Abstract

Background

Postgraduate General Practice (GP) training is structured around a formal curriculum set out by the training body. It also includes a “hidden curriculum” of experiential workplace learning in a heterogenous learning environment [1]. There is no formal national annual survey of GP trainees and their views in Ireland.

Methods

The research aim was to evaluate what the trainee population think of their training environment, and to analyse the contributory factors. A mixed methods cross-sectional survey was distributed to all third- and fourth-year GP trainees (N = 404). The Manchester Clinical Placement Index was adapted for the study.

Results

The response rate was 30.94% (N = 125). Questions 1 to 7 provided a description of the characteristics of the study population. The remainder of the questions focused on aspects which relate to constituents of the learning environment. The responses were broadly and convincingly positive and supportive of the good work being done in GP training and by trainers in Ireland today across both qualitative and quantitative findings. One notable exception was in the area of feedback where single handed fourth year practices were found to be underperforming.

Conclusions

The current research findings were broadly positive and supportive of the good work being done in GP training and by trainers in Ireland today. Further research will be needed to validate the study instrument and to further refine some aspects of its configuration. The implementation of such a survey on a regular basis may have merit as part of the quality assurance process in GP education alongside existing feedback structures [2].

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

GP training in Ireland is provided through fourteen training schemes under the auspices of the Irish College of General Practitioners (ICGP), the national GP training body. Trainees spend four years on their training programme. The first 2 years are in hospital-based rotations working in NCHD roles and the final 2 years are spent in year-long training attachments with an individual GP trainer in a dedicated training practice. Owing to the heterogenous nature of medical practice and the varied working and business arrangements in each GP surgery, there is considerable variation in the approaches taken to training. As well as the formal curriculum and core competencies expected of trainees, which are set out by WONCA (World Organization of Family Doctors) and the ICGP, a significant part of GP education is achieved in experiential workplace learning through the master-apprentice relationship. This is often described as the “hidden curriculum” and it covers a range of implicit lessons learnt through practice and interpersonal interactions in areas such as cultural competence, achieving medical professionalism, and dealing with uncertainty [1]. There is no formal national annual trainee survey dedicated to GP trainees and their views.

In Ireland, the acceptability of the postgraduate education to each GP trainee and their perceptions of training is assessed for the most part on an individualised basis at local GP training scheme level through one-to-one meetings between each trainee and their trainer where they receive feedback and discuss their progress every 6 months. At these meetings the trainee gives an assessment of the trainer’s performance while reciprocally they received feedback on their own progress in training. Trainees’ reported feedback and perceptions are also the principal means of assessing both the quality of training delivered and trainer competency in the programme [3].

In effect, there is a link between trainees’ giving their perceptions of training and their receipt of competency accreditation. It is the authors’ concern that this may create a bias towards positive trainee feedback on the quality of the learning environment and militate against expressing negative feedback as trainees may believe that providing negative commentary may preclude them from progressing on their training scheme [3].

This research study examines the experiences of trainees in third and fourth year of post-graduate training as these years are specific to GP practice-based training. It is hoped that this survey will shed light on how GP trainers interact with their trainees by allowing trainees an anonymised protected forum to express their opinions and, in so doing reveal how GP training is conducted in Ireland at present.

Methods

Study aim and design

The aim of this study is to assess what the trainee population think of their training environment, and to analyse the factors which help to create that environment. This was carried out using a mixed methods approach which was deployed using a cross-sectional research survey.

Study population and sampling

A questionnaire was distributed to all third- and fourth-year GP trainees (N = 404). Prior approval for the study was requested from and granted by the ICGP. All trainees were included. No exclusion criteria were applied. Participants were incentivised to take part by entry into a raffle for a voucher. Typical expected response rates for this type of research, notwithstanding incentives, is 24% [4].

Study instrument

The Manchester Clinical Placement index (MCPI) was chosen as the instrument of choice for the current study [5]. The tool required adaptation as the original MCPI was validated in an undergraduate setting. This was carried out by expert panel review. The tool is henceforth termed the MCPIadapted (see Table 1).

Ethical considerations and data protection

Ethical approval was sought from and granted by the ICGP Clinical Ethics Committee and the Dundee University Ethics Committee prior to commencement.

Data analysis methods

Qualitative data was coded using Microsoft Excel Version 16.43 (Microsoft Inc, USA). done in accordance with the guidelines for thematic analysis using NVivo release 1.0 (QSR International, Australia) [6]. The descriptive statistics and statistical analysis were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Software, USA). For each multiple-choice question, responses were summarized as frequencies and proportions. Summary statistics were calculated for the total dataset and across the following strata: year of training, practice type and practice location. The final 10 questions in the questionnaire (Supervision, Reception and Induction, People, Entrustment, Monitoring, Modelling, Dialogue, Feedback, Facilities and Structure of the post) were part of a 10-item measurement index. For the original questionnaire the authors’ subdivided items into the terms “training” and “learning environment” and was estimated according to the calculations:

This subdivision is less applicable to postgraduate training and such a subdivision was not suggested in the adaptations made by the expert panel. The scoring for the current study was subsequently clarified through communication with the original study author which supported this adapted calculation [7]. The development of a GP trainee is the product of both the training they receive and the environment within which they receive it, hence the index was calculated as a score of all answers from the current 10-item questionnaire in this study [8]. The MCPIadapted percentage score for each respondent was therefore calculated as follows:

The MCPIadapted is an overall score of each respondent and represents their satisfaction with the training environment. Therefore it represents a percentile and it exists to aide direct side by side comparison of each answer and in future it will provide a means of trending overall annual scores.

Results

The current study’s results are presented in four sections. First an overview of the descriptive quantitative results is presented. Second, the quantitative analysis is subdivided into figures by year of training, practice type, and practice location. Third, the MCPIadapted index score distributions are presented. Finally, the qualitative figures and comments are shown. These are categorised by respondent attributes and overarching themes noted across the responses are described.

Quantitative findings

There was a response rate of 30.94% (N = 125). Questions 1 to 7 outlined demographic data and provided a description of the characteristics of the study population. 35.2% of the population were male and 64.8% were female. There was a broad range in the age of respondents:

-

15.2% aged 25–29 years

-

46.4% aged 30–34 years

-

32% aged 35–39 years

-

4% aged 40–44

-

2.4% aged 44 years and over

43.2% were from year 3 and 56.8% were from year 4. 74.4% were working in a group practice and 25.6% were based in single-handed practices. 34.3% worked in a practice in a rural setting; 41.6% worked in an urban setting; 24% worked in a geographical location where the patient population was spread across both setting types. There was a broad time gap between graduation from medical school and enrolment in GP with a range of year of graduation from medical school from 2003 to 2018. 66.4% were not enrolled on a previous medical training scheme.

Quantitative data for each individual question was assessed on a 7-point Likert scale. For questions 8 to 26 all responses were weight towards positive responses (strongly agree, agree or somewhat agree). The full data summary table is available in the appendices. An example of the data is presented for Question 8 here (see Table 2).

Subdivided quantitative findings

The quantitative findings which were given in a broad overview above were further analysed by subdividing the findings by year of training, practice location, and practice type.

Responses divided by year of training

The quantitative findings for Year of Training (Q3) were subdivided by each question and were plotted on bar charts. The figures in are presented as percentages of the row total and are available in the appendix. The figures were closely matched for each year. An example of the responses is outline for in the area of Supervision below (see Figs. 1).

Responses by practice type

Similarly, the quantitative findings for practice type were subdivided by each question. Again, these were closely matched for each type of practice. An example is depicted below for Supervision where due the higher number of group practices surveyed the percentages appear higher for group practices, but remain proportional overall across both categories (see Fig. 2).

Responses divided by Practice Location

The qualitative findings for practice location (Q5) were also subdivided according to each question. The figures which are available in the appendix are presented as percentages of the row total. An example for Supervision is shown below. Again the results are closely matched (Fig. 3).

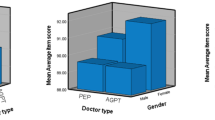

Distribution of MCPIadapted scores

The MCPIadapted can be scored based on the response format which was a 7-point Likert scale (disagree-agree scores from 0–6). Higher scores therefore represented more positive responses. These results were again subdivided by year of training, practice type, and practice location. When depicted graphically, the results reflect the distribution of responses mentioned above and are closely matched as shown below. The absolute figures are described in the appendix (see Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7).

Qualitative findings

Individual qualitative answers were coded to give an overview of the nature of the responses. Broadly, the codes depicted positive and negative response as outlined in the study instrument. These are displayed as bar charts depicting the number of positive and negative codes for each question. Selected examples of quotes which best represented the broader set of responses are displayed to give a greater sense of the nature of the qualitative data. The data was coded and further analysed for common themes where these appear, and this is presented below. In cases where codes overlapped between positive/negative answers and an overarching theme they were coded twice so as not to detract from either count. Cases in each category (year, practice location) are expressed in parentheses.

Responses to individual questions

Respondents were asked their opinions on a variety of areas of training. They were given the prompts “Strengths of ____ were … Weaknesses or ways ____ could be improved …”. For reference, the supplied definition for the term which describes each area is included below. A summary bar chart of each question outlines how the distribution of responses were weighted. Selected examples of quotes from the population are also presented for each question.

Question 9 Supervision

There is supervision if one or more senior doctors take responsibility for your education and training (see Fig. 8 and Table 3).

Question 11. Reception and induction

An appropriate reception and induction is a welcome that includes an explanation of how the post can contribute to your learning (see Fig. 9 and Table 4).

Question 13. People

The support to your learning from people (like doctors, secretaries, receptionists, nurses, and others) you worked with in this post (see Fig. 10 and Table 5).

Question 15. Entrustment

Appropriate entrustment is being allowed to undertake clinical activities from which you can learn (activities at your level of competence, or slightly beyond it) (see Fig. 11 and Table 6).

Question 17. Monitoring

Monitoring is when your work is observed directly or indirectly in order to provide you with feedback and to ensure patient safety (through discussion of cases you’ve seen, checking notes you’ve written or clinical decisions you’ve made etc.) (see Fig. 12 and Table 7).

Question 19. Modelling

Modelling requires having the opportunity to observe senior doctors and other members of the healthcare team with patients (see Fig. 13 and Table 8).

Question 21. Dialogue

Dialogue is discussing patient care and other aspects of practice with senior doctors and the healthcare team (see Fig. 14 and Table 9)

Question 23. Feedback

Receiving feedback on how you performed clinical tasks (see Fig. 15 and Table 10).

Question 25. Facilities

Your learning environment may include such things as space for students (to write notes, read, and be taught) and resources (books, computers or other materials) that support your learning (see Fig. 16 and Table 11).

Question 27. Structure of the post

An appropriately structured post is one whose activities are organized in a way that supports your learning (see Fig. 17 and Table 12).

Overarching themes throughout the data

COVID 19 effects

The impact of COVID 19 was cited as an inhibitory factor on aspects of training throughout the survey at low levels. Unsurprisingly, the biggest influence this had was interference in modelling as the opportunity to share experiences is limited through decreased patient contact and through decreased contact time between trainer and trainee during the pandemic. The code counts for each question are shown in the appendix and selected quotations are shown below (see Table 13).

Workload effects

The effects of having an onerous workload were mentioned by respondents in a number of areas, namely supervision, support, entrustment, modelling, and, mostly notably, in post structure. It is apparent that in instances where the training was deemed to be poorly structured the workload burden was referenced by trainees most often. The code counts for each question are in the appendix and selected quotations are shown below (see Table 14).

Time constraints

The effects of being constrained in terms of time was noted as a factor in training in many areas but it was most marked as being a factor in supervision, dialogue, and post structure. Time management is a key skill in all areas of GP, but the management and utilisation of time in an efficient manner can have a bearing on training as is noted by trainees in their commentary below. The code counts for each question are shown in the appendix with sample quotes below (see Table 15).

Discussion

Population demographics

The study population was predominantly female (64%) and aged over 30 years old. More respondents were based in group practices (74%) and in urban settings (41%). Only 33% had enrolled on a prior training scheme. This implies that GP remains a first-choice long-term career for the majority of trainees.

Trainee perceptions of their GP learning environment

Overall, the current study demonstrates a high level of satisfaction by GP trainees with GP training as it is carried out in Ireland today. Trainees’ growth is founded on a strong but flexible and well-supported learning environment which incorporates a non-hierarchical relationship between trainers and trainees [8]. Accordingly, there is a common thread in the positive observations noted in the qualitative section in the positive language used to depict this type of trainer.

Patterns, strengths, and weaknesses in training

A number of areas of training noted in the results section were of particular interest to the current study. It is revealing to look at the pattern of results in these areas, which are listed below.

-

GP training quality is not likely to be a factor in GP emigration

A lack of training quality among NCHDs was seen as one of the major causative systemic factors contributing to doctors deciding to emigrate [9]. In this study, it is shown that poor training is unlikely to be a factor in GP emigration. Overall MCPIadapted scores of 83% with an encouraging distribution towards positive responses compares favorably with international scores on training from the UK, where overall National Trainee Survey respondents had an 83% rate of satisfaction as either good or excellent [10].

-

The current GP trainer-trainee feedback mechanisms are adequate

In terms of overall feedback 81.6% of respondents had a positive response, whereas only 15.2% recorded negative responses. However, the qualitative results diverge somewhat from the quantitative findings in this area. In particular, negative views on feedback outnumbered the codes for positive views for fourth-year single-handed practice-based trainees. It was also stated in the comments that in such situations it might be difficult to be negative in a one-to-one relationship and that some trainers were difficult to approach. Solutions to this issue may be to introduce more widespread use of anonymised instruments but also through the introduction of training for all parties on the use of feedback as a structured standard training tool [11, 12].

-

Trainees’ suggestions to address areas that are deficient

The questionnaire did not mandate the trainees to make suggestions to address deficiencies in training. However, aspects requiring improvement were either implied or, in some cases, specifically suggested by trainees in their responses. These were most notable in four specific areas of the questionnaire.

First, in supervision some trainees noted a lack of oversight and support in a few aspects including while working in out of hours settings; also, some annual leave was taken by the trainer at inappropriate times, such as when the trainee was starting the post. Secondly, in induction trainees noted a lack of a formal induction where in some cases there was no introduction to other staff members, no IT set-up or passwords ready to access the patient records system, and a lack of explanation or discussion around local care pathways or practice policies. Thirdly, some trainees reported that some resources were found wanting and basic infrastructure which is mandated by the ICGP to be available for the trainee was not in place. The final and most notable area was in the definition of roles and responsibilities. Some trainees noted that clear goal setting was not addressed and in one case the trainee was unsure even what the standard for passing was.

Are there differences in training standards based on location or practice type?

Any differences noted in location or practice type were marginal and in effect would not amount to a significant practical difference in training standards. The lack of a significant difference in scores represents the excellent work being done in all locations and in all practice types in this regard.

Qualitative themes

Outside of the broadly strong praise for the excellent efforts being made by trainers, three common themes were developed throughout the study within the coded qualitative responses: the impact of COVID19, time constraints, and excessive workload. These were unsurprising as they are challenges which were encountered by all healthcare professionals. As far back as 2007 stress management, team working, and workload were all factors which were identified as a challenge to GP training and that remains the same today in the midst of a pandemic [13].

Most of the codes in relation to COVID19 are noted under the modelling section as the usual side by side working arrangements which allow effective monitoring were disrupted. Similarly, excessive workload comments centred on poorly structured posts and trainees broadly commented that at times they felt they were overloaded. These effects were also mentioned by respondents in relation to supervision, support, entrustment, and modelling. Time constraints were most notable in the areas of supervision, dialogue, and post structure with many stating that it was a ‘busy practice’ which is reflective of real-world general practice today.

Study design and methodology

-

Study strengths

The study structure and methodology were appropriate. The structure addressed the research questions stated and the methodology for this was appropriate.

This is the first study of its kind to employ a mixed methodology in studying the perceptions of GP trainees’ learning environment in postgraduate training in Ireland. The research tool chosen was short yet comprehensive which allowed it to be more flexible and accessible to trainee respondents.

-

Study limitations

There were limitations to the study design and procedures. The study tool used was an adaptation of the original version. Although adapted after an expert panel review, it was not validated for the study population in postgraduate GP training itself. The study instrument used was somewhat rigid in nature. Respondents were forced to think a response framed by the nature of the questions rather than develop their own personal rhetoric.

The structure was somewhat limited in gaining more depth to the study responses. By design, this survey type takes a snapshot of the sample population and cannot determine correlations. The survey did not include the opinions of GP trainers as it was beyond the scope of the current work. It would be interesting and worthwhile to include their views in future research to give a more global perspective and to help investigate deficiencies in the training environment from the trainers’ perspective. The restrictive nature of the ethical approval process meant that it was not possible to contact any respondents after the survey was completed and thus precluded member checking which would have been a valuable tool to explore the credibility of the qualitative results.

Conclusions and recommendations

The current research findings were broadly positive and supportive of the good work being done in GP training and by trainers in Ireland today. Further research will be needed to validate the study instrument and to further refine some aspects of its configuration. The implementation of such a survey on a regular basis may have merit as part of the quality assurance process in GP education alongside existing feedback structures [2].

Data Availability

Please contact the lead author regarding any queries about the data set used in this study.

References

Rothlind E, Fors U, Salminen H et al (2020) The informal curriculum of family medicine–what does it entail and how is it taught to residents? A systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 21:1–10

Cushing A, Abbott S, Lothian D et al (2011) Peer feedback as an aid to learning – What do we want? Feedback. When do we want it? Now! Medical Teacher 33:e105-e112. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2011.542522

Curran T (2019) Trainees’ perceptions of course quality in postgraduate General Practice training in Ireland Project Proposal. University of Dundee,

Curran T, Hanley K (2020) Email from Dr Karena Hanley October 2020.

Dornan T, Muijtjens A, Graham J et al (2012) Manchester Clinical Placement Index (MCPI). Conditions for medical students’ learning in hospital and community placements. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Prac 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-011-9344-x

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101

Curran T, Dornan T (2021) Email from Prof Tim Dornan 2021.

Jackson D, Davison I, Adams R et al (2019) A systematic review of supervisory relationships in general practitioner training. Med Educ 53:874–885

Clarke N, Crowe S, Humphries N et al (2017) Factors influencing trainee doctor emigration in a high income country: a mixed methods study. Hum Resour Health 15:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0239-7

Gregory S, Demartini C (2017) Satisfaction of doctors with their training: evidence from UK. BMC Health Serv Res 17:851. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2792-0

Sagasser MH, Kramer AW, Van Weel C, van der Vleuten CP (2015) GP supervisors’ experience in supporting self-regulated learning: a balancing act. Adv Health Sci Educ 20:727–744

Sheri K, Too JYJ, Chuah SEL et al (2019) A scoping review of mentor training programs in medicine between 1990 and 2017. Med Educ Online 24:1555435

O’Riordan M, Mulrooney A (2007) Challenges facing general practice: are they being met by postgraduate training? Educ Prim Care 18:58–66

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the help of Professor Tim Dornan and Dr Deirdre Bennett who kindly provided the research instrument provided in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by a bursary from the Irish College of General Practitioners.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Quantitative Data Summary for Questions 8 to 26 inclusive

Question | Frequency / Percent | Strongly agree | Agree | Somewhat agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Q8 | Frequency | 59 | 49 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Q8 | Percent | 47.2 | 39.2 | 9.6 | 0.8 | 0 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

Q10 | Frequency | 51 | 38 | 18 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

Q10 | Percent | 40.8 | 30.4 | 14.4 | 4 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.8 |

Q12 | Frequency | 64 | 39 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Q12 | Percent | 51.2 | 31.2 | 12.8 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0 |

Q14 | Frequency | 54 | 56 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Q14 | Percent | 43.2 | 44.8 | 7.2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

Q16 | Frequency | 44 | 43 | 23 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

Q16 | Percent | 35.2 | 34.4 | 18.4 | 4 | 4 | 1.6 | 2.4 |

Q18 | Frequency | 31 | 35 | 25 | 12 | 13 | 5 | 4 |

Q18 | Percent | 24.8 | 28 | 20 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 4 | 3.2 |

Q20 | Frequency | 64 | 40 | 15 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

Q20 | Percent | 51.2 | 32 | 12 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.8 |

Q22 | Frequency | 37 | 44 | 21 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 3 |

Q22 | Percent | 29.6 | 35.2 | 16.8 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 2.4 |

Q24 | Frequency | 47 | 36 | 20 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 |

Q24 | Percent | 37.6 | 28.8 | 16 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 0.8 |

Q26 | Frequency | 45 | 41 | 22 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

Q26 | Percent | 36 | 32.8 | 17.6 | 4 | 4 | 4.8 | 0.8 |

Quantitative data summary for each individual question by year of training

Question | Year of training | Strongly Agree | Agree | Somewhat Agree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Q8 | 3 | 44.44 | 44.44 | 9.26 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 |

Q8 | 4 | 49.3 | 35.21 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 0 | 1.41 | 2.82 |

Q10 | 3 | 38.89 | 27.78 | 20.37 | 0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 5.56 |

Q10 | 4 | 42.25 | 32.39 | 9.86 | 7.04 | 1.41 | 2.82 | 4.23 |

Q12 | 3 | 51.85 | 33.33 | 11.11 | 3.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Q12 | 4 | 50.7 | 29.58 | 14.08 | 1.41 | 2.82 | 1.41 | 0 |

Q14 | 3 | 40.74 | 44.44 | 12.96 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Q14 | 4 | 45.07 | 45.07 | 2.82 | 1.41 | 2.82 | 1.41 | 1.41 |

Q16 | 3 | 27.78 | 44.44 | 20.37 | 3.7 | 1.85 | 0 | 1.85 |

Q16 | 4 | 40.85 | 26.76 | 16.9 | 4.23 | 5.63 | 2.82 | 2.82 |

Q18 | 3 | 22.22 | 31.48 | 20.37 | 11.11 | 11.11 | 1.85 | 1.85 |

Q18 | 4 | 26.76 | 25.35 | 19.72 | 8.45 | 9.86 | 5.63 | 4.23 |

Q20 | 3 | 50 | 27.78 | 16.67 | 3.7 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 |

Q20 | 4 | 52.11 | 35.21 | 8.45 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 0 | 1.41 |

Q22 | 3 | 29.63 | 38.89 | 16.67 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 5.56 | 1.85 |

Q22 | 4 | 29.58 | 32.39 | 16.9 | 2.82 | 8.45 | 7.04 | 2.82 |

Q24 | 3 | 37.04 | 29.63 | 14.81 | 7.41 | 3.7 | 7.41 | 0 |

Q24 | 4 | 38.03 | 28.17 | 16.9 | 4.23 | 7.04 | 4.23 | 1.41 |

Q26 | 3 | 37.04 | 37.04 | 16.67 | 5.56 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 0 |

Q26 | 4 | 35.21 | 29.58 | 18.31 | 2.82 | 5.63 | 7.04 | 1.41 |

Qualitative data summary for each individual question by practice location

Question | Location Type | Strongly Agree | Agree | Somewhat Agree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Q8 | Mixed | 36.67 | 50 | 13.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Q8 | Rural | 51.16 | 39.53 | 9.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Q8 | Urban | 50 | 32.69 | 7.69 | 1.92 | 0 | 3.85 | 3.85 |

Q10 | Mixed | 30 | 30 | 26.67 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 3.33 |

Q10 | Rural | 46.51 | 30.23 | 13.95 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 4.65 | 0 |

Q10 | Urban | 42.31 | 30.77 | 7.69 | 5.77 | 1.92 | 1.92 | 9.62 |

Q12 | Mixed | 53.33 | 30 | 13.33 | 3.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Q12 | Rural | 55.81 | 25.58 | 13.95 | 0 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 0 |

Q12 | Urban | 46.15 | 36.54 | 11.54 | 3.85 | 1.92 | 0 | 0 |

Q14 | Mixed | 30 | 56.67 | 13.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Q14 | Rural | 41.86 | 37.21 | 6.98 | 4.65 | 4.65 | 2.33 | 2.33 |

Q14 | Urban | 51.92 | 44.23 | 3.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Q16 | Mixed | 23.33 | 56.67 | 13.33 | 0 | 3.33 | 3.33 | 0 |

Q16 | Rural | 44.19 | 20.93 | 20.93 | 6.98 | 4.65 | 2.33 | 0 |

Q16 | Urban | 34.62 | 32.69 | 19.23 | 3.85 | 3.85 | 0 | 5.77 |

Q18 | Mixed | 30 | 20 | 23.33 | 10 | 10 | 6.67 | 0 |

Q18 | Rural | 20.93 | 27.91 | 27.91 | 4.65 | 13.95 | 4.65 | 0 |

Q18 | Urban | 25 | 32.69 | 11.54 | 13.46 | 7.69 | 1.92 | 7.69 |

Q20 | Mixed | 40 | 40 | 13.33 | 6.67 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Q20 | Rural | 58.14 | 23.26 | 13.95 | 2.33 | 0 | 0 | 2.33 |

Q20 | Urban | 51.92 | 34.62 | 9.62 | 0 | 3.85 | 0 | 0 |

Q22 | Mixed | 23.33 | 43.33 | 16.67 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 3.33 | 0 |

Q22 | Rural | 41.86 | 25.58 | 13.95 | 2.33 | 6.98 | 9.3 | 0 |

Q22 | Urban | 23.08 | 38.46 | 19.23 | 1.92 | 5.77 | 5.77 | 5.77 |

Q24 | Mixed | 43.33 | 23.33 | 16.67 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 3.33 | 0 |

Q24 | Rural | 34.88 | 32.56 | 18.6 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 6.98 | 2.33 |

Q24 | Urban | 36.54 | 28.85 | 13.46 | 7.69 | 7.69 | 5.77 | 0 |

Q26 | Mixed | 30 | 30 | 23.33 | 13.33 | 0 | 3.33 | 0 |

Q26 | Rural | 41.86 | 34.88 | 11.63 | 0 | 4.65 | 6.98 | 0 |

Q26 | Urban | 34.62 | 32.69 | 19.23 | 1.92 | 5.77 | 3.85 | 1.92 |

Quantitative data summary for each individual question by practice type

Question | Location Type | Strongly Agree | Agree | Somewhat Agree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Q8 | Group | 48.39 | 37.63 | 10.75 | 1.08 | 0 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

Q8 | Single | 43.75 | 43.75 | 6.25 | 0 | 0 | 3.13 | 3.13 |

Q10 | Group | 37.63 | 30.11 | 17.2 | 4.3 | 3.23 | 3.23 | 4.3 |

Q10 | Single | 50 | 31.25 | 6.25 | 3.13 | 0 | 3.13 | 6.25 |

Q12 | Group | 46.24 | 36.56 | 12.9 | 3.23 | 1.08 | 0 | 0 |

Q12 | Single | 43.75 | 43.75 | 6.25 | 0 | 3.13 | 3.13 | 0 |

Q14 | Group | 41.94 | 48.39 | 8.6 | 0 | 1.08 | 0 | 0 |

Q14 | Single | 46.88 | 34.38 | 3.13 | 6.25 | 3.13 | 3.13 | 3.13 |

Q16 | Group | 33.33 | 35.48 | 20.43 | 5.38 | 3.23 | 1.08 | 1.08 |

Q16 | Single | 40.63 | 31.25 | 12.5 | 0 | 6.25 | 3.13 | 6.25 |

Q18 | Group | 26.88 | 26.88 | 19.35 | 9.68 | 10.75 | 4.3 | 2.15 |

Q18 | Single | 18.75 | 31.25 | 21.88 | 9.38 | 9.38 | 3.13 | 6.25 |

Q20 | Group | 48.39 | 34.41 | 11.83 | 3.23 | 2.15 | 0 | 0 |

Q20 | Single | 59.38 | 25 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.13 |

Q22 | Group | 30.11 | 35.48 | 16.13 | 3.23 | 7.53 | 6.45 | 1.08 |

Q22 | Single | 28.13 | 34.38 | 18.75 | 3.13 | 3.13 | 6.25 | 6.25 |

Q24 | Group | 37.63 | 29.03 | 15.05 | 4.3 | 6.45 | 6.45 | 1.08 |

Q24 | Single | 37.5 | 28.13 | 18.75 | 9.38 | 3.13 | 3.13 | 0 |

Q26 | Group | 37.63 | 32.26 | 19.35 | 4.3 | 3.23 | 3.23 | 0 |

Q26 | Single | 31.25 | 34.38 | 12.5 | 3.13 | 6.25 | 9.38 | 3.13 |

Distribution of MCPIadapted Scores

Subdividing Factor | N | Median | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Overall total | 125 | 83.333 | 73.333 | 95 |

Year 3 | 54 | 84.167 | 75 | 93.333 |

Year 4 | 71 | 81.667 | 71.667 | 96.667 |

Group Practice | 93 | 83.333 | 71.667 | 95 |

Single handed | 32 | 82.5 | 74.167 | 92.5 |

Mixed rural–urban | 30 | 80 | 70 | 90 |

Rural | 43 | 85 | 71.667 | 96.667 |

Urban | 52 | 84.167 | 73.333 | 90.833 |

A: Q9 Supervision | |

B: Q11 Reception | |

C: Q13 Support | |

D: Q15 Entrustment | |

E: Q17 Monitoring | |

F: Q19 Modelling | |

G: Q21 Dialogue | |

H: Q23 Feedback | |

I: Q25 Facilities | |

J: Q27 Structures | |

Figure 17. Workload related Codes | |

A: Q9 Supervision | 10 |

B: Q11 Reception | 1 |

C: Q13 Support | 3 |

D: Q15 Entrustment | 0 |

E: Q17 Monitoring | 2 |

F: Q19 Modelling | 4 |

G: Q21 Dialogue | 8 |

H: Q23 Feedback | 3 |

I: Q25 Facilities | 1 |

J: Q27 Structures | 6 |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Curran, TI., Scopes, J., Hanley, K. et al. Trainees’ perceptions of course quality in postgraduate General Practice training in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 192, 2861–2879 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-023-03350-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-023-03350-5