Abstract

Background

Ending tuberculosis (TB) is a global priority and targets for doing so are outlined in the World Health Organization (WHO) End TB Strategy. For low-incidence countries, eliminating TB requires high levels of wealth, low levels of income inequality and effective TB programmes and services that can meet the needs of people who have not benefited from these and are still at risk of TB. In Ireland, numerous reports have noted a need for more funding for TB prevention and control.

Aim

The aim of this research was to estimate the cost of not meeting the WHO End TB target of a 90% reduction in TB incidence in Ireland between 2015 and 2035.

Methods

The cost of projected TB cases between 2022 and 2035 is estimated based on trends in surveillance data for the period 2015 to 2019 and outcomes reported in the literature.

Results

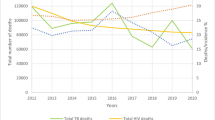

Between 2022 and 2035, it is projected that a failure to meet the WHO End TB Strategy target will result in an additional 989 cases of TB, 577.3 disability-adjusted life years and 35 deaths with TB in Ireland. The cost of this is estimated to be €70.779 million.

Conclusion

Given the estimated cost, Ireland’s current prospects of eliminating TB and the tendency towards programmatic funding internationally, greater investment in TB prevention and control in Ireland is justifiable. A national elimination strategy with actions at the levels of the social determinants of health, the health system and the TB programme should be funded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Tuberculosis (TB) is a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality [1], and its elimination is an international priority [1,2,3,4]. In 2020, 57 countries had an incidence of TB of less than 10 cases per 100,000 [1]. For these, achieving the World Health Organization (WHO) End TB Strategy target of a 90% reduction in TB incidence between 2015 and 2035 is an important stepping stone towards its elimination [2, 4]. Improving socioeconomic conditions was a major factor behind the decline of TB in the twentieth century [5]. However, more recently, in European countries, differences in national wealth and levels of income inequality explained only 50% of the between-country variation in TB burden [6]. Furthermore, although TB burdens declined to a point with improving wealth and income equality, the between-country differences in TB burden diminished [6]. Therefore, although wealth, particularly distributed wealth, is important to address TB, more is needed to eliminate it [4, 5]. In many low-incidence countries, a large proportion of people with TB are recent immigrants, often from countries with much higher burdens of TB, less wealth and more income inequality [5, 7]. Even in wealthy countries with relatively low-income inequality, TB persists (Table 1), particularly among those marginalised by society because of culture, ethnicity, lifestyle or poverty [4]. For example, in Ireland, Travellers were disproportionately affected [8], in England, people who were homeless [9], and in Canada, the incidence of TB among Inuit people is over 50 times that of the general population [10]. Therefore, for low-incidence countries, eliminating TB requires high levels of wealth, low levels of income inequality and effective TB programmes and services that can meet the needs of people who have not benefited from these and are still at risk of TB [4].

Eliminating TB in Ireland, a high-income low-incidence country, will be challenging. TB in Ireland is increasingly concentrated within marginalised groups [11]. The COVID-19 pandemic may have harmed TB control in Ireland [11]. In other low-incidence countries, during the pandemic, testing for TB decreased, TB diagnoses were delayed, patients had more severe disease at diagnosis and more household contacts had TB infection (suggesting increased transmission) [12,13,14,15]. There will probably be an increase in TB nationally, particularly drug-resistant TB, related to the arrival of people from Ukraine (where the incidence of TB was 73 cases per 100,000 prior to the war [1]) [11]. Drug-resistant TB can require prolonged multidrug treatments, which can be costly and resource-intensive to provide [2, 4, 16]. Like other low-incidence countries [17, 18], most TB in Ireland is likely due to the reactivation of latent TB infection (LTBI), which can be difficult to diagnose and treat [4]. Even without considering these factors, to achieve the WHO End TB target by 2035 in Ireland, the rate of TB incidence decline would have to double from 6.5% to 13% (Fig. 1) [19]. Compared with other low-incidence European countries, Ireland is not dissimilar in how it is currently positioned to eliminate TB (Table 1). However, other European countries are funding coordinated programmes to improve their TB programme and service delivery. Finland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy, the UK and Spain all have TB control strategies [20]. Latent TB infection screening programmes of recent migrants exist in Norway, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, France, the UK, Italy and Germany [21]. Most countries in Europe have programmes for raising awareness of TB at the community care level [20]. Ireland, like comparable countries, should be intensifying its TB control efforts. Over the previous 20 years, TB prevention and control in Ireland have been examined repeatedly, and numerous reports have made recommendations for its strengthening, often noting that activities were becoming more resource intensive and that more funding was needed [22,23,24,25]. The aim of this study was to estimate the cost of not meeting the End TB Strategy target in Ireland. This could be informative for future resource allocation decisions.

Methods

The cost of not reaching the WHO End TB Strategy target of a 90% reduction in TB incidence between 2015 and 2035 can be measured in morbidity (cases and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)), mortality, direct costs and indirect costs. This analysis estimates these measures using assumptions (Table 2) based on trends in surveillance data for the period 2015 to 2019 and outcomes reported in the literature. Direct care cost estimates were derived from a TB service in Ireland [26] and those reported in the literature (inflated to 2019 values using Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) consumer price index data for the origin country [27] and then converted to Euros (Ireland) using the purchasing power parity index as reported by the OECD [28]).

Results

Between 2022 and 2035, it is projected that a failure to meet the WHO End TB Strategy target will result in an additional 989 people having TB disease, 577.3 DALYs and 35 deaths with TB in Ireland (Table 3). The cost of not meeting the End TB target is projected to be €70.779 million between 2022 and 2035.

Discussion

This analysis estimates the future cost to Ireland of failing to achieve the WHO End Tuberculosis Strategy target of a 90% reduction in TB incidence by 2035 as being €70.779 million. Given Ireland’s current prospects of eliminating TB and the tendency towards programmatic funding in other low-incidence countries, investment in effective interventions to reduce the burden of TB in Ireland is financially justifiable. In addition, a 2015 health technology assessment estimated universal bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination to cost €2.4 million annually in Ireland and concluded that a move to a selective approach for BCG vaccination could be considered but that there was first a need to invest in other aspects of TB control [43]. BCG vaccination has since ceased in Ireland, but substantial investment in other aspects of TB control has not materialised. Of course, many would argue that funding for TB should not be viewed through such a “zero-sum” approach and that it should be much greater than this. The burden of other sequelae of TB disease for patients has been poorly evaluated in Ireland. Prolonged symptoms prior to diagnosis, stigmatization, socioeconomic consequences such as loss of housing and post-TB complications (e.g. chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, psychological ill health) [44], may mean the true cost of TB disease is much more than the monetary costs reported in this analysis.

There are several limitations to this analysis. First, it assumes that meeting the End TB Strategy target in low-incidence countries is achievable, primarily because TB is preventable and treatable. How feasible it is in Ireland to achieve the entirety of the required reduction in TB incidence by 2035 can be debated. TB economic analyses would typically describe the potential cost–benefit of an intervention based on modelling of future epidemiological scenarios with and without the intervention. Such analyses may use a Markov model which can account for uncertainty in the cost estimates and the probability of outcomes occurring [45]. TIME Impact, an epidemiological transmission modelling tool, can provide projections of future TB incidence that account for the natural history of TB, drug resistance and treatment history [46]. This analysis considered only single-point estimates from the literature for all variables, not accounting for any uncertainty in the estimates, meaning only a single-point estimate is presented as the final cost. For example, there is a large variation in the cost of drug-resistant TB care in the literature [33,34,35,36,37]. The analysis does not account for any potential detriment in TB control in Ireland related to the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in immigration patterns or changes in drug-resistant TB prevalence. Therefore, the methodology used in this analysis was simplistic. However, the primary preventive intervention in low-incidence countries is LTBI screening. In Ireland, LTBI prevalence data are lacking to reliably inform any such economic evaluations [47]. Regardless, what is clear even from this analysis is that continuing at the current rate without intervention is a costly choice. Other limitations were that the cost of any operational (e.g. surveillance) or communication and engagement activities conducted by the TB programme were not included. The direct cost of TB care and contact management may change in the future, particularly if shorter treatment regimens become the preferred standard of care. For contact management, the cost of care estimates may be an underestimate because they were calculated using a sample of medical patients with largely uncomplex needs and a high treatment completion rate [19]. A further limitation of this analysis was that future inflation was not factored into cost estimations. However, inflation of health care costs tends to be greater than that of general inflation [48]. This means that, over time, cost savings due to disease prevention become increasingly valuable relative to other costs if inflation is maintained.

Evidently, TB control in Ireland should be intensified and this is financially justifiable. Determining the actions needed should begin with the appointment of a national lead for TB elimination in Ireland, the convening of stakeholders (including patients and people at risk of TB) and the development of a national elimination strategy. This strategy should consider actions at three levels: those at the level of the social determinants of health (e.g. reducing poverty and inequality), those at the level of the health care system (e.g. providing high-quality universal healthcare, improving migrant health) and those at the level of the TB programme (e.g. reducing diagnostic delays, programmatic LTBI management and improved contact management and outbreak response). Influencing health and social policy could be challenging for stakeholders when they largely exert no control over them. However, stakeholders can still influence national policy for the better by demonstrating the harms to health of poverty, inequality and a lack of access to health care. At the level of the TB programme, delayed diagnosis has been reported in Ireland [26, 49] and, apart from potentially leading to more transmission [12, 50], probably increases care costs [26]. Strengthening non-acute care pathways between primary care and TB services will be important to address this [26], and this is consistent with the aims of Sláintecare [51]. Research explaining the causes of patient-related delays prior to diagnosis is needed [26].

Expanding LTBI screening and treatment programmatically in low-incidence countries is needed to end TB [4, 52, 53]. Preventive treatment may be targeted programmatically not only at those currently recommended for screening and treatment but also at other vulnerable population groups. In Ireland, detailed data on the prevalence of risk factors among TB cases notified are not routinely reported, and studies evaluating the effectiveness of LTBI screening in at-risk groups in Ireland are needed [47]. If Ireland is to meet the End TB target, 51 of the 56 cases per million (90%) of TB notified in the year of 2019 would have to be prevented. The feasibility of meeting the ambitious End TB target in Ireland will depend on their being high completion rates of LTBI screening and treatment. In 2019, 22% of TB cases in Ireland occurred in people aged 65 and older, and due to shifting age demographics, this proportion may increase over time [54]. Therefore, to end TB, preventive treatment will need to include older at-risk people [4]. However, for older people, the individual risk of harm from preventive treatment may outweigh the benefits [55]. Programmatic LTBI management should include close surveillance of the incidence of treatment-related adverse events in older people. Internationally, LTBI screening completion tends to be low among migrants and treatment completion low among marginalised groups [32]. Programmatic LTBI management must involve engagement with target groups to understand and overcome the reasons for declining or not completing screening and treatment.

Outbreak prevention could be strengthened by reducing overall TB incidence, reducing delayed diagnoses and improving the management of LTBI. An increase in drug-resistant TB could be a challenge for contact LTBI management because of the need for more complex-tailored preventive treatment regimens with limited evidence to support the duration of treatment choices [16]. To strengthen outbreak prevention, TB advocacy, communication and engagement, as well as testing among vulnerable populations and in institutional settings such as prisons (where large outbreaks have occurred [56]), should be improved. Outbreak response should be strengthened through the provision of additional staff, including social workers and outreach staff, to public health departments, given the increasing complexity of managing outbreaks in vulnerable populations and institutional settings.

Conclusion

The cost of not meeting the End TB target in Ireland is projected to be €70.779 million between 2022 and 2035. A national elimination strategy with actions at the levels of the social determinants of health, the health system and the TB programme should be invested in.

References

World Health Organization (2021) Global tuberculosis report. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240037021. Accessed 17 Aug 2022

World Health Organisation (2014) End TB Strategy: global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015, 2014. https://www.who.int/tb/post2015_strategy/en/. Accessed 17 Aug 2022

Zumla A, Petersen E (2018) The historic and unprecedented United Nations General Assembly High Level Meeting on Tuberculosis — united to end TB: an urgent global response to a global epidemic. Int J Infect Dis 75:118–120

Lӧnnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I et al (2015) Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J 45(4):928–952

Lӧnnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG et al (2009) Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc Sci Med. 68(12):2240–2246

Ploubidis GB, Palmer MJ, Blackmore C et al (2012) Social determinants of tuberculosis in Europe: a prospective ecological study. Eur Respir J 40(4):925–930

Lӧnnroth K, Mor Z, Erkens C et al (2017) Tuberculosis in migrants in low-incidence countries: epidemiology and intervention entry points. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 21(6):624–636

O’Toole R, Jackson S, Hanway A et al (2015) Tuberculosis incidence in the Irish Traveller population in Ireland from 2002 to 2013. Epidemiol Infect 143(13):2849–2855

Story A, Murad S, Roberts W et al (2007) Tuberculosis in London: the importance of homelessness, problem drug use and prison. Thorax. 62(8):667–671

Mounchili A, Perera R, Lee RS et al (2022) Chapter 1: epidemiology of tuberculosis in Canada. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med 6(sup1):8–21

Houston M (2022) Tuberculosis in Ireland: the re-emergence of an infectious disease due to Covid and war. Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/tb-in-ireland-the-re-emergence-of-an-infectious-disease-due-to-covid-and-war-1.4841950. Accessed 17 Aug 2022

Narita M, Hatt G, Gardner Toren K et al (2021) Delayed tuberculosis diagnoses during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020–King County. Washington. Clin Infect Dis 73(Supplement 1):S74–S76

Aznar M, Espinosa-Pereiro J, Saborit N et al (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tuberculosis management in Spain. Int J Infect Dis 108:300–305

Barrett J, Painter H, Rajgopal A et al (2021) Increase in disseminated TB during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 25(2):160–166

García-García J-M, Blanc F-X, Buonsenso D et al (2022) COVID-19 hampered diagnosis of TB infection in France, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom. Archivos de Bronconeumología

World Health Organization (2018) Latent tuberculosis infection: updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260233. Accessed 17 Aug 2022

Walker TM, Lalor MK, Broda A et al (2014) Assessment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission in Oxfordshire, UK, 2007–12, with whole pathogen genome sequences: an observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2(4):285–292

Shea KM, Kammerer JS, Winston CA et al (2014) Estimated rate of reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection in the United States, overall and by population subgroup. Am J Epidemiol 179(2):216–225

O’Connell J (2022) A quality of care evaluation to identify priorities for improving tuberculosis care in Ireland [Thesis]. https://repository.rcsi.com/articles/thesis/A_Quality_of_Care_Evaluation_to_Identify_Priorities_for_Improving_Tuberculosis_Care_in_Ireland/17000317. Accessed 17 Aug 2022

Collin SM, De Vries G, Lӧnnroth K et al (2018) Tuberculosis in the European Union and European Economic Area: a survey of national tuberculosis programmes. Eur Respir J 52(6)

Margineanu I, Rustage K, Noori T et al (2022) Country-specific approaches to latent tuberculosis screening targeting migrants in EU/EEA countries: a survey of national experts, September 2019 to February 2020. Eurosurveillance 27(12):2002070

Comhairle na nOspidéal (2000) Report of the committee on respiratory medicine and the management of tuberculosis, July 2000

Comhairle na nOspidéal (2003) Report of the committee to advance the implementation of the Comhairle report on respiratory medicine and the management of tuberculosis. http://hdl.handle.net/10147/46428. Accessed 17 Aug 2022

Eastern Region Health Authority Working Group (2004) Report of the Eastern Region Health Authority Working Group on tuberculosis services in the Eastern Region and respiratory services in the South Western area health board

O’Meara M (2007) An evaluation of TB service delivery in the Northern Area Health Board: thesis submitted as part requirement for the membership of the Faculty of Public Health Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland. https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/263892. Accessed 17 Aug 2022

O’Connell J, Reidy N, McNally C et al (2022) Delayed tuberculosis diagnosis in a low incidence country and its effect on cost of care. Open Forum Infect Dis 9(6):ofac164

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2021) Consumer price indices. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PRICES_CPI. Accessed 29 Nov 2021

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2021) Purchasing power parities for GDP and related indicators. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PPPGDP. Accessed 29 Nov 2021

Central Statistics Office (2018) Population and labour force projections 2017 - 2051. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-plfp/populationandlabourforceprojections2017-2051/populationprojectionsresults/. Accessed 8 Dec 2022

Health Protection Surveillance Centre. Annual reports on the epidemiology of tuberculosis in Ireland. https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/vaccinepreventable/tuberculosistb/tbdataandreports/annualreports/. Accessed 8 Dec 2022

Fox GJ, Barry SE, Britton WJ, Marks GB (2013) Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 41(1):140–156

Alsdurf H, Hill PC, Matteelli A et al (2016) The cascade of care in diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 16(11):1269–78

Diel R, Sotgiu G, Andres S et al (2020) Cost of multidrug resistant tuberculosis in Germany-an update. Int J Infect Dis

De Vries G, Baltussen R (2013) Kosten van tuberculose en TBC-bestrijding in Nederland [Cost of tuberculosis and tuberculosis control in the Netherlands]. Tegen Tuber 109:3–7

Department of Health (2009) Supply of TB drugs to patients – changes to regulations and advice on implementation. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Communicablediseases/Tuberculosis/DH_078136. Accessed 29 Nov 2020

Chan E, Nolan A, Denholm J (2017) How much does tuberculosis cost? An Australian healthcare perspective analysis. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 41(3):E191–E194

Marks SM, Flood J, Seaworth B et al (2014) Treatment practices, outcomes, and costs of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, United States, 2005–2007. Emerg Infect Dis 20(5):812

Diel R, Rutz S, Castell S, Schaberg T (2012) Tuberculosis: cost of illness in Germany. Eur Respir J 40(1):143–151

Central Statistics Office (2020) EHQ15: Average weekly, hourly earnings and weekly paid hour of all employees by economic sector 2 digit NACE rev 2, quarter and statistic. https://statbank.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=EHQ15&PLanguage=0. Accessed 12 Sep 2020

Central Statistics Office (2020) QLF02: ILO Participation and unemployment rates by sex, quarter and statistic. https://statbank.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/define.asp?MainTable=CDS08&ProductID=DB_PSER&PLanguage=0&Tabstrip=INFO&PXSId=0&SessID=17183702&FF=1&tfrequency=1. Accessed 12 Sep 2020

World Health Organization Health. Statistics and information systems metrics: disability-adjusted life years. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/metrics_daly/en/. Accessed 12 Sep 2022

Watkiss P, Steve P, Mike H (2005) Baseline scenarios for service contract for carrying out cost-benefit analysis of air quality related issues, in particular in the clean air for Europe (CAFE) programme. AEAT/ED51014/Baseline 5

Health information and quality authority (2015) Health technology assessment of a selective BCG vaccination programme. https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2017-01/BCG_technical_report.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2021

Subbaraman R, Jhaveri T, Nathavitharana RR (2020) Closing gaps in the tuberculosis care cascade: an action-oriented research agenda. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis 19:100144

Greenaway C, Pareek M, Abou Chakra C-N et al (2018) The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for latent tuberculosis among migrants in the EU/EEA: a systematic review. Eurosurveillance 23(14):17–00543

Houben RM, Lalli M, Sumner T et al (2016) TIME Impact-a new user-friendly tuberculosis (TB) model to inform TB policy decisions. BMC Med 14(1):1–10

O’Connell J, de Barra E, McConkey S (2022) Systematic review of latent tuberculosis infection research to inform programmatic management in Ireland. Irish J Med Sci 191(4):1485–1504

Charlesworth A (2014) Why is health care inflation greater than general inflation? J Health Serv Res Policy 19(3):129–130

Grant C, McHugh J, Ryan C et al (2022) Symptoms to script: delays in tuberculosis treatment in the west of Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 191(1):295–300

Golub J, Bur S, Cronin W et al (2006) Delayed tuberculosis diagnosis and tuberculosis transmission. J Tuberc Lung Dis 10(1):24–30

Committee on the Future of Healthcare (2017) Sláintecare Report. https://assets.gov.ie/22609/e68786c13e1b4d7daca89b495c506bb8.pdf. Accessed 26 Apr 2021

Menzies NA, Cohen T, Hill AN et al (2018) Prospects for tuberculosis elimination in the United States: results of a transmission dynamic model. Am J Epidemiology 187(9):2011–20

Hill A, Becerra J, Castro K (2012) Modelling tuberculosis trends in the USA. Epidemiol Infect 140(10):1862–1872

Health Protection Surveillance Centre (2019) Annual epidemiological report for tuberculosis. https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/vaccinepreventable/tuberculosistb/tbdataandreports/2019_Q1-4_TB_v1.0.pdf. Accessed 8 Aug 2021

Campbell JR, Dowdy D, Schwartzman K (2019) Treatment of latent infection to achieve tuberculosis elimination in low-incidence countries. PLoS Med 16(6):e1002824

Roycroft E, Fitzgibbon M, Kelly D et al (2021) The largest prison outbreak of TB in Western Europe investigated using whole-genome sequencing. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 25(6):491–497

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not sought for this analysis because it used secondary data available online.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Connell, J., McNally, C., Stanistreet, D. et al. Ending tuberculosis: the cost of missing the World Health Organization target in a low-incidence country. Ir J Med Sci 192, 1547–1553 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03150-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03150-3