076

Brinsley J, Smout M, Davison K (2021) Satisfaction with online versus in-person yoga during COVID-19. J Altern Complement Med 27(10):893–896. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2021.0062. Epub 2021 Aug 2. PMID: 34339262

Schwartz H, Har-Nir I, Wenhoda T, Halperin I (2021) Staying physically active during the COVID-19 quarantine: exploring the feasibility of live, online, group training sessions among older adults. Transl Behav Med 11(2):314–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibaa141. PMID:33447852;PMCID:PMC7928678

Granet J, Peyrusqué E, Ruiz F et al (2023) Web-based physical activity interventions are feasible and beneficial solutions to prevent physical and mental health declines in community-dwelling older adults during isolation periods. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 78(3):535–544. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glac127. PMID:35675174;PMCID:PMC9384240

Buckinx F, Aubertin-Leheudre M, Daoust R et al (2021) Feasibility and acceptability of remote physical exercise programs to prevent mobility loss in pre-disabled older adults during isolation periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nutr Health Aging 25(9):1106–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-021-1688-1. PMID:34725669;PMCID:PMC8505216

Mehta S, Ahrens J, Abu-Jurji Z et al (2021) Feasibility of a virtual service delivery model to support physical activity engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic for those with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 44(sup1):S256–S265. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2021.1970885. PMID:34779728;PMCID:PMC8604449

Kim Y, Mehta T, Tracy T et al (2022) A qualitative evaluation of a clinic versus home exercise rehabilitation program for adults with multiple sclerosis: the tele-exercise and multiple sclerosis (TEAMS) study. Disabil Health J 21:101437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101437. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36658077

Morris ME, Slade SC, Wittwer JE et al (2021) Online dance therapy for people with Parkinson’s disease: feasibility and impact on consumer engagement. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 35(12):1076–1087. https://doi.org/10.1177/15459683211046254. Epub 2021 Sep 29 PMID: 34587834

Silva-Jose C, Nagpal TS, Coterón J et al (2022) The ‘new normal’ includes online prenatal exercise: exploring pregnant women’s experiences during the pandemic and the role of virtual group fitness on maternal mental health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22(1):251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04587-1. PMID:35337280;PMCID:PMC8953965

Knudsen MV, Laustsen S, Petersen AK et al (2021) Experience of cardiac tele-rehabilitation: analysis of patient narratives. Disabil Rehabil 43(3):370–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1625450. Epub 2019 Jul 12 PMID: 31298957

Pastora-Bernal JM, Hernández-Fernández JJ, Estebanez-Pérez MJ et al (2021) Efficacy, feasibility, adherence, and cost effectiveness of a mHealth telerehabilitation program in low risk cardiac patients: a study protocol. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(8):4038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084038. PMID:33921310;PMCID:PMC8069438

Cerdán-de-Las-Heras J, Balbino F, Løkke A et al (2021) Effect of a new tele-rehabilitation program versus standard rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Med 11(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11010011. PMID: 35011755; PMCID: PMC8745243

Simonÿ C, Andersen IC, Bodtger U et al (2022) Raised illness mastering - a phenomenological hermeneutic study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients’ experiences while participating in a long-term telerehabilitation programme. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 17(5):594–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2020.1804630. Epub 2020 Aug 26 PMID: 32845801

Hoaas H, Andreassen HK, Lien LA et al (2016) Adherence and factors affecting satisfaction in long-term telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 25(16):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0264-9. PMID:26911326;PMCID:PMC4766676

Inskip JA, Lauscher HN, Li LC et al (2018) Patient and health care professional perspectives on using telehealth to deliver pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 15(1):71–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972317709643. Epub 2017 Jun 1. PMID: 28569116; PMCID: PMC5802656

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ et al (2014) Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 89(9):1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. PMID: 24979285

Reynolds A, Sheehy N, Awan N et al (2022) Telehealth in physiotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic, the perspective of the service users: a cross-sectional survey. Physiotherap Pract Res 1 – 8

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2018) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 5th edn. SAGE, Los Angeles

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687. PMID: 16204405

Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW (2013) Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res 48(6 Pt 2):2134–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117. Epub 2013 Oct 23. PMID: 24279835; PMCID: PMC4097839

Tsai LLY, McNamara RJ, Dennis SM et al (2016) Satisfaction and experience with a supervised home-based real-time videoconferencing telerehabilitation exercise program in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Int J Telerehabil 8(2):27–38. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2016.6213. PMID: 28775799; PMCID: PMC5536727

Hwang R, Mandrusiak A, Morris NR et al (2017) Exploring patient experiences and perspectives of a heart failure telerehabilitation program: a mixed methods approach. Heart Lung Jul-Aug 46(4):320–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.03.004. Epub 2017 Apr 17 PMID: 28427763

Allender S, Cowburn G, Foster C (2006) Understanding participation in sport and physical activity among children and adults: a review of qualitative studies. Health Educ Res 21:826–835. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl063

Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B et al (2017) Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open 7(8):e016242. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016242. PMID: 28775188; PMCID: PMC5629741

Fazzi C, Saunders DH, Linton K et al (2017) Sedentary behaviours during pregnancy: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 14(1):32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0485-z. PMID:28298219;PMCID:PMC5353895

Grenier LN, Atkinson SA, Mottola MF et al (2021) Be healthy in pregnancy: exploring factors that impact pregnant women’s nutrition and exercise behaviours. Matern Child Nutr 17(1):e13068. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13068. Epub 2020 Jul 23. PMID: 32705811; PMCID: PMC7729656

Harrison AL, Taylor NF, Shields N, Frawley HC (2018) Attitudes, barriers and enablers to physical activity in pregnant women: a systematic review. J Physiother 64(1):24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2017.11.012. Epub 2017 Dec 27 PMID: 29289592

Hillyard M, Sinclair M, Murphy M et al (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on the physical activity and sedentary behaviour levels of pregnant women with gestational diabetes. PLoS One. 16(8):e0254364. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254364. PMID: 34415931; PMCID: PMC8378749

Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Raja P et al (2020) Suddenly becoming a “Virtual Doctor”: experiences of psychiatrists transitioning to telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Serv 71(11):1143–1150. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000250. Epub 2020 Sep 16. PMID: 32933411; PMCID: PMC7606640

Khoshrounejad F, Hamednia M, Mehrjerd A et al (2021) Telehealth-based services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of features and challenges. Front Public Health 9:711762. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.711762. PMID: 34350154; PMCID: PMC8326459

Hickey D (2021) The potential scope and limits of post COVID-19 telepsychiatry in Ireland. Irish J Psychol Med 38(4):320–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2021.68

Chu JN, Kaplan C, Lee JS et al (2022) Increasing telehealth access to care for older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic at an academic medical center: video visits for elders project (VVEP). Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 48(3):173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.11.006

Kurlander JE, Kullgren JT, Adams MA et al (2021) Interest in and concerns about telehealth among adults aged 50 to 80 years. Am J Manag Care27(10):415–422. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2021.88759. PMID: 34668670

Ramage ER, Fini N, Lynch EA et al (2021) Look before you leap: interventions supervised via telehealth involving activities in weight-bearing or standing positions for people after stroke-a scoping review. Phys Ther 101(6):pzab073. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab073. PMID: 33611602; PMCID: PMC7928700

Davies L, Hinman RS, Russell T et al (2021) An international core capability framework for physiotherapists to deliver quality care via videoconferencing: a Delphi study. J Physiother 67(4):291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2021.09.001. Epub 2021 Sep 11. PMID: 34521586

Galloway M, Marsden DL, Callister R et al (2019) The feasibility of a telehealth exercise program aimed at increasing cardiorespiratory fitness for people after stroke. Int J Telerehabil 11(2):9–28. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2019.6290. PMID:35949926;PMCID:PMC9325643

Toll K, Spark L, Neo B et al (2022) Consumer preferences, experiences, and attitudes towards telehealth: qualitative evidence from Australia. PLoS One 17(8):e0273935. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273935. PMID: 36044536; PMCID: PMC9432716

Butzner M, Cuffee Y (2021) Telehealth interventions and outcomes across rural communities in the United States: narrative review. J Med Internet Res 23(8):e29575. https://doi.org/10.2196/29575. PMID: 34435965; PMCID: PMC8430850

Kolluri S, Stead TS, Mangal RK et al (2022) Telehealth in response to the rural health disparity. Health Psychol Res 10(3):37445. https://doi.org/10.52965/001c.37445. PMID: 35999970; PMCID: PMC9392842

Gui F, Tsai CH, Vajda A, Carroll JM (2022) Workout connections: investigating social interactions in online group exercise classes. Int J Hum Comput Stud 166:102870. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHCS.2022.102870

Culos-Reed SN, Wurz A, Dowd J, Capozzi L (2020) Moving online? How to effectively deliver virtual fitness. ACSMs Health Fit J 25:16–20

Duchek D (2021) Understanding in-person and online exercise oncology program delivery: participant perspectives (unpublished master’s thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

Funding

This research has been undertaken as part of a funded PhD programme thanks to ATU Sligo’s Masters Scholarship scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Sligo University Hospital Research and Ethics Committee #872. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of this committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Informed consent form can be seen in Appendix 2.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Codes, themes and categories that emerged from conventional content analysis of 152 free text responses across various opportunities for commentary during the patients’ survey. Themes presented in order of largest to smallest representation.

Appendix 2: Informed Consent

The section below will appear on the first page of the survey. The participants need to consent in order to move on to the main survey. If they do not give their consent, they are transferred to the end of the survey.

Consent Form

Study Title: Physiotherapists and patients views on online exercise classes during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Please read carefully and tick EACH box to indicate agreement:

I am aged 18 years old or over | □ |

I confirm that I have read and understood the information leaflet for the above research study and received an explanation of the nature, purpose, duration and foreseeable effects and risks of the research study and what my involvement will be | □ |

I have had time to consider whether to take part in this research study | □ |

My questions have been answered satisfactorily in the participant information document | □ |

I understand that my participation is voluntary (my choice) and that I am free to withdraw at any time before completion of the survey | □ |

If you would not like to participate, please exit the browser.

-

I agree to the above terms and consent to the participate in this study

-

I do not agree to the above terms and do not consent to participate in this study

(Once participant ticks all boxes, they can click SUBMIT which will be a button at the bottom of this page and will bring them to the survey)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cronin, E., McCallion, M. & Monaghan, K. “The best of a bad situation?” A mixed methods survey exploring patients’ perspectives on physiotherapy-led online group exercise programmes. Ir J Med Sci 192, 2595–2606 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-023-03386-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-023-03386-7