Abstract

Retail has responded to the continuing shift in consumer preferences toward ephemerality and immediacy with the development of temporary experiential stores known as pop-ups. In the realm of experiential stores, research has identified retail and brand experience as affecting positive word of mouth (WoM). Surprisingly, however, studies have yet to consider pop-ups’ distinguishing feature of ephemerality or their main type of visitor, consumers with a high need for uniqueness (NFU). Building on five studies (two field studies, three experiments) and contributing to scarcity research, our results demonstrate the positive effect of an experiential store’s temporal scarcity for consumers and brands–namely, an enhanced brand experience. Moreover, our research corroborates our prediction of self-enhancement: For high-NFU consumers, brand experience translates into increased positive WoM when communicating with distant others. In contrast, when communicating with close others, the instinct of high-NFU customers to preserve their uniqueness does not affect positive WoM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Retailing faces the constant challenge of an increasing share of shopping being conducted digitally rather than in person. As a result, consumers have access to an array of information and alternatives that is wider and more diverse than ever before (Kozinets et al., 2002). In this competitive environment, it is no longer sufficient for brick-and-mortar retailers to differentiate themselves from the competition by offering attractive prices or innovative products (Grewal et al., 2009); because the satisfaction of functional demands is now taken for granted, intangible components have become more important. As experience has the potential to be more valuable to consumers than the physical product or service itself (Kotler, 1973; Pine & Gilmore, 1998), brick-and-mortar retailing has been adapting to this trend and attempting to satisfy consumers demanding memorable in-store experiences (Verhoef et al., 2009). Such experiential stores are operated by manufacturers themselves under a single brand name and with the primary goal of strengthening the brand (Kozinets et al., 2002). For example, flagship stores are a type of experiential store characterized by their unique store design. Complementary to traditional brand stores, flagships offer a novel product and brand staging. Their main goal is not to push sales or profit metrics in the stores themselves (Jahn et al., 2018) but rather–like all experiential stores–to tell a story and entertain the customer (Kozinets et al., 2002) to ultimately strengthen brand loyalty and brand image (Hollenbeck et al., 2008).

In addition to the increased experience orientation, today’s consumer behavior is characterized by a desire for ephemerality and liquid consumption that is encouraged by digitalization and social acceleration (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2017; Rosa, 2010). Nowadays, consumers are no longer wary of brands that embody adaptability, flexibility, and mobility (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2017) but rather value them for offering limited editions or an exclusive distribution outlet (Aggarwal et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2012).

Considering the greater emphasis on experiences and the modern consumer’s preference for ephemeral consumption (Robertson et al., 2018), many companies have taken to launching temporary experiential stores known as pop-ups. As a special type of experiential store, pop-ups encourage consumers to experience the brand in a more accessible way due to their ephemeral nature. Temporary retail establishments have a long history and are applied in a variety of contexts and forms. These forms can be categorized according to their objectives as communicational, experiential, testing, or transactional (Warnaby et al., 2015). Building on established literature (e.g., Klein et al., 2016; Robertson et al., 2018), this work defines pop-ups as temporary retail environments that promote a single brand and are operated to deliver experiences. As with all experiential stores, the purpose of temporary experiential stores is not revenue generation (Klein et al., 2016); instead, they are primarily designed to create brand awareness, test new products or foreign markets, or bolster long-term customer relationships (de Lassus & Freire 2014; Klein et al., 2016). The positive word of mouth (WoM) that experiential stores generate due to emotional arousal contributes to these goals by helping cement the brand in consumers’ minds. Some even consider the creation of positive WoM to be a logical requirement for the effectiveness of ephemeral stores (Robertson et al., 2018).

Research on experiential stores has identified the retail experience–visitors’ overall perceptions of a store’s characteristics (Verhoef et al., 2009)–as having an impact on consumer behavior, especially in terms of producing positive WoM for the brand (Jahn et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2016). This relationship has in turn been shown to be mediated by brand experience (Jahn et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2016; Nierobisch et al., 2017): consumer responses to brand-related stimuli, whether subjective, internal responses (sensory, affective, and intellectual) or behavioral ones (Brakus et al., 2009). Still, there are various types of experiential stores with distinct attributes. As these characteristics may have differing effects on consumer behavior, it seems crucial for the development of design recommendations that brands operating experiential stores understand these effects.

Besides their design novelty and locational surprise value (with, e.g., minimalist spaces), one of the most important features distinguishing pop-ups from other experiential stores is their ephemerality (de Lassus & Freire 2014; Robertson et al., 2018). This characteristic may contribute to consumers’ brand experience and thus their intentions to spread positive WoM. Brands launching pop-ups exploit this aspect of impermanence to inspire excitement for the store and the brand (de Lassus & Freire 2014; Henkel & Toporowski, 2021; Henkel et al., 2022; Zogaj et al., 2019), with the limited availability used in line with commodity theory (Brock, 1968) to increase the brand’s perceived value and potentially also induce arousal (Zhu & Ratner, 2015). These effects led Robertson et al. (2018) to highlight a need to investigate the ephemeral and experiential qualities of pop-ups in detail. As scarcity may increase a brand’s perceived uniqueness and value, it is conceivable that an experiential store’s temporal scarcity could affect the link between retail and brand experience, thus further heightening positive WoM for the brand. Considering the relevance of ephemerality for consumer behavior, it is surprising that research on experiential stores–pop-ups in particular–has largely focused on the sole influence of the in-store experience on WoM (e.g., Klein et al., 2016).

Recognizing the need to focus on experiential stores with a particular characteristic (i.e., ephemerality), we must then address the question as to what type of customers such stores attract. As experiential stores are highly original and unique, they are expected to be particularly attractive to those who use consumption to distinguish themselves from others: consumers with a high need for uniqueness (NFU) (Henkel & Toporowski, 2021; Robertson et al., 2018). However, research on NFU and WoM has found consumers with a high (versus low) NFU to be less willing to generate positive WoM out of fear of losing their uniqueness (Cheema & Kaikati, 2010). If this is indeed the case, experiential stores’ main group of visitors would be acting contrary to their goals by spreading WoM.

From WoM research, we know that people are likely to adjust their WoM behavior according to their audience. Studies have also shown that recommendations from close others are perceived to be more authentic and trustworthy than those from distant others (Moldovan et al., 2015). This means that the impact of WoM depends on both the sender and receiver. Accordingly, it is important for brands and their profit generation to know whether the tendency for those with a high NFU to reduce WoM applies both when speaking with close others (e.g., friends) and when the audience comprises distant others (e.g., the public). While interpersonal WoM involves face-to-face communication, typically between close relations (Sun et al., 2006), publicly spread electronic word of mouth (eWoM) is imparted to distant others and a multitude of people and institutions via the internet (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). The low interpersonal closeness involved when communicating with strangers or the public (e.g., in an online context) may motivate high-NFU consumers to self-enhance and communicate positive information (Dubois et al., 2016), which is beneficial for brands. However, the same consumers may try to preserve their uniqueness by withholding information to prevent close friends from enjoying the same experiences with the brand (Cheema & Kaikati, 2010; Moldovan et al., 2015). If these contrary behaviors indeed hold true, experiential stores need to align their goals–the creation of WoM–with their main group of visitors–high-NFU consumers. Operators of experiential stores might face the challenge of determining whether and how they could allay high-NFU consumers’ fears of losing their uniqueness. At the same time, they might reconsider what type of visitors they target and instead aim to attract low-NFU consumers, who tend to spread interpersonal WoM as opposed to eWoM. Therefore, we propose a need to analyze the impact of brand experience on positive WoM by considering consumers’ NFU and differentiating between the two types of WoM audiences (close friends vs. distant others).

The purpose of this work is threefold. First, as scarcity may increase a brand’s perceived uniqueness and value, we aim to demonstrate the effect of store ephemerality on the link between retail experience and brand experience. This contributes to the current literature stream finding that marketing strategies using limited availability create scarcity and further a desire for the scarce product or brand (Brock, 1968; Hamilton et al., 2019; Lynn, 1991). Furthermore, we add to the existing literature on experiential stores, which has tended to ignore one of pop-ups’ main distinguishing features (e.g., Klein et al., 2016). Second, we seek to understand the role of NFU in the relation between brand experience and positive WoM. Research regarding experiential stores has generally overlooked one of the format’s main visitor groups–consumers with a high NFU–although the specific traits of its members may play a game-changing role in the success of such stores. Third, we intend to verify the value of a more detailed view of the effect of NFU on WoM, suggesting a need to differentiate between WoM among close friends (interpersonal WoM) and WoM among distant others (eWoM). To achieve these aims, we conducted five studies that examine the roles of store ephemerality and NFU in the relationship between retail experience, brand experience, and positive WoM. Our findings offer valuable insights into the process of promoting positive WoM through crucial features of experiential stores. In doing so, they contribute to the communicational objectives of experiential stores and provide important implications for brands regarding the development of successful store concepts. Armed with this knowledge, it is conceivable that brands might choose to highlight store ephemerality by implementing elements such as a special interior design, performative aspects, or a non-conventional location. Furthermore, they may see it fit to consider expanding their target visitor groups when launching experiential stores. For example, brands may target high-NFU visitors and thus promote eWoM with a unique and distinctive store design or limited edition products and also attract low-NFU visitors to foster interpersonal WoM.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Before discussing the specifics of our studies, we begin by introducing the concept of experiential stores–particularly pop-ups as proxy for ephemeral experiential stores–and briefly reviewing the state of the art in research. We then provide a theoretical background on the effects of store ephemerality and NFU in the relationship between retail experience, brand experience, and positive WoM. Along the way, we introduce our hypotheses.

Retail experience, brand experience, and positive word of mouth

Experiential stores aim to offer an unforgettable retail experience, delivered through the store’s uniqueness, atmosphere, hedonic shopping value, exclusive product assortment, and staff service quality. The store’s uniqueness is represented, for example, in an up-to-date, special store design that surprises and excites visitors (Robertson et al., 2018). The novel store design, location, and other store attributes affect emotions and identification, thus distinguishing experiential stores from conventional ones and making them unique (Klein et al., 2016). In addition to their uniqueness, experiential stores offer an inviting and interactive atmosphere that is perceived as attractive and pleasant (Klein et al., 2016). Their hedonic shopping value is created by providing entertainment and fun during the store visit (Klein et al., 2016). With live music, games, and interactive touchpoints, the stores provide an experiential environment for visitors (Zogaj et al., 2019). Offering an exclusive product assortment is another opportunity to heighten the visitors’ retail experience, although experiential stores are not focused on sales. For example, Picot-Coupey (2014) found experiential stores to offer a narrow-ranged merchandise mix, focusing on only one product line. The products sold in such stores may be new, limited editions, or both; showcasing limited editions or unique, hard-to-find products also contributes to the store’s uniqueness (Robertson et al., 2018). Another major factor of retail experience is staff service quality, especially a personal conversation between customer and brand. In experiential stores, sales representatives may not only inform customers but also enter into personal exchanges with them (Kim et al., 2010; Niehm et al., 2006).

As retail experience touchpoints are often related to the brand, with brand-tailored information, brand representatives, and corporate design, a favorable retail experience in experiential stores can translate to a superior brand experience (Jahn et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2016). This enhanced brand experience plays an important role in effecting positive brand-related behavior (Brakus et al., 2009; Verhoef et al., 2009). Brand experience can be understood as a consumer’s subjective internal responses (sensations, feelings, cognitions) and behavioral reactions to brand-related stimuli (Brakus et al., 2009). Although recent research provides evidence for the effect of retail on brand experience (Klein et al., 2016), the creation of brand experience may also depend on pre-existing brand experience (Brakus et al., 2009; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Jahn et al., 2018) provided evidence that retail experience within experiential stores updates brand experience, although the impact is smaller than previously assumed (e.g., Dolbec & Chebat 2013; Nierobisch et al., 2017).

Further research has acknowledged the role of experiential stores in achieving brand’s communication goals by identifying retail and brand experience as important drivers of positive WoM and long-term brand outcomes (Jahn et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2016; Robertson et al., 2018). WoM generation is of particular interest to researchers because it is considered a logical requirement for the effectiveness of experiential stores. In this context, researchers have demonstrated that positive WoM is spread more often than negative WoM (Berger & Milkman, 2012; East et al., 2007). As consumers prefer to share interesting, unique, and entertaining content (Berger, 2014), especially after experiencing emotional arousal in response to a brand encounter (brand experience; Lovett et al., 2013), research suggests that a retail experience entailing the perception of experiential stores as having such desired qualities stimulates brand experience and thus further positive WoM toward the brand (Jahn et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2016; Nierobisch et al., 2017).

The moderating role of experiential stores’ ephemerality

The relatively new phenomenon of experiential stores in the form of pop-ups raises the question of what role ephemerality plays in the experiential store concept. It may have the potential to strengthen the impact of experiential stores’ typical characteristics, especially when analyzing their effects on positive WoM (e.g., Jahn et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2016; Nierobisch et al., 2017).

In contrast to the permanence of other experiential stores, pop-ups are usually only open for a couple of weeks (Klein et al., 2016). Their temporal scarcity is often reflected in elements such as the store’s interior design, event-like character, and communication strategy (Shi et al., 2019), while displays counting down the time until the store’s permanent close may make their ephemerality explicit (Surchi, 2011). There are also special design characteristics that may differentiate temporary from other experiential stores: Such stores are aesthetic and utilize unique imagery to exude novelty. They are also often found in non-traditional locations or minimalist spaces (de Lassus & Freire, 2014; Robertson et al., 2018). Though present in other experiential stores, these features of retail experience are on an elevated level in temporary ones.

Temporary experiential stores are implemented in a variety of contexts with diverse objectives that can be categorized as experiential, communicational, testing, or transactional (Warnaby et al., 2015). First popularized in 2004 by the Japanese luxury label Commes des Garçons, which briefly occupied a former bookstore in Berlin, temporary experiential stores have become a thriving retail format used widely across various sectors, including fashion, FMCG, automotive, and IT. Even pure online and direct-to-consumer retailers are launching pop-ups at a growing rate. Building on established literature (Klein et al., 2016; Robertson et al., 2018), this study focuses on pop-ups as temporary retail environments that promote a single brand and are operated to deliver an experience. However, the impact of a pop-up store goes beyond the immediate in-store effect; pop-ups have inherent communicational objectives, as they aim to create WoM. We focus on this aspect, acknowledging that some pop-ups are also launched to test foreign markets or new products. Furthermore, although flash retailing and seasonal stores, such as Halloween stores, do exist only for a limited amount of time, they pursue transactional objectives; as they are thus neither experience nor WoM oriented, they fall outside the scope of our study.

By satisfying consumers’ desire for liquid consumption (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2017), the temporary nature of pop-ups relates to an essential precondition of economic behavior: scarcity (Lynn, 1991). Scarcity can relate to either time, as pop-ups do, or quantity (Aggarwal et al., 2011; Parker & Lehman 2011). According to commodity theory (Brock, 1968), possessing something of limited availability evokes feelings of personal distinctiveness. Consumers therefore have a greater desire for scarce goods and services and regard them as more valuable (Lynn, 1991). Although a limited availability may also have negative consequences, such as competitive threats from other consumers (Kristofferson et al., 2017), several positive effects for customers and brands stand out. Aggarwal et al. (2011) demonstrated that a message indicating a product’s limited time availability has a positive effect on consumer behavior in terms of purchase intention. Furthermore, time scarcity is likely to affect choices when consumers lack strong prior preferences (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). At the same time, scarcity increases perceptions of quality and value (Suri et al., 2007). Time limitation even has the potential to generate positive long-term consequences (Hamilton et al., 2019). Along similar lines, Balachander & Stock (2009) showed that offering limited editions as an expression of quantitative scarcity has a positive direct effect on brand profits through increased willingness to pay. Wu et al. (2012) found that increasing perceived scarcity might boost perceived uniqueness, which is useful for our study. Zhu and Ratner (2015) explained all of these positive effects to be results of heightened arousal as induced by scarcity.

Given the relevance of ephemerality for consumer behavior, it is surprising that research on temporary experiential stores has largely analyzed retail and brand experience as determinants of positive WoM without highlighting the role of temporal scarcity (Klein et al., 2016). Indeed, the temporal experiential store’s distinguishing feature–ephemerality–may also contribute to consumer behavior within such stores: Temporal scarcity has been found not only to attract visitors (Henkel & Toporowski, 2021), increase their willingness to pay (Zogaj et al., 2019), and affect their intention to purchase standard and exclusive products in the store (Henkel et al., 2022) but also to arouse excitement for the store and brand (de Lassus & Freire 2014).

In light of these findings, we consider whether taking ephemerality into account may provide further insights into the relationship between retail and brand experience. Indeed, the impact of retail experience on brand experience has been shown to depend on store type, with the effect being greater for flagship stores than for non-experiential brand stores (Jahn et al., 2018). Hence, an experiential store’s limited existence may strengthen a consumer’s perception of the store (retail experience), generate arousal, and thus further reinforce the consumer’s brand experience. We therefore predict that the link between retail and brand experience is further qualified by (perceived) store ephemerality.

H1

The positive effect of retail experience on brand experience increases if (perceived) store ephemerality is high.

The moderating role of need for uniqueness

Experiential store research has granted a great deal of attention to consumer characteristics (Kim et al., 2010; Niehm et al., 2006; Robertson et al., 2018). As experiential stores offer a highly original and unique retail environment, they are expected to attract consumers with a high NFU (Henkel & Toporowski, 2021; Robertson et al., 2018). Such individuals engage in consumer counter-conformity behaviors by making choices that are creative, unpopular, or reflect an avoidance of similarity to others (Tian & McKenzie, 2001).

Research on experiential stores has paid no particular attention to this main group of visitors, which is perhaps due to the dominance of qualitative studies (e.g., de Lassus & Freire, 2014; Lowe et al., 2018; Overdiek & Warnaby 2020). However, NFU could play a significant role in the effects of experience on positive WoM. Accordingly, Robertson et al. (2018) proposed that future research should examine whether WoM decreases with greater NFU in experiential store contexts.

Uniqueness theory proposes that individuals seek unique identities (Snyder & Fromkin, 1977). To satisfy their need for uniqueness and to develop and maintain their self-esteem, high-NFU consumers are motivated to adopt self-distinguishing behaviors that differentiate them from others, especially those within their social groups (Simonson & Nowlis, 2000; Snyder, 1992; Tian & McKenzie, 2001). Therefore, they prefer to shop at non-mainstream stores or consume exclusive, scarce, and customized brands (Burns & Warren, 1995; Franke & Schreier, 2008). In line with social comparison theory, high-NFU consumers value special, unusual hotel stays (Ames & Iyengar, 2005) and the experience of lucky incidents (Wang et al., 2021). Furthermore, they favor experiences unavailable to others (Fromkin, 1970). Out of fear of losing their uniqueness, such individuals are less willing than those with a low NFU to generate positive WoM for products or brands that they consume (Cheema & Kaikati, 2010).

However, we question whether this assumption is applicable to both WoM shared with close friends and that shared with distant others. Because eWoM typically takes place between strangers (often several at once) and interpersonal WoM is mainly used in private conversations among people known to one another (Bickart & Schindler, 2001; Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004; Hoffman & Novak, 1996), in the following we equate eWoM with WoM among distant others and interpersonal WoM with WoM among close friends.

Depending on their audience, people have different communication goals; they are likely to adjust WoM accordingly. When communicating with those who are close, the tendency is to attempt to maintain existing roles and behaviors (Chen, 2017). Hence, we expect that high-NFU consumers want to preserve their uniqueness and prevent close others from enjoying the same experiences with the brand. Moldovan et al. (2015) found that consumers with a high NFU try to scare closer persons out of adopting the same products or brands as they adopted. In contrast, when communicating with strangers or the public, people are likely to try to impress (Chen, 2017); low interpersonal closeness may activate the motive to self-enhance and communicate positive information (Dubois et al., 2016). This is in accordance with Lovett et al. (2013), who demonstrated that individuals manifesting high NFU spread interpersonal WoM much less than eWoM. The explanation for this could be twofold: Because personal interactions offer more options for people to express their uniqueness (e.g., through their visual appearance), spreading WoM is less necessary. At the same time, as communication on online platforms is usually broadcasted among strangers, people may feel a greater need to prove their uniqueness through eWoM. In addition, Barasch and Berger (2014) found that communicating with multiple people leads consumers to share content that makes them look good. In line with Cheema and Kaikati (2010) and Robertson et al. (2018), we assume the effect of brand experience on positive interpersonal WoM to decrease if a consumer’s NFU is high. Conversely, we expect that high-NFU consumers may seek to flaunt their uniqueness through communication with distant others; NFU thus reinforces the effect of brand experience on positive eWoM.

H2a

The positive effect of brand experience on positive interpersonal WoM about the brand decreases if NFU increases

H2b

The positive effect of brand experience on positive eWoM about the brand increases if NFU increases.

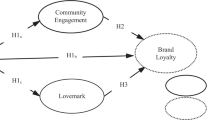

Overview of studies

Our research set out to examine the relationship between retail experience, brand experience, and positive WoM by considering the moderating roles of (perceived) store ephemerality and NFU. Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual framework. We tested our hypotheses in five studies: two field studies and three experiments. These studies present a mix of approaches and samples that provide converging evidence for the need to consider store ephemerality and NFU as moderators in the mechanism linking retail experience with brand experience and WoM.

First, we conducted a field study involving real consumer behavior within a temporary experiential store context. We demonstrated in Study 1 that only if consumers perceive the store to be ephemeral does retail experience enhance brand experience, which in turn further heightens positive WoM. This finding that the link between retail and brand experience depends on perceived store ephemerality is consistent with H1. In Study 2 we verified the robustness of this moderating effect by conducting another field study considering a different brand and product category. In addition, the results offer evidence for the proposed need to differentiate between the two types of WoM audiences (close friends = interpersonal WoM vs. distant others = eWoM) when integrating NFU into the model. Supporting H2a and H2b, the results of Study 2 show that an increase in NFU decreases the positive effect of brand experience on interpersonal WoM but increases the effect for eWoM. In an experiment within Study 3, we manipulated consumers’ NFU as high or low and employed a one-factor, two-level (NFU: low vs. high NFU) between-subjects design. The findings provide additional support for our hypotheses. Study 4 was conducted to further verify our model by applying it to a typical experiential store product category, namely fashion. Within this experiment, we manipulated store ephemerality by employing a one-factor, two-level (store ephemerality: flagship vs. pop-up store) between-subjects design. Although the results support H1 and H2b, they surprisingly show no significant interaction of brand experience and NFU for interpersonal WoM; thus, we found no support for H2a. In Study 5, we used the same fashion context as in Study 4 and employed a 2 (store ephemerality: flagship vs. pop-up store) × 2 (NFU: low vs. high NFU) between-subjects design. Again, we could confirm H1 and H2b but still had no confirmation for H2a in the fashion category. Across these five studies, we find support for our theorizing regarding the role of (perceived) store ephemerality and NFU in experiential stores.

Study 1

Method

A national brand in the fittings and sanitary ware category that sells its products primarily through construction stores and other retailers agreed to let us approach its pop-up store visitors for the purpose of this field study. In December 2019 the brand’s pop-up truck was located in one of the largest cities in Germany. Transformed into a modern, mobile showroom, the pop-up’s augmented brand display contained a video wall informing consumers about the quality and manufacturing process of the brand’s products. Furthermore, it included an array of innovative products representing the future of water design–fittings, showers, ceramic fixtures, toilets, and state-of-the-art systems for water safety–all of which could be touched, tested, and experienced. The architectural and interior design was tailored to the brand, with its colors present throughout the store.

During one day, 48 pop-up store visitors we approached upon exiting agreed to participate in our study (Mage = 39.06, SD = 15.41; 37.5% female; 12.5% students). To avoid picking up cultural influences as a moderator for the perception of the pop-up, we invited only German visitors to take part. For all items we used 7-point Likert scales (see Appendix 1 for all construct measures).

First, the participants evaluated their retail experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.76). We measured participants’ perceptions of extraordinary store atmosphere, staff service quality, entertainment, uniqueness, and product assortment in five items based on Jahn et al. (2018) and Klein et al. (2016). Next, they were asked to indicate perceived store ephemerality. Here, we used a single item adapted from Eisend (2008). Afterward, respondents assessed their brand experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.82), measured with four items relating to sensual, affective, intellectual, and behavioral components based on Brakus et al. (2009). We then measured participants’ intentions to spread positive WoM, both interpersonally (two items; Maxham & Netemeyer, 2002) and electronically (two items; Okazaki et al., 2014), and computed a WoM index as an average of these four items (Cronbach’s α = 0.75). Finally, all respondents were asked to specify their product involvement (Mittal & Lee, 1989; Cronbach’s α = 0.88). We used this measure further as a covariate, as products in the fittings and sanitary ware category are costly and tend to require conscious purchase decisions.

Results

To examine the moderating role of perceived store ephemerality in the relationship between retail experience, brand experience, and WoM, we performed a moderated mediation (using PROCESS Model 7 with 10,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes 2018). Our findings are summarized in Table 1 (Study 1).

The results reveal that a better retail experience significantly improves brand experience (b = 0.58; p = .008). Following H1, the influence of retail experience on brand experience is assumed to be stronger if consumers perceive the store’s availability to be limited; indeed, a significant interaction confirms that this relationship is affected by perceived store ephemerality (b = 0.32; p = .005). As a spotlight analysis reveals, retail experience only affects one’s brand experience when perceived store ephemerality is high (b = 1.16; p < .001) and not when it is low (b = 0.19; p = .528). These results offer support for H1 and are depicted in Fig. 2 (Study 1). In addition, consumers’ product involvement may be a further impact factor for brand experience (b = 0.29; p = .030).

Looking at the impact on WoM, we found that both retail (b = 0.59; p = .023) and brand experience (b = 0.31; p = .074) affect consumers’ intentions to spread WoM directly (see Table 2, Study 1). Moreover, the results reveal that the indirect effect of retail experience through brand experience on WoM depends on perceived store ephemerality (index of moderated mediation: 0.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.009, 0.232). Brand experience mediates the effect of retail experience on WoM when perceived store ephemerality is high (indirect effect: 0.36; 95% CI = 0.053, 0.709) but not when it is low (indirect effect: 0.06; 95% CI = − 0.131, 0.255). A further explanation for WoM may be provided by the significant effect of the covariate product involvement (b = 0.26; p = .077).

Discussion

Assessing real consumer behavior in a temporary experiential store context, Study 1 provides evidence that only if consumers perceive the store to be less temporally available does retail experience increase brand experience. In turn, brand experience further heightens positive WoM for the brand. This finding that the link between retail experience and brand experience is dependent on perceived store ephemerality is consistent with commodity theory and supports H1. In doing so, it contributes to experiential store research, which has already identified a significant link between retail and brand experience but has not considered one of pop-ups’ differentiating features in this relationship (Klein et al., 2016). In line with scarcity research, the results underline the important impact of time limitations on consumer behavior.

Study 2

Method

The primary goal of Study 2 was to investigate the role of NFU in the relationship between brand experience and WoM. Additionally, it sought to provide further support for the relationships explored in the previous study.

This field study was conducted with a German bike manufacturer that operates internationally and sells its products largely online and via selected retailers. To foster brand awareness, the company decided to open a pop-up store for one week in November 2020 in a large German city. The pop-up displayed brand information through interactive video walls allowing consumers to gather knowledge about the manufacturing processes and brand history. In addition to the standard bikes sold through retailers, the store carried other variations and exclusive product lines. Furthermore, it offered bike customization and product individualization.

Visitors leaving the pop-up store were selected randomly, with 119 respondents ultimately taking part (Mage = 32.04, SD = 10.63; 37.8% female; 9.2% students). To avoid language barriers, only German visitors were recruited. First, participants evaluated their familiarity with the bike manufacturer, measured with a single item in line with Milberg et al. (2010) on a 7-point Likert scale. We used this brand familiarity further as a covariate, as research not only finds consumers with a close brand relation to experience the brand more strongly in experiential stores (Jahn et al., 2018) but also shows positive as well as negative effects of brand familiarity on WoM (Klein et al., 2016). As in the previous study, respondents were asked to indicate their retail experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.80), perceived store ephemerality, and brand experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.84). Furthermore, they specified their intentions to spread positive WoM interpersonally (two items based on Maxham & Netemeyer, 2002; Cronbach’s α = 0.88) and electronically (two items based on Okazaki et al., 2014; Cronbach’s α = 0.80). Finally, all participants were asked to evaluate their NFU (using three items from Tian & McKenzie 2001; Cronbach’s α = 0.66).

Results

To examine in detail how retail experience is linked to WoM through brand experience, considering perceived store ephemerality and NFU as moderators, we performed moderated mediations (using PROCESS Model 21 with 10,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes, 2018). In H1, we predicted that perceived store ephemerality would moderate the effect of retail experience on brand experience. Indeed, the moderated regression analysis results (see Table 1, Study 2) indicate a significant interaction between retail experience and perceived store ephemerality (b = 0.08; p = .071), thus providing further support for H1. A spotlight analysis reveals that retail experience has a stronger effect on brand experience when perceived store ephemerality is high (b = 0.97; p < .001) than when it is low (b = 0.81; p < .001) (see Fig. 2, Study 2).

H2a and H2b predict the necessity of integrating the personality trait NFU into the model and differentiating between interpersonal and eWoM. Specifically, they propose that high NFU enhances the effect of brand experience on eWoM (H2b) but mitigates the effect on interpersonal WoM (H2a). The results of the moderated mediation analyses are outlined in Table 2, Study 2.

For interpersonal WoM, our results indicate that the significant effect of brand experience on interpersonal WoM (b = 0.45; p = .002) is further qualified by a negative interaction with NFU (b = −0.11; p = .091). Analysis of conditional effects shows that brand experience has a stronger impact on interpersonal WoM when NFU is low (b = 0.59; p < .001) than when it is high (b = 0.33; p = .062). These results offer support for H2a and are depicted in Fig. 3 (Study 2). Another explanation for the increase in interpersonal WoM may be offered by brand familiarity (b = 0.28; p < .001).

For eWoM we found different results (see Table 2, Study 2, and Fig. 4, Study 2) indicating a significant positive interaction with NFU (b = 0.18; p = .004). A spotlight analysis reveals that high NFU facilitates the influence of brand experience on eWoM (b = 0.38; p = .006), while low NFU has no effect on this relationship (b = −0.04; p = .774), thus supporting H2b. Furthermore, retail experience (b = 0.36; p = .044) and brand familiarity (b = 0.19; p = .017) also play roles in explaining eWoM.

Discussion

The results of this second field study offer additional support for the moderating effect of perceived store ephemerality on the link between retail and brand experience. Study 2 also provides evidence for H2a and H2b by demonstrating that the effect of brand experience on WoM is affected by NFU. Research regarding experiential stores has generally overlooked the format’s main visitor group of high-NFU consumers. However, our results reveal NFU’s game-changing role in the relation between brand experience and WoM: An increase in NFU decreases the positive effect of brand experience on interpersonal WoM (supporting H2a) and increases the positive effect of brand experience on eWoM (consistent with H2b). Contributing to the findings of Cheema and Kaikati (2010), we see the value of a more detailed view of the effect of NFU on WoM, suggesting a need to differentiate between interpersonal and eWoM when considering NFU in these relationships.

By additionally examining the significant effects of the covariate brand familiarity, we found a positive effect on both interpersonal and eWoM. Thus, we can contribute to recent literature by demonstrating that it is not only new customers who generate WoM (as shown by Klein et al., 2016) but also brand-familiar ones. These customers value the store’s uniqueness and therefore spread positive WoM, spurred by their close brand connection and their interest in acquiring and sharing new brand information (Keller, 1993).

Study 3

Method

For Study 3, we recruited a group of 262 German-speaking participants (Mage = 38, SD = 12.86; 39.3% female; 16% students) through clickworker for a nominal payment and employed a one-factor, two-level (NFU: low vs. high NFU) between-subjects design. For all items we used 7-point Likert scales.

First, to reduce common method bias, we manipulated participants’ NFU to be high or low using an elaboration exercise following Cheema and Kaikati (2010). Those assigned to the high-NFU condition were directed to expound the importance of individualism (being different from others), while participants in the low-NFU condition were asked to elaborate on the value of conformity (being similar to others). For a manipulation check, all participants evaluated their need for uniqueness at the end of the survey (using five items from Tian & McKenzie, 2001; Cronbach’s α = 0.91). As expected, the elaboration task had a significant effect on NFU (Mhigh NFU = 4.64; Mlow NFU = 3.64; p < .001). Therefore, we distinguished between the levels of NFU and coded the high-NFU condition as 1 and the low-NFU condition as 0.

Afterward, participants evaluated their attitudinal and behavioral loyalty to a large national chocolate brand (Cronbach’s α = 0.90), measured with four items based on Liu-Thompkins and Tam (2013) and Yoo and Donthu (2001). We used this brand loyalty further as a covariate. Participants were then asked to imagine entering an experiential store belonging to the chocolate brand and looking around (see Appendix 2 for the description supplied). They were shown photos and videos presenting a variety of products on shelves and informational and interactive attractions within the store. In addition, there was a shop window announcing that the store would only be around for one month. We chose this product category because brands from the FMCG industry are opening experiential stores at an increasing rate–especially pop-ups. Chocolate in particular is a product category that has positive connotations and is accessible to the mainstream; it is gender neutral and inexpensive. We selected this German chocolate brand’s experiential store because it carries additional product variations and exclusive product lines alongside their standard ranges sold through retailers.

Following this scenario, all respondents evaluated their retail experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.91), measured on nine items (Jahn et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2016). They then indicated their perceived store ephemerality, measured with one item based on Eisend (2008), and rated their brand experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.95) across ten items (Brakus et al., 2009). Finally, we measured their intentions to spread WoM electronically (with three items based on Okazaki et al., 2014; Cronbach’s α = 0.92) and interpersonally (with three items based on Maxham & Netemeyer, 2002; Cronbach’s α = 0.92).

Results

To further examine the game-changing roles of store ephemerality and NFU in the relation between retail experience, brand experience, and WoM, we again performed moderated mediations (using PROCESS Model 21 with 10,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes, 2018).

As predicted in H1, the results of the moderated regression analysis (see Table 1, Study 3) indicate that the significant effect of retail experience on brand experience (b = 0.60; p < .001) is further qualified by a significant interaction with perceived store ephemerality (b = 0.16; p = .005). The spotlight analysis reveals that retail experience has a stronger effect on brand experience when perceived store ephemerality is high (b = 0.70; p < .001) than when it is low (b = 0.54; p < .001) (see Fig. 2, Study 3). Preexisting brand loyalty may provide a further explanation for brand experience (b = 0.30; p < .001).

In testing H2a and H2b (see Table 2, Study 3), we again find for interpersonal WoM that the significant effect of brand experience (b = 0.41; p < .001) is further qualified by a negative interaction with NFU (b = −0.22; p = .011). Brand experience has a stronger impact on interpersonal WoM when NFU is low (b = 0.41; p < .001) than when it is high (b = 0.19; p = .011). These results offer support for H2a and are depicted in Fig. 3 (Study 3). Brand loyalty may provide another explanation for the increase in interpersonal WoM (b = 0.33; p < .001). Moreover, the results reveal that the indirect effect of retail experience on WoM through brand experience depends on perceived store ephemerality and NFU (index of moderated mediation: −0.04; 95% CI = − 0.084, − 0.005) (see Table 2, Study 3, for indirect effects).

The results for eWoM are different (see Table 2, Study 3, and Fig. 4, Study 3), indicating a significant positive interaction of brand experience with NFU (b = 0.19; p = .086). The spotlight analysis reveals that high NFU facilitates the influence of brand experience on eWoM more strongly (b = 0.66; p < .001) than low NFU does (b = 0.47; p < .001). In addition, preexisting brand loyalty (b = 0.22; p = .005) may further explain eWoM.

Discussion

The results of Study 3 verify the previous findings by demonstrating within an experiment that perceived store ephemerality and NFU play significant roles in the already established relationship between retail experience, brand experience, and positive WoM. The experiment context allowed us to manipulate NFU to reduce common method bias, yet we still found significant interaction effects.

Study 4

Method

Study 4 set out to verify the results of the previous studies through another experiment, applying the model to a different product category. We selected fashion, the genre that brought temporal experiential stores to the forefront (Niehm et al., 2006). This time, we used social networks and flyers to recruit 160 German participants (Mage = 27.88, SD = 7.81; 63.4% female) and employed a one-factor, two-level (store ephemerality: flagship vs. pop-up store) between-subjects design. For all items we used 7-point Likert scales.

First, participants were asked to evaluate their familiarity with a multinational fashion retailer, measured with a single item in line with Milberg et al. (2010). As in Study 2, we used this brand familiarity further as a covariate. Afterward, participants were given the same scenario as in Study 3, instructing them to imagine visiting one of the retail company’s stores (see Appendix 2). Respondents were randomly assigned to one of two store-type conditions: In the permanent experiential store condition (flagship), participants were presented with photos and videos of a variety of products on shelves as well as of informational and interactive attractions within the store. For the time-restricted condition (pop-up), we added a photo of a shop window announcing that the store would only be around for two weeks. As part of the survey, participants indicated their perceived store ephemerality, measured with one item based on Eisend (2008). The results of a manipulation check indicate that participants perceived the ephemeral experiential store to be significantly less temporally available than the permanent one (Mpop−up = 5.02; Mflagship = 3.66; p < .001). Therefore, we further used this manipulation as a moderator.

Next, we asked participants to fill out the same questionnaire as in Study 3, assessing their retail experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.92), brand experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.94), and intentions to spread WoM both electronically (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) and interpersonally (Cronbach’s α = 0.89). Finally, all participants were asked to evaluate their NFU (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), measured as in Study 3.

Results

To investigate the roles of store ephemerality and NFU in the relationship between retail experience, brand experience, and consumers’ intentions to spread interpersonal and eWoM, we performed moderated mediations as in Studies 2 and 3 (using PROCESS Model 21 with 10,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes, 2018).

In line with our previous studies, the results (see Table 1, Study 4) indicate a significant interaction effect of retail experience and store ephemerality on brand experience (b = 0.39; p = .007). The spotlight analysis reveals a stronger effect of retail experience on brand experience in the pop-up condition (b = 0.84; p < .001) than in the flagship condition (b = 0.45; p = .001). These results provide further support for H1 and are depicted in Fig. 2 (Study 4).

Furthermore, in line with H2a and H2b and given the results of Studies 2 and 3, high NFU would be expected to weaken the effect of brand experience on interpersonal WoM and enhance the effect of brand experience on eWoM. The results of the moderated mediation analyses are summarized in Table 3 (Study 4).

For interpersonal WoM, our results indicate that the significant effect of brand experience (b = 0.50; p < .001) is not mitigated by NFU (b = −0.01; p = .856). Thus, they offer no support for H2a. Though unaffected by NFU, one explanation for the increase in interpersonal WoM may be provided by brand familiarity (b = 0.14; p = .039).

For eWoM, our results replicate those of Studies 2 and 3. The significant direct effect of brand experience on eWoM (b = 0.47; p < .001) is further qualified by a significant interaction with NFU (b = 0.07; p = .081). The spotlight analysis reveals that high NFU has a stronger effect on the influence of brand experience on eWoM (b = 0.58; p < .001) than low NFU does (b = 0.37; p = .001). Thus, H2b is supported (see Fig. 4, Study 4).

Discussion

These results lend further weight to our model by verifying its application for the product category of fashion. With the manipulation of store ephemerality, the results provide additional evidence for the need to include this factor in existing models. Considering that temporal scarcity may be one special characteristic of experiential stores, the finding that retail experience translates into brand experience more easily among limited experiential stores (pop-ups) than permanent ones (flagships) offers support for H1’s proposed positive effect of ephemerality. Furthermore, the experiment highlights the need to differentiate between interpersonal and eWoM when it comes to NFU. Confirming H2b, the results indicate that high NFU has a greater effect than low NFU on the influence of brand experience on eWoM.

Surprisingly, unlike in Studies 2 and 3, our analysis reveals no significant interaction of brand experience and NFU for interpersonal WoM; therefore we cannot support H2a. The share-and-scare strategy to avoid imitation could not be established in this study. As the unconfirmed negative influence of NFU in the fashion context cannot be clearly attributed to only one cause, there are several possible explanations that should be verified in further studies:

First, experiential stores are a common tool in the fashion industry. Unlike in other sectors (e.g., FMCG or transportation), experiential stores have been used here for many years, if not decades (Picot-Coupey, 2014; Surchi, 2011). As high-NFU consumers are aware of this, they have no fear of losing uniqueness through discussing their experience with the fashion brand in personal conversations.

Second, the opposite effects for H2a may also be justified by the different types of product categories, especially their place of consumption (private vs. public), and the fact that the stores’ visitors did not necessarily purchase products during their experiential store visit (i.e., participants in the experimental scenario did not receive any information about a purchase and actual store visitors were not chosen dependent on having made a purchase; in addition, all of the stores presented had a non-sales focus). Hence, they did not necessarily own the specific products or brands they would be spreading WoM about. In line with the findings of Cheema and Kaikati (2010) regarding people who did not own the product and had no intention of purchasing it, we found that high-NFU visitors were more likely to spread WoM for the publicly consumed fashion brand than for privately consumed brands. As individuals can express their uniqueness through their appearance, which is especially relevant in the fashion context, NFU may play a subordinate role in interpersonal communication for fashion brands (Lovett et al., 2013). High-NFU visitors of the fashion experiential store liked to share their experience with the brand as much as low-NFU visitors did because wearing unique clothes already allows high-NFU visitors to express their uniqueness through a readily visible brand name or logo. Therefore, they spread interpersonal WoM to inform close others at virtually no cost to them in terms of decreased uniqueness (Cheema & Kaikati, 2010). In contrast, because the consumption of chocolate is typically less conspicuous, high-NFU consumers who buy and consume it cannot easily express their uniqueness to close others non-verbally; they need to hold back information to maintain their uniqueness and therefore spread less interpersonal WoM.

Third, a further explanation for the non-significant effect in the fashion context might be the strength of the connection between consumers and the brand. Debenedetti et al. (2014) argued that a strong connection to a brand leads consumers to share experiences with close others. For all studies, we found a significant effect of brand familiarity or brand loyalty on interpersonal WoM (see Tables 2 and 3). Therefore, in the fashion context, brand familiarity might outperform the interaction effect of NFU. As fashion experiential stores are not as unique on social media as those focused on bikes or chocolate, the brand-familiar, social media content–aware customer would probably not take action to spread more eWoM, unlike non-familiar customers might be inclined to do.

Study 5

Method

Study 5 aimed to verify the results of Study 4. We recruited 492 German individuals (Mage = 37.18, SD = 12.24; 41.5% female; 16.7% students) via clickworker for a nominal payment and employed a 2 (store ephemerality: flagship vs. pop-up store) × 2 (NFU: low vs. high NFU) between-subjects design. For all items we used 7-point Likert scales.

First, we used the same elaboration exercise as in Study 3 to manipulate participants’ NFU to be high or low. A manipulation check (using five items from Tian & McKenzie, 2001; Cronbach’s α = 0.88) confirmed that the elaboration task had a significant effect on NFU (Mhigh NFU = 4.31; Mlow NFU = 3.59; p < .001). Afterward, participants indicated their familiarity with the same fashion retailer as in Study 4, measured with a single item in line with Milberg et al. (2010) that we used further as a covariate.

As in Study 4, respondents were randomly assigned to one of two store-type conditions and were shown the associated photos and videos. Afterward, they evaluated their retail experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.91), brand experience (Cronbach’s α = 0.94), intentions to spread WoM electronically (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) and interpersonally (Cronbach’s α = 0.93), and perceived store ephemerality. As a manipulation check indicated that participants perceived the ephemeral pop-up store to be significantly less temporally available than the permanent flagship (Mpop−up = 6.23; Mflagship = 3.25; p < .001), we further used this manipulation as a moderator.

Results

To deepen our investigation of the roles of store ephemerality and NFU, we performed a last round of moderated mediations (using PROCESS Model 21 with 10,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes, 2018).

Again, the results (see Table 1, Study 5) confirm H1: The positive effect of retail experience on brand experience (b = 0.66; p < .001) is further qualified by store ephemerality (b = 0.16; p = .027), with the effect being stronger for pop-ups (b = 0.82; p < .001) than for flagships (b = 0.66; p < .001). The results are depicted in Fig. 2 (Study 5).

According to H2a and H2b, and given the results of Studies 2 and 3, we expected high NFU to minimize the effect of brand experience on interpersonal WoM and bolster its effect on eWoM. However, as Study 4 revealed no significant interaction for interpersonal WoM, we manipulated NFU to gain more insights into the moderation effect (see Table 3, Study 5, for results).

In line with Study 4, our results indicate that the significant effect of brand experience on interpersonal WoM (b = 0.51; p < .001) is not further qualified by a significant negative interaction with NFU (b = −0.04; p = .574). Hence, we cannot find support for H2a. However, brand familiarity may offer some explanation for the increase in interpersonal WoM (b = 0.14; p = .008).

The results for eWoM replicate those of Studies 2–4. The significant direct effect of brand experience on eWoM (b = 0.54; p < .001) is further qualified by a significant interaction with NFU (b = 0.20; p = .021). The spotlight analysis reveals that high NFU has a greater effect on the influence of brand experience on eWoM (b = 0.73; p < .001) than low NFU does (b = 0.54; p = .001), thus supporting H2b (see Fig. 4, Study 5). Moreover, the results reveal that the indirect effect of retail experience on WoM through brand experience depends on perceived store ephemerality and NFU (index of moderated mediation: 0.03, 95% CI = 0.020, 0.079) (see Table 3, Study 5, for indirect effects).

Discussion

By manipulating both store ephemerality and NFU, Study 5 confirms that for experiential stores in a fashion context, NFU does not mitigate the impact of brand experience on interpersonal WoM. This may be because in such situations, consumers can communicate and maintain their uniqueness through their outward appearance. However, another explanation is that consumers might actually like to share their experience with emotional brands with beloved ones, regardless of NFU. In line with the previous studies and by extending existing research on both experiential stores and scarcity, we reaffirmed that pop-ups in contrast to flagships can generate even stronger brand experiences through retail experiences. Furthermore, Study 5 provides support for the idea that high-NFU consumers prefer to present their uniqueness by sharing their brand experiences with the public via eWoM. Finally, like in Study 4, the results for brand familiarity illustrate that an experiential store is an effective marketing tool for solving a positioning challenge, as fashion experiential stores induce positive eWoM among both new and existing customers.

Overall discussion

Existing literature on experiential stores largely points to the experience itself as a factor affecting consumer behavior, especially in terms of WoM, which is seen as a logical requirement for these stores–particularly pop-ups–to be effective (Jahn et al., 2018; Klein et al., 2016). Our results not only confirm the well-known effect of retail experience on brand-related WoM through brand experience but also expand our understanding of how WoM is affected by retail experience in experiential stores. Retail experience positively affects brand experience, especially when the store is (perceived to be) ephemeral, as is the case with pop-ups but not flagships. Moreover, our research corroborates the prediction that for high-NFU consumers, brand experience translates into increased WoM when communicating with distant others. For close others, we predicted the opposite. However, although the results of Studies 2 and 3 support our expectation, Studies 4 and 5 failed to find a significant interaction in the fashion context.

Theoretical implications

Encouraged by Robertson et al. (2018), whose key research propositions highlight a need to investigate the ephemeral and experiential quality of pop-ups in greater detail, this research provides several contributions. First, by demonstrating that ephemerality has a strong influence on consumers’ brand experience, which further heightens WoM, we add to current scarcity research and demonstrate the positive effect of pop-ups’ time scarcity for consumers and brands. Wu et al. (2012) found perceived scarcity to increase perceived uniqueness, Zhu and Ratner (2015) identified arousal as a consequence of limited availability. Contributing to these findings, we managed to show that experiential stores’ ephemerality may intensify the effect of a consumer’s perception of the store (retail experience) on their brand experience because it generates arousal. This is also an important contribution to the existing literature on experiential stores, which has largely neglected to consider one of the distinguishing features of experiential pop-up stores: transience (exceptions: Henkel & Toporowski, 2021; Henkel et al., 2022; Zogaj et al., 2019). Klein et al. (2016) determined that pop-ups’ hedonic shopping value, store uniqueness, and store atmosphere increase consumers’ WoM toward the brand, while brand experience mediates the effect. These findings are in line with flagship store literature attesting that a favorable retail experience translates indirectly through brand experience into brand-related WoM (Jahn et al., 2018). However, we were able to demonstrate that the retail experience alone is insufficient to explain brand experience and WoM in a temporary experiential store context, as the experience itself does not distinguish these stores from other, permanent experiential stores. Second, though experiential store literature has suspected NFU to be an important character trait and moderator, finding it to affect intention to visit (Henkel & Toporowski, 2021; Robertson et al., 2018), research has paid no attention to its impact on WoM. Together, our studies show that NFU plays a significant role in the relation between retail experience and WoM and thus contributes to experiential stores’ main goal of spreading WoM. Third, contributing to the findings of Cheema and Kaikati (2010), our results indicate the value of a more detailed view of the effect of NFU on WoM, suggesting a need to differentiate based on the audience’s closeness to the communicator (interpersonal vs. eWoM). These findings are in line with current literature on WoM and highlight the importance of NFU in effectively driving WoM.

Managerial implications

Experiential stores aim to generate positive WoM because it can exert great influence on consumption decisions. However, monitoring WoM performance to ensure effectiveness proves to be difficult. Our findings add to experiential stores’ communicational objectives and provide important implications for brands regarding the development of successful store concepts. Our study suggests that brands should highlight one of the unique qualities of pop-ups–their ephemerality–to generate WoM via brand experience. This could be reflected in their interior design by, for example, keeping the original configuration of the vacant store or integrating displays counting down the time until the store closes permanently (Surchi, 2011). Ephemerality may also be represented through performative aspects, such as requiring visitors to make a reservation (in the case of a familiar brand’s store) or including live performances; a non-conventional location; communication conducted exclusively through social media; or integration of multi-channel retailing. To make their temporal scarcity even more explicit, brands can design pop-ups to be nomadic by installing them in spaces such as shipping containers (Shi et al., 2019).

Furthermore, as our findings apply not only to brands that target high-NFU consumers but also to those targeting low-NFU consumers, brands should consider expanding their target visitor groups when launching experiential stores. Though high-NFU consumers monopolize eWoM, interpersonal WoM is spread by both high- and low-NFU consumers.

Consumers with a low NFU do not differ from high-NFU consumers in gender, marital status, age, education, employment status, or income. Although scarcity and exclusivity are often related to high costs, low-income consumers may also exhibit high NFU; this may be manifested by, for example, creating their own unique garments or shopping at vintage stores rather than through purchasing expensive clothes (Tian & McKenzie, 2001). In either case, to directly target visitors, experiential store staff may be able to identify high-NFU consumers by their outward appearance. Another indicator of high NFU may be the fact that one is visiting such an experiential store at all, as they high-NFU consumers prefer experiences that are unavailable to others (Fromkin, 1970; Henkel & Toporowski, 2021).

To target these visitors with a high NFU, experiential stores should highlight not only their ephemerality and scarcity but also the key element of experiential stores: unique experiences (Zogaj et al., 2019). High-NFU consumers may be drawn to a unique and distinctive store design (Klein et al., 2016; Robertson et al., 2018), limited edition products (Henkel & Toporowski, 2021; Henkel et al., 2022), or sensory stimulation and unique personalized interactions with the brand via elements such as media stations or interactive games (Klein et al., 2016; Niehm et al., 2006). Because high-NFU consumers prefer to spread eWoM, we suggest that brands targeting them place hashtags throughout the store to encourage the sharing of experiences via social media posts, which the brand can then track.

The creation of positive interpersonal WoM is also essential, especially for a brand’s profit, as recommendations by close others are perceived to be more authentic and trustworthy. To foster such WoM, experiential stores should clarify whether and how they could allay high-NFU consumers’ fears of losing their uniqueness. At the same time, experiential stores must attract low-NFU consumers, who tend to spread interpersonal WoM as opposed to eWoM. Although they are less drawn to scarcity and experiences, these customers could still be addressed to guarantee positive interpersonal WoM. To target low-NFU consumers, we advise brands to focus on benefits unrelated to uniqueness, such as functionality, hedonic value, or cognitive challenge (Vandecasteele & Geuens, 2010), while also offering standard, familiar products.

Furthermore, to generate the WoM desired by the brand, stores could even manipulate visitors’ NFU. To stimulate high NFU, the store could highlight the importance of individuality; when stimulating low NFU, the store could foster a sense of community to impress the importance of conformity (Cheema & Kaikati, 2010).

Limitations and avenues for future research

In interpreting our findings and continuing this line of research, it is important to recognize certain limitations of our work. With the field studies, self-reported measures of store visits may be subject to social desirability bias, while with the experiments, watching video footage is an imperfect simulation of a real-life retail experience. Still, our framework holds value and therefore should be applied not only to different familiar and unfamiliar brands and products but also to further actual store visits. Furthermore, qualitative, exploratory studies could be conducted to complement our quantitative findings and provide further explanations for consumers’ behavior. The ultimate test of the performance of experiential stores could be carried out through field experiments and natural interventions, such as store remodeling, although even a follow-up study regarding visitors’ actual WoM behavior would be useful. As ultimately we could not state for all cases that there is a negative interaction effect of NFU with brand experience on interpersonal WoM, research should investigate this relationship further.

In addition, as experiential stores are launched to offer visitors positive experiences around the brand (Dolbec & Chebat, 2013) and aim to generate positive WoM (Klein et al., 2016), we focused on positive experiences and positive WoM generation. However, future studies should investigate negative effects. In line with the expectancy-disconfirmation paradigm, it would be interesting to understand how visitors excited about visiting an experiential store would behave if they had a poor or unexpected experience, and how this could affect brand perceptions and WoM. Moreover, it is possible that a store’s ephemerality may have not only positive but also negative effects. Store ephemerality may hamper shopping enjoyment, trigger negative feelings, or reduce intention to browse (Kim & Kim, 2008; Kristofferson et al., 2017).

Furthermore, we did not account for the continuity between current experiences and previous and future ones. The creation of brand experience depends largely on preexisting brand experience (Brakus et al., 2009; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). As recent research has found that retail experience within experiential stores updates brand experience, but with a smaller impact than assumed (Jahn et al., 2018), the relation between previous, current, and future experiences must be investigated in greater detail.

Future studies should also delve deeper into analyzing ephemerality. Specifically, researchers should consider how ephemerality changes consumers’ perceptions of store and brand value (Lynn, 1991). To further understand the mechanisms behind ephemerality, it would be also an opportunity to replicate our studies in related contexts, such as flagship museums versus temporary exhibitions. In addition to store ephemerality, pop-ups may differ from other experiential stores in terms of store design characteristics such as occupying a non-traditional location or design novelty (de Lassus & Freire 2014; Robertson et al., 2018). Therefore, future research should concentrate not only on store ephemerality but also on further distinguishing characteristics to gain a deeper understanding of the success of temporary experiential stores.

Furthermore, as (temporary) experiential stores target consumers who seek uniqueness, high sensation, and social status (Henkel & Toporowski, 2021; Robertson et al., 2018)–needs that can be fulfilled by visiting an exclusive, ephemeral store–it is important to investigate the impact of self-staging on consumer behavior after the experiential store visit; these consumers are the ones who in principle would share their visits on social media to signal how in touch they are with new trends (Robertson et al., 2018; Warnaby et al., 2015). At the same time, experiential stores may be seen as temporal experiences that consumers seek out as a response to a sped-up culture. It would therefore be interesting to learn more about the link between experiential stores and escapism (Husemann & Eckhardt, 2019).

Finally, future research should consider the role that ephemerality and WoM play in experiential stores’ effects on long-term store and brand outcomes. It is not only well-established brands but also start-ups that open experiential stores–especially pop-ups–as these emerging brands often do not have their own store locations. By launching temporary experiential stores, they aim to build brand awareness (Picot-Coupey, 2014), which may be generated both directly through visiting and indirectly when visitors talk about the store and the brand, as Robertson et al. (2018) proposed. Our results indicate that ephemeral stores induce more arousal than permanent ones and thus contribute even more to WoM. Hence, we would assume that brand awareness might stand to benefit from the surprising character of ephemerality. This proposition must be verified by future research. For established brands, brand loyalty has been identified as a key goal of experiential stores, alongside WoM generation. However, details regarding the mechanism behind the effect of temporary experiential stores on brand loyalty and the role of ephemerality remain unclear (Zogaj et al., 2019). Furthermore, it is questionable whether consumers with a high NFU can even become loyal to a brand.

In conclusion, our results indicate that temporary experiential stores offer a win–win situation for customers and brands: While customers are granted the opportunity to experience a brand more intensely, brands can benefit from immediate positive WoM.

References

Aggarwal, P., Jun, S. Y., & Huh, J. H. (2011). Scarcity messages: A consumer competition perspective. Journal of Advertising,40(3), 19–30

Ames, D. R., & Iyengar, S. S. (2005). Appraising the unusual: Framing effects and moderators of uniqueness-seeking and social projection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,41(3), 271–282

Balachander, S., & Stock, A. (2009). Limited edition products: When and when not to offer them. Marketing Science,28(2), 336–355

Barasch, A., & Berger, J. (2014). Broadcasting and narrowcasting: How audience size affects what people share. Journal of Marketing Research,51(3), 286–299

Bardhi, F., & Eckhardt, G. M. (2017). Liquid consumption. Journal of Consumer Research,44(3), 582–597

Berger, J. (2014). Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology,24(4), 586–607

Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research,49(2), 192–205

Bickart, B., & Schindler, R. M. (2001). Internet forums as influential sources of consumer information. Journal of Interactive Marketing,15(3), 31–40

Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing,73(3), 52–68

Brock, T. C. (1968). Implications of commodity theory for value change. In A. G. Greenwald, T. C. Brock, & T. M. Ostrom (Eds.), Psychological Foundations of Attitudes (pp. 243–275). Academic

Burns, D. J., & Warren, H. B. (1995). Need for uniqueness: shopping mall preference and choice activity. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management,23(12), 4–12

Cheema, A., & Kaikati, A. M. (2010). The effect of need for uniqueness on word of mouth. Journal of Marketing Research,47(3), 553–563

Chen, Z. (2017). Social acceptance and word of mouth: How the motive to belong leads to divergent WOM with strangers and friends. Journal of Consumer Research,44(3), 613–632

De Lassus, C., & Freire, N. A. (2014). Access to the luxury brand myth in pop-up stores: A netnographic and semiotic analysis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,21(1), 61–68

Debenedetti, A., Oppewal, H., & Arsel, Z. (2014). Place attachment in commercial settings: A gift economy perspective. Journal of Consumer Research,40(5), 904–923

Dolbec, P. Y., & Chebat, J. C. (2013). The impact of a flagship vs. a brand store on brand attitude, brand attachment and brand equity. Journal of Retailing,89(4), 460–466

Dubois, D., Bonezzi, A., & De Angelis, M. (2016). Sharing with friends versus strangers: How interpersonal closeness influences word-of-mouth valence. Journal of Marketing Research,53(5), 712–727

East, R., Hammond, K., & Wright, M. (2007). The relative incidence of positive and negative word of mouth: A multi-category study. International Journal of Research in Marketing,24(2), 175–184

Eisend, M. (2008). Explaining the impact of scarcity appeals in advertising: The mediating role of perceptions of susceptibility. Journal of Advertising,37(3), 33–40

Franke, N., & Schreier, M. (2008). Product uniqueness as a driver of customer utility in mass customization. Marketing Letters,19(2), 93–107

Fromkin, H. L. (1970). Effects of experimentally aroused feelings of undistinctiveness upon valuation of scarce and novel experiences. Journal of personality and social psychology,16(3), 521–529

Grewal, D., Levy, M., & Kumar, V. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing,85(1), 1–14

Hamilton, R., Thompson, D., Bone, S., Chaplin, L. N., Griskevicius, V., Goldsmith, K., & Zhu, M. (2019). The effects of scarcity on consumer decision journeys. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,47(3), 532–550

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford

Henkel, L., Jahn, S., & Toporowski, W. (2022). Short and sweet: Effects of pop-up stores’ ephemerality on store sales. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,65, 102850

Henkel, L., & Toporowski, W. (2021). Hurry up! The effect of pop-up stores’ ephemerality on consumers’ intention to visit. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,58, 102278

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., & Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: what motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing,18(1), 38–52

Hoffman, D. L., & Novak, T. P. (1996). Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing,60(3), 50–68

Hollenbeck, C. R., Peters, C., & Zinkhan, G. M. (2008). Retail spectacles and brand meaning: Insights from a brand museum case study. Journal of Retailing,84(3), 334–353

Husemann, K. C., & Eckhardt, G. M. (2019). Consumer deceleration. Journal of Consumer Research,45(6), 1142–1163

Jahn, S., Nierobisch, T., Toporowski, W., & Dannewald, T. (2018). Selling the extraordinary in experiential retail stores. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research,3(3), 412–424

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing,57(1), 1–22

Kim, H., Fiore, A. M., Niehm, L. S., & Jeong, M. (2010). Psychographic characteristics affecting behavioral intentions towards pop-up retail. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management,38(2), 133–154

Kim, H. Y., & Kim, Y. K. (2008). Shopping enjoyment and store shopping modes: the moderating influence of chronic time pressure. Journal of retailing and consumer services,15(5), 410–419

Klein, J. F., Falk, T., Esch, F. R., & Gloukhovtsev, A. (2016). Linking pop-up brand stores to brand experience and word of mouth: The case of luxury retail. Journal of Business Research,69(12), 5761–5767

Kotler, P. (1973). Atmospherics as a marketing tool. Journal of Retailing,49(4), 48–64

Kozinets, R. V., Sherry, J. F., DeBerry-Spence, B., Duhachek, A., Nuttavuthisit, K., & Storm, D. (2002). Themed flagship brand stores in the new millennium: theory, practice, prospects. Journal of Retailing,78(1), 17–29