Abstract

Objectives

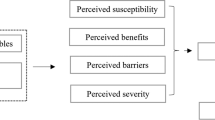

Clinical practice guidelines recommend ongoing testing (surveillance) for colorectal cancer survivors because they remain at risk for both local recurrences and second primary tumors. However, survivors often do not receive colorectal cancer surveillance. We used the Health Belief Model (HBM) to identify health beliefs that predict intentions to obtain routine colonoscopies among colorectal cancer survivors.

Methods

We completed telephone interviews with 277 colorectal cancer survivors who were diagnosed 4 years earlier, between 2003 and 2005, in North Carolina. The interview measured health beliefs, past preventive behaviors, and intentions to have a routine colonoscopy in the next 5 years.

Results

In bivariate analyses, most HBM constructs were associated with intentions. In multivariable analyses, greater perceived likelihood of colorectal cancer (OR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.16–3.44) was associated with greater intention to have a colonoscopy. Survivors who already had a colonoscopy since diagnosis also had greater intentions of having a colonoscopy in the future (OR = 9.47, 95% CI = 2.08–43.16).

Conclusions

Perceived likelihood of colorectal cancer is an important target for further study and intervention to increase colorectal cancer surveillance among survivors. Other health beliefs were unrelated to intentions, suggesting that the health beliefs of colorectal cancer survivors and asymptomatic adults may differ due to the experience of cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cancer Facts & Figures—2008. 2008, American Cancer Society (ACS): Atlanta, Georgia.

Green RJ, et al. Surveillance for second primary colorectal cancer after adjuvant chemotherapy: an analysis of Intergroup 0089. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(4):261–9.

Desch CE, et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8512–9.

Rex DK, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after cancer resection: a consensus update by the American Cancer Society and the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(6):1865–71.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(1):27–43.

Winawer S, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale—update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(2):544–60.

The NCCN Colorectal Screening Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (Version 1.2006). 2006, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

The NCCN Colorectal Screening Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (Version 1.2005). 2005, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc.

Anthony T, et al. Practice parameters for the surveillance and follow-up of patients with colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(6):807–17.

Benson AB 3rd, et al. 2000 update of American Society of Clinical Oncology colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(20):3586–8.

Simmang CL, et al. Practice parameters for detection of colorectal neoplasms. The Standards Committee, The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(9):1123–9.

Cooper GS, Payes JD. Temporal trends in colorectal procedure use after colorectal cancer resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(6):933–40.

Elston Lafata J, et al. Sociodemographic differences in the receipt of colorectal cancer surveillance care following treatment with curative intent. Med Care. 2001;39(4):361–72.

Rolnick S et al. Racial and age differences in colon examination surveillance following a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;(35):96–101.

Rulyak SJ, et al. Clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with colon surveillance among patients with a history of colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(2):239–47.

Cooper GS, et al. Geographic and patient variation among Medicare beneficiaries in the use of follow-up testing after surgery for nonmetastatic colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85(10):2124–31.

Knopf KB, et al. Bowel surveillance patterns after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer in Medicare beneficiaries. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54(5):563–71.

Ellison GL, et al. Racial differences in the receipt of bowel surveillance following potentially curative colorectal cancer surgery. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 Pt 2):1885–903.

Janz NK, Champion V, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glantz K, Rimer BK, Marcus Lewis F, editors. Health behavior and health education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 45–66.

Palmer RC, et al. Familial risk and colorectal cancer screening health beliefs and attitudes in an insured population. Prev Med. 2007;45(5):336–41.

Emmons KM, et al. Tailored computer-based cancer risk communication: correcting colorectal cancer risk perception. J Health Commun. 2004;9(2):127–41.

Macrae FA, et al. Predicting colon cancer screening behavior from health beliefs. Prev Med. 1984;13(1):115–26.

Codori AM, et al. Health beliefs and endoscopic screening for colorectal cancer: potential for cancer prevention. Prev Med. 2001;33(2 Pt 1):128–36.

Gipsh K, Sullivan JM, Dietz EO. Health belief assessment regarding screening colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2004;27(6):262–7.

Janz NK, et al. Colorectal cancer screening attitudes and behavior: a population-based study. Prev Med. 2003;37(6 Pt 1):627–34.

Rawl S, et al. Validation of scales to measure benefits and barriers of colorectal cancer screening. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2001;19(3/4):47–63.

James AS, Campbell MK, Hudson MA. Perceived barriers and benefits to colon cancer screening among African Americans in North Carolina: how does perception relate to screening behavior? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(6):529–34.

Katz ML, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas cancer education and screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007;110(7):1602–10.

Mysliwiec P, Cronin K, Schatzkin A. Chapter 5: New malignancies following cancer of the colon, rectum, and anus. In: RE C, et al., editors. New malignancies among cancer survivors: SEER cancer registries, 1973–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006. p. 111–144.

Sargent DJ, et al. Disease-free survival versus overall survival as a primary end point for adjuvant colon cancer studies: individual patient data from 20, 898 patients on 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8664–70.

Montano DE, Taplin SH. A test of an expanded theory of reasoned action to predict mammography participation. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):733–41.

Mandelblatt J, et al. Targeting breast and cervical cancer screening to elderly poor black women: who will participate? The Harlem study team. Prev Med. 1993;22(1):20–33.

Myers RE, et al. Adherence by African American men to prostate cancer education and early detection. Cancer. 1999;86(1):88–104.

Sutton S, et al. Predictors of attendance in the United Kingdom flexible sigmoidoscopy screening trial. J Med Screen. 2000;7(2):99–104.

Andrykowski MA, et al. Factors associated with return for routine annual screening in an ovarian cancer screening program. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104(3):695–701.

From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, ed. M. Hewitt, S. Greenfield, and E. Stovall. 2006: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council.

Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5112–6.

Earle CC, Neville BA. Under use of necessary care among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2004;101(8):1712–9.

Cancer Care Outcomes Research & Surveillance Consortium. 2007 April 9, 2008]; Available from: http://healthservices.cancer.gov/cancors/.

Ayanian JZ, et al. Understanding Cancer Treatment and Outcomes: The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):2992–2996.

Vernon SW, et al. Measures for ascertaining use of colorectal cancer screening in behavioral, health services, and epidemiologic research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(6):898–905.

Johnston A, et al. Validation of a comorbidity education program. J of Registry Management. 2001;28(3):125–131.

Piccirillo J. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(4):593–602.

Piccirillo J, et al. The measurement of comorbidity by cancer registries. J of Registry Management. 2003;30(4):8–14.

Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Update of ice. Stata Journal. 2005;5(4):527–536.

Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–241.

Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, 2007.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2000.

Elston Lafata J, et al. Routine surveillance care after cancer treatment with curative intent. Med Care. 2005;43(6):592–9.

Baker F, et al. Adult cancer survivors: how are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104(11 Suppl):2565–76.

Cardella J, et al. Compliance, attitudes and barriers to post-operative colorectal cancer follow-up. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(3):407–15.

Lipkus IM, Green LG, Marcus A. Manipulating perceptions of colorectal cancer threat: implications for screening intentions and behaviors. J Health Commun. 2003;8(3):213–28.

Lipkus IM, et al. Increasing colorectal cancer screening among individuals in the carpentry trade: test of risk communication interventions. Prev Med. 2005;40(5):489–501.

Edwards AG et al. Personalised risk communication for informed decision making about taking screening tests. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4): p. CD001865.

Friedman LC, Webb JA, Everett TE. Psychosocial and medical predictors of colorectal cancer screening among low-income medical outpatients. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19(3):180–6.

Christie J, et al. Predictors of endoscopy in minority women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(10):1361–8.

Levy BT, et al. Colorectal cancer testing among patients cared for by Iowa family physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(3):193–201.

Menon U, et al. Beliefs associated with fecal occult blood test and colonoscopy use at a worksite colon cancer screening program. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(8):891–8.

Sheeran P. Intention-behavior relations: a conceptual and empirical review. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M, editors. European Review of Social Psychology. John WIley and Sons; 2002. p. 1–36.

Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does Changing Behavioral Intentions Engender Behavior Change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(2):249–268.

Braithwaite RS, et al. A framework for tailoring clinical guidelines to comorbidity at the point of care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(21):2361–5.

Larkey LK, et al. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer screening among underserved Latina women: a randomized pilot study. Cancer Control. 2009;16(1):79–87.

Makoul G, et al. A multimedia patient education program on colorectal cancer screening increases knowledge and willingness to consider screening among Hispanic/Latino patients. Patient Educ Couns, 2009.

Schroy PC 3rd, et al. An effective educational strategy for improving knowledge, risk perception, and risk communication among colorectal adenoma patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(6):708–14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P30 DK034987, U01 CA093326) and by a George Bennett Dissertation fellowship from the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making and a Cancer Control Education Program fellowship from the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salz, T., Brewer, N.T., Sandler, R.S. et al. Association of health beliefs and colonoscopy use among survivors of colorectal cancer. J Cancer Surviv 3, 193–201 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-009-0095-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-009-0095-0