Abstract

Business-to-business (B2B) practitioners are increasingly interested in capabilities to holistically manage touchpoints along B2B customer journeys (CJs) to remain competitive. Research in the B2B context, however, has investigated neither what constitutes such a customer journey management capability (CJMC) nor how, whether, or when it creates value. Taking a mixed-methods approach, we conceptualize and operationalize B2B CJMC as a supplier's ability to achieve superior customer value along the B2B CJ by strategically creating value-anchored customer touchpoints characterized through the implementation of consistent resource usage across internal organizational boundaries and by continuously monitoring value creation toward the individual members of the buying center. Analyzing a multisource dataset, we provide evidence that B2B CJMC has an indirect effect on firm performance (i.e., return on sales) through two opposing mechanisms (i.e., customer loyalty and customer-related coordination costs). Importantly, using survey and archival data, we show that, overall, B2B CJMC has a significant and positive impact on firm performance through the two mechanisms. Finally, these underlying mechanisms are also prevalent when testing for the moderating factors switching costs, number of touchpoints, and product versus service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Spurred by a tremendously changing business-to-business (B2B) landscape (Ahearne et al., 2022; Steward et al., 2019), the notion of customer journey management (CJM) is gaining momentum in firms (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Witell et al., 2020). CJM focuses on the design, composition, and order of touchpoints in the customer journey (CJ)Footnote 1 to create value (Kuehnl et al., 2019). As such, marketers are now spending almost one-fifth of their overall marketing budget on initiatives that improve the customer experience, such as CJM, and this share is expected to rise over the next years (The CMO Survey, 2020).

Despite these significant investments, the institutionalization challenges of CJM in B2B markets appear enormous, as nearly 80% of B2B suppliers fail to achieve the expected return on investment (ROI) and clearly lag behind business-to-consumer (B2C) companies, leading to misaligned marketing spend (Maechler et al., 2016; Wiersema, 2013; Wollan et al., 2015). Initial evidence from the non-academic environment suggests that some B2B suppliers are more successful than others because of a superior customer journey management capability (CJMC)—that is, idiosyncratic CJM-related organizational processes that drive customer (e.g., loyalty) and firm (e.g., profitability) performance (Böringer et al., 2019; Caylar et al., 2018; Maechler et al., 2017) through the effective exploitation of organizational resources. For example, the results of a recent survey among 340 chief marketing officers (CMOs) reveal that one of the most important strategic priorities for driving further customer and firm performance is developing a necessary CJMC that integrates touchpoints across the entire CJ, particularly in B2B markets (The CMO Survey, 2019).

Although especially in B2B markets managers need to develop foundational capabilities that enable their firms to manage customer touchpoints in increasingly digital and dynamic environments (Mora Cortez & Johnston, 2017), empirical research in this area is scarce. A review of the CJ field reveals that research “streams provide a limited understanding of B2B [CJM]” (Rusthollkarhu et al., 2022, p. 242) because they do not provide broad and strategic guidance on CJMC to firms (McColl-Kennedy et al., 2019; Ulaga, 2018) (see Table 1).

More precisely, the literature relevant to this study essentially falls into two main categories. The first category has a rather narrow scope, investigating CJM-related aspects through very specific practices, such as CJ mapping (Anderl et al., 2016a) or touchpoint outsourcing in the CJ (Kranzbühler et al., 2019), in specific B2C industries (e.g., retail). Despite valuable contributions, these studies provide only limited insights into a general CJMC, let alone the resulting consequences or potential contingency factors, as the studies are context-specific without providing a comprehensive conceptualization or operationalization of the focal construct. As a result, studying a plethora of narrow CJM-related aspects in B2C markets limits comparability and disciplinary maturity of research and leaves B2B managers with high uncertainty as to which CJMC is essential for competitive advantage.

The second category comprises studies that adopt a broader scope on CJM-related aspects. However, this research is subject to some limitations. Specifically, Lemon and Verhoef’s (2016) conceptual study aggregates existing findings on CJM to provide an integrated perspective and areas for future research. As such, the study mentions specific capabilities (e.g., customer analytics) but does not provide an idea of an overall CJMC. Furthermore, Homburg et al. (2017) present a grounded theory of customer experience management, referring to CJM as a second-order capability represented by four underlying dimensions. However, they conduct interviews with representatives of companies operating exclusively in B2C markets (e.g., retailing,); consequently, considering that literature has revealed key differences in experience-related customer needs between B2C and B2B markets (Lemke et al., 2011), their study of underlying aspects of CJMC is consumer-focused (e.g., lifestyle-based storytelling), neglecting specific B2B characteristics. This B2C limitation also applies to the study of Kuehnl et al. (2019), who take three of the four CJMC dimensions of Homburg et al.’s (2017) examination to investigate an effective CJ design by using consumer data. As a result, that study is limited to a branding context from the consumer perspective.

Taken together, although up to 90% of global revenues are generated in B2B markets (Lilien, 2016), prior CJ “literature has almost exclusively focused on consumer markets [and therefore does] not provide sufficient background for academic endeavours in the industrial and B2B setting, nor [does it] give B2B practitioners tools to manage their customers’ journeys” (Rusthollkarhu et al., 2021, p. 2). Specifically, prior work has provided neither a conceptual nor an empirically substantiated understanding of a broad CJMC that enables suppliers to create value in a B2B environment. More precisely, studies have exclusively investigated single customer-related bright sides (e.g., conversion), at the expense of potential dark sides that might mitigate value creation and thus explain the high failure rate in B2B markets. Exacerbating this fragmented understanding, research provides insufficient support for the fundamental proposition that CJMC improves firm performance. These are important oversights, as there is no empirical evidence of whether CJMC in B2B markets actually creates value for customers and suppliers, let alone under which conditions (see Table 1).

Thus, the lack of CJMC constitutes a major research gap and multiple calls for research, such as the top research priorities of the Marketing Science Institute (2016, 2018, 2020), repeatedly underpin the academic and managerial relevance of this research inquiry. For example, Ulaga (2018, p. 81) notes that the creation and measurement of “superior competitive advantage through [CJMC in B2B markets] still represents a vastly under-researched domain.”As a consequence, various authors have urged scholars to extend the literature by deepening the understanding of the consequences of B2B CJMC and showing that it finally leads to stronger firm performance (e.g., Becker & Jaakkola, 2020; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Moreover, as Mittal and Sridhar (2020) note, managerially relevant boundary conditions in the B2B context that may affect the effectiveness of CJMC have thus far received scant research attention.

We leverage these research opportunities and derive four critical research questions: (1) How can B2B CJMC be conceptualized and operationalized? (2) What are the bright and dark sides of B2B CJMC? (3) Does B2B CJMC pay off? and (4) When does B2B CJMC pay off? We address these research questions using a mixed-method research design (Davis et al., 2011) and contribute to marketing literature in three important ways.

First, we provide a theoretically sound conceptualization and operationalization of B2B CJMC. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to address what CJMC is about in the context of B2B markets. To conceptualize B2B CJMC, we combine interview- and workshop-based insights with literature-based insights from customer experience- and B2B-related literature. Specifically, we identify B2B CJMC as a multidimensional construct that manifests itself in four complementary capabilities: (1) value anchoring of touchpoints, (2) consistency of touchpoints, (3) internal integration of touchpoints, and (4) individual control of touchpoints. We build on these findings and develop an empirically sound measurement scale for B2B CJMC by drawing on survey data. Importantly, we also present a short scale of B2B CJMC that might serve as a standard for future research and managerial adoption. Both scales are industry-spanning and easy to administer. B2B practitioners can use the scales to establish, evaluate, and detect potential deficits in their firms’ CJMC. In studying B2B CJMC, we address recent calls in strategic marketing that urge scholars to “operate in emerging, less-developed research areas” (Yadav, 2018, p. 361) to introduce new constructs that are “broad in scope” and “significant for marketing practice” (Jaworski, 2018, pp. 2–3).

Second, we examine how and whether B2B CJMC contributes to financial firm performance by using primary and secondary data. More precisely, we investigate two opposing underlying mechanisms of B2B CJMC on financial firm performance—one bright mechanism (i.e., CJMC ➔ customer loyalty ➔ return on sales (ROS)) and one dark mechanism (i.e., CJMC ➔ customer-related coordination costs ➔ ROS). As such, we extend existing studies that only investigate positive consequences by also examining a downside of B2B CJMC. Notably, we show that B2B CJMC indirectly affects objective firm performance through these two mechanisms and, more importantly, has a positive overall impact on it. By shedding light on these mechanisms, this study helps B2B managers better understand the implications of CJMC and provides clear strategic directions to value creation. Furthermore, when uncertain about which CJMCs suppliers should invest in, our results provide B2B managers with an empirically substantiated basis for more profitable resource allocations.

Third, we investigate managerially relevant boundary conditions of the dark and bright sides, thus answering when B2B CJMC pays off. Consequently, unlike most previous studies, we propose moderating effects to provide a more fine-grained understanding of B2B CJMC’s value relevance—moderating effects related to dynamism and firm type. Importantly, in our moderator choice, we draw from relevant B2C literature and transfer and extend the findings to the B2B context. We find that a customer’s switching costs (i.e., external dynamism) positively moderates the CJMC–customer loyalty relationship. Furthermore, we show that a supplier’s number of touchpoints (i.e., internal dynamism) positively moderates the CJMC–customer loyalty and CJMC–customer-related coordination costs relationships. Finally, we show that a supplier’s product (vs. service) focus (i.e., firm type) negatively affects both the CJMC–customer loyalty and CJMC–customer-related coordination costs relationship. Given that managers are under increasing pressure to show that their business investments pay off, we offer a more nuanced understanding of how to promote the bright side and mitigate the dark side of CJMC than work that treats CJM as a universal route to competitive advantage.

Theoretical background

The resource-based view (RBV) of the firm provides the overarching theoretical foundation for the conceptualization of B2B CJMC and the conceptual framework of this study. According to the RBV, firms possess idiosyncratic bundles of resources that lead to performance differences between firms through the extent of their exploitation (Barney, 1991). To be more precise, according to the RBV, these performance differences depend on the degree of the existence and usage of firm capabilities. Capabilities are complex bundles of skills and accumulated knowledge, exercised through organizational processes (Day, 1994), that enable firms to achieve competitive advantage through the effective transformation of organizational resources (i.e., input) into increased customer and/or firm performance (i.e., output) (Grant, 1996). In this context, we pay particular research attention to “dynamic capabilities,” which are organizational processes that help firms integrate, reconfigure, gain, and release resources to match and even create market change (Schilke et al., 2018). Dynamic capabilities are inherently transformative as they offer the potential to continuously alter firms’ resource base in new and different ways. Thus, dynamic capabilities are directed to change and enable firms to adapt to dynamic market environments and ultimately achieve superior performance (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece et al., 1997).

Accordingly, scholars argue that the capabilities perspective is a powerful lens for examining the management of customer touchpoints in increasingly dynamic environments (e.g., Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). More precisely, scholars contend that the continuous transformation process of shaping and reshaping touchpoints in the CJ “must be understood as a dynamic capability” (Homburg et al., 2017, p. 387). In a nutshell, dynamic capabilities are critical to managing touchpoints in dynamic CJs to achieve and sustain long-term competitiveness (Kannan & Li, 2017; Wielgos et al., 2021).

Conceptualizing B2B CJMC

For the conceptualization of B2B CJMC, we followed the approach of prior scale development studies (e.g., Brakus et al., 2009; Panagopoulos et al., 2017; Ulaga & Eggert, 2006) and therefore conducted a literature review as the starting point, engaged in in-depth interviews, and held a manager workshop to extend and validate existing findings. These steps helped us gain a profound understanding of B2B CJMC, resulting in the identification of four complementary dimensions and their components.

The concept of CJs and its management

As a first part of the literature review, we initially drew from studies in the fields of touchpoint, CJ, and customer experience (management) (e.g., Barann et al., 2022; Homburg et al., 2017; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). This step guaranteed a proper consideration and integration of existing conceptual findings on CJs and CJM for the development of our B2B CJMC and also set the foundation for the later in-depth interviews.

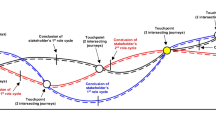

The concept of CJs is customer-facing and comprises the cross-channel touchpoints that a customer uses from pre-purchase to post-purchase. Thus, a CJ consists of three stages (pre-purchase, purchase, and post-purchase) that can vary in length and the type and extent of touchpoints used (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). These stages are commonly recursive, unless for a one-time purchase, which is why repeating CJs may—again—vary as the customer uses other or more/fewer touchpoints in a specific stage or the entire CJ. Accordingly, against this phasic and recursive background, the concept of CJs is dynamic rather than static (Kranzbühler et al., 2018). Conceptually, the CJ is embedded within the overarching concept of customer experience, which includes every aspect of a firm’s offering and is the sum of all interactions that have taken place at touchpoints (Kranzbühler et al., 2019). Here, touchpoints function as stimuli for customer experience responses and as means through which the firm and the customer engage (Neslin et al., 2006), finally resulting in evaluative customer outcomes (Becker & Jaakkola, 2020). Consequently, in this theoretical reasoning, the customer experience is the sum of all customer responses to interactions that have occurred at touchpoints along one or more CJs up to the present time (Kranzbühler et al., 2018).

By contrast, the concept of CJM is supplier-facing and, thus, a constituent part of customer experience management (Homburg et al., 2017). Whereas customer experience management takes a broader perspective and, beyond CJ-related aspects, also focuses on, for example, how new technologies can improve the customer experience, CJM focuses on the design, composition, and order of touchpoints in the CJ to contribute to positive evaluative outcomes of the customer experience (Kuehnl et al., 2019). More precisely, CJM mainly centers on firm-owned touchpoints that are directly controlled by a supplier (e.g., product-related), compared with customer-owned (e.g., word-of-mouth-related) or third-party-owned (e.g., media-related) touchpoints that are outside its direct control (Baxendale et al., 2015).

Contrasting B2B and B2C CJs

As a second part of the literature review, we followed the idea that the characteristics of B2B CJs act as the main action object of B2B CJMC. In doing so, we considered B2B studies that unpack four unique and managerially relevant characteristics of B2B CJs missing in B2C-focused examinations.

The first characteristic refers to the economic reason for touchpoint usage. More precisely, the primary interest of any B2B firm is to strengthen its competitiveness and generate economic added value (Ulaga, 2003), in an effort to satisfy the demand of its own customers (Grewal et al., 2015). Consequently, B2B customers use touchpoints primarily with the expectation that these will contribute to economic value generation. B2C customers, by contrast, tend to use touchpoints more for hedonistic reasons, such as pleasure or enjoyment (Schmitt et al., 2015). As a result, B2B CJs are rationally oriented, whereas B2C CJs are more perceptually and emotionally oriented, characterized by impulsively used touchpoints (Lilien, 2016). The second characteristic refers to the presence of mutual dependency in long-term buyer–supplier relationships that are contractually regulated from high monetary and non-monetary investments. As such, the two parties have higher switching costs and less room to maneuver than those in B2C markets, in which contractual business relationships play only a subordinate role and can be more easily dissolved by the customer (Johnson & Sohi, 2016). As a result, B2B CJs are more repetitive than B2C CJs and contain more touchpoints that need to comply with contractual conditions. The third characteristic refers to the multi-personality in B2B buying, that is, the involvement of multiple people from different departments with different functions and skills. Whereas multi-person decision-making is the exception in the B2C context (e.g., families), it is the norm in the B2B context, which is why B2B CJs consist of touchpoints used by a wide variety of people in parallel with or across the different phases of the CJ (Grewal & Sridhar, 2021). Against this background, B2B CJs comprise touchpoints used by different members of the buying center who are physically and temporally separated from one another but also have different expectations of these touchpoints (Ahearne et al., 2022). The fourth characteristic refers to the complexity of interactions in B2B relationships, as standardized solutions can rarely be offered across heterogeneous B2B customers (Worm et al., 2017). Rather, individual solutions that are commonly co-created are required (Petri & Jacob, 2016). Therefore, various interactions take place via diverse on- and offline channels at personal and impersonal touchpoints. As a result, B2B CJs are more complex—they are longer, contain more channels, and consist of more diverse technical and personal touchpoints—than B2C CJs (Witell et al., 2020).

Qualitative study 1: Manager interviews

After the literature review, we conducted a qualitative study to develop an industry-spanning conceptualization of B2B CJMC. Web Appendix A provides the sample characteristics.

Sampling procedure and characteristics

We gathered data through in-depth interviews with European B2B managers working at the customer–supplier interface. Experts were contacted through an international professional network and an international business conference. We ceased the sampling process when no new insights emerged from the field data—that is, when we reached theoretical saturation (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Our final sample consisted of 38 respondents, which is in line with the sample size recommended for exploratory research purposes (McCracken, 1988). To develop an industry-spanning conceptualization, we maximized the diversity and included suppliers of different firm sizes and from different industries and value chain positions in the sample. Overall, our managers had extensive work experience (i.e., 19 years on average) and were key B2B decision-makers.

Interview guide

Our interview guide consisted of three sections. The first section pertained to characteristics of the respondent and the firm. The second section addressed the concept of B2B CJs and their management. In this main part of the interview, we encouraged respondents to offer examples, anecdotes, and additional details on potentially important issues (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This allowed us to interpret the resulting data with the necessary integrity, reducing the potential threat of misinterpretations (Wallendorf & Belk, 1989). In the third section, we asked the respondents for their opinions, examples, and clarifications and gave them the opportunity to address other points they considered important. Overall, we carefully phrased the questions in a non-directive manner to avoid “active listening” and also did not explicitly mention our theoretical underpinning of B2B CJM as a capability (McCracken, 1988). Web Appendix B lists the interview guide used.

Analysis and interpretation

The in-depth interviews lasted 50 minutes, on average, with a range between 38 and 61 minutes. We audiotaped each interview and transcribed the data verbatim. To analyze the data, two independent researchers employed well-established iterative coding procedures using the software MAXQDA (Gioia et al., 2013). First, they identified several first-order categories through line-by-line analysis, which they then organized into second-order themes. Second, they aggregated these themes into overarching dimensions representing the B2B CJMC dimensions. Following prior capability research, our goal was “to capture the essence, or fundamental core, of the capability [i.e., B2B CJMC] at a higher level of generalization and abstraction” (Sarkar et al., 2009, p. 587).

Trustworthiness assessment

To ensure the trustworthiness of the results, we applied principles of data and theory triangulation (i.e., literature, interviews, and focus group) (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). According to the principle of refutability as a quality criterion of qualitative research (Silverman & Marvasti, 2008), we sought to refute the coding results by obtaining a broad and diverse sample. We observed that most of our results were transferable to a cross-industry B2B context. To further enhance the confirmability of our results (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), we asked two independent researchers unaware of the study’s purpose to code the verbatim data of 19 randomly selected interviews into the coded categories. Intercoder reliability, assessed according to the proportional reduction in loss measure, reached .75 and thus is above the .70 threshold for exploratory research (Rust & Cooil, 1994). To further improve content validity, we presented the research results in a manager workshop with nine participants from different industries and a duration of 150 minutes (see Web Appendix A). Participants were asked to provide verbal and written feedback on the ideas, and video, audio, and verbal protocols were prepared by two additional research assistants during the session. From this feedback, we redeveloped and refined unclear definitions and formulations of our B2B CJMC dimensions and the underlying aspects (Zeithaml et al., 2020).

B2B CJMC and its dimensions

Informed by our results, we propose a parsimonious conceptualization of B2B CJMC. Specifically, B2B CJMC comprises four complementary capabilities that address the identified unique characteristics of B2B CJs across all stages; that is, they refer to aspects that are relevant to all firm-owned touchpoints along the entire B2B CJ.

Value anchoring of touchpoints

Our managerial insights reveal that the development of a superior CJ begins with the deep anchoring of customer value at touchpoints. In accordance with prior research, we conceptualize this dimension as a strategic capability that leverages the creation, but also the comprehensible and straightforward communication, of what superior business value a touchpoint offers a targeted customer (i.e., customer value proposition) (Payne et al., 2017). Thus, we define value anchoring of touchpoints as the degree to which a supplier aims to create value by rooting every touchpoint along the B2B CJ in a transparent and strategically aligned customer value proposition.

Our interviewed suppliers noted the need for this capability because the involvement of several people and departments in interactions leads to the risk that touchpoints will be misleadingly designed, conveying a false or no customer value proposition. Furthermore, the managers indicated that ever-faster changing needs (e.g., through technological innovations) of diverse B2B customers exacerbate the challenge of mis- or non-aligned touchpoints. As such, we derive three main elements of this dimension from managerial and research insights. First, value anchoring of touchpoints requires that suppliers have a fundamental knowledge of customers and their business model “to understand and articulate how their goods and services will affect customers’ operations and create value” (Payne et al., 2017, p. 476). Second, value creation (i.e., improving a customer’s competitiveness) lies at the core of this dimension by designing and adapting touchpoints to create customer benefits or reduce customer costs (Ulaga & Eggert, 2006). Importantly, this value creation process is dynamic, as needs may vary along the B2B CJ or change over time (Frow et al., 2014). Third, suppliers need to transparently communicate the offered value to close a potential gap between customers’ expected and experienced value of a touchpoint (Eggert et al., 2019). Summarizing this tripartite of value anchoring of touchpoints (i.e., understanding, creating, and communicating), a vice president of sales for an IT and electronics supplier stated:

Once a year, we conduct a customer survey, workshop, and customer observations to identify the 100 most important touchpoints and their “is of use” from a customer perspective. Based on these findings, first, we define for each of these touchpoints the customer value that should be created and communicated, and second, we design or adapt these touchpoints toward this desired value. As a consequence of last year’s findings, for example, we redesigned our app to focus more on an efficient ordering process or expanded the technical product information on our website. Conducting this customer data collection annually helps us to see if customers' needs toward customer touchpoints change over time.

Thus, despite complex and dynamic B2B CJs, this capability enables every touchpoint to be conducive to the overall aim of economic customer value creation.

Consistency of touchpoints

The in-depth interviews repeatedly showed that suppliers need to keep aspects such as quality, information content, cooperate identity, and interaction behavior constant across all touchpoints and along repetitive CJs to deliver lasting customer value. Following branding research (e.g., Beverland et al., 2015; Iyer et al., 2021), we conceptualize consistency of touchpoints as a capability and define it as the degree to which a supplier delivers uniform touchpoints along the B2B CJ from a customer's viewpoint.

Our consulted managers emphasized the need for this dimension to avoid customer confusion or contractual penalties due to deviating touchpoints. As the CMO of a transport and logistics provider explained:

From the customer's perspective, despite complex B2B buying processes and the fact that multiple buying center people are involved within the CJ, there is an expectation of consistent touchpoints during the CJ. However, different internal owners can cause inconsistent touchpoints. Thus, it is important to take a longitudinal view of the total CJ to spot inconsistency, and you have to raise questions such as: Are my customers getting the same quality and message from our business in our web store, as they are on the phone with our agents or via email?

Echoing this quote, consistency of touchpoints requires taking an outside-in perspective to gain an understanding of how the customer, not the supplier, perceives marketing activities at touchpoints (Day, 1994). Similarly, this dimension calls for a cumulative unified view of the B2B CJ and thus needs to set value propositions at touchpoints in the context of a coherent CJ rather than in isolation (Zablah et al., 2004). In general, consistency signals a supplier’s commitment to a customer and can enhance the effectiveness of the interaction process (Dwyer et al., 1987). Moreover, from a customer's perspective, consistency is critical to the efficient use of touchpoints, as a customer can assume that touchpoints are coherent over time, rather than misleading or even contradictory, minimizing further search or control costs and improving performance reliability. It is also important to stress that value consistency does not refer to a regulated uniformity of or an unwillingness to change touchpoints. That is, this dimension is not about achieving static consistency but about being consistent yet dynamic in response to changing or different customer needs (Zablah et al., 2004).

Internal integration of touchpoints

The data reveal that suppliers need to amalgamate internal resources in the B2B CJ to deliver customer value. Similarly, marketing academics have recognized that providing a “positive customer experience requires minimally the integration of myriad suppliers' functions, such as operations, logistics, marketing, and sales” (Mora Cortez & Johnston, 2017, p. 97). In line with prior research focusing on internal integration (e.g., Day, 1994; Jerez-Gómez et al., 2005), we conceptualize this dimension as a capability and adapt Homburg et al.’s (2017) findings to our research context to define internal integration of touchpoints as the degree to which a supplier functionally integrates touchpoints across online and offline channels to deliver seamless transitions in the B2B CJ.

Our managers underscored the importance of this dimension due to the increase of digital touchpoints and also because many suppliers suffer from siloed organizational systems, leading to considerable integration challenges. Thus, to offer intertwined business processes, integrating touchpoints across digital and non-digital channels and departments is crucial. In this context, the head of customer experience of an automotive supplier noted:

In our business, the delivering of satisfactory CJs essentially requires that information on touchpoint usage is collected and merged across channels and departments.… To handle projects efficiently and without a loss of information, we therefore depict past interactions in an integrated customer experience tool to get a holistic perspective on the touchpoints used and the transitions between them.

Following this example, intertwined touchpoints in the B2B CJ require a systematic approach that considers all, not just individual, touchpoints (Chang & Li, 2022). More specifically, first, it is imperative to collect and integrate customer-related data at every touchpoint throughout on- and offline channels, including back-end (e.g., supply chain) and front-end (e.g., sales reps) touchpoints (Holmlund et al., 2020). Second, it is mandatory to amalgamate and bundle these data. For this, our suppliers noted that aligning internal interfaces to facilitate and foster data and knowledge exchange within complex organizational structures is fundamental to gaining an integrated CJ perspective. Similarly, marketing scholars acknowledge that interdepartmental integration leads to connected and more coordinated touchpoints (Braunscheidel & Suresh, 2009; Homburg et al., 2017). Third, managers noted that this capability comprises the depiction of touchpoints to enable a holistic view of the sophisticated B2B CJ. Such a mapping of touchpoints enables a firm-spanning perspective to develop seamless customer business processes and acts as a promising starting point to identify customer pain points along the B2B CJ (McColl-Kennedy et al., 2019).

Individual control of touchpoints

Finally, managers consistently emphasized the need for control systems that examine value generation in the B2B CJ against the individual needs of the interaction partner. We follow literature in the field of individual interactions to conceptualize this dimension as a capability (e.g., Ramani & Kumar, 2008). More precisely, we define individual control of touchpoints as the degree to which a supplier monitors value creation of touchpoints in the B2B CJ toward the member of the buying center.

Our data reveal the importance of this dimension, as the overall B2B CJ consists of many individual touchpoints with members of the buying center who have different tasks, skills, and interests (Grewal & Sridhar, 2021; Witell et al., 2020). Therefore, to address multi-personal needs and avoid mismatched touchpoint allocations, this dimension begins with the individual employees who ultimately use touchpoints as the unit of analysis in the B2B CJ (Hoekstra et al., 1999; Ramani & Kumar, 2008). From our data analysis, this dimension includes the three major components of identifying respective buying center members at each touchpoint, tailoring touchpoints to their needs, and analyzing their touchpoint-related responses. More precisely, this dimension reflects the capability to identify heterogeneous buying center members throughout the B2B CJ and to offer customized touchpoints by possessing information about the respective buying center members, incorporating feedback from previous responses, and predicting future needs. As the head of sales of a chemical supplier applying a buying center-related touchpoint approach remarked:

We are backing up all touchpoints, based on an ongoing data collection and analysis, to identify the respective touchpoint users and their buying center-related functions and needs. We are doing this because individual needs, skills, or terminologies used are differing tremendously. The focus on the touchpoint-related reactions fosters insights on how to further adapt our customer touchpoints to the buyer, technician, or product user, for example.

As a consequence, this capability leads to greater effectiveness and efficiency of customer interactions, as touchpoints can be more informative, convenient, or flexible.

Building on the preceding conceptualization of its first-order dimensions, we define B2B CJMC as a supplier's ability to achieve superior customer value along the B2B CJ by strategically creating value-anchored customer touchpoints characterized through the implementation of consistent resource usage across internal organizational boundaries and by continuously monitoring value creation toward the individual members of the buying center. Importantly, the conceptualization as a multidimensional construct implies that “all dimensions are necessary for the successful implementation” (Kuehnl et al., 2019, p. 554) of the second-order construct simultaneously, as we show in more detail next.

B2B CJMC as a dynamic capability

Following Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), we argue that B2B CJMC is a dynamic capability because (1) it reflects a set of specific and identifiable capabilities, (2) its effective deployment depends on the complementarities among these capabilities, (3) it exhibits common features across suppliers but is idiosyncratic in its details, and (4) its effectiveness may depend on environmental dynamism. First, B2B CJMC reflects four specific and identifiable first-order dimensions that cannot be easily duplicated by competing firms.

Second, B2B CJMC’s effective deployment depends on the complementarities among these four dimensions, with success in all dimensions necessary to achieve superior performance. This is because firms need to simultaneously create (i.e., value anchoring), implement (i.e., consistency and internal integration), and monitor (i.e., individual control) customer value at touchpoints to achieve new forms of value in the CJ (e.g., Homburg et al., 2017). Specifically, value anchoring involves the formation of value-creating strategic responses to managing touchpoints in B2B CJs, such as the specification of cost reduction or benefits generation. As “strategies only result in superior returns for an organization when they are implemented successfully” (Noble & Mokwa, 1999, p. 57), suppliers must constantly align their resources with strategic goals to foster value anchoring of touchpoints’ implementation success (Jacob et al., 2021). In this context, consistency and internal integration are critical to realizing the value-creating potential of value-anchored touchpoints. Finally, managers must regularly assess the performance of these implementation efforts against strategic goals to take corrective action if necessary (Verhoef et al., 2021). Such an assessment is achieved through individual control of touchpoints, which adopts a customer-distinct perspective and enables suppliers to monitor value creation by analyzing customer responses and future needs related to their strategic approaches. In this way, suppliers can continuously reinvent their strategic approach of value anchoring of touchpoints by incorporating learnings from ongoing implementation efforts and by adapting strategic responses to customer requirements. As such, we argue that with the effective deployment of B2B CJMC, a supplier will exhibit each of the four dimensions to a great extent.

Third, best practices can be derived for the incorporation of B2B CJMC, such as ensuring consistent touchpoints along personal and impersonal touchpoints. Despite these common features across suppliers, however, the concrete manifestation of B2B CJMC is typically idiosyncratic in firms. For example, our data reveal that suppliers at the beginning of the value chain focus more on consistent efficiency while suppliers at the end of the value chain focus more on consistent experiential responses to touchpoints.

Fourth, we argue that the effectiveness of B2B CJMC varies with dynamism in the firm environment, as put forth in our “Hypotheses development” section. Taken together, we argue that B2B CJMC is a dynamic capability that has the potential to significantly increase the sustainability of competitive advantage because it is time- and cost-intensive to develop and thus exceedingly difficult for competitors to imitate (Kozlenkova et al., 2014).

Conceptual model

Our conceptual model (see Fig. 1) is rooted in the RBV, the central premise of which is that capabilities are the most critical driver of sustainable competitive advantage. Most studies propose universally positive outcomes of capabilities but neglect to investigate negative consequences, such as costs related to the development, implementation, and maintenance of these capabilities (Rohani et al., 2021). Therefore, to provide a more nuanced understanding, we examine a bright and also a dark side of B2B CJMC, including the overall effects of these opposing mechanisms on a supplier’s financial performance (i.e., ROS).

On the one hand, we focus on investigating one of the most prevalent constructs in marketing research and practice reflecting a bright side of a supplier’s resource usage: customer loyalty (Katsikeas et al., 2016). Customer loyalty captures a customer’s overall attachment or deep commitment to a supplier’s touchpoints. The construct describes the expressed preference to engage again in a journey of touchpoints provided by a given firm (Herhausen et al., 2019; Zeithaml et al., 1996) and to deepen the relationship by using additional touchpoints, resulting in an ongoing loyalty loop (Siebert et al., 2020). As a consequence, customer loyalty focuses on the customer’s intrinsic inclination to choose a firm’s overall touchpoints in a CJ over alternatives. Thus, it is critical for business success and a long-term predictor of a supplier’s financial performance (Gupta & Zeithaml, 2006).

On the other hand, we focus on customer-related coordination costs as a dark side of B2B CJMC. Customer-related coordination costs are a supplier's internal coordination, communication, collaboration, decision-making, and information processing efforts required for customer interactions at touchpoints in the B2B CJ. Consequently, customer-related coordination costs lower a supplier’s financial performance (Lee et al., 2015).

Furthermore, we aim to provide actionable insights when B2B CJMC is more or less valuable, as our interviewed managers revealed that they are under increasing pressure to demonstrate the financial accountability of their CJM-related practices. This endeavor is also theoretically relevant, as researchers argue that dynamic capabilities are critical to remaining competitive in managing CJ—a fact that has so far been neglected to empirically investigate in a B2B context. To do so, we rely on the contingent RBV (e.g., Aragón-Correa & Sharma, 2003) in general and particularly on Barreto (2010), who identifies two fundamental categories of moderators for dynamic capabilities: (1) dynamism and (2) firm type.

First, one ongoing debate about dynamic capabilities pertains to their effectiveness under different degrees of dynamism. Some researchers suggest that dynamic capabilities are particularly valuable in the context of high dynamism (Teece et al., 1997), while others argue that their effectiveness may diminish when firms face high levels of dynamism (Schilke, 2014). Thus, from a theoretical perspective, the fundamental proposition that dynamic capabilities enable firms to cope with the challenge of managing the dynamics of CJs remains questionable. To shed light on this issue, we consider managerially relevant moderators related to external (i.e., switching costs) and internal (i.e., number of touchpoints) dynamism.

Switching costs “refer to the buyer’s perceived costs of switching from the existing to a new supplier” (Wathne et al., 2001, p. 56) and narrow a customer's room to maneuver, thus contributing directly to a reduction of external dynamism. In relevant literature, switching costs are a prominent moderator to explain customer loyalty (Kuehnl et al., 2019; Lam et al., 2004) and coordination effects (Kim et al., 2009). Number of touchpoints represents the quantity of supplier-controlled touchpoints compared with competitors. With a high number of touchpoints, suppliers face the challenge of aligning and monitoring them on an ongoing basis (Gentile et al., 2007; Verhoef et al., 2021), which increases the frequent change of organizational resources and processes—that is, internal dynamism (Homburg et al., 2008). Although the impact of the number of touchpoints is highly relevant from a practical standpoint, this aspect has hardly been studied in related literature (see Table 1), which is why we investigate it as an important moderator to explain the effectiveness of B2B CJMC.

Second, research highlights varying effects of dynamic capabilities on firm performance across different types of firms (Barreto, 2010). Especially in the B2B context, marketing scholars typically rely on the differentiation of firms operating in a product or service context (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2009; Parvinen et al., 2013). Fundamental differences between these two contexts mainly stem from the lesser complexity of tangible characteristics of products than services. These differences may affect the value creation potential of holistic touchpoint management (Kuehnl et al., 2019). Against this background, we aim to shed further light on the effectiveness of B2B CJMC for product- versus service-focused firms.

Hypotheses development

Bright side: Effect of B2B CJMC on customer loyalty

In line with the RBV and our qualitative data, we argue that B2B CJMC creates superior customer value (e.g., Flint et al., 2011) by encouraging not only short-term sales but also long-term customer loyalty for two main reasons. First, B2B CJMC ensures the transparent creation of business value through persistent yet dynamic responses over time and across departments, channels, and buying center members. Here, the creation of enduring customer value is considered one of the most important tasks in marketing to attain lasting customer loyalty (Kumar & Reinartz, 2016). Second, B2B CJMC smooths and facilitates the transition between touchpoints. Delivering such seamless experiences is considered a crucial aspect in increasingly digitalized markets to foster customers’ intention to repeatedly progress through a CJ from pre-purchase to post-purchase (Chang & Li, 2022). Taken together, B2B CJMC “function[s] as a value driver […] to a favorable customer experience” (Kuehnl et al., 2019, p. 556) that customers wish to repeat (Brakus et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2020). Thus:

H1

B2B CJMC positively affects customer loyalty.

Dark side: Effect of B2B CJMC on customer-related coordination costs

We contend that B2B CJMC also has a dark side through increased customer-related coordination costs. In line with the RBV and our interview insights, we argue that the implementation and maintenance of B2B CJMC involve substantial costs that arise from the generation of new resource configurations through resource integration, resource acquisition, or their combination (Helfat & Winter, 2011; Schilke, 2014; Winter, 2003). More precisely, the institutionalization of B2B CJMC incurs extensive costs because it entails high customer-related coordination costs, which require combining resources across functions, hierarchies, and departmental boundaries (Ritter, 2020). As a vice president of sales at an electronics supplier said about the development of coordination efforts:

The more intensively we have promoted a holistic touchpoint management in recent years, the more our coordination effort has increased. Initially, the focus was mainly on direct front-end touchpoints within the sales funnel to increase the conversion rate of our sales staff. However, when we started to consider customer interactions beyond conversion, we had to increasingly integrate back-end touchpoints. Suddenly, we were talking about integrating processes that included delivery, packaging, or technical support.

Taken together, we hypothesize the following:

H2

B2B CJMC positively affects customer-related coordination costs.

Moderating effect of switching costs

Drawing on the RBV and our managerial insights, we suggest that B2B CJMC's success is greater in relationships with high customer switching costs, due to the reduction of a supplier’s external dynamism. The reduction of external dynamism associated with high switching costs is largely due to the long-term-oriented nature of B2B relationships in this context (Sheth & Shah, 2003). On the one side, customers with high switching costs demand business relationships with many interactions and intense exchange of resources (Rindfleisch & Heide, 1997). Thus, B2B CJMC may be of particular value in this context by promoting diverse customer interactions and resource sharing in CJs (Mies et al., 2021). On the other side, in an environment of high switching costs, customers tend to be more familiar with a supplier’s touchpoints (Burnham et al., 2003), which is why coordination efforts related to B2B CJMC may be diminished, as a CMO of a mechanical engineering firm confirmed:

In our industry, some business relationships tend to be very long-term, as a change would be costly for our customers.... It is precisely for these business relationships that the management of all touchpoints is particularly worthwhile, as the number of interactions is high, but at the same time, our coordination effort is relatively lower [than in] short-term relationships because we know these [customers’] needs quite well.

Combining these insights, we propose that B2B CJMC exerts a stronger effect on customer loyalty but a weaker effect on customer-related coordination costs in B2B relationships, which are characterized by high switching costs. Thus:

H3a

The positive effect of B2B CJMC on customer loyalty is stronger under high switching costs.

H3b

The positive effect of B2B CJMC on customer-related coordination costs is weaker under high switching costs.

Moderating effect of number of touchpoints

Following the RBV and our qualitative insights, we propose that the number of touchpoints fundamentally affects a supplier’s internal dynamism because the higher the number of touchpoints, the more intense and diverse are customer interactions in CJs that need to be managed (Ciasullo et al., 2021; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). From a customer’s perspective, a “higher number of touchpoints in the customer journey is associated with more information sources, a higher variety of information, and a stronger focus on the processing of information” (Herhausen et al., 2019, pp. 13–14). Therefore, under these conditions, we propose that B2B CJMC especially contributes to superior customer value by simplifying touchpoint usage and information processing in the CJ (Steinhoff et al., 2019). However, from a supplier’s point of view, the more touchpoints, the higher is the coordination effort to create, implement, and monitor customer value through B2B CJMC (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Summarizing this reasoning, a logistics provider's vice president of sales development stated:

It became apparent early on that sustainability gains in importance to our customers. As a consequence, we have developed a lot of add-on services such as CO2-neutral packaging or smart containerization. These new touchpoints offer additional benefits to the customer, but they also need to be managed and integrated into existing CJs. That can be quite a challenge.

Accordingly, we argue that a high number of touchpoints will increase the influence of B2B CJMC on customer loyalty but also on customer-related coordination costs. Thus:

H4a

The positive effect of B2B CJMC on customer loyalty is stronger under a high number of touchpoints.

H4b

The positive effect of B2B CJMC on customer-related coordination costs is stronger under a high number of touchpoints.

Moderating effect of product versus service

Suppliers commonly offer products and services simultaneously, but to varying degrees. B2B CJMC can be valuable for suppliers with either focus. However, owing to the multifaceted differences between products and services, the resulting consequences from B2B CJMC may vary between these two types of focus. In general, products are more tangible, are non-perishable, and require less customer participation in the process of development, production, usage, and after-sales than services (Tuli et al., 2007). With fewer interactions with a supplier, greater homogeneity may occur for products than for services (Parasuraman et al., 1985). Consequently, on the one hand, customers may perceive touchpoints related to products as involving less uncertainty, purchase risk, and complexity than services (Zeithaml, 1981). On the other hand, recent studies suggest that in today's digital age, new forms of customer value are being created primarily through service- rather than traditional product-related touchpoints (Ramaswamy & Ozcan, 2018; Wielgos et al., 2021). Therefore, contributing to the reduction of perceived complexity and uncertainty, but also the lower potential of value creation, B2B CJMC may be less essential for products than for services in driving customer loyalty.

In the same vein, a supplier's product focus typically entails offering fewer and simpler touchpoints in the CJ than a supplier with a service focus (Berry et al., 2006). As a result, product-focused suppliers can more easily coordinate resources internally to provide appropriate touchpoints along the CJ than service-focused suppliers (Kuehnl et al., 2019). Underscoring our argumentation, a sales director e-business of a construction supplier stated:

We are increasingly transforming ourselves from a product to a service firm. This creates entirely new customer value but also means that considerably more touchpoints and background processes have to be taken into account. For example, … we provide modular-equipped vehicles to the individual needs of our customers that are fitted with sensors. These sensors measure the consumption of tools, such as screws, and independently reorder the products that the customer has been using.

Against this background, we argue that the influence of B2B CJMC on customer loyalty is less pronounced for suppliers with a product focus than a service focus and that the same holds true for customer-related coordination costs. Thus:

H5a

The positive effect of B2B CJMC on customer loyalty is weaker for firms with a product focus than a service focus.

H5b

The positive effect of B2B CJMC on customer-related coordination costs is weaker for firms with a product focus than a service focus.

Quantitative study 2: Manager survey

Data collection and sample

In our study, the unit of analysis is the strategic business unit (SBU) in a firm (or, if no specialization of different SBUs exists, the entire firm). To obtain the necessary data for testing our industry-spanning conceptualization and our framework, we relied on a large-scale online survey of B2B firms using key informants. Our initial sample consisted of 5,997 firms. We regard these firms as the relevant B2B population, covering 14 industries according to the statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE Rev. 2).

For each firm, we identified potential respondents for various SBUs via social business networks. We selected contacts by filtering by position and work experience (i.e., at least three years in current position). We contacted 5,437 respondents via email, inviting them to a survey of 20 minutes in length. To ensure the reliability of our key informants, we included three items at the end of the questionnaire on the degree of involvement, competence in answering, and overall relevance of the questionnaire. We discarded questionnaires if one of these items was rated lower than 5 on a 7-point scale. As a result, we had 612 questionnaires, for a completion rate of 56.2% (overall response rate: 11.3%).Footnote 2 Importantly, respondents had extensive working experience (i.e., 20.2 years on average) and were key decision-makers.

In addition, we collected archival performance data on the SBU level to test for the effects of B2B CJMC on financial firm performance in our conceptual model. We collected these data (n = 410) from various sources such as databases (e.g., ORBIS), government gazettes, company websites, or asked the interview participants to provide us with their annual reports. Web Appendix C shows the composition of the sample.Footnote 3

Operationalizing B2B CJMC

We developed a theoretically sound B2B CJMC measurement scale using established scale development procedures (Churchill, 1979; MacKenzie et al., 2011). As conceptually derived, B2B CJMC is reflected in the complementarities among its dimensions and thus must be taken as a second-order reflective construct. As Tanriverdi (2006, p. 63) notes, a “formative second-order factor modeling approach is not appropriate for capturing complementarities because it does not assume any interactions or covariance among the first-order factors.” Consequently, we operationalize B2B CJMC as a second-order construct reflected in four first-order dimensions, each of which comprises a set of reflective indicators.Footnote 4

Item pool generation

From our in-depth interviews, a review of relevant conceptual literature (for an overview, see Kuehnl et al., 2019), and B2B scales related to the four CJMC dimensions, we carefully developed a set of items for the individual subdimensions, making sure to cover all essential aspects of the focal construct’s domain (MacKenzie et al., 2011). As a result, we generated a large pool of 49 items for the four dimensions of B2B CJMC.

Item reduction

As a scale with 49 items is not applicable, we further reduced the initial item pool. To do so, we relied on personal judgments of B2B researchers and decision-makers (Ulaga & Eggert, 2006). First, to assess face validity of the item pool, we explained the concept of B2B CJMC and its dimensions to 18 B2B marketing researchers and asked them to assign each item to one of the four introduced dimensions. We conservatively dropped items that did not receive consistent assignment and further refined some items according to the researchers’ suggestions to increase comprehension and relevance (Kuehnl et al., 2019).

Second, to ensure content validity, we presented the remaining items to the nine senior executives in our workshop and also submitted them to a judgment sample of 25 managers. These groups reviewed the items, as well as definitions of the construct and its four dimensions, and rated each item on how well it reflected its corresponding dimension, on a 7-point scale. Subject matter experts also assessed whether items were worded appropriately and were generalizable across industries (Panagopoulos et al., 2017). We retained 26 items.

Measure assessment

We subjected the B2B CJMC scale first to an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and then to a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). On the basis of modification indices, factor loadings (FLs), and model fit statistics, we deleted six items, reducing the scale to 20 items (Panagopoulos et al., 2017). The EFA with the final item pool revealed four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 (variance explained = 65%). In line with our conceptualization, the CFA also confirmed that B2B CJMC is a second-order construct.Footnote 5 Specifically, standardized FLs were all high and significant (p < .01), ranging from .60 to .92 between the first-order factors and the respective indicators and from .62 to .86 between the second-order construct (B2B CJMC) and its four dimensions (see Table 2).

Moreover, the final scale fit the CFA data well (Hu & Bentler, 1999): χ2/df = 2.94; comparative fit index (CFI) = .95; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .94; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .05; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .05. Cronbach’s alphas (CAs), composite reliabilities (CRs), and average variances extracted (AVEs) of the second-order construct and first-order dimensions were all above the required thresholds (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012; Iacobucci, 2010).Footnote 6 These results provide evidence of convergent validity. We assessed and ensured discriminant validity between the first-order dimensions using Fornell and Larcker's (1981) criterion (see Web Appendix D).

Finally, we ran a model comparison to empirically validate our conceptual considerations further (see Table 3). The model comparison indicated that B2B CJMC is a second-order construct. Model 4 in Table 3 shows the best-fit indices and the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values (first- vs. second-order: ΔAIC = 1,697; ΔBIC = 1,699) (Kuehnl et al., 2019). In summary, the EFA, CFA, Fornell–Larcker criterion, and model comparisons clearly indicate that B2B CJMC is a second-order construct comprising four complementary dimensions. Web Appendix E provides a complete list of our measures, their psychographic properties, and AVEs.

Measurement of additional constructs of the conceptual model

Mediating measures

We measured the mediators, customer loyalty and customer-related coordination costs, respectively, with 7-point scales. Specifically, for customer loyalty, our measure consists of three aspects—customer intention to repurchase, customer intention to increase sales volume, and customer word-of-mouth intention—which we measured with six items adapted from Zeithaml et al. (1996). For our construct of customer-related coordination costs, we used five items related to the internal effort of customer interaction (i.e., coordination, communication, collaboration, decision-making, and information processing).

Moderating measures

We measured the two moderators related to dynamism, switching costs and number of touchpoints, with 7-point scales. More precisely, for switching costs, we used three items adapted from Lam et al. (2004) that refer to a customer’s required money, effort, and time to move to another supplier. For the construct of number of touchpoints, we used three items that measure the number of marketing, sales, and service-related supplier-controlled touchpoints compared with competitors. To measure the third moderator related to the firm type, product versus service, managers split average sales for the last three years into product and service sales on a 100-point scale (Antioco et al., 2008).

Performance measure

For the supplier’s firm performance, we measured the three-year industry-adjusted ROS (Homburg et al., 2012a). We did so by subtracting the industry SBU-mean ROS within the last three years from the SBU-mean ROS within the last three years using archival data (n = 325).

Control measures

We controlled for several firm, customer, and market characteristics, to rule out rival alternative explanations (i.e., omitted variable bias) of the investigated consequences of B2B CJMC (Klarmann & Feurer, 2018). First, we controlled for firm size from archival data as the logged number of employees (Worm et al., 2017). Second, we controlled for buyer’s dependence on the supplier and buyer’s power, with respondents rating their customers on single-item 7-point scales (Narver & Slater, 1990; Noordewier et al., 1990). Third, we controlled for the industry’s technological change, with managers assessing it within the last three years on a single-item 7-point scale (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993).

Model assessment and estimation

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations of the variables investigated. To verify the validity of our conceptual model, we conducted several robustness checks.

Common method variance

We applied both a priori (Hulland et al., 2018) and post hoc (e.g., Williams et al., 2010) remedies to reduce the potential risk of common method variance (CMV). First, as a procedural, a priori remedy, our research design reduces the potential risk of CMV, as we used different data sources for the predictor variables and the outcome measures (i.e., survey and archival data) (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Importantly, with respect to the investigated moderating effects, research has shown that these “effects cannot be artifacts of CMV” (Siemsen et al., 2010, p. 456). We also pretested the questionnaire, assured respondents of their anonymity and confidentiality, emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers (to help reduce the possibility of bias due to self-presentation), and arranged items and constructs in random order (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Summers, 2001). Second, as a statistical, post hoc remedy, we used Harman’s single-factor test, the unmeasured latent method factor approach (Podsakoff et al., 2003), and the marker approach of Williams et al. (2010). Overall, the results suggest that CMV does not pose a serious threat to our results.

Non-response bias

To test fort non-response bias, first, we compared construct means for early and late respondents and found no significant difference (Armstrong & Overton, 1977). Second, we compared archival data (i.e., ROS, Return on Assets (ROA), and ROI; firm level data from ORBIS) of our responding managers and the initial sample. Two-sample t-tests revealed no systematic differences in the data between our full sample and the initial sample (ROS: t(5,995) = 1.41, p > .05; ROA: t(5,995) = 1.12, p > .05; ROI: t(5,995) = 1.13, p > .05). These results suggest that non-response bias is not an issue.

Key informant bias

Although we used control items in our survey, we followed three approaches to further strengthen confidence in key informant quality. First, we targeted respondents with a high hierarchical position (Homburg et al., 2012b). As Web Appendix C shows, most key informants (full sample: 66.4%; subsample: 67.1%) were head of department or higher and thus should be knowledgeable about their firms’ capabilities and competitive environments. Second, we checked key informant competency by asking respondents for their job experience (Homburg et al., 2012b), which was, on average, 20.2 years (subsample: 20.5 years). This suggests that informants were well experienced. Third, we calculated inter-rater reliability using the intra-class correlation coefficient for multi-informant cases (n = 67). The average intra-class correlation coefficient for the measures (i.e., loyalty, customer-related coordination costs, switching costs, number of touchpoints, and product vs. service) for the subsample was .61, indicating appropriate consistency among raters according to Cicchetti’s (1994) guidelines and thus suggesting that key informant bias is not a problem.

Discriminant validity

To assess discriminant validity, we ran two checks. First, we used the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which provides support for discriminant validity (see Table 4). Second, we calculated the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations according to Henseler et al. (2015). The results show that the HTMT ratios of all constructs were well below the recommended threshold of .85 (see Web Appendix F). Thus, all measures demonstrate satisfactory discriminant validity.

Multicollinearity

To account for multicollinearity, we calculated variance inflation factors. Factors were well below harmful levels (i.e., between 1.05 and 1.64) (Hair et al., 2019). Consequently, multicollinearity does not seem to threaten the validity of our results.

Results

Main effects

We estimated a structural equation model (SEM) using Stata 17, finding a good overall model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999): χ2/df = 2.44; CFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .05. Table 5 includes the estimates for the model. We find that, as predicted, B2B CJMC has a consistently positive impact on customer loyalty (.58, p < .01) but also increases customer-related coordination costs (.29, p < .01). Thus, H1 and H2 are supported.

Indirect effects

To glean further insights into B2B CJMC’s overall impact, we tested for an indirect effect of B2B CJMC on ROS. For this, we employed a bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 repetitions within 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for our main-effects model (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) (see Table 6). The results reveal that B2B CJMC has a positive indirect effect through customer loyalty (i.e., .13, p < .01, 95% CI [0.57; 1.90]) and a marginally negative effect through customer-related coordination costs (i.e., –.03, p < .10, 95% CI [–0.47; 0.00]) on ROS. These opposing indirect effects suggest that the financial performance benefits from B2B CJMC are mitigated by the customer-related coordination costs that are simultaneously incurred. Indeed, the total indirect effect of B2B CJMC on ROS is slightly reduced but still significantly positive (i.e., .10, p < .01, 95% CI [0.22; 1.58]).

Moderating effects

Using SEM, we tested our moderating hypotheses by estimating latent interaction terms (Marsh et al., 2004, 2013a, b).

Applying this approach, we built three latent interaction terms to measure our moderation: (1) B2B CJMC × switching costs, (2) B2B CJMC × number of touchpoints, and (3) B2B CJMC × product versus service. The interaction-effects model (see Table 5) has a good overall fit: χ2/df = 2.00; CFI = .93; TLI = .92; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .06. The results confirm that high customer switching costs strengthen the positive effect of B2B CJMC on customer loyalty (.14, p < .01), in support of H3a. However, we do not find a moderating effect of switching costs on the effect of B2B CJMC on customer-related coordination costs (.03, p > .05); thus, H3b is rejected. Furthermore, we find that a high number of touchpoints strengthens the positive effect of B2B CJMC on both customer loyalty (.10, p < .05) and customer-related coordination costs (.11, p < .05), in support of H4a and H4b. Finally, the results confirm that a stronger product focus than service focus weakens the positive effect of B2B CJMC on both customer loyalty (–.12, p < .01) and customer-related coordination costs (–.14, p < .05), in support of H5a and H5b.

Simple-slope analyses

To glean further insights, we examined the simple slopes (marginal effects) of B2B CJMC across different levels of our moderators (see Fig. 2). More precisely, for our moderators switching costs and number of touchpoints, we used three levels: one standard deviation below the mean (–1σ), at the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean (+ 1σ) (Cohen et al., 2002). For our moderator product versus service, we used a dummy to classify SBUs as operating primarily in either product or service businesses. We calculated the first partial derivative of the two dependent variables (DepVar)—customer loyalty (CL) and customer-related coordination costs (CrCC)—on B2B CJMC over one of the respective moderators (Mod)—that is, switching costs (SC), number of touchpoints (NoT), or product versus service. To calculate the slopes, we used the unstandardized coefficients and the mean-centered data (Preacher et al., 2006). The generalized equation is:

First, regarding the slopes contingent on switching costs, the results reveal that for SC = high and SC = low, B2B CJMC has a positive effect on CL (\(\partial\mathrm{CL}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+1\mathrm\sigma}=.90\), p < .01; \(\partial\mathrm{CL}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+1\mathrm\sigma}=.56\), p < .01) and CrCC (\(\partial\mathrm{CrCC}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+1\mathrm\sigma}=.57\), p < .01; \(\partial\mathrm{CrCC}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+1\mathrm\sigma}=.35\), p < .01). Second, regarding the slopes contingent on number of touchpoints, while for NoT = high and NoT = low B2B CJMC has a positive effect on CL (\(\partial\mathrm{CL}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+1\mathrm\sigma}=.81\), p < .01; \(\partial\mathrm{CL}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+1\mathrm\sigma}=.55\), p < .01), B2B CJMC has a non-significant effect on CrCC for NoT = high and a positive effect on CrCC for NoT = low (\(\partial\mathrm{CrCC}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+1\mathrm\sigma}=.62\), p > .05; \(\partial\mathrm{CrCC}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+1\sigma}=.28\), p < .01). Third, regarding the slopes contingent on product versus service, B2B CJMC has a positive effect on CL (\(\partial\mathrm{CL}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+\mathrm{product}}=1.06\), p < .01; \(\partial\mathrm{CL}/\partial{\mathrm{CJMC}}_{+\mathrm{service}}=.68\), p < .01) and CrCC (\(\partial\mathrm{CL}/\partial{\mathrm{CrCC}}_{+\mathrm{product}}=.57\), p < .01; \(\partial\mathrm{CL}/\partial{\mathrm{CrCC}}_{+\mathrm{service}}=.38\), p < .01) under both a product and service focus.

Control effects

The effects of control variables reflect prior expectations and results. For example, a buyer’s power is significantly, positively related to a supplier’s coordination costs (Grewal et al., 2015). The same accounts for technological change (Ahearne et al., 2022). Furthermore, a customer’s switching costs positively affect customer loyalty (Lam et al., 2004). In addition, the number of touchpoints is positively associated with customer loyalty but also customer-related coordination costs (Herhausen et al., 2019). Finally, we find that a product (vs. service) focus is positively related to customer loyalty.

Post hoc analyses

Test for complementarities among the B2B CJMC dimensions

To empirically test that B2B CJMC is a second-order reflective construct that derives its success from the complementarities among its first-order dimensions, we use the latent variable approach. Accordingly, we estimate two SEMs to test B2B CJMC’s effects: (1) a complementarity-effects model and (2) a direct-effects model. The first model specifies B2B CJMC as a second-order construct and thus captures “the complementarity of the first-order factors by accounting for their multilateral interactions and covariance” (Tanriverdi & Venkatraman, 2005, p. 111). The second model, by contrast, specifies B2B CJMC as a four-factor construct that includes only “the first-order factors and models their pair-wise covariance” (Tanriverdi & Venkatraman, 2005, p. 114). To comprehensively evaluate B2B CJMC’s effects, we investigate the two direct effects in our main-effects model.

The results from the complementarity-effects model reveal that the structural links are positive and significant (p < .01). By contrast, the results from the direct-effects model show that only two of eight structural links are positively significant (p < .05).Footnote 7 Taken together, these results show the superiority of the complementarity-effects model to the direct-effects model in terms of (1) hypothesized effects and (2) model parsimony. Thus, we find strong empirical support for conceptualizing B2B CJMC as a second-order reflective construct.

To further underpin our conceptual assumption of complementarity and to deepen understanding, we also calculated the interaction effects among the four B2B CJMC dimensions. The examination of interaction effects in the context of complementarity seems reasonable because a set of resources is complementary “when doing more of any one of them increases the returns to doing more of the others” (Tanriverdi & Venkatraman, 2005, p. 100)—that is, there are interactions. As Web Appendix G reveals, the four dimensions have strong interaction effects. For example, the dimensions of value anchoring and individual control are of particular importance in increasing the effectiveness of B2B CJMC—i.e., they increase/decrease the effects of other dimensions. Nevertheless, despite these interaction effects, “[t]he returns obtained from the joint adoption of complementary resources are greater than the sum of returns obtained from the adoption of individual resources in isolation” (Tanriverdi & Venkatraman, 2005, p. 100), as demonstrated by our latent variable approach.

Short scale

To simplify the use of the B2B CJMC construct for future research and also lend itself to marketing practice, we aimed to develop a more parsimonious scale (see Table 7). Therefore, we selected five items that best represented the conceptual definition of all four B2B CJMC dimensions for statistical reasons within a single latent model (i.e., highest FLs within a single latent construct). We ran (1) a CFA using our full sample to assess the scale’s reliability and validity and (2) our main-effects model using the developed scale. The results confirmed the applicability of the short scale in terms of goodness-of-fit indices and effect sizes. Nevertheless, the long scale shows lower AIC and BIC values (short vs. long scale: ΔAIC = 2,341; ΔBIC = 2,353) (see Web Appendix H), indicating the superiority of the long scale.

Discussion

Theoretical contributions

Although scholars have highlighted the role of capabilities in holistically managing touchpoints in B2B CJs, they have paid little attention to this research inquiry. We fill this gap by providing a theoretically sound and managerially relevant conceptualization of a supplier’s capability that creates, implements, and monitors customer value in B2B CJs—that is, B2B CJMC. Drawing on in-depth interviews and a cross-industry dataset, this investigation conceptualizes and operationalizes B2B CJMC as a second-order construct that manifests itself in four first-order dimensions. Thus, we provide meaningful measurement instruments beyond a consumer or branding context (Kuehnl et al., 2019) and consequently respond to the need to take a broader perspective on the management of touchpoints (see Table 1).

Theoretically, unlike the majority of B2B studies that use the dynamic capabilities lens, we argue why B2B CJMC is a dynamic capability by applying four criteria originating from Eisenhardt and Martin’s (2000) study. Specifically, by applying the criteria of complementarities, we show that B2B CJMC derives its success from all four dimensions simultaneously. In this way, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to take a systematic approach to examine the dynamic capabilities approach in the context of related literature. Consequently, our results empirically indicate that CJMC not only in a B2C but also in a B2B context is a unique construct in its own right that warrants greater research attention. As such, our proposed short scale might be a fruitful standard to stimulate and drive further investigations in this research area.

Moreover, we provide a strong and nuanced understanding of value creation through B2B CJMC by relying on primary and secondary data. Importantly, we find that B2B CJMC directly increases customer loyalty (H1) and customer-related coordination costs (H2) and also indirectly affects a supplier’s performance through these two opposing mechanisms. Accordingly, we show that B2B CJMC significantly affects firm and customer performance metrics that marketing executives use and are held accountable for (Katsikeas et al., 2016), thus emphasizing the marketing relevance of B2B CJMC. Moreover, whereas most of the literature on dynamic capabilities and CJM proposes universally positive outcomes (see Table 1), we also uncover a cost-related dark side. To advance dynamic capabilities and CJM theorizing, we encourage scholars also to examine more negative consequences.