Abstract

Introduction

The significance of ring-fencing orthopaedic beds and protected elective sites has recently been highlighted by the British Orthopaedic Association and the Royal College of Surgeons. During the pandemic, many such elective setups were established. This study aimed to compare the functioning and efficiency of an orthopaedic protected elective surgical unit (PESU) instituted during the pandemic with the pre-pandemic elective service at our hospital.

Methods

We retrospectively collected data of all patients who underwent elective orthopaedic procedures in PESU during the pandemic and a similar cohort of patients operated on via the routine elective service immediately prior to the pandemic. To minimise the effect of confounding factors, a secondary analysis was undertaken comparing total hip replacements by a single surgeon via PESU and pre-pandemic ward (PPW) over 5 months.

Results

A total of 192 cases were listed on PESU during the studied period whereas this number was 339 for PPW. However, more than half of those listed for a surgery on PPW were cancelled and only 162 cases were performed. PESU had a significantly better conversion rate with only 12.5% being cancelled. Forty-nine percent (87 out of 177) of the cases cancelled on PPW were due to a ‘bed unavailability’. A further 17% (30/177) and 16% (28/177) were cancelled due to ‘emergency case prioritisation’ and ‘patient deemed unfit’, respectively. In contrast, only 3 out of the 24 patients cancelled on PESU were due to bed unavailability. Single-surgeon total hip replacement showed similar demographic features for the 25 patients on PESU and 37 patients on PPW. The patients on PESU also demonstrated a decrease in length of hospital stay with an average of 3 days.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As per the latest statistics, more than 600,000 people are waiting for elective surgeries in Wales [1]. This means 1 in 5 Welsh citizens are waiting for some form of elective surgical care. Within this group, approximately 100,000 are waiting for orthopaedic procedures, a significant proportion being knee and hip replacements. A recent study pointed out that a third of patients waiting for hip arthroplasty stated that they were in ‘worse than death’ situation and the number of people in this category has doubled in 2 years of the pandemic [2]. The waiting list numbers are the highest ever recorded since the National Health Service (NHS) Improvement Plan set out requirements from referral to treatment [3]. On reviewing the last 10 years of data, we can appreciate a slow but steady rise in the numbers which has been worsened by the pandemic. Therefore, the elective waiting list has been a smouldering issue which has been set ablaze by the pandemic rather than a new problem (Fig. 1). Even prior to the pandemic, reports on the future projections for hip and knee replacements in the United Kingdom (UK) show an exponential rise which could overwhelm the National Health Service capacity by 2035 [4]. Many surgical sites are still in a standstill mode for elective orthopaedic procedures during the drafting of this article, and we are quite evidently heading towards if not already arrived at the perfect storm.

The consensus from British Orthopaedic Association and the Royal College of Surgeons has been pointing towards the need for protected elective operating sites [5, 6]. Dedicated orthopaedic elective centres like the South West London Elective Orthopaedic Centre has continued functioning even through the pandemic. The Getting it right first time (GIRFT) statement reinforces the improved outcomes for patients with green elective sites in parameters such as wound infection and shorter duration of stay [7].

As an initial response to COVID-19 pandemic, many smaller protected elective operating systems were introduced within hospitals. In our hospital, the ‘Protected Elective Surgical Unit’ (PESU) was one such unit with a ring-fenced, mixed-sex, eight-bed facility within one of three District General Hospitals within the Health Board where, along with routine orthopaedic Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) screening, protocol required that patients had a negative COVID PCR test and were in self-isolation prior to coming to the hospital. There were dedicated staff with no cross-covering and thereby keeping cross-contamination to a minimum. Surgery was undertaken within a dedicated laminar air flow theatre, remote from the hospital general theatre suite. Prior to the pandemic, elective orthopaedic surgery was undertaken in the same theatre and although from an MRSA ring-fenced ward, it shared many facilities such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy and nursing staff and commonly receiving screened trauma cases (pre-pandemic ward (PPW)).

Materials and methodology

We retrospectively collected data of all patients listed for all elective orthopaedic procedures under PESU between March 2020 and June 2020, and for a fair comparison, we looked at a similar period of time immediately prior to the pandemic from the PPW between October 2019 and February 2020. We looked at patient-related parameters such as length of stay, Patient reported outcome measures PROMs and readmissions or complications. From a logistical perspective, we looked at cancellations and reasons for cancellations. Due to the retrospective nature of the study and with care taken to ensure no patient identifiers are used, ethical approval was not sought. The study was registered as a service evaluation project with the Trust and is being reported according to the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE 2.0) guidelines [8].

Results

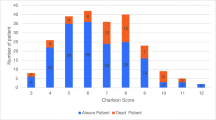

A similar number of procedures were performed via the PPW versus the PESU (168 cases in PESU and 162 in PPW). However, the cancellations were four times higher in PPW. Among the 192 patients listed in PESU, there were 24 cancellations (12.5%), whereas 48% procedures were cancelled in PPW (339 cases listed and 177 cancelled). Investigating the reason for cancellations, the majority (49%, 87/177) were due to lack of availability of bed prior to the pandemic in PPW, while, during the pandemic with a dedicated unit, only three procedures were cancelled due to bed availability (less than 2%). Emergency case prioritisation accounted for 30 cancellations in PPW, but with the strict ring fencing of the PESU, it was not affected by emergency admissions. Twenty-eight patients in PPW and nine patients from PESU had surgeries cancelled due to medical reasons (Table 1). Furthermore, a handful of cancellations from PESU were due to medically unrelated issues such as leaking toilet.

To evaluate parameters that could indicate the safety and efficiency of PESU, we further segregated the data to minimize confounding variables. Data from patients undergoing the same procedure (primary total hip replacement) by the same surgeon (senior author in the article) pre-pandemic and during the pandemic via the PESU were compared. Evaluating cohorts from a matching period of time (March to July 2019 (PPW) vs. 2021 (PESU)), cohorts were found to be comparable with regards to age, American society of Anaesthesiologistphysical status classification (ASA) grade and Body mass index (BMI) (Table 2). The length of hospitalisation was found to be significantly reduced via the PESU, with average length of stay being 3 days in comparison to pre-pandemic figures, where the average was 4.8 days. The Oxford Hip Score improvement at 6 weeks’ post-operative period was marginally higher in PPW (18.8) compared to PESU (16.4). There were no cases that required readmission or revision in the PESU cohort.

Discussion

More than half a million elective operations were cancelled in the first wave of the pandemic [9]. Beyond the numbers and statistics, the human suffering and decrease in quality of life is overwhelming [2]. A young athlete waiting for an elective anterior cruciate ligament surgery could have repeated injuries during the wait and end up with an unrepairable meniscal injury which could be the end of a sporting career [10]. Similarly, studies have pointed out that undue waiting time and poor waiting list prioritisation strategy for total hip replacements are associated with deterioration of pain and functional outcome and suboptimal therapeutic effect [11, 12]. Timely intervention has also been found to be cost-effective [13].

In our data, we have shown how a dedicated ring fencing of orthopaedic elective services can decrease the cancellations, and this is in tandem with the GIRFT statement, where functioning of multiple dedicated green sites was reviewed and shown to significantly decrease ‘on the day of surgery’ cancellations [7]. The national average for length of stay following primary total hip replacement is 4.16 days as of 2020. Ring-fenced units have shown to decrease the length of stay which is one of the important outcome measures following joint replacement surgery. In our study, the average length of stay for hip replacement surgery was reduced to 3 days from 4.8 days with a ring-fenced unit. We strongly agree with the input from nursing staff who worked in PESU, who pointed out that patients were seen by physiotherapists on the day of the operation and able to get them out of bed the same day, a dedicated occupational therapy team was involved pre- and post-surgery, and as the unit was protected, nurses were able to support and encourage the patients to be more independent without having the pressure of accepting unplanned trauma admissions and their inevitable related distractions.

While trying to tackle the long waiting list, it is important to ensure that overzealous efforts do not affect the quality of care provided. In our data reviewing readmissions and revisions, no patients who had care undertaken in PESU had any such events. Although the number of cases operated on were relatively the same in either cohort, the cancellations were drastically reduced. This, in turn, means that patients waiting for elective surgery who have tested negative for COVID 19 and have completed a period of self-isolation are prevented from unnecessary exposure and the disappointment of the continued wait. When looking at the results of length of hospitalisation, PROMS, complications and readmission, it is evident that PESU was not only safe, but also effective in delivering care.

Conclusion

A complete cessation of elective services underlines the fact of how unprepared the healthcare infrastructure is with regards to disaster preparedness and future proofing. For instance, in March 2020, many services including GP practices and hospital elective services witnessed a 2-week shutdown. The pandemic must be taken as an eye opener and a retrospective analysis of service is the need of the hour. Our data shows that even a small eight-bed protected surgical unit can function much effectively with good functional outcomes as opposed to a green pathway in a general hospital ward which is susceptible to seasonal illness such as winter pressure and emergency admissions. Limitations of the study include the relatively small number of cases and short duration of follow-up. However, the findings of the study indicate evident differences and could be used as a pilot study for a larger dedicated ward separate from trauma services (cold site) which would prevent the return to previous distractions.

References

Anonymous (2022) Patient pathways waiting to start treatment by month, grouped weeks and stage of pathway. statswales gov wales https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Health-and-Social-Care/NHS-Hospital-Waiting-Times/Referral-to-Treatment/patientpathwayswaitingtostarttreatment-by-month-groupedweeks. Accessed 1 May 2022

Scott CEH, MacDonald DJ, Howie CR (2019) “Worse than death” and waiting for a joint arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 101-B(8):941–50. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.101B8.BJJ-2019-0116.R1

Anonymous (2022) Waiting times for elective (non-urgent) treatment: referral to treatment (RTT). The King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/waiting-times-non-urgent-treatment. Accessed 1 May 2022

Culliford D, Maskell J, Judge A et al (2015) Future projections of total hip and knee arthroplasty in the UK: results from the UK Clinical practice research datalink. Osteoarthr Cartil 23(4):594–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.12.022

BOA (2021) Re-starting non-urgent trauma and orthopaedic care: full guidance. www.boa.ac.uk. https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/boa-guidance-for-restart---full-doc---final2-pdf.html. Accessed 1 May 2022

Royal College of Surgeons. Report: Protecting surgery through a second wave. rcseng.ac.uk. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/coronavirus/protecting-surgery-through-a-second-wave/. Accessed 1 May 2022

Anonymous (2020) Getting It Right in Orthopaedics REFLECTING ON SUCCESS AND REINFORCING IMPROVEMENT, a follow-up on the GIRFT national specialty report on orthopaedics. Getting It Right in Orthopaedics. https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/GIRFT-orthopaedics-follow-up-report-February-2020.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2022

Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D et al (2015) SQUIRE 2.0 (standards for Quality improvement reporting excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process: BMJ Quality & Safety 25(12):986–92. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000153

Nepogodiev D, Bhangu A (2020) Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg 107(11):1440–1449. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11746

Kim SH, Han S-J, Park Y-B et al (2021) A systematic review comparing the results of early vs delayed ligament surgeries in single anterior cruciate ligament and multiligament knee injuries. Knee Surgery & Related Knee Surg Relat Res 33(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43019-020-00086-9

Vergara I, Bilbao A, Gonzalez N et al (2011) Factors and consequences of waiting times for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(5):1413–1420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1753-2

Hajat S, Fitzpatrick R, Morris R et al (2002) Does waiting for total hip replacement matter? Prospective cohort study. J Health Serv Res Policy 7(1):19–25. https://doi.org/10.1258/1355819021927638

Mujica-Mota RE, Watson LK, Tarricone R, Jäger M (2017) Cost-effectiveness of timely versus delayed primary total hip replacement in Germany: a social health insurance perspective. Orthop Rev 9(3). https://doi.org/10.4081/or.2017.7161

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. PML conceptualised the project, supervised in all stages and was involved in data analysis and proof reading. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by VJ, JGEB and KR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by VJ and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This is an observational study. The project was registered as a service evaluation with the Trust and confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joseph, V., Boktor, J.G.E., Roy, K. et al. Dedicated orthopaedic elective unit: our experience from a district general hospital. Ir J Med Sci 192, 1727–1730 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03174-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03174-9