Abstract

Inspired by the goal of making marketplaces more inclusive, this research provides a deeper understanding of consumer vulnerability dynamics to develop strategies that help reduce these vulnerabilities. The proposed framework, first, conceptualizes vulnerability states as a function of the breadth and depth of consumers’ vulnerability; then, it sketches a set of vulnerability indicators that illustrate vulnerability breadth and depth. Second, because the breadth and depth of vulnerability vary over time, the framework goes beyond vulnerability states to identify distinct vulnerability-increasing and vulnerability-decreasing pathways, which describe how consumers move between vulnerability states. In a final step, the framework proposes that organizations can (and should) support consumers to mitigate vulnerability by helping consumers build resilience (e.g., via distinct types of resilience-fueling consumer agency). This framework offers novel conceptual insights into consumer vulnerability dynamics as well as resilience and provides avenues for future research on how organizations can better partner with consumers who experience vulnerabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Calls for marketplaces to be more inclusive are increasing in frequency and vigor (e.g., Aksoy et al., 2019; Boenigk et al., 2021; Field et al., 2021). For example, Fisk et al., (2018, p. 851) emphasize that service systems need to better include the full diversity of people so that “all customers have the ability to receive the same level of value that is inherent in a marketplace exchange.”Footnote 1 However, to make this notion a reality, marketers must better understand the range of vulnerabilities that diverse consumers may experience in order to (co-)create strategies—in partnership with consumers—to help reduce, or ideally eliminate these vulnerabilities.

Consumer vulnerability is not a new topic in marketing (e.g., Dunnett et al., 2016). Baker et al. (2005) first defined consumer vulnerability, and Shultz and Holbrook (2009) discussed the paradoxical relationship between how marketing both reduces and contributes to consumer vulnerability. Building from those foundations, Hill and Sharma (2020) reviewed academic and applied definitions of consumer vulnerability to develop a framework that organized antecedents and consequences of consumer vulnerability and evolved the definition of vulnerability as “a state in which consumers are subject to harm because their access to and control over resources is restricted in ways that significantly inhibit their abilities to function in the marketplace” (p. 554).Footnote 2 Salisbury et al., (2023, p. 659) extended this definition to encapsulate the idea that consumer vulnerability is a “dynamic state that varies along a continuum as people experience more or less susceptibility to harm, due to varying conditions and circumstances.” Inspired by these insights, our examination aims to further expand the conceptualization of consumers’ lived vulnerability experiences and their dynamics, so that organizations can better partner with and support consumers in reducing (and, ideally, preventing) their vulnerability.

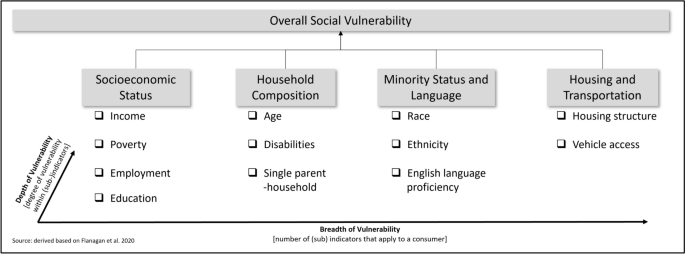

Specifically, we introduce the concept of consumer vulnerability pathways, which capture how consumers move between different vulnerability states (i.e., moving from a nonvulnerable state into a vulnerable state, and vice versa). We conceptualize an individual’s vulnerability state as a function of both the breadth and depth of their vulnerability. Breadth is the number of different factors (e.g., income, age, disabilities, race, language proficiency) that contribute to the individual’s vulnerability, and depth is the degree of vulnerability within each of those factors. With this backdrop of consumer vulnerability experiences, we then offer novel insights into how marketers can support consumers by developing more inclusive, equitable environments and by proactively helping to reduce consumers’ vulnerability and build resilience.

This research contributes to the marketing literature by, first, incorporating concepts from disaster research (e.g.,Vázquez-González et al., 2021) that allow us to introduce a novel conceptualization of vulnerability states as the interplay of two dimensions: vulnerability breadth and depth. Because the notion of vulnerability dynamics implies change over time, these dimensions are a crucial conceptual prerequisite to explore dynamics as variations in breadth and depth. Drawing from disaster research (e.g., Beccari, 2016), we then illustrate vulnerability indicators to better elucidate the concepts of breadth and depth for marketers; these insights expand the existing realm of marketing indicators to emphasize the fact that marketers’ standard measures of vulnerability may not always coincide with the consumers they are serving.

Second, grounded in the idea that breadth and depth of vulnerability can vary, we build on life course theory in sociology (e.g., Bernardi et al., 2019; Elder, 1995) to identify distinct vulnerability pathways; specifically, our framework goes beyond discrete vulnerability states to incorporate vulnerability-increasing and vulnerability-decreasing pathways. These pathways reveal novel insights for marketers into the nature of consumers’ vulnerability journeys, thereby recognizing that vulnerability is a lived experience and that no case is truly the same (Shaw et al., n.d.). Understanding that a consumer’s vulnerability state is a function of her vulnerability pathway is crucial for marketers because—although consumers might currently be in a similar vulnerability state—their pathways toward that state can be drastically different and, therefore, might require organizations to serve consumers in unique ways.

Third, we draw on recent research in psychology that conceptualizes resilience as a dynamic construct (e.g., Masten et al., 2021) to identify how marketers can proactively assist consumers in reducing their vulnerability and in building their resilience. Specifically, we propose that organizations demonstrate the notion of “service thinking” (Alkire et al., 2023) such that they intentionally engage with and support consumers in developing resilience capacity through factors such as social support, problem-solving, and through promoting consumers’ agency to anticipate, prevent, prepare, adapt, and transform (Manyena et al., 2019; Vázquez-González et al., 2021). Against the background of our conceptual framework, we conclude with a discussion of future research directions for marketing intended to help organizations better serve consumers experiencing vulnerability.

Conceptual evolution of vulnerability dynamics

While there has been a fair amount of research into vulnerability in marketing in terms of its antecedents and consequences (for reviews see Basu et al., 2023; Hill & Sharma, 2020; Riedel et al., 2022), only recent examinations in the marketing literature consider the dynamism of vulnerability. Hill and Sharma (2020) first discussed it by considering that resource/control combinations change over time and that consumers’ coping mechanisms also fluctuate. Salisbury et al. (2023) made the dynamic nature of (financial) vulnerability even more central to their model by considering multiple time periods, thereby recognizing that financial resource access can lead to immediate or lagged impacts on vulnerability; the authors also recognize the presence of inflection points, or times when a consumer’s vulnerability shifts significantly due to changing circumstances, life events, or consumer choices. Blocker et al. (2023) provide insights into vulnerability as they examine how shock and slack impact the ways in which resources are developed, aggregated, maintained, or lost over time; this then creates resource trajectories that are an “aggregate bundle of fluctuating resources relative to one’s overall resource sufficiency over time” (p. 499). Table 1 presents key tenets of these papers on vulnerability dynamics in marketing.

Building from this prior research, we draw on life course theory from sociology to deepen our conceptual understanding of vulnerability dynamics that will be insightful for managers as they strive to help consumers reduce their vulnerabilities. The life course represents the “steady flow of an individual’s actions and experiences, which modify domain-specific biographical states and affect individual wellbeing over time” (Bernardi et al., 2019, p. 2). Adopting a pointedly dynamic perspective, life course theory (LCT) aims to explain “how biological, psychological, and socio-cultural factors act independently, cumulatively, and interactively” to shape life journeys (Hutchison, 2019, p. 351) and transitions of people from one biographical state to the next (Bernardi et al., 2019). Regarding these transitions, LCT predicts that what happens in one period of life is connected to what happens in subsequent periods.

A life course perspective allows a particularly deep understanding of vulnerability (Ferraro & Schafer, 2017; Hanappi et al., 2014) for multiple reasons: first, it underscores that vulnerability “processes may be very different in relation to when (at what age, historical period, or cohort), where (in specific groups, institutions, welfare regimes, normative climates, etc.), and for whom (heterogeneity of individuals, social origins, gender, etc.)” vulnerability processes emerge (Spini et al., 2017, p. 20). Second, LCT underscores that vulnerability is an inherently dynamic process during which risk exposure changes and the level and range of available resources also fluctuate. A life course perspective helps capture these systemic and dynamic properties of vulnerability, because LCT accounts for three realities related to vulnerability (Spini et al., 2017, p. 9): “(1) The diffusion of stress and the mobilization of resources is multidimensional: it occurs across life domains;” (2) it is multilevel: it occurs between the individual, group, and collective levels; and (3) “it is multidirectional: it is by definition dynamic and develops over time over the life course.” Drawing from these central tenets of LCT, we develop a conceptual framework of vulnerability dynamics that includes vulnerability states and vulnerability pathways. This framework leads us to propose how organizations can deliberately and proactively help reduce consumer vulnerabilities and increase consumer resilience.

Vulnerability states as a function of vulnerability breadth and depth

Vulnerability dynamics reflect change over time; therefore, a conceptual prerequisite is to explore dynamics across vulnerability states. Against this background, we conceptualize a consumer’s vulnerability state as a function of both the breadth and depth of their vulnerability. While breadth represents the number of indicators that contribute to the consumer’s vulnerability, depth represents the degree of vulnerability within each of those factors.

Individual vulnerabilities are influenced by a variety of factors that include the psycho-physiological functioning (e.g., biological profiles/genetics) and dispositions of the person (e.g., personality traits, values, attitudes);Footnote 3 individual vulnerability also varies based on a person’s distinct life domains and contexts (e.g., those related to employment or family configurations) and of socio-structural achievements, barriers, and characteristics (e.g., education, social status) (Fineman, 2008; Luna, 2019; Spini et al., 2017). Finally, individual vulnerability is a function of the types and amounts of resources a person can invest and any special legal rights or social privileges (e.g., citizenship, gender) they can leverage (Bernardi et al., 2019).

To help organizations better understand these vulnerability factors and to help them construct corresponding vulnerability indicators (e.g., in financial /healthcare settings), we integrate LCT with disaster management research.Footnote 4 In light of increasing frequency and impact of crises (e.g., natural disasters, military conflicts), a growing literature aims to quantify social vulnerabilities, which are defined “in terms of the characteristics of a person or community that affect their capacity to anticipate, confront, repair, and recover from the effects of a disaster” (Flanagan et al., 2018, p. 34). One prominent approach to quantifying vulnerabilities is composite indicators (Asadzadeh et al., 2017; Spielman et al., 2020), which—ideally guided by a conceptual framework—aggregate underlying sub-indicators of vulnerability into an overarching composite indicator (similar to the concept of a higher-order construct). Because indicators of vulnerability often do not occur in isolation but together, composite indices typically combine variables across multiple domains. Although there is currently no generally agreed-upon framework to construct composite indicators, the idea of composite indices has been extensively used to assess vulnerability or resilience at national and regional levels (see Asadzadeh et al., 2017; Beccari, 2016; Spielman et al., 2020).

An exemplar of quantifying vulnerability is presented by Flanagan et al. (2018) who construct a composite index of social vulnerability. Those scholars integrate multiple socioeconomic and demographic factors that influence the resilience of communities, operationalized via four domains of census variables: (1) socioeconomic status (inclusive of income, poverty, employment, and education), (2) household composition (capturing age [< 18 or > 65 years], single parent-household, and disabilities), (3) minority status and language \(comprising race, ethnicity, and English language proficiency), and (4) housing and transportation (reflecting focal housing structures [mobile homes] and vehicle access) (Flanagan et al., 2018; Spielman et al., 2020) (see Fig. 1).Footnote 5 Together, we propose that these factors provide an understanding of the depth and breadth of one’s social vulnerability, and we believe such an approach to be necessary for organizations to more fully understand and address consumers’ lived vulnerability experiences.

Considering such a portfolio of indicators (Fig. 1) allows us to conceptualize a consumer’s breadth and depth of vulnerability. The breadth of vulnerability refers to the number of (sub-)indicators (e.g., akin to a [0/1] count) that apply to a focal consumer. With depth of vulnerability, we refer to the degree of impact, for example, the deviation of a consumer’s income from the poverty level.Footnote 6 Such (sub-)indicators of breadth and depth can then be aggregated and compared, for example, to an organization’s customer population. As such, the two dimensions of breadth and depth provide initial insights into different vulnerability states. Accordingly, we propose that managers—similar to policymakers and disaster managers for whom such social vulnerability indices are typically intended—can benefit from analogous indices to better understand their customers’ vulnerability breadth and depth.

Note that our perspective to assessing vulnerability experiences is akin to established approaches for risk-based pricing. Some sectors estimate consumer vulnerability to certain risks (e.g., the risk to default for consumer loan settings, or the likelihood of having a car accident in insurance settings), which then is reflected in risk-based pricing. As such, some organizations already have experience and expertise in quantifying consumer vulnerabilities, at least from the risk-based pricing perspective. A related marketplace novelty is FICO’s “Resilience Index,” which is designed to more precisely predict borrower’s resilience to economic disruptions (https://www.fico.com/en/products/fico-resilience-index). This index “uses credit bureau information from both before and after the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009 to measure a person’s likelihood of paying the bills on time, even during times of financial uncertainty” (Frankel, 2020), and then rank-orders consumers by their sensitivity to a future economic downturn. Notably, although this composite index could be a helpful tool to protect consumers from vulnerabilities and bolster their resilience, its validity and reliability are relatively untested. Even more importantly, FICO designed this index for organizational risk management; as such, care must be taken so that such resilience scores are not inadvertently utilized in a way that can harm consumers who experience vulnerabilities. Instead, an organization’s expertise in assessing and predicting threats should be leveraged to proactively offer these consumers tailored services that mitigate their vulnerability and promote their resilience.

Vulnerability pathways as the links between vulnerability states

Pathways connect vulnerability states

The idea of breadth and depth of vulnerability circumscribes a two-dimensional perspective that provides an opportunity for marketing scholars and managers to map distinct vulnerability pathways. On a conceptual level, consumers can experience an increase or a decrease of the (i) breadth of their vulnerability, (ii) depth of their vulnerability, (iii) breadth and depth at the same time, or (iv) counter-directional pathways where breadth and depth change in different directions (i.e., one increases while the other decreases), as Fig. 2 illustrates. As such, our framework takes a long-range view of vulnerability recognizing that states are temporal and that there is movement between them. More specifically, we codify vulnerability state A as one where vulnerability impacts a few dimensions of the lived experience (breadth) and that those impacts are less invasive (depth). In vulnerability state B, there are few dimensions impacted (breadth) yet the impacts are more significant (depth). Vulnerability state C is where more aspects of the lived experience are impacted (breadth), though less significantly (depth). And vulnerability D is when many dimensions of the lived experience (breadth) are significantly impacted (depth). It is important to note that the manifestations of each vulnerability state will vary by individual as well as their social and geographic circumstances.

This framework highlights that vulnerability is not merely a state, but that a person’s current vulnerability evolves from vulnerabilities they previously experienced. While understanding vulnerability states (indicated as A, B, C, and D in Fig. 2) is important, focusing only on a single state overlooks critical insights as to how consumers “arrive” or “depart” from it. This can result in “blind spots” and an insufficient understanding of these consumers. For example, in a static view, a financial service firm could perceive two customers—who both experience vulnerability “state C”—as similar. Yet, a dynamic view reveals that a customer can arrive in state C via different vulnerability pathways. More specifically, consumer 1 may have arrived in state C from state A due to a recent medical diagnosis (an increase in vulnerability breadth), whereas consumer 2 may have arrived in state C from state D after receiving a promotion at work that increased her income and reduced the gap between her income and the official poverty level income (a reduction in vulnerability depth).

Our dynamic lens captures increasing and decreasing levels of vulnerability. As such, it unearths interdependencies inclusive of temporal dimensions reflected in a consumer’s life course reflecting their history (accumulated experiences and resources at Tn-1), their current life circumstances (Tn), and the short- and long-term effects of behaviors on their future life course (Tn+1) (Bernardi et al., 2019). It is important to understand what causes these shifts to occur; therefore, building from LCT (Bernardi et al., 2019; Hutchison, 2019), we incorporate the concepts of turning points and path dependencies, which influence vulnerability pathways.

Turning points and path dependencies help explain vulnerability pathways

Turning points represent a “deviation or disruption in the trajectory an individual has been on or from one that was personally or socially expected in the future” (Bernardi et al., 2019, p. 4). At turning points, the life trajectory makes a distinct shift—upward or downward—which alters future opportunities and experiences in the short- and, potentially, long-term. Notably, the idea of turning points is related to inflection points, which Salisbury et al., (2023 p. 659) define as points when a consumer’s financial vulnerability “shifts significantly due to changing circumstances, life events, or consumer choices.” We employ the term “turning points”, which encompasses a broad range of disruptions, inclusive of financial, to explain vulnerability pathways.

Research on LCT found that turning points change how people perceive and understand their life (e.g., perceptions of (in)stability and (un)certainty), and can transform an individual’s self-concept, beliefs, or expectations; as such, turning points represent a shift in “how a person views the self in relation to the world and/or a transformation in how the person responds to risk and opportunity” (Hutchison, 2019, p. 354–5). Turning points can result from conscious decisions, for example, when an individual starts their own household, gets married, changes careers, or adopts a healthier lifestyle. However, turning points can also be the result of external shocks, such as becoming unemployed, getting a divorce, or being in an accident. Turning points may have differential impacts on vulnerability when encountered during distinct risk periods, which include, among others, young adulthood, retirement, unemployment, lone parenthood, or health impairments (Vandecasteele et al., 2021).

Path dependencies account for “the relevance of the past, not just the recent past but also the far-away past, in determining the present;” accordingly, some scholars describe this reality as “shadows of the past” (Bernardi et al., 2019, p. 3) On a conceptual level, path dependencies are related to the trajectories that Blocker et al. (2023, p. 496) define as a “continuous path of aggregate and fluctuating resources relative to overall resource sufficiency (consumption adequacy) over time.” Path dependencies provide an understanding of vulnerability dynamics because “early life privileges or hardships can pile up and be compounded over time” (Bernardi et al., 2019, p. 3); therefore, vulnerabilities at any point in time are the result of the accumulation of (dis-)advantages over time. In other words, path dependencies capture the fact that the probability that a vulnerability-shifting event occurs and the direction of a change in a consumer’s vulnerability at time T depends on her longer life history. This also means that the universe of future pathways is influenced by the consumer’s history and that the corresponding degrees of freedom might be limited or restricted as a function of the causal impact of previous experiences, events, and decisions in life (Bernardi et al., 2019; Spini et al., 2017).

Taken together, drawing on the idea of turning points and path dependencies and following prior work on vulnerability, we propose a framework that goes beyond vulnerability states (A, B, C, D in Fig. 3) to indicate the importance of vulnerability pathways that connect these states as identified by the arrows in Fig. 3 (vulnerability-increasing pathways: 1.1.-1.5; vulnerability-decreasing pathways: 2.1–2.5).

Our focus on vulnerability dynamics also unearths insights into the mechanisms underlying up- and downward pathways (i.e., consumers moving from a nonvulnerable state into a vulnerable state, and vice versa). By mapping the portfolio of vulnerability pathways, we reveal the threat of distinct vulnerability-increasing paths (Fig. 3, left panel) and the opportunities of distinct vulnerability-decreasing paths (Fig. 3, right panel) that influence the trajectory of vulnerability pathways. To illustrate, as the experience of becoming more vulnerable (e.g., paths 1.1 or 1.2) is stressful and threatening, it is likely that consumers must invest more (e.g., financial, physical, psychological) resources to navigate this threat. Once an initial increase in vulnerability occurs, consumers may consequently become even more vulnerable due to the ongoing diminishment of their resources in a process “by which initial loss begets further loss” when those with fewer resources are vulnerable to resource loss and lack the resources to offset the losses previously incurred (Hobfoll, 2001; Lin & Bai, 2022, p. 726). The consequence can be a self-perpetuating and damaging cycle of escalating vulnerability because of a downward spiral. Such spirals of consumer vulnerabilities can also result from spillover effects: Spillover effects reflect the interdependences between life domains where the individuals’ goals, resources, or behaviors in one domain (e.g., work or residence) are connected to goals, resources, or behaviors in other domains (e.g., education or leisure) (Bernardi et al., 2019). To illustrate negative spillovers, consider a consumer losing her job. Such a loss can trigger not only financial vulnerabilities but also mental health or marital challenges.

In contrast, vulnerability-decreasing paths (e.g., paths 2.3 or 2.4) arise because individuals who become less vulnerable (i.e., gain more resources) become more capable and access greater resources. Thus, initial decreases in vulnerability (and the corresponding resource gain) beget future gains, thus generating positive, self-perpetuating upward spirals (Burns et al., 2008). This can elicit positive spillover effects. Consider how a change in employment might not only increase financial resources but also contribute to physical/psychological well-being. These spillover effects—negative or positive—occur because actions and circumstances in one domain are interconnected with other domains of a consumer’s life (Spini et al., 2017).

Taken together, these considerations illustrate that consumers in state B may have distinct vulnerability pathways, which shape their needs, preferences, and desires in the marketplace, which in turn may impact the organizations they interact with and how they (can or desire to) interact with those organizations. We expect that organizations can serve customers better and more benevolently when they understand these vulnerability pathways and the opportunities and threats related to vulnerability-increasing and vulnerability-decreasing pathways. Therefore, consistent with recent work (Blocker et al., 2023; Hill & Sharma, 2020; Salisbury et al., 2023), we propose a more deliberate and proactive focus on vulnerability dynamism in marketing. Next, derived from our dynamic perspective, we offer suggestions on how firms might partner with consumers to co-create tools and strategies that reduce consumer vulnerabilities and help consumers build resilience.

Reducing vulnerability and increasing resilience: A consumer agency lens

Resilience refers to a person’s “reduced vulnerability to environmental risk experiences, the overcoming of stress or adversity, or a relatively good outcome despite risk experiences” (Rutter, 2012, p. 336). It is important to recognize that there are a variety of factors which contribute to an individual’s resilience; for example, social support, sense of belonging, self-regulation, problem-solving, hope, motivation to adapt, purpose, positive views of self, and positive habits. Interventions that leverage these factors can help increase resilience. For example, “interventions based on a combination of cognitive behavioural [sic.] therapy and mindfulness techniques” are effective in promoting individual resilience (Joyce et al., 2018, p. 1, see Liu et al., 2020 for additional findings from a meta-analysis). These factors can serve as an initial inspiration for organizational efforts to promote consumer resilience, as Table 2 illustrates in the contexts of financial services and healthcare. In parallel, it could be even more beneficial for organizations to design a comprehensive and systematic approach to proactively support consumers in building resilience. In the next section, we merge insights from research on resilience as a dynamic concept with disaster research to derive a systematic approach that can guide organizations in co-creating distinct types of consumer agency that fuel resilience.

Building resilience-fueling consumer agency

Aligned with the emerging focus on vulnerability dynamics in marketing (Blocker et al., 2023; Hill & Sharma, 2020; Salisbury et al., 2023), research in psychology has underscored the dynamic nature of resilience (e.g., Masten et al., 2021). In fact, scholars are increasingly suggesting that resilience should “be viewed as a process and not as a fixed attribute of an individual” (Rutter, 2012, p. 335). This process-based view implies that resilience can be developed, which is consistent with the emphasis that life course theory (LCT) puts on an individual’s agency for adaptation and change (Bernardi et al., 2019; Elder, 1995). LCT underscores the role of human agency—defined as the use of personal power, volition, and capability to achieve one’s goals—to account for the reality that people can take independent action (e.g., setting goals, planning a course of action, and persisting despite distractions and obstacles) to cope with stressors, threats, and difficulties they experience over the course of their lives (Hutchison, 2018, p. 2147; see also Bandura, 2006). Against this background, we suggest that organizations help consumers build such personal agency, and thus increase consumer resilience. Specifically, grounded in research on community resilience to (natural or man-made) disasters, we propose that organizations can adopt a systematic approach to supporting consumer resilience by co-creating five types of resilience-fueling consumer agency: the agency to (1) anticipate, (2) prevent, (3) prepare, (4) adapt, and (5) transform (Manyena et al., 2019; Paton & Buergelt, 2019; Vázquez-González et al., 2021).

Resilience via consumer agency to anticipate, prepare, and prevent

The first three types of resilience-fueling agency occur in “vulnerability state A.” This state, where vulnerability is low, is an opportunity for organizations to collaborate with consumers and focus on anticipation, preparedness, and prevention in recognition of potential crises (Manyena et al., 2019; Vázquez-González et al., 2021). This collaboration is essential to ensure that organizations’ view of vulnerability is consistent with those they serve (e.g., consumers’ perception and understanding of their own vulnerability). Through open dialogue and collaboration, organizations may better understand consumers’ lived experiences and gain a more accurate and holistic view of the vulnerabilities they can help prevent or mitigate.

Research on disasters underscores the need to anticipate future threats as crucial for proactive crisis management (Van Niekerk & Terblanché-Greeff, 2017). As such, organizations should help consumers to identify, understand, and anticipate their vulnerabilities via early-detection “horizon scanning” systems. Such anticipatory systems should include extrapolated vulnerability scenarios so that crises are not only anticipated but prevented (akin to medical screening for preexisting conditions; Manyena et al., 2019). In summary, a key objective for consumers and organizations is to collaborate to put in place a portfolio of measures that prevent damage or mitigate root causes of consumer vulnerabilities. We briefly illustrate how marketers might co-create these types of consumer agency.

Illustrations of building consumer agency to anticipate, prepare, and prevent

As a starting point for anticipation, preparation, and prevention, organizations and consumers need to account for spillover effects—the reality that events and actions in one domain of a consumer’s life can affect gains and losses in other domains (Spini et al., 2017). Thus, organizations should be attentive to vulnerabilities related to customers’ life transitions (e.g., parenting, marital, or employment status) and anticipate that vulnerabilities emerge related to unpredictable (turning point) events (e.g., accidents, job loss). In anticipation of such events, organizations can design tailored service solutions that mitigate vulnerabilities and reduce the risk that consumers slip into spirals of increasing vulnerabilities. In parallel, organizations can leverage evolving technologies to provide early warning systems that include proactive real-time and context-specific information about consumer vulnerabilities (e.g., real-time financial risk exposure, account balances, and credit scores at the time of purchase) or health-related vulnerabilities (e.g., real-time bio-/medical indicators through wearables or implants) that empower consumers to take actions that prevent risks.

Moreover, creating resilience is linked to the idea that knowledge fuels the empowerment of people experiencing vulnerability. For example, banks may anticipate that homeowners with variable mortgage rates are at risk if interest rates increase. To prepare consumers, a bank may need to educate customers on the risks of variable-interest mortgages and encourage those consumers to shift to fixed-rate mortgages. This education helps prevent customers from defaulting on their mortgage payments. Broadening the anticipatory and preparatory lens, some banks—when a customer takes out a loan for a car—might offer an educational program regarding how to maintain the vehicle with regular service. Such a program supports customers in maintaining their vehicle in good condition throughout the length of the loan product and retaining some value for resale.

Importantly, all efforts to promote customer education ought to be deliberately designed to build the agency to anticipate, prepare for, and prevent vulnerabilities. While organizations often host literacy events or product information sessions, it is important for organizations to recognize the unique needs of their various customers and, especially, provide tailored tools to empower customers experiencing vulnerability. For instance, there is a plethora of generic financial information available in the marketplace, and (especially) consumers with vulnerabilities might be easily overwhelmed by the amount and complexity of this information. When a consumer lacks the knowledge required to understand financial markets and services, it can be difficult for them to ask questions as they may be embarrassed by their lack of knowledge or simply not have the language or understanding necessary to formulate relevant questions. In the spirit of marketplace inclusion, effective information for the most vulnerable groups should be presented in language that is easy to understand, made available through interfaces and channels that consumers experiencing vulnerability are likely and able to access, must be relevant to the consumer’s most pressing and common challenges in light of their pathways, and be trustworthy and guided by empathy so that it has consumers’ best interests at heart (Arashiro, 2011). Following these principles helps firms to empower customers with vulnerabilities via the agency to anticipate, prepare, and prevent.

Resilience via the consumer agency to adapt and transform

The remaining two types of resilience-fueling agency occur outside of “vulnerability state A.” In other words, an event has occurred which has made a consumer more vulnerable; at this time, consumers must display adaptive agency or transformative agency to absorb and overcome the impact of the crisis (Vázquez-González et al., 2021).

Adaptive agency means consumers adjust in response to a crisis (e.g., change aspects of their professional or personal lives) to absorb the damage. At this point, response plans (that have been designed as part of the above preparation efforts) are activated, for example, ‘risk transfer mechanisms’ such as insurances. A related component of adaptive agency is the consumer’s recovery time, which represents the time it takes a consumer to restore their basic functioning in their (personal/professional) life to the levels from before the crisis (Vázquez-González et al., 2021). Thus, the earlier stage of “preparing” resilience needs to include a focus on (a short) recovery time. In the disaster research literature, adaptation has also been characterized as “bouncing back” to the original (pre-crisis) state. That is, adaptation tends to support the maintenance of the status quo, which could have contributed to (or even caused) the crisis in the first place (Manyena et al., 2019). Thus, although anticipation, prevention, and preparation are beneficial, they might “simply” maintain the pre-crisis status quo. Consumers might “bounce back,” but they do not learn from the crisis and might remain vulnerable to its underlying causes. This important insight points toward the benefits of the agency to transform.

Transformative agency indicates that consumers “bounce forward” by learning from and pursuing new opportunities related to the crisis. In other words, crises are recognized as opportunities for consumers to acquire new knowledge about their behaviors (e.g., habits, practices, decision-making) as well as their environmental and social structures (Paton & Buergelt, 2019). Because transforming highlights the importance of removing structural elements that make consumers vulnerable, the metaphor of “bouncing-forward” points to interventions that address the root causes of a consumer’s vulnerability post-crisis (Sudmeier-Rieux, 2014).

Illustrations of building consumer agency to adapt and transform

Because vulnerabilities can occur and escalate quickly, organizations ought to structure flexibility into their offerings so that they can be swiftly tailored for consumers experiencing vulnerability at the time of crises. For example, consumers who experience an increase in vulnerability might quickly have difficulty paying for essential services (e.g., transportation, electricity, telecommunications). Yet, organizations can alter the default design of their offerings to buffer consumers against short-term or long-term vulnerabilities. Some financial service firms have such programs in place: consider Wells Fargo AssistSM, which can help customers with challenges related to credit card and loan payments (https://www.wellsfargo.com/financial-assistance/). Still a step further goes the idea that organizations can assist consumers in adapting or transforming by providing assistive services. For example, financial service firms might assist customers when a medical emergency triggers vulnerabilities such that various healthcare providers become part of a consumer’s vulnerability pathway. As one marketplace example, note that Discover Bank has partnered with an organization called SpringFour to connect customers who experience financial hardships (e.g., from medical issues, disabilities, serious accidents, and unemployment or income changes) with “local resources to save money on things like groceries, utility costs, and prescription medications” (https://springfourdirect.com/discover/). In doing so, organizations expand partnering opportunities with their consumers and other organizations, which has the potential to result in benefits for consumers and the organizations involved.

Future research directions and opportunities

Increasing inclusivity within marketplaces requires organizations to (co-)create more tailored services that allow (more) diverse types of consumers to interact with and access the organization’s offerings. In order to become more inclusive, marketing research can “benefit from adopting a more dynamic view of consumer vulnerability” (Hill & Sharma, 2020, p. 552). Against this background, our work offers multiple opportunities for future research (see Table 3) to help make this perspective become part of marketplace reality. Prior empirical work on consumer vulnerability tends to investigate only parts of highly complex and nonlinear vulnerability dynamics that are driven by the interplay of life domains, levels, and time (for an exception, see Salisbury et al., 2023). Such approaches largely miss the opportunity to explain the distinct pathways identified in Fig. 3.

Our development of a dynamic view of consumer vulnerability provides organizations with an opportunity to assess and refine their internal capabilities to proactively support consumers with vulnerabilities. By understanding how vulnerability states may emerge and transform in the lived experience of consumers, organizations can better engage in transparent and open dialogue with consumers. Notably, consumers are not solely responsible for navigating vulnerabilities, but rather firms and consumers should navigate these situations together by co-creating effective strategies for consumers. Understanding vulnerability states and pathways allows marketers to proactively create processes in support of consumers with vulnerabilities. With that understanding, organizations can more effectively support consumers as they navigate those vulnerabilities, and ideally identify opportunities to mitigate experiences of vulnerability. Our approach supports, but also extends, Alkire et al.’s (2023) view of responsibilities of organizations to improve the well-being of its stakeholders with a dedicated focus on consumers experiencing vulnerability, who often remain overlooked.

Conceptual foundations: Novel types of consumer vulnerabilities

In their insightful research, Salisbury et al. (2023) underscored that, to understand vulnerability dynamics, it is important to consider the types of access to financial resources consumers have (e.g., via personal funds, financial services, social bonds, governmental programs) and the types of harm they may have experienced (e.g., economic, consumption, health, social). These ideas are aligned with and can be platforms to extending our idea of distinct pathways. Specifically, we encourage more research on typologies / taxonomies of vulnerabilities. For example, in the financial realm, Chipunza and Fanta (2023, p. 784) distinguish three dimensions of vulnerability as the “inability to accumulate savings after meeting basic living costs (saving vulnerability), the inability to attend outdoor recreational activities (lifestyle vulnerability), and the inability to meet rudimentary living costs (expenditure vulnerability).” Empirical marketing research could explore how such types relate to corresponding consumer responses and our pathways. Recalling the recent FICO Resilience Index, we believe there are opportunities to identify industry-specific vulnerability indicators to help managers better understand the breadth and depth of vulnerabilities their customers may experience (e.g., types could emerge as a function of distinct breadth-x-depth configurations).

Conceptual foundations: New constructs

Our framework aims to inspire marketing scholars to identify, describe, and explain the different pathways and their distinct psychological mechanisms and behaviors in more detail. For example, more work is needed on the role of heterogeneity with respect to the unique vulnerability pathways different individuals experience in life. This provides the opportunity to go beyond marketing constructs that have received the majority of scholarly and managerial attention (e.g., customer satisfaction and loyalty) to include new constructs that are more closely related to experiences of vulnerability (e.g., consumer-perceived dis-/respect, dignity, hope/-lessness). Consider, for example, that economists suspect that despair induced by financial stressors helps explain increases in suicides and drug/alcohol abuse (Shanahan et al., 2019). Marketing research can examine whether certain paths in our vulnerability framework influence such life-threatening behaviors and, on a more positive note, how marketing interventions might help prevent them. Moreover, we note that not all stress experiences are negative (i.e., distress); rather, some stressful episodes, called eustress experiences, can be associated with positive feelings and well-being outcomes (Selye, 1973). Thus, appraising a vulnerability as a challenge could elicit eustress and activate consumers to overcome this challenge (e.g., Mende et al., 2017). These distinct stress constructs might shed light onto the dynamic mechanisms that fuel increasing and decreasing vulnerability paths.

Dynamics of spillover effects

Future empirical research should examine spillover effects and how such spillovers may impact consumers along vulnerability-decreasing or -increasing pathways. For example, marketing scholars can examine whether (and in which forms) spillover effects occur (e.g., complementary, competing, and compensatory spillovers or spillovers from a person’s professional realm into the personal realm or vice versa) or whether distinct spillovers result related to turning points versus path dependencies. Such research could, for example, be linked to prior work on compensatory consumption behaviors (e.g., Mandel et al., 2017). Relatedly, marketers might examine to what extent consumers can anticipate and prevent such spillover effects and how organizations can help consumers understand complementary, competing, and compensatory spillover effects that might occur across domains (e.g., finances and health).

Dynamics of “shadows of the past and the future”

Consistent with calls for more marketing research that incorporates longitudinal perspectives (e.g., Chintagunta & Labroo, 2020), we encourage marketers to study distinct trajectories (“shadows of the past,” Bernardi et al., 2019) and their impact on current decisions. Researchers can also examine consumer anticipation (i.e., “shadows of the future”) and forward-looking decisions and related concepts (e.g., hope, optimism). To explore such questions, marketers can draw on life-course research that conducted large-scale panel studies, which become increasingly feasible and preeminent in social sciences. Such studies could employ event history methodology or conduct multilevel, multidimensional longitudinal analysis (e.g., latent growth-curve modeling and sequence analysis to analyze multidimensional life course trajectories; Bernardi et al., 2019). Relatedly, our framework raises the question of which novel methods and data (e.g., composite indicators) can capture and model the complexity of vulnerability pathways best (i.e., over time and across multiple domains of consumers’ lives).

Dynamics of duration and timing of vulnerability experiences

To extend prior work on the effects of distinct time-related types of vulnerability experience (e.g., chronic vs. transient; Blocker et al., 2023), marketing research could investigate the effects of (a) the duration of vulnerability experiences, as well as (b) the life stage in which these experiences occurred (e.g., Mende et al., 2023 for a discussion of these aspects in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic). For example, with respect to the duration of the vulnerability experience, LCT suggests that longer durations tend to result in more enduring psychological / physical consequences for an individual (et vice versa). In terms of the life stage, LCT proposes that the effects of vulnerability likely depend on life stages that are particularly sensitive to certain types of effects, such as the elderly and young (Settersten et al., 2020). Thus, additional research is warranted to better understand the impact of life stages on vulnerability experiences.

Dynamics of consumer resilience

Marketing research needs to examine how marketers can develop and maintain consumers’ agency to anticipate, prepare, prevent, adapt, and transform. We need empirical insights into when and why which type of agency matters more (or less) and how intended, positive (or unintended) effects of these types of agency manifest. For example, under which circumstances might consumers choose (not) to invest in building resilience-fueling agency? Beyond our specific conceptual focus on consumer agency, marketing research needs to identify more predictive measures and indicators of consumer vulnerabilities (beyond extant measures like credit scores and risk aversion trait differences). Another perspective can draw on the resilience literature in psychology, which suggests that experiences of “adversities may either increase vulnerabilities through a sensitization effect or decrease vulnerabilities through a steeling effect” (Rutter, 2012, p. 337, emphasis ours). Marketing research can help examine when such sensitization or steeling effects emerge and which mechanisms help explain them.

Interdisciplinary inspirations: Multi-level perspectives

In their inspiring work on poverty, Blocker et al. (2023, p. 490) call for marketing research to build on sociological perspectives to develop new questions at interdisciplinary intersections to enhance marketing’s theoretical reach. Directly responding to this call, we draw on life course theory in sociology (e.g., Bernardi et al., 2019; Elder, 1995) to identify a novel portfolio of vulnerability-increasing and vulnerability-decreasing pathways. Yet, our multidimensional framework can be extended via a multilevel perspective to further capture the reality that consumers are linked with the life courses of others, as well as social networks and the broader external social, historical, and economic contexts (Bernardi et al., 2019; Elder, 1995). Such multi-level perspectives focus on “interactions between individual (e.g., personality traits, self-regulations, coping strategies, information processing), group (e.g., groups and networks, intergroup relations), and collective (e.g., institutional and cultural processes, descriptive and prospective norms) levels” to better observe, describe, and explain their relevance in influencing (nested) vulnerabilities and consumers’ experiences and behaviors (Spini et al., 2017, p. 14; also Bernardi et al., 2019; Macioce, 2022). Another stream of research could extend our focus to study how the aforementioned types of consumer agency can be built on a household- or community-level. To do that, marketers can draw on literature on resilience at the supra-individual level (e.g., on community resilience, see Berkes & Ross, 2013, Barrett et al., 2021; Mochizuki et al., 2018; for a theory of group vulnerability, see Macioce, 2022).

Interdisciplinary inspirations: Novel theories

While we drew from disaster research and life course theory in sociology, other theoretical backdrops can further enrich marketing research on vulnerability. For example, grounded in legal philosophy, Fineman (2008, 2013, 2017) conceptualizes vulnerability as universal, inherent in the human condition for every individual, and constant throughout a person’s life, although she recognizes that the specific circumstances affecting vulnerability can change. Against this background, Fineman identifies the importance of embodied and embedded differences related to vulnerability: embodied differences evolve within each individual body (the progressive biological and developmental stages within an individual life) and include physical variations (e.g., age, physical and mental ability, other bodily differences). In parallel, embedded differences emerge as a function of networks of economic, social, cultural, and institutional relationships (e.g., in educational, employment, financial, and other institutions). This perspective leads Fineman (2013) to propose thought-provoking ideas that marketing research can draw on, for example, that those who obtain power and wealth are seen as having done so purely on their own, which, in turn, undermines a sense of social solidarity and diminishes sympathy and empathy for those in need.

From the field of bioethics, Luna (2009, 2019) proposes a deliberately more fluent perspective and argues that there are different vulnerabilities resulting from distinct though potentially overlapping layers of vulnerability; some of them may emerge due to a person’s social circumstances or reflect relations between the person (or a group of persons) and their situational circumstances or context. Broadly, the theory argues that these different layers may be contextually acquired or removed one by one. This view results in cascades of potential vulnerabilities and emphasizes that a particular situation can render someone vulnerable; yet, if the situation changes, the person may no longer be considered vulnerable. The idea of layers provides more flexibility to the concept of vulnerability and makes it a deliberately contextual and relational one; it also suggests that marketers ought to focus on minimizing and eradicating layers of vulnerability. Appendix A Table 4 provides some further details in comparing key characteristics of the universalist theory and layered theory to inspire marketing research.

Organizational proactivity: Linking service development and innovation to consumers’ lived vulnerability experiences

Our work is aligned with recent research suggesting that understanding consumer (financial) vulnerabilities can and should be directly linked to marketing strategy, for example, a company’s product portfolio management (Salisbury et al., 2023). Closely related to this insight, our discussion suggests that organizations should systematically develop services to address consumer hardship. Specifically, our framework points to the need and opportunities for organizations to develop dedicated vulnerability-focused service solutions. To provide fitting solutions for vulnerable customers, organizations need to proactively develop vulnerability-related innovation capabilities. Notably, not all organizations possess these capabilities. For example, organizations in developed countries (deliberately or unwittingly) frequently do not focus on serving the needs of consumers in the context of their distinct vulnerability profiles. This reality not only undermines consumer well-being but also results in organizations missing opportunities to serve markets of consumers who are experiencing vulnerability (e.g., underbanked consumers, see Mende et al., 2020). To develop such capabilities, and especially to identify the needs of people experiencing vulnerability, managers might draw on research on other “overlooked” segments, such as customers at the Base-of-the-Pyramid (BoP) (Prahalad, 2012). Management concepts such as inclusive innovation, grassroots innovation, and social innovation, which develop new ideas that aspire to enhance social and economic well-being for people in society (Brem & Wolfram, 2014; George et al., 2012; Luiz et al., 2021) can all be fruitful inspirations for organizations. For example, Pansera and Sarkar (2016) find that innovations generated by a low-income population not only improve an organization’s ability to satisfy previously unmet and ignored consumer needs, but also enhance its productivity and sustainability. These ideas are well-established in the innovation literature. Ironically, those notions are typically thought of for consumers in developing countries but rarely considered to serve consumers experiencing vulnerability in developed countries. More marketing research is needed to study how organizations in developed markets can incorporate a focus on consumers with vulnerabilities in their service design and innovation processes.

Organizational proactivity: Better targeting segments of consumers with vulnerability

Another challenge that is related to not recognizing the needs of consumers with vulnerabilities is that organizations might not be able to identify and target corresponding consumer segments. Accordingly, more research is needed that can inform and improve organizational customer segmenting and targeting efforts (Salisbury et al., 2023). In this regard, managers should note that developing nations have utilized a variety of approaches to improve the socio-political inclusion of people with vulnerabilities (e.g., micro-financing, social security, and market-based solutions; Singh & Chudasama, 2020). One crucial finding from such poverty alleviation programs is the importance of targeted efforts. For example, to lift its more than 70 million rural impoverished people above the poverty line, the Chinese Government initiated a policy in 2014 that included targeted measures of accurate poverty identification (including the specific needs of people who are impoverished for distinct reasons such unemployment or diseases) and corresponding interventions to ensure that assistance reaches the poverty-stricken households and communities (e.g., by mobilizing support at the local municipal and county-level government); the objective of these targeted programs is to improve the accuracy and effectiveness of poverty alleviation efforts (Chong et al., 2022).

Such governmental programs can inform and inspire organizations so that marketers can more accurately identify the needs of consumers experiencing vulnerability and develop solutions.Footnote 7 For example, some programs in China emphasize the importance of local knowledge―specifically, the interplay of know-who and know-how―for identifying households with the greatest needs, establishing relationships with them, and selecting fitting interventions. Indeed, Cai et al. (2022) observe that “using people who are familiar with the poor household has become the key mechanism to solve the targeting problem.” This insight can help organizations in serving consumers experiencing vulnerability in developed countries. For example, financial service firms could leverage their branches to embed “resilience managers,” as champions for consumers who are experiencing vulnerabilities in their local market. Such localized initiatives can help improve inclusion in areas that are traditionally underserved. This intentionality in collaboration of firms with consumers can enrich the development of programs that aim to alleviate or prevent vulnerabilities by providing nuanced insights into how consumers perceive themselves and the world. Such nuanced insights on an individual level can be crucial as we acknowledge the relevance of consumer heterogeneity. For example, the motivation and capacity for consumers to move from one vulnerability state to another might be influenced by individual-level and/or cultural heterogeneity (e.g., political orientations, or cultural dimensions such as Hofstede, 2016). To illustrate, consumers with more collectivist (vs. individualistic) cultural orientation might be more likely to welcome organizational efforts to co-create vulnerability mitigation strategies. Similarly, Hofstede’s dimension of “motivation towards achievement and success” (formerly called “masculinity vs. femininity”) might be relevant because it refers to the societal preference for achievement, assertiveness, and material rewards for success; thus, consumers with a relatively more “feminine” (vs. “masculine”) orientation might be more welcoming vis-a-vis a company’s aim to co-create vulnerability mitigation strategies with them.

Relatedly, it is equally important for managers to note the reality that consumers may have different visions of themselves and their level of vulnerability; that is, two consumers who are objectively equally vulnerable (per quantifiable vulnerability sub-/indicators) might (subjectively) perceive their vulnerability differently from each other, which can then affect how they interpret strategies designed to reduce vulnerabilities and the extent to which they are willing to collaborate with organizations to build consumer resilience. In short, organizations need to consider that consumers who experience different types of vulnerabilities are likely to be influenced by (sub-)cultural and geographical diversity; such heterogeneity can undermine their motivation to collaborate with organizations. However, we prescribe to an optimistic paradigm that proposes that by collaborating, consumers and organizations can co-create strategies that more appropriately meet the needs of consumers and effectively reduce their vulnerabilities.

Finally, related to our optimistic paradigm, we underscore that any organizational co-creation efforts to reduce consumer vulnerability should not be used to exploit consumers for profit or to undermine their freedom of choice via a “paternalistic” approach. That is, managers must act ethically when determining the breadth and depth of consumer vulnerability and when developing strategies to reduce vulnerabilities and build consumer resilience. Such an ethical approach to collaboration also helps ensures organizations promote multi-stakeholder efforts (Alkire et al., 2023) in reducing vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

This research expands the understanding of consumers’ lived vulnerability experiences by focusing on the dynamic aspects of vulnerability. Understanding shifts in the breadth and depth of a consumer’s vulnerability, as well as how that consumer arrived in that state of vulnerability, is critical from a marketplace inclusion perspective as it helps marketers reduce consumer vulnerabilities and enhance consumer resilience. Although such a perspective might not be intuitive (e.g., from a pure shareholder perspective), we notice that novel business approaches are emerging that seem to be consistent with our rationale. Consider the emergence of “ethical banking,” which includes a set of banking practices that aim to counteract problems such as social inequality, gender discrimination, as well as climate change, and environmental sustainability (Valls Martínez et al., 2021 for a detailed analysis). In contrast to conventional banks—which typically aim to maximize their profit—ethical banks follow a threefold principle in their operations, namely the balance of profit, people, and planet; consequently, the foundational premise of ethical banking is to position the client as the center of a banking business that is driven by social mentalities and active solidarity (Valls Martínez et al., 2021).

The emergence of ethical banking can serve as inspiration for other industries to consider consumer vulnerabilities as related to their core business (model). Against this background, we hope our research offers an enhanced understanding of lived vulnerability experiences as we extend existing research of consumer vulnerability dynamics (Blocker et al., 2023; Hill & Sharma, 2020; Salisbury et al., 2023) to introduce an expanded framework that brings in tenants from other disciplines. We hope that our framework encourages marketing research on how organizations can better assess vulnerability states and pathways to ultimately reduce consumer vulnerabilities and promote consumer resilience.

Notes

This emphasis on inclusiveness emerges from the paradigm of Transformative Consumer Research (Anderson et al., 2013; Mick 2006), and it is consistent with efforts by leading outlets such as JMR’s ‘Mitigation in Marketing’ and JM’s ‘Better Marketing for a Better World’ initiatives, as well as the Responsible Research for Business and Management (RRBM) initiative (Mende and Scott 2021).

This paper utilizes the terms “consumer vulnerability” and “vulnerable consumer” when referring to previous research on the topic as used and defined by those sources. However, recognizing that a strength-based approach can help avoid further stigmatizing or objectifying people experiencing vulnerability and acknowledging that a person-first language is important (e.g., Boenigk et al., 2021), other terms are used throughout this paper. We are grateful to one of the anonymous reviewers emphasizing the importance of these terminological aspects.

An individual’s demographic characteristics alone do not, per se, cause them to be more vulnerable; as such, we do not intend to promote the idea of ‘victim groups’ or ‘rescue groups’ (see: Flanagan et al., 2018).

Because there are dozens of composite indicator frameworks in disaster management research that were derived from 50 + methodologies, our goal is not to provide a systematic overview (e.g., see Asadzadeh et al., 2017; Beccari 2016), but simply to illustrate how companies might construct such indices (see Fig. 1).

The assemblance of such vulnerability data must go hand-in-hand with ethical principles and a comprehensive and systematic stakeholder (rather than shareholder) focus such that company actions are guided by the principles of mitigating consumers’ lived vulnerability experiences.

For example, a consumer is more vulnerable—ceteris paribus—when they rank at the 60% percentile rather than the 90% percentile of the amount that indicates the official poverty level in the U.S. Note that such indicators should be adjusted for regional or local income/cost-of-living and poverty levels (e.g., Nebraska vs. California).

We do not suggest that such programs can and should be simply copied without major adjustments to the open society and market-based systems in many Western countries; yet, they might inspire fresh thinking for marketers.

References

Aksoy, L., Alkire, N. N. L., Choi, S., Kim, P. B., & Zhang, L. (2019). Social innovation in service: a conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 30(3), 429–448.

Alkire, L., Russell-Bennett, R., Previte, J., & Fisk, R. P. (2023). Enabling a service thinking mindset: Practices for the global service ecosystem. Journal of Service Management, 34(3), 580–602.

Anderson, L., Ostrom, A. L., Corus, C., Fisk, R. P., Gallan, A. S., Giraldo, M., Mende, M., Mulder, M., Rayburn, S. W., Rosenbaum, M. S., Shirahada, K., & Williams, J. D. (2013). Transformative service research: An agenda for the future. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1203–1210.

Antonucci, T. C., Ajrouch, K. J., & Birditt, K. S. (2014). The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. The Gerontologist, 54(1), 82–92.

Arashiro, Zuleika (2011). Money matters in times of change: financial vulnerability through the life course. Retrieved March 6, 2023 from https://www.academia.edu/30497707/Money_matters_in_times_of_change_financial_vulnerability_through_the_life_course

Asadzadeh, A., Kötter, T., Salehi, P., & Birkmann, J. (2017). Operationalizing a concept: The systematic review of composite indicator building for measuring community disaster resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 25, 147–162.

Baker, S. M., Gentry, J. W., & Rittenburg, T. L. (2005). Building understanding of the domain of consumer vulnerability. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(2), 128–139.

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180.

Barrett, C. B., Ghezzi-Kopel, K., Hoddinott, J., Homami, N., Tennant, E., Upton, J., & Wu, T. (2021). A scoping review of the development resilience literature: Theory, methods and evidence. World Development, 146, 1–21.

Basu, R., Kumar, A., & Kumar, S. (2023). Twenty-five years of consumer vulnerability research: Critical insights and future directions. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 57(1), 673–695.

Beccari, B. (2016). A comparative analysis of disaster risk, vulnerability and resilience composite indicators. PLOS Currents Disasters, 8. https://currents.plos.org/disasters/author-faq/

Berkes, F., & Ross, H. (2013). Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Society & Natural Resources, 26(1), 5–20.

Bernardi, L., Huinink, J., & Settersten, R. A., Jr. (2019). The life course cube: A tool for studying lives. Advances in Life Course Research, 41, 100258.

Blocker, C., Zhang, J. Z., Hill, R. P., Roux, C., Corus, C., Hutton, M., & Minton, E. (2023). Rethinking scarcity and poverty: Building bridges for shared insight and impact. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 33(3), 489–509.

Boenigk, S., Kreimer, A. A., Becker, A., Alkire, L., Fisk, R. P., & Kabadayi, S. (2021). Transformative service initiatives: Enabling access and overcoming barriers for people experiencing vulnerability. Journal of Service Research, 24(4), 542–562.

Brem, A., & Wolfram, P. (2014). Research and development from the bottom up-introduction of terminologies for new product development in emerging markets. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 1–22.

Burns, A. B., Brown, J. S., Sachs-Ericsson, N., Plant, E. A., Curtis, J. T., Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. E. (2008). Upward spirals of positive emotion and coping: Replication, extension, and initial exploration of neurochemical substrates. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(2), 360–370.

Cai, C., Li, Y., & Tang, N. (2022). Politicalized empowered learning and complex policy implementation: Targeted poverty alleviation in China’s county governments. Social Policy & Administration, 56(5), 757–774.

Chintagunta, P., & Labroo, A. A. (2020). It’s about time: A call for more longitudinal consumer research insights. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 5(3), 240–247.

Chipunza, K. J., & Fanta, A. B. (2023). Quality financial inclusion and financial vulnerability. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(2), 784–800.

Chong, C., Cai, M., & Yue, X. (2022). Focus shift needed: From development-oriented to social security-based poverty alleviation in rural China. Economic and Political Studies, 10(1), 62–84.

Dunnett, S., Hamilton, K., & Piacentini, M. (2016). Consumer vulnerability: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(3–4), 207–210.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1995). The life course paradigm: Social change and individual development. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder, & K. Lüscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 101–139). American Psychological Association.

Ferraro, K. F., & Schafer, M. H. (2017). Visions of the life course: Risks, resources, and vulnerability. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 88–93.

Field, J. M., Fotheringham, D., Subramony, M., Gustafsson, A., Ostrom, A. L., Lemon, K. N., Huang, M.-H., & McColl-Kennedy, J. R. (2021). Service research priorities: Designing sustainable service ecosystems. Journal of Service Research, 24(4), 462–479.

Fineman, M. A. (2017). Vulnerability and inevitable inequality. Oslo Law Review, 4(3), 133–149.

Fineman, M. A. (2018). Vulnerability and social justice. Valparaiso University Law Review, 53, 341–369.

Fineman, M. A. (2008). The vulnerable subject: Anchoring equality in the human condition. Transcending the boundaries of law (pp. 177–191). Routledge-Cavendish.

Fineman M.A. (2013). ed. Vulnerability: reflections on a new ethical foundation for law and politics. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Fisk, R. P., Dean, A. M., Alkire, L., Joubert, A., Previte, J., Robertson, N., & Rosenbaum, M. S. (2018). Design for service inclusion: Creating inclusive service systems by 2050. Journal of Service Management, 29(5), 834–858.

Flanagan, B. E., Hallisey, E. J., Adams, E., & Lavery, A. (2018). Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index. Journal of Environmental Health, 80(10), 34.

Frankel, R. S. (2020) FICO introduces new resilience index. Here’s what it might mean for you. Forbes.com. https://www.forbes.com/advisor/credit-score/fico-resilience-index/. Accessed 11/02/2023.

George, G., McGahan, A. M., & Prabhu, J. (2012). Innovation for inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 49(4), 661–683.

Hanappi, D., Bernardi, L., & Spini, D. (2014). Vulnerability as a heuristic concept for interdisciplinary research: Assessing the thematic and methodological structure of empirical life course studies. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 6(1), 59–87.

Hill, R. P., & Sharma, E. (2020). Consumer vulnerability. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 30(3), 551–570.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421.

Hofstede, G. (2016). Masculinity at the national cultural level. In Wong, Y. J. & Wester, S. R. (Eds.), APA Handbook of Men and Masculinities, p. 173–186. American Psychological Association.

Hutchison, E. D. (2019). An update on the relevance of the life course perspective for social work. Families in Society, 100(4), 351–366.

Hutchison, E. D. (2018). Life course theory. In, R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Adolescence (2nd ed., pp. 2141–2150). Springer.

Joyce, S., Shand, F., Tighe, J., Laurent, S. J., Bryant, R. A., & Harvey, S. B. (2018). Road to resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. British Medical Journal Open, 8(6), e017858.

Lin, L., & Bai, Y. (2022). The dual spillover spiraling effects of family incivility on workplace interpersonal deviance: From the conservation of resources perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 184(3), 725–740.

Liu, J. J., Ein, N., Gervasio, J., Battaion, M., Reed, M., & Vickers, K. (2020). Comprehensive meta-analysis of resilience interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101919.

Luiz, O. R., Mariano, E. B., & Silva, H. M. R. D. (2021). Pro-poor innovations to promote instrumental freedoms: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 13(24), 13587.

Luna, F. (2009). Elucidating the concept of vulnerability: Layers not labels. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 2(1), 121–139.

Luna, F. (2019). Identifying and evaluating layers of vulnerability–a way forward. Developing World Bioethics, 19(2), 86–95.

Macioce, F. (2022). Towards a Theory of Group Vulnerability. The Politics of Vulnerable Groups: Implications for Philosophy, Law, and Political Theory (pp. 61–92). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Mandel, N., Rucker, D. D., Levav, J., & Galinsky, A. D. (2017). The compensatory consumer behavior model: How self-discrepancies drive consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(1), 133–146.

Manyena, B., Machingura, F., & O’Keefe, P. (2019). Disaster Resilience Integrated Framework for Transformation (DRIFT): A new approach to theorising and operationalising resilience. World Development, 123, 104587.

Masten, A. S., Lucke, C. M., Nelson, K. M., & Stallworthy, I. C. (2021). Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17, 521–549.

Mende, M., & Scott, M. L. (2021). May the force be with you: Expanding the scope for marketing research as a force for good in a sustainable world. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 40(2), 116–125.

Mende, M., Scott, M. L., Bitner, M. J., & Ostrom, A. L. (2017). Activating consumers for better service coproduction outcomes through eustress: The interplay of firm-assigned workload, service literacy, and organizational support. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 36(1), 137–155.

Mende, M., Salisbury, L. C., Nenkov, G. Y., & Scott, M. L. (2020). Improving financial inclusion through communal financial orientation: How financial service providers can better engage consumers in banking deserts. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 30(2), 379–391.

Mende, M., Grewal, D., Guha, A., Ailawadi, K., Roggeveen, A., Scott, M. L., Rindfleisch, A., Pauwels, K., & Kahn, B. (2023). Exploring Consumer Responses to COVID-19: Meaning Making, Cohort Effects, and Consumer Rebound. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 8(2), 220–234.

Mick, D. G. (2006). Meaning and mattering through transformative consumer research. Advances in Consumer Research, 33(1), 1–4.

Mochizuki, J., Keating, A., Liu, W., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., & Mechler, R. (2018). An overdue alignment of risk and resilience? A conceptual contribution to community resilience. Disasters, 42(2), 361–391.

Van Niekerk, D., & Terblanché-Greeff, A. (2017). Anticipatory disaster risk reduction. Handbook of Anticipation, 1–23. Springer International Publishing.

Pansera, M., & Sarkar, S. (2016). Crafting sustainable development solutions: Frugal innovations of grassroots entrepreneurs. Sustainability, 8(1), 51.

Paton, D., & Buergelt, P. (2019). Risk, transformation and adaptation: Ideas for reframing approaches to disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2594.

Prahalad, C. K. (2012). Bottom of the pyramid as a source of breakthrough innovations. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 29(1), 6–12.

Riedel, A., Messenger, D., Fleischman, D., & Mulcahy, R. (2022). Consumers experiencing vulnerability: A state of play in the literature. Journal of Services Marketing, 36(2), 110–128.

Rutter, M. (2012). Resilience as a dynamic concept. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 335–344.

Salisbury, L. C., Nenkov, G. Y., Blanchard, S. J., Hill, R. P., Brown, A. L., & Martin, K. D. (2023). Beyond income: Dynamic consumer financial vulnerability. Journal of Marketing, 87(5), 657–678.

Selye, H. (1973). The Evolution of the Stress Concept: The originator of the concept traces its development from the discovery in 1936 of the alarm reaction to modern therapeutic applications of syntoxic and catatoxic hormones. American Scientist, 61(6), 692–699.

Settersten, R. A., Jr., Bernardi, L., Härkönen, J., Antonucci, T. C., Dykstra, P. A., Heckhausen, J., Kuh, D., Mayer, K. U., Moen, P., Mortimer, J. T., Mulder, C. H., Smeeding, T. M., van der Lippe, T., Hagestad, G. O., Kohli, M., Levy, R., Schoon, I., & Thomson, E. (2020). Understanding the effects of Covid-19 through a life course lens. Advances in Life Course Research, 45, 100360.

Shanahan, L., Hill, S. N., Gaydosh, L. M., Steinhoff, A., Costello, E. J., Dodge, K. A., Harris, K. M., & Copeland, W. E. (2019). Does despair really kill? A roadmap for an evidence-based answer. American Journal of Public Health, 109(6), 854–858.

Shaw, W., Naranjo, R., Neufeld, P., Goretzki, J., Revell, J., & Statters, R. (n.d.). Bridging the Financial Vulnerability Gap. Retrieved on March 6, 2023, from https://www.ey-seren.com/insights/bridging-financial-vulnerability-gap/

Shultz, C. J., & Holbrook, M. B. (2009). The paradoxical relationships between marketing and vulnerability. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 28(1), 124–127.

Singh, P. K., & Chudasama, H. (2020). Evaluating poverty alleviation strategies in a developing country. PLoS ONE, 15(1), e0227176.