Abstract

Introduction

Cancer’s impact on family formation in older adulthood is not well described. Marriage rates among older adults were therefore explored.

Method

Data on the unmarried Norwegian population aged 45–80 in 1974–2001 (N = 306 000) was retrieved from the Cancer Registry, the Central Population Register, and population censuses. Marriage rates for 27600 persons diagnosed with cancer were compared to those of the general population by means of discrete-time hazard regression models.

Results

Men with cancer had a similar marriage rate as cancer-free men, whereas women experienced a 25% marriage deficit after cancer. This deficit was most pronounced after ovarian (OR 0.48) and breast (OR 0.69) cancer. Marriage rates decreased with time from diagnosis. No cancer forms elevated marriage rates.

Conclusion

Marriage rates among older male cancer survivors are similar to those of the general population. Ovarian and breast cancer in older women was associated with pronounced marriage deficits. A possible explanation is that these gender-specific cancers relate to aspects of persons’ psychological well-being, body image, and sense of femininity. Long-term adverse treatment effects are also common for the cancers in question. To explore explanations further, more details on treatment and illness progression are needed.

Implications for cancer survivors

Increased awareness of how ovarian and breast cancer may affect (prospects of) interpersonal relationships is valuable for cancer survivors and clinicians, and may facilitate communication of relevant, related issues during consultations. Our findings may suggest a need for more extensive psychosocial follow-up after these gender-specific cancer forms in older women, but further research is clearly warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Having a life partner is of great importance for persons’ life satisfaction [1]. Studies suggest that persons with poor health are less likely than others to marry and to have satisfactory and long-lasting relationships [2–5]. Cancer does not, however, necessarily have the same impact on family relations as other common illnesses. The development of a malignant disease is often hard to predict, the lethality is high in many cases, and it may not be associated with the same stigma as illnesses more obviously resulting from people’s life-style or lack of socioeconomic resources [6].

The impact of cancer on marriage rates has mainly been studied for survivors of childhood cancers, and most studies show slightly reduced marriage rates after cancer, ranging from around 5–20% for men and women [7–14]. In a recently published study, marriage rates among young Norwegian cancer survivors were shown to have become similar to those of the general population with time, although breast and female brain cancer remained associated with reduced rates [15]. Inclusion was, however, limited to persons up to the age of 45 in order to explore a possible mediating effect of fertility. Fertility will have less of an influence on marriage formation for persons 45 and older, and the effect of cancer may thus be hypothesized to be different for older and younger cancer survivors.

We hypothesize that cancer, treatment, and long-term effects will decrease marriage rates through (potential) stigma associated with the illness, smaller emotional and intimate rewards from a possible relationship, and larger practical burdens on the healthy prospective partner. Due to improvements in prognosis and an increased focus on life after cancer, marriage formation rates among older cancer survivors are expected to become more similar to those of the general population with time.

Material and method

Data from three sources were linked by means of the personal identification number assigned to everyone who has lived in Norway after 1960. The Norwegian Population Register provided information on date of birth, death or migration, dates of changes in marital status, and dates of birth of children. Educational levels were extracted from the population censuses of 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2001. Information on cancer was drawn from the Cancer Registry of Norway, which has registered all cancer cases nationwide since 1953.

A total of 305 892 never-married Norwegian men and women 45–80 years old in the period 1974–2001 were included. The 174 864 men and 131 028 women contributed each an average of 12.6 and 13.0 observation-years. The total number of marriages was 9932 among men and 4354 among women. Included in these numbers were 12 996 male cancer survivors for whom 168 marriages were registered, while 126 marriages were registered among 14 605 female cancer survivors. Only first marriages and first cancer diagnoses were considered. Discrete-time hazard regression models for marriage formation probabilities were estimated for men and women separately, using the Proc Logistic procedure in SAS® 9.1 [16]. The statistical significance level was set at 5%.

Overall effects, effects of different cancer forms, and effects of age and time from diagnosis were explored. Attained age, educational level, parity, and calendar period may influence both the chance of getting cancer and marriage rates, and were therefore included in the models and are shown in Table 1. The method and covariates are described in detail elsewhere [15]. In addition, some stratified models and models including interaction terms were set up to explore potential modifying effects of the covariates.

Results

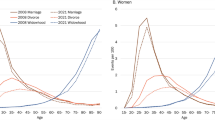

Overall effects and effects of time from diagnosis, age at diagnosis, and calendar time

Never-married men with a cancer of any form, diagnosed at any time, had a similar marriage formation rate as that of men without a cancer diagnosis, whereas cancer among women was associated with a 25% lower marriage formation rate (Table 1). Reduced marriage rates were observed with increasing time from diagnosis for both genders (Table 1). However, whereas women with recent cancer diagnoses had similar marriage probabilities as the general population, men experienced a 40% increase shortly after diagnosis.

Men diagnosed between ages 45 and 64 had an elevated marriage probability compared to the general population (odds ratio (OR) 1.37, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.12–1.67), whereas men diagnosed at earlier or later ages had similar marriage probabilities as that of the general population (OR 0.88, CI 0.67–1.15 and OR 0.94, CI 0.56–1.57, respectively). While women diagnosed at age 65 or older had a 79% lower marriage probability than cancer-free women (OR 0.21, CI 0.05–0.83), those diagnosed at earlier ages had similar marriage probabilities as the general population (OR 0.82, CI 0.63–1.06 and OR 0.81, CI 0.63–1.03).

Relative to the general population, male cancer survivors’ marriage rates did not change from 1974 to 2001 for all cancer forms combined, and only lung cancer was predicted to elevate marriage rates for cancer survivors in recent calendar time (OR 1974 0.99 vs. OR 2001 3.81, pinteraction < 0.05). Similar results were obtained on stratifying on calendar years before 1990 or 1990 and later (not shown). Among women, a strong overall increase in the marriage rate after cancer was predicted over time (OR 1974 0.51 vs. OR 2001 0.99, pinteraction < 0.05), mostly due to a strong predicted increase for breast cancer (OR 1974 0.38 vs. OR 2001 1.06, pinteraction < 0.05). Stratifying on calendar years before 1990 or 1990 and later yielded similar results, with overall OR estimates of 0.59, CI 0.43–0.80 and 0.90, CI 0.72–1.12, respectively.

No overall modifying effect was observed for parental status for men (not shown), but women with cancer with children had a similar marriage rate as cancer-free women with children (OR 1.07 CI 0.75–1.53). Childless women with cancer, however, had a reduced marriage rate compared to cancer-free, childless women (OR 0.71 CI 0.58–0.87). Among women, a high educational level was associated with lower marriage rates (OR 0.74 CI 0.60–0.91 vs. OR 0.92 CI 0.65–1.29), mostly due to a markedly reduced marriage rate among highly educated women with ovarian cancer (OR 0.43 CI 0.19–0.96). No differential effect of educational level was observed for men (not shown).

Effects of cancer site

The effects varied somewhat across cancer sites (Table 2). No cancer form was associated with a significantly elevated marriage rate, but ‘other cancers’, here defined as either unknown cancer forms or cancer forms not included in the subgroups listed in Table 2, were associated with an elevated marriage rate among men. No reductions in marriage probabilities were observed for men diagnosed with cancer. For women, statistically significant marriage deficits of 52% and 31% were observed after ovarian and breast cancer. In contrast to men, no marriages were observed for women diagnosed with brain, bone, or lung cancer.

Discussion

Male cancer survivors’ marriage rates are similar to those of cancer-free men, whereas marriage rates are markedly reduced among female survivors, mainly due to a pronounced negative effect of ovarian and breast cancer

The economic-demographic theoretical framework for this study has been presented in detail elsewhere [15]. Summarized, persons with similar intelligence, education, personality, religion, health, and other common traits are predicted to marry each other [17–19], thus encompassing cancer illness and illness consequences as a possible negative determinant in marriage formation as various physical, psychological and social effects of cancer may interfere with persons’ abilities to undertake their usual chores and obligations in relationships, either temporarily or permanently [20;21]. On the other hand, encountering and ‘conquering’ cancer has been suggested to influence life priorities and increase family orientation in both cancer patients and potential or existing partners [22], and a joint experience of cancer may enhance the quality of existing relationships [23], thus exerting a possible positive influence on marriage rates. This may be reflected here by the decreased likelihood of marriage with increasing time from diagnosis. Persons in ‘satisfactory’ relationship may be expected to marry shortly after diagnosis, while those who perceive themselves in less optimal relationships may postpone or defer marriage.

Among younger adults, both skin and testicular cancer has been found to elevate marriage rates [15], whereas no cancer types were associated with increased marriage rates in older adulthood. Brain cancer in younger women was associated with reduced marriage rates [15], but no marriages were observed among older female brain cancer survivors (OR < 0.001). Brain cancer can be extremely debilitating and alter both physical, psychological, and social functioning [24]. It may thus significantly interfere with the ability to fill the role of a life partner. Low marriage rates could thus be expected for both genders. A tendency towards reduced rates was observed also for men (OR 0.59), but the effect did not reach statistical significance. Significant marriage deficits were, however, observed after both ovarian and breast cancer. These cancers relate to aspects of persons’ psychological well-being, body image, self-esteem, and sense of femininity [25;26]. Physically, direct effects of radiation fibrosis or surgical scar tissue may cause pain with sexual activity [25]. In addition, fatigue, chronic weakness, and an altered physical appearance due to e.g. a stoma, limb amputation, or mastectomy, has been reported to negatively affect sexuality [27]. It was therefore somewhat surprising that no marriage deficits were observed after for instance cervical, uterine, or colorectal cancer. While breast cancer in general is quite visible whereas the prognosis may be unpredictable, ovarian cancer tends to be associated with extensive treatment and a great deal of suffering [28–30]. Cervical and uterine cancer, on the other hand, are less visible and has an excellent prognosis [31]. This may in part be reflected in the cancer-type variability observed in this study. To explore this further, more detailed data on illness progression, treatment regiments, and short- and long-term side-effects of treatment are needed.

Male cancer patients may experience erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction related to damage to the autonomic nervous system [32], and some men may also experience a general decrease in libido [32]. If side-effects such as these were to be of significance, reduced marriage rates could be expected after testicular, prostate, and perhaps colorectal cancer. No such effects were, however, observed. On the other hand, one could hypothesize that difficulties in areas that relate to sexuality may increase cancer survivors wish to remain in a stable relationship, and thus result in elevated marriage rates. A potential partner could, however, view actual or future problems related to sexuality or intimacy negatively, and the net effect on marriage rates is thus not easily predictable. The gender differences observed were, overall, only partly in line with our expectations.

Men diagnosed between 45 and 64 years have a higher marriage probability than cancer-free men. In this age span, fertility is a less important issue for most men, whereas it may contribute to reduce marriage rates among younger men. Men have, traditionally, been considered breadwinners, while women have been expected to perform a larger share of domestic activities, including care. This pattern may on the one hand result in men with cancer being less attractive due to their potential reduced income capacity. Our results may indicate that both educational level and income play a minor part in decisions regarding marriage formation among older men in Norway. On the other hand, some have suggested that women may be prepared to care for men, but that men may lack experience and practice in caring for women, and thus perhaps are less willing to take on responsibility for a sick partner [33]. Potential differences were, however, hypothesized to become weaker over time, as men and women perform increasingly similar roles in society [26], and also as treatment regiments have become less aggressive due to both technological innovations and increased attention towards maximizing persons’ quality of life after cancer [24].

The current study only considers marriage formation. Cohabitation has become increasingly common also among older adults in Norway, as in most other developed countries [34;35]. Also these transitions should have been modeled in order to determine whether the chance of forming any relationship, not only marriage, is affected by cancer. Unfortunately, reliable data on cohabitation are not available at present.

Conclusion

How cancer affects potential interpersonal relationships and the prospects of becoming married, is an important question for those concerned with cancer patients’ welfare, but also of interest from a more general family-behavior perspective. One could expect a stressor such as cancer to reduce the quality of both potential and existing relationships, and thus contribute to lower marriage formation rates. This was indeed observed here, but only for women and only for survivors of gender-specific cancers of the ovaries and breast. Marriage rates among older male cancer survivors were similar to those of the general population. With regards to possible mechanisms, it appears that the potentially harmful effects through lower parity, lower educational achievements, and reduced incomes are minor.

A possible explanation for the reduced marriage rates observed for the female cancers in question may relate to aspects of persons’ psychological well-being, body image, and sense of femininity. Long-term adverse treatment effects are also common for the cancers in question. To explore explanations further, more details on treatment and illness progression are needed.

Implications for cancer survivors

Increased awareness of how ovarian and breast cancer may affect (prospects of) interpersonal relationships is valuable for cancer survivors and clinicians, and may facilitate communication of relevant, related issues during consultations. Our findings may suggest a need for more extensive psychosocial follow-up after these gender-specific cancer forms in older women, but further research is clearly warranted.

References

Cairns RB, Elder GH. Costello J. Developmental Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

Lillard LA Panis CW. Marital status and mortality: the role of health. Demography 1996;33(3):313–27. doi:10.2307/2061764.

Joung IM, van de Mheen HD, Stronks K, van Poppel FW, Mackenbach JP. A longitudinal study of health selection in marital transitions. Social Science & Medicine 1998;46(3):425–35. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00186-X.

Waldron I, Hughes ME, Brooks TL. Marriage protection and marriage selection-prospective evidence for reciprocal effects of marital status and health. Social Science & Medicine 1996;43(1):113–23. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00347-9.

Blekesaune M, Øverbye E, Romøren TI. Health selection in marital transitions: Evidence from administrative data. NOVA 2003;22(03):34–52.

Goldberg RJ, Cullen LO. Factors important to psychosocial adjustment to cancer: a review of the evidence. Social Science & Medicine 1985;20(8):803–7. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(85)90334-X.

Nagarajan R, Neglia JP, Clohisy DR, Yasui Y, Greenberg M, Hudson M. Education, employment, insurance, and marital status among 694 survivors of pediatric lower extremity bone tumors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer 2003;97(10):2554–64. doi:10.1002/cncr.11363.

Byrne J, Fears TR, Steinhorn SC, Mulvihill JJ, Connelly RR, Austin DF. Marriage and divorce after childhood and adolescent cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association 1989;262(19):2693–9. doi:10.1001/jama.262.19.2693.

Langeveld NE, Ubbink MC, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA, Voute PA de Haan RJ. Educational achievement, employment and living situation in long-term young adult survivors of childhood cancer in the Netherlands. Psycho-Oncology 2003;12(3):213–25. doi:10.1002/pon.628.

Rauck AM, Green DM, Yasui Y, Mertens A, Robison LL. Marriage in the survivors of childhood cancer: a preliminary description from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Medical and Pediatric Oncology 1999;33(1):60–3. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199907)33:1<60::AID-MPO11>3.0.CO;2-H.

Ness KK, Gurney JG, Zeltzer LK, Leisenring W, Mulrooney DA, Nathan PC. The impact of limitations in physical, executive, and emotional function on health-related quality of life among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2008;89(1):128–36. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.123.

Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Jenkinson HC, Hawkins MM. Long-term population-based marriage rates among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Britain. International Journal of Cancer 2007;121(4):846–55. doi:10.1002/ijc.22742.

Mulrooney DA, Dover DC, Li S, Yasui Y, Ness KK, Mertens AC. Twenty years of follow-up among survivors of childhood and young adult acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 2008;112(9):2071–9. doi:10.1002/cncr.23405.

Punyko JA, Gurney JG, Scott BK, Hayashi RJ, Hudson MM, Liu Y. Physical impairment and social adaptation in adult survivors of childhood and adolescent rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivors Study. Psycho-Oncology 2007;16(1):26–37. doi:10.1002/pon.1072.

Syse A. Does cancer affect marriage rates? J Cancer Surviv 2008 Sep;2(3):205–14. doi:10.1007/s11764-008-0062-1.

Allison PD. Survival Analysis using SAS®: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1995.

Becker GS. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1991.

Birkelund GE, Heldal J. Who marries whom? Educational homogamy in Norway. Demographic Research 2003;8(1):1–30.

Oppenheimer VK. A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology 1988;94(3):563–91. doi:10.1086/229030.

Booth A, Johnson DR. Declining Health and Marital Quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family 1994;56(2):218–23. doi:10.2307/352716.

Schroevers MJ, Ranchor AV, Sanderman R. The role of age at the onset of cancer in relation to survivors’ long-term adjustment: a controlled comparison over an eight-year period. Psycho-Oncology 2004;13(10):740–52. doi:10.1002/pon.780.

Manne S. Cancer in the marital context: a review of the literature. Cancer Investigation 1998;16(3):188–202. doi:10.3109/07357909809050036.

Northouse LL, Templin T, Mood D, Oberst M. Couples’ adjustment to breast cancer and benign breast disease: a longitudinal analysis. Psycho-Oncology 1998;7(1):37–48. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199801/02)7:1<37::AID-PON314>3.0.CO;2-#.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2005;23(24):5814–30. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230.

Bergmark K, Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine 1999;340(18):1383–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199905063401802.

Oppenheimer VK. The continuing importance of men’s economic position in marriage formation. In: Waite L J, Bachrach C, Hindin M J, Thomsom E, Thornton A, editors. The ties that bind. Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000.

Schover LR. Sexuality and fertility after cancer. Hematology 2005; Education Program Book:523–27.

Hopkins ML, McDowell I, Le T, Fung MF. Coping with ovarian cancer: do coping styles affect outcomes. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 2005;60(5):321–5. doi:10.1097/01.ogx.0000160688.41980.59.

Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D, Onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2006;15(7):579–94. doi:10.1002/pon.991.

Fitch MI, Gray RE, DePetrillo D, Franssen E, Howell D. Canadian women’s perspectives on ovarian cancer. Cancer Prevention and Control 1999;3(1):52–60.

Carter J, Auchincloss S, Sonoda Y, Krychman M. Cervical cancer: issues of sexuality and fertility. Oncology 2003;17(9):1229–34.

Nazareth I, Lewin J, King M. Sexual dysfunction after treatment for testicular cancer: a systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2001;51(6):735–43. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00282-3.

Neff LA, Karney BR. Gender differences in social support: a question of skill or responsiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2005;88(1):79–90. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.79.

Noack T. Cohabitation in Norway: an accepted and gradually more regulated way of living. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 2001;15(1):102–17. doi:10.1093/lawfam/15.1.102.

Waite LJ, Bachrach C, Hindin MJ, Thomsom E, Thornton A. The ties that bind. Perspectives on marriage and cohabitation. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000.

Acknowledgements

Extensive thanks are due to Øystein Kravdal for the valuable help we received in data management and analyses.

Funding/Conflicts of interest:

This research was supported by a grant from the Norwegian Cancer Society. The Norwegian Data Inspectorate provided a licensure to link data. No conflicts of interests are stated.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Syse, A., Aas, G.B. Marriage after cancer in older adulthood. J Cancer Surviv 3, 66–71 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-008-0078-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-008-0078-6