Abstract

Purpose

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in the US since March 2020 on cancer survivorship among Black and Hispanic breast cancer (BC) survivors remains largely unknown. We aimed to evaluate associations of the pandemic with participant characteristics, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and lifestyle factors among Black and Hispanic BC survivors in the Women’s Circle of Health Follow-Up Study and the New Jersey BC Survivors Study.

Methods

We included 447 Black (npre = 364 and npost = 83) and 182 Hispanic (npre = 102 and npost = 80) BC survivors who completed a home interview approximately 24 months post-diagnosis between 2017 and 2023. The onset of the pandemic was defined as March 2020. The association of the pandemic with binary outcomes was estimated using robust Poisson regression models.

Results

Hispanic and Black BC survivors recruited after the onset of the pandemic reported higher socioeconomic status and fewer comorbidities. Black women in the post-pandemic group reported a higher prevalence of clinically significant sleep disturbance (prevalence ratio (PR) 1.43, 95% CI 1.23, 1.68), lower sleep efficiency, and lower functional well-being, compared to the pre-pandemic group. Hispanic women were less likely to report low health-related quality of life (vs. high; PR 0.62, 95% CI 0.45, 0.85) after the onset of the pandemic.

Conclusions

Ongoing research is crucial to untangle the impact of the pandemic on racial and ethnic minorities participating in cancer survivorship research, as well as PROs and lifestyle factors.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

This study highlights the importance of considering the impact of the pandemic in all aspects of research, including the interpretation of findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

There are limited data on how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and lifestyle factors in breast cancer (BC) survivors of different racial and ethnic groups, particularly after the vaccine became available. Racial and ethnic minoritized populations with cancer are at higher risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalizations, and more adverse outcomes, compared to their White counterparts [1]. Black and Hispanic BC survivors in the United States (US) experience higher prevalence of obesity [2, 3] and comorbidities [3,4,5], which, along with the burden of side effects from BC treatment, have been associated with poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [6], sleep disturbance [7], and higher levels of stress [6,7,8,9]. Moreover, these comorbidities and lifestyle factors have also been identified as important risk factors for increased COVID-19 burden [4, 10] and compound the physical and psychosocial challenges accompanying BC diagnosis and treatment.

Since the US adopted nationwide pandemic restrictions in March 2020, BC survivors have encountered numerous challenges, including treatment delays, limited access to supportive care, changes in therapeutic encounters, and financial constraints [1, 11,12,13,14]. Cancer care disruption may be more pronounced in Black and Hispanic populations, who tend to have lower income occupations and less paid leave for illness given systemic inequities in education and opportunities [12, 15, 16]. Moreover, the pandemic-imposed social distancing restrictions impeded access to vital support networks in these communities. However, taking into account the pronounced cultural importance placed on family and friends within Hispanic and Black women, a favorable trajectory in increased family support during the pandemic could act as an adaptive coping mechanism, enabling these communities to thrive amidst the challenges posed by the ongoing pandemic [17,18,19].

Given racial health inequities exacerbated during the pandemic, identifying differences in participant characteristics and factors associated with resilience in Hispanic and Black BC survivors could inform post-pandemic studies and strategies to progress toward narrowing disparities in BC survivorship. However, existing studies evaluating the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on BC survivors are predominantly in White population [20, 21]. Therefore, this study aimed to compare participant characteristics, PROs (i.e., HRQoL, perceived stress, sleep, and financial toxicity), and lifestyle factors (i.e., obesity, smoking, and alcohol) among Black and Hispanic BC survivors interviewed before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study population and design

We used data from the Women’s Circle of Health Follow-Up Study (WCHFS) [22] and the New Jersey BC Survivors Study (NJBCS) [9, 23], two population-based prospective studies of Black and Hispanic BC survivors in New Jersey. In brief, WCHFS is a longitudinal cohort study of Black BC survivors identified by the New Jersey State Cancer Registry using rapid case ascertainment at 10 counties within the state. Women were eligible to participate if they self-identified as Black or African American, were aged 20–75 years old, had a recent histologically confirmed ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive BC, had no previous history of cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer, and are able to speak and read English. Baseline and follow-up visits were conducted approximately 10 and 24 months after diagnosis via home interviews, respectively. Home visits included collection of anthropometric measures; blood measures; biospecimen collection, following standardized protocols [22]; and computer-assisted interviews to administer questionnaires assessing sociodemographic, reproductive, and lifestyle factors; PROs; and medical history. Further details regarding the design and conduct of WCHFS have been described previously [22]. For lifestyle factors and PROs in the current analysis for WCHFS participants, only data collected at follow-up visit was used.

The NJBCS, initiated in May 2019, followed a generally similar methodology to that used in the WCHFS [9, 23]. Differences from the WCHFS include six target counties in NJ instead of 10 and only one home visit for data collection approximately 12–24 months after diagnosis, mainly due to budget constraints. Hispanic and Black BC survivors proficient in English and/or Spanish were able to participate in the NJBCS. For Spanish-speaking women, validated Spanish versions of questionnaires were used when possible, and other instruments were professionally translated to Spanish. Data collection followed similar protocols to the WCHFS. First, we confirmed eligibility; then, at the home visit, we collected questionnaires using computer-assisted interviews and body measurements. Both study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. All participants provided written informed consent before participating.

We included a total of 447 Black and 182 Hispanic BC survivors who completed a home interview ~ 24 months post-diagnosis, from January 2017 to April 2023, 3 years before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in March 2020. The mean time and SD from diagnosis to interview in the pre- and post-pandemic groups were as follows: pre = 21 months (4.0) and post = 23 months (5.9), for Hispanics, and pre = 26 (3.7) months and post = 23 months (5.9), for Black BC survivors at the follow-up visit in our study. Recruitment of Hispanic and Black BC survivors in the NJBCS was briefly halted due to the unique challenges posed by pandemic restrictions and resumed in December 2020, the same month when the COVID-19 vaccine became available in New Jersey.

Pandemic period

The COVID-19 pandemic era was defined as “pre-” for participants interviewed during the 3 years preceding the start of the pandemic restriction in March 2020 (January 2017–March 2020), and “post-” for those interviewed within the 3 years after the start of the pandemic restrictions (March 2020–April 2023).

Patient-reported outcomes

HRQoL was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast Cancer (FACT-B) instrument, including five subscale scores physical well-being (PWB), social and family well-being (SFWB), emotional well-being (EWB), functional well-being (FWB), and breast cancer–specific scale (BCS), which is available in English and Spanish [24,25,26]. Increased FACT-B and domains scores indicate better HRQoL outcome.

Sleep disturbance was assessed using the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [27], a 19-item scale that assesses seven components of sleep quality over the past month, including sleep quality, latency, duration, efficiency, habitual sleep disturbance, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. A score of ≥ 5 for global sleep disturbance and < 85% for sleep efficiency indicates clinically significant outcomes. Sleep efficiency scores were calculated as the percentage of the time spent in bed that is spent asleep [28, 29].

Perceived stress was assessed using the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale 10 (PSS-10) [30]. The PSS asks questions about the participant’s feelings and thoughts during the last month. Finally, to measure financial burden, respondents were asked “To what degree has cancer caused financial problems for you and your family?” with response options ranging from 1 = a lot to 4 = not at all. For all PRO scores in this sample, the internal reliability was generally adequate at each assessment (pre- and post-pandemic), for both Hispanic and Black women (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70 for all) (Supplementary Table 1).

Lifestyle factors

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using weight and height measurements by trained interviewers using a standardized protocol [22, 31], or from self-report if anthropometric measure was not available, defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). We previously observed high concordance between BMI derived from self-reported weight and height and measured BMI (intraclass correlation = 0.97) [32]. For cigarette smoking, ever smokers were defined as those who reported ever smoking at least one cigarette per day for 1 year. Alcohol consumption since diagnosis was defined based on regular consumption in the year prior to the interview. For drinkers, participants reported information on the type of alcoholic drink (beer, wine, or liquor), the amount, and the frequency consumed. Non-drinkers were defined as those who did not report drinking or drank zero alcoholic beverages per week.

Statistical analysis

We used the chi-squared test for independence to compare the percentages of patients’ sociodemographic characteristics in each pandemic era group. Continuous variables were compared using the independent two-sample t-test.

Multivariable robust Poisson regression models were used to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association of enrollment before or after pandemic restrictions with PROs and lifestyle factors. FACT-B score and domains were dichotomized as high (vs. low) based on the sample median. For continuous FACT-B and domains, clinically significant change in HRQoL was defined as a score difference of 7–8 for total score and 2–3 for domains [33]. Obesity was categorized as BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2. Due to power limitations and to a low prevalence of drinkers reported by this population, alcohol was evaluated as drinking vs. not drinking. Similarly, we evaluated smoking as ever vs. never smoking.

For all models, the covariates of interest considered were age at diagnosis (continuous), educational level (high school or below, some college or higher), annual household income (< $25,000, ≥ $25,000), health insurance (private, Medicare/Medicaid, uninsured/other), marital status (married/living as married, widow/divorced/separated/single), nativity (US-born, foreign-born), menopausal status (pre-menopausal, post-menopausal), comorbidities (i.e., history of hypertension and diabetes). Covariates included in the multivariable models were selected based on stepwise procedure (P value < 0.1).

For Black women, we repeated the analysis among non-Hispanic Black women (n = 437). P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 17.0.

Results

The analytical sample of this population-based study included a total of npre = 102 and npost = 80 Hispanic and npre = 364 and npost = 83 Black BC survivors. The mean (SD) age for Hispanic and Black BC survivors was 53.5 (10.6) years and 56.6 (10.2) years, respectively.

Sociodemographic and lifestyle factors and PROs by the COVID-19 pandemic era: descriptive characteristics and univariate comparison

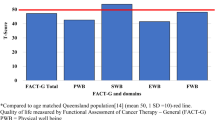

The distribution of relevant sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle factors by the COVID-19 pandemic era is shown in Table 1. When compared to those in the pre-pandemic group, Hispanic women interviewed after the onset of the pandemic were significantly less likely to have been diagnosed with diabetes (pre- vs. post-pandemic: 28% vs. 10%) and to be drinkers (pre- vs. post-pandemic: 43% vs. 19%) (P < 0.05, for all) (Table 1). Hispanic women recruited after the onset of the pandemic reported clinically significant higher overall mean FACT-B score, physical and emotional well-being, and BC symptoms, when compared to the pre- pandemic group (Supplementary Fig. 1).

When compared to the pre-pandemic group, Black BC survivors in the post-pandemic group were significantly more likely to have some college education or higher (pre- vs. post-pandemic: 67% vs. 81%), to be foreign-born (pre- vs. post-pandemic: 15% vs. 29%), and less likely to be diagnosed with hypertension (pre- vs. post-pandemic: 77% vs. 48%) (P < 0.05, for all) (Table 1). Black women in the post-pandemic group reported clinically significant lower functional well-being, when compared to the pre-pandemic group (Supplementary Fig. 2). No clinically significant differences in mean scores were observed for the overall FACT-B score and other domains.

Multivariate comparison of lifestyle factors and PROs pre- and post-pandemic

Results from the multivariable Poisson models indicated that both Hispanic and Black women in the post-pandemic group reported a lower prevalence of moderate to high perceived stress (PRHispanic 0.85, 95% CI 0.77, 0.94 and PR lack 0.91, 95% CI 0.84, 0.99), and a lower prevalence of alcohol consumption (PRHispanic 0.41, 95% CI 0.26, 0.68 and PRBlack 0.71, 95% CI 0.51, 0.98), compared to the pre-pandemic group (Table 2 and 3).

Multivariable adjusted models also indicated that Hispanic BC survivors in the post-pandemic group were less likely to report low HRQoL (FACT-B total score) (vs. high, PR 0.62, 95% CI 0.45, 0.85) compared to the pre-pandemic group. For FACT-B specific domains, Hispanic women were less likely to report low (vs. high) physical and emotional well-being and BC-specific symptoms (PR 0.71, 95% CI 0.53, 0.94; PR 0.70, 95% CI 0.51, 0.95; and PR 0.59 95% CI 0.43, 0.82, respectively) and more likely to report low social well-being (PR1.32, 95% CI 1.09, 1.60), compared to the pre-pandemic group. No other significant differences by pandemic era were observed for other PROs (i.e., functional well-being, sleep disturbance, efficiency and time, and financial toxicity) and lifestyle factors (i.e., obesity and smoking) among Hispanic women (Table 2).

In contrast, Black BC survivors in the post-pandemic group were more likely to report low functional and emotional well-being (PR 1.41, 95% CI 1.18, 1.69 and PR 1.31, 95% CI 1.08, 1.58, respectively) compared to the pre-pandemic group. Black women also reported a 43% and 68% higher prevalence of clinically significant sleep disturbance and poor efficiency (PR 1.43, 95% CI 1.23, 1.68 and PR1.50, 95% CI 1.30, 1.73, respectively), compared to the pre-pandemic group. No other significant differences by pandemic era were observed for other PROs (i.e., FACT-B total score, physical well-being, social well-being, BC-specific scale, and financial toxicity) and lifestyle factors (i.e., obesity and smoking) among Black women (Table 3). Restricting the analysis to non-Hispanic Black participants did not materially change the results.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the potential impact of COVID-19 on participant sociodemographic characteristics, PROs, and lifestyle factors among Hispanic and Black BC survivors in New Jersey. Sociodemographic characteristics and the prevalence of PROs and lifestyle factors varied by pandemic era and race and ethnicity. Hispanic women after the onset of the pandemic reported more favorable overall HRQoL, physical and emotional well-being, and BC symptoms, but lower social well-being, compared to women in the pre-pandemic group. Conversely, Black women in the post-pandemic group had lower functional and emotional well-being, clinically significant sleep disturbance, and lower sleep efficiency compared to the pre-pandemic sample. Hispanic and Black survivors in the post-pandemic group reported lower levels of perceived stress and lower prevalence of alcohol consumption, compared to women in the pre-pandemic group. We also observed important differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of women participating before and after the onset of the pandemic. Hispanic women had lower prevalence of diabetes, while Black women were more educated, were foreign-born, and had a lower prevalence of hypertension, compared to women interviewed before the pandemic. This highlights the possible impact of the pandemic on recruitment in BC survivorship studies and underscores the need of caution in interpreting results.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, our findings revealed higher levels of HRQoL, physical well-being, emotional well-being, and fewer BC-specific symptoms in the Hispanic post-pandemic group compared to the pre-pandemic group. Yet, lower social and family well-being scores were reported. There are some possible explanations to the higher HRQoL reported by Hispanic women recruited after implementation of pandemic restrictions. First, considering the survivors’ prior adaptation to social distancing restrictions and stress due their diagnosis and treatment, it is possible that the pandemic’s additional restrictions might have had a limited impact on their overall HRQoL and emotional well-being. Moreover, Hispanic survivors may have gone through reconceptualization of their HRQoL in relation to their diagnosis, given the experience of such global natural disaster [34, 35]. Longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate these processes. Moreover, familism is a core value within many Hispanic families that have been linked to social support, adaptation [17, 36], and enhanced emotional well-being [37, 38]. However, it is also crucial to recognize that under certain circumstances, familism can inadvertently contribute to negative outcomes [8, 39]. Given the pandemic-induced lack of social proximity to family members and friends during the lockdown, except for those within the same household, it is possible that pre-pandemic poor family values [40] or negative shifts in family dynamics [36, 39] during the pandemic likely contributed to the lower reported social and family well-being in the post-pandemic group. Our results may manifest the complex and diverse effect of family on psychosocial and behavioral outcomes among Hispanic BC survivors [41]. Lastly, these observations could also be a result of self-selection of BC survivors with higher socioeconomic status or fewer comorbidities in the study after the pandemic. Nevertheless, despite the generally higher HRQoL and higher physical, emotional, and BC-specific well-being among Hispanic participants, their overall HRQoL and domain-specific scores remain lower, when compared to Black BC survivors in our study and non-Hispanic White women [8, 42]. These disparities likely stem from multifactorial experiences, including language barriers, access to care, challenges in navigating the healthcare system, and lack of access to culturally and linguistically appropriate clinicians [6, 8].

Additionally, although no significant differences by pandemic era were observed, around 80% and 90% of Hispanic BC survivors reported clinically significant sleep disturbance and low sleep efficiency, which is almost twice the prevalence in the general population [43] and among cancer patients (range 36–69%) [44,45,46]. Our study underscores the critical need for further investigation beyond the pandemic to comprehend and address the needs of Hispanic BC survivors and narrow these disparities in psychosocial factors.

We also observed worse sleep disturbance and lower functional and emotional well-being among Black women in the post-pandemic group compared to those in the pre-pandemic group. Close to 80% of the Black women in the post-pandemic group reported clinically significant sleep disturbance, which is higher than findings from a prior pre-pandemic study using the full cohort of Black BC survivors in the WCHFS (61%) [7] and exceeding those in a pre-pandemic study in predominantly White BC survivors (42%) [47]. Although studies in Black BC survivors post-pandemic are limited, our results are consistent with a population-based study in the general population that observed the greatest prevalence of post-pandemic sleep disturbance in Black women when compared to other racial and ethnic groups [48]. Moreover, in contrast to prior findings from the WCHFS looking at risk factors for sleep disturbance, where an association of education attainment with sleep disturbance was reported [7], in this study, we observed no differences in the association of COVID-19 pandemic with sleep disturbance and efficiency, when stratified by educational attainment, suggesting that the pandemic impact on sleep disturbance outcomes was irrespective of their educational attainment. This result is not surprising given the heightened social injustice and psychosocial burden of the pandemic among underserved populations, particularly among Black women. For instance, a prior study using a large nationally representative sample of US adults demonstrated a significant association between perceived discrimination during the pandemic and poor sleep quality in Black adults, but not in Hispanic and White adults [49]. Quantitative studies examining the impact of perceived discrimination on sleep in cancer survivorship are warranted. Moreover, sleep disturbance is an important functional impairment in cancer survivors [50] and crucial for their HRQoL, aligning with the poor functional and emotional well-being we observed in the post-pandemic group. A recent study using data from the National Health Interview Survey reported an increased trend in low functional limitations in cancer survivors from 1999 to 2018, including sleep disturbance, disproportionately burdening Black and Hispanic cancer survivors [50]. The continuous assessment of sleep and functional status among Black BC survivors in the post-pandemic era is therefore critical to identify underlying factors explaining these associations and ultimately developing targeted interventions for improved long-term survivorship care. For example, culturally targeted mobile health interventions including cognitive behavioral therapies are promising tools for improving sleep quality among Black [51] and Hispanic [52] BC survivors.

This study has important strengths. The majority of quantitative studies comparing PROs and lifestyle factors before and after the pandemic have been performed early in the pandemic [53]. Therefore, this study stands as one of the few studies comparing PROs and cancer-related behaviors before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, using a diverse population-based study of Black and Hispanic BC survivors. Furthermore, to ensure precise measurement of PROs among an important high-risk population, our study utilized scales with validated Spanish translations specifically tailored for Hispanic women.

This study is not without limitations. First, our results are based on cross-sectional comparisons, and therefore, they should be interpreted with caution. The results from this study are based on the population of Black and Hispanic BC survivors in New Jersey. Therefore, the extent to which our findings can be generalized to other geographic areas in the country is uncertain. Nevertheless, within the state of New Jersey, our study sample demonstrates a high level of diversity and represents the broader population of BC patients. Longitudinal follow-up of the Hispanic and Black BC survivors is warranted to reveal PRO and lifestyle changes over time. We were unable to control for the myriad changes in social patterns that followed pandemic restrictions and occurred alongside the restrictions themselves, which may have influenced the population’s desire and willingness to participate in research. We documented differences in sociodemographic characteristics of participants in our study before and after COVID-19. Despite controlling for these factors, residual confounding is possible. Further research is essential for understanding how to increase the participation of racial and ethnic minority cancer survivors in the post-pandemic era and developing strategies to enhance recruitment. The continuously evolving nature of the pandemic, now considered endemic, suggests that ongoing efforts are necessary.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced additional complexities into the lives of BC survivors, and our findings suggest that its potential impact on research participation, PROs, and lifestyle factors may vary among different racial and ethnic groups. Overall HRQoL remained low, and certain PROs, such as sleep disturbance, were common among both Hispanic and Black BC survivors and remained detrimental compared to other cancer survivors and to the general population. These results underscore the significance of more personalized and culturally informed care practices and highlight the need for healthcare providers to enhance and tailor services to effectively address the diverse needs of Black and Hispanic women. For instance, clinicians could consider assessing sleep quality, recognizing it as a prevalent adverse outcome that persisted among both Hispanic and Black BC survivors even after the onset of the pandemic. Moreover, ongoing evaluation of differences in characteristics of individuals participating in research after the pandemic and further along the cancer continuum, including the survivorship period, is crucial for reducing disparities in minoritized and vulnerable populations.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466.

Bandera EV, Maskarinec G, Romieu I, John EM. Racial and ethnic disparities in the impact of obesity on breast cancer risk and survival: a global perspective. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(6):803–19.

Gallagher EJ, LeRoith D, Franco R, Antoniou IM, Nayak A, Livaudais-Toman J, et al. Metabolic syndrome and pre-diabetes contribute to racial disparities in breast cancer outcomes: hypothesis and proposed pathways. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(7):745–53.

Hamaway S, Nwokoma U, Goldberg M, Salifu MO, Saha S, Boursiquot R. Impact of diabetes on COVID-19 patient health outcomes in a vulnerable racial minority community. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(7):e0286252.

Gallagher EJ, Fei K, Feldman SM, Port E, Friedman NB, Boolbol SK, et al. Insulin resistance contributes to racial disparities in breast cancer prognosis in US women. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22(1):40.

Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3(4):212–22.

Gonzalez BD, Eisel SL, Qin B, Llanos AAM, Savard J, Hoogland AI, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and trajectories of sleep disturbance in a cohort of African-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(5):2761–70.

Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(2):191–207.

Bandera EV, Hong C-C, Qin B: Impact of obesity and related factors in breast cancer survivorship among Hispanic women. Advancing the science of cancer in Latinos: building collaboration for action. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 163–76.

Mahamat-Saleh Y, Fiolet T, Rebeaud ME, Mulot M, Guihur A, El Fatouhi D, et al. Diabetes, hypertension, body mass index, smoking and COVID-19-related mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e052777.

Kumar D, Dey T. Treatment delays in oncology patients during COVID-19 pandemic: a perspective. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):010367.

Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1891.

Llanos AA, Ashrafi A, Ghosh N, Tsui J, Lin Y, Fong AJ, et al. Evaluation of inequities in cancer treatment delay or discontinuation following SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(1):e2251165-e.

Zhao F, Henderson TO, Cipriano TM, Copley BL, Liu M, Burra R, et al. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on the quality of life and treatment disruption of patients with breast cancer in a multiethnic cohort. Cancer. 2021;127(21):4072–80.

Small SF, van der Meulen Rodgers Y, Perry T: Immigrant women and the covid-19 pandemic: an intersectional analysis of frontline occupational crowding in the United States, Forum for Social Economics. Taylor & Francis; 2023. p 1–26.

Klugman M, Patil S, Gany F, Blinder V. Vulnerabilities in workplace features for essential workers with breast cancer: implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. Work. 2022;71(4):815–23.

Isasi CR, Gallo LC, Cai J, Gellman MD, Xie W, Heiss G, et al. Economic and psychosocial impact of COVID-19 in the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Health equity. 2023;7(1):206–15.

Le T-A. The relationship between familism and social distancing behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Electronic Theses and Dissertations; 2020. p. 374. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/374

Hamilton JB, Abiri AN, Nicolas CA, Gyan K, Chandler RD, Worthy VC, et al. African American women breast cancer survivors: coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. J Cancer Educ. 2023;38(5):1539–47.

Bargon CA, Mink van der Molen DR, Batenburg MC, van Stam LE, van Dam IE, Baas IO, et al. Physical and mental health of breast cancer patients and survivors before and during successive SARS-CoV-2-infection waves. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:2375–390

Llanos AAM, Fong AJ, Ghosh N, Devine KA, O’Malley D, Paddock LE, et al. COVID-19 perceptions, impacts, and experiences: a cross-sectional analysis among New Jersey cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2024;18(2):439–49.

Bandera EV, Demissie K, Qin B, Llanos AAM, Lin Y, Xu B, et al. The Women’s Circle of Health Follow-Up Study: a population-based longitudinal study of Black breast cancer survivors in New Jersey. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(3):331–46.

Echeverri-Herrera S, Nowels MA, Qin B, Grafova IB, Zeinomar N, Chanumolu D, et al. Spirituality and financial toxicity among Hispanic breast cancer survivors in New Jersey. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(12):9735–41.

Belmonte Martinez R, GarinBoronat O, Segura Badia M, SanzLatiesas J, Marco Navarro E, Ferrer Fores M. [Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Questionnaire for Breast Cancer (FACT-B+4)]. Spanish version validation Med Clin (Barc). 2011;137(15):685–8.

Augustovski FA, Lewin G, Garcia-Elorrio E, Rubinstein A. The Argentine-Spanish SF-36 Health Survey was successfully validated for local outcome research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(12):1279-84 e6.

Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):974–86.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

Levenson JC, Troxel WM, Begley A, Hall M, Germain A, Monk TH, et al. A quantitative approach to distinguishing older adults with insomnia from good sleeper controls. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(2):125–31.

Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Taylor DJ, Bush AJ, Riedel BW. Quantitative criteria for insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(4):427–45.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96.

Bandera EV, Chandran U, Zirpoli G, Gong Z, McCann SE, Hong CC, et al. Body fatness and breast cancer risk in women of African ancestry. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:475.

Qin B, Llanos AAM, Lin Y, Szamreta EA, Plascak JJ, Oh H, et al. Validity of self-reported weight, height, and body mass index among African American breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(4):460–8.

Eton DT, Cella D, Yost KJ, Yount SE, Peterman AH, Neuberg DS, et al. A combination of distribution- and anchor-based approaches determined minimally important differences (MIDs) for four endpoints in a breast cancer scale. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(9):898–910.

Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(11):1507–15.

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. TARGET ARTICLE: “Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence.” Psychol Inq. 2004;15(1):1–18.

Volpert-Esmond HI, Marquez ED, Camacho AA. Family relationships and familism among Mexican Americans on the US–Mexico border during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2023;29(2):145.

Katiria Perez G, Cruess D. The impact of familism on physical and mental health among Hispanics in the United States. Health Psychol Rev. 2014;8(1):95–127.

Corona K, Campos B, Chen C. Familism is associated with psychological well-being and physical health: main effects and stress-buffering effects. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2017;39(1):46–65.

Cahill KM, Updegraff KA, Causadias JM, Korous KM. Familism values and adjustment among Hispanic/Latino individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2021;147(9):947.

Levine EG, Yoo G, Aviv C. Predictors of quality of life among ethnically diverse breast cancer survivors. Appl Res Qual Life. 2017;12(1):1–16.

Geiss C, Chavez MN, Oswald LB, Ketcher D, Reblin M, Bandera EV, et al. “I beat cancer to feel sick:” qualitative experiences of sleep disturbance in black breast cancer survivors and recommendations for culturally targeted sleep interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2022;56(11):1110–5.

Samuel CA, Mbah OM, Elkins W, Pinheiro LC, Szymeczek MA, Padilla N, et al. Calidad de Vida: a systematic review of quality of life in Latino cancer survivors in the USA. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(10):2615–30.

Blumel JE, Cano A, Mezones-Holguin E, Baron G, Bencosme A, Benitez Z, et al. A multinational study of sleep disorders during female mid-life. Maturitas. 2012;72(4):359–66.

Ho RT, Fong TC. Factor structure of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in breast cancer patients. Sleep Med. 2014;15(5):565–9.

Enderlin CA, Coleman EA, Cole C, Richards KC, Kennedy RL, Goodwin JA, et al. Subjective sleep quality, objective sleep characteristics, insomnia symptom severity, and daytime sleepiness in women aged 50 and older with nonmetastatic breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38(4):E314–25.

Chen D, Yin Z, Fang B. Measurements and status of sleep quality in patients with cancers. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):405–14.

Savard J, Ivers H, Villa J, Caplette-Gingras A, Morin CM. Natural course of insomnia comorbid with cancer: an 18-month longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3580–6.

Gaston SA, Strassle PD, Alhasan DM, Pérez-Stable EJ, Nápoles AM, Jackson CL. Financial hardship, sleep disturbances, and their relationship among men and women in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Health. 2023;9(4):551–9.

Niu L, Zhang D, Shi L, Han X, Chen Z, Chen L, et al. Racial discrimination and sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the Health, Ethnicity, and Pandemic (HEAP) Study. J Urban Health. 2023;100(3):431–5.

Patel VR, Hussaini SMQ, Blaes AH, Morgans AK, Haynes AB, Adamson AS, et al. Trends in the prevalence of functional limitations among US cancer survivors, 1999–2018. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(7):1001–3.

Zhou ES, Ritterband LM, Bethea TN, Robles YP, Heeren TC, Rosenberg L. Effect of culturally tailored, internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in black women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. 2022;79(6):538–49.

Oswald LB, Morales-Cruz J, Eisel SL, Del Rio J, Hoogland AI, Ortiz-Rosado V, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of eHealth cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia among Spanish-speaking breast cancer survivors. J Behav Med. 2022;45(3):503–8.

Myers C, Bennett K, Cahir C. Breast cancer care amidst a pandemic: a scoping review to understand the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on health services and health outcomes. Int J Qual Health Care. 2023;35(3).

Acknowledgements

We are sincerely grateful to all the participants and research team members in the Women’s Circle of Health Follow-Up Study and the New Jersey Breast Cancer Study at Rutgers University, the New Jersey State Cancer Registry, and Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA185623, P30CA072720-5929), the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research (COCR23PDF029), and the American Cancer Society (RSG-23–1143513-01-CTPS). This research was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Outcomes Data Support (CPODS) Shared Resource. The New Jersey State Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology Services, New Jersey Department of Health, is funded by the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute under contract 75N91021D00009; the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR); and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under grant NU58DP007117 as well as the State of New Jersey and the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design were performed by B.Q., E.V.B., and C.S.D. C.S.D wrote the first draft for the main manuscript text, tables, and figures. All authors commented and contributed on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Bandera reported receiving personal fees from Pfizer Inc outside the submitted work. Dr. Gonzalez reported fees unrelated to this work from Sure Med Compliance and Elly Health. No other conflicts were reported.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez-Díaz, C.T., Zeinomar, N., Iyer, H.S. et al. Comparing patient-reported outcomes and lifestyle factors before and after the COVID-19 pandemic among Black and Hispanic breast cancer survivors in New Jersey. J Cancer Surviv (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01575-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01575-6