Abstract

In recent years, there have been remarkable developments in the repatriation of Sámi ethnographic objects in Finland. The repatriation of large archaeological collections excavated from Sápmi, the homeland of the Sámi people (the only indigenous people in the European Union), however, has not been discussed. Based on thirteen interviews, this article examines Finnish archaeologists’ views on the repatriation of the Sámi cultural heritage. The research shows that there is suspicion or wariness towards questions of ethnicity in Finnish archaeology and a fear of political involvement, which makes the matter of repatriation an uncomfortable issue. Nonetheless, the practices of doing research in Sápmi or studying Sámi materials are changing as a result of the Sámi gradually taking a stronger role and engaging in and governing research in Finland, too, especially with the stronger role, through the Sámi parliament and the Sámi Museum, in the administration of archaeological heritage in Sápmi.

Résumé

Ces dernières années, le rapatriement des objets ethnographiques sámi en Finlande a connu des développements remarquables. Le rapatriement de vastes collections archéologiques extraites du territoire sámi, la terre natale des Sámis (le seul peuple indigène de l’Union européenne), ne fait toutefois pas l’objet de discussion. Fondé sur treize entrevues, le présent article étudie les points de vue d’archéologues finnois sur le rapatriement du patrimoine culturel sámi. Les recherches démontrent que dans le domaine de l’archéologie finnoise, les questions relatives à l’appartenance ethnique suscitent les soupçons et la méfiance, ainsi qu’une certaine crainte quant à une probable implication politique, faisant ainsi du rapatriement un sujet délicat. Les pratiques de recherche ou d’études des ressources sámi connaissent néanmoins une transformation, tandis que les Sámis jouent un rôle de plus en plus grand dans la recherche en Finlande, à la fois en y prenant part et en la gouvernant, notamment et surtout depuis que la législature et le musée sámi administrent le patrimoine culturel du territoire sámi.

Resumen

En los últimos años, ha habido desarrollos notables en la repatriación de objetos etnográficos sami en Finlandia. Sin embargo, no se ha abordado el tema de la repatriación de las grandes colecciones arqueológicas excavadas en Sápmi, la patria del pueblo sami (el único pueblo indígena en la Unión Europea). Basado en trece entrevistas, este artículo examina los puntos de vista de los arqueólogos finlandeses sobre la repatriación del patrimonio cultural sami. La investigación muestra que existe sospecha o cautela hacia cuestiones de etnicidad en la arqueología finlandesa y un temor a la participación política, lo que hace que la cuestión de la repatriación sea un tema incómodo. No obstante, las prácticas de investigar en Sápmi o estudiar materiales sami están cambiando como resultado de que los samis asumen gradualmente un papel más fuerte y participan y guían las investigaciones en Finlandia, especialmente con su papel más fuerte en la administración de patrimonio arqueológico en Sápmi a través del parlamento sami y el Museo Sami.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In February 2017, the Sámi people of the Nordic countries celebrated the 100-year anniversary of the first Nordic meeting of the Sámi representatives in Tråante or Trondheim. For a week, the Norwegian city bustled with Sámi from Finland, Norway, Sweden and Russia. Sámi events, seminars, exhibitions and concerts were held and meetings of, for example, the Sámi parliaments of Finland, Norway and Sweden were organized. One attraction during the festivities was the exhibition called Bååstede (a South Sámi word for “return”) that showcased a number of objects belonging to a large collection of ethnographic Sámi objects to be repatriated to Sámi museums in Norway.Footnote 1

Elina Anttila, the Director General of the National Museum of Finland, and Juhani Kostet, the Director of the Finnish Heritage Agency, were among the invited guests at the opening of the exhibition.Footnote 2 For Anttila—she later reflected—the Bååstede exhibition was the final stimulus towards the process that resulted in the repatriation of the largest and oldest Sámi ethnographic collection in Finland to the Sámi Museum Siida in April 2017. Over 2600, Sámi objects will return to Sápmi.Footnote 3

Although especially important and extensive, the National Museum collection was not the first Finnish museum collection to be repatriated to the Sámi Museum Siida. In April 2015, the Tampere Museum Center Vapriikki returned a collection of some 40 Sámi objects that had been collected in the beginning of 20th century. In October 2016, the Museum of Hämeenlinna followed the lead by repatriating 23 objects, the oldest from the beginning of the 19th century. The most recent Sámi repatriation in Finland took place in April 2018 when Lusto, the Finnish Forest Museum, returned some 20 Sámi objects from the early 20th century. The returned collections supplemented the Siida collection with older artefacts than it had previously possessed, in addition to which the repatriations increase equality between Sámi and Finnish museums.

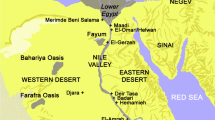

The repatriation of ethnographic objects has been discussed in Finland since the 1990s, albeit in a rather circumspect manner (Harlin 2008a, b; Harlin and Olli 2014; Lehtola 2005), whereas the repatriation of the large archaeological collections excavated in Sápmi has not really been publicly discussed. The archaeological collections are under the control of the Finnish Heritage Agency (formerly the National Board of Antiquities) and physically located in the capital city of Helsinki, in southernmost Finland, some 800 km away from the southern border of Sápmi.

This article examines issues related to the repatriation of archaeological collections derived from Sápmi in Finland. More specifically, I focus on how Finnish archaeologists, who have conducted research in or on Sápmi, perceive questions of repatriation. The article is structured around three themes. First, I seek to provide a general picture of how the interviewed archaeologists conceive and relate to the idea of repatriating archaeological collections from the Sápmi back to the Sámi. Second, I consider how ethnicity and its identification from archaeological material feature in their views of repatriation; this question was repeatedly brought up in the interviews and is therefore a central topic of this article as well. Third, the relationship between archaeology and politics emerged as a central topic in the interviews and comprises the last theme of the article.

The empirical material for the article is derived from interviews with thirteen Finnish archaeologists, conducted in 2014–2015, and focusing on questions of repatriation, governance of archaeological materials and the cultural self-determination of the Sámi in Finland. The interviewees were of both sexes and of different ages. They have studied archaeology as their main subject at the University of Helsinki, University of Oulu or University of Turku. All are ethnically Finns and speak Finnish as their mother tongue, hence belonging to the majority population in the country. At the time the interviews were carried out, there were no formally trained archaeologists with an ethnic Sámi background in Finland; the first Sami person with a degree in archaeology graduated from the University of Helsinki in 2016. In total, there are an estimated 250 trained archaeologists in Finland, though less than a hundred are actively practising archaeology, and only a handful have engaged with the archaeology of Sápmi or Sámi issues. There were some twenty archaeologists in Finland who were actively studying, or had studied, questions directly related to Sápmi or Sámi issues. They have been employed as researchers at universities, the Finnish Heritage Agency, provincial museums, or Metsähallitus, the state enterprise governing state-owned land. The interviews were semi-structured and conducted in Finnish, with a questionnaire sent to the interviewees beforehand. The interviews were carried out at their home, workplaces or in restaurants and cafes, and they generally took the form of an informal conversation rather than formal interviews.Footnote 4

Finnish Archaeology, Sámi Repatriation

In brief, repatriation means returning cultural heritage and knowledge, collected by museums or other institutions, to the source communities. Repatriation practices include committing source communities to research or transferring the control of heritage to them. In some cases, the museums of the majority population can continue preserving and exhibiting artefacts, following the norms of the source community. Repatriation has been discussed especially in the context of indigenous archaeology which seeks to integrate indigenous worldviews, values, interests and experiences in research (see, e.g. Atalay 2006; Nicholas 2008, 2010, 2014; Porsanger 2018; Smith and Wobst 2005; Watkins 2005). Indigenous archaeology appreciates the indigenous right to self-determination like repatriation, the right to reburial, the use of traditional knowledge and history. The Sámi have been highly active in the global networks of indigenous peoples from early on (Niezen 2003; Valkonen 2009), but indigenous archaeology is yet to become mainstream in Nordic archaeology, and the concept has been the subject of explicit discussion only recently (see, e.g. Ucko 2001; Spangen et al. 2015; but cf. Olsen 2016). However, indigenous archaeology has been criticized for re-enabling the domination of the western scientific community in the field (e.g. Gonzales-Ruibal 2010; Tuhiwai-Smith 2008). It is nonetheless curious that an existing tool has not been more actively adopted in the political discourses of self-determination within the Sámi community, as it would be one way of integrating Sámi voices in the discourse of Nordic archaeology.Footnote 5 In the recent Advances in Sámi Archaeology conference, the Sámi researcher Jelena Porsanger indeed urged archaeologists working in Sápmi to engage with indigenous archaeology as a theoretical framework (Porsanger 2018).

In Norway, Sámi prehistory and history have comprised a specific field of research since the 1980s, as reflected in the common use of terms such as Sámi archaeology or Sámi prehistory (Bergstøl 2009; Hansen and Olsen 2014, pp. 2 and 5–6; Hesjedal 2000. p. 167, 195; Mulk 1994, pp. 4–5; Odner 1984; Olsen 1986; Schanche 1994, Schanche 2000, p. 93; Schanche and Olsen 1985; Simonsen 1982, p. 67, Storli 1986). Similar developments have not occurred in Finland or Sweden where such concepts have been considered irrelevant or too loaded, and there is no generally agreed-on Nordic definition of what constitutes “Sámi archaeology” (Ojala 2009, p. 61; Carpelan 2003, p. 60; Hamari 1998, pp. 68–69; Rankama 1996, pp. 490–497). Indeed, Sámi pasts have traditionally been studied within the modern borders of Finland, Sweden and Norway, and only occasionally across borders (Storli 1993a, b; Mulk 1993; Carpelan 1993; Hesjedal 2000, pp. 209–211; Schanche 1994, pp. 30–31; Zachrisson 1997).

One possible reason for the Nordic reluctance to engage with questions of repatriation is that they are intertwined with the troubling issue of Nordic colonialism and its legacies, which—as several researchers have argued (Gabriel 2010, p. 9; Naum and Nordin 2013, pp. 3–4; Lehtola 2015a)—has not been taken seriously enough in the Nordic countries. Instead, Nordic colonialist policies and practices directed to Sápmi have been ignored or downplayed. In Finland, for instance, colonialism has been rendered unimportant or even non-existent (Kuokkanen 2007, pp.146–147; Yle 2012; Levä 2013; see further Lehtola 2015a). Colonialism has been understood in very narrow terms, and the idea of scientific colonialism (Nicholas and Hollowell 2010; Ojala and Nordin 2015, p. 16), for example, has traditionally attracted little attention in the Nordic countries. According to the Sámi researcher Rauna Kuokkanen, however, colonialism should not be seen as a historical event, but an ongoing process that subordinates indigenous peoples (Kuokkanen 2007, p. 146).

The definition of Sáminess has been subject to debate and controversy in Finnish archaeology in the 2000s. This has been due to Sámi activism and has become more conspicuous than before. This is probably the result of the affiliation with the global community of indigenous peoples, which has been seen to result in the politicizing of questions regarding the Sámi ethnic past. Many (ethnic) Finns also fail to value what they regard as (real or imagined) “special rights” that minorities and indigenous peoples (are thought to) have towards protecting their culture. This subject comes up in debates over Sáminess (e.g. Pääkkönen 2008, pp. 13–14; Lehtola and Länsman 2012, p. 13; Lehtola 2015b, pp. 183–184).

Along with many others, Sari Valkonen, the Director of the Siida Museum, has greeted the repatriation of the ethnographic collections as a positive move supporting the law of cultural self-determination (regarding the Sámi language and culture) that was enforced in 1996 in the Finnish Sámi territory. It is monitored and enforced by the Finnish Sámi Parliament, the highest political organ of the Sámi people. Due to the limitations of the legal jurisdiction of the Sámi Parliament (e.g. Valkonen 2009, p. 151), however, cultural heritage and cultural environments still continue to be administered by the state of Finland through the National Museum of Finland and the Finnish Heritage AgencyFootnote 6 (Antiquities Act 1963).

A permanent Sámi Cultural Environment Unit has operated in the Sámi Museum Siida since 2015. The unit—for the first time located within the Sámi territory—is responsible for some aspects of heritage governance, but for instance, permissions for archaeological fieldwork in Sápmi are still granted by the Finnish Heritage Agency (e.g. Magga and Ojanlatva 2013; Guttorm 2014). Consequently, Sámi institutions, such as the Sámi museum, are not necessarily even aware of archaeological research in the Sámi area. As Tiina Sanila-Aikio, the President of the Finnish Sámi Parliament, indicated in her speech in the 2018 Advances in Sámi Archaeology conference, and archaeological material should be studied from a Sámi perspective which includes acknowledging the values and needs of the Sámi people (Sanila-Aikio 2018).

Archaeological fieldwork in Finland is nowadays often driven by redevelopment and takes the form of rescue excavations under the direction of the Finnish Heritage Agency or a private company. This kind of “administrative archaeology” is generally not concerned with social aspects of the research, such as engaging with local communities or even informing them about the projects. The Sámi Cultural Environment Unit had not yet been officially formed at the time of my interviews, which nonetheless often touched upon or reflected on the role of Sámi institutions in the administration of archaeological collections from Sápmi.

“Finns Don’t See the Sámi as Different from Themselves”

The interviews indicate that repatriation is seen more relevant elsewhere than in Finland. As one interviewee put it, “It’s a very distant matter—that concerns South-America, possibly the reliefs of Parthenon” (A 13). While many interviewees supported the repatriation of cultural heritage in principle and regarded it as an important matter, it was often seen to be about returning artefacts to their source areas in general, and not specifically an indigenous issue. “It could just as well be a SavonianFootnote 7 issue, I don’t know if it’s more significant for the Sámi” (A 13).

Several interviewees pointed out that there is little “discussion” in Finnish archaeology in general, which was seen to explain, at least partly, why repatriation has gained little attention. Ethical issues, for instance, have gained serious attention only very recently. Thus, repatriation was considered an example of broader problems, rather than an issue of importance in its own right. One interviewee reflected that although there have been demonstrations abroad in support of repatriations, in Finland “only few archaeologists have reflected on the matter, so it isn’t really an issue. It is perhaps familiar to those who have worked with northern issues, but unfamiliar to archaeologists working in the south” (A 8). Another interviewee commented:

Many archaeologists don’t care a bit. I think this is the problem. Some people may talk about it amongst themselves - - - I don’t think that southern archaeologists deliberately mean to neglect Lapland.Footnote 8 I don’t believe it is about colonialism, it just doesn’t… There are only a few of us [archaeologists in Finland] and we have always studied what has been necessary. (A 11)

The interviews suggest that repatriation is not a question of a particular importance in Finnish archaeology and that the few archaeologists informed on the matter cannot be expected to keep up the discussion on the topic. The association between “southern archaeologists” and colonialism in the above quote is interesting, as it suggests an awareness between the two. Another interviewee refers to the common perception that “the Sámi in Finland haven’t suffered similar injustice as [indigenous peoples] in other countries” (A 4). Consequently,

[Finnish] people don’t feel enough guilt in this respect. If you think about the history of Sweden and Norway, it is on an entirely different level. Finns don’t see the Sámi as different from themselves similarly as Scandinavians do. We feel they are quite similar in many respects. We don’t see any opposition [between Finns and Sámi], nor do we consider that Sámi collections could be differently treated from Finnish collections (A 4).

The Sámi are considered to have a good position in Finland where the state is not considered to have inflicted injustice and assimilation policies comparable to Norway and Sweden,Footnote 9 which in turn has curbed academic and/or social discussion on repatriation. According to the comment, the Sámi have a good position in Finland, and therefore, they should just accept the prevailing situation. Moreover, Finns and Sámi people are likened to each other.

The myth of equality is strong in Finland and has long obscured the colonial history of the country (see Lehtola 2015a), and Sáminess indeed tends to be considered a peripheral extension of Finnishness (Karjalainen 2015, pp. 154–166; Lehtola 2015a, pp. 27–28, 2015b, pp. 56 and 221; Guttorm 2013). Consequently, the Sámi constantly need to demonstrate the difference of their culture and ways of life to those of the Finns (Lehtola 2015b, p. 240).

The supposed similarity or at least closeness of the Sámi and Finns is seen as a reason why repatriation of archaeological collections has not really been discussed in Finland. “The question of repatriation has not come up in connection with Sámi artefacts, so there is no problem there” (A 13). On the other hand, a need for developing repatriation policies was also identified:

From my point of view, it seems clear that these debates take place everywhere in the world and should also take place here. Why is there no discussion about it? Do we even try to start it? What is the situation in other universities and departments where civil servants have been, and are being, educated? Are these matters talked about, do people understand how important this issue is globally? Perhaps discussion on the issue is not objected to, people just don’t realize its importance. (A 2)

This reflection corresponds to the recent finding (Harlin 2015) that the archaeology programs at Finnish universities fail to provide sufficient education on indigenous issues, including repatriation, despite their relevance and internationally recognized significance. In Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, for example, repatriation is an essential part of museum work (Tythacott and Arvanitis 2014, p. 9).

Overall, the interviews indicate that repatriation is, or at least still was some years ago, a rather poorly known concept and phenomenon in Finnish archaeology, and nor is it considered particularly relevant in the context of Finnish archaeology conducted in Sápmi. The interviewees usually considered repatriation on a general level although a feeling was frequently expressed that the Finnish archaeologists with distinctively “northern interests” are, or should be, more informed than others about this issue. This suggests that repatriation is regarded as particularly closely connected to the Sámi despite the common posing of the problem of whether the questions related to the Sámi/Sápmi are any different from other parts of Finland. It is noticeable, too, that a passive voice was often employed when talking about repatriation, which serves as a means of distancing oneself from a difficult topic.

Overall, the interviews suggest that the failure in Finnish archaeology to engage with indigenous issues in general, and repatriation in particular, is due to circumstantial reasons (e.g. socio-historical or related to research traditions) beyond the command of archaeologists themselves, thus implying dissociation from the topic. Colonialism did not feature as a significant theme in the interviews, probably partly because it was apparently understood in a narrow sense—that is, an officially sanctioned or actively expressed suppression of indigenous people readily or directly identifiable from historical sources, rather than a diverse set of colonial ideas and practices “invisibly” embedded in the social structure, as for instance in the case of scientific colonialism (see, e.g. Lehtola 2015a).

The discussions with the interviewees also demonstrated, however, that Finnish archaeologists have a deep personal interest in Sámi archaeology and Sápmi as an environment, and it is just that the Finnish ideology of equality obscures the fact that the Sámi do actually comprise an indigenous nation separate from ethnic Finns (and Scandinavians). This in turn has implications for cultural self-determination, part of which covers repatriation policies and the implications are that the Sámi are an (officially defined) indigenous people, with certain rights (Guttorm 2013; Karjalainen 2015, pp. 154–166; Lehtola 2015a, pp. 27–28; 2015b, pp. 56 and 221). The Sámi, in other words, is not merely yet another “Finnish tribe” like, say, the Savonians or Tavastians, or Sápmi another province of Finland although this kind of idea was frequently rehearsed in the interviews.

The Problematic Origins of the Sámi

One of the main issues that emerged during the interviews was “where to draw the line with Sáminess” (A 9), which in turn is linked to the question of the origins of the Sámi identity, or when it is possible to speak of an (archaeologically) identifiable Sámi ethnicity. This question took a prominent role in my interviews, as it was evidently regarded as a definitive question of what qualifies as “returnable” archaeological material.Footnote 10

The interviewees approached this question from different angles. One suggested that it would make sense to talk about the (present-day) Sámi territories, rather than Sáminess as such, because then “we are not obliged to find a distinction of what is Sámi and what is not”, without having “to determine when the Sámi can be recognized as an ethnic group from archaeological material” (A 10). On the other hand, this approach was not considered unproblematic either, as the Sámi territory has presumably been more extensive in the past and therefore “a lot of Sámi artefacts would still remain in the hands of Finns” (A 5). One interviewee expressed support for the repatriation of younger material, but had reservations about the older material.

I don’t see any sense in repatriating Stone Age artefacts, it would be merely a political decision to return them. I don’t believe that the locals are interested in them – well, perhaps apart from axes. It doesn’t serve a purpose, let’s put it that way. To what degree do the locals identify themselves with Stone-Age materials […] It seems a bit trivial to me. (A 11)

Archaeologically, it may seem far-fetched to trace the origins of present-day ethnic groups back to the Stone Age. But for the indigenous peoples roots can be “timeless”, as Jelena Porsanger (2018) pointed out in her discussion about indigenous understanding of the “ancestors” (dološ olbmot). The Sámi cosmology, with its cyclical concept of time, renders the past—including archaeological sites—a relevant part of the past regardless of their specific dating. In this view, repatriating “too old” objects is not a question of proving a lineage connection scientifically, but nonetheless seen as products of the ancestors and therefore meaningful to the Sámi community. This also raises the question of whether there is any accessible material that locals could consult towards a better understanding of scientific perspectives on the significance of the archaeological material on the one hand and the significance of repatriation on the other. Porsanger emphasized the importance of repatriating information and using it to empower local values and aspirations (Porsanger 2018). The general spirit of the interviews, however, was that keeping archaeological collections in Helsinki is a “correct” and “natural” state of matters and that the material from Sápmi should be regarded differently in this respect.

The question of the origins was employed, in some of the interviews, to highlight the uncertainty of studying the past, and particularly, how the “common people” understand the nature of archaeological knowledge. Understandable as this may be in a “scientific” view, it also seemed to be used a shield against engaging with the contemporary issues of repatriation. The uncertain character of archaeological knowledge was sometimes emphasized to a notable degree: “some kind of answers surely must be found from the archaeological material, that’s what we are for, but nobody should think that they are correct” (A 8). Several interviewees also emphasized the need to distinguish between scientific views and “attitudes”:

I have understood that at least some [archaeologists] think that the question of the origins is fairly unnecessary. The Sámi and others just are there and then at some point back this question becomes irrelevant in their opinion, or it becomes speculative, or difficult in some other way, difficult to argue for [this way or that]. It is not necessarily a question of attitude, that there was a negative or other kind of attitude towards the Sámi, but it’s this kind of a scientific vantage point. (A 13)

This view reflects an awareness that questions of ethnic identities and their origins are not irrelevant to the Sámi, while cautioning on the ability of archaeology to provide answers to them. Another interviewee similarly reflects that it is “an anthropological, humanistic question, it isn’t within the basic competence of Finnish archaeology” (A 11). The Finnish training in archaeology is seen to discourage engagements with matters of ethnicity: “We archaeologists, it has been said, must not take a position in questions of ethnicity.” (A 5) Overall, the lack of competence and the difficulty of determining the “roots” of ethnic groups in scientific terms were considered as preventing the development of an informed view of what constitutes Sáminess in prehistory, hence also making it impossible to define what archaeological finds and collections should be within the scope of repatriation policies in principle. Indeed, one interviewee observed that some archaeologists find the question of origins so difficult that they do not even want to discuss it; this has nothing to do with attitudes to the Sámi, but simply arises from the limitations of science. It is noticeable that “science” frequently featured in the interviews as a highly abstract and somewhat idealized frame of thinking and practice, which render archaeologists as by-standers in the face of contemporary societal discussion related to Sámi issues. They are the “facts” and the “prevailing state of things”—basically forces beyond archaeologists and archaeology—that are seen to strip archaeologists from agency and make them outsiders in the sensitive matter of the indigenous rights.

There can be little doubt that recognizing ethnic groups from archaeological material is difficult, and this topic has been subject to discussion and debate in Nordic archaeology since the 1980s. “Descent is a complex matter when you go back in time” (A 13), one of the interviewed archaeologists said while another reflected:

I think that people may start studying it, but when you look deeper, you realize that there are big problems there. It is difficult to know how things are inherited and many cultural phenomena should point in the same direction [to enable identifying past ethnic identities]. Ethnicity has been studied, but it has always been discovered that it is problematic (A 6).

Cultural traits and influences are recognized to mix over centuries and millennia: “We know from history that the Sámi have absorbed traits from other ethnic groups. People have not been isolated. It is difficult to say which phenomena have been exclusive only to certain groups” (A 4). Likewise, “Artefacts don’t determine anyone’s ethnicity. Both Sámi and Finns have immensely long roots. Ultimately everybody is related to everybody else” (A 12).

That Finnish and Sámi people are “relatives” is often emphasized and it is, in some ways, entirely true that “ultimately everybody is related to everybody else”. At the same time, however, such a position is quite problematic because the “shared history” tends to become a Finnish history in Finnish terms with the Sámi and Sáminess in the margins. It is illustrative of this asymmetry that the most recent general overview of the prehistory of Finland, Muinaisuutemme jäljet (The Traces of Our Past) (Haggrén et al. 2015), contains 619 pages, with the Sámi mentioned only on 12 pages and a mere 1,5 pages specifically dedicated to them.

Only one interviewee observed that studying the origins of the Sámi from archaeological material and from a theoretically informed manner could actually be useful for developing a more general theory of ethnicity, hence also making the archaeology of Finland more interesting on the international arena (A 2). The interviewee contemplates that ethnicity

is a difficult subject, but more attempts have been made to study it in some times than in others. it has been studied more and has been studied more in certain times than others […] The last time it was studied [enthusiastically], there was optimism in the air, there were [new] genetic methods, etc., but then it couldn’t be cracked it anyway. There was thrill and disappointment. (A 2)

The interviewee refers to the late 1990s and early 2000s, when there was an open and multidisciplinary discussion about ethnicity in prehistory in Finland, and “it wasn’t considered problematic” (A 10). But when the results from different disciplines appeared to point in different directions, and they could not be harmonized, the discussion dried up.

Traditionally, the origins of the Sámi have been studied in Finland primarily from a linguistic perspective (Tallgren 1931, p. 209; Carpelan 1975, pp. 38–41; 2002, p. 189; 2008, p. 321). Many archaeologists feel that they lack the competence to study the origins of ethnic groups because it is seen to require specialized skills that few have, in particular tackling a multidisciplinary approach that draws from archaeology, linguistics and genetics (see, e.g. Carpelan 2000, p. 189, Halinen 2011, p. 135). Moreover, combining the results from different fields can be problematic (e.g. Saarikivi and Lavento 2012). The real and perceived difficulty of the research also makes it easy to simply avoid it. As one interviewee reflected, “Now that linguists have argued for the young age of the Sámi language in that region… no one wants to step into an area you know nothing about, and then linguists may come and tell you that you cannot say this”Footnote 11 (A 10). Thus, it feels almost intimidating to speculate on the origins of the Sámi when criticism from other disciplines can result in embarrassment.

“Nowadays—Everyone is Scared of Sáminess”

It has been argued for a long time that archaeological questions about the Sámi, including their origins, should be studied in a pan-Fennoscandian perspective, across national borders rather than within the borders (e.g. Aspelin 1885, p. 30; Tallgren 1931, p. 209; Äyräpää 1937 b, pp. 68 and 71; 1953, p. 98; Carpelan 1966, pp. 74–75; Olsen 1994, p. 121; Halinen 1999, p. 126; Schanche 2000, p. 346; Hansen and Olsen 2014). As one interviewee observed, however, the scope of this subject is “really broad, I would have to study the material on the Norwegian and Swedish side, it’s that kind of a question. I avoided it, I didn’t have the guts” (A 7).

One interviewee sees the matter effectively impenetrable, an “extremely difficult question, the answer to which depends on one’s vantage point, how one views the relevant material and the question. I have a feeling that there is no final answer” (A 4). The question of the origins, then, is apparently not neutral, and the answer depends on the personal views of the researcher. This seems to echo the long-standing dispute over the definition of the Sámi in Finland,Footnote 12 which is associated with the right to vote in the Sámi Parliament (Lehtola 2015b). Another interviewee reflects that

Nowadays, not only in archaeology but also more generally, everybody is afraid of the issue of Sáminess. If you get involved. It is better to just be quiet and get around it. When you sink deep into such complex questions. The difficulty of things makes people avoid the topic, knowing that things should be repatriated, but how to position oneself in relation to this difficult topic. (A 9)

Talking about Sáminess seems to be associated with taking a stance in a political dispute.

It is such a controversial issue, you’d be forced to pick a side, to be with one party and against another. This is especially true with this Sámi question, and I don’t want take a stand, to be considered as belonging to anyone’s “gang”. As a researcher, I want to have as much freedom as possible. I don’t want be questioned for belonging to one group instead of another (A 11).

The proposed association of Sáminess and “freedom of research” is interesting in proposing that one might exclude the other. Or as another interviewee put it:

Can archaeology provide answers? Not necessarily. It is surely problematic from the viewpoint of research if you take a stand and your view doesn’t please everyone – you end up in a situation where you become branded for life and can no longer practice scientific research. The local welcome can be unpleasant. You lose your reputation, and your reputation as a researcher as well. (A 10)

In general, the interview data reflect a desire to stay away from disputes and different interest groups or “gangs”, as they tend to be referred to, and thus, disengage from discussions that are perceived to require “taking a stance”. Many of the interviewees seemed to feel that studying the origins of the Sámi is more of a political than an archaeological question. Therefore, many were shy to engage with the discussion due to the fear (real or perceived) of being stigmatized and even becoming persona non grata in the rather small circles of Lapland.

One of the interviewees specifically emphasized the neutrality of archaeological research: “In land right issues, the opposing sides are the Sámi and the others. Archaeologists just want to document” (A 9). There seems to be the feeling, though, that this might be an impossible task:

The current situation somewhat restricts what matters you can go into and what kind of assumptions or hypotheses you present to the debate. I mean that Sámi debate that has been going on for many decades. (A 7)

The dispute over the definition of the Sámi has arguably contributed to the unwillingness to discuss ethnicity in Finnish archaeology: “In our times, or now recently, archaeology has become more political than before, it is employed on both sides [of the debate]. That is, how has the North been conceived, or what stage in the past does it make sense to talk about the Sámi and stuff” (A 5). Another interviewee proposes that the situation has become more political than before, with different groups watching for their interests: “Many values and goals are involved. The interests of different ethnic groups, even political interests make the issue difficult to some extent” (A 3).

Many interviewees expressed the fear that if archaeological material was under the governance of the Sámi parliament, they would no longer have access to it, which could lead to “unmerited advantage or descent determining whether someone is allowed to do one’s work. Every archaeologist must have the right to do their work without restriction; it’s a discriminating starting point, even the thought of it” (A 12). The Sámi administration seems to be associated with discrimination in the minds of Finnish archaeologists.

If they [the finds and administration] are governed by the Sámi Parliament, is it then the decision of the parliament that Sámi materials can only be studied by ethnic Sámi? Classically, the scholars studying Lapland are from Helsinki or Southern Finland. I think it has been nice that it hasn’t been focused on one’s own roots but driven by scientific interests. It has not been “Heimat” archaeology. (A 9)

According to the interviews, “Heimat” archaeology seems to feature as an opposite to “scientific” research. It seems to be deemed an ideal that researchers have no personal connection with the area and material they are studying, that an “emic” viewpoint could be harmful. The interviews also reflect a deep distrust in the workings of the Sámi Parliament.

If we think about the Sámi territory, which is politically highly charged in many ways, and they are fighting with each other, and have been fighting throughout history about who is better and who is worse, so that these kinds of political pressures can influence a person working in Siida, although the museum has the best archaeological expertise in the region, and is actually based there, it has many negative aspects to it. (A 11)

The mode of talking about the Sámi is often patronizing, with an implication that the Sámi are incompetent to control their own lands, because there are disagreements over how it should be done. The idea of the “quarreling Sámi” is commonly replicated in the public discussion—unlike Finns (the discourse suggests), the “quarrelling Sámi” cannot be impartial (e.g. Valkonen 2009, pp. 200–201; Lehtola 2015b, p.19, 81, 183 and 258). The archaeologists interviewed express the worry that archaeology is brought onto a battlefield of a (non-archaeological) kind: “Who is being pleased?” (A 1). Another archaeologist similarly reflected that these questions “please some people and not others” (A 4), with the implication that discussing repatriation is about pleasing one interest group and turning one’s back on another. The image of the Sámi being incapable of “deciding amongst themselves”, means it seems easy to just keep the archaeological material in under the control of the Helsinki-based administration.

Apolitical Archaeology?

Archaeology has a colonial history and is founded on western values and ways of thinking (e.g. Atalay 2006, p. 280). Like the study of folklore and folk poetry, Finnish archaeological research was born in the late 19th and early 20th century to provide the Finnish people with a national identity and history Nuñez (2011), p. 99; Fewster 2006). Myths, historical narratives and folklore were used to paint an idealistic picture of national unity building towards a nation state (see, e.g. Carr 1986; Hodder 1991). The study of ethnicity tends to be considered as nationalistic, even racist, and the subject has been avoided in Finnish archaeology due to the fear that archaeology would become politicized, with the dark heritage of the Second World War looming in the background (Nuñez 2011, p. 93)

The nationalistic background of Finnish archaeology has faded away, indeed to the degree that associating archaeology with “national questions” feels uncomfortable and even reprehensible. The political nature of archaeology and heritage has been increasingly identified and discussed since the 1980s and is now widely recognized as an important theme (see, e.g. Jackson and Smith 2005, p. 309; Hamilakis 2007; Jones 1997; Nicholas 2010, p. 239; Nuñez 2011, p. 93; Mc Guire McGuire 2008; Meskell 1998, 2018; Ojala 2009; Smith 2004; Smith and Wobst 2005; Wood 2002). As an interviewee put it, “Research history restricts, we have seen how archaeological interpretations have been used politically in ways that archaeologists didn’t want them to be used. The burden of research history has its influence [on contemporary archaeological research]” (A 7). Indeed, this view was frequently repeated in the interviews:

I’ve personally tried – because it is a very political issue – I’ve tried to avoid becoming involved in these political disputes. I’ve always stood for pure science, I wouldn’t like to mix it, science being deliberately used as a political tool, I just don’t like it, personally (A 11).

Many interviewees emphasized that they feel uncomfortable with the idea of their work being considered political. “Politics doesn’t belong with archaeology; the archaeologist focuses on how cultural heritage is best preserved” (A 6). The nationalistic research tradition was commonly mentioned and seen as something that one would better keep clear of, especially with regard to the Sámi.

[Archaeology] has sometimes been done for specifically political purposes, but I think a political starting point should be avoided, it shouldn’t be there. My take is that I try to discover new information, so it’s not politics. I admit that an outsider might well think that I, as a Finn, go up there and acquire research material which I can then process so that somebody can use it to support whatever political goal, and of course this can also happen. (A 13)

Archaeology in itself is seen as inherently apolitical, even if non-archaeologists may end up “manipulating” it for political purposes, with the shadow of various nationalistic ideologies, in particular, looming in the background. The problem is, however, that such “misuse” of archaeology can also happen today, especially if archaeologists themselves refrain from societal discussion. Although the following interviewee wants to keep away from political discussions, he/she ends up taking a stand on the ethnic situation in the Sámi territory:

Situations change; people move, ethnic groups merge with each other and separate. Sáminess is not stable. The well-being of indigenous peoples is a fine thing, but special land rights, especially as argued from the grounds of archaeological knowledge, should not be granted in the areas of the present Sámi territory, for example. There are Finnish families that have lived there for centuries, they cannot be ignored just because the Sámi have inhabited the area for an even longer time. (A 3)

The interviewees generally wanted to withdraw from the discussion of ethnicity, often by referring to the shared roots of northern cultures and “equality” between them:

Should prehistoric finds be used as an extension to something, in other words something close to politics? I see this not only as a Sámi question, but in general I always look at things equally from the viewpoints of all people, it is all the same to me what language or origin they represent. Everyone should have the same rights in the same country. Well, the rights should be equal, but small ones should be protected and I’m sure the Parliament does that. Minorities, whoever they are, must be protected, that’s a different thing. I see this as an archaeological issue, I don’t consider archaeology a part of power politics or politics in general, it is a pretext. (A 12).

The interviews reflect an attitude that minorities should have some special rights to protect them, but at the same time, archaeology should stay away from such concerns and concentrate on distanced scientific thinking. The reasoning seems to be that if prehistorical finds from the present Sámi territory are interpreted “as Sámi”; then, archaeology is used as an extension for something, that is, a political tool. Yet, this is how prehistoric finds have been employed in Finland, and around the globe, to build national narratives.

It is noticeable that interviewees generally tended to avoid direct references to Sámi issues and instead stressed the need to be generally impartial and consider all the different viewpoints—and in the process rendering ethnicity either irrelevant or radically political. Such views, as Ojala has observed, are typical of people who do not have to encounter ethnicity-related depreciation or contradiction (Ojala 2009, p. 54).

This is, of course, quite contrary to the conceptions of research concerning the Sámi. In August 2017, the Finnish Sámi Parliament released guidelines for the research of Sámi cultural heritage and traditional knowledge. These new guidelines that apply to archaeologists, for example, are based on free, prior and informed consentFootnote 13 and Akwé: Kon guidelines (SCBD 2004). This means that all archaeological research and projects, for example, must apply for research permission from the Sámi Parliament and the Sámi community whose heritage or area the research concerns. In the case of the Skolt Sámi, the application must be done to the Siid sobbar administrative organ, that is, the Village Council. As a significant statement of cultural self-administration, the Sámi Parliament has the right to reject the application (Sámi Parliament 2017).

A similar reflection of Sámi self-determination is the Sámi Cultural Environment Unit in the Siida museum, Inari, mentioned in the beginning of the article. This is one indication that the rights of indigenous people are increasingly taken into account in Finnish cultural heritage circles, and simultaneously, the Sámi Parliament is increasingly demonstrating its will to take control over cultural heritage in the land of the Sámi. The results of these developments remain to be seen.

Conclusions

Although the study of ethnicity from archaeological material is difficult, the interviews suggest that this may not be the main reason why it is little discussed in Finnish archaeology. Rather, the theoretical and methodological challenges seem secondary to non-scientific issues, particularly the dispute on the definition of the Sámi and indigenous politics. The interviews indicate that a fear of becoming involved in political games makes repatriation an unpleasant subject for many Finnish archaeologists. A strict separation of politics from science can be interpreted as a means of dissociating archaeology from questions of identity instead of engaging with them. The idea of “pure science” is founded on the belief that archaeological knowledge could be exact, although the interpretative character of science has long been recognized in history and archaeology. A concern for “pure science” does not really feature quite so prominently in the general archaeological discourse in Finland, which leads one to believe that it serves as something of an excuse to avoid discussing such difficult topics as (Sámi) ethnicity and politics.

While most interviewees were wary of political involvement, one reflected, “Archaeologists should be more here and now, perhaps even politically involved in a certain way so as to make it meaningful. Maybe we have not practiced the kind of archaeology that has a meaning in the present, we are instead doing archaeology that has something to say about the past” (A 1). When archaeology’s character as a “purely scientific” pursuit is overly emphasized, it may be forgotten that archaeological finds and the past are meaningful in other ways for other groups of people; archaeology is not only the domain of archaeologists. The past is a part of the present to Sámi communities, for instance, and has other than scientific values to it.

Although the interviews were conducted recently, colonialist legacies are discernible in the ways the Sámi and Sápmi are talked about, although this is undoubtedly unintentional and merely reflects the deep embedding of colonialist ideas in archaeology and western society (see further, e.g. Lehtola 2015a, p. 23; Ojala and Nordin 2015, p. 121). Archaeological education in Finland may not provide a sufficient understanding of indigenous issues, as some interviewees also observed. This, combined with a genuine confidence in “pure science” and in some ways “traditionalistic” tendencies, especially among older generations of Finnish archaeologists, and particularly in the heritage administration sector, creates a setting where repatriation questions do not have much breathing space. In other words, Finnish archaeology still seems to carry the burden from the earlier days of the profession in the form of the implicitly nationalist general framework of archaeology, or perhaps rather the more general idea of the “unity” of Finns and Finland, and the fear of ethnicity, due to its association with the atrocities of the Second World War and political uses of archaeology (Nuñez 2011, p. 93). This aspiration for apolitical, “clinical” archaeology is probably partly derived from the ideals of processual archaeology which, along with culture-historical archaeology, has been quite influential in Finnish archaeology until recently.

There are also voices within the establishment of the Finnish museum world that advocate neutral and apolitical engagements with the past. The Secretary General of the Finnish Museums Association just recently emphasized the right of museums to function as neutral and objective institutions dedicated to the study, preservation and presentation of indigenous cultures, with a reference to the shared origins of all cultures. He urged museums to function as opponents to the tendencies towards exclusive cultural self-determination (Levä 2018). On the other hand, however, it is also common nowadays that Finnish archaeologists actively engage and collaborate with non-professionals in fieldwork, give public lectures for locals and communicate with the public through social media (Herva 2016a; 2017). Likewise, ethical questions have been of increasing interest in the last few years and were very much on the surface in the Advances in Sámi Archaeology conference in Inari in 2018.

The interviews conducted for this study propose that the idea of repatriating archaeological materials from the Sámi territory and giving the Sámi (institutions) power over heritage management is met with a degree of suspicion among Finnish archaeologists. The primary outspoken concern was whether the materials would be accessible if they were governed by the Sámi; the archaeologists interviewed thought that they and their work might become hostages to political debates. There was concern that the mere geographical relocation of the material would make research more difficult (which interestingly disregards the fact that archaeological research in Finland is not limited to Helsinki), but also a concern that the Sámi governance of the material would be more political and less impartial than in the hands of Finnish institutions. This kind of fear and opinions are not exclusive to Finnish archaeology, as similar opinions appeared in the USA before and after NAPGRA.Footnote 14 However, there have also been successful co-operation projects based on respect, partnership, relationships of trust and dialogue that must include everyone, for example (Cooper 2000; Dongoske 1996; Goldstein and Kintigh 2000; Gulliford 1992; Mihesuah 2000; Zimmerman 1996).

Genuine as the concerns of Finnish archaeologists over repatriation and its impact undoubtedly are, they also reflect the colonialist structures of Finnish archaeology. According to Kuokkanen (2007), a critical mapping and analysis of the forms and influences of colonialism comprise the basis for decolonization. In recent years, the Sámi parliament and the Sámi Museum Siida have clearly shown their will to take a stronger role in the administration of archaeological heritage. This changing situation makes it possible, indeed unavoidable, for Finnish archaeology to engage more seriously with indigenous issues. This necessitates a move from the culture of prudence and avoidance to positive action and true collaboration, which in turn can be expected to lead to a deeper understanding of the Sámi past and its multiple meanings.

Notes

Bååstede was a result of a repatriation project between Norwegian Museum of Cultural History, Museum of Cultural History and the Sámi parliament of Norway.

Until 2018 under the name National Board of Antiquities.

According to the letter of intent considering repatriation, the National Museum of Finland engaged to return the objects, once the Sámi Museum Siida had secure placement for them. This became true when the Finnish government affirmed the funding for the renovation and enlargement for the Siida museum. The first part of the large collection, 75 objects collected by Niillas-Jon Juhán (Oivoš-Johán) or Johan Nuorgam in 1930 s, was transferred to Siida in March 2018 to be presented in the exhibition Johan Nuorgam—A Sámi Cultural Broker that also marked the 20th anniversary of Siida.

The resulting audiotapes are stored in the Sámi Culture Archive, University of Oulu. I have translated the quotes myself. The translations and the codes for interviewees are meant to guarantee the anonymity of my informants.

Sámi museums in Norway like Gaaltije in Staare (Östersund), Árran in Divtesvuotna (Tysfjord), Saemien sijte in Snåase (Snåsa) in Ájtte Sámi Museum in Johkamohki (Jokkmokk) Sweden and Sámi Museum Siida in Aanaar (Inari) Finland) (see e.g. Nordberg and Fossum 2011) as well as a few individual archaeologists (Barlindhaug 2012) have practiced indigenous archaeology.

Since 2018 The Finnish Heritage Agency.

Savo is a region in Eastern Finland with a special dialect; however, they are ethnically Finnish.

Lapland is the largest and most Nordic region of Finland. It consists of 21 municipalities. Sápmi, the Sámi home area, is defined in the constitution and consists of Aanaar (Inari), Eanodat (Enontekiö), Ohcejohka (Utsjoki) municipalities and most northern part of Soađegilli (Sodankylä) municipality.

A notion has become established in Finnish archaeology that the actual Sámification is not visible in archaeological material until ca. 700/800 A.D., when the so-called rectangular hearths appeared in archaeological material (e.g. Hamari 1998, p. 74; Carpelan 2006, p. 81). Before that, there is a period of ca. 500 years in the archaeological material, called the void period (Zachrisson 1993, p. 179; Storli 1986, p.49). Dating nevertheless indicates that settlement continued, but the lack of archaeological material hinders research (e.g. Carpelan 2000, p. 34; 2003, p. 60; 2006pp. 80–81; Huurre 1985, p. 35; 1998, pp. 346–349). As some of my informants pointed out (A5 and A10), the question of the lack of archaeological material is probably an illusion, but the subject would need a lot of money and time to be studied. So, research or lack of it can create an understanding about voids in settlement (Brännström 2018). In general, archaeology as a western science in problematic in Sápmi, since in the Sámi culture it has traditionally been considered not desirable to leave traces of land use or inhabitance (See ,e.g. Magga and Ojanlatva 2013).

The interviewee refers to the views of Ante Aikio, who has claimed that the development of the Sámi language into a separate language took place later than assumed before; he places the Sámi ethno-genesis as late as about the Common Era (AD 0) (Aikio 2012).

The dispute stems from the 1995 Sámi Parliament law, where the Sámi definition gave an opportunity to apply to the electoral register of the Sámi Parliament if any of the applicant’s ancestors had been a member of a Lapp village centuries earlier. Admission to the electoral register became desirable at the stage when the discussion about ratifying the ILO convention and the related self-determination and land rights started. Because the convention was connected with the rights of the historical Lapp villages, historical research became an important part of the discussion (Lehtola 2015b, pp. 47 and 65).

FPIC is defined by United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) see http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6190e.pdf.

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990).

References

Antiquities Act. (1963). Finlex 259/1963. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/1963/19630295. Accessed July 9, 2018.

Aikio, A. (2012). An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory. A linguistic map of prehistoric Northern Europe. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

Aspelin, J. R. (1885). Suomen asukkaat pakanuuden aikana. Helsinki.

Atalay, S. (2006). Indigenous archaeology as decolonizing practice. American Indian Quaterly/Summer and Fall 2006. (Vol. 30, No 3, 4, pp. 280–304).

Äyräpää, A. (1937). Uusinta muinaislöytösatoa Oulun läänistä. Jouko III. Helsinki, (pp. 35–71).

Äyräpää, A. (1953). Kulturförhållandena i Finland före finnarnas invandring.

Barlindhaug, S. (2012). Mapping complexity. Archaeological sites and historic land use extent in a Sámi community in Arctic Norway. Fennoscandia Archaeologica, XXIX.

Bergstøl, J. (2009). Samisk og norsk arkeologi. Historieproduksjon, identitetsbygging eller politikk? Primitive tider 2009, 11. http://folk.uio.no/josteinb/Artikler/Samisk%20arkeologi%20og%20politikk.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2011.

Brännström, M. (2018). Archaeology and Sámi land rights. A paper presented at the conference “Advances in Sámi Archaeology”, 6–8 June 2018 in Inari, Finland.

Carpelan, C. (1966). Juikenttä. En sameboplats från järnåldern och medeltid. Norrbotten: Sameslöjd. Luleå: Norrbottens läns hembygdsförenings årsbok 1967, (pp. 67–76).

Carpelan, C. (1975). Saamelaisten ja saamelaiskulttuurin alkuperä arkeologin näkökulmasta. Lapin tutkimusseuran vuosikirja XVI. Rovaniemi, 1975, 3–13.

Carpelan, C. (1993). Comments on Sámi Viking Age Pastoralism—or the fur trade reconsidered. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 26, 22–26.

Carpelan, C. (2000). Saamelaisuuden kulttuurinen tausta. In K. Näkkäläjärvi & J. Pennanen (Eds.), Siidastallan - Siidoista kyliin (pp. 30–35). Kustannus Pohjoinen: Jyväskylä.

Carpelan, C. (2002). Arkeologiset löydöt aikaportaina. In: R. Grünthal, ed. Ennen, muinoin. miten menneisyyttämme tutkitaan. Tietolipas 180. Helsinki: SKS, (pp. 188–208).

Carpelan, C. (2003). Inarilaisten arkeologiset vaiheet. Teoksessa Lehtola, V-P. (toim.) Inari – Aanaar. Inarin historia jääkaudesta nykypäivään. Painotalo Suomenmaa Oulu, 2003, 28–95.

Carpelan, C. (2006). Etnicitet, identitet, ursprung? Exemplet samerna. In Herva, V-P. (Ed.) People, Material culture and environment in the North. Proceedings of the 22nd Nordic Archaeological Conference University of Oulu, 18–23 August 2004. Studia humaniora ouluensia 1. Gummerrus kirjapaino Oy 2006. (pp. 75–82).

Carpelan, C. (2008). Arkeologia ja kielten historia. In P. Halinen, M. Immonen, & M. Lavento (Eds.), Johdatus arkeologiaan (pp. 313–324). Gaudeamus: Helsinki University Press.

Carr, D. D. (1986). Narrative and the Real World. An Argument for Continuity. History and Theory. Middletown: Wesleyan university (Vol. 15, pp. 117–131).

Cooper, K. C. (2000). Spirited Encounters: American Indians Protest Museum Policies and Practices. Landham: AltaMira Press.

Dongoske, K. E. (1996). The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act: A new beginning, not the end, for osteological analysis—A hopi perspective. American Indian Quarterly, 20(2), 287–296.

Fewster, D. (2006). Visions of Past Glory: Nationalism and the Construction of Early Finnish History. Doctoral dissertation, March 2006. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Arts, Department of History.

Gabriel, M. (2010). Objects on the Move. The Role of repatriation in postcolonial imageries. Thesis (Ph.D.). Faculty of Social Sciences. Department of anthropology. University of Copenhagen.

Goldstein, L., & Kintigh, K. (2000). Ethics and the Reburial Controversy. In D. A. Mihesuah (Ed.), Repatriation Reader: Who Owns American Indian Remains? (pp. 180–189). Lincoln; London: University of Nebraska Press.

Gonzales-Ruibal, A. (2010). Colonialism and European archaeology. In J. Lydon & U. Rizvi (Eds.), Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology (pp. 37–47). Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Gulliford, A. (1992). Curation and Repatriation of Sacred and Tribal Objects. The Public Historian, 14(3), 23–38.

Guttorm, S. (2013). Åhren: Suomas eai dovddas sápmelaččaid iežas álbmotjoavkun. (online). http://yle.fi/uutiset/ahren_suomas_eai_dovddas_sapmelaccaid_iezas_albmotjoavkun/6779784 Accessed August 16, 2013.

Guttorm, A. (2014). Paikallisilla ihmisillä on monesti se paras tieto omasta ympäristöstään. Näkökulmia saamelaisperäisten muinaisjäännösten eettiseen hallintaan Suomessa. Thesis (MA). Giellagas-instituutti, Saamelainen kulttuuri, Oulun yliopisto.

Haggrén, G., Halinen, P., Lavento, M., Raninen, S., & Wessman, A. (Eds.). (2015). Muinaisuutemme jäljet. Gaudeamus: Suomen esi- ja varhaishistoria kivikaudelta keskiajalle. Helsinki.

Halinen, P. (1999). Saamelaiset - arkeologinen näkökulma. In: P. Fogelberg, ed. Pohjan poluilla. Suomalaisten juuret nykytutkimuksen mukaan. Bidrag tull kännedom av Finlands natur och folk. Finska Vetenskaps Societeten—Suomen Tiedeseura. Ekenäs Tryckeri, (pp. 249–281).

Halinen, P. (2011). Arkeologia ja saamentutkimus. Saamentutkimus tänään. In I. Seurujärvi-Kari, P. Halinen, & R. Pulkkinen (Eds.), Tietolipas 234 (pp. 130–176). Helsinki: SKS.

Hamari, P. (1998). Vanhemmat markkinapaikat ja Pohjois-Suomen rautakautinen asutus. Muinaistutkija. Suomen arkeologinen seura. Helsinki. (pp. 67–76).

Hamilakis, Y. (2007). From Ethics to Politics. In Y. Hamilakis & Ph Duke (Eds.), Archaeology and Capitalism: From Ethics to Politics. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Hansen, L.-I., & Olsen, B. (2014). Hunters in Transition. An Outline of Early Sámi History. The Northern World. North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. (Vol. 63). Leiden 2014.

Harlin, E.-K. (2008a). Repatriation as knowledge sharing—returning the Sámi cultural heritage. In M. Gabriel & J. Dahl (Eds.), Utimut: Past heritage—future partnerships, discussions on repatriation in the 21st Century. Copenhagen: IWGIA & the Greenland National Museum & Archives.

Harlin, E-K. (2008b). Recalling ancestral voices—Repatriation of Sámi cultural heritage. Interreg IIIA –projektin loppuraportti. http://www.samimuseum.fi/heritage/suomi/Loppuraportti/loppuraportti.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2017.

Harlin, E.-K. (2015). Query to archaeology subjects in Universities of Helsinki, stored in the Saami Culture Archive. Oulu and Turku: University of Oulu.

Harlin, E-K. & Olli, A. M. (2014). Repatriation. Political will and museum facilities. In: Arvanitis K., Tythacott, L. (Eds), Museums and restitution: New practices, new approaches. Abigdon: Routhledge.

Herva, V-P. (2016). Lapland´s dark heritage. Material heritage of German WWII military presence in Finnish Lapland. http://blogs.helsinki.fi/lapland-dark-heritage/. Accessed September 21, 2017.

Hesjedal, A. (2000). Samisk forhistorie i norsk arkeologi 1900–2000. Doctoral thesis. Institutt for Arkeologi. Universitet i Tromsø.

Hodder, I. (1991). Archaeological theory in contemporary European Societies: The emergence of competing traditions. In I. Hodder (Ed.), Archaeological theory in Europe (pp. 1–24). London: Routhledge.

Huurre, M. (1985). Lapin esihistoria. Lappi 4. Saamelaisten ja suomalaisten maa. Hämeenlinna, 1985, 11–37.

Jackson, G., & Smith, C. (2005). Living and learning on Aboriginal lands: decolonizing archaeology in practice. In C. Smith & M. Wobst (Eds.), Indigenous archaeologies: Decolonizing theory and practice (pp. 309–330). London: Routhledge.

Jones, S. (1997). The archaeology of ethnicity. constructing identities in the past and present. London: Routhledge.

Karjalainen, R. (2015). Saamen kielet pääomana monikielisellä Skábmagovat-elokuvafestivaalilla. Thesis (Ph.D.) Jyväskylän yliopisto.

Kuokkanen, R. (2007). Saamelaiset ja kolonialismin vaikutukset nykypäivänä. In: J. Kuortti, M. Lehtonen and O. Löytty, eds. Kolonialismin jäljet. Keskustat, periferiat ja Suomi. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Lehtola, V-P. (2005). The Right to One´s Own Past. Sámi cultural heritage and historical awareness. The North Calotte. In: M. Lähteenmäki and P.M. Pihlaja, eds. Perspectives on the Histories and Cultures of Northernmost Europe. Publications of the Department of History. University of Helsinki 18. Inari: Kustannus-Puntsi Publishing.

Lehtola, V.-P. (2015a). Sámi Histories, Colonialism and Finland. Arctic Anthropology, 52(2), 22–36.

Lehtola, V-P. (2015b). Saamelaiskiista. Sortaako Suomi alkuperäiskansaansa? Helsinki: Into kustannus. Latvia: Dardedze holografija.

Lehtola, V-P. and Länsman, A-S. (2012). Saamelaisliikkeen perintö ja institutionalisoitunut saamelaisuus. In: V-P. Lehtola, U. Piela and H. Snellman, eds. Saamenmaa. Kulttuuritieteellisiä näkökulmia. Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 91. Helsinki: Suomen Kirjallisuuden Seura, (pp. 13-35).

Levä, K. (2013). Kolonialismia ICOM kongresissa (online). http://museoliitto.blogspot.fi/2013/08/kolonialismia-icomn-kongressissa.html. Accessed June 22, 2017.

Levä, K. (2018). Historiapolitiikkaa ja kulttuurista omimista (online). https://museoliitto.blogspot.com/2018/06/historiapolitiikkaa-ja-kulttuurista.html. Accessed July 9, 2018.

Magga, P. & Ojanlatva, E. (2013). (Eds), Ealli biras. Elävä ympäristö. Saamelainen kulttuuriympäristöohjelma. Sámi museum—Saamelasimuseosäätiö. Vaasa: Waasa Graphics.

McGuire, R.H. (2008). Archaeology as political action. California series in public anthropology.

Meskell, L. (1998). Archaeology under fire: nationalism, politics and heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Routledge.

Meskell, L. (2018). A future in ruins. UNESCO, World Heritage, and the Dream of Peace.

Mihesuah, D.A. (2000). American Indians, anthropologist, pothunters, and repatriation ethical, religious, and political differences. In Mihesuah, D. A. (Ed.), Repatriation reader: Who owns American Indian remains? (pp. 24–54). Lincoln; London: University of Nebraska Press.

Mulk, I.-M. (1993). Comments on Sámi viking age pastoralism—or the fur trade reconsidered. Norwegian Archaeological Review, 26, 34–41.

Mulk, I-M. (1994). Sirkas: ett samiskt fångstsamhälle i förändring Kr.f.-1600 e.Kr.Arkeologiska institutionen, Universitet i Umeå. Studia archaeologica Universitatis Umensis 6.

Naum, M., & Nordin, J. (2013). Scandinavian colonialism and the rise of modernity. Small time agents in a global arena, contributions to historical archaeology. New York: Springer.

Nicholas, G. (2008). Native peoples and archaeology. Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 3, 1660–1669.

Nicholas, G. (2010). Seeking the End of Indigenous Archaeology. In H. Allen & D. Phillips (Eds.), Bridging the divide: Indigenous communities and archaeology into the 21st Century (pp. 233–252). Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Nicholas, G. (2014). Indigenous archaeology (“archaeology, indigenous). In J. L. Jackson (Ed.), Oxford bibliography of anthropology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nicholas, G., & Hollowell, J. (2010). Ethical challenges to a postcolonial archaeology: The legacy of scientific colonialism. In J. Hamilakis & P. Duke (Eds.), Archaeology and capitalism—From ethics to politics (pp. 59–82). Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Niezen, R. (2003). The origin of indigenism. Human rights and politics of identity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nordberg, E. & Fossum, B. (2011). Traditional Knowledge and Cultural Landscape. In: J. Porsanger and G. Guttorm (Eds)., Dieđut 1/2011. Working with Traditional Knowledge: Communities, Institutions, Information Systems, Law and Ethics. Writings from the Árbediehtu Pilot Project on Documentation and Protection of Sami Traditional Knowledge. Kautokeino: Sami University College (pp. 195–225).

Nuñez, M. (2011). Archaeology and the creation of Finland´s national identity. In: A. Olofsson (Ed.), Archaeology of indigenous peoples in the North. Archaeology and environment (Vol. 27). Umeå Universitet.

Nyyssönen, J. K. (2009). De finska samernas etnopolitiska mobilisering inom statliga ramar. Luleå tekniska Universitet, 2009(7), 167–178.

Odner, K. (1984). Finner og terfinner: etniske prosesser i det nordlige Fenno-Skandinavia. Oslo occasional papers in social anthropology 9.

Ojala, C-G. (2009). Sámi Prehistories: The Politics of Archaeology and Identity in Northernmost Europe. Thesis (Ph.D.) Occasional Papers in Archaeology 47. Uppsala: Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis.

Ojala, C-G. and Nordin, J.M. (2015). Mining Sápmi—Colonial Histories, Sámi Archaeology, and the Exploitation of Natural resources in Northern Sweden. Arctic Anthropology, (pp. 6–21).

Olsen, B. (1986). Norwegian archaeology and the people without (pre-) history, or: how to create a myth of a uniform past. Archaeological Review from Cambridge (Vol. 5, No.1).

Olsen, B. (1994). Bosetning og Samfunn i Finmarks forhistorie. Oslo: Universitetsforlag.

Olsen, B. J. (2016). Sámi archaeology. Post-colonial theory and Criticism. Fennoscandia Archaeologica XXXIII (pp. 215–229). Vaasa: Archaeological Society of Finland.

Pääkkönen, E. (2008). Saamelainen etnisyys ja pohjoinen paikallisuus. Saamelaisten etninen mobilisaatio ja paikallisperustainen vastaliike. Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopistokustannus.

Porsanger, J. (2018). Doložiid dutkama etihkka álgoálbmotkonteavsttas/Studies of the past and research ethics in indigenous context. A Key note paper presented at the conference “Advances in Sámi Archaeology”, 6–8 June 2018 in Inari, Finland.

Rankama, T. (1996). Prehistoric riverine adaptations in subarctic Finnish Lapland: the Teno River drainage. PhD dissertation. Brown University. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Dissertation Services.

Saarikivi, J., & Lavento, M. (2012). Linguistics and Archaeology: A Critical View of an Interdisciplinary Approach with Reference to the Prehistory of Northern Scandinavia. In: Networks, Interaction and Emerging Identities in Fennoscandia and Beyond: Papers from the conference held in Tromsø, Norway, October 13–16 2009 (Vuosikerta 265, Sivut 177–217). (Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne). Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

Sámi Parliament. (2017). Saamelaisen kulttuuriperinnön ja perinteisen tiedon hyödyntämistä koskevat menettelyohjeet. www.samediggi.fi. Accessed September 6, 2017.

Sanila-Aikio, T. (2018) Speech presented at the conference “Advances in Sámi Archaeology”, 6–8 June 2018 in Inari, Finland.

Schanche, A. (1994). Sacrificial places and their meaning in Saami society. In: D. L. Carmichael (Ed.), Sacred sites, sacred places. London: Routledge. (One world archaeology, 99-0815658-6; 23). (pp. 121–123). ISBN: 0-415-09603-0.

Schanche, A. (2000). Graver i ur och berg. Samisk gravskikk og religion fra forhistorisk til nyere tid. Karasjok: Davvi Girji OS.

Schanche, A., & Olsen, B. (1985). Var de alle nordmenn? En etnopolitisk kritikk av norsk arkeologi. I J. R. Næss (red.): Arkeologi og etnisitet, Ams-Varia 15, Stavanger (revidert utgave av Schanche og Olsen 1983).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2004). Akwé: Kon Voluntary guidelines for the conduct of cultural, environmental and social impact assessments regarding developments proposed to take place on, or which are likely to impact on, sacred sites and on lands and waters traditionally occupied or used by Indigenous and local communities. Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/akwe-brochure-en.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2017.

Simonsen, P. (1982). Veidemenn på Nordkalotten (Vol. 4). Tromsø: Stensilserie B, ISV, University of Tromsø.

Smith, L. (2004). Archaeological theory and the politics of cultural heritage. London: Routledge.

Smith, C., & Wobst, M. (2005). Indigenous Archaeologies: Decolonizing archaeological theory and practice. One World Archaeology 47. New York: Routledge.

Spangen, M., Salmi, A-K. and Äikäs, T. (2015). Sámi archaeology and postcolonial theory-an introduction. In: M. Spangen, A-K. Salmi, T. Äikäs (Eds.), Arctic anthropology (Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 1–5).

Storli, I. (1986). A review of archaeological research on Sami prehistory. Acta Borealia (Vol 3/1, pp. 43–63).

Storli, I. (1993a). Sami Viking Age Pastoralism - or “The fur trade paradigm” reconsidered. Norwegian archaeological review 1993; (Vol: 1, pp. 1–20). ISSN 0029-3652.

Storli, I. (1993b). Reply to Comments on Sami Viking Age Pastoralism - or “The fur trade paradigm” reconsidered. Norwegian archaeological review 1993; (Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 41–44). ISSN 0029-3652.

Tallgren, A. M. (1931). Suomen muinaisuus. Suomen historia I. Porvoo - Helsinki.

Tuhiwai-Smith, L. (2008). Decolonizing methodologies. Research and indigenous peoples. Zen books LTD: London. Dunedin: University of Otago Press.

Tythacott, L., & Arvanitis, K. (2014). An Introduction. In L. Tythacott & K. Arvanitis (Eds.), Museums and restitution. New practices, new approaches (pp. 1–16). Abingdon: Routledge.

Ucko, P. (2001). ‘Heritage’ and ‘Indigenous peoples’ in the 21st century. Public Archaeology, 1, 227–238.

Valkonen, S. (2009). Poliittinen saamelaisuus. Tampere: Vastapaino.

Watkins, J. (2005). Through wary eyes: Indigenous perspectives on archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 34, 429–449.

Wood, M. C. (2002). Moving towards transformative democratic action through archaeology. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 6(3), 187–198.

Yle Uutiset. (2012). Niinistön tulkinta ILO-sopimuksesta ihmetytti saamelaiskäräjillä. Uutinen, päivitetty 28.4.2012. http://yle.fi/uutiset/niiniston_tulkinta_ilosopimuksesta_ihmetytti_saamelaiskarajilla/5292038. Accessed April 3, 2012.

Zachrisson, I. (1993). A review of archaeological research on Saami prehistory in Sweden. Current Swedish Archaeology, 1, 171–182.

Zachrisson, I. (1997). Möten i gränsland: samer och germaner i Mellanskandinavien. Borås: Statens Historiska Museum.

Zimmerman, L. J. (1996). Epilogue: A new and different archeology? American Indian Quarterly, 20(2), 297–307.

Audiotapes stored in the Saami Culture Archive, University of Oulu

Interviews with A 1-A 13.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Oulu including Oulu University Hospital. I am most grateful for professors Veli-Pekka Lehtola and Vesa-Pekka Herva, who supervised this research at the University of Oulu and the anonymous reviewers for their comments that helped to improve this article. I also wish to express my gratitude to the informants that made this article possible. This study is a result of the research projects “Domestication of Indigenous Discourses? Processes of Constructing Political Subjects in Sápmi” funded by the Academy of Finland (2015–2018) and “Collecting Sápmi” funded by the Swedish Research Council (2013–1917).

Funding

Funding was provided by Suomen Akatemia (Grant No. 243018021), Vetenskapsrådet (Grant No. 421-2013-1917).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I use Northern Sámi terms in my paper, if not otherwise mentioned. Place names are written in Sámi language spoken in the area.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Harlin, EK. Sámi Archaeology and the Fear of Political Involvement: Finnish Archaeologists’ Perspectives on Ethnicity and the Repatriation of Sámi Cultural Heritage. Arch 15, 254–284 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-019-09366-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-019-09366-7