Abstract

Purpose

Recent research demonstrated that fear of progression (FoP) is a major burden for adult cancer survivors. However, knowledge on FoP in parents of childhood cancer survivors is scarce. This study aimed to determine the proportion of parents who show dysfunctional levels of FoP, to investigate gender differences, and to examine factors associated with FoP in mothers and fathers.

Methods

Five hundred sixteen parents of pediatric cancer survivors (aged 0–17 years at diagnosis of leukemia or central nervous system (CNS) tumor) were consecutively recruited after the end of intensive cancer treatment. We conducted hierarchical multiple regression analyses for mothers and fathers and integrated parent-, patient-, and family-related factors in the models.

Results

Significantly more mothers (54%) than fathers (41%) suffered from dysfunctional levels of FoP. Maternal FoP was significantly associated with depression, a medical coping style, a child diagnosed with a CNS tumor in comparison to leukemia, and lower family functioning (adjusted R2 = .30, p < .001). Paternal FoP was significantly associated with a lower level of education, depression, a family coping style, a child diagnosed with a CNS tumor in comparison to leukemia, and fewer siblings (adjusted R2 = .48, p < .001).

Conclusions

FoP represents a great burden for parents of pediatric cancer survivors. We identified associated factors of parental FoP. Some of these factors can be targeted by health care professionals within psychosocial interventions and others can provide an indication for an increased risk for higher levels of FoP.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Psychosocial support targeting FoP in parents of childhood cancer survivors is highly indicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

More than 2000 children and adolescents in Germany under 18 years of age are diagnosed with cancer each year [1]. With a 15-year survival rate of approximately 80%, the population of childhood cancer survivors and their families is growing [1, 2]. Even though most parents adapt well after the end of their child’s cancer treatment [3, 4], some parents have to deal with long-term psychosocial burden (e.g., depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress) [3,4,5,6]. Whereas fear of progression (FoP), also referred to as fear of relapse or fear of cancer recurrence, in adult cancer patients has been intensively researched in the last decades [7, 8], only little is known about FoP in parents of childhood cancer survivors. FoP and fear of cancer recurrence or fear of relapse are distinct yet related constructs that share relevant aspects. FoP is defined as the “fear that the illness will progress with all its biopsychosocial consequences, or that it will recur” [9]. It describes a rationally explainable emotional response to a potentially life-threatening disease and is a generic concept of illness-related fears that is applicable on various chronic diseases with different courses (e.g., progression, recurrence) [9]. Therefore, we decided to use the term FoP in this study. FoP does not only concern the survivor, but also their caregivers [10, 11]. A study on FoP in adult cancer survivors and their caregivers found that caregivers reported even higher levels of FoP than survivors [11]. According to recent expert online survey in Germany, health care professionals frequently perceive parental FoP in their clinical practice [12]. Nevertheless, over a long period only qualitative studies described the phenomenon of parental FoP [4, 13,14,15,16,17]. Initial quantitative studies displayed that parental FoP seems to be associated with a low quality of life (QoL), depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress [18,19,20]. Previous studies delivered inconsistent results on associated factors of parental FoP. A study on parents of childhood cancer patients and long-term survivors found significantly negative correlations of FoP with time since diagnosis, parental age, current medical condition of the ill child, number of siblings, and parental anxiety coping skills [19]. This study did not reveal any significant gender differences in FoP levels of mothers and fathers and did not find a significant association between parental FoP and the child’s age at diagnosis [19]. The authors additionally calculated a multiple regression analysis and found significant associations of the child’s current medical condition and the parent’s anxiety coping skills with parental FoP [19]. Another study on parents of children with hematological cancer also did not find gender differences in FoP levels, but they also did not find an association with the time since diagnosis [21]. A recent study on fear of recurrence in adult couples with cancer displayed that male caregivers of women with cancer show higher levels of fear of cancer recurrence than female caregivers [22]. However, female cancer patients reported significantly higher levels of fear of cancer recurrence than male cancer patients.

Overall, little is known about FoP in parents of childhood cancer patients. Due to the small number of studies and the divergent results available, knowledge on factors associated with FoP in parents of childhood cancer survivors is scarce. The identification of associated factors could help health care professionals to identify parents at risk for suffering from dysfunctional levels of FoP. Furthermore, associated factors, for instance gender differences or differences between diagnosis groups with a different risk of progression [1], could provide approaches for targeted interventions and prevention strategies. Moreover, examining parental FoP is particularly relevant since it may also affect the child’s anxiety and distress [23]. This study aimed to determine the proportion of parents who show a dysfunctional level of FoP and to examine associated factors of FoP in mothers and fathers of childhood cancer survivors. Due to the limited data available, the choice of potentially associated factors of FoP follows a rather explorative approach and is based on the literature on FoP in adult patients and caregivers and our clinical experience [11, 22, 24, 25]. The research questions (RQ) are:

-

RQ 1: What is the proportion of mothers and fathers of childhood cancer survivors who show a dysfunctional level of FoP?

-

RQ 2: Are mothers or fathers prone to showing dysfunctional levels of FoP?

-

RQ 3: Which parent-, patient-, and family-related factors are associated with FoP in mothers and fathers?

Methods

Design

This cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study is part of a prospective observational study with a longitudinal mixed-methods design. The overall study has been described in a study protocol [26].

Participants and procedure

In this study, we focus on the most frequent pediatric cancers in Germany, leukemia and central nervous system (CNS) tumors [1]. We included biological parents and other caregivers of children under the age of 18 years at time of diagnosis. Parents were recruited after the end of intensive cancer treatment (e.g., radiation therapy, chemotherapy, surgery). At that point in time, patients in the German health care system switch into aftercare regardless of whether they receive maintenance treatment or not. Exclusion criteria were assessed by the health care providers in the clinics and included physical and/or mental burden (clinical decision by health care providers, applicable if the study participation would be overly burdensome), cognitive limitations, insufficient German language skills, and no interest. We consecutively recruited parents in Germany from July 2016 to March 2019 in two settings: (1) Study registries (International HIT-MED Registry, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02417324; COALL 08-09 study, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01228331; SIOP-LGG 2004 study, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00276640) informed the patients’ clinic after the end of intensive cancer treatment about the study. Health care providers in the clinics informed the parents about the study and provided a consent form to contact the family. If the family gave their consent to be contacted, the research institute sent the study material (written information, consent forms for study participation, and questionnaires) to the parents. (2) Our cooperating rehabilitation clinic informed the families at the beginning of an inpatient rehabilitation program about the study, obtained informed consent, and provided the study material to the families. Detailed information on the recruitment process is provided in the study protocol [26].

Measures

Sociodemographic and medical data

Parents reported sociodemographic and medical information via questionnaire. Depending on the recruitment path, the diagnosis and time since diagnosis were extracted either from the parent’s report or the physician’s report in the rehabilitation clinic.

Fear of progression

FoP was measured with the 12-item Fear of Progression Questionnaire for the parental perspective (FoP-Q-SF/PR) [19]. The FoP-Q-SF/PR is an adaptation of the FoP-Q-SF for adult patients [27]. Parents report on a 5-point Likert scale from never (1) to very often (5) to which extent they feel burdened by aspects of FoP (e.g., I am concerned that my child will have to rely on outside help in everyday life). The FoP-Q-SF/PR allows the calculation of a sum score with higher scores indicating a higher level of FoP. Herschbach et al. [28] suggested a cut-off of ≥ 34 to differentiate functional from dysfunctional levels of FoP. The authors investigated a sample of adult cancer patients using the FoP-Q-SF and calculated the median score (Md = 34). In a second step, they stratified the sample according to their self-reported need for treatment and found a high degree of alignment [28]. This cut-off has also been used in an earlier study on FoP in parents of childhood cancer patients [21]. The FoP-Q-SF/PR has proved to be reliable and valid [18, 19]. Cronbach’s alpha was .86 in our sample.

Quality of life

Parental QoL was measured with The Ulm Quality of Life Inventory for Parents (ULQIE) [29]. The 29 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from never (0) to always (4). The ULQIE enables the calculation of both a total score and five subscale scores (functioning, satisfaction with family situation, emotional distress, self-development, and general well-being) with higher scores indicating a higher QoL. In this study, we used the total score. The ULQIE has adequate psychometric properties [29]. Cronbach’s alpha for the global scale was .93 in our sample.

Additionally, we used the 4-item physical well-being subscale of the KINDL-R [30, 31]. The KINDL-R was designed to assess children’s health-related QoL. Parents rate their child’s physical well-being of the past 7 days on a 5-point Likert scale from never (1) to all the time (5). The subscale can be transformed to a range of 0 to 100. Higher values indicate a higher physical well-being. The KINDL-R has proved to be reliable and valid [32, 33]. Cronbach’s alpha was .80 in our sample.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms in parents were measured with the 9-item depression module (PHQ-9) of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) [34]. The items have been constructed based on the diagnostic criteria for depression disorders of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) [35]. The PHQ-9 uses a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). Higher sum scores indicate higher levels of depression. The PHQ-9 is a valid and reliable questionnaire [36, 37]. Cronbach’s alpha was .85 in our sample.

Coping

We measured parental coping with the Coping Health Inventory for Parents (CHIP) [38]. The 45 items cover three main coping patterns: family (CHIP_FAM: maintaining family integration, cooperation, optimistic definition of the situation), support (CHIP_SUP: maintaining social support, self-esteem, psychological stability), and medical (CHIP_MED: understanding the medical situation through communication with other parents and consultation with the medical staff) [39]. Answers are given on a 4-point Likert scale from not helpful (0) to extremely helpful (3). Additional options are “did not use” and “could not use.” Higher scores indicate helpful strategies. The CHIP has proved to be a valid and reliable instrument [39, 40]. In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .70 for the scale CHIP_FAM, .78 for the scale CHIP_SUP, and .70 for the scale CHIP_MED.

Family functioning

We measured family functioning by using the 12-item general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD-GF) [41]. Parents rate on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4) various aspects of family functioning (e.g., problem-solving behavior). A higher total score represents lower family functioning [41]. The FAD-GF is a reliable and valid instrument [42, 43]. Cronbach’s alpha was .86 in our sample.

Statistical analyses

To determine the proportion of mothers and fathers who show a dysfunctional level of FoP, we utilized the cut-off of ≥ 34 suggested by Herschbach et al. [28]. We used Chi2 tests to investigate differences between mothers and fathers. Lastly, we conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis for mothers and fathers separately to identify factors associated with FoP. We decided for separate models to avoid a violation of the independence assumption in significance testing and to identify specific associated factors of FoP in mothers and fathers. Firstly, we included only parent-related factors (age, relationship status, education, employment status, quality of life, depression, coping pattern). Secondly, patient-related factors were added (age, gender, diagnosis, time since diagnosis, other chronic diseases or impairments, physical well-being). Lastly, we included family-related factors (family functioning, number of siblings). Dummy-coded variables were utilized when necessary. We tested the Gauss-Markov assumptions and modified the models accordingly. Additionally, we used unpaired t-tests to calculate gender differences in various psychosocial outcomes. The analyses were performed using the software IBM SPSS Statistics 27. Alpha was set at .05 for all analyses. Missing values in validated measures were imputed with the individual mean with a maximum of 30% missing data within the scale.

Results

Sample characteristics

Eight hundred ninety-nine families were potentially eligible for participation in the study. In total, 312 families participated in the survey (initial participation rate: 35%). Sixty families that were recruited via the rehabilitation clinic did not participate for the following reasons: No interest (n = 21), insufficient German language skills (n = 14), physical and/or mental burden (n = 12), cognitive limitations (n = 3), not specified (n = 10). The remaining 527 families that did not participate were recruited via the study registries. They either did not participate because they fulfilled the exclusion criteria or the health care providers in the clinics were not able to inform them about the study. From the 312 families that participated, five families were excluded from the analyses subsequently due to missing consent forms for participation (n = 2), a wrong diagnosis (n = 2), or incorrectly answered questionnaires because of limited German language skills (n = 1). In two families, only the children answered questionnaires. Hence, in this study, we analyzed the data of 516 parents of 305 families (Table 1). In 211 families, both parents participated. One hundred thirty-one of the families were recruited via the study registries and 174 in the rehabilitation clinic. There were no significant differences in FoP levels between parents in the two recruitment paths (t(511) = 0.289, p = .773).

Descriptive findings and gender differences

Fifty-four percent of the mothers (n = 161) and 41% of the fathers (n = 87) showed dysfunctional levels of FoP (Table 2). Significantly more mothers than fathers suffered from dysfunctional FoP levels (Chi2 = 8.692, p = .003). In the overall sample, the mean FoP sum score was M = 33.8 (SD = 9.4). Mothers reported significantly higher FoP and depression levels and a significantly lower QoL than fathers. We also found significant differences between mothers and fathers in coping patterns. The rating of the family functioning did not differ significantly between mothers and fathers. Looking at the parents’ rating of the patients’ physical well-being, there is no striking difference between mothers and fathers. We did not calculate gender differences for this variable to avoid a violation of the independence assumption since some parents rated the physical well-being of the same child.

Associated factors of parental FoP

The hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted using data of 295 mothers and 217 fathers of 305 families. Four mothers were excluded from the analyses since in four families two female caregivers participated. After a listwise deletion of missing data, the data of 213 mothers and 171 fathers was analyzed in the regression models. There were no significant differences in the FoP levels of mothers and fathers who were included in the regression analysis and those who were excluded due to missing values (mothers: t(293) = − 0.493, p = .622; fathers: t(212) = 0.559, p = .577). The variable relationship status was excluded for both mothers and fathers because of its low variance in our sample (96% of the fathers and 88% of the mothers in permanent relationship). The variable employment status was only excluded for fathers (93% gainfully employed). We also excluded the variable support coping (CHIP_SUP) due to a high number of missing values (Table 2). Lastly, we removed variables with an intercorrelation of r > .600 to avoid multicollinearity. Thus, QoL was excluded due to its high correlation with depression (mothers: r = − .731, p < .001; fathers: r = − .763, p < .001).

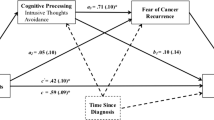

In the subsample of mothers, the parent-related factors in model 1 explained 21% of the variance in FoP (Table 3). Model 2 included parent- and patient-related factors and explained 26% of the variance in FoP. Model 3 incorporated parent-, patient-, and family-related factors and accounted for 30% of the variance in FoP. Integrating parent-related, patient-related, and family-related factors thus led to the highest predictive power. In model 3, depression, a medical coping style, and family dysfunction were associated with higher levels of FoP. Furthermore, a leukemia diagnosis of the child in comparison to a CNS tumor diagnosis was associated with lower levels of maternal FoP. In the subsample of fathers, model 1 explained 42% of the variance in FoP, model 2 explained 46% of the variance, and model 3 accounted for 48% of the variance in FoP (Table 4). In model 3, five factors were significantly associated with paternal FoP. Depression and a family coping style were associated with higher levels of paternal FoP. Additionally, a leukemia diagnosis of the child in comparison to a CNS tumor diagnosis, a higher level of education, and a higher number of siblings of the survivor were associated with lower levels of FoP in fathers.

Discussion

In this study, we determined the proportion of parents of childhood cancer survivors who show dysfunctional levels of parental FoP, analyzed gender differences, and examined associated factors of FoP in mothers and fathers.

In the overall sample, 48% of the parents reported dysfunctional levels of FoP approximately 22 months after their child’s diagnosis. Significantly more mothers than fathers suffered from dysfunctional FoP. Even though earlier studies on parental FoP that used the FoP-Q-SF/PR did not find any gender differences [19, 21], mothers reporting higher levels of psychosocial burden than fathers is a common finding in psycho-oncological research [44, 45]. Some studies on adult cancer survivors also suggest that women experience higher levels of FoP [7]. The mean FoP score of the participating parents is comparable to or lower than FoP scores in earlier studies on parents of childhood cancer patients and survivors using the same instrument [18, 19, 21]. The sample sizes in these studies were considerably smaller than in the present study. The parents in our study reported comparable or significantly higher levels of FoP than adult cancer survivors in earlier studies [24, 46, 47] and similar FoP scores to those obtained in partners of adult cancer patients [48]. Notably, the comparability of our results with earlier studies is limited due to different measurement time points.

Regarding associated factors of FoP, our results indicate that the highest predictive power was achieved by integrating parent-, patient-, and family-related factors in the regression models. Thereby, the predictive power of the model was considerably higher in fathers than in mothers. Other factors than the ones that were assessed in this study (e.g., posttraumatic stress, general anxiety) might be associated especially with maternal FoP and should be investigated in future studies. Maternal FoP was significantly associated with a higher level of depression, greater benefit from a medical coping style (e.g., reading more about the medical problem which concerns me), a child diagnosed with a CNS tumor in comparison to leukemia, and lower family functioning. Paternal FoP was significantly associated with a lower level of education, a higher level of depression, greater benefit from a family-oriented coping style (e.g., investing myself in my child(ren), trying to maintain family stability), a CNS tumor diagnosis in comparison to a leukemia diagnosis, and the child having fewer siblings. Overall, FoP was more strongly associated with psychosocial variables than with sociodemographic variables. However, previous studies on adult cancer patients also found a significant association between lower levels of education and higher levels of FoP [8]. The association between depression and FoP was also found in earlier studies on adult cancer patients [24, 25, 46]. This association might occur because of a strong tendency of people with symptoms of depression to ruminate and worry. The association between coping and FoP has been investigated with a dyadic data analysis approach in a study with 44 parental couples, which found a significantly negative association between family and support coping patterns and FoP for mothers but not for fathers [21]. In contrast, in our study the family coping pattern was associated with higher FoP levels in fathers. Further research is necessary for a better comprehension of the association between coping and FoP. A CNS tumor diagnosis in a child seems to be a risk factor for higher FoP levels in comparison to a leukemia diagnosis. This result might be related to the higher risk of progression in CNS tumor survivors [1]. Significant family-related protective factors of parental FoP are a higher family functioning for mothers and a higher number of siblings for fathers. This result is in accordance with the findings of a recent interview study with parents of childhood cancer survivors [6]. Parents reported that the family and especially the siblings are an important resource when it comes to reintegration into family life after the end of intensive cancer treatment because they claim for normality [6].

Clinical implications

Approximately one-half of the surveyed parents experienced dysfunctional levels of FoP after the end of their child’s intensive treatment. Parental FoP levels seem to be comparable to or even higher than FoP levels of adult cancer patients. Thus, psychosocial support programs targeting parental FoP are highly indicated. It should be noted that the cut-off used in this study is primarily based on statistical considerations in a sample of adult cancer patients. A recent study suggested characteristics of clinical levels of FoP [49]. A cut-off score based on clinical considerations could help health care professionals to identify parents that are in need of professional support. Initial studies on psychotherapeutic treatment approaches for FoP already exist for adult cancer patients but not for parents of childhood cancer survivors [9, 50]. In the present study, we identified associated factors of FoP in mothers and fathers. Whereas some of these factors could be targeted by health care professionals within psychosocial interventions (depression, coping, family functioning), others can provide an indication for an increased risk for higher levels of parental FoP (low level of education, CNS tumor diagnosis, fewer siblings).

Furthermore, the examination of the relationship between FoP in parents and survivors could provide further insights into FoP in families affected by childhood cancer.

Study limitations

We recruited parents via study registries and a rehabilitation clinic, because a personal contacting of the parents was not possible due to reasons of data protection regulations. A systematic non-responder analysis could not be conducted within this study design and thus, the generalizability of the results might be limited. Furthermore, an underreporting of FoP is possible since we excluded parents with particularly high levels of mental burden for ethical reasons. Additionally, it is likely that some survivors still received maintenance treatment at the time of the survey to ensure the success of the initial cancer treatment which may have affected our results. In our clinical experience, the maintenance treatment gives parents a subjective feeling of security which could lead to a lower level of FoP. Still, an opposite effect is conceivable. Lastly, due to the limited data available on FoP in parents of childhood cancer survivors, the choice of potentially associated factors of FoP was explorative and relevant factors (e.g., posttraumatic stress) might have been missed. Race and ethnicity were not measured in this study and also might constitute important risk factors of FoP. However, this study has also several strengths. We have surveyed a large nationwide sample, including both mothers and fathers, with validated questionnaires and have delivered results in a research field that is still largely unexplored. Furthermore, the STROBE Statement [51] was used for the dissemination of the results.

Conclusions

Our findings showed that a substantial proportion of parents of childhood cancer survivors report dysfunctional levels of FoP after the end of their child’s intensive treatment. Especially mothers are prone to suffer from dysfunctional FoP. As we identified depression, coping patterns, and family functioning as factors associated with FoP in mothers and fathers, these factors could be targeted in psychosocial interventions or prevention strategies. Additionally, health care professionals should pay attention to parents that may have a higher risk of suffering from FoP (low level of education, CNS tumor diagnosis of the child, survivors having fewer siblings).

References

Kaatsch P, Grabow D, Spix C. German childhood cancer registry - annual report 2018 (1980-2017). Institute of Medical Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics (IMBEI) at the University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz; 2019.

Kaatsch P. Epidemiology of childhood cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(4):277–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.003.

Ljungman L, Cernvall M, Grönqvist H, Ljótsson B, Ljungman G, von Essen L. Long-term positive and negative psychological late effects for parents of childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e103340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103340.

Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, Butow P, Lenthen K, Cohn RJ. Parental adjustment to the completion of their child’s cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(4):524–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22725.

Kazak AE, Alderfer M, Rourke MT, Simms S, Streisand R, Grossman JR. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29(3):211–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsh022.

Peikert ML, Inhestern L, Krauth KA, Escherich G, Rutkowski S, Kandels D, et al. Returning to daily life: a qualitative interview study on parents of childhood cancer survivors in Germany. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e033730. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033730.

Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z.

Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥ 5 years) cancer survivors—a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psychooncology. 2013;22(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3022.

Dinkel A, Herschbach P. Fear of progression in cancer patients and survivors. In: Goerling U, Mehnert A, editors. Psycho-Oncology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 13–33.

Zimmermann T, Alsleben M, Heinrichs N. Progredienzangst gesunder Lebenspartner von chronisch erkrankten Patienten. Psychother Psych Med. 2012;62(09/10):344–51. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1321880.

Mellon S, Kershaw TS, Northouse LL, Freeman-Gibb L. A family-based model to predict fear of recurrence for cancer survivors and their caregivers. Psychooncology. 2007;16(3):214–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1074.

Clever K, Schepper F, Küpper L, Christiansen H, Martini J. Fear of progression in parents of children with cancer: results of an online expert survey in pediatric oncology. Klin Padiatr. 2018;230(3):130–7. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0586-8921.

De Graves S, Aranda S. Living with hope and fear - the uncertainty of childhood cancer after relapse. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(4):292–301. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ncc.0000305745.41582.73.

Ljungman L, Boger M, Ander M, Ljótsson B, Cernvall M, von Essen L, et al. Impressions that last: particularly negative and positive experiences reported by parents five years after the end of a child’s successful cancer treatment or death. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157076.

Muskat B, Jones H, Lucchetta S, Shama W, Zupanec S, Greenblatt A. The experiences of parents of pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, 2 months after completion of treatment. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017;34(5):358–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454217703594.

Lindahl Norberg A, Green A. Stressors in the daily life of parents after a child’s successful cancer treatment. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25(3):113–22. https://doi.org/10.1300/J077v25n03_07.

Tutelman PR, Chambers CT, Urquhart R, Fernandez CV, Heathcote LC, Noel M, et al. When “a headache is not just a headache”: a qualitative examination of parent and child experiences of pain after childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28(9):1901–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5170.

Clever K, Schepper F, Pletschko T, Herschbach P, Christiansen H, Martini J. Psychometric properties of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire for parents of children with cancer (FoP-Q-SF/PR). J Psychosom Res. 2018;107:7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.01.008.

Schepper F, Abel K, Herschbach P, Christiansen H, Mehnert A, Martini J. Progredienzangst bei Eltern krebskranker Kinder: Adaptation eines Fragebogens und Korrelate [Fear of progression in parents of children with cancer: adaptation of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire and correlates]. Klin Padiatr. 2015;227(3):151–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1545352.

Peikert ML, Inhestern L, Krauth KA, Escherich G, Rutkowski S, Kandels D, et al. Fear of progression in parents of childhood cancer survivors: a dyadic data analysis. Psychooncology. 2020;29:1678–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5508.

Clever K, Schepper F, Maier S, Christiansen H, Martini J. Individual and dyadic coping and fear of progression in mothers and fathers of children with hematologic cancer. Fam Process. 2020;59(3):1225–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12480.

Muldbücker P, Steinmann D, Christiansen H, de Zwaan M, Zimmermann T. Are women more afraid than men? Fear of recurrence in couples with cancer – predictors and sex-role-specific differences. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39(1):89–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2020.1762823.

Tutelman PR, Heathcote LC. Fear of cancer recurrence in childhood cancer survivors: a developmental perspective from infancy to young adulthood. Psychooncology. 2020;29(11):1959–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5576.

Mehnert A, Koch U, Sundermann C, Dinkel A. Predictors of fear of recurrence in patients one year after cancer rehabilitation: a prospective study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(6):1102–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2013.765063.

Yang Y, Sun H, Liu T, Zhang J, Wang H, Liang W, et al. Factors associated with fear of progression in chinese cancer patients: sociodemographic, clinical and psychological variables. J Psychosom Res. 2018;114:18–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.003.

Peikert ML, Inhestern L, Bergelt C. The role of rehabilitation measures in reintegration of children with brain tumours or leukaemia and their families after completion of cancer treatment: a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014505. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014505.

Mehnert A, Herschbach P, Berg P, Henrich G, Koch U. Progredienzangst bei Brustkrebspatientinnen – Validierung der Kurzform des Progredienzangstfragebogens PA-F-KF [Fear of progression in breast cancer patients – validation of the short form of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF)]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2006;52(3):274–88. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2006.52.3.274.

Herschbach P, Berg P, Waadt S, Duran G, Engst-Hastreiter U, Henrich G, et al. Group psychotherapy of dysfunctional fear of progression in patients with chronic arthritis or cancer. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(1):31–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000254903.

Goldbeck L, Storck M. Das Ulmer Lebensqualitäts-Inventar für Eltern chronisch kranker Kinder (ULQIE) [ULQIE: a quality-of-life inventory for parents of chronically ill children]. Z Klin Psychol Psychother. 2002;31(1):31–9. https://doi.org/10.1026/0084-5345.31.1.31.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. Der Kindl-R Fragebogen zur Erfassung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität bei Kindern und Jugendlichen – Revidierte Form. In: Schumacher J, Klaiberg A, Brähler E, editors. Diagnostische Verfahren zu Lebensqualität und Wohlbefinden. 1st ed. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2003. p. 184–8.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M. KINDL-R. Questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. Revised version. Manual. 2000. https://www.kindl.org/english/manual/. Accessed September 2020.

Erhart M, Ellert U, Kurth B-M, Ravens-Sieberer U. Measuring adolescents’ HRQoL via self reports and parent proxy reports: an evaluation of the psychometric properties of both versions of the KINDL-R instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-77.

Ellert U, Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Kurth BM. Determinants of agreement between self-reported and parent-assessed quality of life for children in Germany – results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:102. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-102.

Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Gräfe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord. 2004;81(1):61–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003.

McCubbin HI, McCubbin MA, Cauble AE, Goldbeck L. Fragebogen zur elterlichen krankheitsbewältigung: Coping Health Inventory for Parents (CHIP) – Deutsche Version [Coping Health Inventory for Parents (CHIP) – German version]. Kindh Entwickl. 2001;10(1):28–35. https://doi.org/10.1026//0942-5403.10.1.28.

McCubbin HI, McCubbin MA, Patterson JM, Cauble AE, Wilson LR, Warwick W. CHIP — Coping Health Inventory for Parents: an assessment of parental coping patterns in the care of the chronically ill child. J Marriage Fam. 1983;45(2):359–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/351514.

McCubbin HI, McCubbin MA, Cauble E, Goldbeck L. Fragebogen zur elterlichen Krankheitsbewältigung: Coping Health Inventory for Parents (CHIP) - Deutsche Version. Kindh Entwickl. 2001;10(1):28–35. https://doi.org/10.1026//0942-5403.10.1.28.

Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9(2):171–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1983.tb01497.x.

Beierlein V, Bultmann JC, Möller B, von Klitzing K, Flechtner H-H, Resch F, et al. Measuring family functioning in families with parental cancer: reliability and validity of the German adaptation of the family assessment device (FAD). J Psychosom Res. 2017;93:110–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.11.007.

Kabacoff RI, Miller IW, Bishop DS, Epstein NB, Keitner GI. A psychometric study of the McMaster Family Assessment Device in psychiatric, medical, and nonclinical samples. J Fam Psychol. 1990;3(4):431–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.3.4.431.

Schrank B, Ebert-Vogel A, Amering M, Masel EK, Neubauer M, Watzke H, et al. Gender differences in caregiver burden and its determinants in family members of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2016;25(7):808–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4005.

Yeh C-H. Gender differences of parental distress in children with cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38(6):598–606. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.02227.x.

Koch L, Bertram H, Eberle A, Holleczek B, Schmid-Höpfner S, Waldmann A, et al. Fear of recurrence in long-term breast cancer survivors—still an issue. Results on prevalence, determinants, and the association with quality of life and depression from the Cancer Survivorship—a multi-regional population-based study. Psychooncology. 2014;23(5):547–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3452.

Hinz A, Mehnert A, Ernst J, Herschbach P, Schulte T. Fear of progression in patients 6 months after cancer rehabilitation—a validation study of the fear of progression questionnaire FoP-Q-12. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(6):1579–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2516-5.

Zimmermann T, Herschbach P, Wessarges M, Heinrichs N. Fear of progression in partners of chronically ill patients. Behav Med. 2011;37(3):95–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2011.605399.

Mutsaers B, Butow P, Dinkel A, Humphris G, Maheu C, Ozakinci G, et al. Identifying the key characteristics of clinical fear of cancer recurrence: an international Delphi study. Psychooncology. 2020;29(2):430–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5283.

Herschbach P, Book K, Dinkel A, Berg P, Waadt S, Duran G, et al. Evaluation of two group therapies to reduce fear of progression in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(4):471–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0696-1.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank all parents who participated in this study.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the “North Rhine-Westphalia Association for the Fight against Cancer, Germany” (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Krebsbekämpfung im Lande Nordrhein-Westfalen, ARGE). The ARGE was not involved in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB is the principal investigator of the study. CB, LI, and MLP developed the study concept and the design. LI and MLP developed the study materials and MLP, LI, KAK, GE, SR, DK, and LJS acquired the data. MLP analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have revised the subsequent drafts critically, approved the final manuscript to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study is part of a prospective observational study that has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Chamber of Hamburg (number: PV5277).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peikert, M.L., Inhestern, L., Krauth, K.A. et al. Fear of progression in parents of childhood cancer survivors: prevalence and associated factors. J Cancer Surviv 16, 823–833 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01076-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01076-w