Abstract

Background

In the year 2020, the coronavirus pandemic invaded the world. Since then, specialized companies began to compete, producing many vaccines. Coronavirus vaccines have different adverse events. Menstrual disorders have been noticed as a common complaint post-vaccination.

Aim

Our study fills an important gap by evaluating the relationship between coronavirus vaccines and menstrual disorders.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study between 20 September 2021, and 1 October 2021, using an online survey. The questionnaire consisted of 36 questions divided into 4 sections: demographics, COVID-19 exposure and vaccination, hormonal background, and details about the menstrual cycle. Sample t-test, ANOVA test, chi-square, and McNemar test were used in bivariate analysis.

Results

This study includes 505 Lebanese adult women vaccinated against COVID-19. After vaccination, the number of women having heavy bleeding or light bleeding increased (p = 0.02 and p < 0.001, respectively). The number of women having regular cycles decreased after taking the vaccine (p < 0.001). Irregularity in the cycle post-vaccination was associated with worse PMS symptoms (p = 0.036). Women using hormonal contraception method or using any hormonal therapy had higher menstrual irregularity rates (p = 0.002 and p = 0.043, respectively). Concerning vaccine adverse events, those who had headaches had a higher rate of irregularity (p = 0.041). Those having PCOS, osteoporosis, or blood coagulation disorders had higher irregularity rate (p < 0.001 and p = 0.005, respectively).

Conclusion

Vaccine adverse events may include specific menstrual irregularities. Moreover, some hormonal medications and diseases are associated with the alteration of the menstrual cycle. This study helps in predicting vaccines’ menstrual adverse events, especially in a specific population prone to menstrual disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Throughout history, epidemics and diseases such as plague, influenza, and smallpox have invaded many civilizations and wiped out millions of people. Edward Jenner presented a scientific invention that contributed to the development of a vaccine achieving the protection against smallpox, which subsequently led to the complete eradication of the smallpox virus in 1979 [1]. Scientific and medical progress has led to the invention of hundreds of vaccines that reduced the risk of many diseases and lowered their death rates.

In the year 2020, the coronavirus pandemic invaded the world from China as the original epicenter, causing horrific damage on various levels [2], in addition to claiming millions of lives around the world [3]. Since then, specialized companies began to compete, producing many vaccines with high rates of effectiveness, causing a significant fade of most of the negative consequences resulting from this pandemic. According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Pfizer-BioNTech was the first vaccine introduced into the global market with an effectiveness of up to 95% [4]. Many vaccines have also been released and became available for use. Among them is AstraZeneca, with an effectiveness of 76% [5], Sinopharm, with an effectiveness of 79% [6], and Sputnik V vaccine, with an effectiveness of 80% [7]. Despite the presence of some negative attitudes toward vaccination, these vaccines were widely spread [8].

It is worth noting that the coronavirus vaccines, as all other vaccines, have adverse events related to their use [9]. With the start of the vaccination campaigns globally, many adverse events began to appear, ranging from low burden, such as fever, fatigue, tiredness, chills, nausea [10], to life threatening, such as stroke [11]. As coronavirus vaccines are still relatively new to the market, further studies should be conducted focusing primarily on the effects of these vaccines on various disorders and physical problems.

Menstrual disorders have been noticed to be a common complaint post-vaccination [12,13,14,15]. This fact is unsurprising based on the similar effects of other vaccines [16]. For these reasons, our study fills an important gap by evaluating the relationship between coronavirus vaccines and menstrual disorders, thus helping and guiding producing companies to reduce the burden accompanied by vaccines as much as possible.

The primary objective of this study is to assess the self-declared menstrual irregularities following the use of the COVID-19 vaccines. A secondary objective would be to assess menstrual regularity and premenstrual symptoms associated factors.

Materials and methods

Setting, study design

This is a cross-sectional study conducted on Lebanese adult women vaccinated against COVID-19 between 20 September 2021, and 1 October 2021. An online questionnaire was generated using Google Forms and spread via social media platforms, applying the snowball method, in order to obtain a larger sample. A pilot study was inducted on 30 women before distributing the questionnaire. All participants assured that everything was clear.

Participants

Out of the 537 participants that filled the self-administered Arabic survey, 32 were excluded due to one of the following reasons: not residing in Lebanon, being postmenopausal, age less than 18 years old, or have not taken the COVID vaccine. The total response rate was 991.15%. Afterward, 505 participants that met the following inclusion criteria were eligible for the study: menstruating women, residing in Lebanon and having taken any of the COVID-19 vaccines. All participants were informed that their anonymity is preserved. Since we addressed a large population from different sociodemographic backgrounds, we made sure that all questions were clear by providing an explanation for the following terms: menstrual cycle, period, and irregular menstrual cycle.

Data source measures

The questionnaire consisted of 36 questions divided into 4 sections, taking an average of 15 min to fill. The survey sections were as follows: demographics (age, weight, height, place of residency, and marital status), COVID-19 exposure and vaccination (previous infection with COVID-19, vaccine name, and adverse events experienced after the vaccine), hormonal background, and details about the menstrual cycle.

The last two sections investigated thoroughly the participants’ reproductive health and menstrual patterns and thus included questions about: contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy, menstruation habits, PMS patterns, previous pregnancies, history of hysterectomy, and related medical conditions.

The survey contained 6 sets of comparative binary questions (before vaccine/after vaccine). These questions are intended to check for specific changes in participants’ menstrual cycle after the vaccine, such as menstrual cycle duration, heavy bleeding, light bleeding, and menorrhagia.

Ethical consideration

Sahel General Hospital Ethical Committee waived the need for approval because this was an observational study. The study respected participants’ anonymity and confidentiality and was conducted according to the research ethics guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki [17]. Participants’ consent was obtained from the first question of the questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

The collected data was entered in Microsoft Excel and was analyzed using the Statistical Package of the Social Sciences (SPSS) v.25. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics were conducted where continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Concerning the bivariate analysis, the independent was used to compare percentages before and after vaccination, and a multivariable logistic regression was conducted taking into account sociodemographic variables and vaccination as a major independent variable to assess the odds of menstrual irregularities variables as major dependent variables.

Results

This study includes 505 premenopausal women vaccinated against COVID-19. We received complete responses for each section, as participants were not able to submit the survey without completing all of the parts. Participants were distributed to all governments. The majority were not married (68.7%), and the average age of participants was 26.9 years (ranging from 18 to 55 years). Most of the participants received the Pfizer vaccine (81.2%), followed by AstraZeneca (11.9%). A total of 84.4% of our sample had a second dose of the vaccine, 79.6% were not previously pregnant, and 99% were not breastfeeding (Table 1).

The majority of respondents did not use anti-pregnancy hormone therapy (89.1%) nor any hormonal therapy (93.7%). Around two-thirds had no change in menstruation after taking the vaccine. Regarding vaccine adverse events, 77.6% experienced pain near the vaccine injection location, 65.7% had fatigue, 42.6% had a headache, 7.7% had vomiting or diarrhea, and 6.1% had easy brushing. Overall, 90.5% experienced at least one adverse event of vaccination. A total of 5.5% of the participants have previously been diagnosed with heavy menstrual bleeding, 12.9% have previously been diagnosed with PCOS, 0.4% had osteoporosis, 0.4% had coagulation disorders, and 1% was previously diagnosed with endometriosis (Table 2).

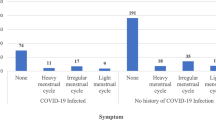

Heavy menstrual bleeding was decreased after vaccination, where the number of women having heavy bleeding decreased by 6% after vaccine (p = 0.003). Light menstrual bleeding was increased by 7% after vaccination (p < 0.001). In addition, regularity was affected by vaccination, where the number of women having regular cycles decreased after taking the vaccine by 8% (p < 0.001). Concerning the duration, it shifted to less than 5 days or more than 7 days after vaccination (p = 0.001) (Table 3).

Among women having regular cycles after vaccination, the majority had similar PMS symptoms as those before vaccination, and only 12.43% of them had worse PMS symptoms. However, having irregular cycles post-vaccination was associated with a higher rate of worse PMS symptoms (21.35%). This shows that the irregularity in the cycle post-vaccination is significantly associated with worse PMS symptoms (p = 0.036) (Table 4).

Table 5 shows the association between sociodemographics, general gynecological health, vaccination, and post-vaccine adverse events with the menstrual cycle’s regularity and PMS.

Regarding cycle’s regularity, women using the hormonal contraception method or using any hormonal therapy had higher menstrual irregularity rates (around 35% in users vs 20% in nonusers; p = 0.002 and p = 0.043, respectively). Moreover, those who stated having changes in menstrual cycle after vaccination had a higher irregularity than those who did not (38.4% vs 13.62%; p = 0.000). Concerning vaccine adverse events, those who had headache had a higher rate of irregularity (24.65% vs 17.24%; p = 0.041). Regarding previous health issues, those having PCOS, osteoporosis, or blood coagulation disorders had a higher irregularity rate (36.92% vs 17.95%; p = 0.000, 100% vs 20.07%; p = 0.005, 100% vs 20.07%; p = 0.005, respectively).

Regarding PMS, having changes in menstrual cycle after vaccination is associated with worse PMS (40.57% vs 4.35%; p < 0.001). Moreover, those who experienced fatigue, vomiting with diarrhea, or easy bruising after vaccination had worse PMS (18.37% vs 6.35%; p = 0.01, 28.2% vs 13.09%; p = 0.003, and 29.03% vs 13.29%; p = 0.01, respectively). Furthermore, those who did not experience any adverse event after the vaccine had better PMS (6.25% vs 3.93; p = 0.016). Concerning women that were previously diagnosed with heavy menstrual bleeding, they significantly had worse or better PMS (21.42% vs 13.83% and 17.85% vs 3.35%, respectively; p = 0.000). Women previously diagnosed with osteoporosis had worse PMS (100% vs 13.91%; p = 0.002), while those previously diagnosed with endometriosis had better PMS (40% vs 3.8%; p < 0.001).

Multivariable analysis

None of the sociodemographic characteristics or other independent variables were significantly associated with menstrual irregularities variables, except for the use of hormonal therapy (p = 0.002). None of the vaccines was significantly associated with menstrual irregularities.

Discussion

Several studies revealed that COVID-19 vaccines may have several adverse events. Whatever the vaccine type (mRNA, Vector, etc.), a considerable number of recipients affirmed experiencing local and/or systemic adverse events after receiving either dose of the vaccine [18, 19]. Some of these adverse effects were related to menstruation. Our study focused on menstrual disturbances post-vaccination, showing that 27% affirmed having changes in the menstrual cycle after vaccination. Similar findings were seen in other countries (i.e., the UK) but were not sufficient to confirm a firm relation between the menstrual changes and vaccination [15].

Going further into the details, the responders were interrogated about their menstrual disorders before and after taking the COVID-19 vaccine. Around a third of the participants (33%) declared having heavy bleeding after the vaccine, being less than those who had this problem before the vaccine (39%) (p-value = 0.003). However, heaving heavier periods after vaccination was noticed in other studies [20]. On the other hand, a smaller number of the participants affirmed having light bleeding (33.5%) post-vaccination, while 26.7% had light bleeding before the vaccine (p-value < 0.001). This decrease in the number of participants experiencing light bleeding following the vaccine was also reported in a study characterizing post-vaccine menstrual bleeding changes [21]. These bleeding irregularities may raise concerns for women who are willing to get vaccinated or to get another vaccine dose, especially since there are reports about the induction of thrombotic thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) by some vaccines [22]. Nevertheless, the experts emphasize that the risk of developing COVID-19 disease outweighs the risk of the less likely undesired vaccine effects, including TTS [22], in a way that even patients with bleeding disorders are advised to get the vaccine [23].

Moreover, 12.5% of participants experienced irregular cycles before the vaccine; this number increased to 20.4% after the vaccine (p-value < 0.001), supporting another study regarding this concern [24]. One possible explanation for this irregularity is the psychological stress perceived by the woman before, during, and/or after receiving the vaccine, as higher stress levels were associated with menstrual irregularity. However, these stress levels were not associated with menstrual bleeding changes [25], which renders this possibility less likely.

Additionally, our study found that irregular cycles were associated with worse PMS symptoms. The physiopathological mechanism of PMS can be explained by the endocrine system alterations [26], which may be caused by the cycle irregularity. The heavy bleeding experienced by many participants can also be a contributor to a worse PMS [27].

Concerning cycle regularity, several factors were noticed to influence the menstrual cycle. The use of hormonal contraception in some of the participants was associated with higher rates of menstrual irregularity, which backs up other studies regarding the effects of contraception on the cycle [28]. Similar effects were also seen with the use of any hormonal treatment, which may be explained by the fact that these treatments interfere with the normal physiological hormonal sequences, especially the hormonal physiology of ovulation [29]. Additionally, participants who experienced post-vaccine headaches had higher cycle irregularity rates. A more defined relation between this type of headache and menstrual abnormalities should be established, possibly mimicking the association between chronic migraine and menstruation disorders [30]. Moreover, higher rates of irregular cycles were also seen in patients with PCOS, osteoporosis, and/or blood coagulation disorders, which was previously described in other studies [31,32,33].

Furthermore, numerous variables were seen to impact the PMS intensity. Participants who experienced fatigue, vomiting, diarrhea, and/or easy bruising post-vaccine were associated with having worse PMS. It is not rare for these signs to be seen before/during menstruation [34]; however, the fact that they seem to be worse after the vaccination is worth mentioning. Likewise, women who were previously diagnosed with osteoporosis before the vaccine also experienced a worse PMS. The vaccine might have an aggravating effect on the already described severe PMS in osteoporosis patients [35]. Additionally, participants who were previously diagnosed with endometriosis had better PMS. This might be explained by the retrograde migration of the endometrial tissue towards the ovaries in the case of endometriosis [36], thus affecting its secretion of progesterone, which, in turn, is responsible for the severity of PMS symptoms [37].

Limitations

This study had several limitations, mainly concerning the targeted population. Postmenopausal women were excluded from this study, eliminating the ability to correlate vaccination to post-menopausal gynecological adverse events. Additionally, this study was done soon after the vaccine had reached Lebanon (around 20% got two shots [38]); the priority of vaccination was for those being at risk of developing COVID-19 complications, thus increasing the proportion of participants with comorbidities, possibly affecting our study’s outcome. This might cause a confounding bias. In addition, this study had a low number of participants diagnosed with certain diseases expected to affect the menstrual cycle, such as osteoporosis, blood coagulation disorders, and endometriosis, lowering the value of results obtained. This may have contributed to the low power of the sample, hampering significant results in the multivariable analysis. Finally, our sample was not homogeneous in terms of residency location and type of vaccine received, disrespecting the exact proportions.

Conclusion

Our findings support the fact that the COVID vaccine has effects on the menstrual cycle, explaining the findings reported by many women post-vaccination. Moreover, it shows that some diseases are associated with the alteration of the menstrual cycle. This helps in predicting vaccines’ menstrual adverse events, especially in a specific population with a higher risk. Our study highlights the need for more studies on the management of menstrual irregularities, leading to clear guidelines for managing the cases.

Data availability

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Greenwood B (2014) The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369:20130433. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0433

Kaye AD, Okeagu CN, Pham AD et al (2021) Economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare facilities and systems: international perspectives. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 35:293–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2020.11.009

COVID Live - Coronavirus Statistics - Worldometer. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed 11 Jan 2022

Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine overview and safety | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/Pfizer-BioNTech.html. Accessed 11 Jan 2022

The Oxford/AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1-S [recombinant] vaccine) COVID-19 vaccine: what you need to know. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-oxford-astrazeneca-covid-19-vaccine-what-you-need-to-know. Accessed 11 Jan 2022

The Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine: what you need to know. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-sinopharm-covid-19-vaccine-what-you-need-to-know. Accessed 11 Jan 2022

Russia says Sputnik COVID-19 vaccine shows better efficacy than MRNA vaccines - Health Policy Watch. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/russia-sputnik-v-vaccine-effective-mrna/. Accessed 11 Jan 2022

Jabbour D, Masri JE, Nawfal R et al (2022) Social media medical misinformation: impact on mental health and vaccination decision among university students. Ir J Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-02936-9

Vaccine side effects and adverse events | History of Vaccines. https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/articles/vaccine-side-effects-and-adverse-events. Accessed 11 Jan 2022

Possible side effects after getting a COVID-19 vaccine | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/expect/after.html. Accessed 11 Jan 2022

Hidayat R, Diafiri D, Zairinal RA et al (2021) Acute ischaemic stroke incidence after coronavirus vaccine in Indonesia: case series. Curr Neurovasc Res 18:360–363. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202618666210927095613

Coronavirus vaccine - weekly summary of Yellow Card reporting. In: GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-adverse-reactions/coronavirus-vaccine-summary-of-yellow-card-reporting. Accessed 23 Mar 2022

Laganà AS, Veronesi G, Ghezzi F et al (2022) Evaluation of menstrual irregularities after COVID-19 vaccination: results of the MECOVAC survey. Open Med (Wars) 17:475–484. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2022-0452

Muhaidat N, Alshrouf MA, Azzam MI et al (2022) Menstrual symptoms after COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional investigation in the MENA region. Int J Womens Health 14:395–404. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S352167

Male V (2021) Menstrual changes after COVID-19 vaccination. BMJ 374:n2211. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2211

Suzuki S, Hosono A (2018) No association between HPV vaccine and reported post-vaccination symptoms in Japanese young women: results of the Nagoya study. Papillomavirus Res 5:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2018.02.002

World Medical Association (2001) World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ 79:373–374

Anand P, Stahel VP (2021) Review the safety of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: a review. Patient Saf Surg 15:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-021-00291-9

Menni C, Klaser K, May A et al (2021) Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 21:939–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00224-3

Published Menstrual changes following COVID-19 vaccination. In: Norwegian Institute of Public Health. https://www.fhi.no/en/news/2021/menstrual-changes-following-covid-19-vaccination/. Accessed 30 Dec 2021

Lee KM, Junkins EJ, Fatima UA et al (2021) Characterizing menstrual bleeding changes occurring after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

Islam A, Bashir MS, Joyce K et al (2021) An update on COVID-19 vaccine induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia syndrome and some management recommendations. Molecules 26:5004. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26165004

EAHAD co-signs COVID-19 vaccination guidance – EAHAD. https://eahad.org/covid-19-vaccination-guidance-for-people-with-bleeding-disorders/. Accessed 1 Jan 2022

Male V (2021) Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on menstrual periods in a retrospectively recruited cohort

Nagma S, Kapoor G, Bharti R et al (2015) To evaluate the effect of perceived stress on menstrual function. J Clin Diagn Res 9:QC01–03. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/6906.5611

da Silva CML, Gigante DP, Carret MLV, Fassa AG (2006) Population study of premenstrual syndrome. Rev Saude Publica 40:47–56. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102006000100009

Yamamoto K, Okazaki A, Sakamoto Y, Funatsu M (2009) The relationship between premenstrual symptoms, menstrual pain, irregular menstrual cycles, and psychosocial stress among Japanese college students. J Physiol Anthropol 28:129–136. https://doi.org/10.2114/jpa2.28.129

Stubblefield PG (1994) Menstrual impact of contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 170:1513–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(94)05013-1

Venturoli S, Porcu E, Fabbri R et al (1986) Menstrual irregularities in adolescents: hormonal pattern and ovarian morphology. Horm Res 24:269–279. https://doi.org/10.1159/000180567

Spierings ELH, Padamsee A (2015) Menstrual-cycle and menstruation disorders in episodic vs chronic migraine: an exploratory study. Pain Med 16:1426–1432. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12788

Escobar-Morreale HF (2018) Polycystic ovary syndrome: definition, aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 14:270–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2018.24

Kalyan S, Prior JC (2010) Bone changes and fracture related to menstrual cycles and ovulation. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 20:213–233. https://doi.org/10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v20.i3.30

Deligeoroglou E, Karountzos V (2018) Abnormal uterine bleeding including coagulopathies and other menstrual disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 48:51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.08.016

Bernstein MT, Graff LA, Avery L et al (2014) Gastrointestinal symptoms before and during menses in healthy women. BMC Womens Health 14:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-14

Lee SJ, Kanis JA (1994) An association between osteoporosis and premenstrual symptoms and postmenopausal symptoms. Bone Miner 24:127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-6009(08)80150-x

Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C et al (2019) Endometriosis. Endocr Rev 40:1048–1079. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2018-00242

Rapkin AJ, Akopians AL (2012) Pathophysiology of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Menopause Int 18:52–59. https://doi.org/10.1258/mi.2012.012014

covidvax.live: Live COVID-19 Vaccination Tracker - See vaccinations in real time! http://covidvax.live/location/lbn. Accessed 23 Mar 2022

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: OI, AD, and JEM; data curation: OI; formal analysis: JEM and BZ; funding acquisition: no funding; methodology: AD, JEM, and LME; supervision: PS; roles/writing-original draft: AD, JEM, LME, and BZ; writing-review and editing: JEM, AD, and PS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dabbousi, A.A., El Masri, J., El Ayoubi, L.M. et al. Menstrual abnormalities post-COVID vaccination: a cross-sectional study on adult Lebanese women. Ir J Med Sci 192, 1163–1170 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03089-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03089-5