Abstract

Purpose

Adequate access to and utilization of preventive services are vital among cancer survivors. This study examined preventive service utilization of cancer survivors compared to matched patients with no history of cancer among patients seeking care at community health centers (CHCs).

Methods

We utilized electronic health record data from the OCHIN network between 2014 and 2017. Cancer survivors (N = 20,538) ages ≥ 18 years were propensity score matched to three individuals with no history of cancer (N = 61,617) by age, sex, region, urban/rural, ethnicity, race, BMI, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Preventive screenings included cancer, mental health and substance abuse, cardiovascular, and infectious disease screenings, and vaccinations. Patient-level preventive service indices were calculated for each screening as the total person-time covered divided by the total person-time eligible. Preventive service rate ratios comparing cancer survivors to patients with no history of cancer were estimated using negative binomial regression.

Results

Cancer survivors had higher overall preventive service utilization (incidence rate ratio = 1.11, 95% confidence interval = 1.09–1.13) and higher rates of cancer screenings (IRR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.12–1.20). There was no difference between the two groups in mental health screenings.

Conclusions

Cancer survivors were more likely to be up-to-date with preventive care than their matched counterparts. However, mental health and substance abuse screenings were low in both groups, despite reports of increased mental health conditions among cancer survivors.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

With the growing number of cancer survivors in the USA, efforts are needed to ensure their access to and utilization of preventive services, especially related to behavioral and mental healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There are currently nearly 17 million cancer survivors in the USA, with that number expected to increase to over 22 million by 2030 [1]. The majority of these cancer survivors (67%) have survived more than 5 years. As cancer survivors are at an increased risk for many of the chronic conditions, it is vital that survivors receive appropriate preventive care. Preventive services can save lives and decrease healthcare costs by identifying illnesses earlier, managing them more effectively, and treating them before they develop into complicated, debilitating conditions [2, 3]. However, the focus of cancer survivors is likely on receiving cancer care over appropriate non-cancer–related preventive services such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease screenings. Studies examining preventive service use of cancer survivors show mixed results [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Cancer survivors have been observed to be more likely to have cancer screenings (e.g., mammograms, colorectal cancer screening, prostate-specific antigen test), but less likely to have non-cancer preventive screenings (e.g., influenza vaccination, cholesterol screening) [4,5,6].

Differences have been found with access to preventive services for cancer survivors ages 18–64 with private health insurance when compared to those with public insurance or no insurance [16]. Cancer survivors who are not able to continue working full-time may become eligible for Medicaid during cancer treatment due to lost wages, but may not be able to maintain Medicaid coverage after cancer treatment [17]. There has been no study on preventive service utilization among cancer survivors seen in community health centers (CHCs), which predominantly serve publicly insured or uninsured patients. Most previous studies focused on older populations using SEER Medicare data and/or only examining a specific cancer.

The aim of this study was to compare receipt of 14 cancer and non-cancer preventive services between cancer survivors and matched patients with no history of cancer in a network of CHCs across 14 states. We hypothesized that cancer survivors would have higher receipt of cancer screenings and similar receipt of non-cancer screenings than patients with no history of cancer.

Methods

We utilized electronic health record (EHR) data from the OCHIN practice-based research network. All clinics within OCHIN use the same instance of Epic® EHR, which is centrally housed and managed at OCHIN. There are more than 350 OCHIN clinics located in 14 states across the USA with more than 2 million patients. We studied preventive service utilization between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2017.

Patients were eligible for the study if they had an ambulatory visit within the OCHIN network in 2 years prior to the study period (2012–2013) to ensure they were established patients within OCHIN. Patients had to be 18 or older at the beginning of the study period (January 1, 2014) and had to have an ambulatory visit within the study period. Cancer survivors were included if they were diagnosed with cancer before the start of the study period with a malignant cancer. Cancer survivors were identified through diagnosis codes and problem lists within their medical records. Patients that were not alive at the end of 2017 were excluded.

Preventive services outcome measures

The primary outcomes of the study were preventive screening indices. Preventive screening indices were calculated as rates where the numerator was the total person-time covered and the denominator was total person-time eligible [18]. This calculation results in a percentage of time “covered” by a preventive service (e.g., a mammogram “covers” an individual for breast cancer screening for 2 years). Therefore, by definition, each index was a number between 0 and 1: 0 being never received screenings and 1 being always covered (or on-time). Eligibility for each screening was determined using A or B recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Service Task Force. Supplemental Table 1 shows all the criteria used for each preventive service [18]. Individual preventive service indices were constructed for cancer screenings (breast, cervical, colorectal cancer screenings, and HPV vaccine), mental health and substance abuse screenings, cardiovascular screenings (blood pressure, HbA1c, and lipid screenings), and infectious disease screening and vaccination (chlamydia and hepatitis C screening, flu, and pneumonia vaccines). Additionally, an overall preventive service index was estimated averaging across all services combined to provide a comprehensive measure of overall preventive utilization [18].

Statistical analysis

Each cancer survivor was propensity score matched with replacement to three patients with no history of cancer on age at the beginning of the study period, sex, urban/rural, ethnicity, race, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and body mass index (BMI). For the sub-analyses with specific cancer survivors (breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung), the cancer survivors were re-matched with propensity scores to ensure sex and age eligibility were appropriately matched upon.

For each preventive service index, we compared average receipt between cancer survivors and patients with no history of cancer and evaluated differences using standardized mean differences (SMD). The two groups are significantly different when the absolute value of the standardized mean differences is larger than 0.1. Given that some differences in patient characteristics between those with and without cancer were observed, and to account for overdispersion of patients with 0 as their preventive service index score, we utilized mixed effects negative binomial regression to estimate preventive service rate ratios comparing cancer survivors to patients with no history of cancer. Models utilized clinic random intercepts to account for clustering of patients within clinics. Models were run for each preventive service index for all cancer survivors combined compared to individuals with no history of cancer. Models were also run for each group of individual cancer survivors: breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung. All models controlled for age, insurance status, smoking status, body mass index, race, ethnicity, urban/rural, and number of visits during the study period [19]. These adjustments account for residual imbalance between the groups after propensity score matching. All analyses were completed in SAS 9.4.

Results

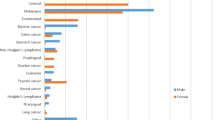

There were 21,538 cancer survivors in the study population matched to 61,617 patients with no history of cancer. Cancer survivors were more likely to be male and non-White, have insurance, and be a former smoker (Table 1). Comparisons between breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer survivors and their propensity score matched patients with no history of cancer are shown in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Across all cancers, cancer survivors had more visits on average than cancer-free individuals (mean = 13.1, vs mean = 8.1, SMD = 0.3).

Cancer survivors had a higher overall preventive service index than individuals with no history of cancer (mean = 38.4 vs mean = 34.4, SMD = 0.16), as seen in Table 2. Of the combined indices, all had an absolute value SMD of at least 0.1 with cancer screenings having the largest gap between cancer survivors and individuals with no history of cancer (SMD = 0.19).

Cancer survivors had a significantly higher overall preventive index score (incidence rate ratio = 1.11, 95% confidence interval = 1.09–1.13; Table 3). Cancer survivors had a 16% increased rate of cancer screenings compared to individuals with no history of cancer, with a 22% increased rate of colorectal cancer screenings. While cancer survivors appear to receive increased cancer, cardiovascular, and infectious disease preventive services, there was no significant difference for mental health and substance abuse index scores between the two groups (IRR = 1.02, 95%CI = 0.99–1.05).

Of the four individual cancer subgroups, breast cancer survivors had the highest IRR for overall preventive index score (IRR = 1.22, 95%CI = 1.16–1.27; Table 3). Prostate cancer survivors also had a significant overall preventive index score (IRR = 1.11, 95%CI = 1.03–1.17). Colorectal cancer survivors also had higher cancer preventive index score (IRR = 1.30, 95%CI = 1.15–1.48) and colorectal cancer surveillance ratio (IRR = 1.39, 95%CI = 1.19–1.63). Lung cancer survivors had a significantly lower rate for the overall preventive index (IRR = 0.80, 95%CI = 0.71–0.90). This decreased rate was also observed in the cardiovascular preventive index score (IRR = 0.85, 95%CI = 0.79–0.92) and the mental health and substance abuse index score (IRR = 0.75, 95%CI = 0.64–0.88).

Discussion

We examined the preventive service utilization of cancer survivors and patients with no history of cancer in CHCs. Overall, cancer survivors had better rates of preventive service utilization when compared to individuals with no history of cancer, except for mental health and substance abuse services. Additionally, differences by cancer types were observed. Breast and prostate cancer survivors generally had better preventive services scores than patients with no history of cancer, while colorectal cancer survivors had similar rates of preventive services, and lung cancer survivors had significantly poorer preventive services rates. In addition, breast and colorectal cancer survivors are recommended to receive mammograms and colonoscopies, respectively, at increased frequency for surveillance and this likely impacted their increased preventive service indexes for cancer screenings. Breast cancer survivors also had increased cervical and colorectal cancer screenings when compared to those with no history of cancer; however, colorectal cancer survivors did not have increased breast and cervical cancer screenings.

Rates of receipt of mental health and substance abuse preventive services did not differ between cancer survivor and patients with no history of cancer. Cancer survivors have been observed to have increased rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide risk, including being more than twice as likely to have disabling psychological problems as adults without a previous cancer diagnosis [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Overall, less than a quarter of cancer survivors were screened for depression or substance abuse. These screenings were also low for the patients with no history of cancer. Low prevalence of mental and behavioral screenings is worrisome as mental disorders are associated with increased risk of a wide range of physical conditions such as heart disease and diabetes [26]. This is especially imperative as cancer survivors are already at an increased risk for these conditions [27, 28]. Mixed methods research is needed to understand the provider- and patient-related barriers to screening for mental health substance abuse.

Lung cancer has the lowest 5-year survival rate (19%) of any of the cancers, while breast and prostate have 5-year survival rates over 90% [1]. The poor survival rate likely explains why lung cancer survivors had significantly lower rates of preventive service utilization compared to those with no history of cancer. For these patients, the focus is likely on cancer survival over receiving screenings for other health conditions.

Our study has several limitations. First, the use of medical records may have led to an underestimation of preventive service utilization. Although the completeness of OCHIN’s preventive service utilization records has been previously validated [29], patients may have received care elsewhere and these records may not always be available in the CHC medical records. In addition, we may have patients who are lost to follow-up which is unaccounted for in this analysis. However, evidence suggests that 80% of established CHC patients, especially with chronic conditions, return for at least one visit in a 3-year period [30]. Second, due to identifying cancer survivors with diagnosis codes and problem lists and only moderate agreement between CHC EHRs and cancer registries, dates of cancer diagnosis were not always available and some cancer survivors were likely not identified [31].

This study also has several strengths. First, the study population comes from 14 states across the USA, which allows for generalizability among CHC patients. Second, this study has over 20,000 cancer survivors, which allowed us not only to study cancer survivors in general but also to have enough power to examine four specific groups of cancer survivors. Third, we were also able to study many different preventive services to get a clearer picture of what types of preventive services cancer survivors are utilizing and where improvement is needed.

In conclusion, cancer survivors overall are more up-to-date with preventive services than individuals with no history of cancer, especially for breast and prostate cancer survivors, but lack screening for mental health and substance abuse. Future directions should focus on understanding the facilitators and barriers to preventive services and on developing interventions to promote and facilitate all preventive services use and delivery in CHCs settings.

Data availability

Data available upon reasonable request.

Change history

21 September 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01108-5

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer treatment & survivorship facts & figures 2019–2021. Atlanta: 2019.

Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Flottemesch TJ, Edwards NM, Solberg LI. Greater use of preventive services in U.S. health care could save lives at little or no cost. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2010;29(9):1656–60. Epub 2010/09/08. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0701.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Preventive services covered by private health plans under the Affordable Care Act. Kasier Family Foundation, 2015.

Trask PC, Rabin C, Rogers ML, Whiteley J, Nash J, Frierson G, et al. Cancer screening practices among cancer survivors. American journal of preventive medicine. 2005;28(4):351–6. Epub 2005/04/16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.005.

Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101(8):1712–9. Epub 2004/09/24. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20560.

Snyder CF, Frick KD, Peairs KS, Kantsiper ME, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, et al. Comparing care for breast cancer survivors to non-cancer controls: a five-year longitudinal study. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24(4):469–74. Epub 2009/01/22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-0903-2.

Earle CC, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Weeks JC. Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast cancer survivors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(8):1447–51. Epub 2003/04/17. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2003.03.060.

Mayer DK, Terrin NC, Menon U, Kreps GL, McCance K, Parsons SK, et al. Screening practices in cancer survivors. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2007;1(1):17–26. Epub 2008/07/24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-007-0007-0.

Duffy CM, Clark MA, Allsworth JE. Health maintenance and screening in breast cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer detection and prevention. 2006;30(1):52–7. Epub 2006/02/04. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdp.2005.06.012.

Wallner LP, Slezak JM, Loo RK, Bastani R, Jacobsen SJ. Ten-year trends in preventive service use before and after prostate cancer diagnosis: a comparison with noncancer controls. The Permanente journal. 2017;21. Epub 2017/10/17. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/16-184.

Martin JY, Schiff MA, Weiss NS, Urban RR. Racial disparities in the utilization of preventive health services among older women with early-stage endometrial cancer enrolled in Medicare. Cancer medicine. 2017;6(9):2153–63. Epub 2017/08/05. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1141.

Lowenstein LM, Ouellet JA, Dale W, Fan L, Gupta Mohile S. Preventive care in older cancer survivors. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2015;6(2):85–92. Epub 2014/12/31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2014.12.003.

Wallner LP, Slezak JM, Quinn VP, Loo RK, Schottinger JE, Bastani R, et al. Quality of preventive care before and after prostate cancer diagnosis. J Men’s Health. 2015;11(5):14–21 (Epub 2015/10/03).

Homan SG, Kayani N, Yun S. Risk Factors, Preventive Practices, and health care among breast cancer survivors, United States, 2010. Preventing chronic disease. 2016;13:E09. Epub 2016/01/23. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.150377.

Lafata JE, Salloum RG, Fishman PA, Ritzwoller DP, O'Keeffe-Rosetti MC, Hornbrook MC. Preventive care receipt and office visit use among breast and colorectal cancer survivors relative to age- and gender-matched cancer-free controls. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2015;9(2):201–7. Epub 2014/09/26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0401-3.

Robin Yabroff K, Short PF, Machlin S, Dowling E, Rozjabek H, Li C, et al. Access to preventive health care for cancer survivors. American journal of preventive medicine. 2013;45(3):304–12. Epub 2013/08/21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.04.021.

The Kaiser Family Foundation, American Cancer Society Spending to survive: cancer patients confront holes in the health insurance system. 2009.

Hatch BA, Tillotson CJ, Huguet N, Hoopes MJ, Marino M, DeVoe JE. Use of a preventive index to examine clinic-level factors associated with delivery of preventive care. American journal of preventive medicine. 2019;57(2):241–9. Epub 2019/07/22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.016.

Nguyen T-L, Collins GS, Spence J, Daurès J-P, Devereaux PJ, Landais P, et al. Double-adjustment in propensity score matching analysis: choosing a threshold for considering residual imbalance. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):78-. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0338-0.

Nathan PC, Nachman A, Sutradhar R, Kurdyak P, Pole JD, Lau C, et al. Adverse mental health outcomes in a population-based cohort of survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(9):2045–57. Epub 2018/02/23. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31279.

Friend AJ, Feltbower RG, Hughes EJ, Dye KP, Glaser AW. Mental health of long-term survivors of childhood and young adult cancer: a systematic review. International journal of cancer. 2018;143(6):1279–86. Epub 2018/02/23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31337.

Mosher CE, Winger JG, Given BA, Helft PR, O'Neil BH. Mental health outcomes during colorectal cancer survivorship: a review of the literature. Psycho-oncology. 2016;25(11):1261–70. Epub 2016/11/05. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3954.

Martinez MR, Pasha A. Prioritizing mental health research in cancer patients and survivors. AMA journal of ethics. 2017;19(5):486–92. Epub 2017/05/30. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.5.msoc2-1705.

Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2003;58(1):82–91. Epub 2003/02/01. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82.

Carreira H, Williams R, Müller M, Harewood R, Stanway S, Bhaskaran K. Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(12):1311–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy177.

Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73(2):150–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688.

Soisson S, Ganz PA, Gaffney D, Rowe K, Snyder J, Wan Y, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes among endometrial cancer survivors in a large, population-based cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018. Epub 2018/05/10. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy070.

Blackburn BE, Ganz PA, Rowe K, Snyder J, Wan Y, Deshmukh V, et al. Aging-related disease risks among young thyroid cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention : A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2017;26(12):1695–704. Epub 2017/11/24. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-17-0623.

Devoe JE, Gold R, McIntire P, Puro J, Chauvie S, Gallia CA. Electronic health records vs Medicaid claims: completeness of diabetes preventive care data in community health centers. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(4):351–8. Epub 2011/07/13. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1279.

Huguet N, Kaufmann J, O'Malley J, Angier H, Hoopes M, DeVoe JE, et al. Using electronic health records in longitudinal studies: estimating patient attrition. Med Care. 2020;58 Suppl 6 Suppl 1(Suppl 6 1):S46-s52. Epub 2020/05/16. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0000000000001298.

Hoopes M, Voss R, Angier H, Marino M, Schmidt T, DeVoe JE, et al. Assessing cancer history accuracy in primary care electronic health records through cancer registry linkage. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020. Epub 2020/12/31. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa210.

Acknowledgements

The authors also acknowledge the participation of our partnering health systems. The views presented in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant number R01CA204267. This work was also supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) under award P50CA244289. This program was launched by NCI as part of the Cancer Moonshot.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BB provided conceptualization, analysis, and writing (original draft). MM provided methodology, visualization, and writing (review and editing). TS provided data curation, analysis, and writing (review and editing). JH provided conceptualization and writing (review and editing). BH provided conceptualization and writing (review and editing). JD provided funding acquisition, conceptualization, supervision, and writing (review and editing). LM provided review and editing. NH provided conceptualization, supervision, and writing (review and editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethic approval

This was approved by Oregon Health & Science University’s Institutional Review Board.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original article has been revised due to retrospective OA order

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blackburn, B.E., Marino, M., Schmidt, T. et al. Preventive service utilization among low-income cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 16, 1047–1054 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01095-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01095-7