Abstract

The past few decades have witnessed a significant increase in the number of cross-border strategic alliances among firms. We focus on the role of alliance expertise (alliance experience and diversity of partners) and alliance governance (horizontal vs. vertical alliances and joint venture vs. other alliances) in global innovation generation. We also examine the effect of these variables on the financial performance of the focal firm. The conceptual model is tested using an empirical analysis of cross-border alliances formed by U.S. pharmaceutical companies from 1985 to 2008. We find that while prior alliance experience has a positive association with global innovation generation, diversity of partners has a negative relationship. In addition, whether the alliance is horizontal or vertical has no bearing on the innovation generation, but joint ventures are associated with more global innovation generation than other types of alliances. Finally, as global innovation generation increases, financial performance increases up to a point but thereafter exhibits a negative relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globalization and technological advances have resulted in a significant reconfiguration of cross-border business-to-business relationships and the way these relationships contribute to organizational functioning and performance. The locus of such business-to-business relationships and the impact of such relationships in organizational activities, such as innovation generation and customer relationship management, have taken on a global perspective. With the advent of the “flat world” (Friedman 2005) and a “tectonic shift” (Sheth and Sisodia 2006) in the way markets and organizations interact in the global setting, organizations can now collaborate “seamlessly” across countries and time zones. Although there are several examples of successful alliances (e.g., Inkpen 2005; Inkpen and Wang 2006), if they are not designed, understood, and managed well, transaction costs (Coase 1937; Williamson 1985) can make knowledge transfer and global innovation generation activities both costly and ultimately lead to poor financial performance. For example, outsourcing contracts have been cancelled in several instances (e.g., Corcoran 2004), and the benefits of such arrangements over the long run for both knowledge creation and financial output have been questioned (Harland et al. 2005). Good alliance management can result in innovation generation (Rothaermel and Hess 2010), but whether alliance management alone leads to firm performance or whether innovation is a precursor to financial performance is unknown. Thus, both academic research and practice can benefit from a careful examination of the alliance characteristics and the effect of globalization of innovation activity on firms’ performance.

This study focuses on two key research questions: (1) Are alliance expertise and alliance governance related to the focal firm’s global innovation generation? and (2) Does the relationship between alliance characteristics and global innovation generation affect the firm’s financial performance? We next briefly describe the substantive and managerial context of these research questions and delineate the relevance and timeliness of the need for research in this domain.

Business-to-business relationships in the value chain are central to the domain of marketing (Boyd and Spekman 2008; Ghosh and John 2005; Swaminathan and Moorman 2009), as is the creation of value through global innovation in alliances, including buyer-seller relationships (Roy et al. 2004; Wilson 1995). Marketing scholars have focused a great deal on the downstream aspects of the new product development (NPD) process, including studying distribution and branding (Nygaard and Dahlstrom 2002; Rust et al. 2004), while upstream strategy processes corresponding to idea generation and alliance structure and governance have been largely left to strategy scholars, resulting in a decline in marketing’s influence on firm strategy formulation (Day 1992; Kerin 1992; Varadarajan 1992). This decline of marketing’s influence on strategy has continued (Chandy 2003), and examining the organizing mechanisms for innovation has been a challenge for marketing scholars (Hauser et al. 2006). The current research answers calls for further research in marketing to examine organizational issues and particularly upstream alliances for early stages of the NPD process, such as idea generation, access of global markets through innovation, and the impact of these strategic actions on firm’s financial performance (Han et al. 2001).

Previous conceptualizations of global innovation generation in business-to-business relationships have recognized that knowledge flow takes place from firm to alliance to markets (Almeida et al. 2002). Today, global outsourcing of services is rapidly increasing. Typically, outsourcing begins as a market transaction, and given the “sticky” nature of tasks (in our context, the word “sticky” means that the knowledge is ingrained in the organizational culture and routines and it is difficult to acquire, transfer, and use (von Hippel 1994)), these relationships become alliances over time because of the breadth of collaboration. Thus, knowledge flow in firms may follow a path such as markets → alliances → firms (e.g., Daksh acquired by IBM; Slater 2004). Converting an alliance into ownership can be a major distraction for focal firms. In contrast, markets are incapable of combining sticky knowledge, and therefore good alliances that work can be an ideal midpoint. Understanding how alliances function in terms of global innovation generation and impact financial performance can provide valuable insight into the forms of governance that allow for the effective cross-border transfer of knowledge.

Over the past two decades, there has been increasing scholarly interest in international alliances and the creation of knowledge (Simonin 2004). These alliances have been examined in the context of important issues, such as the role of culture (Bhagat et al. 2002; Morosini et al. 1998), the need to transfer personnel (Almeida and Kogut 1997), the stickiness and adaptation of new knowledge generated (Jensen and Szulanski 2004), the path dependence of new knowledge generated (Song et al. 2003), and NPD activities and global innovation generation (e.g., Wind and Mahajan 1997; Wuyts et al. 2004). Nonetheless, the relationship between globalization of innovation in the context of alliance activities and how they are related to firms’ financial performance have not been explored. This article addresses these important issues using global innovation generation as a study context.

The article makes several unique contributions. First, by studying the role of alliance characteristics in global innovation generation, we expand our knowledge of alliance management in influencing globalization of innovation activity. Second, by linking the alliance characteristics and global innovation generation to financial performance, we highlight the role of these factors in the financial performance of the focal firm. Third, by focusing our empirical analysis on the pharmaceutical industry, we add a sectoral dimension to our research. In recent years (e.g., Rothaermel and Hess 2010; Yeniyurt et al. 2009), practitioners as well as academic researchers have highlighted the importance of the pharmaceutical industry to the world and U.S. economies and to the knowledge-intensive nature of the early stage of NPD.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: We present our conceptual framework and a model of alliance characteristics, global innovation generation, and financial performance. Next, we develop hypotheses that link global innovation generation with both alliance activity and firms’ financial performance. Then, we present our empirical analyses and discuss the results. We conclude with a discussion of the theoretical implications and managerial usefulness of our findings and future research directions.

Conceptual framework

We conceptualize that the focal firm’s alliance expertise characteristics and alliance governance characteristics are related to its global innovation generation, the key feature of our framework. In turn, the firm’s global innovation generation and alliance characteristics are related to the focal firm’s financial performance. Our framework underscores the possibility that the alliance characteristics can have a direct relationship to the firm’s financial performance as well as an indirect relationship through the alliance characteristics’ relationship to global innovation generation. In summary, the framework focuses on the following links:

-

(1)

alliance characteristics → global innovation generation,

-

(2)

global innovation generation → financial performance, and

-

(3)

alliance characteristics → financial performance.

We present our conceptual model of alliance characteristics, global innovation generation, and financial performance in Fig. 1. In essence, the framework shows two models: one in which global innovation generation is the focal outcome construct and one in which the outcome is the focal firms’ financial performance. Note that our model represents the notion that the total effect of alliance characteristics on financial performance comprises two components: the indirect component that operates through the mediating variable of global innovation generation and the direct component that operates as a direct link to performance.

Given the complex nature of business-to-business relationships in the context of innovation generation, rather than one theory, we use three relevant theories to discuss the hypotheses. In our model, we view the direct effects of alliance expertise and governance on firm performance from the perspectives of transaction cost analysis (TCA) and the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm (Barney 1991; Morgan and Hunt 1994; Williamson 1985). Conceptually, TCA in the alliance context is the ability of partners to work effectively together based on experience with prior alliances with the same or different partners. RBV in our conceptual context involves the physical and explicit skill resources that partners bring to the alliance. These resources and skills are complementary between partners and in combination can deliver better performance for the alliance. TCA explicitly views the firm as a governance structure, whereas the RBV perceives it strictly as a production function (Rindfleisch and Heide 1997). For understanding the indirect effects of alliance expertise and alliance governance through global innovation generation, we also draw on the conceptual dimensions of the knowledge-based view (KBV) of the firm (Grant and Badden-Fuller 1995). The KBV perspective on alliances involves the domain and execution knowledge of the alliance partners that goes beyond the explicit considerations of RBV. Knowledge can be combined and lead to innovation (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). Thus, our research uses TCA and the RBV as overarching theories, while integrating the KBV in the formulation of our hypotheses related to global innovation generation. We view relationship marketing theory as a derivative of the TCA approach. We next provide a brief discussion of each construct in our model.

Global innovation generation

Conceptually, global innovation generation can take place in a foreign market in the early stages of the NPD process, including idea generation and concept selection (Gilbert and Newbery 1982; Han et al. 2001), or in the later stages, including international marketing-type adaptations in branding, packaging, or distribution (Lee and O’Connor 2003). Our focus is on the innovation outcome in upstream alliances or early stages of the innovation process.

Global innovation generation and larger macro constructs, such as knowledge transfer and globalization of innovation, have engaged strategy scholars since the 1990s (e.g., Gulati 1995). This scholarly focus has increased given the importance of the KBV in understanding firm strategies and performance (Grant and Badden-Fuller 1995; Kogut and Zander 1993). Within this literature stream, scholars have investigated the kinds of alliances that might help or hinder knowledge transfer, including joint ventures (JVs), research-and-development (R&D) alliances at the same point of the value chain, and contractual buyer-seller arrangements (Dahlstrom et al. 1996). Since the turn of the millennium, global outsourcing and alliances in knowledge-intensive industries have become prominent in managing innovation generation. Thus, the focus of our theoretical development and empirical testing is the role of alliance expertise and alliance governance in effective innovation generation for the focal firm and, in turn, their effect on the focal firm’s financial performance.

Alliance characteristics

At the level of the single alliance, Kale and Singh (2009, p. 48) provide a taxonomy of the key success factors around the phases of the alliance life cycle. These life-cycle stages are alliance formation and partner selection, alliance governance and design, and post-formation alliance management. Given marketing scholars’ intense scrutiny of post-formation alliance management, we extend a marketing view to the early stages of Kale and Singh’s taxonomy through alliance formation and partner selection and alliance governance and design. In the former, we investigate alliance expertise, and in the latter, we examine alliance governance. Thus, our study complements the current research while extending it in a significant way.

Alliance expertise

Alliance expertise refers to the focal firm’s expertise in managing cross-border alliances effectively. Management of inter-firm alliances is a skill that has sparked many high-tech companies to create an alliance management function. For example, Gueth et al. (2001) report that Eli Lily was an early implementer of the formal alliance management function. We conceptualize two dimensions of alliance expertise—namely, alliance experience and diversity of partners.

Alliance experience

The level of alliance experience is captured through the frequency of partnering or the number of alliance partners a firm has. Alliances for R&D involve partnerships in which firms come together to share complementary know-how in fast-changing fields (Powell 1998; Powell et al. 1996), such as the high-tech, financial services, and pharmaceutical industries. Such collaborations enable the joint deployment of efforts and resources in fields that are changing and have great competitive pressure. Managing several alliances aids the firm in developing its alliance expertise.

Diversity of partners

The diversity of partners refers to collaborations on projects with different partners (Wuyts et al. 2004). Uzzi (1997) suggests that having diverse partners enhances the vision of both partners and may help in innovation. Along the same lines, in the hard disk drive industry, Christensen (1997) finds that new suppliers were the ones that helped innovation. While diverse partners can enhance new knowledge, they can also lead to lesser efficiency and trust during the establishment of routines (Gulati and Kletter 2005).

Alliance Governance

Alliance governance comprises the mechanisms, both contractual and ownership (Contractor and Lorange 2002), that enable the focal firm to generate innovations and increase financial performance. We conceptualize alliance governance as vertical versus horizontal alliances and JV versus other types of alliances.

Vertical versus horizontal alliances

Strategic alliances involve contractual interdependence with partners either vertically or horizontally (Rindfleisch 2000). Vertical relationships in the upstream value chain of the focal firm (Dyer 1996; Lorenzoni and Lipparini 1999) involve firms that supply equipment, raw materials, components, or input services. Horizontal relationships at a similar point of the value chain (Ahuja 2000; Jap 1999) involve firms in the same industry but in different niches. In these strategic arrangements, the focal firm may collaborate with a series of suppliers, as in the auto industry (Clark and Fujimoto 1991) or the pharmaceutical and software industries (Hagedoorn 1993). The nature of such interdependence is that the two firms do not compete for exactly the same customers. Thus, for example, Coca-Cola may have a strategic alliance with Nestlé in markets in which they both target different sets of customers.

JVs versus other alliances

Joint ventures are another form of alliance governance that has been studied extensively (Inkpen and Beamish 1997). International JVs are known to have high failure rates and high management costs (Kogut 1988; Porter 1987), challenges in sharing proprietary knowledge, and the “appetite for control” (Hagedoorn 2002) between partners.

Despite these well-known problems, JVs allow direct control by the focal firm and better management of intellectual property and innovation generation (Das and Teng 2000). Similarly, increased opportunities for monitoring and control allow for better financial performance (Fang et al. 2008).

Financial performance

Our outcome variable in the investigation of alliance expertise, alliance governance, and global innovation generation is firm financial performance. In the second stage of our model (Fig. 1), we investigate the direct impact of global innovation generation on financial performance. We also investigate the impact of alliance expertise and alliance governance on financial performance.

Development of hypotheses

Alliance characteristics and firm performance

The total effect of each alliance characteristic on financial performance derives from the indirect effect through the mediating construct of global innovation generation, as well as any remaining residual effect from the direct effect. The following discussion pertains to the total effect of each alliance characteristic on financial performance.

Number of global alliance partners and firm financial performance

By dealing with many alliance partners, focal firms learn how to manage partners from routines, systems, and the atmosphere of the relationship (Gadde 2004). This firm learning is about managing inter-firm relationships and follows indirectly from TCA theory. Although dealing with the same partner reduces transaction costs, the aggregate transaction costs for every new partner or portfolio of partners decrease as the focal firm becomes used to managing partners. This ability to better manage alliances leads to better financial performance (Sarkar et al. 2001b).

There is growing evidence (Anand and Khanna 2000; Kale et al. 2002) that alliance expertise positively affects firm performance. For example, Hoang and Rothaermel (2005) find that general alliance management skills positively affect the performance of the joint project. Hoffmann (2005) suggests that a portfolio of alliances and an alliance management function should result in improved financial performance.

According to the RBV perspective, firms that deal with several partners gain access to a variety of skills and capabilities that can affect research productivity positively (Deeds and Hill 1996; Shan et al. 1994) and result in better financial performance. In a similar vein, Mahajan et al. (2002) argue that winners of the 2000 dot-com bust should have had more alliances. The theoretical rationale is compelling in that merely having the experience of managing many alliances enhances the focal firm’s ability to produce results and increase financial performance. Thus, we posit that experience with a large number of partners should help the focal firm’s financial performance.

-

H1:

As the number of partners in the focal firm’s past alliances increases, the total effect on financial performance increases.

Diversity of partners and firm financial performance

From an RBV perspective, we conceptualize diversity of partners in our formulation as a partnership between firms with complementary skills and resources (Sarkar et al. 2001a). The partners trust each other’s competence (Sako 1992) before contracting and therefore try to work together as a team to contribute to business results. The ability to bring in a diverse partner and assimilate the skills and resources for better financial performance has become more important in a globalized, technologically connected world.

From a TCA perspective, when partners can specify in advance the complementary skills and resources they bring to the relationship and clearly articulate mutual expectations, there is little dispute as joint work gets underway. After initial transaction costs are lowered through awareness and exploration (Dwyer et al. 1987), the partners develop commitment and an ability to work together effectively. Underlying the diversity of partners is the alliance expertise skill a focal firm develops. The firm formulates processes and routines that enable it to develop transaction-specific investments to improve the performance (Yu et al. 2006).

-

H2:

As the diversity of partners in a firm’s past alliances increases, the total effect on financial performance increases.

Vertical versus horizontal alliances and firm financial performance

Vertical alliances involve supply by an upstream supplier to the downstream focal firm or supply by the focal firm to a downstream partner. Transaction cost theorists (e.g., Williamson 1985) have argued that the reduction of transaction costs involves an association with a supplier in which both parties develop a long-term relationship of commitment and trust (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Competition is minimal between vertical partners, and the emphasis is on building an efficient, agile, and responsive supply chain (Christopher 2000). Such vertical alliances develop familiarity and routines to deal with the downstream partner and enhance efficiencies. This enhanced efficiency results in better financial performance for the focal firm.

We conceptualize horizontal strategic alliances as occurring at the same point in the value chain (Nygaard and Dahlstrom 2002; Rindfleisch 2000). However, when we compare horizontal and vertical alliances, horizontal alliances have a competition element that should decrease the overall performance impact on the focal firm. For example, horizontal alliances can create competitive feelings of rivalry, and such feelings will ultimately result in reduced financial performance. For example, Gimeno (2004 p. 822) finds that because of rivalry in the airline industry, horizontal alliances are favored only when partners “co-specialize” or invest in partner specific assets. When horizontal alliances become formalized as mergers, assets of the target firm may be divested, and such divesture can also lead to lower financial performance (Capron 1999; Capron and Hulland 1999). In contrast, vertical relationships are clear-cut in terms of resources, skills, and buyer-seller relationship building.

From the perspective of RBV, vertical alliances provide the context in which the exchange of critical complementary skills and information can occur (Achrol 1991) and can bring different sets of resources and capabilities to the partnership. In contrast, horizontal partners compete for the same resources in the same market (Lieberman and Montgomery 1998). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

-

H3:

As the proportion of vertical alliances relative to the total number of alliances increases (compared to horizontal alliances), the total effect on financial performance increases.

JVs and firm financial performance

Historically, JVs have been the preferred method of international market entry (Ekeledo and Sivakumar 1998) because of the appropriate level of monitoring and control the focal firm can exercise in its foreign operations that also govern its financial performance. The RBV suggests that JV partners come together with different sets of resources and capabilities that enhance the relationship; this is especially the case in a technologically turbulent environment (Song et al. 2003). Such international JV alliances show improved financial performance, and according to Lyles and Salk (1996), the RBV is an appropriate theoretical lens to study the performance of international JVs.

In addition, JVs provide the context in which strong social contracts between the firms can be developed. Consistent with the TCA framework (Williamson 1985), in light of the social contract, the general effect of monitoring on a party’s behavior is a reduction in opportunism (Heide et al. 2007), resulting in an improvement in the focal firm’s financial performance.

With their range of objectives such as market entry, distribution, NPD, and R&D, JVs have become common. The TCA perspective (Kogut and Singh 1988) suggests that a JV allows for direct monitoring and control by each partner through formal board membership and sometimes partnership in managing day-to-day operations. Despite the well-known tensions surrounding JV governance (Fryxell et al. 2002), research suggests that both RBV and TCA perspectives explain the positive correlation between the JV form of alliances and firm financial performance. For example, Fang et al. (2008) studied Chinese JVs and found that the partners’ resource deployments enhanced financial performance. We theorize that the focal firm improves its performance because the overall JV’s performance improves through the use of social contracts structured through both formal board meetings and daily operations. With this theorizing, we argue that the overall performance impact of JVs is positive. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

-

H4:

As the proportion of JV alliances relative to the total number of alliances increases, the total effect on financial performance increases.

Alliance expertise and global innovation generation

Number of global alliance partners and global innovation generation

Using a TCA perspective, we define alliance experience as the past experience of the firm in managing global alliances, capturing lessons learned, and deploying the experience in management of future alliances (Heimeriks et al. 2007; Kale et al. 2002; Reuer et al. 2002). Although extensive research has shown that alliances help firms expand their knowledge and market base, the impact of firms’ alliance activity on global innovation generation at the firm level remains unexplored. Likewise, although prior research has suggested that global innovation generation between partners commonly occurs in alliances, it has not yet been shown that an increase in the level of alliances leads to an increase in the level of global innovation generation. Several scholars (Hagedoorn 2002; Powell 1998; Powell et al. 1996) have pointed out that R&D alliances between firms are particularly useful when the industries are high-tech and facing rapid technological change. Multiple alliances for different knowledge domains are flexible and effective in creating cross-border knowledge for the focal firm.

Thus, following a KBV perspective, we expect that the level of global alliances is positively related to the level of global innovation generation. First, the interaction between international alliance partners can directly result in global innovation generation because of knowledge transfer from one partner to the other (e.g., Dhanaraj et al. 2004; Simonin 2004). Such knowledge transfer creates new knowledge, such as in the case of NPD collaboration. Second, because alliances increase firms’ knowledge base, they indirectly enhance firms’ incentives to grow internationally (Buckley and Casson 1976; Kogut and Zander 1993).

Experience with several alliance partners exposes the focal firm to a range of product and market conditions (Anand and Khanna 2000) and enhances its learning with regard to managing alliances. Cohen and Levinthal (1990) call this the “learning to learn” ability. Firms develop routines in terms of both learning and teaching their alliance partners how to work with them on projects.

If a focal firm has had more alliances in the past, it most likely developed routines, systems, and strategies to facilitate global innovation generation. According to TCA and the KBV, alliance partners become better at sharing, learning, and developing innovations in the subject domain of the alliance. Thus, we capture this increased ability for global innovation generation due to the number of past alliances as follows:

-

H5:

As the number of partners in a firm’s past alliance increases, global innovation generation increases.

Diversity of partners and global innovation generation

The diversity of partners occurs when partners of an alliance are new and have no prior experience with a specific partner. In this case, following a KBV perspective, the focal partner is able to “explore” new knowledge (March 1991) that the diverse partner brings to the alliance. In contrast, similar or repeated partnering offers firms the opportunity to “exploit” any overlapping knowledge (March 1991) that results in improvements in performance or lowering of cost. As mentioned previously, Christensen (1997) discovered that entire supplier industries can became extinct because of the actual or perceived inability of existing partnerships to solve a problem in a technologically changing environment. In the hard disk drive industry, Christensen found that new industries were established that successively replaced the eight- and five-inch supply industry with smaller sizes and superior performance. Relatedly, according to Wuyts et al. (2004), similar partners reduce the financial impact of global innovations.

According to the principles of TCA, working with the same partners involves low transaction costs because routines are familiar to both parties. However, new partners involve high transaction costs because both firms must learn about each other and how to work together (Sampson 2005). Conversely, the KBV of the firm suggests that diverse partners bring different knowledge sets to the alliance and that there is low knowledge redundancy (Sivakumar and Roy 2004). New partners help in the exploration of new knowledge (March 1991) and can potentially lead to greater global innovation generation. However, the same partners would bring no new knowledge to the relationship or would have high knowledge redundancy. Given the contradictory predictions of TCA theory and the KBV, we offer the following alternate hypotheses to summarize our theorizing:

-

H6a:

As the diversity of partners increases, global innovation generation increases.

-

H6b:

As the diversity of partners increases, global innovation generation decreases.

Alliance governance and global innovation generation

Vertical alliances versus horizontal alliances and global innovation generation

Vertical alliances refer to alliances with upstream or downstream supply chain partners, and they reduce transaction costs. These partners are not competitors and either buy from or sell to the focal firm. Vertical alliances (as opposed to horizontal alliances) generally involve more interdependence among the firms that may facilitate knowledge transfer and innovation (Roy and Sivakumar, in press). Although several factors determine the nature of interdependence between firms, other things being equal, we argue that vertical alliances exhibit more dependence than horizontal alliance. The marketing or selling side of the firm is focused on expanding its market share in certain market segments and attempts to pitch its offerings to the buying side of its potential customers. In contrast, the focal firm’s purchasing and procurement personnel are at the receiving end of potential suppliers’ new ideas and thus can frequently come up with new ideas themselves. Thus, innovation involves activity at the supply or upstream end of focal firms.

Low knowledge redundancy is important if innovation is to occur (Bower and Christensen 1995; Chandy and Tellis 2000), in line with the KBV. Only when the focal firm is exposed to different knowledge sets can it become aware of the possibilities of creating a dominant design (Anderson and Tushman 1990) or, conversely, miss technological opportunities if there is too much knowledge redundancy (Christensen 1997). Thus, a pharmaceutical R&D lab might collaborate with another lab across borders for conducting assays on some compound it might develop. Zhao and Luo (2005) find that vertical alliances enhance the innovation generation between partners. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

-

H7:

As the proportion of vertical alliances relative to the total number of alliances increases (compared to horizontal alliances), global innovation generation increases.

JVs versus other alliances and global innovation generation

Joint ventures are a special type of alliance in which both partners have an equity stake and their relationship is governed not only by contract but also by ownership and oversight of the JV. Until the 1990s, innovation generation was primarily by way of technology transfer from parent companies to JVs (Inkpen and Beamish 1997; Lyles and Salk 1996), and scholars were concerned with the kind of governance that might facilitate the innovation generation.

With increased globalization (Lyles and Salk 1996), the focus is now on JV alliances in which the innovation generation occurs in both directions. That is, the direction of knowledge flow changed from being one way (from developed to developing countries) to being two way (from developing to developed countries, and vice versa) in the case, for example, of R&D work being outsourced. When the subsidiary company completes the R&D and patents are registered abroad, we expect that the JV form of governance allows for oversight, control, and monitoring for enhanced innovation generation. The JV form of governance allows for the reporting and control of the subsidiary and is particularly conducive to defending and enhancing intellectual property rights. Because of the shared participation and governance mechanisms in JV relationships, as well as the subsequent long-term nature of the relationship, the knowledge transfer between firms is facilitated and therefore results in global innovation generation more so than other contractual arrangements. Stated formally:

-

H8:

As the proportion of JV alliances relative to the total number of alliances increase, global innovation generation increases.

Global innovation generation and financial performance of the focal firm

Thus far, we have developed hypotheses that link the alliance expertise (number of alliances and diversity of partners) and alliance governance (JVs and vertical/horizontal alliances) with the level of firms’ global innovation generation. A key question is whether global innovation generation enhances the level of firms’ financial performance over time and whether there is a shape that can predict this performance. To answer this question, we first consider KBV and the S curves of innovation as they pertain to performance. We then examine the prediction of TCA and its derivative relationship theory on firm performance over time.

Although innovation generation improves performance (Makino and Delios 1996) and shows evidence of increase in financial results (Page 1993), the S curve notion of innovation suggests that when alliance partners work together on the same technological platform, efficiencies increase and costs decrease as knowledge is deployed in practice. Over time, the S curve begins to plateau. That is, no more process improvements are possible on the technology platform. Next, however, a new technology platform is introduced (Anderson and Tushman 1990), and as the focal firm moves to the new S curve, it starts with much higher costs. Sood and Tellis (2005) suggest that the S curve follows a pattern from introduction to growth to maturity. Conceptually, we argue that a successive number of S curves facing a focal firm will result in an inverted U shape of financial performance over time.

Relationship marketing following TCA (Dwyer et al. 1987) suggests that buyer-seller relationships go through the phases of awareness, exploration, expansion, decline, and dissolution, or an inverted U shape. Thus, the alliances we consider herein should follow a similar normal or inverted U-type curve from a performance point of view, ignoring knowledge and innovation consideration. Therefore, on the basis of the relationship marketing enhancement of TCA and considerations of KBV, we hypothesize the following:

-

H9:

Global innovation generation has an inverted U-shaped relationship to financial performance. As global innovation generation increases, financial performance increases up to a point beyond which the financial performance decreases.

Table 1 summarizes the theoretical rationales for the hypotheses.

Methodology

We wanted to test the research hypotheses in an important industry setting that also helps us conduct a focused hypotheses testing. Therefore, we used the pharmaceutical industry to study global innovation generation in the context of strategic alliances. The pharmaceutical industry is also a knowledge-intensive industry (Prabhu et al. 2005; Sorescu et al. 2003) in which alliances have been studied (e.g., Baum et al. 2000; Rothaermel 2001) in the context of biotechnology. The pharmaceutical industry primarily uses patenting in different countries to defend its intellectual property and to prevent competitors from copying products (Cohen et al. 2002). In addition, pharmaceutical firms’ primary motive to patent abroad is to increase income from new markets either by direct marketing or through licensing their patents (Archibugi and Iammarino 2002). Moreover, health care in general and the pharmaceutical industry in particular are considered important sectors of the world economy and that importance is only going to become more prominent in the near future.

Data

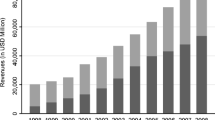

We collected the data on corporate cross-border alliance, global patent registration, and firm financial performance from three different sources that have been used extensively in marketing, finance, and related fields. Because the focus of our study is on cross-border alliances, we began by examining all pharmaceutical firms in Thomson Security Data Corporation’s (SDC) alliance database. This database uses information from the Securities and Exchange Commission filings and its international counterparts, trade publications, and other wire and news sources. The SDC is a comprehensive alliance data source that is most commonly used in empirical studies published in top business and management journals (Schilling 2009). We chose the 1985–2008 period for our study (a 24-year period provides sufficient representation of global alliances).

To obtain data to measure the global innovation generation of the firms under study, we collected information on both the issued U.S. and the global patents for the studied period from the European Patent Office. Finally, we obtained the metrics on the firms’ financial performance from COMPUSTAT, including the focal measure of Tobin’s q and other variables (e.g., sales, R&D expenses).

We limited our data to firms that have frequent occurrence of cross-border alliances (nine or more within the study period; i.e., a minimum of one cross-border alliance every 3 years on average). Collectively, our sample contains 20 publicly traded U.S. firms with a sample size of 353. Each observation is firm-year combination. For example, for Abbott Laboratories, our dataset has 23 observations, one per year, from 1986 to 2008 (we use lag term, and thus the data in our analysis start from 1986 instead of 1985). The Abbott Laboratories-2000 EXPERIENCE variable is the cumulative number of cross-country alliances as of 2000 for the company. Table 2 shows the detailed variable operationalization and data sources. Table 3 displays the summary statistics and the correlations among all key variables.

The global innovation generation model

We consider global patents a proxy for global innovation generation. Ahuja (2000) maintains that patents are an important indicator of inventiveness, and Narin et al. (1987) find that patents are an excellent indicator of technological strength. Although Prabhu et al. (2005) measure innovation in the pharmaceutical industry as the number of phase I products, they use patents as an indicator of knowledge. Mansfield (1986) finds that 80% of patentable innovations in pharmaceuticals are patented. By using patents as a proxy for innovation generation, we extend the industrial notion of innovation generation as adaptation by buyer and seller (Hakansson and Snehota 1989; Roy et al. 2004) to knowledge intensive industries such as pharmaceuticals operating globally. In the industrial age, changes within the technology platform (Tushman and Anderson 1997) that improved efficiency or reduced costs were considered innovations. However, in a global marketplace, knowledge intensive firms file patents not only for radical innovations but also for incremental innovations, to keep competitors at bay. Firms file patents globally when they want to expand their market into foreign countries through a form of alliance that could include horizontal alliances involving technology licensing, JVs, and vertical types of marketing and R&D alliances (Archibugi and Iammarino 2002). In addition, global patents based on R&D alliances speed up the NPD cycle and can effectively tap a larger market to rapidly harvest increasingly shorter product life cycles (Archibugi and Iammarino 2002). A firm could also file a patent in another country to prevent competitors from entering the market and might never actually enter the market itself. Our theorizing of global innovation generation includes all these possibilities and treats globalization of innovation generation as a leading indicator of “staking out” the claim of the focal firm in the foreign market. Although the debate on an appropriate measure of global innovation generation continues, Hagedoorn and Cloodt (2003) provide a comprehensive study that measures innovative performance in 1200 companies in four high-tech sectors using (1) R&D inputs, (2) patent counts, (3) patent citations, and (4) new product announcements. They find that though these four indicators measure a latent variable–innovation performance, there is a strong statistical overlap between the four indicators. The statistical overlap is so strong that Hagedoorn and Cloodt suggest that it is reasonable to measure innovation performance by any of the measures.

Accordingly, we use the extent to which firms attain international patents as an indicator of the cumulative level of globalization of patents or a measure of global innovation generation. Mathematically, the level of global innovation generation can be written as \( {\hbox{GLOBALINNO}}{{\hbox{V}}_{\rm{it}}} = {\hbox{logit}}\left[ {{1} - \left( {{\hbox{HOME PATEN}}{{\hbox{T}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}}/{\hbox{GLOBAL PATEN}}{{\hbox{T}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}}} \right)} \right] \). The term \( {\hbox{HOME PATEN}}{{\hbox{T}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}} \) is the cumulative number of U.S. patent registrations for firm i as of year t, and \( {\hbox{GLOBAL PATEN}}{{\hbox{T}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}} \) is the cumulative number of total patent registrations throughout the world (including the U.S.) for firm i as of year t. The logit transformation maps the original ratio (bounded by 0 and 1) to a real line, which then is appropriate for the use as a dependent variable in regression analysis. The level of alliance experience (EXPERIENCEit) is the number of cumulative inter-firm cross-border partnerships that firm i has formed as of year t.

Following the work of Wuyts et al. (2004), we measure diversity of partners as \( {\hbox{DIVERSIT}}{{\hbox{Y}}_{\rm{it}}} = \left( {{\hbox{NE}}{{\hbox{W}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}}/{\hbox{ALLIANC}}{{\hbox{E}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}}} \right) \), where \( {\hbox{NEW}}_{\rm{it}}^{\rm{cum}} \)is the cumulative number of new partner firms that firm i has had as of year t and \( {\hbox{ALLIANC}}{{\hbox{E}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}} \) is the cumulative number of all alliances that firm i has had as of year t. Therefore, the more new partners a firm has, the higher is the level of diversity. In accordance with Gulati (1995), we measure vertical alliances as \( {\hbox{VERTICA}}{{\hbox{L}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}}/{\hbox{ALLIANC}}{{\hbox{E}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}} \), where \( {\hbox{VERTICA}}{{\hbox{L}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}} \) is the cumulative number of vertical collaborative projects that firm i has formed as of year t. Vertical alliances are concluded between firms in different Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes. The term JVit is the ratio of the cumulative number of JVs that firm i has formed as of year t. It is measured as \( {\hbox{J}}{{\hbox{V}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}}/{\hbox{ALLIANC}}{{\hbox{E}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}} \), where \( {\hbox{J}}{{\hbox{V}}_{\rm{it}}}^{\rm{cum}} \) is the cumulative number of JVs that firm i has formed as of year t.

To control for variables that may affect global innovation generation and financial performance of the focal firms, we include variables for firm size (SIZEit) and R&D intensity (R&Dit). The operationalization of the two variables are, respectively, log of sales of firm i at year t (Wright et al. 2002) and the ratio of R&D expenses to total sales of firm i at year t (Das and Teng 2000; Luo and Homburg 2007; Luo et al. 2010).

The financial performance model

We use Tobin’s q (Q) as a measure of firm performance. Tobin’s q has been used in marketing research to measure the financial impacts of variables such as brand equity (Simon and Sullivan 1993), customer satisfaction (Anderson et al. 2004), and strategic responses to new technologies (Lee and Grewal 2004). We define Qit as the ratio of firm i’s market value at year t to its replacement cost at year t, and it can be written mathematically as (market value of the firm’s common stock shares + book value of the firm’s preferred stocks + book value of the firm’s long-term debt + book value of the firm’s inventories + book value of the firm’s current liabilities–book value of the firm’s current assets)/(book value of the firm’s total assets) (Chung and Pruitt 1994; Morgan and Rego 2006, 2009). Thus, a higher value of Tobin’s q indicates the higher value of a firm’s relative financial value adjusted by its asset size. Tobin’s q serves as an important measure of a firm’s market value in terms of forward-looking stock market performance (Luo and Donthu 2006). We made a log transformation for the raw Tobin’s q value to map the positive ratio to a real line before using it as a dependent variable in regression analysis. We input GLOBALINNOV and its quadratic term to study the effect of diminishing return (inverted U shape) of global innovation generation on Tobin’s q. Alliance characteristics enter the equation to demonstrate their net/direct contribution to financial performance beyond the indirect effect through global innovation generation. We also control for variables in the financial performance model that are known to affect Tobin’s q, by including firm size (SIZEit) and R&D intensity (R&Dit).

Model specification

From the previous discussion, we can write the two estimated models as follows:

and

By definition, the GLOBALINNOV and Tobin’s q measures are likely to be correlated over time (Corr[Qit, Qit–1] = 0.73, p < 0.001; Corr[GLOBALINNOVit, GLOBALINOVit–1] = 0.89, p < 0.001). The autoregressive model with one time lag—that is, the AR(1) model run with key independent variables (without the lag terms of the dependent variable)—showed autocorrelation of the residual from the regression. For the global innovation generation equation, the estimated rho is 0.85 (p < 0.001) with a Durbin–Watson statistic of 0.25. For the Tobin’s q equation, the estimated rho is 0.80 (p < 0.001) with a Durbin–Watson statistic of 0.44. To account for the autocorrelation, we include a lag term of the dependent variable in both equations in our time-series formulation. The inclusion of past firm financial performance enhances the prediction for current financial performance while solving the issue of autocorrelation (Dechow et al. 1998; Gruca and Rego 2005).

The inclusion of the year dummy YDij (j = 1, 2,..., 22) in the Tobin’s q equation serves two important purposes: to obtain estimates free from the effect of time and to control for unobserved heterogeneity before pooling the data. First, these year dummies teased out the effect of time on the dependent measures potentially incorporated in our study variables. Some focal variables are correlated with ordinal time (time = 1 for 1986, 2 for 1987, and so on; corr[EXPERIENCE, time] = 0.55, p < 0.001; corr[DIVERSITY, time] = 0.23, p < 0.001; corr[VERTICAL, time] = 0.20, p < 0.001). Therefore, because EXPERIENCE is partially a function of time, by including the time variable, our estimated effects of the focal variables are free from the time effects. The inclusion of year dummies controls both the linear and non-linear time effects in the model and purifies the estimated results for our study variables. It improves the model fitting significantly with the likelihood ratio test statistic of \( \chi_{{\rm{df}} = {22}}^2 = {166}.{6}0 \), p < 0.001.

Second, the inclusion of year dummies captures the unobserved year-specific effects (see Arellano 2003; Boulding 1990; Boulding and Christen 2003), which makes our data poolable in the analysis. The likelihood ratio test shows that after we include the year dummy variables, there is no significant improvement in model fit to further include firm indicators in capturing baseline (intercept) heterogeneity across firms (\( \chi_{{\rm{df}} = {19}}^2 = {18}.{4}0 \), p = 0.496). Similarly, there is no need for the coefficients of our study variables (other than the intercept and year dummies) to vary further across time or over firms to capture potential unobserved heterogeneity. The likelihood ratio tests show insignificant improvement for the model fitting for the random time effects model (\( \chi_{{\rm{df}} = {9}}^2 = {3}.{1}0 \), p = 0.960) and random firm effects model (\( \chi_{{\rm{df}} = {9}}^2 = 0.{3}0 \), p = 1.000) after we include the year dummies in adjusting the baseline time effects. In summary, after we include the year dummies, there are no estimation issues related to unobserved heterogeneity across time and over firms.

For the global innovation generation equation, the likelihood ratio tests show that there is no need to include year dummies (\( \chi_{{\rm{df}} = {22}}^2 = {29}.00 \), p = 0.145) or firm indicators (\( \chi_{{\rm{df}} = {19}}^2 = {14}.{40} \), p = 0.760). The Hausman test is also in favor of a fixed-effects model over a random-effects model (random time effect model; \( \chi_{{\rm{df}} = {7}}^2 = {1}5.{93} \), p = 0.026; random firm effects model: \( \chi_{{\rm{df}} = {7}}^2 = {14}.{65} \), p = 0.041). Therefore, we do not include year dummy, firm indicator, or any form of random effect in this equation, and it is appropriate to pool the data for study.

In our model, all key independent variables—namely, GLOBALINNOV (in the Tobin’s q equation only), EXPERIENCE, DIVERSITY, VERTICAL, and JV—are measures of the same year as the dependent variables. In addition, the model captures two longitudinal effects. The independent variables have a contemporary and direct effect on the dependent measures of the same year. Equally important, they also have a lagged and indirect impact on dependent measures for future years through the lag structure in the model (i.e., the lag term of the dependent variable in each equation). For example, global innovation generation is modeled as having timely impact on firm financial performance of the same period. Furthermore, our model allows for an effect on firms’ financial performance for the subsequent years as well (Deng et al. 1999) because of the stickiness captured with the lag term of Tobin’s q. This lag term serves as an inertia and amplifier effect in the model, which carries the current year’s effect of global innovation generation to future periods. This modeling of lag structure reflects the belief that it takes time to fully commercialize patent output from an alliance. Current global innovation generation is determined by both current and past alliance characteristics. By the same token, it takes time to completely materialize global innovation generation and alliance in firm performance. Current Tobin’s q is determined by both current and past global innovation generation and alliance characteristics. The coefficients for both the lag term and the key independent variables jointly decide the magnitude of the lag effects of the key variables under study.

Two-stage least squares estimation

To account for the dual role of GLOBALINNOV as both a dependent variable and a predictor in the two-equation analysis, we must estimate these two equations simultaneously. We performed a Hausman test (Greene 2003; Hausman 1978) and validated the endogeneity of the predictors GLOBALINNOVit and (GLOBALINNOVit)2 in the model with a chi-square statistic of 6.29 (df = 2, p = 0.043). Therefore, we used the two-stage least squares approach to estimate the simultaneous equation system while correcting the endogeneity problem (Greene 2003; Gujarati 2004; Wooldridge 2001).

The control variable SIZE is correlated highly with the key variables under study (e.g., Corr[EXPERIENCE, SIZE] = 0.40, p < 0.001; Corr[DIVERSITY, SIZE] = 0.10, p = 0.065; Corr[JV, SIZE] = 0.43, p < 0.001). To account for this, we regressed SIZE on all four key alliance variables (i.e., EXPERIENCE, DIVERSITY, VERTICAL, and JV) and then entered the residual from this regression as the SIZE variable. This orthogonalization guarantees the independence of SIZE with the key variables in the model while maintaining the model’s explanatory power (e.g., Morgan and Rego 2009). It also makes good managerial sense because the new SIZE variable captures the true operational size of the firm (sales) net of the effects of the alliance.

Other methodological details

In order to increase the methodological rigor and robustness of our study, we adopted a number of methodological steps. In the interest of space, we just briefly discuss some these procedures without providing additional details.

Due to the high correlation between some alliance characteristics and time, a concern is whether time might be the underlying driver for the dependant measures, permeating through the key variables in the model. To address this concern, we compared models with and without time/year information in different formats, such as ordinal variables and dummy indicators. Based on the results, we included time information as year dummies in the Tobin’s q equation to best account for the effect of time. As to time lags, we tried different lag period between predictors (0–3 years) and Tobin’s q and find that the results are consistent across different options. Moreover, the 1-year lag choice provides us with the best model fitting and interpretation.

Analysis using alternative variables for Tobin’s q

Despite its widespread use, Tobin’s q as a financial measure has certain limitations, such as the random-walk contamination of the measure, the stationarity of the measure, and the difficulty in computation of intangible assets (Mizik and Jacobson 2009; Srinivasan and Hanssens 2009). However, no single measure can be perfect without any limitation. In validating our findings on global innovation generation’s effect on firm financial performance, we ran similar models on two other commonly used financial metrics—namely, price-to-book ratio and cash flow from operations—which measure firm financial performance from different perspectives (Gruca and Rego 2005; Srinivasan and Hanssens 2009). Price-to-book ratio, which is measured as the ratio of market value to the book value of common equity, is a forward-looking measure of a firm’s market value, providing market-based views of investor expectations of the firm’s future profit potential (Srinivasan and Hanssens 2009). Net present value of future cash flow has long been proposed as the value of a firm to shareholders (Rappaport 1986) because marketing scholars treated future cash flow as an appropriate measure of shareholder value (Srivastava et al. 1998, 1999). These follow-up studies serve as a robustness check to validate our findings of the effects of global innovation generation on firm financial performance and shareholder value. The results are consistent with the results using Tobin’s q and not presented in the article in the interest of space.

Results

Table 4 presents the parameter estimation results for the global innovation generation and financial performance models. To verify H1–H4, we compute the total effect of the alliance characteristics on financial performance using two components: (1) a direct effect as manifested by the coefficients in the financial performance model and (2) an indirect effect as manifested by both the coefficients in the global innovation generation model and the coefficients of the global innovation generation variables in the financial performance model.

The total effect of target variable X (which can be EXPERIENCE, DIVERSITY, ALLIANCE, or JV) can be calculated as a partial derivative of Tobin’s q. That is:

where β gX and β qX are coefficients of variable X in the GLOBALINNOV and Tobin’s q equation, respectively. In addition, β q2 and β q3 are coefficients for GLOBALINNOV and (GLOBALINNOV)2 from the Tobin’s q equation, respectively.

From this equation, we know that the total effect of alliance characteristics on Tobin’s q is non-linear and varies with the value of GLOBALINNOV. We conduct a sensitivity analysis and summarize the findings in Table 5. Alliance experience and JV have a positive total effect on Tobin’s q when the level of global innovation generation is low or medium. However, the positive effect weakens as the level of global innovation generation increases. With high levels of global innovation generation, the effect becomes negative. Therefore, H1 and H4 are supported for low to moderate levels of global innovation generation (which is a majority of our sample). Diversity shows the reversed pattern; it has a total negative effect on Tobin’s q when the level of global innovation generation is low or medium. However, the negative effect weakens as the level of global innovation generation increases, and it becomes positive when the level of global innovation generation is high. Thus, H2 is supported at high levels of global innovation generation. Given the lack of statistical significance of VERTICAL in both models, vertical alliance has no significant impact on Tobin’s q. Therefore, H3 is not supported.

In the global innovation generation equation, global innovation generation from the last period has a positive impact on the current year’s global innovation generation, which validates the previous finding of autocorrelation (β = .702, p < .001). The results show that alliance experience positively influences the level of global innovation generation (β = .005, p = .007), in support of H5. Note that for the role of partner diversity on global innovation generation, we offered a two-part hypothesis with contradictory predictions because of the differences in predictions of the two theoretical perspectives. The level of partner diversity shows a negative impact on global innovation generation (β = −.523, p < .001). Thus, the results are consistent with H6b but not with H6a. H7 is not supported, which maintains that vertical collaboration enhances the level of global innovation generation (β = −.101, p = .347); H8 is supported because the number of JVs are positively related to global innovation generation (β = .647, p < .001). For the control variables, both firm size (β = .086, p < .001) and R&D intensity (β = .389, p < .001) positively influence global innovation generation.

For the financial performance model, Tobin’s q of the last year positively influences the current year’s Tobin’s q, which is consistent with our previous finding of autocorrelation (β = .764, p < .001). The main effect of the level of global innovation generation on financial performance is significantly positive (β = .080, p = .034), but its quadratic effect is significantly negative (β = −.013, p = .049). The results suggest that there is an inverted U-shape relationship between the level of global innovation generation and firms’ financial performance, providing support for H9. Alliance experience, diversity, vertical collaboration, and JVs do not have a significant direct impact on financial performance, because the estimates are all insignificant.

Discussion

In this section, we highlight the meaning and implications of our findings for the conceptual understanding of business-to-business alliances in cross-border settings. We also delineate our study’s insights for managerial practice as well as future research directions.

Theoretical implications

This research has several theoretical and substantive implications for understanding inter-firm alliances, global innovation generation, and financial performance. First, our conceptualization incorporates the notion that innovation generation in business-to-business relationships is an important phenomenon that has a direct impact on the financial well-being of the firm. Our argument also shows that multiple theoretical frameworks help inform the linkages among alliance characteristics, innovation generation, and financial performance. By incorporating multiple theoretical frameworks, we tried to explore and shed some light on the “why” and “how” of these linkages.

Second, this study contributes to research in the domain of the KBV of the firm. Because innovation generation is primarily a knowledge-based process, we shed more light on the relationship between alliance characteristics and cross-border knowledge transfer, the success of which manifests in global innovation generation in general and globalization of patents in particular. The findings show that the value of a firm increases with the level of global innovation generation up to a point; after that, the relationship becomes negative. Therefore, the study provides empirical support for the notion that innovation generation and firm growth are highly inter-linked (Kogut and Zander 1993) but cautions that too much global innovation generation may not be good for financial performance of the focal firm.

Third, the study contributes to the alliance literature in business-to-business relationships. Recent work has suggested that alliances weakly contribute to firms’ financial value (Gupta and Mirsa 2000). In contrast global innovation generation could be the missing link between alliance and financial performance because our study shows that the influence of alliance governance on firm financial performance exists mainly indirectly through innovation generation. Thus, our finding provides important insights into the manifestation of alliance characteristics on innovation generation and financial performance.

Though theoretically predicted, we note the insignificant results for the type of alliances (vertical vs. horizontal) on both the equations (hypothesis H7). Although further research in other industries and other settings (e.g., domestic alliances) may shed more light on the phenomenon, an explanation for these results is that in the case of pharmaceutical industry, some of the vertical alliances may involve very diverse industries (medical device vs. drug formulation) that may mask the interdependence in business relationships.

Managerial implications

This study also contributes to managerial practice by offering some useful insights for managers involved in the management of cross-border alliances. The findings suggest that alliances are an important driver of innovation generation and that inter-firm alliances play a crucial role in firm financial performance. However, the findings also show that innovation generation is not easy to manage; therefore, managers must recognize that knowledge transfer needs to be strategically planned and properly leveraged to yield superior financial performance (Zhao and Luo 2005). This research finds that firms must actively develop alliance expertise and alliance governance to increase innovation generation and the underlying knowledge transfer. Innovation generation is an important variable for firm financial performance.

Similarly, managers must realize that the characteristics of alliance partners should be considered holistically, in which the number of alliances and the diverse partnering at the firm level are considered simultaneously. Selection of an alliance partner can no longer be based on consideration of an individual firm as a potential partner; the mix of partners and agreement types must be carefully managed. The type of partnering is also an important variable of this research. Firms should attempt to have a greater mix of JV-type partnerships, which in turn should lead to greater innovation generation.

The second-stage results of our model suggest that global innovation generation is good for financial performance of the focal firm up to a point, but increased innovation generation might be counterproductive to financial performance beyond that point. Therefore, managers should balance the need for global patents with the availability of alliance partners that can execute the firm’s mission. In addition, equity JVs enhance firm financial performance only through innovation generation. This result underscores the importance of a careful deployment of alliance outcomes that are related to alliance characteristics. In addition, the importance of the strategic thrust of the focal firm may vary during its life cycle, and thus to optimize financial performance, managers must carefully align the firm strategic objectives with the alliance characteristics to result in the desired level of global innovation generation.

Directions for further research

Our conceptual framework and empirical analysis are intended to offer an expanded view of innovation generation in business-to-business alliances. The findings also suggest avenues for further research in this exciting domain. Our findings clearly show that global innovation generation is an important mediating variable that links alliance characteristics and financial performance. This finding leads to an important future research question regarding whether other mediating factors affecting financial outcomes of alliance exist. Findings from such research would lead to a better understanding of the impact of alliances on firm financial performance.

We previously noted how the characteristics of the pharmaceutical industry are relevant in explaining some of the findings. We deliberately restricted our analysis to one industry because we wanted to focus on a knowledge-based industry and did not want our analysis to be confounded by industry differences. Further research should try to tease out the potential differences between the type of alliances (e.g., marketing vs. R&D alliances, R&D vs. manufacturing alliances) to understand the role of these relationships in a more fine-tuned way. Examining inter-industry differences will be an important next step in this research domain.

Although patents are a reasonable measure of innovation generation, there are a few limitations of the measure. For example, patents may sometimes underestimate the true innovative capacity of the firm because some inventions cannot be patented, and firms may not patent some inventions for strategic reasons (Cohen and Levin 1988; Griliches 1990). More comprehensive measures must be developed for innovation generation as research progresses in this domain. Among the candidates are R&D inputs, patent citations, and new product announcements. They, together with patent counts, measure the innovative performance from different angles, but show a strong statistical overlap with the latent construct of innovative performance (Hagedoorn and Cloodt 2003).

An important research extension worth exploring for managerial insights is the relative importance of various alliance characteristics in influencing global innovation generation and financial performance and how this relationship changes over time and across industries. Such fine-tuned analysis would further help managers in structuring suitable cross-border alliances over the life cycle of the firm. Using qualitative research (e.g., organizational ethnography, case studies), researchers could also examine the locus and development of cross-border alliances during the evolution of the focal firm’s globalization and its impact on financial performance.

We focused on linking the alliance characteristics of the focal firm with the aggregate level of global innovation generation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on alliance characteristics and globalization of patents at the aggregate level for the firm’s activities. The next level of fine-grained analysis could focus on individual country combinations as the unit of analysis and use that combination to examine the joint patents as well as inter-country alliances. Such an analysis would require more detailed datasets.

Finally, further research might explore the role of cross-border alliances in industries that are characterized by different levels of market and/or technological turbulence. On the one hand, cross-border alliances bring new institutional knowledge, routines, and culture to face new market demands; on the other hand, management of these alliances and resultant organizational transformations may take significant leadership and managerial resources to establish, develop, and monitor those alliances. These research issues must be addressed from an inter-disciplinary perspective because disciplines such as marketing, management, and information technology are all relevant in examining the topics in turbulent environments.

Conclusion

We believe that in this age of increased global relationships among firms and the advent of technology, inter-firm relationships in knowledge-based tasks will become more important in deciding the competitive advantage and financial performance of firms. A fine-tuned understanding of the relationships among alliance expertise, alliance governance, global innovation generation, and financial performance and the ability of the firms to manage these alliances will become increasingly more important in the future.

References

Achrol, R. S. (1991). Evolution of the marketing organization: new forms for dynamic environments. Journal of Marketing, 55, 77–93.

Ahuja, G. (2000). Collaboration networks, structural holes, and innovation: a longitudinal study. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(3), 425–455.

Almeida, P., & Kogut, B. (1997). The exploration of technological diversity and geographic localization of innovation. Small Business Economics, 9(1), 21–31.

Almeida, P., Song, J., & Grant, R. M. (2002). Are firms superior to alliances and markets? an empirical test of cross-border knowledge building. Organization Science, 13(2), 147–161.

Anand, B., & Khanna, T. (2000). Do firms learn to create value? The case of alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 295–315.

Anderson, P., & Tushman, M. L. (1990). Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: a cyclical model of technological change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(4), 604–634.

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Mazvancheryl, S. K. (2004). Customer satisfaction and shareholder value. Journal of Marketing, 68, 172–185.

Archibugi, D., & Iammarino, S. (2002). The globalization of technological innovation: definition and evidence. Review of International Political Economy, 9(1), 98–122.

Arellano, M. (2003). Panel data econometrics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baum, J. A. C., Calabrese, T., & Silverman, B. S. (2000). Don’t go it alone: alliance network composition and startups’ performance in Canadian biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal: Special Issue: Strategic Networks, 21(3), 267–294.

Bhagat, R. S., Kedia, B. L., Harveston, P. D., & Triandis, H. C. (2002). Cultural variations in the cross-border transfer of organizational knowledge: an integrative framework. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 204–221.

Boulding, W. (1990). Commentary on ‘Unobservable effects and business performance: do fixed effects really matter?’. Marketing Science, 9(4), 88–91.

Boulding, W., & Christen, M. (2003). Sustainable pioneering advantage? profit implications of market entry order. Marketing Science, 22(3), 371–392.

Bower, J. L., & Christensen, C. M. (1995). Disruptive technologies: catching the wave. Harvard Business Review, 73, 43–53.

Boyd, D., & Spekman, R. (2008). The market value impact of indirect ties within technology alliances. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(4), 488–500.

Buckley, P., & Casson, M. (1976). The future of multinational enterprise. London: Macmillan.

Capron, L. (1999). The long-Term performance of horizontal acquisitions. Strategic Management Journal, 20(11), 987–1018.

Capron, L., & Hulland, J. (1999). Redeployment of brands, sales forces, and general marketing management expertise following horizontal acquisitions: a resource-based view. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 41–54.

Chandy, R. K. (2003). Research as innovation: rewards, perils, and guideposts for research and reviews in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(3), 351–355.

Chandy, R. K., & Tellis, G. J. (2000). The incumbent’s curse? incumbency, size, and radical product innovation. Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 1–17.

Christensen, C. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press.

Christopher, M. (2000). The agile supply chain competing in volatile markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(1), 37–44.

Chung, K. H., & Pruitt S. W. (1994). A simple approximation of Tobin’s Q. Financial Management, (Autumn), 70 –74.

Clark, K. B., & Fujimoto, T. (1991). The process of development: From concept to market. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4, 396–405.

Cohen, W. M., & Levin, R. C. (1988). Empirical studies of innovation and market structure. In R. Schmalensee & R. Willig (Eds.), The North-Holland handbook of industrial organization. New York: North-Holland.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152.

Cohen, W. M., Nelson, R. R., & Walsh, J. P. (2002). Links and impacts: the influence of public research on industrial R&D. Management Science, 48(1), 1–23.

Contractor, F. J., & Lorange, P. (2002). The growth of alliances in the knowledge-based economy. International Business Review, 11(4), 485–502.

Corcoran, E. (2004). Unoutsourcing. Forbes, 173(10), 50.

Dahlstrom, R., McNeilly, K. M., & Speh, T. W. (1996). Buyer-seller relationships in the procurement of logistical services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24(2), 110–124.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (2000). A resource based theory of strategic alliances. Journal of Management, 26(1), 31–61.

Day, G. S. (1992). Marketing’s contribution to the strategy dialogue. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 20(4), 331–334.

Dechow, P. M., Kothari, S. P., & Watts, R. L. (1998). The relation between earnings and cash flows. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 25(2), 133–168.

Deeds, D. L., & Hill, C. W. L. (1996). Strategic alliances and the rate of new product development: an empirical study of entrepreneurial biotechnology firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(1), 41–55.

Deng, Z., Lev, B., & Narin, F. (1999). Science and technology as predictors of stock performance. Financial Analysts Journal, 55(3), 20–32.

Dhanaraj, C., Lyles, M. A., Steensma, H. K., & Tihanyi, L. (2004). Managing tacit and explicit knowledge transfer in IJVs: the role of relational embeddedness and the impact on performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 428–442.

Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27.

Dyer, J. H. (1996). Specialized supplier networks as a source of competitive advantage: evidence from the auto industry. Strategic Management Journal, 17(4), 271–292.

Ekeledo, I., & Sivakumar, K. (1998). Foreign market entry mode choice of service firms: a contingency perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(4), 274–292.

Fang, E., Palmatier, R. W., Scheer, L. K., & Li, N. (2008). Trust at different organizational levels. Journal of Marketing, 72(2), 80–98.

Friedman, T. L. (2005). The world is flat. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Fryxell, G. E., Dooley, R. S., & Vryza, M. (2002). After the ink dries: the interaction of trust and control in US-based international joint ventures. Journal of Management Studies, 39, 865–886.

Gadde, L. E. (2004). Activity coordination and resource combining in distribution networks: implications for relationship involvement and the relationship atmosphere. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(1 –2), 157–184.

Ghosh, M., & John, G. (2005). Strategic fit in industrial alliances: an empirical test of governance value analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(3), 346–357.

Gilbert, R. J., & Newbery, D. M. G. (1982). Preemptive patenting and the persistence of monopoly. The American Economic Review, 72, 514–526.

Gimeno, J. (2004). Competition within and between networks: the contingent effect of competitive embeddedness on alliance formation. Academy of Management Journal, 47(6), 820–842.

Grant, R. M., & Badden-Fuller, C. (1995). A knowledge -based theory of inter-firm collaboration. In [editors], (Eds), Proceedings of the Academy of Management, pp. 17–21.

Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Griliches, Z. (1990). Patent statistics as economic indicator: a survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 28, 1661–1707.