Abstract

Background

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic caused severe disruption to scheduled surgery in Ireland but its impact on emergency abdominal surgery (EAS) is unknown.

Aims

The primary objective was to identify changes in volume, length of stay (LOS), and survival outcomes following EAS during the pandemic. A secondary objective was to evaluate differences in EAS patient flow including admission source, ITU utilisation, discharge destination, and readmission rates.

Methods

Using a national administrative dataset, demographic, comorbidity, and patient flow data on 5611 patients admitted for EAS between 2018 and 2020 were extracted. Pre-pandemic and pandemic timeframes were compared using graphic and regression analyses, and bivariate logistic regression, adjusting for demographics and case-mix.

Results

There was a 19.9% decrease in EAS during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic with no difference in comorbidity, nor in the commonest procedures. Most patients (92.4%) were admitted from home. In-hospital post-operative mortality was unchanged (7.6%). Patients over 80 comprised 16.3% of EAS pre-COVID, but 17.9% during COVID. Average total LOS reduced significantly by 4.9 days and 3.5 days during COVID-19 waves 1 (29 Feb 2020–30 June 2020) and 2 (1 July 2020–30 Nov 2020), respectively. During wave 1, pre-operative LOS reduced (1 day) and ICU LOS was significantly shorter (0.8 days), but similar change was not observed during wave 2.

Conclusions

Significant improvements in patient flow following admission for EAS during the pandemic were observed. These changes were not associated with greater mortality nor increased readmission rates and offer important insights into optimal delivery of EAS services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Emergency abdominal surgery (EAS), performed for a range of acute gastrointestinal conditions, is associated with an in-hospital mortality of 7.7%, a prolonged length of stay in hospital, and a combined risk of death or discharge to a nursing home of 50% for people over 80 [1, 2]. National policy has long recommended separation of scheduled and unscheduled surgery in an effort to improve outcomes and patient flow [3], but implementation has proven challenging. The urgent service redesign necessitated by the pandemic resulted in a public health system that exclusively prioritised emergency surgery [4]. The resulting changes offer an opportunity to deepen our understanding of factors relevant to provision of EAS in Ireland.

Globally, it is estimated that 28.4 million scheduled operations were deferred during the first 12 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic [5]. Like elsewhere, Irish hospitals were instructed to cancel scheduled surgery to create capacity for the anticipated surge in SARS-CoV-2 patient admissions [6]. It was anticipated that emergency surgery, usually necessitated by an acute threat to life or well-being that requires prompt treatment, would be impacted to a smaller extent [7]. The onset of the pandemic was marked by concern about the safety of surgery for patients and staff alike with a range of factors discouraging patients from seeking medical care [8,9,10,11,12,13]. As a result, admissions for emergency general surgery reduced in Europe and elsewhere [8,9,10,11,12, 14, 15]. In Ireland, a model 3 hospital reported a 27% reduction in the number of ED admissions requiring surgical intervention during the pandemic but the national impact remains unknown [16].

The aim of this study is to characterise the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on EAS using the National Quality Assurance and Improvement System (NQAIS) national administrative database. The primary objective was to identify any changes in the volume of cases, hospital and ICU length of stay (LOS), and survival outcomes following EAS. A secondary objective was to evaluate patient flow among patients undergoing EAS during the pandemic, including admission source, discharge destination, and readmission rates.

Methods

Context

The Health Service Executive (HSE) is the publicly funded healthcare system that provides health services to the 4.9 million residents of the Republic of Ireland. Hospitals are categorised into one of four ‘models’ (model 1, 2, 3, or 4) based on functionality and complexity of care provided. Model 3 hospitals admit undifferentiated acute medical and surgical patients and have facilities such as an emergency department (ED) and intensive care unit (ICU). In addition to these services, model 4 hospitals accept tertiary referrals from other hospitals and provide a higher level of intensive care [17]. All acute hospitals in Ireland are assigned to one of seven hospital groups.

Twenty-nine emergency departments are provided by twenty-eight hospital sites in Ireland, while twenty-four Irish hospitals provide acute surgical services. Those attending a hospital’s out-patient department or ED may be charged a standard fee of €100, except for certain pre-defined groups such as medical card holders, those receiving treatment for COVID-19, or those referred to ED by their general practitioner (GP) [18]. Medical cards are issued to certain individuals who have long-term illnesses or those whose income is below a set threshold. Medical card holders are exempt from hospital charges [18].

Data and analysis

We obtained data for all twenty-four acute public hospitals from the NQAIS. The NQAIS allows access to and analysis of Hospital In-Patient Enquiry (HIPE) data. HIPE is the national database of patient discharge data collected from all acute public hospitals in the Republic of Ireland [19]. The database is compiled from medical records and coded by expert clinical coders on behalf of the HSE Healthcare Pricing Office [19]. This data is coded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification, Australian Classification of Health Interventions, Australian Coding Standards, 8th Edition [19].

Hospital admission data coded with EAS as the primary procedure was obtained from the NQAIS for the years 2018 to 2020. The data extraction was updated from a previously reported EAS dataset [2]. In this study, we used data, based on date of admission, from 1 January 2018 to 28 February 2020 as the pre-pandemic control group. We defined the COVID-19 pandemic period as the period from 29 February, date the first case of COVID-19 was reported in the Republic of Ireland, to 31 November 2020. We divided the pre-COVID-19 and the COVID-19 periods into weekly periods, including weeks 10–48 of 2018 and 2019 as the pre-COVID-19 pandemic control group and weeks 10–48 of 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic study group. Weeks 48 to 52 were excluded to avoid variability observed due to a known ‘Christmas effect’ on surgical admissions during this time. We further split the COVID-19 period to represent the so-called wave 1 (29 February 2020–30 June 2020) and wave 2 (1 July 2020–30 November 2020) of the COVID-19 outbreak in Ireland. Total data for the 12 months of 2018 and 2019 and the weeks 1 to 48 of 2020 are included but the analysis comparing the COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 periods compares only admissions during weeks 10 to 48 in 2020 to admissions from the same weeks in 2018 and 2019 to avoid any distortion from weekly or seasonal variability that is observed in the dataset.

Data collected for each episode included age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status score, primary procedure code, primary and secondary diagnoses, dates of admission, discharge and primary procedure, hospital name, admission type and source, discharge destination, length of stay, and readmission after 7 and 30 days.

Graphical analyses were generated to show weekly variations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis to compare length of stay measures (total length of stay, pre-operative length of stay, post-operative length of stay, and ICU length of stay) and logistic regression analysis to compare outcome indicators (discharge destination, readmissions). All regression analyses were adjusted for patient case-mix.

To test differences in patient characteristics between the pre-pandemic and pandemic period, we used bivariate logistic regression for the available variables (sex, age group, admission source, ASA score, and CCI score).

This national, population-based study is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [20].

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 summarises the key EAS patient characteristics and outcomes. During the overall study period of 2018, 2019, and weeks 10 to 48 in 2020, there were 5611 admissions for emergency abdominal surgery to Irish public hospitals.

The total number of admissions remained stable during 2018 and 2019, with a noticeable reduction during the COVID-19 period. The pre-COVID-19 period (pre-COVID) had an average of 1527 EAS procedures while the COVID-19 (COVID) period had only 1223 such procedures. This represents a 19.9% decrease (304 cases) in EAS during the pandemic when compared to pre-COVID. Approaching the end of wave 1, the number of weekly admissions for EAS recovers slowly but drops sharply again with the onset of wave 2 (Fig. 1).

Overall, a slight majority of patients were female (50.7%, 53.3%, and 50.6% in 2018, 2019, and 2020, respectively) and 16.8% were over 80 years of age. Most patients (92.4%) were admitted directly from home and 7.6% died in hospital. The 70–79-year-old age group remained the largest cohort of emergency abdominal surgery patients, comprising 23.5% of all EAS admissions during the study period. The percentage of EAS patients over 80 increased from 16.3% pre-COVID to 17.9% during COVID (Table 1).

Around half (48.8%) of patients throughout the study period had an ASA physical status score of 3 or more with no difference between periods. Similarly, no difference was observed for CCI scores. One-fifth (22.3%) of patients during the COVID period had a 10 + CCI score.

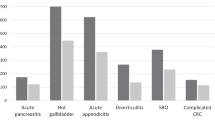

The 15 most commonly performed EAS procedures in each time period are specified in Table 2.

Length of stay and discharge

The average total length of stay (avLOS) for patients undergoing EAS reduced significantly from 23.4 days pre-COVID to 19.9 days during COVID. Variation in in-patient avLOS throughout the study period is illustrated graphically in Fig. 2. The average post-operative length of stay (post-op avLOS) pre-COVID was 18.3 days and decreased to 15.7 days during COVID. There was a non-significant reduction in average length of ICU stay, with an average of 2.9 ICU bed days per patient pre-COVID dropping to 2.5 ICU bed days during the COVID period (Table 1).

A higher proportion of EAS admissions were discharged home during the pandemic. 74.7% of patients were discharged home pre-COVID, increasing to 78.8% during the COVID period. This corresponded to a decrease in the proportion of patients discharged to a nursing home, which fell to 6.9% for the COVID period compared to an average of 12.6% for the pre-COVID period.

Regression analysis

The regression analyses compare weeks 10 to 48 in each of years 2018, 2019, and 2020, including 1600, 1454, and 1223 EAS admissions, respectively. Table 3 summarises the OLS regression estimates for all length of stay measures. Relative to the pre-COVID period, we found a statistically significant reduction in the average total length of stay (avLOS) by 4.9 days during wave 1 and by 3.5 days during wave 2 in the COVID period. There was a statistically significant decrease in the average pre-operative length of stay by 1 day during wave 1, but during wave 2, no significant change was observed. The average post-operative length of stay (post-op avLOS) was reduced significantly by 3.8 days in wave 1, and by 2.8 days during wave 2. In wave 1, the ICU length of stay was significantly shorter by 0.8 days; however, no significant changes were observed in wave 2.

Table 4 summarises the logistic regression estimates for the discharges (home and deaths) and readmissions (7 days post-surgery and 30 days post-surgery). Relative to the pre-COVID period, significantly more patients were discharged home during wave 1 (OR: 1.47, p = 0.007) and even more during wave 2 (OR: 1.6, p < 0.001). However, no statistically significant effects were found in terms of patient mortality, although the numbers indicate a slight, insignificant reduction during waves 1 and 2. Similarly, we observe no important difference in readmission rate at 7 and 30 days, although the numbers may indicate a slight reduction.

The bivariate logistic regression indicated significantly fewer women in the population during the COVID period (49.4% vs 52.8%, OR 0.87, p = 0.043) and more patients aged older than 80 years (18.2% vs 16.0%, OR 1.40, p = 0.041). This was confirmed in the multivariate logistic regression where the statistical significance for OR for women and age over 80 were stronger (OR 0.85, p = 0.020; OR 1.54, p = 0.015). No other variables showed statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the bivariate or multivariate analysis.

Discussion

This national analysis of EAS in Irish public hospitals establishes a 19.9% decrease in EAS procedures performed during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic period. We observed a change in patient demographics with a statistically significant decrease in the number of women and an increase in those aged 80 + undergoing EAS during the pandemic. When compared to the pre-pandemic control group, patients during wave 1 of the pandemic were significantly more likely to be discharged home (vs other discharge destinations, OR: 1.47, p = 0.007), had a significantly shorter overall length of stay (4.88 days shorter, p < 0.001), underwent surgery on average one day sooner (1.06 days earlier, p = 0.021), had a shorter ICU stay (0.8 days shorter, p = 0.015), and were discharged home nearly 4 days earlier after surgery (3.81 days earlier, p < 0.001). During wave 2 of the pandemic, patients were significantly more likely to be discharged home (vs other discharge destinations, OR: 1.60, p < 0.001), had a significantly shorter overall length of stay (3.47 days shorter, p = 0.002), and were discharged nearly three days earlier after surgery (2.78 days earlier, p = 0.006). We found a reduction in avLOS, pre-operative LOS, and post-operative LOS during the pandemic. There was also a reduction in ICU LOS when compared to previous years. The finding of reduced avLOS was not associated with any statistically significant change in 7-day and 30-day readmission rates in our study population. We also observed a slight reduction in in-hospital mortality among patients undergoing EAS during the pandemic but this result was also not statistically significant and may be explained by changes in patient demographics and case-mix.

Other studies of emergency surgical services during the pandemic, including the UK NELA interim COVID-19 report [21], identify similar decreases in EAS admissions [8,9,10,11,12, 14, 15]. A nationwide analysis in France reported a 20.9% decrease in emergency surgery [12]. Reichert et al. surveyed 98 collaborators from thirty-one countries with 87% of respondents reporting a decrease in the number of patients undergoing emergency surgery [11]. Reasons for this reduction in EAS could include patients avoiding healthcare facilities due to the risk of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection [10, 12, 13], people being encouraged to stay at home [9, 13], GPs favouring conservative measures instead of referring patients to ED [10, 12], and possibly a more refined understanding of what constitutes a surgical ‘emergency’. It is noteworthy that reductions happened during both waves, making it less likely that fear of the initially unknown impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on surgical outcomes [22] or shortages of personal protective equipment were key factors. A limitation of any national administrative dataset is that hospital coding systems may not function optimally during a pandemic due to staff redeployment. Nonetheless, the 20% reduction identified in Ireland is remarkably consistent with observations from other health systems making this less likely [10, 12].

There are gaps in our understanding of the fate of individuals considered for, but not ultimately undergoing, emergency surgery. Greater availability of senior surgical decision-makers [3] due to the exceptional cancellation of all scheduled surgery may have contributed to better decisions and fewer futile interventions being undertaken. The ongoing ELF-2 study will increase understanding of this cohort of patients by clarifying the denominator from which EAS patients are drawn [23]. We have no data to evaluate whether morbidity or mortality have occurred in the community due to unmet needs for emergency surgery and are unaware of even anecdotal evidence suggesting this. The possibility that operations coded as EAS in non-pandemic times may include a subset of patients undergoing urgent procedures classified as an emergency in order to secure a scarce hospital bed or theatre slot is sometimes proposed. It is noteworthy that in this national dataset, there is little difference in the rank order of the 15 most commonly performed procedures suggesting consistency in the types of procedures classified as an emergency irrespective of the pandemic.

Despite many challenges in care delivery, we observed no evidence of inferior in-hospital outcomes following EAS during 2020, nor of rationing of care based on age alone. Lazzati et al. noted that patients seeking care during the pandemic presented later, and more severely ill, than expected [12]. In contrast, our study found that 22.3% of EAS patients during the pandemic had a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of more than 10, not dissimilar to that normally observed. The unchanged post-operative mortality rate observed in Ireland during the pandemic contrasts with the higher rate of mortality following EAS reported by Surek et al., although we note that 6% of patients in that series likely underwent surgery while infected with SARS-CoV-2, a recognised risk factor for poorer outcomes [14, 21]. The UK National Emergency Laparotomy Audit reported a 7.2% 30-day mortality for COVID-19-negative emergency bowel surgery patients in England and Wales during the pandemic [21]. Shorter pre-operative and post-operative LOS during the pandemic may favourably influence outcomes by avoidance of prolonged bed rest [24] and reduced pre-operative sepsis. Readmission rates were similar to prior to the pandemic.

The changes in patient flow observed during the pandemic are noteworthy and show that the prolonged LOS observed after EAS in Ireland is amenable to intervention. There was a noticeable reduction in the proportion of patients discharged to a nursing home (an average of 12.6% for the pre-COVID period vs 6.9% during the COVID period). The media coverage of COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes, greater restrictions on visitation, and stricter admission policies may each have contributed to this change. At the same time, the lockdown and resulting shift towards working from home may have fostered a domestic environment that, despite some adverse impacts, is more conductive to care of elderly family members at home. Previous work suggests that in Ireland, discharge to a nursing home is associated with prolongation of LOS [1]. There was significant investment to maximise nursing home access at the beginning of the pandemic to create hospital capacity, and is likely to be a key factor in the observed improvement. The hazards of prolonged hospitalisation were more obvious to patients and staff during the pandemic and favoured earlier discharge. Overall, LOS following EAS in Ireland remains considerably longer than in the UK where a 14.1 day average length of stay is reported [21]. Similarly, pre-operative LOS before EAS in Ireland is longer than in the UK and while it reduced by 1 day in wave 1, this reduction was not sustained in wave 2 [2, 21, 25]. Our finding of a shorter LOS with no increase in readmission rates contrasts with that of Kaboli et al. [26], whose pre-COVID study found that a LOS longer or shorter than average is associated with increased readmission rates.

The strength of this study is the analysis of a complete national EAS database over a 3-year period, including data for more than one surge (‘wave’) in COVID-19 infection. Other studies are limited to one ‘wave’ of COVID-19, fewer variables, to selected hospitals or regions and may not be generalisable to national populations. The HIPE dataset represents the most comprehensive resource on EAS in the Republic of Ireland. The limitations of this study arise due to its dependence on the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the HIPE dataset. Data is manually added to this dataset by trained clinical coders; this may have been impacted by the pandemic. As with all manual transfers of data from one source to another, errors in this dataset are inevitable and cannot be completely eliminated. Certain additional metrics like mortality rates after discharge would be valuable but the absence of a unique patient identifier in the Republic of Ireland is a barrier.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study has shown that the pandemic has acted as a catalyst for significant improvements in patient flow for people undergoing EAS within Irish public hospitals. Better understanding of the system changes responsible for these improvements will enable continued progress in the important public health goal of delivering a high-quality, safe, and efficient EAS service nationally.

Availability of data and material

HIPE (Hospital In-Patient Enquiry) data applied in this study are available from the NQAIS but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Code availability

Software application: Stata v16. Data used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request subject to permission from the NQAIS.

References

McCann A, Sorensen J, Nally D et al (2020) Discharge outcomes among elderly patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery: registry study of discharge data from Irish public hospitals. BMC Geriatr 20(1):72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1469-4

Nally DM, Sorensen J, Valentelyte G et al (2019) Volume and in-hospital mortality after emergency abdominal surgery: a national population-based study. BMJ Open 9(11):e032183. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032183

National Clinical Programme in Surgery (2013) Model of care for acute surgery. Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Ireland

McNamara DA (2020) Creating a COVID-resilient future for surgery. Br J Surg 107(10):e360. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11791

COVIDSurg Collaborative, (2020) Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg 107(11):1440–1449. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11746

Kane C, McGrath P, Bowers F (2020) Hospitals move to cancel appointments, elective surgery. RTE News. https://www.rte.ie/news/2020/0316/1123584-hospitals-move-to-cancel-appointments-elective-surgery/. Accessed 24 Nov 2021

Spinelli A, Pellino G (2020) COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives on an unfolding crisis. Br J Surg 107(7):785–787. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11627

Castoldi L, Solbiati M, Costantino G et al (2021) Variations in volume of emergency surgeries and emergency department access at a third level hospital in Milan, Lombardy, during the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Emerg Med 21(1):59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-021-00445-z

Patriti A, Eugeni E, Guerra F (2020) What happened to surgical emergencies in the era of COVID-19 outbreak? Considerations of surgeons working in an Italian COVID-19 red zone. Updates Surg 72(2):309–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-020-00779-6

Pikoulis E, Koliakos N, Papaconstantinou D et al (2021) The effect of the COVID pandemic lockdown measures on surgical emergencies: experience and lessons learned from a Greek tertiary hospital. World J Emerg Surg 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-021-00364-1

Reichert M, Sartelli M, Weigand MA et al (2020) Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on emergency surgery services-a multi-national survey among WSES members. World J Emerg Surg 15(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-020-00341-0

Lazzati A, Raphael Rousseau M, Bartier S et al (2021) Impact of COVID-19 on surgical emergencies: nationwide analysis. BJS Open 5 (3). https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zrab039

Ponkilainen V, Kuitunen I, Hevonkorpi TP et al (2020) The effect of nationwide lockdown and societal restrictions due to COVID-19 on emergency and urgent surgeries. Br J Surg 107(10):e405–e406. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11847

Surek A, Ferahman S, Gemici E et al (2021) Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on general surgical emergencies: are some emergencies really urgent? Level 1 trauma center experience. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 47(3):647–652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01534-7

de Mestral C, Gomez D, Sue-Chue-Lam C et al (2021) Variable impact of COVID-19 on urgent intervention in Ontario. Br J Surg. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znab121

Rohan P, Slattery F, Nason GJ et al (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on surgical activity. Ir Med J 113(10):202

Mealy K, Keane F, Kelly P et al (2017) What is the future for general surgery in model 3 hospitals? Ir J Med Sci 186(1):225–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1545-0

Health Service Executive (2021) Hospital Charges. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/acute-hospitals-division/patient-care/hospital-charges/. Accessed 1 Jul 2021

Health Information and Quality Authority (2021) Hospital In-Patient Enquiry (HIPE). https://www.hiqa.ie/areas-we-work/health-information/data-collections/hospital-patient-enquiry-hipe. Accessed 1 Jul 2021

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M et al (2014) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 12(12):1495–1499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013

NELA Project Team (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on emergency laparotomy – an interim report of the national emergency laparotomy audit, 23 March 2020 – 30 September 2020. United Kingdom

Aminian A, Safari S, Razeghian-Jahromi A et al (2020) COVID-19 outbreak and surgical practice: unexpected fatality in perioperative period. Ann Surg 272(1):e27–e29. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003925

Reeves N, Chandler S, McLennan E et al (2021) Defining the older patient population that require, but do not undergo emergency laparotomy: an observational cohort study protocol. Int J Clin Trials 8(2):138–144. https://doi.org/10.18203/2349-3259.ijct20210977

Walker J, Povey J, J L, (2018) Reducing the effects of immobility during hospital admissions. Nurs Times 114:18–20

COVIDSurg Collaborative (2020) Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet 396(10243):27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X

Kaboli PJ, Go JT, Hockenberry J et al (2012) Associations between reduced hospital length of stay and 30-day readmission rate and mortality: 14-year experience in 129 Veterans Affairs hospitals. Ann Intern Med 157(12):837–845. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00003

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Healthcare Pricing Office as the source of HIPE data, which is used in NQAIS Clinical. The authors would like to thank the Clinical Leads of the National Clinical Programmes (National Clinical Programme in Surgery), the NQAIS Clinical Steering Group, the HORC-NCP research group, and the Acute Hospital Division (HSE) for providing access to NQAIS Clinical.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors provided a substantial contribution to this project and were involved in conception, design, and execution of the work. JS and GV conducted the analyses. All authors interpreted the data. JR wrote the first draft of the manuscript and DMN, JS, and GV revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors commented on draft versions and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland (REC001534). The study was endorsed within the NQAIS Clinical Governance Framework. Data are presented in an anonymised fashion to ensure confidentiality.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of this manuscript and are aware of its submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rajesh, J., Valentelyte, G., McNamara, D.A. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on provision and outcomes of emergency abdominal surgery in Irish public hospitals. Ir J Med Sci 191, 2275–2282 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02857-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02857-z