Abstract

The management of ischaemic stroke survivors is multidisciplinary, necessitating the collaboration of numerous medical professionals and rehabilitation specialists. However, due to the lack of comprehensive and holistic follow-up, their post-discharge management may be suboptimal. Achieving this holistic, patient-centred follow-up requires coordination and interaction of subspecialties, which general practitioners can provide as the first point of contact in healthcare systems. This approach can improve the management of stroke survivors by preventing recurrent stroke through an integrated post-stroke care, including appropriate Antithrombotic therapy, assisting them to have a Better functional and physiological status, early recognition and intervention of Comorbidities, and lifestyles. For such work to succeed, close interdisciplinary collaboration between primary care physicians and other medical specialists is required in a holistic or integrated way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

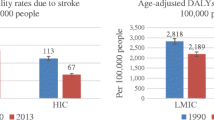

Ischaemic stroke is a major cause of long-term disability worldwide [1]. Advance in the medical management of stroke reduced stroke mortality and increased the number of people discharged home after a stroke [2]. For stroke survivors and their families, hospital discharge is just the beginning of a long journey. Many stroke survivors experience recurrent cerebrovascular events or complications within months or years of their initial event [3]. Management of complications and prevention of recurrent stroke necessitates a multidisciplinary approach from various healthcare providers, including stroke specialists, general practitioners, cardiologists, internists, radiologists, speech and rehabilitation specialists, and psychologists. All these experts should share goals and objectives following a common post-stroke integrated care plan to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Due to a lack of holistic follow-up, stroke survivors and their caregivers may feel abandoned. Since general practitioners (GPs) are the first point of contact with the healthcare system in many countries, they are in an ideal position to coordinate subspecialties to optimise chronic disease management, including complications and comorbidities. They play an important role in secondary prevention after stroke by controlling clinical risk factors and optimising overall management.

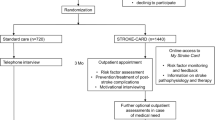

Multiple pieces of evidence and speciality guidelines guide primary care physicians in the complex management of people with a previous stroke. This review summarises this literature and highlights strategies for preventing recurrent stroke, maximising function, and identifying and managing complications. This broadly follows the post-stroke ABC pathway approach, recently recommended in a position paper from the European Society of Cardiology Council on Stroke [4]: A for Appropriate antithrombotic therapy, B for Better functional and psychological status, and C for Comorbidities and lifestyle, patient values and preferences (Fig. 1).

Management of post-stroke patients based on ABC pathway approach. TIA transients ischemic attack, ESUS embolic stroke of undetermined source, VKA vitamin-K antagonists, INR international normalised ratio, DOAC direct-acting oral anticoagulant, LAA left atrial appendage, AF atrial fibrillation, OAC oral anticoagulant, PFO patent foramen ovale

A move to an integrated care pathway approach has been advocated for many long-term conditions [5]. In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), for example, adherence to an integrated care pathway has been associated with improved clinical outcomes, leading to its recommendation in international guidelines. [6, 7]

[A]ppropriate antithrombotic therapy

Antithrombotic therapy is the backbone of secondary stroke prevention based on the underlying potential stroke aetiology and the individualised indications or contraindications. It is an essential component of an integrated care pathway for stroke management.

Antiplatelet therapy

Antiplatelet therapy is the standard antithrombotic strategy in most patients with non-cardioembolic ischaemic strokes. Current guidelines suggest long-term antithrombotic therapy with a single antiplatelet agent, either low-dose aspirin or clopidogrel, as standard [8, 9]. The combination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole is still recommended in secondary stroke prevention by current AHA/ASA (American Heart Association/American Stroke Association) guidelines [8]. However, the Royal College of Physicians’ guidelines recommends a combination of aspirin and dipyridamole only in patients who cannot tolerate clopidogrel.

However, this combination may be more difficult to tolerate, with a higher discontinuation rate than clopidogrel [10]. Ticagrelor is a new potent P2Y12 inhibitor. Although it may have a role in secondary stroke prevention, especially in patients with large artery intracranial atherosclerosis and after recurrent events [11] the evidence of its effectiveness and safety is limited and should be initiated by secondary care [8]. The role of cilostazol in patients with a previous stroke as monotherapy or in addition to aspirin or clopidogrel has been investigated in RCTs, providing promising results, but these studies only aimed Asian population, thus limiting their generalizability [12, 13].

Although long-term dual antiplatelet with aspirin and clopidogrel is contraindicated in patients with ischaemic stroke due to the increased risk of major bleeding [14], in patients with minor stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] ≤ 3) or a high-risk transient ischaemic attack (ABCD2 ≥ 4), the use of dual-antiplatelet therapy for 21 days is effective and safe [15, 16]. After the first 3-week period, the risk of major bleeding significantly increases. Thus the use of dual antiplatelets for up to 90 days is not universally recommended [15]. The THALES study in patients with mild stroke (NIHSS ≤ 5) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 ≥ 6) showed that the combination of ticagrelor and aspirin had a lower risk of composite stroke or death within 30 days than aspirin monotherapy at the cost of increased risk of severe bleeding [17]. Subgroup analysis of the THALES study revealed that the combination therapy was only beneficial in patients with 30% or greater large artery stenosis, which was not associated with an increased risk of bleeding [11]. The CHANCE-2 trial demonstrated that compared to clopidogrel plus aspirin, the combination of ticagrelor and aspirin modestly lowered the risk of stroke at 90 days in patients with minor ischaemic stroke or TIA who were carriers of CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles, but with more bleeding events [18]. Given the limitations, initiation of such treatments should be initiated by secondary care for selected patients.

Despite an extensive diagnostic work-up for acute ischaemic stroke, the cause of stroke remains unexplained in 20% of patients (i.e. cryptogenic stroke) [19]. The term embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) was introduced to reclassify these patients identifying those who may benefit more from oral anticoagulation [19]. Two large RCTs, the NAVIGATE ESUS (Rivaroxaban Versus Aspirin in Secondary Prevention of Stroke and Prevention of Systemic Embolism in Patients With Recent Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) and RE-SPECT ESUS (Dabigatran Etexilate for Secondary Stroke Prevention in Patients With Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) showed that anticoagulation with rivaroxaban and dabigatran was not superior to aspirin for secondary stroke prevention in unstratified patients with ESUS [20, 21]. Thus, patients who fall into the category of ESUS should be treated with antiplatelet therapy.

Patients with patent foramen ovale (PFO) are at risk of stroke due to venous thromboembolism. PFO-related stroke is more common in people with migraines. Patients with PFO should be treated with PFO closure and/or antiplatelet therapy since anticoagulation is neither more effective nor safer than antiplatelets [22].

A recurrent stroke may occur despite the recommended antithrombotic therapy. Such patients should be investigated for other stroke causes, especially to identify occult AF [23]. If AF or other cause suggesting the use of anticoagulation is not present, patients with recurrent stroke can be switched to another antiplatelet regimen [24]. Ensuring good treatment adherence is particularly important in such cases. Even though short atrial high rate episodes may significantly increase the risk of stroke [25], it is unclear whether stroke patients with short atrial runs would benefit from using oral anticoagulants to reduce their risk of stroke [26]. The increasing use of cardiac implantable devices, external monitors and smart watches provides an opportunity for prolonged rhythm to assess the AF burden for stroke survivors and optimise antithrombotic treatment. The importance of detection of AF is evident, especially when even asymptomatic AF episodes carry a poor prognosis, and more prolonged or sophisticated monitoring approaches can help improve the detection of AF [27].

Anticoagulation therapy

Oral anticoagulation (OAC) is the treatment of choice for the prevention of thromboembolic events and especially ischaemic stroke. OACs include vitamin-K anticoagulants (VKA) and non-vitamin-K oral anticoagulants (NOAC), which are as effective as and safer than VKAs [28]. In patients with previous ischaemic stroke, NOACs significantly reduce the risk of stroke or systemic embolism, haemorrhagic stroke, and major bleeding compared to VKAs [29].

Stroke survivors with AF and stable atherosclerotic disease (i.e. coronary artery disease, carotid disease, peripheral artery disease) should receive OAC monotherapy [30]. Recently, among 2236 patients with stable coronary artery disease, rivaroxaban monotherapy was non-inferior to a combination of rivaroxaban and antiplatelet treatment for the composite outcome of stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, or death from any cause (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.95; P < 0.001 for noninferiority). Also, it was associated with a lower risk of major bleeding (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.89; P = 0.01 for superiority) [31]. Combination therapy can be considered in patients with AF presenting with acute coronary syndromes, especially when undergoing coronary stenting, when it may reduce the possibility of stent thrombosis [32]. In these patients, the duration of triple antithrombotic therapy may vary from 1 to 6 months, balancing the risk of stent thrombosis and bleeding, with dual antithrombotic typically continued for no more than 1 year and followed by OAC alone [32].

Apart from AF, anticoagulation therapy in secondary stroke prevention may be considered with caution in other situations. In patients with a mechanical valve, irrespective of AF, dabigatran was associated with increased thromboembolic risk and bleeding complications compared with warfarin [33]. Thus, NOACs are contraindicated in patients with mechanical valves. Recent data suggest that in patients with AF and a bioprosthetic mitral valve placed more than 3 months previously, rivaroxaban was non-inferior to VKA [34]. These data point towards the use of NOACs also in patients with bioprosthetic valves.

Finally, it is common for patients with AF to have concomitant atherosclerotic disease related to multiple cardiovascular risk factors [35]. The presence of high-grade carotid stenosis in patients with stroke has therapeutic implications for other aspects of secondary prevention such as high-intensity lipid-lowering treatment or carotid revascularisation interventions [36, 37].

Overall, the selection of different antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies for preventing secondary stroke relies on the stroke aetiology, bleeding risk profile, compliance, tolerance to the treatment and potentially, drug resistance (defined as treatment failure or by laboratory tests). Before commencing an antiplatelet/anticoagulant treatment doctors should carefully consider the relative benefits and bleeding risks for each patient. Further research is needed to clarify optimal duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy in patients with symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis since the benefits are primarily seen short-term while the bleeding risk is high throughout the prolonged therapy. Currently, there is inadequate evidence to advocate genetic testing as a standard of care and RCTs are required to assess CYP2C19 gene testing-based antiplatelet therapy for stroke prevention.

[B]etter functional and psychological status

Improvements in the medical management of stroke patients led to a considerable reduction in post-stroke morbidity and mortality. Despite the expanding interventions in secondary stroke prevention, many stroke patients suffer from significant disabilities, resulting in impaired quality of life [2]. Early recognition of patients who benefit more from intense rehabilitation programmes may result in better functional outcomes [38]. Therefore, to provide holistic post-stroke care and achieve the best functional recovery in stroke patients, an integrated care system must incorporate a network between stroke physicians, GPs and rehabilitation teams. Several medical societies provide recommendations to guide post-stroke rehabilitation interventions, including speech and language therapy by early community stroke team and orthoptist input on vision and spasticity management; however, these recommendations may vary according to guidelines and countries [39]. Therefore, they should be tailored to each patient.

Due to moderate to severe disability, stroke survivors need assistance, and family caregivers are the key to taking care of stroke patients. Primary care plays a vital role in the long-term care of stroke survivors, with effective follow-up and information supply and facilitating transfer back to specialist services if required. Training caregivers in basic skills of moving and handling, facilitation of activities of daily living, and simple nursing tasks reduces the burden of care and improves the quality of life of patients and caregivers [40]. Caregiver training has the additional advantages of reducing the costs of stroke care and improving patients’ quality of life. Also, it helps patients to gain independence at an earlier stage [40]. However, due to a lack of holistic follow-up, stroke survivors and their caregivers may feel abandoned.

Depression is a major cause of loss of independence after stroke; within a year after stroke, a third of survivors experience post-stroke depression [41]. This affects their active participation in rehabilitation and treatment adherence and results in poor quality of life and higher mortality [42]. Dementia is another common post-stroke complication with a similar prevalence of approximately 30% among stroke survivors and is also one of the leading causes of dependency [43]. Cognitive impairment may co-exist with depression, especially in elderly stroke survivors. One randomised trial showed that early recognition and successful treatment of the depressive disorder improved post-stroke impairment of cognitive function [44]. Awareness of early psychological and biological risk factors for depression and dementia after stroke will help to develop more tailored rehabilitation programmes, including psychological interventions. In both situations, awareness and a multidisciplinary approach are required, with neuropsychological testing tailored to the clinical situation. Effective partnerships with patients, their families, and carers help recognise early symptoms of depression and dementia, assist primary care doctors in timely treatments, and connect with broader post-stroke services for early interventions.

Finally, post-stroke care requires a well-organised comprehensive approach, including early and intensive rehabilitation, caregiver training, and early recognition of depression and dementia. Current medical practise is often focused on inpatient rehabilitation and better holistic transitional and community rehabilitation is needed following the transition from acute phase to long-term rehabilitation [45,46,47]. Furthermore, insufficient long-term community and outpatient rehabilitation resources contribute to unmet needs during long-term rehabilitation and care for post-stroke patients. Further improvements are required to establish a standardised rehabilitation delivery system and to develop projects to promote long-term rehabilitation. The provision of adequate therapy for post-stroke patients necessitates active board-certified physiatrist involvement; however, due to a lack of board-certified physiatrists. Additionally, many medical schools lack a department dedicated to teaching rehabilitation medicine. Establishing such a department would help students to learn about medical care and comprehensive post-stroke rehabilitation.

[C]omorbidities and lifestyle, patient values, and preferences

Patients with ischaemic stroke usually suffer from other major cardiovascular events due to the increased prevalence of multiple cardiovascular risk factors [48]. Management of these risk factors (including diabetes, smoking cessation, hyperlipidaemia, and especially hypertension) is vital in secondary stroke prevention. To optimise chronic disease management and minimise future major cardiovascular adverse events, a collaboration of physicians in a joint multidisciplinary team is essential. Since, in many countries, GPs are the first point of contact with the healthcare system, they can play an important role in care coordination (Fig. 2).

Collaboration of multidisciplinary team with general practitioners at the centre. A appropriate antithrombotic therapy, B Better functional and psychological status, C comorbidities and lifestyle, patient values, and preferences Servier Medical Art images were used for this figure (https://smart.servier.com)

Management of diabetes mellitus

Several studies have shown that stroke patients with diabetes have poorer functional and rehabilitation outcomes increased mortality, and longer hospital stays [49]. About 30% of patients with acute ischaemic stroke have prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, which is related to an increase in the risk of stroke recurrence [50, 51]. In such patients, good glycaemic control improves outcome, with a glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) target of < 53 mmol/mol (7%) recommended [52]. Pioglitazone has been shown to reduce the risk of future stroke [52], but its adverse events especially related to bone fractures, weight gain and heart failure, have restricted its use [53]. Newer agents, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, are helpful in patients with established cardiovascular disease reducing the risk of cardiovascular outcomes [54]. SGLT-2 inhibitors are especially beneficial in those with heart failure or chronic kidney disease. In addition to pharmacological treatment, exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and having a healthy diet can prevent the progression of prediabetes to type 2 diabetes [55].

Lipid modification

Lipid modification reduces cardiovascular events in stroke survivors. Current guidelines suggest intense statin therapy in patients after ischaemic stroke [8, 52]. In patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, strict treatment targets a reduction of more than 50% in low-density cholesterol (LDL-C) and LDL-C < 1.4 mmol/L (< 55mg/dl) [37]. However, the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) [43] and (Treat Stroke to Target) (TST) [56] trials point to an LDL-C target of < 70mg/dl in patients with non-cardioembolic stroke. Studies investigating the additive effect of ezetimibe or PCSK-9 inhibitors suggest that lower levels of LDL-C are safe and effective in reducing further cardiovascular outcomes [57, 58]. In most stroke patients, including those with AF (ESUS), intensive lipid-lowering should be pursued [59].

Management of hypertension

High blood pressure (BP) is the strongest risk factor for stroke development, and it is a recurrence, so even a small degree of decrease in BP can reduce the risk of stroke [60]. BP tends to be elevated in the hyperacute stage of stroke, though it may slowly subside to a lower level after a few days. However, increased BP persists in 25%–30% of stroke survivors at their discharge from the hospital [61].

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 8 studies, including 33,774 patients with ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attacks, showed that, during a median of 25 months follow-up, subsequent stroke occurred in 7.9% of patients under BP-lowering treatments vs 9.7% in patients taking placebo. However, mortality was similar in both groups (7.3% and 7.9%, respectively) [62]. It seems that BP-lowering treatments may reduce the risk of cardiovascular death but do not affect the all-cause mortality risk. Although guidelines suggest a BP target of < 130/80mmHg, the target BP and choice of antihypertensive drugs should be tailored to the stroke aetiology and patient characteristics [8, 52].

Lifestyle changes

Lifestyle changes, including a healthy diet and physical activity as basic components of the non-pharmacological approach, are essential to prevent recurrent strokes. In terms of healthy diets, recent guidelines recommend Mediterranean diets and low salt diets for stroke survivors. Some epidemiological diet studies showed that regular consumption of fish, and a high intake of fruits, vegetables, and fibre reduce the risk of stroke [63]. Similarly, low salt consumption and high potassium consumption are associated with lower stroke rates [64, 65]. On the contrary, high consumption of added fats and processed meats is associated with a 39% increase in stroke risk [66]. Choosing healthy meals can help reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.

When it comes to physical activity, because of the physical impairments, even simple tasks might be challenging for stroke survivors, and this results in being inclined to sit for lengthy periods. Therefore, it is vital to encourage stroke survivors to perform physical activities with support from physical and occupational therapists. Exercise training in stroke patients can improve hypertension, lipid profiles, glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, balance, gait speed, endurance, and disability [67]. Stroke survivors should engage in 40 min of moderate–vigorous-intensity aerobic activity three–four times per week when they can. Otherwise, physical activity should be tailored to their exercise tolerance, recovery stage, and other individual situations [8].

To summarise, in addition to a healthy diet and physical activity, smoking secession, low consumption of alcohol, and medication compliance are essential in patients with stroke. The vast majority of strokes can be prevented through BP control, a healthy diet, regular physical activity, and smoking cessation. Furthermore, Healthy lifestyle factors tend to cluster together so that those with regular physical exercise are likely to stop smoking, reduce alcohol and lose weight. Combinations of healthy lifestyle behaviours (such as regular exercise, and avoiding smoking and heavy drinking) have implications for reducing incidents of AF [68] and also, in case AF occurs, risks of AF-related complications [69, 70]. Also, targeting various risk factors has shown to have additive advantages for secondary stroke prevention; in particular, aspirin, statin and antihypertensive medications, combined with dietary modification and regular exercise, can result in an 80% cumulative risk reduction in recurrent vascular events [71]. All these lifestyle changes and management of comorbidities can be challenging for stroke survivors and their physicians. Although the benefits of a healthy lifestyle and vascular risk factor control are well documented, risk factors remain poorly controlled among stroke survivors. Thus, multidisciplinary support and coordination of subspecialties are needed instead of simple advice from their physician. At this point, GPs can manage the coordination of subspecialties to avoid polypharmacy and increase adherence, collaboration, and trust between patients and primary care doctors.

The primary care perspective

Most stroke management guidelines and recommendations focus on the acute in-hospital phase, diagnosis, and treatment of stroke, focusing on increasing survival rates. Therefore, the initial effects of a stroke in the acute stage are well known. However, for many stroke survivors and their families, acute stroke is just the beginning of a long journey of living disability caused by stroke. Primary care physicians are essential in optimising chronic disease control and managing and minimising complications. Many stroke survivors may develop various complications within months or years following a stroke, and the primary care physician is in an ideal position to manage the prevention of these complications. Also, they may help their stroke patients by recognising the potential complications that might occur after a stroke. In terms of rehabilitation, comparing two post-stroke rehabilitation programmes in Spain (home-based rehabilitation and standard outpatient rehabilitation in a hospital setting) revealed that both groups exhibited statistically significant gains in each assessment after physical therapy [72]. Using functional scales, these improvements were better in home-based rehabilitation patients than in-hospital patients [72].

The absence of an integrated care approach may result in pitfalls during follow-up and neglect of crucial components of overall health, such as cognitive/emotional impairment in stroke patients [73]. Several studies investigated the adherence of primary care settings to secondary stroke prevention guidelines. They revealed that many of these patients were not optimally treated according to guidelines, potentially due to the lack of a holistic, multidisciplinary and patient-orientated follow-up (Table 1) [74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. Accordingly, a secondary cardiovascular prevention study including patients with previous stroke followed-up in primary care demonstrated that only 53% of them were treated with statins, and 59% did not achieve the optimal BP, despite using antihypertensive treatment [81]. Although there are recently published guidelines and an increase in the awareness of patients with ischaemic stroke in primary care, still less than 50% of patients treated in primary care settings reach the prespecified treatment goals, including BP and lipid management [77].

The management of stroke survivors is a complex, lengthy, and interdisciplinary process. During this process, GPs may encounter some challenges. For example, Australian guidelines recommend developing comprehensive discharge care plans with stroke survivors and caregivers and sharing them with GPs [82]. Still, nearly a third of Australian stroke survivors are discharged home without receiving a discharge care plan [83]. Additionally, communication of each individual’s stroke-related risk factors (such as falls, recurrent stroke, infection, and depression) and their rehabilitation needs are rarely shared with GPs. Therefore, it is still a challenge to translate the efficacy of the interventions reported in clinical trials into routine clinical practice. To achieve this, cooperation between stroke specialists, internists, and GPs is essential. Since stroke specialists and internists play a crucial role in the acute phase of stroke, they are well versed in patients’ medical backgrounds, risk factors and rehabilitation requirements. Therefore, a discharge plan developed by stroke specialists or internists, which identifies specific individual risk factors, and their rehabilitation needs, help GPs during the long-term management of post-stroke patients. On the other hand, GPs play a key role in re-referring stroke survivors for evaluation when necessary and supporting their rehabilitation in the community thus, timely communication between stroke specialists (or internists) and GPs is essential (including the provision of agreed-upon goals, plans for a return to work or employment, and information about their rehabilitation).

Conclusion

Acute stroke is just the beginning of an extended challenge. After hospital discharge, many stroke survivors may develop a range of complications that necessitate the assistance of various specialities and coordination of subspecialties. However, they may feel abandoned due to a lack of an interdisciplinary and patient-centred approach. Family physicians can play an important role in the long-term care of stroke survivors by facilitating effective follow-up, information provision, and referral to specialist services when needed. Adequate, patient-centred, multidisciplinary support can help stroke survivors to help regain their independence or reduce dependence. For such work to succeed, close interdisciplinary collaboration between primary care physicians and other medical specialities is required. To bridge the gap between stroke specialists, family physicians and patients, an integrated care plan must provide a holistic and patient-oriented approach.

References

Feigin VL, Krishnamurthi RV, Parmar P, Norrving B, Mensah GA, Bennett DA et al (2015) Update on the global burden of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in 1990–2013: the gbd 2013 study. Neuroepidemiology 45:161–176

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C et al (2012) Disability-adjusted life years (dalys) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 380:2197–2223

Chohan SA, Venkatesh PK, How CH (2019) Long-term complications of stroke and secondary prevention: an overview for primary care physicians. Singap Med J 60:616–620

Lip GYH, Lane DA, Lenarczyk R, Boriani G, Doehner W, Benjamin LA et al (2022) Integrated care for optimizing the management of stroke and associated heart disease: a position paper of the European society of cardiology council on stroke. Eur Heart J 43:2442–2460

Lip GYH, Ntaios G (2022) “Novel clinical concepts in thrombosis”: integrated care for stroke management-easy as ABC. Thromb Haemost 122:316–319

Chao TF, Joung B, Takahashi Y, Lim TW, Choi EK, Chan YH et al (2022) 2021 focused update consensus guidelines of the Asia pacific heart rhythm society on stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Thromb Haemost 122:20–47

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C et al (2021) 2020 esc guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European society of cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European heart rhythm association (EHRA) of the esc. Eur Heart J 42:373–498

Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, Cockroft KM, Gutierrez J, Lombardi-Hill D et al (2021) 2021 guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 52:e364–e467

Fonseca AC, Merwick Á, Dennis M, Ferrari J, Ferro JM, Kelly P et al (2021) European stroke organisation (ESO) guidelines on management of transient ischaemic attack. Eur Stroke J. 6:Clxiii–clxxxvi

Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, Cotton D, Ounpuu S, Lawton WA et al (2008) Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med 359:1238–1251

Amarenco P, Denison H, Evans SR, Himmelmann A, James S, Knutsson M et al (2020) Ticagrelor added to aspirin in acute nonsevere ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack of atherosclerotic origin. Stroke 51:3504–3513

Shinohara Y, Katayama Y, Uchiyama S, Yamaguchi T, Handa S, Matsuoka K et al (2010) Cilostazol for prevention of secondary stroke (CSPS 2): an aspirin-controlled, double-blind, randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol 9:959–968

Toyoda K, Uchiyama S, Yamaguchi T, Easton JD, Kimura K, Hoshino H et al (2019) Dual antiplatelet therapy using cilostazol for secondary prevention in patients with high-risk ischaemic stroke in Japan: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 18:539–548

Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA (2012) Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med 367:817–825

Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, Barsan W, Conwit RA, Elm JJ et al (2018) Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk tia. N Engl J Med 379:215–225

Pan Y, Elm JJ, Li H, Easton JD, Wang Y, Farrant M et al (2019) Outcomes associated with clopidogrel-aspirin use in minor stroke or transient ischemic attack: a pooled analysis of clopidogrel in high-risk patients with acute non-disabling cerebrovascular events (chance) and platelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke (point) trials. JAMA Neurol 76:1466–1473

Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, Evans SR, Himmelmann A, James S et al (2020) Ticagrelor and aspirin or aspirin alone in acute ischemic stroke or tia. N Engl J Med 383:207–217

Wang Y, Meng X, Wang A, Xie X, Pan Y, Johnston SC et al (2021) Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in cyp2c19 loss-of-function carriers with stroke or tia. N Engl J Med 385:2520–2530

Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB, Easton JD, Granger CB, O’Donnell MJ et al (2014) Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol 13:429–438

Hart RG, Sharma M, Mundl H, Kasner SE, Bangdiwala SI, Berkowitz SD et al (2018) Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med 378:2191–2201

Diener H-C, Sacco RL, Easton JD, Granger CB, Bernstein RA, Uchiyama S et al (2019) Dabigatran for prevention of stroke after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med 380:1906–1917

Ntaios G, Papavasileiou V, Sagris D, Makaritsis K, Vemmos K, Steiner T et al (2018) Closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy in patients with cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 49:412–418

Sagris D, Harrison SL, Buckley BJR, Ntaios G, Lip GYH (2022) Long-term cardiac monitoring after embolic stroke of undetermined source: search longer, look harder. Am J Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.04.030

Kim JT, Park MS, Choi KH, Cho KH, Kim BJ, Han MK et al (2016) Different antiplatelet strategies in patients with new ischemic stroke while taking aspirin. Stroke 47:128–134

Sagris D, Georgiopoulos G, Pateras K, Perlepe K, Korompoki E, Milionis H et al (2021) Atrial high-rate episode duration thresholds and thromboembolic risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 10:e022487

Schnabel RB, Haeusler KG, Healey JS, Freedman B, Boriani G, Brachmann J et al (2019) Searching for atrial fibrillation poststroke. Circulation 140:1834–1850

Wallenhorst C, Martinez C, Freedman B (2022) Risk of ischemic stroke in asymptomatic atrial fibrillation incidentally detected in primary care compared with other clinical presentations. Thromb Haemost 122:277–285

Lip GYH, Keshishian A, Li X, Hamilton M, Masseria C, Gupta K et al (2018) Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. Stroke 49:2933–2944

Ntaios G, Papavasileiou V, Diener HC, Makaritsis K, Michel P (2012) Nonvitamin-k-antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke 43:3298–3304

Lee SR, Rhee TM, Kang DY, Choi EK, Oh S, Lip GYH (2019) Meta-analysis of oral anticoagulant monotherapy as an antithrombotic strategy in patients with stable coronary artery disease and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 124:879–885

Yasuda S, Kaikita K, Akao M, Ako J, Matoba T, Nakamura M et al (2019) Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 381:1103–1113

Lip GYH, Collet J-P, Haude M, Byrne R, Chung EH, Fauchier L et al (2018) 2018 joint european consensus document on the management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous cardiovascular interventions: a joint consensus document of the European heart rhythm association (EHRA), European society of cardiology working group on thrombosis, European association of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions (EAPCI), and European association of acute cardiac care (ACCA) endorsed by the heart rhythm society (HRS), Asia-Pacific heart rhythm society (APHRS), Latin America heart rhythm society (LAHRS), and cardiac arrhythmia society of Southern Africa (CASSA). EP Europace 21:192–193

Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, Granger CB, Kappetein AP, Mack MJ et al (2013) Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med 369:1206–1214

Guimarães HP, Lopes RD, de Barros e Silva PGM, Liporace IL, Sampaio RO, Tarasoutchi F et al (2020) Rivaroxaban in patients with atrial fibrillation and a bioprosthetic mitral valve. N Engl J Med 383:2117–2126

Chen LY, Leening MJ, Norby FL, Roetker NS, Hofman A, Franco OH et al (2016) Carotid intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness and the risk of atrial fibrillation: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study, multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (mesa), and the Rotterdam study. J Am Heart Assoc. 5:e002907

Bonati LH, Kakkos S, Berkefeld J, de Borst GJ, Bulbulia R, Halliday A et al (2021) European stroke organisation guideline on endarterectomy and stenting for carotid artery stenosis. Eur Stroke J 6:I–XLVII

Sagris D, Ntaios G, Georgiopoulos G, Kakaletsis N, Elisaf M, Katsiki N et al (2021) Recommendations for lipid modification in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a clinical guide by the Hellenic stroke organization and the Hellenic atherosclerosis society. Int J Stroke 16:738–750

Hall P, Williams D, Hickey A, Brewer L, Mellon L, Dolan E et al (2016) Access to rehabilitation at six months post stroke: a profile from the action on secondary prevention interventions and rehabilitation in stroke (Aspire-s) study. Cerebrovasc Dis 42:247–254

Quinn TJ, Richard E, Teuschl Y, Gattringer T, Hafdi M, O’Brien JT et al (2021) European stroke organisation and European academy of neurology joint guidelines on post-stroke cognitive impairment. Eur Stroke J. 6:I–xxxviii

Kalra L, Evans A, Perez I, Melbourn A, Patel A, Knapp M et al (2004) Training carers of stroke patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 328:1099

Hackett ML, Pickles K (2014) Part i: Frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke 9:1017–1025

Towfighi A, Ovbiagele B, Husseini NE, Hackett ML, Jorge RE, Kissela BM et al (2017) Poststroke depression: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 48:e30–e43

Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A 3rd, Goldstein LB, Hennerici M, Rudolph AE et al (2006) High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 355:549–559

Kimura M, Robinson RG, Kosier JT (2000) Treatment of cognitive impairment after poststroke depression. Stroke 31:1482–1486

Kinoshita S, Abo M, Okamoto T, Miyamura K (2021) Transitional and long-term care system in Japan and current challenges for stroke patient rehabilitation. Front Neurol 12:711470

Leigh JH, Kim WS, Sohn DG, Chang WK, Paik NJ (2022) Transitional and long-term rehabilitation care system after stroke in Korea. Front Neurol 13:786648

Hempler I, Woitha K, Thielhorn U, Farin E (2018) Post-stroke care after medical rehabilitation in Germany: a systematic literature review of the current provision of stroke patients. BMC Health Serv Res 18:468

Zhang Y, Wang C, Liu D, Zhou Z, Gu S, Zuo H (2021) Association of total pre-existing comorbidities with stroke risk: a large-scale community-based cohort study from China. BMC Public Health 21:1910

Lei C, Wu B, Liu M, Chen Y (2015) Association between hemoglobin a1c levels and clinical outcome in ischemic stroke patients with or without diabetes. J Clin Neurosci 22:498–503

Pan Y, Chen W, Wang Y (2019) Prediabetes and outcome of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 28:683–692

Callahan A, Amarenco P, Goldstein LB, Sillesen H, Messig M, Samsa GP et al (2011) Risk of stroke and cardiovascular events after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in patients with type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome: secondary analysis of the stroke prevention by aggressive reduction in cholesterol levels (Sparcl) trial. Arch Neurol 68:1245–1251

Dawson J, Béjot Y, Christensen LM, De Marchis GM, Dichgans M, Hagberg G et al (2022) European stroke organisation (ESO) guideline on pharmacological interventions for long-term secondary prevention after ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Eur Stroke J. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969873221100032

Kanis J, Oden A, Johnell O (2001) Acute and long-term increase in fracture risk after hospitalization for stroke. Stroke 32:702–706

Brown E, Heerspink HJL, Cuthbertson DJ, Wilding JPH (2021) Sglt2 inhibitors and glp-1 receptor agonists: established and emerging indications. Lancet 398:262–276

Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P et al (2001) Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 344:1343–1350

Amarenco P, Kim JS, Labreuche J, Charles H, Abtan J, Béjot Y et al (2020) A comparison of two LDL cholesterol targets after ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 382:9

Giugliano RP, Pedersen TR, Saver JL, Sever PS, Keech AC, Bohula EA et al (2020) Stroke prevention with the pcsk9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9) inhibitor evolocumab added to statin in high-risk patients with stable atherosclerosis. Stroke. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027759

Bohula EA, Wiviott SD, Giugliano RP, Blazing MA, Park JG, Murphy SA et al (2017) Prevention of stroke with the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome in improve-it (improved reduction of outcomes: vytorin efficacy international trial). Circulation 136:2440–2450

Choi KH, Seo WK, Park MS, Kim JT, Chung JW, Bang OY et al (2019) Effect of statin therapy on outcomes of patients with acute ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 8:e013941

Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL, Rodgers A (2004) Blood pressure and stroke: an overview of published reviews. Stroke 35:1024

Grassi G, Arenare F, Trevano FQ, Dell’Oro R, Mancia AG (2007) Primary and secondary prevention of stroke by antihypertensive treatment in clinical trials. Curr Hypertens Rep 9:299–304

Boncoraglio GB, Del Giovane C, Tramacere I (2021) Antihypertensive drugs for secondary prevention after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 52:1974–1982

Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, Fadnes LT, Keum N, Norat T et al (2017) Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol 46:1029–1056

Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP (2009) Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 339:b4567

Vinceti M, Filippini T, Crippa A, de Sesmaisons A, Wise LA, Orsini N (2016) Meta-analysis of potassium intake and the risk of stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 5:e004210

Judd SE, Gutiérrez OM, Newby PK, Howard G, Howard VJ, Locher JL et al (2013) Dietary patterns are associated with incident stroke and contribute to excess risk of stroke in black Americans. Stroke 44:3305–3311

Ivey FM, Hafer-Macko CE, Macko RF (2008) Exercise training for cardiometabolic adaptation after stroke. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 28:2–11

Lee SR, Choi EK, Ahn HJ, Han KD, Oh S, Lip GYH (2020) Association between clustering of unhealthy lifestyle factors and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep 10:19224

Lee SR, Choi EK, Park SH, Lee SW, Han KD, Oh S et al (2022) Clustering of unhealthy lifestyle and the risk of adverse events in patients with atrial fibrillation. Front Cardiovasc Med 9:885016

Ozdemir H, Sagris D, Lip GYH, Abdul-Rahim AH (2023) Stroke in atrial fibrillation and other atrial dysrhythmias. Curr Cardiol Rep 25:357–369

Hackam DG, Spence JD (2007) Combining multiple approaches for the secondary prevention of vascular events after stroke: a quantitative modeling study. Stroke 38:1881–1885

López-Liria R, Vega-Ramírez FA, Rocamora-Pérez P, Aguilar-Parra JM, Padilla-Góngora D (2016) Comparison of two post-stroke rehabilitation programs: a follow-up study among primary versus specialized health care. PLoS ONE 11:e0166242

Santos E, Broussy S, Lesaine E, Saillour F, Rouanet F, Dehail P et al (2019) Post-stroke follow-up: time to organize. Rev Neurol (Paris) 175:59–64

Doogue R, McCann D, Fitzgerald N, Murphy AW, Glynn LG, Hayes P (2020) Blood pressure control in patients with a previous stroke/transient ischaemic attack in primary care in Ireland: a cross sectional study. BMC Fam Pract 21:139

Han J, Choi YK, Leung WK, Hui MT, Leung MKW (2021) Long term clinical outcomes of patients with ischemic stroke in primary care: a 9-year retrospective study. BMC Fam Pract 22:164

Pedersen RA, Petursson H, Hetlevik I (2019) Stroke follow-up in primary care: a Norwegian modelling study on the implications of multimorbidity for guideline adherence. BMC Fam Pract 20:138

Pedersen RA, Petursson H, Hetlevik I (2018) Stroke follow-up in primary care: a prospective cohort study on guideline adherence. BMC Fam Pract 19:179

Abdul Aziz AF, Ali MF, Yusof MF, Che’ Man Z, Sulong S, Aljunid SM (2018) Profile and outcome of post stroke patients managed at selected public primary care health centres in peninsular Malaysia: a retrospective observational study. Sci Rep 8:17965

de Weerd L, Rutgers AW, Groenier KH, van der Meer K (2012) Health care in patients 1 year post-stroke in general practice: research on the utilisation of the Dutch transmural protocol transient ischaemic attack/cerebrovascular accident. Aust J Prim Health 18:42–49

Bansal V, Lee ES, Smith H (2021) A retrospective cohort study examining secondary prevention post stroke in primary care in an Asian setting. BMC Fam Pract 22:57

Heeley EL, Peiris DP, Patel AA, Cass A, Weekes A, Morgan C et al (2010) Cardiovascular risk perception and evidence-practice gaps in Australian general practice (the Ausheart study). Med J Aust 192:254–259

Wright L, Hill KM, Bernhardt J, Lindley R, Ada L, Bajorek BV et al (2012) Stroke management: Updated recommendations for treatment along the care continuum. Intern Med J 42:562–569

Sheehan J, Lannin NA, Laver K, Reeder S, Bhopti A (2022) Primary care practitioners’ perspectives of discharge communication and continuity of care for stroke survivors in Australia: a qualitative descriptive study. Health Soc Care Community 30:e2530–e2539

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None for all authors in relation to this manuscript.

Human and animal rights statement and Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required. Preparation of this literature review manuscript did not involve any research participants.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ozdemir, H., Sagris, D., Abdul-Rahim, A.H. et al. Management of ischaemic stroke survivors in primary care setting: the road to holistic care. Intern Emerg Med 19, 609–618 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-023-03445-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-023-03445-y