Abstract

Supracondylar fracture of the humerus is the second most common fracture in children (16.6%) and the most common elbow fracture. These fractures are classified using the modified Gartland classification. Type III and type IV are considered to be totally displaced. A totally displaced fracture is one of the most difficult fractures to manage and may lead to proceeding to open procedures to achieve acceptable reductions. Many surgeons are concerned about its outcome compared to closed procedures. We therefore performed a systematic review of the literature to investigate the existing evidence regarding functional and radiological outcomes as well as postsurgical complications of primary open compared to primary closed reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Supracondylar fracture of the humerus (SCFH) is the second most common fracture in children (16.6%) [1, 2] and the most common elbow fracture [3–6]. Two-thirds of children hospitalized because of an elbow injury have a SCFH [3, 7].

The age range is 5–7 years old. Boys have a higher incidence of this type of fracture, but the difference in comparison to girls seems to be equalizing, and higher rates in girls have actually been reported in some series [3, 8, 9].

The mechanism is usually due to a fall onto an outstretched hand with the elbow in full extension (97–99% of cases). The olecranon engages the olecranon fossa and acts as a fulcrum, while the anterior aspect of the capsule provides a tensile force on the distal part of the humerus proximal to its insertion [3].

These fractures are classified using the modified Gartland classification [10]. Type III (no cortical contact, extension of the distal fragment in the sagittal plane and rotation in the frontal plane) and type IV (described by Leitch et al. [11] as fractures with multidirectional instability) are considered to be totally displaced.

A totally displaced fracture is one of the most difficult fractures to manage because of marked swelling, difficulty in reduction and maintaining the reduction until healing takes place. This kind of fracture may be complicated by neurovascular injuries, malunion, elbow stiffness and compartment syndrome. These issues are associated with the fact that many hospitals in the world do not offer fluoroscopy, so treating these fractures may lead to open procedures to achieve acceptable reductions.

Regarding this fact, many surgeons are concerned about its outcome in comparison to the closed procedure. We therefore performed a systematic review of the literature to investigate the existing evidence regarding functional, cosmetic and radiological outcomes as well as post-surgical complications of primary open reduction compared to primary closed reduction.

Materials and methods

We performed a systematic review of the literature to identify publications dealing with functional, cosmetic and radiological outcomes in patients with totally displaced SCHFs managed with primary open reduction in comparison to primary closed reduction. An electronic search of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases (from August 1977 to October 2009) was conducted, entering the following terms and Boolean operators: “supracondylar fractures” AND “open” AND “closed reduction” AND “child”. Only papers in English were included.

Articles were considered eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) the target population consisted of children with totally displaced SCHFs; (2) each study included a comparison between primary open and primary closed reduction procedures stabilized with K-wires; (3) functional, cosmetic and/or radiological outcomes were provided; (4) post-surgical complications were described adequately.

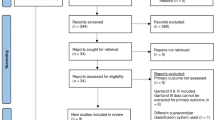

Review articles, case reports, expert opinion articles, editorials, letters to the editor, publications on congress proceedings, manuscripts with incomplete documentation of the outcomes mentioned above, details of applied procedures and unpublished series were excluded (Fig. 1).

The quality of the reviewed manuscripts was evaluated by two assessors (J-PM, J-RM). They independently classified the reviewed studies for the level of evidence [12, 13] (Table 1) and selected the appropriate studies based on the above criteria.

Data extracted from these articles were further analyzed for: (1) functional, cosmetic and radiological outcomes as well as (2) post-surgical complications according to the method of reduction.

Of the papers initially selected based on the search strategy of this study, three met the inclusion criteria. The levels of evidence of these studies were II (prospective comparative study) [6] and III (retrospective comparative studies) [1, 14]. Two hundred seven patients were included for the final analysis: 112 patients in the primary closed reduction group and 95 patients in the primary open reduction group (Table 1).

To assess the functional (loss of motion) and cosmetic (carrying angle) outcomes, we used Flynn’s criteria [15] (Table 2). To assess the radiological outcome, we included the following items: Baumann’s angle difference [3], time to union and nonunions. Post-surgical complications described were compartment syndrome, nerve/vascular injury, pin tract infection and wound issues.

Data analysis

Functional and cosmetic outcomes were assessed using a fixed-effects meta-analysis model with the meta statistical package in STATA v. 10.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) because heterogeneity was not significant in the random effects model (P value > 0.05 in all cases). Heterogeneity was measured by means of the I statistic proposed by Higgins and Thompson. The odds ratio (OR) was weighted by the inverse variance. Differences in radiological outcome as well as post-surgical complications between the open and closed reduction groups were analyzed by the chi-square test, and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We identified 164 articles after our search (Fig. 1); after applying our eligibility criteria, we had three manuscripts for systematic review and data synthesis [1, 6, 14].

The patient groups were well matched at baseline for the available demographic data. The primary closed reduction group consisted of 112 patients with a mean age of 7.3 years and a mean follow-up of 19.6 months. The primary open reduction group was comprised of 95 patients with a mean age of 7.8 years and mean follow-up of 23.16 months. A total of 207 patients were included in the analysis (Table 1). Only one article [6] reported the difference in Baumann’s angle between both groups; all three articles reported both functional and cosmetic outcomes as well as the complications described before. The majority of open reductions were done using a lateral approach (51 patients), and in 44 patients a posterior approach was used.

Studies used in the analysis of the functional and cosmetic outcomes did not show evidence of statistical heterogeneity (Figs. 2a–d, 3a–d). In both groups the functional and cosmetic outcomes were divided into their subcategories for analysis according to Flynn’s criteria (excellent, good, fair, poor).

Representative forest plot for odds of functional outcome in open reduction and pinning compared to closed reduction and pinning according to Flynn’s criteria [15]. a Functional outcome, excellent. b Functional outcome, good. c Functional outcome, fair. d Functional outcome, poor

Representative forest plot for odds of cosmetic outcome in open reduction and pinning compared to closed reduction and pinning according to Flynn’s criteria [15]. a Cosmetic outcome, excellent. b Cosmetic outcome, good. c Cosmetic outcome, fair. d Cosmetic outcome, poor

Functional outcome

Four subcategories were evaluated (excellent, good, fair and poor). A representative forest plot for odds with a 95% confidence interval of functional outcome according to Flynn’s criteria for open compared to closed reduction was used. There was no heterogeneity among the studies compared in each subcategory. Regarding the excellent subcategory, there was a statistically significant overall result in favor of open reduction (Fig. 2a) [OR: 2.32 (1.11, 4.85)]. The poor subcategory also showed statistical significance in favor of the closed reduction group (Fig. 2d) [OR: 0.19 (0.06, 0.62)]. The good and fair subcategories did not show an overall statistically significant difference [OR: 0.75 (0.28, 2.04) and OR: 1.46 (0.40, 5.34), respectively]; however, there was a tendency to good results in the closed reduction group and to fair results in the open reduction group (Fig. 2b, c).

Cosmetic outcome

As was done for the functional outcome, a representative forest plot for odds with a 95% confidence interval of cosmetic outcome according to Flynn’s criteria in open compared to closed reduction was used. In this case, none of the subcategories showed statistically significant differences: excellent [OR: 1.13 (0.61, 2.10)] (Fig. 3a); good [OR: 0.96 (0.27, 3.36)] (Fig. 3b); fair [OR: 0.78 (0.38, 1.64)] (Fig. 3c); poor [OR: 1.09(0.24, 5.07)] (Fig. 3d). However, there was a tendency to excellent results in the open reduction group.

Radiological outcome

The radiological outcome assessment included the Baumann’s angle difference and times to union and nonunion (Table 3). One study commented on the Baumann’s angle difference [6], but the other two did not. The mean difference in the primary open reduction group was 2.45° (0–6.5), and in the primary closed reduction group it was 2.32° (0–6.5). This finding was not statistically significant (P = 0.8). All three articles [1, 6, 14] commented on time to union. The mean time to union in the primary open reduction group was 4.2 weeks, whereas in the primary closed reduction group it was 4 weeks. This finding was also not statistically significant (P = 0.374). There were no nonunions reported in either groups.

All three studies mentioned complications [1, 6, 14] such as compartment syndrome, nerve/vascular injuries and infections (pin tract infection; Table 4); one commented on wound issues [1] such as wound infection and scarring problems. No cases of compartment syndrome were reported in either group. The nerve injuries reported were ulnar nerve injuries, and no vascular injuries occurred. The overall ulnar injury nerve rate was 5.79%. There were four ulnar nerve injuries in the primary open reduction group (4.2%) and eight ulnar nerve injuries in the primary closed reduction group (7.14%). However, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.828).

The overall pin tract infection rate was 5.31%. There were five cases in the primary open reduction group (5.26%) and six cases in the primary closed reduction group (5.35%). This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.994). Regarding wound issues, there was only one case of a superficial wound infection, and there were no reported cases of scar problems or avascular necrosis of the trochlea.

Discussion

Supracondylar fractures can be one of the most difficult fractures to treat [16]. The incidence rate is around 17.9% [17]. The ultimate aim of any treatment of completely displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus is the recovery of full function with no deformity or residual neurovascular deficits [1, 18–21]; this could be achieved through an anatomical reduction(decreases deformities [22]), ideally in a single intervention [19], which could be obtained using several methods, such as closed reduction and casting, closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, traction, and open reduction and internal fixation [23].

Currently, the preferred approach for the treatment of displaced pediatric supracondylar fractures is closed reduction and percutaneous pinning [14, 19]; however, this fails in up to 25% of patients [24] and requires remanipulation because of inadequate reduction or malpositioning of wires in 1–7% of patients [20].

Often, intraoperative closed reduction attempts do not yield satisfactory alignment of the fracture [25]. Inadequate reduction in the coronal plane can produce deformities such as cubitus varus (the most common complication [16, 17] in up to 60% [17]) or valgus and in the sagittal plane malrotation, angulation or translation, which can cause functional losses [19]. It also can be associated with inadequate or improper fixation.

As a consequence of this issue and because the treatment goal is anatomical reduction [26], some authors have advocated open reduction and pinning as an alternative treatment [14, 27–30]. Traditionally, it has been reserved for cases with primary vascular or neural disruption, open fractures, signs of Volkmann’s ischemia, failure of closed reduction and severe swelling not allowing acceptable reduction [14, 16, 18, 21, 22, 26]. This means that a certain portion of the displaced fractures cannot be reduced with the closed method [22], with the conversion rate to open reduction being between 3 and 46% [14, 25, 31].

Some authors believe that open reduction (Fig. 4a–d) may have worse results than closed reduction [25] as loss of motion, myositis ossificans and infection are possible complications. However, in the majority of studies, the patients in the open reduction groups had severely displaced fractures [21, 24], thus showing a more difficult pattern [1], which could explain the poorer results [14].

A 5-year-old boy who sustained a casual fall. He presented to the emergency room with pain and functional impotence of his left elbow. There was no neurovascular involvement. After two failed closed reduction attempts, an open reduction and pinning with a 02 Kw lateral configuration using a lateral approach was performed. a Pre-surgical antero-posterior view of a severely displaced Gartland type III fracture. b Pre-surgical lateral view of a severely displaced Gartland type III fracture. c Post-surgical antero-posterior view with a lateral pinning configuration showing that both columns were engaged and the divergence of the wires, making a stable construct. d Post-surgical lateral view with a lateral pinning configuration

Many surgeons are concerned that this may lead to the acceptance of suboptimal fracture alignment. Controversy exists about the influence of open exposure on the functional and cosmetic outcomes as well as its complications [25, 31]. Therefore, the analyzed data are from studies in which a primary open reduction compared to a closed reduction was performed to avoid this issue.

There is no agreement among authors with regard to the functional outcome according to Flynn’s criteria; we found a statistically significant overall result in favor of open reduction and pinning in the excellent subcategory as well as a statistically significant result in favor of closed reduction and pinning in the poor subcategory. This finding could be explained by the better anatomical reduction obtained using an open approach. Kumar et al. [32] treated 44 patients with open reduction and pinning and found that 95% had a satisfactory outcome. Ay et al. [33] described the results in 61 patients treated with a transverse anterior cubital approach for open reduction and pinning; the results were excellent in 72.2% and good in 27.8%. Cramer et al. [26] found that open reduction itself does not appear to cause stiffness and decrease strength. On the other hand, Reitman et al. [23] found excellent results for only a 55% of elbows. Ababneh et al. [21] concluded that the best results were achieved by closed reduction and pinning as judged by the highest incidence of excellent results and the lowest incidence of poor results. Aktekin et al. [25] found that patients treated with closed reduction and pinning had better function and a greater range of movement of the elbow. Pirone et al. [34] suggested that open reduction increased the risk of stiffness. We have to take into account that these worse results are because open reduction in those studies was performed after a closed reduction attempt, meaning that the open reduction group was made up of patients with a more difficult pattern of fractures.

In the analysis of the cosmetic outcome, we did not find any subcategory with a statistically significant result. This finding agrees with the literature. Ozkoc et al. [14] found that the cosmetic outcome did not differ between both groups. Kazimoglu et al. [1] also determined that there was no difference between both groups with regard to cosmetic evaluation.

We did not find any statistically significant result regarding the radiological outcome. No cases of nonunion were reported, and the distal humerus was an uncommon location. Time to union could be a concern for some surgeons when making a decision regarding the method of reduction. In light of our findings, we think that open reduction should not be considered an issue. There was no significant difference regarding the difference in Baumann’s angle between the groups. This finding correlates with the idea that coronal plane malreduction is not an issue regarding the method of reduction.

No cases of compartment syndrome were reported. We think that although this complication occurs infrequently, it should be taken into account because of its fatal consequences if left untreated. Neurological injury is more prevalent in cases of highly displaced fractures in the pre-surgery setting [23]. We found an overall ulnar nerve injury rate of 5.79% after surgery; this correlates with the rates reported in the literature [14, 23, 25]. In the open reduction group, the rate was 4.2%, and in the closed reduction group, it was 7.14%. This difference was not statistically significant. Similar findings were reported by Kazimoglu et al. [1] with a 9.7% rate in the closed reduction group and a 5.4% rate in the open reduction group. Nerve injury in the open reduction group could be explained by a traction mechanism [14], and this mostly recovers spontaneously without complications [1]. The pin tract infection rate reported in the literature ranges from 2 to 7% [14, 25]. Pirone et al. [34] suggested an increased risk of infection after open reduction, and this issue is a concern for many orthopedic surgeons. We found an overall rate of 5.31% and a lower rate in the open reduction group (5.26% vs. 5.35%). However, this finding is not statistically significant. These infections usually resolve with pin removal [25]. We think open reduction by itself does not increase the risk of infection. Wound infection is not a concern when doing an open approach; as we saw in the one case in which this occurred in our study, the infection resolves with antibiotics. Aktekin et al. [25] reported two cases of avascular necrosis of the trochlea. We did not find any cases, and because of its infrequency, this should not be a concern.

This study has some limitations. The small number of studies selected for analysis was a consequence of the strict inclusion criteria used. This allowed us to have a more valuable analysis of the effect of open reduction by itself on the different parameters described; however, the number of patients for analysis decreased. A second limitation is the inclusion of different approaches in the open reduction group, even though we think this fact is not crucial for our analysis. This is in keeping with the report by Sibly et al. [29], who did not find a correlation between stiffness and the surgical approach, and Koudstaal et al. [35], who compared different surgical approaches with no statistically significant differences.

Conclusion

Open reduction and pinning alone should not be a concern for obtaining an anatomical reduction in severely displaced supracondylar fractures in children, as in this study this technique has been shown to have the highest probability of excellent functional results and lowest of poor results.

We recommend starting with a closed reduction technique unless some special circumstances are present; if an anatomical reduction cannot be obtained after one or two closed attempts, an open reduction should be performed because repetitive manipulations could result in joint stiffness [1] and transient neuropraxia [24] (Fig. 5). Obtaining an adequate anatomical reduction favors excellent to good functional and cosmetic outcomes as well as fewer complications.

References

Kazimoglu C, Cetin M, Sener M, Agus H, Kalanderer O (2009) Operative management of type III extension supracondylar fractures in children. Int Orthop 33:1089–1094

Battagila TC, Armstrong DG, Schwend RM (2002) Factors affecting forearm compartment pressures in children with supracondylar fractures of the humerus. J Pediatr Orthop 22:431–439

Omid R, Choi PD, Skaggs DL (2008) Supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:1121–1132

Otsuka NY, Kasser JR (1997) Supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 5:19–26

Cheng JC, Ng BK, Ying SY, Lam PK (1999) A 10-year study of the changes in the pattern and treatment of 6,493 fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 19:344–350

Kaewpornsawan K (2001) Supracondylar humeral fractures: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Orthop B 10:131–137

Kasser JR, Beaty JH (2006) Supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus. In: Beaty JH, Kasser JR, Wilkins KE, Rockwood CE (eds) Rockwood and Wilkins’ fractures in children, 6th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia. pp 543–589

Cheng JC, Lam TP, Maffulli N (2001) Epidemiological features of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in Chinese children. J Pediatr Orthop B 10:63–67

Farnsworth CL, Silva PD, Mubarak SJ (1998) Etiology of supracondylar humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 18:38–42

Gartland JJ (1959) Management of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet 109:145–154

Leitch KK, Kay RM, Femino JD, Tolo VT, Storer SK, Skaggs DL (2006) Treatment of multidirectionally unstable supracondylar humeral fractures in children. A modified Gartland type-IV fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:980–985

Bhandari M, Giannoudis PV (2006) Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it is not. Injury 37:302–306

Ryan R, Hill S, Broclain D, Horey D, Oliver S, Prictor M (2009) Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. Study Quality Guide. Available at: http://www.latrobe.edu.au/cochrane/resources.html. Accessed 22 Nov 2009

Ozkoc G, Gonc U, Kayaalp A, Teker K, Peker TT (2004) Displaced supracondylar humeral fractures in children: open reduction vs. closed reduction and pinning. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 124(8):547–551

Flynn JC, Matthews JG, Benoit RL (1974) Blind pinning of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 56:263–272

Yusof A, Razak M, Lim A (1998) Displaced supracondylar fracture of humerus in children–comparative study of the result of closed and open reduction. Med J Malaysia 53 (Suppl A):52–58

Sadiq MZ, Syed T, Travlos J (2007) Management of grade III supracondylar fracture of the humerus by straight–arm lateral traction. Int Orthop 31:155–158

Mulhall KJ, Abuzakuk T, Curtin W, O’Sullivan M (2000) Displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Int Orthop 24(4):221–223

Turhan E, Aksoy C, Ege A, Bayar A, Keser S, Alpaslan M (2008) Sagittal plane analysis of the open and closed methods in children with displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus (a radiological study). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 128(7):739–744

Barlas K, Baga T (2005) Medial approach for fixation of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Acta Orthop Belg 71(2):149–153

Ababneh M, Shannak A, Agabi S, Hadidi S (1998) The treatment of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. A comparison of three methods. Int Orthop 22(4):263–265

Oh CW, Park BC, Kim PT, Park IH, Kyung HS, Ihn JC (2003) Completely displaced supracondylar humerus fractures in children: results of open reduction versus closed reduction. J Orthop Sci 8(2):137–141

Reitman RD, Waters P, Millis M (2001) Open reduction and internal fixation for supracondylar humerus fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 21(2):157–161

Aronson DC, van Vollenhoven E, Meeuwis JD (1993) K-wire fixation of supracondylar humeral fractures in children: results of open reduction via a ventral approach in comparison with closed treatment. Injury 24(3):179–181

Aktekin CN, Toprak A, Ozturk AM, Altay M, Ozkurt B, Tabak AY (2008) Open reduction via posterior triceps sparing approach in comparison with closed treatment of posteromedial displaced Gartland type III supracondylar humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop B 17(4):171–178

Cramer KE, Devito DP, Green NE (1992) Comparison of closed reduction and percutaneous pinning versus open reduction and percutaneous pinning in displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Orthop Trauma 6(4):407–412

Kotwal PP, Mani GV, Dave PK (1989) Open reduction and internal fixation of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus. Int Surg 74:119–122

Mulhall KJ, Abuzakuk T, Curtin W, O’Sullivan M (2000) Displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Int Orthop 24:221–223

Sibly TF, Briggs PJ, Gibson MJ (1991) Supracondylar fractures of the humerus in childhood: range of movement following the posterior approach to open reduction. Injury 22:456–458

Mehlman CT, Strub WM, Roy DR, Wall EJ, Crawford AH (2001) The effect of surgical timing on the perioperative complications of treatment of supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83:323–327

Alonso LM (1972) Bilaterotricipital approach to the elbow. Its application in the osteosynthesis of supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children. ActaOrthop Scand 43:479–490

Kumar R, Kiran EK, Malhotra R, Bhan S (2002) Surgical management of the severely displaced supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children. Injury 33:517–522

Ay S, Akinci M, Kamiloglu S, Ercetin O (2005) Open reduction of displaced pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures through the anterior cubital approach. J Pediatr Orthop 25:149–153

Pirone AM, Graham HK, Krajbich JI (1988) Management of displaced extension-type supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 70:641–650

Koudstaal MJ, De Ridder VA, De Lange S, Ulrich C (2002) Pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures: the anterior approach. J Orthop Trauma 16:409–412

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pretell-Mazzini, J., Rodriguez-Martin, J. & Andres-Esteban, E.M. Does open reduction and pinning affect outcome in severely displaced supracondylar humeral fractures in children? A systematic review. Strat Traum Limb Recon 5, 57–64 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11751-010-0091-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11751-010-0091-y