Abstract

Objective

This study aims to understand the learning preferences and perception of medical laboratory technologists on sudden shift from offline to online training sessions during COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Microsoft form containing twenty-four questions was circulated to the twenty-five laboratory technologists after 1 year of online continuous professional development training. VARK questionnaire was circulated to understand the learning style.

Results

Provision of recording lectures, significant reduction of performance anxiety, anxiety associated with criticism, and QA sessions emerged as the major positive aspects of a virtual training platform. Analysis of learning preferences revealed that most technologists had a unimodal aural (45%) or kinesthetics (33%) than visual (11%) and reading (11%) learning preference. In bimodal learning preference, AK (44.44%) emerged as the predominant form. Forty percent of the technologists showed trimodal learning pattern with 50% among them showing an ARK pattern while 25% each showing VAK and VRK patterns of learning preferences.

Conclusion

Medical laboratory technologists adapted well to the sudden shift from offline to online continuous development programs. However, efficient managerial mechanisms to address the major perceived hurdles and designing a multimodal training module to accommodate the learning preferences of our technologists can ensure enthusiastic participation and effective learning among medical laboratory technologists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Medical laboratory technologists play a crucial role in every clinical laboratory team. Considering the ever-changing scope of practice and technological breakthroughs in the medical sciences, health professional boards around the world are increasingly asking practitioners to record and report their participation in ongoing professional development to maintain competence. The same enforcement is required for medical laboratory technologists. The scheme, scope, and frequency of professional development training vary from one laboratory to another and are also influenced by regional and national guidelines. In India, two main accreditation bodies, NABH (hospital accreditation) and NABL (National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories), govern the working framework of all the hospital based as well as stand-alone diagnostic centers and laboratories. The NABL (exclusive laboratory accreditation) provides nondiscriminatory and voluntary accreditation services to medical testing laboratories under ISO 15189 “Medical laboratories—requirements for quality and competence” guidelines which mandate NABL accredited medical laboratories to provide for continual professional development training, interaction, and assessment programs that reinforce and upgrade the knowledge, awareness, and practical applicability in medical laboratory technologists, the backbone of diagnostic laboratories as per the NABL clause 5.5 [1,2,3].

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly changed the mode of delivery of education. As the saying goes “Education cannot wait,” a circumstance-based abrupt shift from face-to-face knowledge transfer and teaching programs to online learning platforms was initiated in all pedagogical and up-gradation/training programs which ensured uninterrupted continuing professional development training of medical laboratory technologists [4]. However, unlike under graduation and post-graduation educational programs, medical laboratory technologists come from varying educational, socio-economic, and regional backgrounds, and a shift to a virtual platform of training and professional development programs might be challenging for a section of the laboratory technologists [5].

Medical laboratory technologists might also differ in their preferred methods of acquiring, processing, and recalling new information, and the period of knowledge retention. While the global pandemic makes a virtual platform of knowledge transfer indispensable, it is essential to understand the learning preferences of our target audiences (technologists or students) so that continuing professional development programs are delivered most effectively and engagingly to them. VARK (visual, aural, read/write, kinesthetic) questionnaire has long been a guide to gaining insight into learning preferences which aid the trainer to plan effective audience-tailored strategies to deliver professional development programs [6,7,8].

Although it is well acknowledged that medical laboratory technologists form the backbone of laboratory medicine and continual knowledge up-gradation, professional development programs are essential to update their skills and knowledge base. There is a dire need to explore whether our technical workforce is adapting well to the virtual knowledge exchange patterns, understand their learning styles and preferences, and attempt a tailored teaching approach that best suits and accommodates the learning needs of all our laboratory technologists. This study, therefore, attempts to fill these gaps and aims to understand the learning preferences and perceptions of medical laboratory technologists on the sudden shift from offline to online continuing professional development training sessions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional descriptive survey study was conducted after obtaining approval from the institutional ethics committee, involving 25 medical laboratory technologists working in the Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory of a tertiary care hospital. The Microsoft form with 24 questions to understand the perceptions of online versus offline continuing professional development training. The questionnaire was validated before commencing the study; 5 subject experts were asked to evaluate the questionnaire, and their feedback was incorporated; then, a total of 10 technologists were asked to answer the question, and these technicians’ responses were not used for the analysis of the current study. The Likert scale was used for 18 questions (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree) and analyzed using descriptive statistics, expressed in frequency (%). Five open-ended questions and one closed-ended question were used to understand the positive and negative aspects of online and offline presentation or training sessions. Based on the feedback, Cronbach’s alpha and frequency distribution were calculated.

VARK questionnaire (https://vark-learn.com/the-vark-questionnaire/) was given to twenty-five medical laboratory technologists to understand their learning style preferences. The completion of the questionnaire was considered as the obtainment of informed consent. The questionnaire consisted of sixteen multiple-choice questions, each with four options. The medical laboratory technologists were asked to choose more than one option if more than one answer was applicable. The distribution of the VARK preferences was calculated according to the guidelines provided on the VARK website. Accordingly, learning preferences were categorized as unimodal (V, A, R, or K), bimodal (VA, VR, VK, AR, AK, and RK), and trimodal (VAR, VAK, VRK, and ARK), or quad modal (VARK).

Results

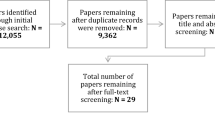

The survey included 25 laboratory technologists working in the Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory, out of which 8 were males and 17 were females. The questionnaire was divided into questions regarding positives or enablers in an online training mode and questions regarding benefits of traditional offline training platforms and negatives associated with online training. Post survey, the internal reliability of the questionnaire was found to be 0.53 and 0.59, respectively, for the two parts. Figure 1 shows the preferred mode of professional development and training programs among our laboratory technologists.

Table 1 summarizes the responses of technologists to questions regarding online training platforms. While 24% of the technologists agreed that they did not prefer an online mode of presentation, 44% were neutral about it. Most of the technologists (28%: strongly agreed; 48%: agreed) opined that high-speed internet was an essential requirement to participate in online training platforms. About half of the technologists opined (12%: strongly agreed; 44%: agreed) that it was difficult to concentrate on an online presentation platform. Participants were neutral when asked about the increased monotony (56%) and colleagues being more critical (65%) in the online mode of presentation.

Further, we asked about offline/face-to-face presentations or training, and most technologists opined those offline presentations required more concentration (16%: strongly agreed; 60%: agreed) and provided a better idea of the audience reception and response (20%: strongly agreed; 60%: agreed). Only 36% felt that there was less peer involvement in offline presentations, while 30% felt that there were more distractions during offline presentations, while 24% of technologists were neutral about it.

Open-ended questions on the perceived positives and negative aspects of virtual/ online presentations/training and professional development programs revealed the following predominant themes/ patterns (Table 2).

Open-ended questions on the perceived positives and negative aspects of traditional offline classroom-based presentations/training and professional development programs revealed the following predominant themes/patterns (Table 3).

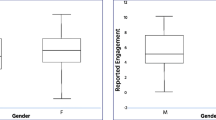

The VARK questionnaire was administered to 25 technologists working, out of which 8 were males and 17 were females. Most of our technologists showed unimodal learning preferences (Fig. 2).

AK emerged as the predominant bimodal learning preference among our technologists (Fig. 3).

VARK trimodal analysis: 40% of the technologists showed a trimodal learning pattern with 50% of them showing an ARK pattern, while 25% each showed AK and VRK patterns of learning preferences.

Discussion

Medical laboratory technologists are at the forefront of diagnostics, preventive, and public health services. On-going education and training for medical laboratory technologists must continue to receive training to remain competent in the ever-changing realms of medicine and health [9]. With laboratory medicine assuming a significant role in diagnostics, the laboratory scientists and laboratory technologists have assumed critical responsibilities of adapting to new equipment, methodologies, and automation, analyzing, interpreting laboratory tests, raising critical value alerts, implementing quality assurance programs, and significantly participate in patient care, education, and research [10].

Our study revealed that most of the technologists were comfortable with both offline and online modes of presentation and training programs; however, 24% of the technologists preferred the traditional offline training program. This might be due to the predominant aural learning preference among technologists and the lack of high-speed internet or a compatible phone/laptop. Most of them opined that presentation in online mode was easier, significantly reduces performance pressure/imposter syndrome due to the virtual platform, caused lesser distractions (due to environmental factors), helped maintain composure while Question and Answer sessions, and was easier to deal with criticisms. The provision of recording an online presentation/training was considered beneficial and future reference to a recorded training might be an effective means of learning, reinforcement, and recall in aural learners. Requirement for a high-speed internet facility and difficulty in maintaining concentration while other colleagues or trainers present emerged as the main hindrances of a virtual training/presentation platform. However, traditional offline presentations required more concentration and needed greater measures to deal with performance anxiety but also provided a better idea of the audience's reception and response. Analysis of learning preferences revealed that most of our technologists had a unimodal aural or kinesthetic learning preference with AK pattern being the predominant bimodal learning preference and ARK pattern being the predominant trimodal preference (Figs. 2 and 3). This analysis is significant while designing activities, handouts, and reference materials to ensure effective training and reinforcement.

The NABH and NABL guidelines which govern diagnostic laboratories are based on ISO 15189 guidelines and require intensive quality assurance and procedural documentation not only of the diagnostic test procedures but also of the employees who form a part of the laboratory including the medical lab technologists. The guidelines emphasize that knowledge must be maintained and accessible to the extent necessary. (ISO 9001:2015 7.1.6). The health care personnel must have received comprehensive and current training in their duties. (ISO 9001:2015 7.2). Personnel that are undergoing training shall be always supervised and the effectiveness of the training program shall be periodically reviewed. (ISO 15189:2012 5.1.5). In addition to the assessment of technical competence, the laboratory shall ensure that reviews of staff performance consider the needs of the laboratory. This improves and maintains the quality of service given to the users and encourages productive working relationships. (ISO 15189:2012 5.1.7) [11]. Hence, professional development programs, training, and knowledge exchange programs are indispensable parts of laboratory medicine.

A study by Fisher and Britt reported a significant percentage of laboratory technical staff require continuing professional development programs in the major technical categories, quality assurance, laboratory management, and supervision [12]. Research reveals that internet-based professional development programs aid in increasing training efficacy and development of professional skills [13, 14]. Continuing professional development programs also increase cooperation and ensure career development (promotions/incentives/better job opportunities) [15]. Further, repeatable, interactive interventions ensure reinforcement, recall, and cooperative learning leading to better knowledge outcomes [16]. With the rapid transformations reshaping the education system, there is a shift in focus towards learner-friendly education and a heutagogy-based learning environment. Learners vary in their learning styles and preferences, and effective learning ensures identifying learning needs and adopting numerous learning strategies to accommodate the learning needs of everyone. Learning preferences of a population can be variable and may also differ across the streams of education. For example, a study by Murphy et al. on VARK preferences of dental students reported that dental students prefer a higher percentage of visual learning and lesser kinesthetic learning when compared to the sample VARK student population [17].

Science-based streams including healthcare education are usually better understood and reinforced through observations, experiments, and practical sessions. This study showed a predominant aural and kinesthetic learning preference among laboratory technologists. Similar study on life science students reported that practical sessions were the most preferred learning strategy (kinesthetic and hands-on approach) in these students [18]. Multimodal learning strategies providing opportunities for visualization, listening, observing, and reinforcing might aid better learning and retention in health care professionals. A study reported significant improvement in students’ satisfaction when virtual learning methods were incorporated in teaching sessions and students reported that visuals were helpful in understanding and knowledge retention in health care education [19]. Students usually are reported to demonstrate multimodal learning preferences with reading/writing followed by kinesthetic being the most dominant learning style with no gender-specific differences. Further learning preferences are reported to evolve and might need to be assessed periodically to ensure an inclusive environment. The study also emphasized that most students learn effectively provided they are equipped with multiple and varied learning activities per their VARK preferences. The author further concluded that active learning might be effectively facilitated by practical and hands-on sessions, simulation and animation models, demonstrations, discussions, debates, clicker questions, quizzes, MCQs, and role-playing [20].

Medical laboratory technologists are aware of the dynamic and ever-evolving nature of their profession and recognize the indispensable importance of continual professional development (CPD) programs. CPDs are essential for the development of practical skills for adapting to technological advancement, troubleshooting, quality assurance, and time management are vital in health care. The present study showed high-speed internet and lack of devices to be major hurdles for a few technologists to effectively participate in online CPDs [21].

A predominant aural and kinesthetic learning population, the technologists are ought to benefit from pedagogical presentations, interactives, recordings, audio or animated handouts and summaries, demonstrations, practical sessions, and animated self-assessments. Assessment of their learning preferences; designing of effective learning aids and managerial support in alleviating infrastructural, financial, and psychological hurdles to the online or mixed platform of training and professional development programs; encouraging staff conducted sessions; and creating a safe classroom cohort (free from penalties, punishments, and destructive criticisms) can ensure enthusiastic participation and effective learning. A flexible multiple modal and incentivizing format of CPDs addressing the concerns and the learning requirements of the staff and providing an opportunity for self-assessment, improvement, and iterative learning are thus essential while planning for professional development programs, especially in the online era [21].

Conclusion

To conclude medical laboratory technologists are keen to adapt to the virtual/online training platform for professional development and up-gradation programs, the supervisors must be careful in providing required organization and numerous training modules/materials and aids to ensure effective learning and maximum engagement of technologists in virtual continuous professional development programs. The trainer/presenter acknowledged and understood there is no single right way to effectively communicate/train/teach any topic; however, implementing multiple approaches to accommodate the different learning preferences and ensuring feasibility can improve the effectiveness and workforce engagement of training/presentation in medical laboratory technologists.

Limitations

The major limitation of this study was the size of study population; hence, the study can be continued further by expanding the study period and including different primary care facilities and laboratories. Also, a follow-up study to further access the efficacy of online learning is required as this study was predominantly conducted during the COVID 19 pandemic which could have caused bias due to limited learning experiences.

Data availability

The data generated during the research and analysis are not available publicly but are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- VARK:

-

Visual, Aural, Read/write, and Kinesthetic

- QA:

-

Question answer session

- NABH:

-

National Accreditation Board for Hospitals

- NABL:

-

National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories

- CPD:

-

Continual professional development

References

Kasvosve I, Ledikwe JH, Phumaphi O et al (2014). Continuing professional development training needs of medical laboratory personnel in Botswana. Hum Resour Health 12(46). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-12-46

Fonjungo PN, Kebede Y, Arneson W et al (2013) Preservice laboratory education strengthening enhances sustainable laboratory workforce in Ethiopia. Hum Resour Health 11(56). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-56

National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL) (2019). Specific criteria for accreditation of medical laboratories (Internet). Haryana: NABL. (cited on 20 July 2021). 47 p. Report No.: 112. Available from: https://www.nabl-india.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/NABL-112_Issue-3_Amd-_06.pdf

Dhawan S (2020). Online Learning: A Panacea in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis. J Educ Technol Syst 49(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018. PMCID: PMC7308790. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7308790/

Tan KB, Thamboo TP, Lim YC (2007). Continuing education for pathology laboratory technologists: a needs analysis in a Singapore teaching hospital. J Clin Pathol 2007;60(11):1273–1276. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2006.045195. Epub 16 Feb 2007. PMID: 17307865; PMCID: PMC2095468. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2095468/

Kharb P, Samanta PP, Jindal M, Singh V (2013). The learning styles and the preferred teaching-learning strategies of first year medical students. J Clin Diagn Res 7(6):1089–1092. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2013/5809.3090. Epub 22 Apr 2013. PMID: 23905110; PMCID: PMC3708205. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3708205/

Bahadori M, Sadeghifar J, Tofighi S et al (2011) Learning styles of the health services management students: a study of first-year students from the medical science universities of Iran. Aust J Basic Appl Sci 5(9):122–127

Sternberg RJ, Grigorenko EL, Zhang LF (2008) Styles of learning and thinking matter in instruction and assessment. Perspect Psychol Sci 3(6):486–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00095.x. PMID: 26158974

Ifeoma EA, Rebecca EF, Ezekiel OO et al (2015) A cross-sectional study of the knowledge and attitude of medical laboratory personnel regarding continuing professional development. Niger Med J 56(6):425–428. https://doi.org/10.4103/0300-1652.171617. PMID: 26903702; PMCID: PMC4743294

Kotlarz Virginia R (2001) Tracing our roots: new opportunities and new challenges in clinical laboratory science (1977–1992). Clin Lab Sci Bethesda 14(1):13–18

Standards (Internet) (1946). Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization. ISO 15189:2012 Medical laboratories — requirements for quality and competence; 2012 (25 July 2021); (1–53). Available from: https://www.iso.org/standard/56115.html

Fisher F, Britt MS (1987) An assessment of continuing education needs for clinical laboratory personnel. Laboratory Medicine 18(2):110–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/labmed/18.2.110

Horiuchi S, Yaju Y, Koyo M et al (2009). Evaluation of a web-based graduate continuing nursing education program in Japan: a randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ Today 29(2):140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2008.08.009. Epub 1 Oct 2008 PMID: 18829141. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18829141/

Martin F, Doris UB (2018) Engagement matters: student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learn 22(1);205–222. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1179659

Ali S, Lu W, Wang W (2012) Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among the college students in China, and Pakistan. J Educ Pract 3(11):13–21. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234633594.pdf

Cervero RM, Gaines JK (2015) The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof 35(2):131–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21290. PMID: 26115113

Murphy RJ, Gray SA, Straja SR, Bogert MC (2004) Student learning preferences and teaching implications. J Dent Educ 68(8):859–866

Meehan-Andrews TA (2009) Teaching mode efficiency and learning preferences of first-year nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 29(1):24–32

Ryan E, Poole C (2019) Impact of virtual learning environment on students’ satisfaction, engagement, recall, and retention. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci 50(3):408–415

Alkhasawneh IM, Mrayyan MT, Docherty C et al (2008) Problem-based learning (PBL): Assessing students’ learning preferences using vark. Nurse Educ Today 28(5):572–579

Amanda V, Hilary M (2015) Medical laboratory technologists’ experiences with continuing professional development. Can J Med Lab Sci Hamilton 77(1):22–26

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors MB, RM, VBS, VSB, VJ, G, and KNP conceptualized the study. MB, VBS, RM, KNP, and VJ wrote the first draft. RM, G, VBS, KNP, MB, VJ, and VSB analyzed and interpreted the data. All the authors (RM, VJ, KNP, VBS, MB, G, and VSB) contributed to its administration, discussion, conclusion, and critical revision. All authors approve the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Biswas, M., Belle, V.S., Geetha et al. VARK preference and perception of online versus offline professional development training of medical laboratory technologists. Ir J Med Sci 192, 2337–2343 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03251-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03251-z