Abstract

Extensions of dual definite subspaces to dual maximal definite ones are described. The obtained results are applied to the classification of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetries. The concepts of dual quasi maximal subspaces and quasi bases are introduced and studied. It is shown that complex shift \(g(\cdot )\rightarrow {g}(\cdot +ia)\) of Hermite functions \(g_n\) is an example of quasi bases in \(L_2({\mathbb {R}})\).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Let \(\mathfrak {H}\) be a Hilbert space with inner product \((\cdot ,\cdot )\) linear in the first argument and let J be a non-trivial fundamental symmetry, i.e., \(J=J^*\), \(J^2=I\), and \(J\not ={\pm \,{I}}\). The space \(\mathfrak {H}\) endowed with the indefinite inner product

is called a Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\).

A (closed) subspace \(\mathfrak {L}\) of the Hilbert space \(\mathfrak {H}\) is called nonnegative, positive, uniformly positive with respect to the indefinite inner product \([\cdot ,\cdot ]\) if, respectively, \([f,f]\ge {0}\), \([f,f]>0\), \([f,f]\ge {\alpha }\Vert f\Vert ^2, (\alpha >0)\) for all \(f\in \mathfrak {L}\!\setminus \!\{0\}\). Nonpositive, negative and uniformly negative subspaces are introduced similarly. In each of the above mentioned classes we can define maximal subspaces. For instance, a closed positive subspace \(\mathfrak {L}\) is called maximal positive if \(\mathfrak {L}\) is not a proper subspace of a positive subspace in \(\mathfrak {H}\). The concept of maximality for other classes of closed subspaces is defined similarly. A subspace \(\mathfrak {L}\) of \({{\mathfrak {H}}}\) is called definite if it is either positive or negative. The term uniformly definite is defined accordingly.

Subspaces \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) of \(\mathfrak {H}\) are called dual subspaces if \(\mathfrak {L}_-\) is nonpositive, \(\mathfrak {L}_+\) is nonnegative, and \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) are orthogonal with respect to \([\cdot , \cdot ]\), that is \([f_+, f_-]=0\) for all \(f_{+}\in \mathfrak {L}_+\) and all \(f_{-}\in \mathfrak {L}_-\).

The subject of the paper is dual definite subspaces. Our attention is mainly focused on dual definite subspaces \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) with additional assumption of the density of their direct sumFootnote 1

At first glance, the density of \(\mathcal {D}\) in \(\mathfrak {H}\) should imply the maximality of definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) in the Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\). This assumption is true when \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are uniformly definite. For the case of dual definite subspaces, Langer [13] constructed a densely defined sum (1.2) for which there exist various extensions to dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\):

The decomposition (1.2) is often appeared in the spectral theory of \({\mathcal {P}}{\mathcal {T}}\)-symmetric Hamiltonians [9] as the result of closure of linear spans of positive and negative eigenfunctions and it is closely related to the concept of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry in \({\mathcal {P}}{\mathcal {T}}\)-symmetric quantum mechanics (PTQM) [7, 8]. The description of symmetries \(\mathcal {C}\) is one of the key points in PTQM and it can be successfully implemented only in the case where the dual subspaces in (1.2) are maximal. This observation give rise to a natural question: how to describe all possible extensions of dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) to dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\)?

In Sect. 2 this problem is solved with the use of Krein’s results on non-densely defined Hermitian contractions [4, 11]. The main result (Theorem 2.6) reduces the description of extensions (1.3) to the solution of the operator equation (2.10).

Each direct sum \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\) of dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) generates an associated Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) defined in Sect. 3. If \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) are uniformly definite, then \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\) coincides with \(\mathfrak {H}\) and \(\mathfrak {H}=\mathfrak {H}_G\) [since the inner product \((\cdot ,\cdot )_G\) is equivalent to the original one \((\cdot ,\cdot )\)]. On the other hand, if \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) are definite subspaces, then \(\mathfrak {H}\not =\mathfrak {H}_G\) and \((\cdot ,\cdot )_G\) is not equivalent to \((\cdot , \cdot )\). In this case, the direct sum \(\mathcal {D}\subset \mathcal {D}_{max}\) may be nondensely defined in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) constructed by \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\).

We say that dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal if there exists an extension (1.3) such that the set \(\mathcal {D}\) remains dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) constructed by \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\).

In Sect. 4, dual quasi maximal subspaces are characterized in terms of extremal extensions of symmetric operators: Theorems 4.2, 4.5, Corollary 4.6. The theory of extremal extensions [2, 3] allows one to classify all possible cases: a Hilbert spaces \(\mathfrak {H}_G\) which preserve the density of \(\mathcal {D}\) exists and is uniquely defined (A); exists and is non-uniquely defined (B); does not exist (C).

Section 5 deals with the operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry. Each pair of dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) determines by (5.1) an operator \(\mathcal {C}_0\) such that \(\mathcal {C}_0^2=I\) and \(J\mathcal {C}_0\) is a positive symmetric operator in \(\mathfrak {H}\). The operator \(\mathcal {C}_0\) is called an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry if \(J\mathcal {C}_0\) is a self-adjoint operator in \(\mathfrak {H}\). In this case, the notation \(\mathcal {C}\) is used instead of \(\mathcal {C}_0\).

Let \(\mathcal {C}_0\) be an operator associated with dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \). Its extension to the operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry is equivalent to the construction of dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) in (1.3). This relationship allows one to use the classification \((A) - (C)\) in Sect. 4 for the solution of the following problems: (i) how many operators of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry can be constructed on the base of dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \)? (ii) is it possible to define an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry as the extension of \(\mathcal {C}_0\) by continuity in the new Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\)?

The concept of dual quasi maximal subspaces allows one to introduce quasi bases in Sect. 6. The characteristic properties of quasi bases are presented in Theorem 6.3 and Corollaries 6.4–6.6. The relevant examples are given. In particular, complex shifts of eigenfunctions of the harmonic oscillator are considered.

In what follows D(H), R(H), and \(\ker {H}\) denote, respectively, the domain, the range, and the kernel space of a linear operator H. The symbol \(H\upharpoonright _{\mathcal {D}}\) means the restriction of H onto a set \(\mathcal {D}\). Let \(\mathfrak {H}\) be a Hilbert space. Sometimes, it is useful to specify the inner product \((\cdot ,\cdot )\) endowed with \(\mathfrak {H}\). In this case the notation \((\mathfrak {H}, (\cdot ,\cdot ))\) will be used.

2 Dual Maximal Subspaces

Let \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\) be a Krein space with fundamental symmetry J. Denote

The subspaces \(\mathfrak {H}_{\pm }\) of \(\mathfrak {H}\) are orthogonal with respect to the initial inner product \((\cdot ,\cdot )\) as well as with respect to the indefinite inner product \([\cdot ,\cdot ]\). Moreover \(\mathfrak {H}_{+} \ (\mathfrak {H}_{-})\) is maximal uniformly positive (negative) with respect to \([\cdot ,\cdot ]\) and

The decomposition (2.1) is called a fundamental decomposition of the Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\).

I. Each positive (negative) subspace \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+\) (\({{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\)) in the Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\) can be presented as follows:

where \(K_{+} : \mathfrak {H}_+\rightarrow \mathfrak {H}_-\) and \(K_{-} : \mathfrak {H}_-\rightarrow \mathfrak {H}_+\) are strong contractionsFootnote 2 with domains \(D(K_{+})=M_+\subseteq \mathfrak {H}_+\) and \(D(K_{-})=M_-\subseteq \mathfrak {H}_-\), respectively. Therefore, the pair of subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) is determined by the formula

where

and \(P_{+}=\frac{1}{2}(I+J)\) and \(P_{-}=\frac{1}{2}(I-J)\) are orthogonal projection operators on \(\mathfrak {H}_+\) and \(\mathfrak {H}_-\), respectively.

By the construction, \(T_0\) is a strong contraction in \(\mathfrak {H}\) such that

and its domain \(D(T_0)=M_-\oplus {M_+}\) is a (closed) subspace in \(\mathfrak {H}\).

Lemma 2.1

The definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) in (2.2) are dual if and only if the operator \(T_0\) is a symmetric strong contraction in \(\mathfrak {H}\) and (2.4) holds.

Proof

It sufficient to establish that the orthogonality of \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) with respect to \([\cdot , \cdot ]\) is equivalent to the symmetricity of \(T_0\). For every \(x_{\pm }\in {M}_{\pm }\),

Hence, \((x_+, T_0x_-)=(T_0x_+, x_-)\). This relation is equivalent to

for every \(f=x_++x_-\) and \(g=y_++y_-\) from the domain of \(T_0\). Therefore, \(T_0\) is a symmetric operator. \(\square \)

The operator \(T_0\) characterizes the ‘deviation’ of definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) with respect to \(\mathfrak {H}_{\pm }\) and it allows to characterize the additional properties of \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \).

Lemma 2.2

[10] Let \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) be dual definite subspaces (i.e., the operator \(T_0\) satisfies the condition of Lemma 2.1). Then

-

(i)

the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are uniformly definite \(\iff \)\(\Vert T_0\Vert <1\);

-

(ii)

the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are definite \(\iff \)\(\Vert T_0\Vert =1\);

-

(iii)

the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are maximal \(\iff \)\(T_0\) is a self-adjoint operator in \(\mathfrak {H}\).

By virtue of Lemmas 2.1, 2.2, the extension of dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) to dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\)is equivalent to the extension of \(T_0\)to a self-adjoint strong contraction Tanticommuting with J. In this case cf. (2.2),

In what follows we assume that the direct sum\({\mathcal {D}}={{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\)of dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \)is a dense set in \(\mathfrak {H}\).

The next result is well known and it can be established by various methods (see, e.g., [6, 15]). For the sake of completeness, stages of the proof based on the Phillips work [15, Theorem 2.1] are given.

Theorem 2.3

Let \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) be dual definite subspaces. Then there exist dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) such that \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \).

Proof

For the construction of \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) we should prove the existence of a self-adjoint strong contractive extension \(T\supset {T_0}\) which anticommutes with J. The existence of a self-adjoint contractive extension \(T'\supset {T_0}\) is well known [5, 11]. However, we cannot state that \(T'\) anticommutes with J. To overcome this inconvenience we modify \(T'\) as follows:

The operator T is a self-adjoint contraction which anticommutes with J. Moreover, T is an extension of \(T_0\) (since \(JT_0=-T_0J\)). Therefore, the nonnegative/nonpositive subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) defined by (2.5) are dual and \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \). The existence of neutral elements (i.e., \(f\not =0\) with \([f, f]=0\)) in \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) is equaivalent to the existense of nontrivial isotropic vectors in \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) that is impossible since \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}[{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-^{max}\supset \mathcal {D}\) where \(\mathcal {D}\) is a dense set in \(\mathfrak {H}\). Hence, \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) are maximal definite. \(\square \)

Remark 2.4

It follows from the proof of Theorem 2.3 that each self-adjoint contractive extension \(T\supset {T_0}\) is a strong contraction.

The set of all self-adjoint contractive extensions of \(T_0\) forms an operator interval \([T_\mu , T_M]\) [5, \(\S \)108], [11]. The end points of this interval: \(T_\mu \) and \(T_M\) are called the hard and the soft extensions of \(T_0\), respectively.

Corollary 2.5

Let \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) be dual definite subspaces. Then their extension to the dual maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) can be defined by (2.5) with

Proof

Let us prove that

By virtue of [5, p. 380], the operators \(T_{\mu }\) and \(T_M\) have the form:

where T is a self-adjoint contractive extension of \(T_0\) anticommuting with J (its existence was proved in Theorem 2.3), \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\) are the orthogonal projections onto the orthogonal complements of the manifolds \(\sqrt{I+T}D(T_0)\) and \(\sqrt{I-T}D(T_0)\) respectively.

Obviously, \(J(I+T)=(I-T)J\). Then \(S^2=I-T\), where \(S=J\sqrt{I+T}J\). Hence, \(S=\sqrt{I-T}\) and \(J\sqrt{I+T}=\sqrt{I-T}J.\) The latter relation leads to the conclusion that, \(JQ_1=Q_2J\). The above analysis and (2.8) justifies (2.7).

Due to the proof of Theorem 2.3, for the construction of T in (2.6) we use an arbitrary self-adjoint contraction \(T'\supset {T_0}\). In particular, choosing \(T'=T_{\mu }\) and using (2.7), we complete the proof. \(\square \)

In general, the extension of dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) to dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) is not determined uniquely. To describe all possible cases we use the formula [2, 11]

which gives a one-to-one correspondence between all self-adjoint contractive extensions T of \(T_0\) and all nonnegative self-adjoint contractions X in the subspace \(\mathfrak {M}=\overline{R(T_M-T_\mu )}\).

Theorem 2.6

The self-adjoint contractive extension \(T\supset {T_0}\) determines dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supseteq {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) if and only if the corresponding nonnegative self-adjoint contraction X describing T in (2.9) is the solution of the following operator equation in \(\mathfrak {M}\):

Proof

It follows from (2.7) that the subspace \(\mathfrak {M}\) reduces J and \(J(T_M-T_\mu )^{\frac{1}{2}}=(T_M-T_\mu )^{\frac{1}{2}}J\). The last relation and (2.7) imply that the self-adjoint contraction T in (2.9) anticommutes with J if and only if X satisfies (2.10) Taking Remark 2.4 into account we complete the proof. \(\square \)

Remark 2.7

The equation (2.10) has an elementary solution \(X=\frac{1}{2}I\) which corresponds to the operator T defined in Corollary 2.5.

Let \(X_0\not =\frac{1}{2}I\) be a solution of (2.10). Then the nonnegative self-adjoint contraction \(X_1=I-X_0\) is also a solution of (2.10). Moreover, each self-adjoint nonnegative contraction \(X_\alpha =(1-\alpha )X_0+\alpha {X}_1, \ \alpha \in [0,1]\) is the solution of (2.10) Therefore, either dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are determined uniquely or there are infinitely many such extensions.

II. The above results as well as the results in the sequel can be rewritten with the use of the Cayley transform of \(T_0\):

The operator \(G_0\) is a closed densely defined positive symmetric operator in \(\mathfrak {H}\) with

and such that

It follows from Remark 2.4 that every nonnegative self-adjoint extension \(G\supset {G_0}\) (i.e. \((Gf,f)\ge {0}\)) is also a positive extension of \(G_0\) (i.e. \((Gf,f)>{0}\) for \(f\not =0\)).

Self-adjoint positive extensions G of \(G_0\) are in one-to-one correspondence with the set of contractive self-adjoint extensions of \(T_0\):

In particular, the Friedrichs extension \(G_{\mu }\) of \(G_0\) corresponds to the operator \(T_\mu \), while the Krein-von Neumann extension \(G_M\) is the Cayley transform of \(T_M\). The relation (2.7) between \(T_\mu \) and \(T_M\) is rewritten as follows [12]:

It follows from (2.11) and Lemmas 2.1, 2.2 (see also [12, Proposition 4.2]) that dual maximal definite subspaces\({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \)is in one-to-one correspondence with positive self-adjoint extensions Gof \(G_0\)satisfying the additional condition:

3 Krein Spaces Associated with Dual Maximal Subspaces

3.1 The Case of Maximal Uniformly Definite Subspaces

Let \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) be dual maximal uniformly definite subspaces. Then:

Relation (3.1) illustrates the variety of possible decompositions of the Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\) onto its maximal uniformly positive/negative subspaces. This property is characteristic for a Krein space and, sometimes, it is used for its definition [6].

With decomposition (3.1) one can associate a new inner product in \(\mathfrak {H}\):

(\( f=f_++f_-, \ g=g_++g_-, \ f_\pm , \ g_\pm \in {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\)). By virtue of (2.5), the relations \(f_\pm =(I+T)x_\pm \), \(g_\pm =(I+T)y_\pm \), \(x_\pm , y_\pm \in \mathfrak {H}_\pm \) hold. Taking (2.13) into account we rewrite (3.2) as follows:

Here G is a boundedFootnote 3 positive self-adjoint operator with \(0\in \rho (G)\). Therefore, the dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) determine the new inner product

which is equivalent to the initial one \((\cdot ,\cdot )\). The subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) are mutually orthogonal with respect to \((\cdot ,\cdot )_{G}\) in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\).

Summing up: the choice of various dual maximal uniformly definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\)generates infinitely many equivalent inner products \((\cdot ,\cdot )_{G}\)of the Hilbert space \(\mathfrak {H}\)but it does not change the initial Krein space\((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\).

3.2 The Case of Maximal Definite Subspaces

Assume that \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) are dual maximal definite subspaces. Then the direct sum

is a dense set in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}, (\cdot , \cdot ))\). The corresponding positive self-adjoint operator G is unbounded.

Similarly to the previous case, with direct sum (3.4) one can associate a new inner product \((\cdot ,\cdot )_G=(G\cdot ,\cdot )\) defined on \(D(G)=\mathcal {D}_{max}\) by the formula (3.2). The inner product \((\cdot ,\cdot )_G\) is not equivalent to the initial one and the linear space \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\) endowed with \((\cdot ,\cdot )_{G}\) is a pre-Hilbert space.

Let \(\mathfrak {H}_{G}\) be the completion of \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\) with respect to \((\cdot ,\cdot )_{G}\). The Hilbert space \(\mathfrak {H}_{G}\) does not coincide with \(\mathfrak {H}\). The dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) are orthogonal with respect to \((\cdot ,\cdot )_{G}\) and, by construction, the new Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_{G}, (\cdot ,\cdot )_{G})\) can be decomposed as follows:

where \({\hat{\mathfrak {L}}}_{\pm }^{max}\) are the completion of \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm ^{max}\) with respect to \((\cdot ,\cdot )_{G}\).

The decomposition (3.5) can be considered as a fundamental decomposition of the new Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}_{G}, [\cdot , \cdot ]_G)\) with the indefinite inner product

where \(f=f_{+}+f_{-}, \ g=g_{+}+g_{-}, \ f_{\pm }, g_{\pm } \in \hat{\mathfrak {L}}_{\pm }^{max}\) and \({J_G}f=f_{+}-f_{-}\) is the fundamental symmetry in \(\mathfrak {H}_G\).

Let \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\) be the energetic linear manifold constructed by the positive self-adjoint operator G. In other words, \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\) denotes the completion of \(D(G)=\mathcal {D}_{max}\) with respect to the energetic norm

The set of elements \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\) coincides with \(D(\sqrt{G})\) and the energetic linear manifold is a Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {D}[G], (\cdot ,\cdot )_{en})\) with respect to the energetic inner product

Comparing the definitions of \(\mathfrak {H}_G\) and \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\) leads to the conclusion that the energetic linear manifold \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\) coincides with the common part of \(\mathfrak {H}\) and \(\mathfrak {H}_G\), i.e., \(\mathfrak {D}[G]=\mathfrak {H}\cap \mathfrak {H}_G\).

Lemma 3.1

The indefinite inner products \([\cdot , \cdot ]\) and \([\cdot , \cdot ]_G\) coincide on \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\).

Proof

Indeed, taking (3.2) and (3.6) into account,

The obtained relation can be extended onto \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\) by the continuity because \(|[f,f]|=|[f,f]_G|\le {min}\{\Vert f\Vert ^2, \Vert f\Vert ^2_G \}\) for \(f\in {D}(G)\). \(\square \)

Summing up: the choice of various dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\)generates infinitely many Krein spaces \((\mathfrak {H}_G, [\cdot ,\cdot ]_G)\)such that the indefinite inner product \([\cdot ,\cdot ]_G\)coincides with the original indefinite inner product \([\cdot ,\cdot ]\)on the energetic linear manifold \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\). The inner products \((\cdot ,\cdot )\)and\((\cdot ,\cdot )_{G}\)considered on \(\mathfrak {D}[G]\)are not equivalent.

4 Dual Quasi Maximal Subspaces

4.1 Definition and Principal Results

Let \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) be dual definite subspaces and let \(G_0\) be the corresponding symmetric operator. Each positive self-adjoint extension G of \(G_0\) with condition (2.15) determines the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\).

Definition 4.1

Dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are called quasi maximal if there exists positive self-adjoint extension \(G\supset {G_0}\) with the condition (2.15) and such that the domain \(D(G_0)\) remains dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\).

Obviously, each dual maximal definite subspaces are quasi maximal. For dual uniformly definite subspaces, the concept of quasi-maximality is equivalent to maximality, i.e., each quasi maximal uniformly definite subspaces have to be maximal uniformly definite.

In general case of definite subspaces, the closure of dual quasi maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) with respect to \((\cdot ,\cdot )_G\) coincides with subspaces \(\hat{\mathfrak {L}}_\pm ^{max}\) in the fundamental decomposition (3.5), i.e., the closure of \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) in \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) gives dual maximal uniformly definite subspaces \(\hat{\mathfrak {L}}_\pm ^{max}\) of the new Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, [\cdot ,\cdot ]_G)\).

It is natural to suppose that the quasi maximality can be characterized in terms of the corresponding positive self-adjoint extensions G of \(G_0\). For this reason, we recall [2, 3] that a nonnegative self-adjoint extension G of \(G_0\) is called an extremal extension if

The Friedrichs extension \(G_\mu \) and the Krein-von Neumann extension \(G_M\) are examples of extremal extensions of \(G_0\).

Theorem 4.2

Dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal if and only if there exists an extremal extension G of \(G_0\) which satisfies (2.15)

Proof

Since \(\Vert \phi -f\Vert ^2_{G}=(G(\phi -f),(\phi -f))\), the condition (4.1) means that each element \(\phi \in {D}(G)={{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-^{max}\) can be approximated by elements \(f\in {D}(G_0)={{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_{G}, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) if and only if G is an extremal extension of \(G_0\). \(\square \)

Remark 4.3

In general, an extremal extension G of \(G_0\) is not determined uniquely. Let \(G_i,\)\(i=1,2\) be extremal extensions of \(G_0\) that satisfy (2.15). By virtue of (3.2), the operator

defined as \(Wf=f\) for \(f\in {D}(G_0)\) and extended by continuity onto \((\mathfrak {H}_{G_1}, (\cdot ,\cdot )_{G_1})\) is a unitary mapping between \(\mathfrak {H}_{G_1}\) and \(\mathfrak {H}_{G_2}\). Moreover, \(WJ_{G_1}=J_{G_2}W\), where \(J_{G_i}\) are the fundamental symmetry operators corresponding to the fundamental decompositions \(\mathfrak {H}_{G_i}=(\hat{\mathfrak {L}}_{+}^{i})^{max}\oplus _{G_{i}}(\hat{\mathfrak {L}}_{-}^{i})^{max}\) of the Krein spaces \((\mathfrak {H}_{G_i}, [\cdot ,\cdot ]_{G_i})\). Therefore, the indefinite inner products of these spaces satisfy the relation

and they are extensions (by the continuity) of the original indefinite inner product \([\cdot ,\cdot ]\) defined on \(D(G_0)\). For this reason, the Krein spaces \((\mathfrak {H}_{G_i}, [\cdot ,\cdot ]_{G_i})\) corresponding to different extremal extensions are unitary equivalent and we can identify them.

Sufficient conditions of quasi maximality are presented below.

Proposition 4.4

Dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal if one of the equivalent conditions is satisfied:

-

(i)

the operator \(G_0\) has a unique nonnegative self-adjoint extension;

-

(ii)

dual maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are determined by the Friedrichs extension \(G_\mu \) of \(G_0\) (i.e., \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}=(I+T_\mu )\mathfrak {H}_{\pm }\));

-

(iii)

for all nonzero vectors \(g\in \ker (I+G_0^*)=\mathfrak {H}\ominus (M_-\oplus {M_+})\)

$$\begin{aligned} \inf _{f\in {D}(G_0)}\frac{(G_0f,f)}{|(f,g)|^2}=0; \end{aligned}$$ -

(iv)

for all nonzero vectors \(g\in \mathfrak {H}\ominus {D(T_0)}=\mathfrak {H}\ominus (M_-\oplus {M_+})\)

$$\begin{aligned} \sup _{x\in {D}(T_0)}\frac{|(T_0x, g)|^2}{\Vert x\Vert ^2-\Vert T_0x\Vert ^2}=\infty . \end{aligned}$$(4.2)

Proof

Let \(G_0\) be a unique nonnegative self-adjoint extension G. Then, \(G=G_\mu =G_M\) and, by virtue of (2.14), \(JG=G^{-1}J\). Therefore, the operator G determines dual maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \). Furthermore, G is an extremal extension (since the Friedrichs extension and the Krein-von Neumann extension are extremal). In view of Theorem 4.2, \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal. Thus, the condition (i) ensures the quasi maximality of \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \).

The condition (ii) is equivalent to (i) due to (2.14) and (2.15). The equivalence (i) and (iii) follows form [11, Theorem 9]. The condition (i) reformulated for the Cayley transform \(T_0\) of \(G_0\) [see (2.11)] means that \(T_0\) has a unique self-adjoint contractive extension \(T=T_\mu =T_M\). The latter is equivalent to (iv) due to [11, Theorem 6]. \(\square \)

Assume that dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) do not satisfy conditions of Proposition 4.4. Then \(T_\mu \not =T_M\) and the subspace \(\mathfrak {M}=\overline{R(T_M-T_\mu )}\) of \(\mathfrak {H}\) is nontrivial. In view of (2.7), this subspace reduces the operator J. Therefore, the restriction of J onto \(\mathfrak {M}\) determines the operator of fundamental symmetry in \(\mathfrak {M}\) and the space \(\mathfrak {M}\) endowed with the indefinite inner product \([\cdot ,\cdot ]\) is the Krein space \((\mathfrak {M}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\).

A subspace \(\mathfrak {M}_1\subset \mathfrak {M}\) is called hypermaximal neutral if the space \(\mathfrak {M}\) can be decomposed \(\mathfrak {M}=\mathfrak {M}_1\oplus {J}\mathfrak {M}_1\).

A Krein space contains hypermaximal neutral subspaces if and only if the dimension of a maximal uniformly positive subspace coincides with the dimension of a maximal uniformly negative subspace [6].

Theorem 4.5

Let dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) do not satisfy conditions of Proposition 4.4. Then \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal subspaces if and only if the Krein space \((\mathfrak {M}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\) contains a hypermaximal neutral subspace.

Proof

Assume that \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal. By Theorem 4.2, there exists an extremal extension \(G\supset {G}_0\) with condition (2.15). Let T be the Cayley transform of G, see (2.13). By virtue of Theorem 2.6, the operator T is described by (2.9), where X is a solution of (2.10). Due to [2, Section 7], extremal extensions are specified in (2.9) by the assumption that X is an orthogonal projection in \(\mathfrak {M}\). Denote \(\mathfrak {M}_1=X\mathfrak {M}\) and \(\mathfrak {M}_2=(I-X)\mathfrak {M}\). Since X is the solution of (2.10) we decide that \(J\mathfrak {M}_1=\mathfrak {M}_2\). Therefore, \(\mathfrak {M}=\mathfrak {M}_1\oplus {J}\mathfrak {M}_1\) and \(\mathfrak {M}_1\) is a hypermaximal neutral subspace of the Krein space \((\mathfrak {M}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\).

Conversely, let a hypermaximal neutral subspace \(\mathfrak {M}_1\) be given. Then \(\mathfrak {M}=\mathfrak {M}_1\oplus {J}\mathfrak {M}_1\) and the orthogonal projection X on \(\mathfrak {M}_1\) is the solution of (2.10). The formula (2.9) with given X determines the self-adjoint strong contraction T anticommuting with J and its Cayley transform G defines the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) in which \(D(G_0)\) is a dense set. \(\square \)

Corollary 4.6

Let the Krein space \((\mathfrak {M}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\) contain a hypermaximal neutral subspace. Then there exist infinitely many extensions of \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) to dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) such that \(\mathcal {D}={{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) is a dense set in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) associated with \(\mathcal {D}_{max}={{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-^{max}\) and, at the same time, there exist infinitely many extensions \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) such that \(\mathcal {D}\) is not dense in the corresponding Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\).

Proof

It follows from the proof of Theorem 4.5 that a hypermaximal neutral subspace \(\mathfrak {M}_1\) determines the dual maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) such that \(\mathcal {D}\) is a dense set in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) associated with \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\). Precisely, the orthogonal projection X on \(\mathfrak {M}_1\) defines the required subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) by the formulas (2.5) and (2.9). Therefore, one can construct infinitely many such extensions \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) because there are infinitely many hypermaximal neutral subspaces in the Krein space \((\mathfrak {M}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\).

If X is the orthogonal projection on \(\mathfrak {M}_1\), then \(I-X\) is the orthogonal projection on the hypermaximal neutral subspace \(J\mathfrak {M}_1\). These operators are solutions of (2.10). In this case, the nonnegative self-adjoint contractions \(X_\alpha =(1-\alpha )X+\alpha (I-X), \ \alpha \in (0,1)\) are solutions of (2.10) and they also determine dual maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}(\alpha )\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) via (2.5) and (2.9). The linear manifold \(\mathcal {D}\) cannot be dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) associated with \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}(\alpha )[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-^{max}(\alpha )\) because \(X_\alpha \) loses the property of being projection operator (since \(X_\alpha ^2\not =X_\alpha \)). \(\square \)

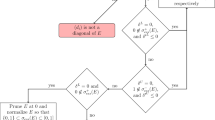

By virtue of the results above, one can classify dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) in dependence of properties of the soft \(T_M\) and the hard \(T_\mu \) extensions of \(T_0\). Precisely:

-

(A)

\(T_\mu =T_M\)\(\iff \) the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal, there is a unique extension of \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) to dual maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\)

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal {D}={{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_- \ \rightarrow \ \mathcal {D}_{max}={{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-^{max} \end{aligned}$$and the linear manifold \(\mathcal {D}\) is dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) associated with \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\);

-

(B)

\(T_\mu \not =T_M\) and the Krein space \((\mathfrak {M}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\) contains hypermaximal neutral subspaces \(\iff \) the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal, there are infinitely many extensions \(\mathcal {D}\rightarrow \mathcal {D}_{max}\) such that \(\mathcal {D}\) is dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) associated with \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\) and simultaneously, there are infinitely many extensions \(\mathcal {D}\rightarrow \mathcal {D}_{max}\) for which \(\mathcal {D}\) cannot be a dense set in \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\);

-

(C)

\(T_\mu \not =T_M\) and the Krein space \((\mathfrak {M}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\) does not contain hypermaximal neutral subspaces \(\iff \) the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are not quasi maximal, the total amount of possible extensions \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \rightarrow {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) is not specified (a unique extension is possible as well as infinitely many ones), the linear manifold \(\mathcal {D}\) is not dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) associated with \(\mathcal {D}_{max}\).

4.2 Examples

4.2.1 Auxiliary Statement

Let \(\mathfrak {L}_{\pm }\) be dual definite subspaces and let \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset \mathfrak {L}_{\pm }\) be dual maximal definite subspaces. The subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) are described by (2.5), where T is a self-adjoint strong contraction anticommuting with J. Similarly, the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are determined by (2.2), where \(T_0\) is the restriction of T onto \(D(T_0)=M_+\oplus {M_-}\) where \(M_\pm \) are subspaces of \(\mathfrak {H}_\pm \). Denote

The operator \(\Xi \) is a positive self-adjoint contraction in \(\mathfrak {H}\) which leaves the subspaces \(\mathfrak {H}_{\pm }\) invariant.

Lemma 4.7

The direct sum \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) is a dense set in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) associated with the sum \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-^{max}\) of dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset \mathfrak {L}_{\pm }\) if and only if

Proof

It follows from (3.3):

Therefore, \(\{{f}_n\}\) (\(f_n\in {D}(G)\)) is a Cauchy sequence in \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) if and only if \(\{\Xi {x_n}\}\) is a Cauchy sequence in \((\mathfrak {H}, (\cdot ,\cdot ))\). This means that a one-to-one correspondence between \(\mathfrak {H}_G\) and \(\mathfrak {H}\) can be established as follows:

Let as assume that \(F\in \mathfrak {H}_G\) is orthogonal to \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\). Then \(F=F_\gamma \), where \(\gamma \in \mathfrak {H}\) and for all \(f\in {{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-=(I+T)D(T_0)\)

where \(x_0\) runs \(D(T_0)\). By virtue of (2.3) and (4.4), \(\gamma =0\). Therefore, \(F_\gamma =0\). \(\square \)

4.2.2 How to Construct Dual Quasi Maximal Subspaces?

We consider below an example (inspired by [1, 13]) which illustrates a general method of the construction of dual quasi maximal subspaces.

Let \(\{\gamma _n^+\}\) and \(\{\gamma _n^-\}\) be orthonormal bases of subspaces \(\mathfrak {H}_{\pm }\) in the fundamental decomposition (2.1). Every \(\phi \in {\mathfrak {H}}\) has the representation

where \(\{c_n^\pm \}\in {l_2({\mathbb {N}})}\). The operator

is a self-adjoint strong contraction anticommuting with the fundamental symmetry J of the Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\).

The subspaces \(\mathfrak {L}_{\pm }^{max}\) defined by (2.5) with the operator T above are dual maximal definite. But they cannot be uniformly definite since \(\Vert T\Vert =1\), see Lemma 2.2.

Let us fix elements \(\chi ^{\pm }{\in }\mathfrak {H}\),

and define the following subspaces of \(\mathfrak {H}_\pm \):

Proposition 4.8

The dual definite subspaces

are quasi maximal for \(\frac{1}{2}<\delta \le \frac{3}{2}\). In particular, \(\frac{1}{2}<\delta \le {1}\) corresponds to the case (A); the case (B) holds when \(1<\delta \le \frac{3}{2}\).

Proof

First of all we note that \(\mathcal {D}={{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) is a dense set in \(\mathfrak {H}\) for \(\frac{1}{2}<\delta \le \frac{3}{2}\) [1, p. 317].

The subspaces \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) in (4.8) are the restriction of dual maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}=(I+T)\mathfrak {H}\). Let us show that, for \(\frac{1}{2}<\delta \le {1}\), the set \(\mathcal {D}\) is dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) associated with \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\). Due to Lemma 4.7, one should check (4.4). In view of (4.5), (4.6):

On the other hand, \(\mathfrak {H}\ominus (M_-\oplus {M_+})=\text{ span }\{\chi ^+, \chi ^{-}\}\). Hence, the set \(R(\Xi )\cap (\mathfrak {H}\ominus (M_-\oplus {M_+}))\) contains nonzero elements if and only if

that is impossible for \(\frac{1}{2}<\delta \le {1}\). Therefore, relation (4.4) holds and \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) are quasi maximal subspaces. By [1, Proposition 6.3.9], the dual subspaces \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) have a unique extension to dual maximal subspaces when \(\frac{1}{2}<\delta \le {1}\) that corresponds to the case (A).

If \({1}<\delta \le \frac{3}{2}\), then the set \(\mathcal {D}\) cannot be dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) considered above. However, for such \(\delta \), the dual subspaces \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) can be extended to different pairs of dual maximal subspaces [1, Proposition 6.3.9]. This means that \(T_\mu \not =T_M\) and the space \(\mathfrak {M}=\overline{R(T_M-T_\mu )}\) is not trivial. The operators \(T_\mu , T_M\) are extensions of \(T_0\). Hence, they coincide on \(D(T_0)=M_-\oplus {M_+}\). Taking into account that \(\mathfrak {H}=\mathfrak {M}\oplus \ker (T_M-T_\mu )\), we conclude that \(\mathfrak {M}\subset \text{ span }\{\chi ^+, \chi ^{-}\}\). Moreover, \(\mathfrak {M}=\text{ span }\{\chi ^+, \chi ^{-}\}\). Indeed, if \(\dim \mathfrak {M}=1\), then the operator J in (2.10) coincides with \(+I\) (or \(-I\)). In this case, the Eq. (2.10) has a unique solution \(X=\frac{1}{2}I\) and, by Theorem 2.6, there exists a unique extension \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset \mathfrak {L}_\pm \) that is impossible. Therefore, \(\dim \mathfrak {M}=2\) and \(\mathfrak {M}=\text{ span }\{\chi ^+, \chi ^{-}\}\). The Krein space \((\text{ span }\{\chi ^+, \chi ^{-}\}, [\cdot , \cdot ])\) contains infinitely many hypemaximal neutral subspaces. By Theorem 4.5, there are infinitely many extensions \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset \mathfrak {L}_\pm \), \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\not =(I+T)\mathfrak {H}\) such that \(\mathcal {D}\) is a dense set in the corresponding Hilbert spaces \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\). Therefore, \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm \) are quasi maximal [the case (B)]. \(\square \)

4.2.3 The Uniqueness of Dual Maximal Extension \({\mathfrak {L}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) Does Not Mean that \({\mathfrak {L}}_\pm \) are Quasi Maximal

Let us assume that \(\chi ^+=0\) and \(\chi ^{-}\) is defined as in (4.7). Then \(M_+=\mathfrak {H}_+\) and the subspace \(\mathfrak {L}_+\) in (2.14) coincides with \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}\). This means that the dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are determined uniquely. Precisely, \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}=\mathfrak {L}_{+}\) and

where \(\mathfrak {L}_{+}^{[\perp ]}\) denotes the maximal negative subspace orthogonal to \(\mathfrak {L}_{+}\) with respect to the indefinite inner product \([\cdot , \cdot ]\).

Reasoning by analogy with the proof of Proposition 4.8 we obtain that the dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}\) and \(\mathfrak {L}_-\) are quasi maximal (the case (A) of the classification above) for \(\frac{1}{2}<\delta \le {1}\).

If \(1<\delta \le \frac{3}{2}\), then the direct sum \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) cannot be dense in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) constructed by \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\). Since the extension \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) is determined uniquely, the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}\) and \(\mathfrak {L}_-\) cannot be quasi maximal (the case (C) of the classification above).

5 Operators of \(\mathcal {C}\)-Symmetry Associated with Dual Maximal Definite Subspaces

An operator \(\mathcal {C}_0\)associated with dual definite subspaces\({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) is defined as follows: its domain \(D(\mathcal {C}_0)\) coincides with \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) and

If \(\mathcal {C}_0\) is given, then the corresponding dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are recovered by the formula \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm =\frac{1}{2}(I\pm \mathcal {C}_0)D(\mathcal {C}_0)\).

Proposition 5.1

The following are equivalent:

-

(i)

\(\mathcal {C}_0\) is determined by dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) with the use of (5.1);

-

(ii)

\(\mathcal {C}_0\) satisfies the relation \(\mathcal {C}_0^2f=f\) for all \(f\in {D(\mathcal {C}_0)}\) and \(J\mathcal {C}_0\) is a closed densely defined positive symmetric operator in \(\mathfrak {H}\).

Proof

In view of (5.1), \(\mathcal {C}_0^2f=f\) for all \(f\in {D(\mathcal {C}_0)}\) and

Taking into account the definition (2.11) of \(G_0\) and formulas (3.2), (3.3), we obtain that \(G_0=J\mathcal {C}_0\), where \(G_0\) is a closed densely defined positive symmetric operator in \(\mathfrak {H}\). The implication \((i)\rightarrow (ii)\) is proved.

\((ii)\rightarrow (i)\). The Cayley transform \(T_0\) of \(G_0=J\mathcal {C}_0\) is a symmetric strong contraction in \(\mathfrak {H}\) (since \(G_0\) is positive symmetric). Moreover, the condition \(\mathcal {C}_0^2=I\) on \(\mathcal {D}(\mathcal {C}_0)\) means that \(T_0\) satisfies (2.4). Substituting \(T_0\) into (2.2) we obtain the required dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) which generate \(\mathcal {C}_0\) with the help of (5.1). \(\square \)

We say that \(\mathcal {C}_0\) is an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry if \(\mathcal {C}_0\) is associated with dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\). In this case, the notation \(\mathcal {C}\) will be used instead of \(\mathcal {C}_0\). An operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry admits the presentation \(\mathcal {C}=Je^Q\), where Q is a self-adjoint operator in \(\mathfrak {H}\) such that \(JQ=-QJ\) [12].

Let \(\mathcal {C}_0\) be an operator associated with dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \). Its extension to the operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry \(\mathcal {C}\) is equivalent to the construction of dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset \mathfrak {L}_{\pm }\). By Theorem 2.3, each operator \(\mathcal {C}_0\) can be extended to an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry which, in general, is not determined uniquely. Its choice \(\mathcal {C}\supset \mathcal {C}_0\) determines the new Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\), where

If \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal, then there exists a dual maximal extension \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) such that \(\mathcal {C}_0\) is extended to \(\mathcal {C}\) by continuity in the new Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) generated by \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\).

If the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are not quasi maximal, then the sum \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) is non dense in each Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) constructed by dual maximal subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\supset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \). In this case, an extension by continuity of \(\mathcal {C}_0\) to an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry is impossible. In other words, all possible extensions of \(\mathcal {C}_0\) to an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry generate Hilbert spaces \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) each of which contains a nontrivial part \(\mathfrak {H}_G\ominus _G({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-)\) that has no direct relationship to the original dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \).

Summing up, we can rephrase the classification in Sect. 4.1 as follows:

-

(A’)

the extension of \(\mathcal {C}_0\) to an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry is unique and it coincides with the extension of \(\mathcal {C}_0\) by continuity in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\), where \(G=G_\mu \) is the Friedrichs extension of \(G_0\);

-

(B’)

the extension of \(\mathcal {C}_0\) to an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry is not unique. Infinitely many operators \(\mathcal {C}\) can be realized via the extension of \(\mathcal {C}_0\) by continuity in the corresponding Hilbert spaces \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\). At the same time, there exist infinitely many extensions \(\mathcal {C}\supset \mathcal {C}_0\) which generate Hilbert spaces \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\) containing the closure of \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) as a proper subspace;

-

(C’)

there is no extension of \(\mathcal {C}_0\) to an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry by continuity in the corresponding Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\). The total amount of possible extensions \(\mathcal {C}\supset \mathcal {C}_0\) is not specified (a unique extension is possible as well as infinitely many ones).

6 J-Orthonormal Quasi Bases

6.1 Quasi Bases

A sequence \(\{f_n\}\) is called orthonormal in the Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\) (briefly, J-orthonormal) if \(\{f_n\}\) is orthonormalized with respect to the indefinite inner product, i.e., if \(|[f_n, f_m]|=\delta _{nm}\). In what follows, the sequence \(\{f_n\}\) is assumed to be complete (i.e., the span of \(\{f_n\}\) is a densely defined set in \(\mathfrak {H}\)).

Separating the sequence \(\{f_n\}\) by the signs of \([f_n,f_n]\):

we obtain two sequences of positive \(\{f_n^+\}\) and negative \(\{f_n^-\}\) elements. Denote by \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+\) and \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) the closure [in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}, (\cdot , \cdot ))\)] of the linear spans generated by the sets \(\{f_n^+\}\) and \(\{f_n^-\}\), respectively. By the construction, \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are dual definite subspaces and their direct sum (1.2) is dense in \({{\mathfrak {H}}}\).

Definition 6.1

A complete J-orthonormal sequence \(\{f_n\}\) is called a quasi basis of the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}, (\cdot , \cdot ))\) if the corresponding dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal.

If a J-orthonormal sequence \(\{f_n\}\) is a basis in \(\mathfrak {H}\), then the dual subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are maximal definite [6, Statement 10.12 in Chapter 1]. Therefore, \(\{f_n\}\) is a quasi basis in \(\mathfrak {H}\).

Proposition 6.2

Let a J-orthonormal sequence \(\{f_n\}\) be a quasi basis in \(\mathfrak {H}\), then its biorthogonal sequence \(\{\gamma _n=\text{ sign }([f_n,f_n])Jf_n\}\) is also a quasi basis.

Proof

The biorthogonal sequence \(\{\gamma _n\}\) determines the dual definite subspaces \(J{{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \). The corresponding positive symmetric operator associated with \(J{{\mathfrak {L}}}_+[\dot{+}]J{{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\) [see (2.11)] coincides with \(G_0^{-1}\). By Theorem 4.2 there exists an extremal extension \(G\supset {G_0}\) which satisfies (2.15). Then, \(G^{-1}\) is an extremal extension of \(G_0^{-1}\) which also satisfies (2.15). Therefore, \(J{{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are quasi maximal. \(\square \)

Theorem 6.3

Let \(\{f_n\}\) be a complete J-orthonormal sequence in \(\mathfrak {H}\) and let the operator \(\mathcal {C}_0\) be associated with subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) generated by \(\{f_n\}\). The following are equivalent:

-

(i)

\(\{f_n\}\) is a quasi basis of \(\mathfrak {H}\);

-

(ii)

there exists an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry \(\mathcal {C}\supset \mathcal {C}_0\) such that \(\{f_n\}\) turns out to be an orthonormal basis in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot , \cdot )_G)\) generated by \(\mathcal {C}\).

-

(iii)

there exists a self-adjoint operator Q in the Hilbert space \(\mathfrak {H}\), which anticommutes with J and such that the sequence \(\{g_n=e^{Q/2}f_n\}\) is an orthonormal basis of \(\mathfrak {H}\) and each \(g_n\) belongs to one of the subspaces \(\mathfrak {H}_\pm \) of the fundamental decomposition (2.1).

Proof

\((i)\rightarrow (ii)\). If \(\{f_n\}\) is a quasi basis, then there exists an extremal extension \(G\supset {G_0}\) which satisfies (2.15) and the linear span of \(\{f_n\}\) is dense in \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot , \cdot )_G)\). It follows from (3.2) and (5.2) that

Therefore, \(\{f_n\}\) is an orthonormal basis in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot , \cdot )_G)\). The inverse implication \((ii)\rightarrow (i)\) is obvious.

\((ii)\rightarrow (iii)\). In view of (5.2), \(\mathcal {C}=Je^Q\) and \(G=e^Q\), where Q is a self-adjoint operator anticommuting with J. In this case, the relation (6.2) takes the form \((e^{Q/2}f_n, e^{Q/2}f_m)=\delta _{nm}\). Hence, \(\{g_n=e^{Q/2}f_n\}\) is an orthonormal sequence in \(\mathfrak {H}\). Its completeness will be established with the use of Lemma 4.7. Before doing this we note that the dual maximal definite subspaces \(\mathfrak {L}_\pm ^{max}=\frac{1}{2}(I\pm \mathcal {C})D(\mathcal {C})\) corresponding to \(\mathcal {C}=Je^Q\) are also given by (2.5) with \(T=-\tanh \frac{Q}{2}\) [12]. Therefore, the bounded operator \(\Xi \) in (4.3) coincides with \(\cosh ^{-1}{Q/2}\), where \(\cosh {Q/2}=\frac{1}{2}(e^{Q/2}+e^{-Q/2})\).

Since \(g_n=e^{Q/2}f_n\) and \(f_n\in {D(G)=D(e^Q)}\), every \(g_n\) belongs to the domain of definition of \(\cosh {Q/2}\) and

Comparing the obtained relation with (2.2) and taking into account that the subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \subset {{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) coincide with the closure of \(\text{ span }\{f_n^\pm \}\), we conclude that \(D(T_0)=M_-\oplus {M_+}\) coincides with the closure of \(\text{ span }\{\cosh {Q}/{2}g_n\}\). Therefore,

Let \(u\in \mathfrak {H}\) be orthogonal to \(\{g_n\}\). Then

and hence, \(\cosh ^{-1}{Q/2}u\in {R}(\Xi )\cap (\mathfrak {H}\ominus (M_-\oplus {M_+}))\). By virtue of Lemma 4.7, \(\cosh ^{-1}{Q/2}u=0\). This means that \(u=0\) and \(\{g_n\}\) is a complete orthonormal sequence in \(\mathfrak {H}\), i.e., \(\{g_n\}\) is a basis in \(\mathfrak {H}\).

It follows from (2.2) and (6.3), that \(\cosh {Q}/{2}g_n\) belongs to one of the subspaces \(\mathfrak {H}_\pm \) (depending on either \(f_n\in {{\mathfrak {L}}}_+\) or \(f_n\in {{\mathfrak {L}}}_-\)). The same property is true for \(g_n\) because \(g_n=\Xi \cosh {Q}/{2}g_n\) and \(\Xi : \mathfrak {H}_\pm \rightarrow \mathfrak {H}_\pm \).

\((iii)\rightarrow (ii)\). Since \(g_n=e^{Q/2}f_n\) belongs to \(\mathfrak {H}_\pm \), we get \(Jg_n=\pm {g_n}=Je^{Q/2}f_n=e^{-Q/2}Jf_n\). Therefore, \(g_n\in {D(e^{Q/2})}\cap {D}(e^{-Q/2})\). This means that the sequence \(\{\cosh {Q}/{2}g_n\}\) is well defined and \(f_n\in {D}(e^Q)\).

For given Q we define the operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry \(\mathcal {C}=Je^Q\) and \(G=e^Q\). By analogy with (6.2),

Therefore, \(\{f_n\}\) is an orthonormal sequence in \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot , \cdot )_G)\).

It follows form (6.4) that the sequence \(\{Gf_n\}\) is biorthogonal to \(\{f_n\}\) (in the Hilbert space \(\mathfrak {H}\)). Hence, \(Gf_n=sign([f_n,f_n])Jf_n\) and \(\mathcal {C}{f}_n=sign([f_n,f_n])f_n\). The latter means that \(\mathcal {C}\) is an extension of the operator \(\mathcal {C}_0\) defined by (5.1) and the dual maximal definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm ^{max}\) determined by \(\mathcal {C}\) are extensions of the dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) generated as the closures of \(\text{ span }\{f_n^{\pm }\}\). This fact and (6.3) lead to the conclusion that \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are determined by (2.2), where \(D(T_0)=M_-\oplus {M_+}\) coincides with the closure of \(\text{ span }\{\cosh {Q}/{2}g_n\}\).

Assume that \(\{f_n\}\) is not complete in \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot , \cdot )_G)\). Then the direct sum of \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) cannot be dense in \(\mathfrak {H}_G\) and, by Lemma 4.7 (since \(\Xi =\cosh ^{-1}{Q/2}\)) there exists \(p=\cosh ^{-1}{Q/2}u\not =0\) such that, for all \(g_n\),

that is impossible (since \(\{g_n\}\) is a basis of \(\mathfrak {H}\)). The obtained contradiction implies that \(\{f_n\}\) is an orthonormal basis of \(\mathfrak {H}_G\). \(\square \)

Corollary 6.4

Let \(\{f_n\}\) be a quasi basis of \(\mathfrak {H}\). Then there exists an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry \(\mathcal {C}=Je^{Q}\) such that for elements of the energetic linear manifold \(g\in \mathfrak {D}[G]\subset \mathfrak {H}\):

where the series converge in the Hilbert spaces \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot , \cdot )_G)\) and \((\mathfrak {H}, (\cdot , \cdot ))\), respectively.

Proof

By Theorem 6.3, there exists an operator \(\mathcal {C}=Je^{Q}\) such that \(\{f_n\}\) is an orthonormal basis in \(\mathfrak {H}_G\). The energetic linear manifold \(\mathfrak {D}[G]=D(e^{Q/2})\) coincides with \(\mathfrak {H}\cap \mathfrak {H}_G\) (see Sect. 3.2). Hence, each \(g\in \mathfrak {D}[G]\) can be presented as \(g=\sum _{n=1}^\infty {c_n}f_n\), where the series converges in \(\mathfrak {H}_{G}\) and \(c_n=(g, f_n)_G=(e^{Q/2}g, e^{Q/2}f_n)=(g, e^{Q}f_n)=[g, {\mathcal {C}}f_n].\) Similarly, each \(e^{Q/2}g\) admits the decomposition \(e^{Q/2}g=\sum _{n=1}^\infty {c_n'}e^{Q/2}f_n\), where the series converges in \(\mathfrak {H}\) and \(c_n'=(e^{Q/2}g, e^{Q/2}f_n)=[g, {\mathcal {C}}f_n].\)\(\square \)

Corollary 6.5

Let \(\{f_n\}\) be a quasi basis of \(\mathfrak {H}\). Then an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry arising in items (ii), (iii) of Theorem 6.3 acts as follows:

where the series are convergent in \(\mathfrak {H}_G\) and \(\mathfrak {H}\), respectively.

Proof

The formulas above follow from the corresponding formulas in (6.5) with \(g=\mathcal {C}{f}\) and \(g=e^{-Q/2}\mathcal {C}{f}\), respectively. \(\square \)

An operator H in a Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot , \cdot ])\) is called J-symmetric if \([Hf, g]=[f, Hg]\) for all \(f,g\in {D}(H)\).

Corollary 6.6

If eigenfunctions \(\{f_n\}\) of a J-symmetric operator H form a quasi basis in \(\mathfrak {H}\), then there exists an operator of \(\mathcal {C}\)-symmetry \(\mathcal {C}\) such that the operator H restricted on \(\text{ span }\{f_n\}\) turns out to be essentially self-adjoint in the Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_{G})\) generated by \(\mathcal {C}\).

Proof

Due to Theorem 6.3 there exists an operator \(\mathcal {C}\) such that \(\{f_n\}\) is a basis of \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_{G})\). The restriction of \(\mathcal {C}\) on \(\text{ span }\{f_n\}\) coincides with the operator \(\mathcal {C}_0\) defined by (5.1) (here \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_\pm \) are the closures of \(\text{ span }\{f_n^{\pm }\}\)). It is easy to see that

Taking (3.2), (3.3) into account, we obtain

for all \(f, g\in \text{ span }\{f_n\}\). Hence H is symmetric in \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_{G})\) and eigenvalues of H corresponding to eigenfunctions \(f_n\) must be real. Therefore, \(R(H\pm {i}I)\supset \text{ span }\{f_n\}\) and the operator H is essentially self-adjoint in \(\mathfrak {H}_G\). \(\square \)

6.2 Examples

Quasi-bases can be easy constructed with the use of Theorem 6.3. Indeed let us consider an orthonormal basis \(\{g_n\}\) of \(\mathfrak {H}\) such that each \(g_n\) belongs to one of the subspaces \(\mathfrak {H}_\pm \) in the fundamental decomposition (2.1). Let Q be a self-adjoint operator in \(\mathfrak {H}\), which anticommutes with J. If all \(g_n\) belong to the domain of definition of \(e^{-Q/2}\) then \(f_n=e^{-Q/2}g_n\) is an J-orthonormal system of the Krein space \((\mathfrak {H}, [\cdot ,\cdot ])\). Assuming additionally that \(\{f_n\}\) is complete in \(\mathfrak {H}\), we get an example of quasi basis.

I. Let \(\mathfrak {H}=L_2(\mathbb {R})\) and let \(J=\mathcal {P}\) be the space parity operator \(\mathcal {P}f(x)=f(-x)\). The subspaces \(\mathfrak {H}_{\pm }\) of the fundamental decomposition (2.1) coincide with the subspaces of even and odd functions of \(L_2(\mathbb {R})\).

The Hermite functions

are eigenfunctions of the harmonic oscillator and they form an orthonormal basis of \(L_2(\mathbb {R})\). The functions \(g_n\) are either odd or even functions. Therefore, \(g_n\in \mathfrak {H}_+\) or \(g_n\in \mathfrak {H}_-\).

Since Hermitian functions are entire functions, the complex shift of \(g_n\) can be defined:

The sequence \(\{f_n\}\) is complete in \(L_2(\mathbb {R})\) [14, Lemma 2.5]. Applying the Fourier transform \(Ff=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi }}\int _{-\infty }^\infty {e^{-ix\xi }}f(x)dx\) to \(f_n\) we get \(Ff_n=e^{-a\xi }Fg_n\). Therefore, \(f_n=F^{-1}e^{-a\xi }Fg_n\). The last relation can be rewritten as

The operator Q is self-adjoint in \(L_2(\mathbb {R})\) and in anticommutes with \(\mathcal {P}\). Therefore, \(\{f_n\}\) is a quasi basis of \(L_2(\mathbb {R})\). The functions \(\{f_n\}\) are simple eigenfunctions of the \(\mathcal {P}\)-symmetric operator

Therefore, H restricted on \(\text{ span }\{f_n\}\) is essentially self-adjoint in the new Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\), where \(\mathfrak {H}_G\) is the completion of \(\text{ span }\{f_n\}\) with respect to the norm: \(\Vert f\Vert ^2_G=(e^Qf,f)=(F^{-1}e^{2a\xi }Ff, f)\).

II. Let \(\{g_n\}\) be an orthonormal basis in \(L_2(\mathbb {R})\) which consists of the eigenfunctions of the anharmonic oscillator

The eigenfunctions \(g_n\) are either even or odd functions.

Consider the sequence \(f_n(x)=e^{p(x)}g_n(x)\), where a real-valued odd function \(p\in {C^2}(\mathbb {R})\) satisfies Assumption II in [14]. The sequence \(\{f_n\}\) is complete in \(L_2(\mathbb {R})\) [14, Lemma 3.6] and \(f_n\) are simple eigenfunctions of the \(\mathcal {P}\)-symmetric operator

The sequence \(\{f_n\}\) is a quasi basis in \(L_2(\mathbb {R})\) (since \(f_n=e^{-Q/2}g_n\) with \(Q=-2p(x)I\)) and H restricted on \(\text{ span }\{f_n\}\) is essentially self-adjoint in the new Hilbert space \((\mathfrak {H}_G, (\cdot ,\cdot )_G)\), where \(\mathfrak {H}_G\) is the completion of \(\text{ span }\{f_n\}\) with respect to the norm: \(\Vert f\Vert ^2_G=(e^Qf,f)=(e^{-2p(x)}f, f)\).

III.An example of a complete J-orthonormal sequence\(\{f_n\}\)which cannot be a quasi-basis. The dual definite subspaces \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}\) and \(\mathfrak {L}_-\) considered in Sect. 4.2.3 cannot be dual quasi maximal for \(1<\delta \le \frac{3}{2}\). Therefore, each J-orthonormal sequence \(\{f_n\}\) such that the closure of its positive/negative elements coincide with \({{\mathfrak {L}}}_+^{max}\) and \(\mathfrak {L}_-\), respectively cannot be a quasi basis.

References

Albeverio, S., Kuzhel, S.: \({\cal{P}}{\cal{T}}\)-symmetric operators in quantum mechanics: Krein spaces methods. In: Bagarello, F., Gazeau, J.-P., Szafraniec, F.H., Znojil, M. (eds.) Non-selfadjoint Operators in Quantum Physics: Mathematical Aspects, Wiley, Hoboken, N.J., pp. 293–343 (2015)

Arlinskiĭ, Y.M., Hassi, S., Sebestyén, Z., de Snoo, H.S.V.: On the class of extremal extensions of a nonnegative operator. In: Recent Advances in Operator Theory and Related Topics the Bela Szokefalvi-Nagy Memorial Volume, Operator Theory: Advances and Applications, Vol. 127. Birkhauser, pp. 41–81 (2001)

Arlinskiĭ, Y.M., Tsekanovskiĭ, E.R.: Quasiselfadjoint contractive extensions of a Hermitian contraction, Teor. Funktsii Funktsional. Anal. i Prilozhen. No. 50, 9–16 (1988). (Russian); translation in J. Soviet Math. 49(6), 1241–1247 (1990)

Arlinskiĭ, Y., Tsekanovskiĭ, E.: M. Krein’s research on semi-bounded operators, its contemporary developments, and applications. Oper. Theory Adv. Appl. 190, 65–112 (2009)

Akhiezer, N.I., Glatzman, I.M.: Theory of Linear Operators in Hilbert Spaces, vol. II. Pitman Publishing, London (1981)

Azizov, T.Y., Iokhvidov, I.S.: Linear Operators in Spaces with Indefinite Metric. Wiley, Chichester (1989)

Bender, C.M.: Making sense of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. Rep. Prog. Phys. 70, 947–1018 (2007)

Bender, C.M.: Introduction to \(\cal{P}\cal{T}\)-symmetric quantum theory. Contemp. Phys. 46, 277–292 (2005)

Bender, C.M., Kuzhel, S.: Unbounded \(\cal{C}\)-symmetries and their nonuniqueness. J. Phys. A 45, 444005–444019 (2012)

Grod, A., Kuzhel, S., Sudilovskaja, V.: On operators of transition in Krein spaces. Opusc. Math. 31, 49–59 (2011)

Krein, M.G.: Theory of self-adjoint extensions of semibounded operators and its applications I. Math. Trans. 20, 431–495 (1947)

Kuzhel, S., Sudilovskaja, V.: Towards theory of \(\cal{C}\)-symmetries. Opusc. Math. 37, 65–80 (2017)

Langer, H.: Maximal dual pairs of invariant subspaces of \(J\)-self-adjoint operators. Math. Zametki 7, 443–447 (1970). (Russian)

Mityagin, B., Siegl, P., Viola, J.: Differential operators admitting various rates of spectral projection growth. J. Funct. Anal. 272, 3129–3175 (2017)

Phillips, R.S.: The extension of dual subspaces invariant under an algebra. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Linear Spaces (Jerusalem, 1960). Jerusalem Academic Press, pp. 366–398 (1961)

Acknowledgements

The first two authors (AK) and (SK) gratefully acknowledge support from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Daniel Aron Alpay.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamuda, A., Kuzhel, S. & Sudilovskaya, V. On Dual Definite Subspaces in Krein Space. Complex Anal. Oper. Theory 13, 1011–1032 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11785-018-0838-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11785-018-0838-x