Abstract

Prior research on salesperson judgment and decision making (JDM) has been fragmented. After identifying how salespeople uniquely differ from other decision makers and unpacking how various personal selling issues can benefit from research in the JDM domain, the authors provide a framework to guide future research on salesperson JDM. The framework includes a research idea generation template to facilitate the identification of theoretically and substantively important research questions about salesperson JDM.

Similar content being viewed by others

In contrast with research on consumer behavior that has coevolved, if not been intertwined, with judgment and decision making (JDM) research, salesperson JDM has received much less research attention. The purpose of this commentary is threefold. First, we underscore that salespeople are very unique decision makers. Second, we identify substantive areas of professional selling that are ripe for JDM research. Third, we provide a three-step framework for marketing scholars who are interested in applying and extending traditional JDM theories to the study of salesperson JDM.

The widespread impact, key assumptions, and relevance of JDM research

JDM represents an entrenched domain that is comprised of various theories. Judgment refers to how people, groups, and organizations “assess, estimate, and infer what events will occur and what the decision maker’s evaluative reactions to those outcomes will be” while decision making refers to their process of choosing a course of action (Hastie 2001, p. 657).

JDM research impact

The widespread impact of and sustained interests in JDM are evident from the more than 10 review articles in Annual Review of Psychology on JDM. In addition to a rich JDM literature in various fields, including economics, finance, accounting, management, education, and medicine, JDM figures predominantly in consumer behavior research (Luce 2015). JDM research includes three main perspectives—normative, descriptive, and prescriptive—that cover the full range of how people should make decisions, how they actually decide, and how they can be trained to make better decisions (for a detailed overview of these perspectives, see Bell et al. 1988). In terms of levels of analysis, JDM research has examined decisions at the individual, group, and organizational levels, although a multilevel approach that takes into accounts the interaction of these levels is not widely adopted. In Marketing, the bulk of JDM research has been at the individual-level consumer.

Key assumptions in JDM research

Since JDM represents a domain that is comprised of various theories, the assumptions underlying these theories vary significantly. March (1994, p. 7) summarizes five key dimensions along which theories of decision making differ from one another. These include (1) rationality, or assumptions about whether decision makers are able to consider all the alternatives or only a few and whether they are able to consider them simultaneously or sequentially; (2) knowledge, or assumptions about the information decision makers have about the state of the world and other individuals; (3) individuals, or assumptions about the number of decision makers; (4) preferences, or assumptions about the preferences by which consequences and, therefore, alternatives are evaluated; and (5) decision rules, or assumptions about the decision rules that decision makers use to choose an alternative. As we allude to later, due to the uniqueness of salespeople as decision makers, a reexamination of these assumptions represent both opportunities and challenges for the study of salesperson JDM.

Why JDM research is relevant to sales research

In contrast with the long tradition of JDM research in consumer behavior, sales research that employs JDM theories is rather sparse. Early marketing research on salespeople has underscored the performance implications of salespeople’s ability to evaluate customer cues, know the customer needs, and engage in adaptive selling (Weitz 1978). Sixteen years after Weitz’s seminal work, March (1994) lamented the lack of research on JDM in sales, a gap that has not changed much in the last two and a half decades. This is surprising, given that salespeople constantly form judgments and engage in decision making in a complex and uncertain environment.

Three recent trends in professional selling have underscored why JDM is increasingly relevant to sales scholarship. First, the selling environment has become much more complicated, characterized by more knowledgeable customers, elevated competitive intensity, more demanding cross-functional coordination, and an increasing pressure to be efficient (Sleep et al. 2020). Second, the availability of observational data (e.g., customer relationship management [CRM] data, artificial intelligence [AI] platforms, recommendation technologies for sales calls) has greatly improved, allowing researchers to study JDM from a much more dynamic, realistic, and real-time approach. Third, the increasing pressure to multitask (e.g., between selling and providing services, between hunting and farming) under tight resource constraints necessitates research that enables salespeople to become more efficient in their resource allocation.

These trends have ushered in a renewed academic interest in salesperson JDM. This emergent stream has extended beyond salesperson ethical decision making (e.g., Schwepker et al. 1997) to examine salesperson judgments of potential outcomes (e.g., Bonney et al. 2016), salesperson-customer interactions (e.g., Homburg et al. 2014), effort allocation when multitasking (e.g., Lam et al. 2019; Mayberry et al. 2018; Van der Borgh and Schepers 2018), and the interplay of AI and salesperson JDM (Karlinsky-Shichor and Netzer 2021).

Nevertheless, salesperson JDM research has three key limitations. First, there is a lack of recognition of the uniqueness of salespeople as decision makers (i.e., how salespeople differ from other decision makers). Second, it is unclear what substantive personal selling issues can be examined as JDM issues. Third, there is no framework to guide research on salesperson JDM. As a result, it is still fragmented, unable to fully leverage the benefits of JDM research, and far from achieving the mainstream status that consumer JDM research holds.

Uniqueness of salespeople as decision makers

As human decision makers, salespeople are similar to JDM research participants in many ways; however, they are rather unique in many aspects, an issue that has not been clearly articulated in sales research. Based on our review of extant sales research, we contend that salespeople’s idiosyncratic decision-making context, their decision task characteristics, and the decision-making constraints to which they are subject necessitate a more integrated approach to studying salesperson JDM. In Table 1, we summarize these unique characteristics as the “3Cs” and underscore the research implications of these “3Cs” pertaining to the key dimensions of JDM assumptions and research design.

Decision-making context

Salespeople form judgments and make decisions in a complex and uncertain environment. First, salespeople make their decisions within the boundaries of the selling firm’s policies to which salespeople must adhere and organizational and group norms and values that are less explicitly stipulated but important nonetheless. Second, as boundary spanners, salespeople make their decisions while balancing their firm’s interests and customer interests, competition, and other outside stakeholders (e.g., regulatory entities). Third, salespeople may work in multiple teams (e.g., functional teams, key account teams, sales teams) and share sales credit with other team members and sometimes even with their managers. Fourth, their decision-making context is highly uncertain, ambiguous, and constantly changing. Finally, these contextual elements also vary by the sales force structure and the nature of the sales roles (e.g., Sleep et al. 2020). For example, before the COVID-19 pandemic, inside salespeople did not generally have much in-person interactions with customers, while field salespeople did. Compared with field salespeople, inside salespeople often suffer from higher levels of uncertainty because they do not have access to “private” customer information and rely more on input mediated by technology. These dissimilarities result in very different decision-making contexts between the two types of salespeople.

Decision task characteristics

As boundary spanners, salesperson selling tasks are unique. In Table 1, we summarize these characteristics based on Hackman and Lawler’s (1971) job characteristics. We also add cyclicality as an important unique characteristic of salespeople’s selling task: they are subject to a confluence of various cycles, including a sales quota cycle, a customer relationship cycle, a product life cycle, and a business cycle. Because salespeople’s tasks are characterized by high levels of skill variety, ambiguous task identity, high levels of significance, incomplete autonomy, delayed feedback, and high cyclicality, their JDM is naturally heterogeneous, both at the within-salesperson and between-salespeople levels. For example, salespeople are likely to rely on heuristics and the search for satisficing (i.e., not perfect but acceptable) decisions for complex tasks with a long sales cycle and high uncertainty such as solution selling. By contrast, they are rational maximizers in simpler tasks with shorter sales cycles and less uncertainty such as selling existing products. In addition, not all of salesperson decision tasks are selling tasks: salespeople also need to fulfill administrative and service tasks.

Decision-making constraints

Salespeople are constrained by limited resources, which has important implications on their preferences and decision rules (March 1994). While this constraint also applies to other consumer behavior JDM contexts, it is important to note that this issue is more severe for salespeople, given the unique context and task characteristics we have just discussed. Importantly, these resource constraints also vary over the different cycles. For example, as salespeople approach the end of the quota cycle, the motivation to achieve quick wins among those who are still far away from quota exacerbates the resource constraints and weakens the widely-adopted assumption of salesperson risk aversion. Moreover, as mentioned previously, salesperson JDM might involve more than just the focal salesperson. The involvement of multiple individuals and groups represents an important constraint of salesperson JDM, because such involvement may fundamentally change the decision rules.

The “3Cs” of decision-making context, decision task characteristics, and decision-making constraints have important implications for salesperson JDM research. In the last column of Table 1, we underscore how these unique characteristics of salespeople as decision makers pose challenges and opportunities for the study of salesperson JDM. On the one hand, they represent great challenges because they require scholars to reexamine many key assumptions of JDM theories and to come up with creative research designs (e.g., longitudinal design to account for lagged outcomes, multilevel models to account for multiple stakeholders involved in JDM). On the other hand, they create golden opportunities for scholars to investigate dynamic, realistic JDM issues that are not easily studied in, for instance, a static, scenario-based setting.

Substantive personal selling issues as JDM research questions

Research on salesperson JDM is rather fragmented. Therefore, we deem it necessary to provide a summary of key substantive areas in personal selling that can be asked as JDM research questions. As Table 2 summarizes, these substantive areas range from broad topics such as goal pursuit, ethical decisions, and career management to sales-specific topics such as pipeline management, incentive plans, pricing, and interactions with customers, peers, and technologies. Adopting the lens of JDM theories, researchers investigating substantive issues in professional selling can examine each of these areas by focusing on four “W” issues, namely, (1) Why salespeople take a specific action or a sequence of actions (outcome-based JDM), (2) What action salespeople take (behavior-based JDM), (3) When an action is taken (timing-based JDM), and (4) How salespeople make these decisions (process-based JDM). It should be noted that while we present the representative research questions as if salespeople did not make several sales decisions at the same time, they do tackle various decisions simultaneously. Furthermore, many salesperson decisions are temporally interrelated, such that a prior action can have important implications on subsequent actions. Because of this temporal interrelation of their decisions, salespeople are both the products of and the producers of the above-mentioned “3Cs”—they can proactively alter these “3Cs” through their serial decisions.

For example, researchers who study salesperson JDM when prospecting for new customers can investigate various questions. These include: (1) Why: the short- and long-term implications of salespeople’s decisions when prospecting; these implications can be for the focal salesperson or other stakeholders, (2) What: salesperson JDM on what prospect to focus on (e.g. attributes of prospects such as prospect size and prospect uncertainty), (3) When: their priorities regarding searching for new customers (i.e., hunting) and leveraging existing customers (i.e., farming), and (4) How: decisions between engagement with a prospect alone or forming ad-hoc teams; decisions on what selling strategies and tactics to use. These decisions are sometimes made in a sequential manner while some are temporally interrelated. Specifically, salespeople may first make the decision on task prioritization between hunting and farming. Then, if a focus on hunting is warranted, they generate the criteria to evaluate prospects, decide what information about prospects they need to collect and share, and with whom, and determine whether they need to push the established or new products, and so on. If their actions in the prior period were not effective, salespeople then may engage in proactive behavior to influence the factors that they think may cause such failure, and such action may spiral out of control (e.g., escalation of commitment; Mayberry et al. 2018) or put them back on the right track. Taken together, professional selling represents a rich, highly dynamic context to examine substantively important and theoretically interesting JDM issues.

Toward a framework to study salesperson JDM issues

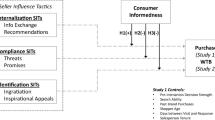

In light of the above discussion, we offer a three-step framework to study salesperson JDM issues. Our framework, summarized in Fig. 1, builds on the adaptive approach to decision making that accounts for the decision makers, their tasks, and the social contexts (Payne et al. 1993).

-

Step 1:

Have a deep understanding of the assumptions of JDM theories before applying research to salesperson JDM

Given the uniqueness of salespeople as decision makers relative to typical participants in JDM research, as we pointed out in Table 1, salesperson JDM represents a phenomenon that can easily violate one or more assumptions of existing theories. Therefore, although existing JDM theories provide useful conceptual foundations for salesperson JDM research (e.g., utility maximization under the normative, highly rational perspective versus heuristics and biases under the descriptive, less rational approach), we urge marketing scholars to clearly identify the assumptions of the JDM theories they apply when studying salespeople as decision makers. The five key assumptions of JDM theories as summarized by March (1994) provides a useful checklist for this purpose.

-

Step 2:

Integrate JDM theories with sales research

Drawing from extant sales research, we have identified the “3Cs” uniqueness of salespeople as decision makers (see Table 1). We contend that an examination of salesperson JDM issues necessitates an integration of these “3Cs” with the key assumptions of JDM theories. However, this integration poses several challenges and opportunities, both conceptual and empirical. Conceptually, while this overlay reveals multiple contingencies that require skillful theoretical development, it enables marketing scholars to generate novel research questions that traditional JDM has yet to explore. To facilitate such an integration, we provide a research idea generation template in Table 3 that overlays key assumptions of JDM theories on the “3Cs” of salespeople as decision makers. As Table 3 illustrates, this overlay produces several interesting research questions that account for the decision makers, their tasks, and the social contexts.

For example, salespeople differ in terms of their rationality, knowledge, the number of people involved in their decisions, their preferences, and decision rules. More experienced salespeople have more extensive customer-need knowledge than novices, yet young salespeople are generally more comfortable with new sales technologies (e.g., AI-based technologies) that facilitate their decision making. For some decisions, salesperson JDM might be individualistic, while in others, such as team selling, decisions might be made collectively. Furthermore, depending on their sales roles, some salespeople are responsible for making fairly simple decisions that can be handled in a highly rational manner while others handle complicated, uncertain tasks (e.g., solution selling) that must be acted upon using heuristics. These two types of sales roles would call for very different theories to explain their JDM processes.

As another example, Karlinsky-Shichor and Netzer (2021) ingeniously use historical data of salespeople’s pricing decisions to develop a ‘digital twin’ that can either replace or augment salesperson decision making. They show that a hybrid model (i.e., one that does augment salesperson decision making) is superior. Using Table 3 as the framework, marketing scholars can further explore questions such as: How do differences in task characteristics (e.g., product vs. solution selling) affect the utility of digital twins? How does salesperson perception of their selling self-efficacy and their customer relationship quality affect the utility of the digital twin? Therefore, Table 3 provides an easy-to-implement yet effective tool for marketing scholars to integrate JDM theories with sales research to account for the “3Cs” uniqueness of salespeople. Blind application of JDM theories in the personal selling context is not advisable.

Empirically, this theoretical integration poses significant challenges because it considerably increases the complexities of research design and model specification to appropriately identify the causality and account for the dynamics of salesperson JDM. We believe that sales scholars can achieve these goals by combining the increasing availability of data in the sales domain with creative and rigorous research designs. For example, scholars can now use text-mining tools to analyze CRM logs to reconstruct the dynamics of salesperson JDM when prospecting. They then can also augment this secondary data with a survey and/or experiments to parse out the underlying psychological processes.

-

Step 3:

Enhance managerial relevance

An important requisite of sales research is managerial implications. To that end, we have outlined a number of substantively important research questions in personal selling that can be framed as interesting JDM issues and how scholars can leverage theories in both JDM and sales domains to generate specific questions (see Tables 2 and 3, respectively). Furthermore, we propose three key questions marketing scholars should ask themselves: Does their research about salesperson JDM result in recommended actions that (1) is not viable, such as requiring a firm to customize its policies by salespeople, (2) put too much uncertainty on salespeople, and (3) create a hostile sales climate? For effectiveness, firms can offer different incentives to different salespeople (e.g., by career stage, past performance). However, for the obvious reason of efficiency in implementation, firms generally cannot have too much customization in their sales force policies and need to adopt a balanced approach. Furthermore, it is simply unrealistic for firms to have a sales climate that entirely shifts the burden of uncertainty from the firm to salespeople or is too hostile. In the end, firms are expected to treat and retain salespeople as talents whose personal histories, successes and failures are intertwined with the firm’s, rather than anonymous, no-strings-attached experiment participants.

Conclusion

The late Clayton Christensen, architect of the theory of “disruptive innovation,” explained why he studied the disk drive industry using an analogy of fruit flies. He noted that companies in the disk drive industry have very short life cycles—like fruit flies—and therefore are ideal to investigate change. In line with this analogy, we posit that salesperson JDM represents a gold mine for JDM research because it provides a naturally complex decision-making setting that allows research to move away from extreme reductionist approaches and develop novel JDM and sales theories that better explain salespeople as decision makers.

In this commentary, we articulate how salespeople represent unique decision makers in many important aspects and identify several substantive issues in personal selling that are ripe for JDM-based research. Accordingly, we provide several recommendations for sales scholars to consider when applying traditional JDM theories to studying salespeople. We cannot emphasize enough the importance of future research accounting specifically for the purposive JDM of salespeople as they do act thoughtfully, adapting to the complicated context and the tasks at hand and proactively changing their decision-making context through their behavior. Such a dynamic perspective represents opportunities to leverage newly-developed methods and troves of real-time secondary data to study and build new JDM theories.

References

Bell, D. E., Raiffa, H., & Tversky, A. (Eds.). (1988). Decision making: Descriptive, normative, and prescriptive interactions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bonney, L., Plouffe, C. R., & Brady, M. (2016). Investigations of sales representatives’ valuation of options. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(2), 135–150.

Hackman, J. R., & Lawler, E. E. (1971). Employee reactions to job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 55(3), 259–286.

Hastie, R. (2001). Problems for judgment and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 653–683.

Homburg, C., Bornemann, T., & Kretzer, M. (2014). Delusive perception—Antecedents and consequences of salespeople’s misperception of customer commitment. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(2), 137–153.

Karlinsky-Shichor, Y., & Netzer, O. (2021). Automating the B2B salesperson pricing decisions: Can machines replace humans and when?. Available at SSRN 3368402.

Lam, S. K., DeCarlo, T. E., & Sharma, A. (2019). Salesperson ambidexterity in customer engagement: Do customer base characteristics matter? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(4), 659–680.

Luce, M. F. (2015). Consumer decision making. In The Wiley Blackwell handbook of Judgment and Decision Making, 1st edition, edited by G. Keren and G. Wu. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 875–899.

March, J. G. (1994). A primer on decision making: How decisions happen. New York: Free Press.

Mayberry, R., Boles, J. S., & Donthu, N. (2018). An escalation of commitment perspective on allocation-of-effort decisions in professional selling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(5), 879–894.

Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1993). The adaptive decision maker. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schwepker, C. H., Ferrell, O. C., & Ingram, T. N. (1997). The influence of ethical climate and ethical conflict on role stress in the sales force. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 99–108.

Sleep, S., Dixon, A. L., DeCarlo, T., & Lam, S. K. (2020). The business-to-business inside sales force: Roles, configurations and research agenda. European Journal of Marketing, 54(5), 1025–1060.

Van der Borgh, M., & Schepers, J. (2018). Are conservative approaches to new product selling a blessing in disguise? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(5), 857–878.

Weitz, B. A. (1978). Relationship between salesperson performance and understanding of customer decision making. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(4), 501–516.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. John Hulland, Prof. Mark Houston, and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Mark Houston served as Editor for this article.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lam, S.K., van der Borgh, M. On salesperson judgment and decision making. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 49, 855–863 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00775-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00775-1