Abstract

There have been important studies of recent income inequality and of poverty in South Africa, but very little is known about the long-run trends over time. There is speculation about the extent of inequality when the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, but no hard evidence. In this paper, we provide evidence that is partial—being confined to top incomes—but which for the first time shows how the income distribution changed on a (near) annual basis from 1913 onwards. We present estimates of the shares in total income of groups such as the top 1% and the top 0.1%, covering the period from colonial times to the twenty-first century. For a number of years during the apartheid period, we have data classified by race. The estimates for recent years bear out the picture of South Africa as a highly unequal country, but allow this to be placed in historical and international context. The time series presented here will, we hope, provide the basis for detailed investigation of the impact of South African institutions and policies, past and present. But the similarity of the changes over time in top incomes across the four ex-dominions suggests that national developments have to be seen in the light of common global forces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Income inequality in South Africa has received much attention. Over the last years, there have been important studies of recent inequality and poverty, and a heated debate about trends in post-apartheid transition.Footnote 1 South Africa has long been regarded as having one of the most unequal societies in the world. Consistent with this view, the country has the highest survey-based Gini coefficient of household consumption per capita in Povcal database (63.4 in 2011; 63 in 2014). In this paper, we approach the subject from a different direction: the extent and evolution of top incomes. We present estimates of the shares in total income of groups such as the top 1% and the top 0.1%, covering, with gaps, more than a hundred years. As in other countries, top incomes are difficult to measure with precision. They are often not well covered by the household surveys that are today the primary source of evidence about the distribution of income. A partial picture can, however, be obtained from the information contained in the income tax returns, and these are the sources employed in this paper.

In this field, and in the related area of national income totals, South African researchers were among the pioneers. Leslie (1935, 1936, 1937) used income tax data to examine the effect on the South African distribution of income of the abandonment of the Gold Standard by Britain in 1931. Frankel and Herzfeld (1943) published estimates of the income distribution among “Europeans” in South Africa based on the income tax returns, by making use of control totals from the census of population and from the national accounts; their use of external information to complement income tax data pre-dated by ten years the study of upper income groups in the US by Kuznets (1953). Graaff (1946) assembled a series based on South African Super Tax data covering the years 1915 to 1942 to examine the stability of the distribution and the causes of fluctuations in income concentration. In seeking to exploit the (more than a) century of income tax data now available, we are therefore following in a long-established research tradition.

The picture obtained from tax data is only a partial one because not everyone has to provide income information to the tax authorities, and in earlier years, the tax-paying population was a small minority of the total population; they were the better-off and, in the case of South Africa, very largely white. The picture is also partial in that the income recorded, gross income assessed for tax purposes, does not necessarily capture the full extent of the economic advantage accruing to those at the top of the distribution, and certain categories of income, notably dividends, are incompletely covered. Conclusions drawn from the income tax data are therefore surrounded by qualifications.

The tax data do however provide insight into the degree of inequality at the top. Combined with external information about the total population and the total income, as in the pioneering work of Frankel and Herzfeld (1943) but covering all races, the tax returns allow estimates to be made of the share of the top 1%. To the extent that the tax definition of income falls short of that ideally applied, these estimates are likely to be an under-statement.

Taken together, the historical series covers, with some gaps, more than a hundred years. This was an eventful period. It goes from the colonial days, through the Dominion phase, the Natives Land Act of 1913, the effective independence in 1931, the systematisation of segregation in the form of apartheid following the National Party government elected in 1948, the Group Areas Acts in the 1950s, the declaration of a republic in 1961, international sanctions and trade boycotts, to the establishment of multi-racial democracy and the election of the ANC government in 1994.Footnote 2 How far do the top income shares reflect these major political events? Or was inequality at the top dominated by underlying economic forces, such as the movements in gold sales? How far were changes in the South African top income shares different from those in other countries? In the paper, we make comparisons with the findings for Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and with other former colonial territories in Africa.

Throughout this history, there was much concern about the high levels of poverty in South Africa, and it is on the bottom of the income distribution that attention has rightly focussed. At the same time, poverty has to be seen in the context of the distribution as a whole. As noted by Leibbrandt et al., “in addition to high poverty levels, South Africa’s inequality levels are among the highest in the world” (2010, page 9). Our estimates of top incomes allow us to examine whether that has always been the case. The conclusion of Graaff (1946) was that the degree of income concentration (derived from the Pareto coefficient) was “fairly stable” over the long period. But now, we have many more years of data. Did this stability, however, remain in the apartheid years? Or was there a long-run trend in top income shares? In a recent article on inequality, van der Berg asked “what was the case in South Africa over the past century?” and went on to say that “no data exist to give a definitive answer” (2011, page 125). Our estimates are not definitive, but they provide a point of departure for those seeking to understand the long-run pattern of income inequality in South Africa.

Many readers will want to go first to the results. However, an appreciation of the methods used to arrive at the estimated top income shares is necessary to give due weight to their limitations. We therefore begin in Sect. 2 with a description of the income tax data: one of the contributions of this paper is the reconstruction of all the distributional data published by official sources on the basis of the income tax in South Africa since 1903. As already explained, the tax data cannot be employed on their own. The published distributions of taxpayers by income ranges have to be accompanied by external control totals for the total adult population and for total household income, and these are described in Sect. 3. The results for top income shares in South Africa from 1903 to 2007 are set out in Sect. 4, where we consider the changing shape of the upper tail. The findings for South Africa are set in international context in Sect. 5, where we make comparisons with the findings for Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and with other former colonies of the British Empire. In seeking to understand to understand the evolution of top income shares, we preliminary explore three determinants: conquest, discrimination and development. The main conclusions are summarised at the end.

2 Where do the estimates come from?

The basic sources used in this paper are the tables published by the income tax authorities for the Cape Colony (data for 1903–1907) and the Union of South Africa (data from 1913). The Union was formed as a British Dominion in May 1910 from the former colonies of Cape of Good Hope, Natal, Orange River Colony (or Free State) and Transvaal. Income tax was introduced into the Cape Colony with effect for incomes for the year starting on 1 July 1903, and information on the tax was published in the Report of the Commissioner of Taxes for the year 1904–1905, and in subsequent reports. The tax was levied in the new Dominion with effect for incomes for the year starting on 1 July 1913. In what follows, we denote the “income year” (IY) by the calendar year in which the income period began, in this case 1913. Information on the distribution of taxpayers by ranges of income was published on a regular basis in the Annual Report of the Commissioner for Inland Revenue (less detailed data were published initially also in the Official Year Book of the Union).

The taxation of individual income under the Union from 1913 involved a Normal tax, covering (in 1915) persons with income in excess of £300 a year, and a Super Tax, in force until 1958, levied on higher income persons, covering (in 1915) persons with incomes in excess of £2500 a year. The statistics for the former cover a larger proportion of the population (some 58,000 taxpayers in 1916, compared with fewer than 2000 Super Tax payers), but the Normal tax statistics exclude dividend income, a point discussed further below. In later years, information was published in South African Statistics, which appeared biennially from 1968. In 2009, the National Treasury and the South African Revenue Service began a new publication entitled 2008 Tax Statistics, containing information for 2002 to 2005, and which has appeared regularly since then (National Treasury and South African Revenue Service 2009).

The data employed here are not in the form of individual tax records, which no longer exist for most of the period studied; rather, we make use of published tabulations. The information necessary for the estimation of top income shares is the distribution of taxpayers assessed by ranges of income and, ideally (present in many, but not all, years) the amount of income in each range. Interpolation is involved (see Atkinson 2007), but the tabulations are in many cases extremely detailed: for example, in the data for 1917, there are 29 ranges, 10 of which contain fewer than 100 observations (one containing only 5 taxpayers). We have been able to locate income tax data for most years. The data sources are listed by income year in Appendix Table 1.Footnote 3

The data are the product of an administrative process, and this process can affect the resulting estimates. Two important features should be discussed here. The first is the definition of taxable income. As in any income tax system, certain types and amounts of income were exempted. In 1951, for example, these exemptions included (in addition to the emoluments of the Governor-General) interest up to £25 from the Post Office Savings Bank, war pensions and miners’ phthisis awards, and—of particular significance for top incomes—dividend income. Under the Normal Tax/Super Tax regime, dividend income was not assessed under the Normal Tax but under the Super Tax. A separate Dividend tax was levied (with higher rates for companies engaged in gold and diamond mining). The Super Tax data are therefore more complete, and for this reason have been used in earlier studies such as Graaff (1946). However, they cover a smaller fraction of the upper incomes. The estimates prior to the 1940s are limited to the share of the top 0.05%, whereas using the Normal Tax data we are able to estimate the share of the top 1%.Footnote 4 In view of this, we give two series: series excluding dividends (Appendix Table 5) based on Normal Tax data, up to 1953, and series including dividends (Appendix Table 6) based on the Super Tax data. Following the abolition of Super Tax in 1959, the latter is continued using the Personal Income Tax data, which included dividend income to varying degrees. Initially, some 2/3 of dividends accruing to top taxpayers were taxed. There is however an important gap for the years 1994 to 2001.Footnote 5 This limits our capacity to record distributional changes during this crucial period. It also means that we find it hard to judge the comparability of the earlier estimates with those from 2002 onwards (third series given separately in Appendix Table 7), these being additionally affected by changes in the tax code (mainly the partial inclusion of capital gains in taxable income, offset by the omission of a fraction of dividend income) and by the significant improvement of tax collection capabilities.

Estimates of the distribution of top incomes are obtained by interpolation from the published tabulations. Where there is information on both the number of persons and the total income in the range, we use the mean-split histogram. Interpolation necessarily introduces an additional source of error; however, the tabulations used are in many cases extremely detailed: for example, in the data for IY1917 there are 29 ranges, 10 of which one contain fewer than 100 observations (one containing only 5 taxpayers). For the years (1953 and 1963 to 1993) when there is only information on numbers, we have fitted a Pareto distribution to the cumulative frequencies for each interval (i.e. separate coefficients for each interval) and used this to estimate the income shares. In view of the increased error introduced, we have shown (in Fig. 2) a (gross) confidence interval constructed by assuming that the mean for the interval was equal to either the lower or upper end points.Footnote 6

The second feature concerns the timing of assessments. The data for the early part of the period refer to incomes whose assessment has been completed within the fiscal year following the income year (see Appendix Table 1). In some, typically the higher income and more complicated cases, assessment may take longer to be completed, and for quite a number of later years there are data based on a 24-month period of assessment. Earlier studies have drawn attention to this issue, but have tended to regard the 12-month assessment period as adequate: “it is unlikely that the (fairly complete) sample given is biased in favour of the exclusion of incomes of any particular size” (Graaff 1946, p. 28). The impact on the estimated shares of different assessment periods depends on the proportion covered within the 12 months, and on the nature of those incomes requiring longer assessment. In Appendix Table 8, we have shown the proportion of assessments (and of tax assessed) within 12 months, compared with the final totals reported as of 1955. The evidence for the income years prior to 1940 is re-assuring, since typically around 90% of assessments had been completed, and the average tax per assessment did not differ greatly. However, from 1940, during the war, the proportion assessed fell and the proportion of tax assessed fell to a greater extent. The latter suggests that the taxpayers assessed later were not a random drawing: as shown in Appendix Table 9, the difference in the top 1% share could be as much as 8% points, which would give a quite different picture. In view of these findings, we have decided not to use the tax data for the years after 1939 for which we have only + 12 month figures (the results for these years (1940–1943 and 1950) are shown for reference in Appendix Table 10). For the other years, estimates are based on the longest assessment period available. For the period from 1955 to 1961, the information is mostly available only for a 12-month assessment period, and we have assumed that, in these post-war conditions, these estimates are more complete.

3 How can the tax figures be set in context?

In isolation, the tax statistics cannot tell us a great deal about income inequality. The figures have to be related to the total population and to total income. Neither of these totals is easy to estimate and the South African case is particularly difficult.

3.1 Control total for population: a challenge

The income tax in South Africa, as in most countries, was originally levied on the tax unit, treating a married couple as one unit, but since 1990 has been based on the individual. We need therefore control totals for tax units from 1913 to 1989 and for total individuals from 1990. The derivation of these totals involves the following steps: (1) making an estimate of total population, (2) excluding those aged under 15, to arrive at an assumed total of “individuals” for tax purposes, and (3) before 1990, subtracting the number of married women to arrive at a total for “tax units”. The selection of the age of 15 to define tax units is arbitrary but does not seem unreasonable and is in line with previous work (see Atkinson and Piketty 2007, 2010).

We focus here on step (1), the estimation of the total population of South Africa, which is surrounded by a number of difficulties (steps (2) and (3) are described in the “Appendix”). The chapter on population in the 1949 Handbook on race relations in South Africa (Hellmann 1949) opens with the statement that “the statistical facts concerning the bulk of our population are … utterly inadequate. …Our Office of Census and Statistics has done excellent work, but it lacks the essential statistical raw material” (Sonnabend 1949, p. 4). The first simultaneous count in the four territories later incorporated into the Union was carried out in 1904, but only four censuses of population in the next 45 years covered non-Europeans (1911, 1921, 1936 and 1946), and there was only incomplete registration of births and deaths. There were over that period also censuses in 1918, 1926 and 1931, but these covered only the European population. Moreover, there were grounds for supposing that the censuses in the early years significantly under-stated the size of the non-European population. “Each successive census enumeration of Africans, and to a lesser degree, of Coloured, has become more accurate and complete. The fact that the census of 1936 revealed the presence of 6,596,689 Natives against 4,697,813 in 1921 must be partly due to the inclusion in 1936 of a considerable number left out in the previous census. This likewise holds good, though to a lesser degree, of the census for 1946” (Sonnabend 1949, p. 10). Working in the opposite direction was the fact that the 1946 census was based on the de facto population: i.e. those actually present. As a result, “a large number of immigrants and temporary labourers from neighbouring territories are included in the Union totals” (Sonnabend 1949, p. 5).

The weaknesses of the South African population census may well have intensified during the apartheid period. Orkin, Lehohla and Kahimbaara say of the 1998 census that “it was a pastiche of small-area detail, of variable quality, from the four ‘states’ and ‘white’ South Africa. … The counts from [the ‘white’] areas were generally accepted as reasonably accurate. But in many urban ‘townships’, informal settlements and peasant-farmed rural areas, where the residents were overwhelmingly African, mapping was not uniformly available or else various areas were deemed inaccessible due to political unrest. In some cases household interviews were conducted but without prior demarcation. … In others, dwellings were counted on aerial photographs, and populations then imputed using household densities obtained from sample surveys” (1998, p. 268). It is therefore scarcely surprising that the adjusted data from the 1991 census give a total of 31.0 million compared with an enumerated total of 26.3 million (South African Statistics 2009, Table 2.3), a difference of 18%.

In intermediate years, a further difficulty has been the fact that the published figures for years before 1991 are affected by the exclusion of the population of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei (referred to as “the TBVC states”). This has the consequence that the table for total population in South African Statistics 2009 (Table 2.3) has figures for 1904, 1911, 1921, 1936, 1946, 1951, 1960 and 1970 covering the whole of South Africa (except for Walvis Bay), but the data for 1980 and 1985 exclude the TBVC states. Figures are given for 1991 on the same basis and with the 1994 boundaries. The differences are large: it is estimated that the population of the former TBVC states at the 1991 census was 6.751 million.

In view of the difficulties caused by these two types of “missing” population (the under-enumerated and the TBVC states), we have worked back from the current mid-year population estimates (published by Statistics South Africa in the annual publication P0302), but have used the UN Population Division estimates to cover the period before 1991 (the sources are given in Appendix Table 2). This takes the series back to 1950. At that date, the series is some 7% higher than the mid-year estimates published in the Official Yearbook of the Union (OYB) for 1954–55, p. 680. There is the further hiatus in the 1930s noted above. The OYB number 18 for 1938 reported (page 1035) that the population estimates had been revised in the light of the 1936 census, and the upward revision was substantial: the estimate for the total population in 1935, for example, was 9.4 million, compared with 8.6 million in the previous edition of the OYB (page 1047), an increase of 10%. For 1949 and earlier years, we have therefore used the estimates given in Feinstein (2005, p. 258), which adjust for under-enumeration progressively from 1922.

The resulting series for total tax units and total adults are given in Appendix Table 3; the series for the Cape Colony are given in Appendix Table 4.

3.2 Control total for total income

The tax records only cover a part of total household income. One of the major contributions of Kuznets’ study Shares of upper income groups in incomes and savings (1953) was to combine income tax data with national accounts estimates of total income. However, he was not the first, having been preceded by South African economists Frankel and Herzfeld, who made estimates of the “European” income distribution in South Africa in 1943. Drawing attention to the limited coverage of the tax return data on their own, these authors argued that “by combining the national income and income tax statistics … it is possible to obtain a more general picture” (1943, pp. 121–2).

The national income estimates provide our starting point here. Our aim is to compare the incomes recorded in the tax returns with the total of household income after transfers but before tax as recorded in the national accounts. This means that the comparison total is larger than the total of income that would be subject to tax if the personal tax allowances were removed; the control total includes for example Post Office Savings Bank interest that is not taxable if below a specified amount. To this extent, we are understating the top income shares since this non-taxable income is omitted from the numerator. The household income totals are however less than total national income. As is explained by Frankel and Herzfeld (1943, p. 128), household income is obtained by subtracting “income which is not distributed to individuals”, that is undistributed company profits and the profits of official bodies, and by adding back the interest paid by government and official bodies and transfer payments such as unemployment relief. Their total (not including transfer payments) for 1939/40 came to 94% of national income. For 1953, the first overlapping year between the household income series of the Bureau of Census and Statistics and the net national income series of Frankel, the ratio is also 94%.

In the South African context, it should be noted that the control total does not include incomes paid to foreign factors of production. There is an important distinction between national income and domestic income (see Franzsen 1954, and Samuels 1963a, b). Geographical income “is reduced to a national basis by adding the income accruing to factors owned by its own citizens, but employed outside its frontiers, and deducting the income accruing to factors owned by foreigners, but employed within its frontiers” (Bureau of Census and Statistics 1954, page 356). The most important deductions by the Bureau of Census and Statistics are for the wages of foreign workers employed in South African mines, profit income accruing to the owners of foreign capital invested in the Union, and interest paid abroad. This leads the estimated total national income in 1951–52 to be some 90% of total geographical income (although Franzsen 1954, Table 1, suggests that the deduction for foreign capital is overstated). Multiplying 90% by the earlier 94% suggests that the household income series is some 85% of geographical (domestic) product.

The control totals used here (see “Appendix, Section A.4”) are derived by working backwards from the recent published national accounts series to the older period. For 1953–2010, the National Accounts of South Africa give total Households’ Disposable Income plus the Taxes on Income and Wealth paid by households: i.e. total household gross income. For the years before 1953, a series for household disposable income does not exist. Consequently, we have linked the previous series backwards following net national income, assuming that household income moved in line. The need to make this assumption introduces a further element of uncertainty surrounding the control totals, although, given the long history of research on national income in South Africa, there are good reasons for believing that the South African totals are more reliable than those used in many other countries. Of the total thus obtained, we have taken 80% for the years before 1993 in order to exclude elements present in the national accounts that are not comparable to the income definition provided in the tax information, and to reduce the potential overestimation of the income total induced by the backward linking.

The resulting series for total reference income is given in Appendix Table 3.

3.3 Summary

We have devoted some space to the processes by which we arrived at the estimates examined in the next sections of the paper. It is not straightforward to go from the published income tax tabulations to estimates of top income shares. It is necessary to examine the structure of the tax system and how it has been administered. The income tax data can only the interpreted in the light of external information and the assembly of this information for a period of some hundred years requires a considerable investment. An understanding of these processes is necessary to appreciate the limitations of the estimates, but may also provide confidence in their use.

4 Top income shares in South Africa

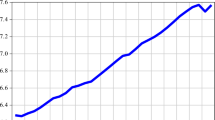

Our estimates for top income shares span a period that saw substantial growth in average real income per head, but at far from a uniform rate. As may be seen from Fig. 1, average real income per adult rose from 1913 to 1928, fell in the Great Depression, and then grew rapidly up to the beginning of the 1970s. Growth was un-interrupted by the First and Second World Wars. In 1913, South Africa had a much lower per capita GDP than Australia, Canada and New Zealand (Feinstein 2005, p. 6), but it grew faster from 1913 to 1950 than these other Dominions. By 1971, real income per head was some four times its 1913 value. Real income per adult then, however, began to decline, so that by 1994, it was some fifth lower than a quarter of a century before. Only in the twenty-first century has growth in real income per adult been resumed.

Average real income and price index in South Africa, 1914–2014. Source: Table 3. Notes: Figure reports the average real income per adult (aged 15 and above), expressed in 2014 Rand. The Price Index is equal to 100 in 2014. Memo: In 2014, 1 US Dollar = 0.1 Rand

What was happening to top incomes over this period? Fig. 2 shows the shares of the top 1%, top 0.5% and top 0.1%. The results relate to tax units (up to 1990) and to assessed (gross) income before tax. At the beginning of the period, the top 1% numbered 26,500 tax units. At that time, the number of white tax units was some 600,000, so that, if the top 1% had all been white, they would have been some 4.5% of the white total. The series marked with solid symbols is series A, derived from the Normal Tax data excluding dividends. As may be seen, where the series may be compared there is a noticeable difference, but the movements over time are similar. For the years 1944 to 1949 where there is overlap, the series B estimates are higher by 7.5% (top 1%), 9% (top 0.5%) and 15% (top 0.1%). In what follows, where combining series A and B, we increase the series A estimates by these percentages.

Top income shares in South Africa 1913–2007. Notes: The confidence interval is depicted for those years for which only frequencies (number of tax assessments), have been used (as incomes per range are not available). The lower limit of the interval assumes that the average income in each range of the published tabulations is equal to the range lower limit. The upper limit of the interval assumes that the average income in each range is equal to the range upper limit; the average income in the top open bracket assumes an inverted Pareto-Lorenz coefficient equal to 2.5 for 1963–1989 and equal to 1.5 for 1990–1993. Source: Appendix Tables 5, 6 and 7

In 1913, the share of the top 1% was over 25%, meaning that this group had on average more than 25 times their proportionate share. For the top 0.5%, the share was around 18%, and for the top 0.1% around 8%, implying that these groups had, respectively, 36 and 80 times their proportionate shares. This is a high level of concentration, but not without parallel before the First World War: the top 1% share in the Netherlands in 1914 was over 20%.

It is evident from Fig. 2, however, that the position of top income groups has been far from stable over time. The instability is in part short-run. Both the First and Second World Wars saw an upward spike in the top shares. But, leaving these episodes aside, the overall impression is that of a continuing downward trend from 1913 to the 1980s. The share of the top 1% was halved. Our conclusions about the long-run development differ therefore from those of Graaff, who found that: “the concentration (and so the distribution) of incomes … is stable in the long period” (1946, p. 46). He was, of course, only able to use data for the first part of the century, but our conclusions also differ in that we are using control totals to estimate the shares in total income. We should also note that the downward trend is not constant: the speed of fall in top income shares was faster in the 1930s and in the 1950s.

The long-run fall over much of the twentieth century shown in Fig. 2 is similar to the pattern in other countries (discussed further in the next sections). In the majority (but not all) of those countries, there was a reversal of this trend in the final part of the century. Figure 2 suggests that the same is true in South Africa. As noted earlier, the hiatus in the production of the necessary statistics means that we should be cautious in joining the points for 1993 and 2002. It is possible that the increase reflects greater effectiveness in collecting tax, and the partial inclusion of capital gains, so that the true increase is overstated; on the other hand, the omission of dividend income works in the opposite direction. There was also the move from a tax unit to an individual basis for taxation. Taking the post-2002 figures on their own, we can see that top income shares have increased, but we must stress again that the comparability of data (and, by extension, of the level of shares) in the 21th century with the years before 1993 is not granted.Footnote 7 Yet, the recent figures bear out the picture of South Africa as a highly unequal country.

4.1 The changing shape of the upper tail of the distribution

The rate of change in top shares differs across the different income groups. Whereas the share of the top 0.5% went from around 18% in 1914 to around 8% in 1993 (a fall of some 55%), the share of the next 0.5% (the top 1–0.5%) fell from 7% cent to around 5%, which is a proportionately smaller decline. This suggests that the shape of the upper part of the distribution has been changing; it is not simply a question of all incomes being scaled back proportionately.

The changing shape may be examined by looking at the “shares within shares”: the share, for example, of the top 0.5% in the total income of the top 1%. In 1914, this share was around three-quarters (18% out of 25%). By 1939, the proportion had fallen a little to around 70%, and by the end of the 1980s it was down to around 60%. The within-group distribution became less concentrated. The shares-within-shares calculation has the advantage of not relying on the control totals for income, and thus avoiding the uncertainties surrounding these totals noted in Sect. 3. It is also directly related to the Pareto coefficient. The Pareto law is usually considered as a good approximation of the top segment—say, the top 10 or top 1%—of the observed income distribution. In its simplest form, the Pareto law applies with a constant coefficient to the top µ% of the distribution and it is given by the following equation:

where 1 − F(y) is the distribution function (i.e. the fraction of the population with income above y), yµ is the income threshold that one needs to pass in order to belong to the top µ% and α is the Pareto coefficient. The characteristic property of the Pareto law is that the ratio β(y) between the average income above y and y does not depend on the income threshold y. That is:

Intuitively, β = α/(α − 1), which can viewed as the inverted Pareto-Lorenz coefficient, measures the fatness of the upper tail of the income distribution. For instance, a coefficient β = 2 means that the average income above 100,000 Rand is equal to 200,000 Rand, the average income above 1 million Rand is equal to 2 millions Rand, and so on. In case β = 3, the average income above 100,000 Rand is equal to 300,000 Rand, the average income above 1 million Rand is equal to 3 millions Rand. Higher β typically corresponds to a society with higher top income shares and higher inequality.

There are two important caveats to have in mind, however. First, although the general Pareto shape does provide a relatively good fit for the top parts of observed distributions in pretty much every country and time period for which we have data, it is important to note that the Pareto coefficients do vary widely over time and across countries. Next, it is also important to note that, for a given country and year, α and β are not exactly constant, even in the upper part of the distribution. For any given distribution function 1 − F(y), one can always define the “empirical” α and β. If the share of the top 0.5% is denoted by S0.5 and the share of the top 1% is denoted by S1, then, if the upper tail of the distribution follows a Pareto distribution, then the coefficient, α can be estimated from the income shares, using the formula that 1 − 1/α = log10{S1/S0.5}/log10{2}. In Fig. 3, this inverted Pareto-Lorenz coefficient is plotted for these shares, and using the share of the top 0.05% in the income of the top 0.5%. Since the distribution is only approximately Pareto in form, these coefficients do not coincide, but it may be seen that they move closely together.

A number of early researchers examined the fit to the South African data of the Pareto distribution. Leslie (1935, p. 279) found values for the inverted Pareto-Lorenz coefficient smaller than those found in European countries, suggesting less inequality at the top in South Africa. He reports a wide range, but our estimates suggest that the coefficient was between 2 and 2.5 from 1913 until after the Second World War. The coefficient then decreased, starting at the end of 1940s, indicating less inequality among those at the top of the distribution. From the end of the 1950s up to the 1980s, the inverted Pareto-Lorenz coefficient was broadly around 1.6. When we turn to the recent years, however, we see that β has gone up back to around 2 for the years since 2002. On this basis, the concentration of incomes at the top is returning to its pre-war level.

To this point, we have not discussed the very earliest estimates: those for the Cape Colony for 1903 to 1907. The Colony contained, in 1907, some 1.2 million tax units, compared with 2.7 million tax units in the Union in 1913. We have not been able to make any estimates of total income for the Colony, so that the results are presented in Appendix Table 14 in terms of shares-within-shares. The findings may be compared to those for the Union in 1914. The top 0.5% in 1907 had 70% of the total income of the top 1% cent, which is quite close to the 72% cent for the Union seven years later, but higher up the scale the incomes appear less concentrated.

5 Seeking to understand the evolution of top income shares in South Africa

There are many factors that could explain the picture we have described. Here we consider—in a preliminary way—only three; they do in fact correspond to those highlighted in the subtitle of Feinstein’s (2005) economic history of South Africa: conquest, discrimination and development.

5.1 Differing colonial legacy?

Our data on top incomes have the advantage of covering virtually the entire period since South Africa became, when the Union was formed, a self-governing dominion, and increasingly acquired further political powers, culminating in full independence. In this regard, its initial political history was similar to that of Australia, Canada and New Zealand, and it is therefore useful to draw a parallel. How far is their current distribution a reflection of the colonial past? Did South Africa have a different colonial legacy? In considering this question, a potentially important role is played by the differing sizes of the indigenous population: this is the subject of the next sub-section.

In Fig. 4, we compare the findings for the share of the top 1% cent in South Africa with those for the three other dominions and for the United Kingdom, the former colonial power, for the period for which we can provide a racial decomposition with the white population. It may be noted that the South African series starts the earliest. The comparison begins after the First World War. At that time, South Africa had the highest share of the top 1% cent of all the countries shown. The top 1% cent share in Canada was around 15% in the 1920s and the shares in Australia and New Zealand were close to 10%. As we have seen, the top shares fell in South Africa over the twentieth century, but the fall was less sharp than in the UK and North America.

Top 1% income share in UK, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. Sources: South Africa: Appendix Tables 5, 6 and 7, and authors’ calculations; United Kingdom: Atkinson (2005, 2007); Australia: Atkinson and Leigh (2007a, b); Canada: Saez and Veall (2007); New Zealand: Atkinson and Leigh (2007b, 2008); and Alvaredo et al. (2011–2015)

The share of the top 1% continued to be higher in South Africa in the post-war period. By the end of the 1970s, the shares had fallen to between 5 and 8% in the other countries, but in South Africa the share remained stubbornly at 10% or above. Subsequently, the gap began to narrow, as the top shares increased in the Anglo-Saxon countries after 1981, but South Africa is now tended in the same direction. The top share today is higher than in the UK and Canada, and much higher than in Australia and New Zealand. At some 20–25%, the top share in South Africa (Fig. 2) is essentially the same as in the United States. The initial differences, with South Africa having high top shares, appear to have been a persistent feature. In contrast, studying in detail at the series produced for these countries, it can be concluded that the distribution within the top 1% appears less concentrated in South Africa.

5.2 Apartheid

How much of this long-run difference can be attributed to the impact of racial differences? One major factor influencing the South African distribution of income is the racial composition of the population. From 1956 to 1987, the South African income tax statistics are published with a classification by race: white, Coloured, Asian and African (the latter not included for all years). For these years, we can see the make-up of the top income groups in Appendix Table 11.

We can consider the distribution for South Africa just among the white population. Appendix Table 12 shows estimates for the period 1956 to 1987, while for the years before 1955 (when the classification by race is not given) we take all taxpayers as being white. The orders of magnitude are clear from the following calculation. In 1956, the overall share of the top 1% was 17%. Since at the time the white population represented 20% of all tax units and constituted the vast majority of the top income recipients, this corresponded to approximately the share of the top 5% of the white population. Such an income share (17% cent for the top 5%, as Appendix Table 12 shows) would have placed them at that time well below the share recorded in 1956 in New Zealand (23.5%). Figure 4 also shows the share of the top 1% in South Africa among the whites. Therefore, tax data reveals a striking fact: income concentration has historically been rather similar (and even lower) within the white population in South Africa and within the total population in Australia, New Zealand or the UK.

In the mid-1950s, the top income groups were overwhelmingly white. In 1956, the top 5% consisted of 325,400 tax units, of whom 320,000 (98%) were white, 3700 were Asian, 1400 were Coloured, and 160 (0.05%) were classified as African (the term used in the official publication is “Bantu”). The composition did shift over the following thirty years: in 1987 the top 5% consisted of 782,000 tax units, of whom 708,000 were white, 24,300 were Asian, 30,300 were coloured and 19,200 were African (2.5%). The proportionate increase for Africans was large, by a factor of 120. This raises the question as to how this was possible during the apartheid era, and at a time when the relative incomes of Africans remained unchanged. The estimates of Leibbrandt et al. show that in 1956 the average per capita income of Africans was 8.6% of that for whites, and in 1987 the figure was virtually the same (8.5%) (2010, Table 1.1); over the same period, the relative per capita incomes of Asians went from 21.9 to 30.2%. The proportionate increase may have been large, but the actual numbers of non-whites was still small. Top incomes at the end of the 1980s remained highly concentrated by race: in 1987, whites were 90.6% of the top 5%, 96.7% of the top 1% and 97.5% of the top 0.1%. The last of these figures means that of the 15,600 tax units in this group, which began at about 100,000 rand per year, only some 400 were non-white. There was only limited change in the degree of dominance of the white population in the upper income groups over this period, as may be seen from Fig. 5.

What did top African taxpayers do? In 1965 (from the Report of the Secretary for Inland Revenue for the year 1966–67, Table 16), for example, there were 6100 African taxpayers in total (with positive incomes). Three-quarters (75.4%) received their income from employment; 13.2% were engaged in retail trade; and 8.0% had income from investments as their main source (largely interest). Of those African taxpayers in employment, 41% worked for state, provincial or local government, 24% in manufacturing or construction and 21% in services other than government. Therefore, high-pay government employment played a crucial role as income source for Africans at the upper end of the distribution.

The gap in the data between 1994 and 2001 prevents us from analysing the dynamics of top incomes in the crucial years immediately following the end of apartheid. Evidence from households’ surveys conducted in 1993, 2000 and 2008 (see Leibbrandt et al. 2010) indicates that inequality increased steadily, both within the whole population and within each racial group, especially among Africans. Van der Berg and Louw 2004, note that “rising black per capita incomes over the past three decades have narrowed the interracial income gap, although increasing inequality within the black population seems to have prevented a significant decline in aggregate inequality” (pp. 568–569). At the same time, poverty has remained virtually constant (or fallen slightly) over the same period. Both facts (increasing inequality and stable poverty) are consistent with the rising trend in top income shares recorded in our estimates for the period since 2002.

5.3 Development and natural resources

Alongside the colonial and political story, there was the development of the South African economy: “following the development of the diamond fields of Kimberley in the early 1870s, the South African economy achieved a hundred years of successful economic growth. … a relatively backward country, almost wholly dependent on a largely self-sufficient agricultural sector, was transformed into a dynamic, modern, capital-intensive economy” (Feinstein 2005, p. 200). How far can the time path of top shares in South Africa be due to its distinctive pattern of economic and social development? One tends to think of the role of gold production and minerals, but South Africa was not alone in its natural resource wealth. In fact, as noted by Feinstein, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa are “natural benchmarks”: “all four had achieved their initial growth in the nineteenth century by exporting primary products from their farms, forests, and mines, and were seeking in the twentieth century to develop their secondary industries with the aid of protective duties. All four were relatively small, and struggling to compete with larger, well-established industrial nations such as Britain and the United States” (2005, p. 132).

Figure 6 shows the changes over time in the share of the top 1% in each of these four countries indexed at 100 in 1921 for the four former dominions. As may be seen, the trajectories are remarkably similar for some 50 years. The top shares may have started at a higher level in South Africa as shown in the previous figure, but they fell at a very similar rate. There are undoubtedly differences between the countries, but they should be seen against the background of a common downward trend. Apartheid affected not only the internal distribution but also the external economic circumstances of South Africa. The mid-1980s saw the adoption of economic sanctions by the Commonwealth, by the European Communities and by the US Congress. The impact has been much debated, but we have noted that during this decade the top income shares in South Africa failed to rise, unlike those in other countries (this is the period after the vertical bar).

The country differences reflect also the differences in natural resource endowments. Figure 7 makes the comparison of the top 0.1% share against three former colonial territories: Zambia, Zimbabwe and India. Commonwealth countries had spikes corresponding to booms in particular commodities, such as that reflecting wool prices boom in Australia in 1950, or the post-war boom in South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe which benefited the rich disproportionately. In the case of South Africa, a key role is played by gold production and the gold price. South Africa dominated world gold production for much of the century: in 1913, it produced 40% of world production, rising to 50% by 1930, falling as a percentage as world production grew in the 1930s, but then rising to 60% in the 1960s—see Fig. 8. Production of gold in South Africa peaked in terms of tons in 1970 and after that fell both absolutely and relatively. Other minerals, notably coal and platinum, have increasingly taken the place of gold—see Fig. 9, which shows the value of sales at 2010 prices. The estimates of Katzen (1964, Table 9) show gold mining as accounting for 20%, and mining as a whole for 28%, of total geographical income of South Africa in 1911/12. By 1929/30, these percentages had fallen to 13 and 17%, but gold production recovered in the 1930s. The significance of gold production became less as manufacturing grew in the period after the Second World War, but it remained between 8 and 10% of total geographical income in the 1950s and early 1960s.

The distributional impact of gold, and other mineral production depends on the organisation of the industry. As observed by Feinstein, in the case of diamonds, “the day of the small independent digger… did not last long” (2005, p. 99). The process of amalgamation and consolidation “had effectively been accomplished by the late 1890s, with De Beers Consolidated Mines, under the control of Cecil Rhodes, in complete command of the industry” (Feinstein 2005, p. 99). In the case of gold, the nature of the deposits, which were in the form of particles embedded in quartz, mined at deep levels, meant that considerable investment and technical expertise were required. “Within a short time the industry was highly concentrated under the control of six giant mining and finance houses” (Feinstein 2005, p. 103). A substantial part of the investment came from overseas: “only through the continuous supply of capital from international capital markets was the development of the South African gold mining industry made possible” (Frankel 1967, p. 3). It was also the case that the industry depended on the employment of African workers from outside the Union, particularly in the earliest years. According to Read, workers from Portuguese East Africa were “the first to come in any large numbers when the Witwatersrand goldfields opened up” (1933, p. 398). However, the balance shifted and Katzen reports that “the percentage of Union to non-Union Africans rose from 43.8% in 1929 to 55.7% in 1932” (1964, p. 80).

The payments to foreign investors and to non-Union workers mean that a significant part of the industry value added did not enter the South African distribution of income. The low level of wages meant that the payments to non- Union labour were a small percentage: for the year 1952–53, the official estimate is that they accounted for £16 million, or 1.1% of total geographical income (Bureau of Census and Statistics 1954, p. 364). The payments to overseas investors were larger. According to Katzen, “approximately three-quarters of the dividends of the gold mines in 1930 went to overseas shareholders” (1964, p. 80). For the year 1952–53, the official estimate is that they accounted for £54.7 million, or 4% of total geographical income (Bureau of Census and Statistics 1954, p. 364).

These foreign factors clearly have to be taken into account when assessing the overall influence of the gold and mining industry. But the domestic distribution of income was not unaffected. Alvaredo and Atkinson (2010) show that the growth of the value of gold production and the growth of the average income of the top 0.1% move closely together, up to the 1970s. Mineral resources are a part of the story that needs to be further investigated using the long time series that we have constructed.

The evidence in this section seems to indicate that—despite the distinctive features of the South African historical experience—there is a surprising degree of commonality in the changes over the past hundred years. Local policies have undoubtedly been significant but have probably been more important in determining levels of poverty and the lower part of the income distribution. To explain the changes in top income shares, and the shape of the upper tail, we need to look at global as well as local forces.

5.4 Summary

Our estimates of top income shares provide hard evidence about the way in which income inequality in South Africa has changed over the past hundred years. At the formation of the Union, the top 1% received a fourth of total income. There was a fall in top income shares over much of the twentieth century, and incomes within the top groups became less concentrated up to the end of the 1980s. The dominance of the white population among top income receivers was slightly reduced. In recent years, however, top income shares have begun to rise again, justifying the widespread view that incomes in South Africa are highly unequally distributed.

6 Final remarks

The income tax publications offer a rich store of historical data about the evolution of top incomes in South Africa. Together with estimates for the earlier Cape Colony, the series span more than a hundred years. The construction of the estimates has been described at some length in order to underline their limitations, which mean that there are several potential sources of error. Nonetheless, they provide a basis for placing the recent data on inequality in its long-run historical context and furnish evidence about distributional change in earlier periods.

Our estimates track the evolution of top incomes over a long run of years, including the first half of the century when real incomes grew and the later decades that led to the collapse of apartheid. Top income shares were not stable. There were short-run movements and long-term trends. The share of the top 1% was halved between 1914 and 1993. The degree of concentration within the top 1% declined: people at the entry point in 1914 saw those above as having on average twice their income, whereas in the early 1990s the advantage was only some 1½ times.

The income tax data for 1956 to 1987 allow us to examine the racial composition of the top income groups. These were, unsurprisingly, overwhelmingly white, and the degree of dominance was little reduced. At the same time, the non-white groups increased their representation (in the case of Africans by a factor of 120), and this shows that some mobility took place during the apartheid years.

How far was South Africa different? We have compared top income shares in South Africa with three other former dominions: Australia, Canada and New Zealand, as well as with the UK. Immediately after the First World War, South Africa had the highest share of the top 1% of all the countries apart from the UK. Although top shares fell in South Africa, this fall does not appear to have been, at least up to 1980, at a faster rate than in the other dominions. The initial differences, with South Africa having higher top shares, appear to have been a persistent feature. Today, in terms of top income shares, South Africa ranks with the most unequal Anglo-Saxon countries. At the same time, as has been observed by earlier researchers, there is no greater concentration within the upper income groups.

The time series presented here will, we hope, provide the basis for detailed investigation of the impact of South African institutions and policies, past and present. But the similarity of the changes over time in top incomes across the four ex-dominions suggests that national developments have to be seen in the light of common global forces.

Notes

The publications were obtained from the (incomplete) collections in the British Library of Political and Economic Science (London School of Economics), the University of Cambridge Royal Commonwealth Society Library, the South Africa Parliament Library, the University of Cape Town Library, the Oxford University Libraries, the University of Harvard Libraries and the New York Public Library.

The two sources cannot be combined in any straightforward way, since the definition of taxable income differs in the two cases, and taxpayers may be ranked differently in the two sets of tables. After the abolition of the Super Tax, 2/3 of dividends were taxed through the Normal Tax.

We have not been able to get statistics for this period from the Treasury of South Africa or the South Africa Revenue Service.

The upper limit for the open top bracket assumes an inverted Pareto-Lorenz coefficient β = 2.5(α = 1.67) for 1963–1989, with a lower figure (β = 1.5 (α = 3)) for 1990–1993, on the grounds that the estimated coefficient in those years tended to fall in the upper income ranges.

Even though the number of taxpayers is well above 10% of the control total for the population, the series for the top 10% income share is not given from 1971 to 2007, as the resulting P90 value is usually very close to (and sometimes below) the threshold under which employees are only subject to PAYE, and not included in the statistics used here (these workers are not required to file a tax return).

Hut and poll taxes were imposed on the native population. In 1915, native taxes represented 9% of the Union tax collections, while the income tax (on persons and companies together) was 11%. In 1919 those figures were 5% and 30% respectively.

1 lb = 20 shillings; 1 shilling = 12 pence.

The feature of averaging taxable incomes over two years only applied to tax year 1916, when the Super Tax was levied on the mean income subject to Normal Tax and dividends that accrued over the period 1st July 1914–30th June 1916.

The Dividend Tax fell mainly on the profits of foreign capital invested in the Union through limited liability companies and served “to secure a higher rate of tax in respect of unearned income as distinct from income arising from personal exertion. It also enables tax to be recovered in bulk at the source”. (Report 1918–1919, p. 11). The Excess Profits Duty (starting income year 1916 and ending 30th June 1920) was a temporary tax levied on increased trading profits during the First World War.

“The whites who are occupied –i.e. have some definite income-earning occupation- numbered, according to the census of 1918 (omitting children under fifteen), 478,000, so that not one in eight of them, even, pays income tax” (Lehfeldt (1922), pp. 57–58).

For an account of the evolution of income taxation in the first years of the Union, see Kock (1924).

References

Alvaredo F, Bergeron A, Cassan A (2017) Income Concentration in British India, 1885–1946. J Dev Econ 127:459–469

Alvaredo F, Atkinson AB (2010) Colonial rule, apartheid and natural resources: top incomes in South Africa 1903–2007; CEPR DP 8155

Alvaredo F, Atkinson AB, Piketty T, Saez E (2011–2015) The world top incomes database. Published on line between 2011 and 2015

Atkinson AB (2005) Top incomes in the UK over the twentieth century. J R Stat Soc 168:325–343

Atkinson AB, Leigh A (2008) Top incomes in New Zealand 1921–2005: understanding the effects of marginal tax rates, migration threat, and the macroeconomy. Rev Income Wealth 54(2):149–165

Atkinson AB, Piketty T (2007) Top incomes over the twentieth century. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Atkinson AB, Piketty T (2010) Top incomes: a global perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Atkinson AB (2015) Top incomes in central africa: historical evidence. WID.world WP 4/2015

Atkinson AB (2007) The distribution of top incomes in the United Kingdom 1908–2000. In: Atkinson AB, Piketty T (eds) Chapter 4

Atkinson AB, Leigh A (2007) The distribution of top incomes in Australia. In: Atkinson AB, Piketty T (eds) Chapter 7

Atkinson AB, Leigh A (2007b) The distribution of top incomes in New Zealand. In: Atkinson AB, Piketty T (eds), Chapter 8

Banerjee A, Piketty T (2010) Top Indian incomes 1922–2000. In: Atkinson AB, Piketty T (eds) Top incomes: a global perspective, Oxford University Press, chapter 1

van der Berg S (2011) Current poverty and income distribution in the context of South African history. Econ Hist Dev Reg 26(1):120–140

van der Berg S, Louw M (2004) Changing patterns of south african income distribution: towards time series estimates of distribution and poverty. South African J Econ 72(3):546–572

Boshoff WH, Fourie J (2020) The South African economy in the twentieth century. In: Boshoff W (ed) Business cycles and structural change in south africa: advances in african economic, social and political development. Springer, Cham, pp 49–70

Bureau of Census and Statistics (1954) The net national income of the Union of South Africa, 1952–53. South African J Econ 22(3):353–364

Bureau of Census and Statistics (1956) National income of the Union of South Africa, 1954–55. South African J Econ 24(2):152–157

Chatterjee A, Czajka L, Gethin A (2020) Estimating the distribution of household wealth in South Africa. WID.world WP 2020/06

de Graaff J (1946) Fluctuations in income concentration, with special reference to changes in the concentration of supertaxable incomes in South Africa: July, 1915-June, 1943. South African J Econ 14(1):22–39

de Kock MH (1924) An analysis of the finances of the union of South Africa. Juta & Co. LTD., Cape Town and Johannesburg

Dollery B (2003) A history of inequality in South Africa, 1652–2002. South African J Econ 71(3):595–610

Fedderke J, Simkins C (2012) Economic growth in South Africa. Econ Hist Dev Reg 27(1):176–208

Feinstein CH (2005) An economic history of South Africa, conquest, discrimination and development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Finn A, Leibbrandt M, Woolard I (2013) What happened to multidimensional poverty in South Africa between 1993 and 2010? Working Paper 99, Southern African Labour and Development Research Unit

Frankel SH (1941) Consumption, investment and war expenditure in relation to the South African national income. South African J Econ 9(4):445–448

Frankel SH (1943) Consumption, investment and war expenditure in relation to the South African national income. South African J Econ 11(1):75–77

Frankel SH, Herzfeld H (1943) European income distribution in the Union of South Africa and the effect thereon of income taxation. South African J Econ 11(2):121–136

Frankel SH, Neumark SD (1940) Note on the national income of the Union of South Africa, 1927/28, 1932/33, 1934/35. South African J Econ 8(1):78–81

Frankel SH (1944) An analysis of the growth of the national income of the Union in the period of prosperity before the War. South African J Econ 112–138

Franzsen DG (1954) National accounts and national income in the Union of South Africa since 1933. South African J Econ 22(1):115–126

Franzsen Commission (1968) Taxation in South Africa: First Report of the Commission of Enquiry into Fiscal and Monetary Policy in South Africa, Government Printer, Pretoria

Hellmann E (ed) (1949) Handbook on race relations in South Africa. Oxford University Press, Cape Town

Katz Commission (1995) Third Interim Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Certain Aspects of the Tax Structure of South Africa, The Government Printer, Pretoria

Katzen L (1964) Gold and the South African economy, A. A. Balkema, Cape Town

Klasen S (1997) Poverty, inequality and deprivation in South Africa: an analysis of the 1993 SALDRU survey. Soc Indic Res 41(1–3):51–94

Klasen S (2005) Measuring poverty and deprivation in South Africa. Rev Income Wealth 46(1):33–58

Kuznets S (1953) Shares of Upper income groups in income and savings. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York

Lehfeldt RA (1922) The National Resources of South Africa. University of the Witwatersrand Press, Johannesburg, and Longmans Green & Co., London

Leibbrandt M, Woolard I, Woolard C (2009) A long-run perspective on contemporary poverty and inequality dynamics. In: Aron J, Kahn B, Kingdon G (eds) South Africa economic policy under democracy, vol 10. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Leibbrandt M, Woolard I, Finn A, Argent J (2010) Trends in South African Income Distribution and Poverty since the Fall of Apartheid, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers n. 101

Leslie R (1935) The effect of the abandonment of the gold standard on the distribution of incomes in South Africa. South African J Econ 3(2):279–280

Leslie R (1936) The change in the distribution of incomes in south africa after the abandonment of the gold standard. South African J Econ 4(1):122

Leslie R (1937) Distribution of incomes in South Africa. South African J Econ 5(1):95

Margo Commission (1987) Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Tax Structure of the Republic of South Africa, 20 November 1986, The Government Printer, RP34

McGrath MD, Whiteford A (1994) The distribution of income in South Africa, Human Science Research Council, Pretoria

McGrath MD (1983) The distribution of personal income in South Africa in selected years over the period from 1945 to 1980, Ph D thesis, University of Natal, Durban

National Treasury and South African Revenue Service (2009) 2008 Tax Statistics, Department of National Treasury, Pretoria

Nattrass N, Seekings J (1997) Citizenship and Welfare in South Africa: deracialisation and Inequality in a Labour-Surplus Economy. Can J African Stud 31(3):452–481

Nattrass N, Seekings J (2011) The Economy and poverty in the twentieth century. In: Ross R, Mager A, Nasson B (eds) The cambridge history of south Africa. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 518–572

Orkin FM, Lehohla PJ, Kahimbaara JA (1998) Social transformation and the relationship between users and producers of official statistics: the case of the 1996 population census in South Africa. Stat J United Nations 15(3–4):265–279

Read CL (1933) Presidential address: the union native and the witwatersrand gold mines. South African J Econ 1(4):397–404

Report of the Commissioner of Taxes for the Year (1904–5) G.32, Cape Times Limited, Government Printer, Cape Town

Saez E, Veall M (2007) The evolution of high incomes in Canada, 1920–2000. In: Atkinson A, Piketty T (eds) Chapter 6

Samuels LH (ed) (1963) African studies in income and wealth. Bowes and Bowes, Cambridge

Samuels LH (1963) The uses and limitations of national economic accounting, with special reference to South Africa. In: Samuels LH (ed), pp 162–181

Sonnabend H (1949) Population. In: Hellmann E (ed), Chapter 2

South African Reserve Bank (2005) South Africa’s National Accounts 1946–2004. An Overview of Sources and Methods, Supplement to the South African Reserve Bank Quarterly Bulletin, June

South African Revenue Service (2009) Comprehensive guide to capital gains tax (issue 2)

Stadler JJ (1963) The gross domestic product of South Africa 1911–1959. South African J Econ 31(3):185–208

Terreblanche S (2002) A history of inequality in South Africa, 1652–2002. University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg

United Nations (1994) The sex and age distribution of the world populations. United Nations Population Division, New York

Wilson F (2011) Historical Roots of Inequality in South Africa. Econ Hist Dev Reg 26(1):1–15

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are most grateful to the following for their help in obtaining the data used in this paper: Cristina Da Silva and Cecil Morden (Treasury of South Africa), Deon Breytenbach (South African Revenue Service), Niek Schoeman (Bureau for Economic Policy and Analysis, University of Pretoria), Louis van Tonder, Mathando Lukoto and Jean-Marie Hakizimana (Statistics South Africa), Laureen Rushby and Fiona Jones (Chancellor Oppenheimer Library, University of Cape Town) and Natalia Pierce (Bodleian Library). They are not to be held responsible in any way for the use made of the information supplied. We are also indebted to Murray Leibbrandt and Ingrid Woolard for comments and discussions. We acknowledge financial support from the Institute for New Economic Thinking, and the ESRC-DFID joint fund (ES/I033114/1). Further details about the historical context, the tax system, and the sources and methods employed, are given in an earlier working paper published as CEPR DP 8155 (Alvaredo and Atkinson, 2010).

Tony sadly passed away on 1st January 2017. The core of this version of the paper (based on a project that started in 2008, in the context of a wider research programme on income concentration in the British and French former colonial territories) was prepared during the summer of 2016.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 The income tax in South Africa

Prior to the formation of the Union of South Africa, the taxation of incomes and profits (apart from mining profits) was enforced in the Cape Colony and in Natal. The Additional Taxation Act, 1904, introduced income taxation in the Cape of Good Hope, both on companies and persons, subjecting to tax for the first time “all taxable incomes arising or accruing during the twelve months ended 30th June 1904, exceeding £1000% per annum” (Additional Taxation Act, 1904, Sect. 50). The incomes of married women without community of property were assessed individually. Taxable income referred to employment income, including employment in the public service, rents of all property in the Cape Colony, dividends and interest, and “any other source of income whatever arising or accruing in Cape Colony” (Report of the Commissioner of Taxes for the Year 1904–1905, p. 42). In 1903, there were 2193 taxpayers.

The Income Tax Act, 1908, regulated income taxation in Natal, but was short lived. On the establishment of the Union in 1910, the Natal income tax was abolished, while that in the Cape was allowed to lapse, as it was not re-enacted after 1909. By 1914, the need for additional revenue had rendered it necessary for the Union government to incorporate an income tax into its fiscal system. The Income Tax Act, 1914, established the income tax (later called the Normal Tax) in all the territory of the Union. “It was estimated that there would be 5000 taxpayers. The number of assessments made was 5742” (5140 individuals and 602 companies), Report on the Working of the Income Tax Act, 1914, for the Year ended 30th June 1915, p. 2.Footnote 8

The Union income tax was based on personal reporting. The tax had a limited scope, as provision was made for the exemption of all incomes under £1000, as well as for a fixed abatement of £1000 in respect of all taxable incomes. Individuals were exempted from taxation on dividends and debenture interest received from companies that had paid the income tax or the mining profits tax. The maximum tax rate was, in 1913–1914, 1 shilling and 6 pence per pound of taxable income for those individuals with taxable incomes above £24,000.Footnote 9 As a result of fiscal necessity due to the First World War economic conditions, the exemption and the abatement were reduced to £300 for income year 1914–1915, no abatement was allowed for taxable incomes above £24,300, family-based allowances were introduced, and the maximum tax rate was increased to 2 s (Act No. 23 of 1915). For tax year 1916, a super tax was also levied on the annual incomes of individuals which exceeded £2500 averaged over the two 1914 and 1915 (and Act No. 35 of 1916), with a maximum rate of 3 s in the pound.Footnote 10

A reform through the Income Tax Consolidation Act, 1917, re-structured income taxation around a main tax, the Normal Tax, supplemented by the Super Tax (in force until income year 1958–1959) and by other levies on incomes arising in the Union.Footnote 11 Taxable income was all income, other than exempt income, less all allowable deductions. Dividends were not taxed under Normal Tax but subject to Super Tax. Interest on Union Loan Certificates and Savings Levy Certificates were exempted as well as interest on small savings accounts and on some treasury bonds up to a threshold. A distinction was introduced between married and single persons by granting different abatements (for married individuals it was initially £300 a year, subject to the taxable income not exceeding £24,300, while for single persons it was reduced by £1 for every £ of taxable income in excess of £300). It remained the case that the tax was paid by only a small minority of the population.Footnote 12

The Super Tax was paid by an even smaller number of people. It was an additional tax on incomes exceeding £2500 (limit lowered to £2000 since income year 1940, and to £1775 since income year 1943), applying only to individuals who were resident or carrying business in the Union. The abatement of £2500 was subject to a reduction of 10 s. for every pound by which the supertaxable income exceeded £2500, i.e. no abatement was applicable to incomes above £7500. Its main purpose was to tax the top income resident at a higher rate than the non-resident and thus reduce the liability of double taxation. The sources of income from which the Super Tax was derived were the same as for the Normal Tax, plus dividends.Footnote 13 Since income year 1931 the Super Tax was extended to private companies and, where a number of private companies were controlled by a single person, all their income was aggregated for the purpose of determining the amount of Super Tax payable. The Super Tax survived until income year 1958 (with some changes under the provisions of the Income Tax Act of 1941), when it was provided that a fraction of dividends received (ranging from 0% for taxable incomes below R2,600, to 66.6% for taxable incomes above R4,600) would be included in the Normal Tax base.

From 1959, block rates took the place of the progressive-rate formula that had been applied before. There was also a change in the year of assessment. Until income year 1961–1962, the year of assessment covered the twelve months between 1st July of year t and 30th June of year t + 1. Since income year 1963–1964, the assessment year covers the twelve months between 1st March of year t and the end of February of year t + 1. Due to the change in timing, there was a shorter transitional income year of eight months between 1st July 1962 and 28th February 1963, for which no income tabulations were produced. This coincided with the transition to the pay-as-you-earn system of tax collection.

In the twenty-first century, the Personal Income tax is the government’s main source of income and is still levied in terms of the Income Tax Act of 1962. Tax is applied on taxable income that, in essence, consists of gross income less exemptions and allowable deductions. More than 95% of the tax comes from a pay-as-you-earn schedule. The Standard Income Tax on Employees (SITE) is not a separate kind of tax but a payment towards the employee’s income tax liability: as it is the case in many countries, employees receiving only labour income below a given threshold are not required to file a tax return, as SITE is their full and final liability. Taxed income includes labour income (cash remuneration, cash allowances and non-cash fringe benefits), pensions, capital income (interest from bank accounts above a given threshold, dividends from foreign companies; dividends from South African to varying degrees), business income and rents. One fourth of net capital gains are today included in the definition of income. In fact, although capital gains taxation has been broadly discussed over the last forty years (see South African Revenue Service (2009), Franzsen Commission (1968), Margo Commission (1987), Katz Commission (1995)), it was not introduced until 2001 through the Taxation Laws Amendment Bill (B17-2001) and the Taxation Law Amendment Act.

Both the Normal Tax and the Super Tax were originally levied on the tax unit, treating the married couple as one unit. In the late 1980s, a process of eliminating gender discrimination started. In 1988, the salaries of married women only subject to the Standard Income Tax on Employees (SITE) began to be taxed separately; this affected mainly low earning women. In 1990, the incomes of married women became subject to tax separately from her husband’s income. Although taxed individually, until 1994 women faced a higher rate than their husbands’: three different tax schedules affected married “persons”, unmarried persons and married women.

The Income Tax Act defines a spouse in relation to any person as a partner in marriage, customary relationship or union recognised as a marriage; the definition also includes a same-sex relationship. For spouses married in community of property, income received by spouses is treated as being received in equal shares by each spouse; however, a salary from a third party is treated as being the income of the spouse who receives that salary, as well as benefits from pension, provident and retirement annuity funds; income earned from carrying on a trade jointly accrues to each partner according to the agreed profit-sharing ratio. Since 1995, a single tax rate structure is applicable to all individuals irrespective of gender or marital status.

1.2 Sources of income tax tabulations

The sources of income tax tabulations are listed in detail in Table 1. There are the following gaps in coverage:

-

1.

1951 and 1952, as a result of arrears of wartime work, no publication between Report 1951–52 (published in 1953) and Report 1953–56 (published in 1957);

-

2.

1960 and 1962 as a result of the introduction of PAYE;

-

3.

1966, 1968, 1970, 1973, 1976 and 1977;

-

4.

1994–2001.

1.3 Control totals for tax units and individuals

The sources for the three steps identified in the text are set out in Table 2, covering (1) total population (described in Sect. 3), (2) the age structure of the population and (3) marital status for women.

Data on the population by age has been interpolated from yearly figures obtained from publication P0302 (Table 6) for 2006, the censuses for 2001 (Table 4.3) and 1996 (Table 2.16), and data from the United Nations (1994), which give the age composition at 5-year intervals from 1990 back to 1950.

For the period prior to 1990, the number of tax units is obtained from the number of people aged 15 and over minus the estimated proportion who are married women. The ratio of married women to those aged 15 and over is taken from the census of population for those years where all races are covered: 1911, 1921, 1936, 1946, 1951, 1960, 1970, 1980 and 1991. It is simply assumed that the same proportion applies for the two “missing” groups: the under-enumerated and the TBVC states. The ratio is linearly interpolated.