Abstract

Historical rates of return on investments have received increasing scholarly attention in recent years. Much literature has focused especially on colonies, where institutions have been argued to facilitate severe exploitation. In the present study, we examine the return on investments in an Asian colony, British Malaya, from 1889 to 1969 for a large sample of companies. Our results suggest that the return on investments in Malaya might have been among the highest in the world during the period studied. Nevertheless, this finding fits badly with theories of imperial exploitation and can only to a limited extent be explained by a higher risk premium. Instead, we argue that the main driver of the very high return on investments in Malaya was rather the substantial rise in global market prices of the output of the two main sectors of the Malayan economy, rubber and tin. The way that the process of decolonization unfolded in Malaya did, furthermore, not lead to any major nationalization of foreign-held assets, and did thereby not disrupt the return on investment in the region in the same way as decolonization did to the return on investment in some other colonies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Colonies have long been argued to have enabled investors to make particularly high profits, also known as ‘super-profits’, by allowing unusually severe exploitation. Recent research in the field of economic history has revived this concept. New evidence suggests that colonial investments paid a premium on the return thanks to colonial institutions favourable to the European investors. Yet, the previous literature in the field has focused for the most part on African colonies. One rare exception is a recent study of the Netherland’s Indies (current-day Indonesia) for a small sample of companies over a couple of decades in the mid-twentieth century.

In the present paper, we contribute to the debate on colonialism and return on investment with a study of another tropical Asian colony, British Malaya. Our study spans over a long period, from 1889 to 1969, and relies on a comparatively large sample of companies. The sample is dominated by investments in two key sectors of the colonial economy of British Malaya: tin and rubber. Our results show that the return on investment in Malaya was substantially higher than the return in any other part of the world for which data are available during the period under investigation. These results, we conclude, cannot be explained by exploitative labour regimes alone. In fact, the return on investments were at its highest at the end of the period under study, when the labour regime was much less repressive than it had been during the early colonial period. Partly, the high return can be explained by the fact that it was also a high-risk environment for investors. The volatility of return in British Malaya was rather high compared to regions with more diversified and mature investments objects. The most important factor behind these results, we argue, is, however, that the world market price of tin and rubber had a substantial impact upon the profitability of the ventures. The high (but volatile) prices can, in turn, be explained by rising demand from industrializing economies, and particularly for military purposes. Finally, as the process of decolonization in Malaya led to no nationalizations of foreign businesses during the period under study, decolonization did not reduce the average return on investment in the colony at the very end of the colonial period, as it did in some other colonies.

2 Research problem

At the end of the nineteenth century, capital exports from Europe increased drastically. Many theories have been formulated to explain why such large amounts of capital were exported, and the patterns of where to it was exported. One of the key theories, suggested, for example, by the radical theorist John Hobson and later picked up by several Marxist thinkers, asserted that colonies were a crucial recipient of European capital investments during the age of high imperialism. Some would furthermore argue that colonies were merely a vent for surplus capital in Europe, countering any tendencies towards falling marginal return on investment on the domestic market. Others would put forth the stronger argument that the rate of return on investment was systematically higher in colonies than it was elsewhere due to economic exploitation of the colonies, and in particular of the local labour force (see Rönnbäck and Broberg 2019, chap. 3 for an overview of the discussion). The discussion has been re-invigorated in recent years by new research making just this particular claim, arguing, for example, that the high return on investment in the Netherlands Indies is attributable to “systematic labour repression” in the colony (Buelens and Frankema 2015; see also Buelens and Marysse 2009).

In recent years, numerous studies have delved into the historical rates of return on investment in various parts of the world. In 2002, Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton published the book Triumph of the Optimists (Dimson et al. 2002), where they examined the return on investments in a number of developed countries around the world throughout the twentieth century. They showed substantial differences in the rate of return between countries, as well as over time. They also show why the standard deviation of returns—i.e. volatility—is an important measurement of risk when comparing different countries or regions over time (Dimson et al. 2002, 54). Other studies have focused on the return on investment in developing countries. This is especially the case for Africa, where research has investigated the return on investment especially during the colonial era. Frans Buelens and Stefaan Marysse have studied the return on investments in Belgian Congo under colonial rule, from 1889 to 1960, and argued that the return on investments were indeed higher there than in Belgium during the same period (Buelens and Marysse 2009). Klas Rönnbäck and Oskar Broberg have analysed the return on British investments in some 700 companies operating in colonial Africa from 1869 to 1969. In contrast to Buelens and Marysse, they find that return on investment was only slightly higher in colonial Africa than in other parts of the world over the whole period under study, although the return on investment varied considerably over the time, with higher return on investing in colonies during specific periods (Rönnbäck and Broberg 2018, 2019).

Despite the recent surge of interest in the study of return of investment across the globe, there is only one previous study focusing on an Asian colony—Frans Buelens and Ewout Frankema’s study of the return on investments in 17 companies operating plantations in the Netherlands Indies during the period 1919–1958. They find that the rate of return on investment was substantially higher than the return on domestic investments in the Netherlands during the interwar period. Their interpretation of this finding is as support of the theory of colonial labour exploitation leading to higher return on investment (Buelens and Frankema 2015).

Neighbouring on the Netherlands Indies was British Malaya. Numerous scholars have suggested that the investments in this colony generally were highly successful and that investors could make high profits from investing there (Bach 1976, 467; Thoburn 1977, Tables 5.9, 6.13, 6.18, 6.20; Khor 1983, 17–18, 57–58, 154–55; van Helten and Jones 1989, 159, 167; Lindblad 1997, 68; 1998, 47, 86–87; Drabble 2000, 60, 116; Lees 2017, 171). However, these claims are made on highly anecdotal evidence—e.g. dividend data for one or a few selected companies during particular years. In their recent research, Dimson, Marsh and Staunton also include data on the historical rates of return on investments in Malaysia, but only from 1964 onwards (Dimson et al. 2019, 11). So far, no systematic attempt to study the return on investment in British Malaya has been undertaken over the longer run (most importantly including the colonial period of Malayan history) and for a large sample of companies. Our study, therefore, attempts to contribute to filling this research gap. The research questions that we aim to answer are: how high was the return on investment in British Malaya, and how did it change over time? We conclude by discussing how our results can be interpreted in relation to the theoretical debates on the return on investment in colonies.

3 Historical context

Prior to our period of investigation, Malaya had already been a key node in the Indian Ocean trade for several centuries. Despite being a comparatively small colony from the perspective of the imperial power Britain, it was, nonetheless the fifth most populous of Britain’s tropical colonies by the mid twentieth century (Havinden and Meredith 1996, table 1.2).

The colonization of Malaya by the British had been gradual, spanning over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. First steps towards the colonization of the region had been taken already in the early nineteenth century by the British East India Company. The areas controlled by the Company formed the Straits Settlement, which was administered as a Crown Colony from 1867 to 1942. Other parts of the Malayan peninsula were also colonized over time and became known as the Federated Malay States, administered by the British Crown, while the remainder of the peninsula constituted the Unfederated Malay States. North Borneo, on the other hand, was colonized and administered by the North Borneo Chartered Company until the 1940s. From the merger of these diverse territories, the Federation of Malaya was born in 1948. In 1957, the federation achieved political independence from Britain, and six years later formed the Federation of Malaysia (Allen and Donnithorne 1957, 40–41; Tregonning 1958, 26–27; van Helten and Jones 1989, 159; Havinden and Meredith 1996, 39–40; Drabble 2000, 28–32; Tajuddin 2012, 30–42; Lees 2017, 4–7).

Although economic factors may not have been the prime motive behind the colonization of Malaya, “the British, by a typically unplanned act of serendipity, had stumbled upon a treasure chest, as Malaya became financially and commercially important in the twentieth century”, as Nicholas White put it (White 1999, 176). As was the case in so many other colonies, Malaya developed into an exporter of raw materials. In North Borneo it was the export of timber and tobacco, and eventually also of rubber (Tregonning 1958, 82–91; John and Jackson 1973). On the Malayan peninsula it was mostly tin and rubber (van Helten and Jones 1989, 161). During the nineteenth century the Malayan economy, including rubber and tin production, was dominated by Chinese entrepreneurs (Parmer 1960, 7; Wong 1965, 19–20; Yip 1969, chap. 2). By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, however, European capital—and in particular British—started to pour into the region. During the early decades of the twentieth century, Malaya had become one of the top global recipients of British investments in the raw materials-sector (Stone 1999, table 42). Virtually all of these investments were targeted at either the tin or the rubber sector, to the extent that in 1930 93 per cent of all British investments in Malaya were in either of these two sectors (van Helten and Jones 1989, 163). The inflow of foreign investments were enabled by the comparatively liberal investment regime that the colonial authorities operated in Malaya (Lindblad 1997, 65; 1998, 84; Twomey 2000, 138–39). The Malayan economy thereby became the fastest growing economy in all of South-East Asia, with GDP more than doubling between 1870 and 1929 (Booth 2008, Table 1). Despite the rapid growth, industrialization was negligible and the colony remained an exporter of raw materials dependent upon the importation of capital goods (Huff 2002).

By the late nineteenth century, Malayan tin mining experienced a considerable investment boom with several new flotations on the London Stock Exchange (Wong 1965, 124–25), although several of these early ventures failed. At this time, Chinese entrepreneurs could mine large surface deposits more competitively than Europeans could by using labour-intensive mining techniques. Europeans not only did not have major technological advantage yet, but often lacked access to enough capital to mine tin competitively (Wong 1965, 137–40; Lim 1969, 50; Hennart 1986, 133–34; van Helten and Jones 1989, 165; Drabble 2000, 56). During the early twentieth century, Chinese tin mining companies began experiencing problems when trying to recruit coolie labourers from China. Concurrently, most of the surface deposits had been depleted, and more capital-intensive forms of mining became necessary to survive in the competition. Dredging and gravel pumping became the two most common methods of mining tin in the region during the period (Thoburn 1977, table 5.2). European companies were better able to introduce such labour-saving, capital-intensive, technologies thanks to their greater access to the London financial market, a factor that can explain why European entrepreneurs were able to gradually increase their market shares (Wong 1965, 203–30; Lim 1969, 50; Yip 1969, chap. 3; Hennart 1986, 135–37; van Helten and Jones 1989, 165; Drabble 2000, 56). The development of capital-intensive mining would, however, probably not have occurred without the additional factor of high real prices for the tin output (Matthews 1990).

Rubber plantations were the second major sector to develop in colonial Malaya. Similar to tin mining, the sector had been dominated by Chinese entrepreneurs in the nineteenth century. Some attempts by Europeans to establish rubber plantations were first undertaken in the 1890s (Drabble 1973, 20–21). In some cases, early Chinese and British enterprises developed in symbiosis (Tuan 2010). A major rubber boom, due to a drastic increase in the demand for rubber to feed the growing automobile industry among others, started around 1905. This led to a wave of new company flotations to establish plantations in Malaya (Allen and Donnithorne 1957, 111–12; Lim 1969, 75; Stillson 1971; Drabble 1972; 1973, 30–34). Plantations that previously had been devoted to other crops, such as sugar, were hastily converted into rubber (Lees 2007). Malaya quickly became one of the world’s leading plantation economies in terms of acreage (Christopher 1985, table IV). The following years would then be highly volatile for the rapidly growing sector. A new, and even more drastic, boom came in 1909–1910, yet by the First World War, the rubber sector had experienced a first major slump. During the war, attempts were made to impose voluntary restrictions on rubber exports in order to counter the depressed prices (Drabble 1973, 106–7, 138). Further slumps occurred in 1920–22, largely as a consequence of falling world demand for rubber, which impacted hard upon the Malayan economy (Parmer 1960, 8–10; Drabble 1972, 258; 1973, 169; van Helten and Jones 1989, 171–74; Drabble 2000, 122–24). In response, a scheme was imposed between 1922 and 1928 with the aim to increase and stabilize rubber prices by restricting the output of rubber in Malaya, the so-called Stevenson Restriction Scheme (Allen and Donnithorne 1957, 121; Lim 1969, 76). At the same time, the industry grew increasingly concentrated, with a few companies owning a growing number of plantations in the colony (Lindblad 1998, 85).

Several factors contributed to the large foreign investments in the Malayan economy during this early part of the colonial period. Pax Britannica, the stability and security that the British Empire provided, undoubtedly made many investors more willing to invest in the colony (Drabble 1974, 201; Hennart 1986, 132; Harvey and Press 1990, 112; Lindblad 1997, 63). Investments in infrastructure created further incentives for investments by lowering trade costs. It was during the nineteenth century that Singapore developed as a major trade entrepôt, a factor that contributed to the development of trade on the rest of the Malayan peninsula (Jones et al. 1993, 64, 139). The construction of a railroad network on the Malayan peninsula began in 1885, and by 1899 the railway connected all key mining areas in the peninsula with the ports. In order to take advantage of the new transport infrastructure, rubber plantations often came to be established along the newly developed railway network (Yip 1969, 115–16; Latham 1978, 19; Drabble 2000, 82–88). The connection of both Penang and Singapore to the global telegraph network in 1870 furthermore made communication between company boards in Europe, and the companies’ local representatives easier and faster (Latham 1978, 34; Lees 2017, 31).

The institutional setting provided substantial support particularly to European planters, in the form of land alienation policies. In the 1890s, the colonial regime had taken over the control of all matters related to land alienation in Malaya (Tajuddin 2012, 38; Lees 2017, 40–41). This was at a time when land in Malaya turned from being an abundant resource to being scarce (Jomo 1986, 86). As land became scarce, competition for all unalienated land grew increasingly fierce. From the early twentieth century onwards, the colonial government in Malaya systematically prioritized Europeans applying for land before all other applicants, in particular before Malayan smallholders. As a result, much of the best and more fertile land came to be appropriated by European planters (Jomo 1986, 199; Drabble 1973, 74; 2000, 64; Lees 2017, 176).Footnote 1

The colonial government further supported European investors by increasing the supply of labour at a low cost. The remarkable growth rates experienced in rubber planting and tin mining in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries led to a rapidly growing demand for labourers (Rasiah 1995, 55). Malayan workers were considered to be too expensive by European entrepreneurs, so attempts were made to recruit cheaper indentured servants from India, China and Java, with the colonial government acting as an intermediary in the importation of the “coolie” labourers (Parmer 1960; Chai 1964, chap. 3; Tajuddin 2012, 56–61; Lees 2017, 42–47; van Helten and Jones 1989, 171–74; Ramasamy 1992). Other labour policies were aimed at further favouring the interest of the employers, for example, by controlling the movement of labourers so that they could not seek employment for anybody else than the one who had recruited them in the first place. Labourers who did not comply with their contract could be sent to jail (Wong 1965, 116; Lees 2017, 89–93). Furthermore, numerous leading planters formed a cartel on the labour market aimed at reducing, or at least limiting, the wages paid to workers with the tacit acceptance of the colonial government (Parmer 1960, 173).

The Great Depression hit Malayan export economy hard once again, particularly the rubber plantations as rubber prices plummeted to very low levels. Concurrently, tin prices took a downfall due to excess production that impacted on the profitability of mining companies (Lim 1969, 78–79; Lindblad 1998, 15; Drabble 2000, 130). Malayan producers reverted to the establishment of international cartels aimed at increasing prices by limiting output. In the 1930s the International Tin Cartel and the Rubber Regulation Agreement were founded. Despite their aim being to raise the profitability of these industries, both had only very limited success (Hillman 1988, 1997; Drabble 2000, 130–31; Hillman 2010; Allen and Donnithorne 1957, 125; Parmer 1960, 10; Lim 1969, 80).

During the Second World War, from the late 1941 to 1945, the Malayan peninsula was occupied by the Japanese. Before abandoning the colony to the Japanese forces, the British practiced a “scorched earth” policy, destroying capital that had been invested, particularly in the tin mines. Rubber planters would also suffer from the occupation, as the Japanese demand for rubber was far lower than the output from the Malayan plantations (Bauer 1948, 341; Lim 1969, 61; Yip 1969, 287; Drabble 2000, 149–52). In the post-war years, recovery was comparatively quick for the rubber plantations thanks to the limited degree of capital destruction in the plantation sector, while it took longer for tin mining since capital destruction in this sector had been more extensive (Drabble 2000, 156). In the years following the war, Malayan producers did also receive some war compensation for capital destroyed during the war (Yip 1969, 307). Although the rubber sector was able to recover quickly, in the post-war economy it faced mounting competition from synthetic rubber, which had been developed during the war (Lim 1969, 84–85). Tin was, in contrast, in short supply after the war. In order to boost prices, the colonial government imposed a guaranteed price. The price was set so high that numerous investors anticipated substantial future profits, which boosted the stock prices of several tin mining companies (White 2015, 171).

In 1948, an armed insurgency arose in Malaya. The insurgents were mainly active in remote, rural areas of the colony. The tin-mines were particularly vulnerable against attacks due to their geographical location. Not only did the insurgency affect already established tin mines, but it made it hard, if not impossible, to develop new mines in the affected regions (Drabble 2000, 153; White 2015, 172, 186–88). The “Emergency”, as the colonial authorities dubbed the insurrection, was met with fierce repression from the colonial government, and by the mid-1950s it became clear that the colonial government was winning the battle (White 2004, 97; Tajuddin 2012, 134–38).

Despite the insurrection, the colonial government continued to support European entrepreneurs through its labour policies, even in the late colonial era. Although slightly more liberal than it had been earlier on, so that actions that were criminalized in the late nineteenth century by this time had come to be accepted, labour policies in the main continued to favour the employers’ interests (Lees 2017, 192). Trade unions were not recognized by the colonial authorities in Malaya until the 1940s, and even once recognized in principle, the colonial authorities actively tried to limit the degree of unionization, for example, through the establishment of government-controlled yellow unions (Lim 1969, 120; Jomo 1986, 235–36). In addition, attempts to organize collectively were often forcibly repressed by the government still in the 1940s (Ramasamy 1992).

From the 1950s onwards, the Malayan economy experienced a series of three ‘big pushes’ (Lim 1969, 8–18). The first ‘push’ followed the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, when prices for several commodities, including tin and rubber, increased. Tin prices, in particular, skyrocketed as tin was considered a strategic commodity for the war effort (Drabble 2000, 160–61; White 2015, 174). In the aftermath of the Korean War, the International Tin Agreement was successfully established, entering into force in 1956. This event—together with the continuation of the United States strategic stockpiling of tin—contributed to a second ‘push’ (Smith and Schink 1976; Gilbert 1977; 1996; Drabble 2000, 230; White 2015, 185). The gains from this ‘push’ were short-lived, and the tin mining sector experienced an economic crisis in the following years. As a result, several Malayan mines were closed in an attempt towards rationalization (White 2015, 185–89). A third push came some years late, and positively impacted on the prices of both tin and rubber, among other commodities (Lim 1969, 8–18).

At this stage, however, the process of decolonization was well underway in Malaya. In 1946, the chartered rule of North Borneo finally ended (Tregonning 1958, 222). By 1957, the entire Malaya had achieved political independence from Britain. The government of the newly independent country chose not to challenge any of the foreign-owned companies until the 1970s, leaving British companies in control of much of the Malayan economy long after independence (Lindblad 1998, 106–8; White 1994, 251; 2004, 2). All in all, in the post-war economy rubber and tin emerged as the two leading dollar-earners for the British empire, especially with the rise of the exportation of these commodities to the United States (White 2015, 171; Sutton 2016).

4 Methods and data

To study the financial performance of individual companies is often problematic, as publicly reported figures on company profits might be misleading for several reasons. For example, the company might have an interest in showing smaller profits for tax-reasons, the board might prioritize re-investment and growth before profits and the leading owner’s might have reasons to minimize profits in order to strengthen their own position vis a vis the financial market.

In recent years, several studies in the field of financial history have therefore opted for studying the return on investment—i.e. to analyse financial performance from the perspective of the investors in the companies rather than from company declared profits (Edelstein 1970, 1976, 1982; Dimson et al. 2002; Buelens and Marysse 2009; Buelens and Frankema 2015; Grossman 2015; Rönnbäck and Broberg 2019). By studying the return on investment, we implicitly assume that contemporary agents on the financial market were reasonably well informed about the company’s activities over the long run, and therefore in a position to judge the value of the company. This would thus translate into changes in the market price of the company’s shares. Such changes constitute, however, only one part of the total return on investing in the company. Another part is dividends to shareholders. Hence, if investors were reasonably well informed about the company’s activities, the total return on investment ought to be a reasonable proxy for a company’s performance, at least over the long run.

The present study examines the return on investments in British Malaya channelled via the London Stock Exchange from 1889 to 1969. The territory we analyse includes the Straits Settlement, the Federated and Unfederated Malay States, and North Borneo. For the sake of simplicity, we will henceforth call this whole region ‘Malaya’, as a shorthand for the territories that composed the Federation of Malaya, later re-named Malaysia.

During the nineteenth century, London was the leading financial centre of the world, and most capital exports went through the London Stock Exchange. It was only by the early twentieth century that other financial centres, most importantly New York, challenged London’s primacy in the financial sector. Still, London remained one of the most important financial centres of the world throughout the period under examination in this article (Michie 2006; Cassis 2010). Furthermore, most of the capital invested in Malaya during the period under study originated in Britain (Latham 1978, 55–56; van Helten and Jones 1989, 163–64; Rasiah 1995, 50; Lindblad 1997, 64; Drabble 2000, 54; Twomey 2000, 139), while only a minor share came from other parts of the world, including, for example, Australia, USA, China and Japan (Leng 1974; Birch 1976; Lindblad 1998, 22;64; Hillman 2005; Yacob 2009; Latham 1978, 55–56; Jelenkovic et al. 2016, 163–64; Rasiah 1995, 50; Drabble 2000, 54; Twomey 2000, 139). Previous research has shown that the degree of international integration of financial markets for ventures that were operating internationally was high already in the nineteenth century (Campbell and Rogers 2017). If the capital invested in Malaya coming from other places than London targeted other (types of) ventures than that channelled via London, it could potentially have experienced a different return on investment than the one estimated in the present study. Whether that was the case may be topic for future research. Nevertheless, it seems plausible to assume that the return on investment that London investors faced when investing in Malaya would be a reasonable proxy for a weighted average of all investments in the colony.

In order to study the total return on investment, data on the price of the equity of companies operating in Malaya and data on dividends paid out to the shareholders in the same companies are required. Our measurement of risk—volatility—follows practice in financial history and it is derived from these data as the standard deviation of the annual return (Dimson et al. 2002, 54–55). Data on the price of shares can be found in publications such as the Investors’ Monthly Manual (IMM), a publication aimed at informing investors about what was happening on the London Stock Exchange since 1864, and The Times of London. Data from these sources have been digitized by the company Global Financial Data (GFD). For the purpose of this article, data on all companies registered as operating in Malaya or Singapore were acquired from GFD. In terms of reliability, previous research shows that GFD’s data are highly reliable when it comes to share prices. The frequency of the data is either daily or monthly (varying between companies and sometimes over time); we have here consistently used monthly data (i.e. for series where there are daily data, we have used data from the last trading day of each month). GFD’s database also contains data on other variables, but these show lower level of reliability, for example, due to missing data (see Rönnbäck and Broberg 2019, chap. 5). For the purpose of this article, data on these additional variables have therefore been assembled directly from a primary source, namely the London Stock Exchange Yearbooks, published annually since 1890 and providing key information on all the companies listed on the exchange, including data on the number of shares outstanding, gross dividends paid out to the shareholders, and any capital operations (such as splits).

Table 1 summarizes the number of companies in the sample and the number of observations (company-months) per sectoral portfolio as well as for the whole sample under study.

The category of “other” companies operates in various sectors, including real estate, commercial services, consumer products and plantations (other than rubber). The most important of these, in terms of market capitalization, were operating plantations (other than rubber) on Borneo. Both common and preferred stocks have been included in the sample. Preferred stock only make up a small fraction (seven data-series) of the sample, and at most constitute a few percentage points in terms of share of total market capitalization. The sample size varies over time, peaking in 1916 at 148 companies (see Appendix Fig. 5). An increase in the number of ventures meant that the concentration of the portfolio decreased over time. At the outset of the study, three companies—with the British North Borneo Company being the leading one—accounted for the whole sample in terms of market capitalization. By 1916, the three largest companies only accounted for ten per cent of the total market capitalization of the whole portfolio (see Appendix Fig. 6). In 1929–1930, there is a break in the series when the number of companies in the sample suddenly drops. This is largely attributable to a shift in the primary sources employed by Global Financial Data when constructing their database. Nonetheless, all major companies in terms of market capitalization remain in the sample, so the change is deemed to have comparatively limited effect upon market capitalization- weighted estimate of the total return on investment. Nominal return on investment have, finally, been calculated using data on historical inflation based on a consumer price index (O’Donoghue et al. 2004).

Malaysian stocks continued to be traded on the London Stock Exchange throughout the Japanese occupation of Malaya, from the end of 1941 to 1945. As the British boards and investors during this time would have had little influence over the company’s operations in occupied Malaya, trading would reflect anticipation of future earnings from the stocks.

4.1 Results

Figure 1 shows the market capitalization (in constant prices) of the 246 companies in our sample. During the nineteenth century, companies in ‘other’ sectors dominate the sample. This includes most notably the British North Borneo Company, chartered to colonize and administer North Borneo (Tregonning 1958; Griffiths 1974, chap. 16). There are, furthermore, a few tobacco and sugar estates as well as some other companies, several operating in North Borneo. After a long period of decline, companies operating in ‘other’ sectors saw their market capitalization increase at the end of the period under study, driven by a few companies involved in construction, real estate, and chemicals.

Our data confirm the boom-and-bust-pattern of the rubber sector put forth by previous scholars (see most importantly Drabble 1972; 1973). The pattern is clearly visible in Fig. 1, from the early booms in 1905–1910 to the slumps in in the interwar period and during the Japanese invasion.

Compared to rubber, tin mining experienced considerably less variation and strong secular growth. By the end of the period, the market capitalization of the mining companies was twice as big as the market capitalization of the rubber plantations.

Figure 2 shows an index of the total accumulated return on investment, by sector and for the whole sample of companies, over the period under examination. Averages by decade, again by sector and for the whole sample, are available in Table 2 (yearly data are reported in Appendix Table 4).

Source: see Fig. 1. Data on dividends paid out assembled from London Stock Exchange Yearbooks 1890–1970

Accumulated total return on investment in Malaya, by sector (index, 1888 = 100, logarithmic scale).

The return on investment in Malaya was high on average over the whole period under study. This was particularly the case in the tin mining sector, but also in the rubber plantations-sector. In order to understand this high return, we must look at the major changes over time.

One factor that has been suggested in previous research as driving a high return on investment in colonies was the presence of exploitative colonial institutions. In their article on the return on investment in the Netherlands Indies, Frans Buelens and Ewout Frankema interpret their findings of comparatively high return on investment as the effect of systematic labour repression in the colony (Buelens and Frankema 2015)Footnote 2, yet they do not test this hypothesis directly. Klas Rönnbäck and Oskar Broberg, in their study of the return on investments in colonial Africa, discuss whether what they call exploitative labour institutions might have affected the return on investments in the British colonies. They find some evidence tentatively supporting this interpretation in the form of a higher return on investments in settler colonies, generally described as being characterized by a higher degree of exploitative labour institutions, than in non-settler colonies (Rönnbäck and Broberg 2019, Fig. 13.5). Several scholars have noted that repressive or exploitative measures against labourers were in place also in British Malaya. Indentured servitude, for example, was continually in use in the early phase of this study, with “coolies” being imported from China or India legally until 1910, when the practice was abolished (Parmer 1960, 6–7; van Helten and Jones 1989, 171–74; Ramasamy 1992, 89–90; Lindblad 1998, 43). Colonial authorities were also active in repressing trade unions, and attempts by the labourers to collectively organize were still opposed in the 1940s (Ramasamy 1992). Previous literature in the field, however, tends to suggest that the measures grew less repressive over the period under examination, with unions, for example, starting to be officially recognized by the colonial authorities after the Second World War. If coercive labour institutions were the key explanatory factor driving the return on investments, the return then ought to have been at its highest during the early colonial period of Malayan history, when previous scholars agree that the colonial labour market institutions were the most repressive. This does not seem to have been the case. During the first decades for which data are available, the average investor in Malaya experienced quite substantial losses. Losses were the greatest in the mining sector. The claims made in the specialist literature on Malayan economic history that numerous of the early European tin mining ventures in Malaya failed economically thus find support in our analysis of the total return on investments (Fig. 2). British investments in the Malayan mining sector on average experienced astounding losses of 28.7 per cent per year in real terms in the 1890s, and 20.4 per cent per year in the 1900s (Table 2). At the outbreak of the First World War, the total return on investments index had dropped from 100 to 0.5. Investors in several other companies, including the British North Borneo Company, also experienced losses during this early period, but not as drastic as in the case of the mining sector (Table 2). As for investments in rubber plantations, these did certainly yield a very high return during the first years for which we have data (from 1906 onwards). This very high return does, however, in the main not seem to be attributable to the exploitative colonial institutions in general, but rather to the great international booms on the international rubber market in 1905–1906 and 1909–10, emphasized in much of the previous literature (Allen and Donnithorne 1957, 111–12; Lim 1969, 75; Stillson 1971; Drabble 1972; 1973, 30–34, 106–7). As rubber companies only start to appear in our sample in 1906, our data miss out the direct effect of the rubber boom in 1905. The following rubber boom in 1909–10 is, however, clearly visible in our data: the rubber portfolio of investments experienced an average real rate of return of 105 per cent per year during these two years. This boom was then followed by a stagnation that lasted several years. Although the losses that many Malayan companies faced might have been even greater in the absence of repressive labour institutions that kept labour costs low during the early years of colonialism in Malaya, the high average rate of return on investments that we find over the period under study cannot be attributed to such institutions per se, we believe.

The interwar years exhibit several important changes. Firstly, the portfolio of mining investments, which had hit its lowest point just before the outbreak of the war, gradually recovered. The sector’s performance was particularly strong in the first half of the 1920s and again in the second half of the 1930s, when the International Tin Cartel was in operation (Fig. 2). This finding supports the claim that European tin mining enterprises grew more competitive vis a vis Chinese entrepreneurs, who now lacked capital and labour to survive (Wong 1965, 203–30; Lim 1969, 50; Hennart 1986, 135–37; van Helten and Jones 1989, 165; Drabble 2000, 56). With an average real return on investments of 21.5 per cent per year in the 1920s, and 22.4 per cent per year in the 1930s, the mining portfolio had recovered from the losses experienced prior to the First World War. In contrast, investments in the rubber sector stagnated in terms of the return on investments. After the boom in 1909–10, the rubber sector fluctuated substantially. Our findings confirm that the performance of the rubber sector was very poor 1920–1921, and again during the Great Depression in the early 1930s (Fig. 2). Over the whole interwar period, investors in a rubber portfolio experienced a small loss (Table 2). Investments in other sectors than mining and rubber experienced a healthier return during the interwar period, particularly in the 1930s. However, by this time the market capitalization of these companies had been dwarfed by the vast amount of investments going into rubber and tin mining, as visible in Fig. 1.

As was noted above, Malayan stocks continued to be traded on the London Stock Exchange during the Japanese occupation of Malaya. The immediate occupation impacted British investors heavily. The “scorched earth” policy pursued by the British government, most certainly in combination with the uncertainty over whether the companies ever would be able to regain any Malayan assets, led to share prices dropping drastically for the vast majority of the Malayan ventures in our sample. As a consequence, investors faced major losses at the end of 1941 (with a return on investment of − 44.5 per cent this year for the whole Malayan portfolio), with tin mining being the most negatively impacted. As the war progressed, however, share prices of Malayan stocks started to recover, possibly reflecting regained investor confidence, thus leading to positive return on investment, particularly from 1943 onwards.

The post-war period brought about some further changes. Tin mining, on the one hand, continued its climb, experiencing a fabulous average return on investment, particularly in the 1950s with an estimated return on investment of 55.1 per cent per year. This extremely high average return on investment cannot be explained as risk premia. On the contrary, the tin mining companies were well established after 1914 and the volatility of return came down to levels that were relatively “normal” among colonial investments (Buelens and Frankema 2015; Buelens and Marysse 2009). One key factor to take into account was the process of decolonization of British Malaya. Previous research from Africa suggests that the process of decolonization occasionally could have severe negative effects upon the return on investments in that colony. Buelens and Marysse, for instance, have argued that the decolonization of Belgian Congo caused major losses for investors, reducing the average rate of return in the colony substantially (Buelens and Marysse 2009). Rönnbäck and Broberg have also suggested that this happened at least in the case of Egypt, with the effect of total return on investing in the country being negative as share prices fell. Decolonization was, however, not always associated with losses for foreign investors. In several African colonies, such as Nigeria or Ghana, the process of decolonization did not lead to any nationalization of foreign-held assets. The British investors hence lost little or no capital as a consequence of decolonization of these colonies (Rönnbäck and Broberg 2019, 329–30). As noted above, the process of decolonization of British Malaya was far from peaceful. It is thus possible that the armed insurgency which arose in 1948 could be an important factor in explaining the great losses experienced by several companies this very year, although our data would seem to suggest that investors in rubber companies actually were the ones experiencing losses (see Appendix Table 4), in contrast to previous research which has argued that the insurgency primarily impacted tin mining. From the perspective of the investors, the armed insurgency was essentially crushed during “the Emergency”, by the early 1950s, and the continued process of decolonization did not challenge the foreign investors’ ownership of assets in Malaya. As emphasized in previous research, the first independent government instead decided not to interfere with foreign ownership of assets (Lindblad 1998, 106–8; White 1994, 251; 2004, 2).

This non-intervention thus meant continued security for the companies’ ownership of assets in Malaya. The figures on the return on investment in late colonial and early post-colonial Malaya not only show no major losses on average during this period of decolonization, but they record extraordinarily high return on investment. While Nicholas White has stressed that British businesses operating in Malaya often expressed discontent with both the late colonial and early-independent political regimes (White 1994, 1997, 2000, 2004), this does not seem to have dissuaded them from holding on to, and profiting enormously from, their Malayan investments at this time. Besides the comparatively smooth process of decolonization, the high returns in this phase can be explained by looking at the three “pushes” that Chong-Yah Lim identified as important for the development of the modern Malayan economy (Lim 1969, 8–18). All these “three pushes” can be traced in our data. The years of the Korean War were particularly lucrative for the investors, as were the years of the first International Tin Agreement. The portfolio of investments in rubber ventures did also experience a very high return on investment during the post-war period, with the return on investments being particularly high in the 1950s (Table 2). Rubber ventures appear to have experienced similar patterns to that of tin-ventures, with very high total return in particular years—for example, during the Korean War—but generally at lower levels than tin. The year 1959 seems to have been especially profitable for the investors in both rubber and tin, with a total return on investment exceeding 100 per cent in both sectors, as shares prices boomed. It does not seem possible to isolate which specific factors would have driven the high return this particular year with any certainty, as the investors’ expectations in the first years of political independence (without nationalizations) no doubt interacted with other factors, such as the establishment of the International Tin Agreement. It is noteworthy that British investments in other sectors of the Malayan economy continued to have little impact upon the portfolio of companies in the sample, as it was the case in previous decades.

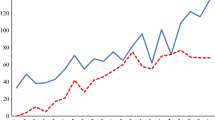

Over the whole period, colonial institutions and global and local political processes (e.g. the Japanese occupation, the “Emergency” and later decolonization) interacted with global market forces for the output from the Malayan mines and plantations. The price of the output remained one of the key factors influencing the return on investments over the long run. The correlation between the price of the output and the return on investment in a sector was, however, far from perfect, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

In both the cases of tin mining and rubber plantations, there seems to exist a relationship, albeit weak, between the price of the output (tin and rubber, respectively) on the international market, and the return on investments in companies involved in these sectors. The relationship is seemingly stronger in the case of tin, where both series exhibit a positive trend over time, and several of the years of particular peaks in the price also correspond to years of higher return on investment in tin mining companies. The market for rubber experienced a major boom between 1909 and 1910, which drove up the international price of rubber to extraordinarily high levels. This peak in the price of rubber is also associated with a very high return on investment, particularly in 1909. After a downfall in the 1920s, the price of rubber remained comparatively stable. The price movements that occurred did, however, to some extent also correlate with the return on investments in Malayan rubber production. In neither case is the correlation very strong, but this could be attributable to a time-lag, so that the return on investment might have responded to price changes over a slightly longer period of time.

Putting our estimates into internationally comparative perspective, the Malayan performance was very strong. Investments in Malaya exhibited a premium return of 2.7 percentage points per year above what investors could earn from investing elsewhere throughout the period under study, and 3.6 percentage points higher than what could be earned from investing in African colonies (Table 3). Compared to investments in the Netherlands Indies, the Malayan portfolio of (rubber) plantations ventures performed substantially better from the perspective of the investors over the whole period for which data are comparable (Table 3). The high return on investment can partly be explained in terms of the risk-return relationship. The average volatility of the total Malayan portfolio was 35.7 per cent for the entire period. This figure is higher than for a portfolio covering the same time and made up of colonial investments in Africa (Rönnbäck and Broberg 2019, 127), but lower than it has been reported for the Netherlands Indies (Buelens and Frankema 2015, 213). An important aspect of the relative high volatility of the Malayan portfolio was that it was so heavily dependent on tin and rubber. From an investor point of view, the high return was tempting, but the Malayan portfolio alone offered very limited opportunities for diversification.

5 Conclusion

A new wave of research on the return on investments across the globe has spurred in recent years. One of the aspects studied in this literature is whether the return on investments was higher in territories under colonization than it was elsewhere in world. Much of the previous research on this topic has focused primarily upon investments in Africa. In the present study, we have contributed with new data on the return on investments in an Asian colony: British Malaya. In this geographical context, we study the return on investments for a comparatively large sample of companies during the period from 1889 to 1969. We are thereby able to study not just the development over the colonial period, but also what happened to the return on British investments in Malaya during the early post-colonial period. Our results show that the return on investments in Malaya was extremely high, possibly the highest of all economies for which comparable data are available during the period under investigation. Our results would thus suggest that British Malaya was somewhat of a cash cow for investors at the London Stock Exchange, especially in the late colonial and early post-colonial period.

One factor emphasized in previous literature as an explanation of high return on investment in colonies is repressive colonial labour institutions. The theoretical argument being that by reducing labour costs, company profits could be increased. In British Malaya, coercive labour institutions were certainly imposed during the colonial period. However, as we have shown in this paper, the historical timing of when such institutions primarily were employed (during the early colonial period) does not match when the return on investments in Malaya was high (during the late colonial and early post-colonial period).

One factor of crucial importance for the return on investments in Malaya was the nature of the decolonization process. In some colonies, decolonization was highly contentious and it led to large-scale nationalizations of foreign-held assets. In such cases, the process of decolonization was often associated with major financial losses for foreign investors. The process of decolonization was certainly not peaceful in British Malaya either, with an armed insurgency taking place across the late 1940s and early 1950s. British investors might ex ante have feared the possible consequences of decolonization either if insurgence was to succeed, or if other radical forces took control over Malaya. However, the armed insurgency was repressed, and the regime that took power at independence abstained from any nationalizations of foreign-owned assets. The process of decolonization therefore did not lead to any great losses for the British investors in Malaya. Concurrent to decolonization, Malaya’s main outputs, tin and rubber, saw their demand skyrocket, as both of these commodities were of strategic interest for industrial and military purposes. This eventually played no small part in explaining why Malaya turned out to be such a valuable cash cow for the British investors.

Notes

Further restrictions were later imposed, for example, in order to keep Japanese investors out of the competition for land (Leng 1974).

They also add the caveat that the high return they estimate “may also partly reflect a higher risk-premium” without elaborating further on this topic.

References

Allen GC, Donnithorne AG (1957) Western enterprise in Indonesia and Malaya: a study in economic development. Longmans, London

Bach RL (1976) Historical patterns of capitalist penetration in Malaysia. J Contemp Asia 6(4):458–476

Bauer PT (1948) The rubber industry: a study in competition and monopoly. Longmans, Green and Co, London

Birch FD (1976) Tropical milestones: Australian gold and tin mining investments in Malaya and Thailand, 1880–1930. http://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/36467

Booth A (2008) The economic development of southeast Asia in the Colonial Era: C. 1870–1942. History Compass 6(1):25–53

Buelens F, Ewout F (2015) Colonial adventures in tropical agriculture: new estimates of returns to investment in the Netherlands Indies, 1919–1938. Cliometrica. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-015-0128-z

Buelens F, Marysse S (2009) Returns on investments during the colonial era: the case of the Belgian Congo. Econ Hist Rev 62(August):135–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00482.x

Campbell G, Rogers M (2017) Integration between the London and New York Stock exchanges, 1825–1925. Econ Hist Rev 70(4):1185–1218

Cassis Y (2010) Capitals of capital : the rise and fall of international financial centres, 1780–2009. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Chai H-C (1964) The development of British Malaya, 1896–1909. Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur

Christopher AJ (1985) Patterns of British overseas investment in land, 1885–1913. Trans Inst British Geogr, 452–466

Dimson E, Marsh P, Staunton M (2002) Triumph of the optimists: 101 years of global investment returns. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N. J.

Dimson E, Paul M, Mike S (2019) Credit suisse global investment returns yearbook 2019 summary. Credit Suisse, Zurich

Drabble J (1972) Investment in the rubber industry in Malaya c. 1900–1922. J Southeast Asian Stud 3(2):247–261

Drabble J (1973) Rubber in Malaya 1876–1922: the genesis of the industry. Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur

Drabble J (1974) Some thoughts on the economic development of Malaya under British administration. J Southeast Asian Stud 5(2):199–208

Drabble J (2000) An economic history of Malaysia, c 1800–1990: The Transition to Modern Economic Growth. Macmillan, Basingstoke

Edelstein M (1970) The rate of return to U.K. home and foreign investment, 1870–1913. Ph. d. Dissertation. University of Pennsylvania

Edelstein M (1976) Realized rates of return on UK home and overseas portfolio investment in the age of high imperialism. Explor Econ Hist 13(3):283–329

Edelstein M (1982) Overseas investment in the age of high imperialism: the United Kingdom, 1850–1914. Methuen, London

Gilbert CL (1977) The post-war tin agreements: an assessment. Resourc Policy 3(2):108–117

Gilbert CL (1996) International commodity agreements: an obituary notice. World Dev 24(1):1–19

Griffiths P (1974) A licence to trade: the history of English chartered companies. Benn, London

Grossman RS (2015) Bloody foreigners! Overseas equity on the London stock exchange, 1869–1929. Econ Hist Rev 68(2):471–521

Harvey C, Press J (1990) The city and international mining, 1870–1914. Bus History 32(3):98–119

Havinden MA, Meredith D (1996) Colonialism and development: Britain and its tropical colonies, 1850–1960. Routledge, London

Helten JJ, Geoffrey J (1989) British Business in Malaysia and Singapore since the 1870s. In: Davenport-Hines RPT, Geoffrey J (eds) British Business in Asia since 1860. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 157–88

Hennart J-F (1986) Internalization in practice: early foreign direct investments in Malaysian tin mining. J Int Bus Stud 17(2):131–143

Hillman J (1988) Malaya and the international tin cartel. Mod Asian Stud 22(2):237–261

Hillman J (1997) The impact of the international tin restriction schemes on the return to equity of tin mining companies, 1927–39. Bus Hist 39(3):65–80

Hillman J (2005) Australian capital and south-east Asian tin mining, 1906–40. Austral Econ Hist Rev 45(2):161–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8446.2005.00133.x

Hillman J (2010) The international tin cartel. Routledge, London

Huff WG (2002) Boom-or-bust commodities and industrialization in pre-World War II Malaya. J Econ Hist 62(4):1074–1115

Jelenkovic A, Sund R, Hur YM, Yokoyama Y, Hjelmborg JVB, Möller S, Silventoinen K (2016) Genetic and environmental influences on height from infancy to early adulthood: an individual-based pooled analysis of 45 twin cohorts. Sci Rep 6(1):1–13

John DW, Jackson JC (1973) The tobacco industry of north borneo: a distinctive form of plantation agriculture. J Southeast Asian Stud 4(1):88–106

Jomo KS (1986) A question of class: capital, the state, and uneven development in Malaya East Asian Social Science Monographs. Oxford University Press, Singapore

Jones E, Frost L, White C (1993) Coming full circle: an economic history of the pacific rim. Westview Press, Boulder

Khor KP (1983) The Malaysian economy: structures and dependence. Maricans, Kuala Lumpur

Latham AJH (1978) The international economy and the undeveloped world 1865–1914. Croom Helm, London

Lees LH (2007) International management in a free-standing company: the Penang Sugar Estates Ltd, and the Malayan Sugar industry, 1851–1914. Bus Hist Rev 81(1):27–57

Lees LH (2017) Planting empire, cultivating subjects: British Malaya, 1786–1941. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Leng YC (1974) Japanese rubber and iron investments in Malaya, 1900–1941. J Southeast Asian Stud 5(1):18–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022463400016830

Lim C-Y (1969) Economic development of modern Malaya. Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur

Lindblad JT (1997) Foreign investment in southeast Asia in historical perspective. Asian Econ J 11(1):61–80

Lindblad JT (1998) Foreign investment in Southeast Asia in the twentieth century. Macmillan, London

Matthews D (1990) Serendipity or economics? Tin and the theory of mineral discovery and development, 1800–1920. Bus Hist 32(3):15–48

Michie RC (2006) The global securities market a history. Oxford University Press, Oxford

O’Donoghue J, Louise G, Grahame A (2004) Consumer price inflation since 1750. Economic Trends No. 604.

Parmer JN (1960) Colonial labor policy and administration: a history of labor in the rubber plantation industry in Malaya, c 1910–1941. J.J. Augustin Inc., New York

Ramasamy P (1992) Labour control and labour resistance in the plantations of colonial Malaya. J Peasant Stud 19(3–4):87–105

Rasiah R (1995) Foreign capital and industrialization in Malaysia studies in the economies of east and South-East Asia. Macmillan, Basingstoke

Rönnbäck K, Broberg O (2018) All that glitters is not gold: the return on British investments in South Africa, 1869–1969. Stud Econ Econ 42(2):61–79

Rönnbäck K, Broberg O (2019) Capital and colonialism – the return on British investments in Africa 1869–1969. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Schmitz CJ (1979) World non-ferrous metal production and prices, 1700–1976. Cass, London

Smith GW, Schink GR (1976) The international tin agreement: a reassessment. Econ J 86(344):715–728

Stillson RT (1971) The financing of Malayan rubber, 1905–1923. Econ Hist Rev 24(4):589–598

Stone I (1999) The global export of capital from Great Britain, 1865–1914: a statistical survey. Macmillan, New York

Sutton A (2016) British imperialism and the political economy of Malayan independence. J Imperial Commonwealth Hist 44(3):470–491

Tajuddin A (2012) Malaysia in the world economy (1824–2011): capitalism, ethnic divisions, and “managed” democracy. Lexington Books, Lanham

Thoburn JT (1977) Primary commodity exports and economic development: theory, evidence and a study of Malaysia. Wiley, London

Tregonning KG (1958) Under chartered company rule (North Borneo 1881–1946). Malaya U.P, Singapore

Tuan WY (2010) More than a tea planter: john archibald russell and his businesses in Malaya, 1899–1933. J Mala Branch R Asiat Soc, 29–51

Twomey MJ (2000) A century of foreign investment in the third world. Routledge, London

White N (1994) Government and business divided: Malaya, 1945–57. J Imper Commonwealth History 22(2):251–274

White N (1997) The frustrations of development: British business and the late colonial state in Malaya, 1945–57. J Southeast Asian Stud 28(1):103–119

White N (1999) Gentlemanly capitalism and empire in the twentieth century: the forgotten case of Malaya, 1914–1965. In: Dumett R (ed) Gentlemanly capitalism and British imperialism: the new debate on empire. Longman, London, pp 175–195

White N (2000) The business and the politics of decolonization: the British experience in the twentieth century. Econ Hist Rev 53(3):544–564

White N (2004) British business in post-colonial Malaysia, 1957–70: neo-colonialism or disengagement? Routledge, London

White N (2015) The trouble with tin: governments and businesses in decolonizing Malaya. In: Ingulstad M, Perchard A, Storli E (eds) Tin and global capitalism: a history of the Devil’s Metal, 1850–2000. Routledge, London, pp 169–201

Wong LK (1965) The Malayan tin industry to 1914: with special reference to the states of Perak, Selangor, Negri. Sembilan and Pahang, Tucson

Yacob S (2009) Ford’s investment in colonial Malaya, 1926–1957. Bus Hist Rev 83(4):789–812. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000768050000091X

Yip YH (1969) The development of the tin mining industry of Malaya. University of Malaya Press, Kuala Lumpur

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Gothenburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 4 .

Sources: see Table 1

Sample size of Malayan sample of ventures, 1889–1969 (number of companies).

Sources: see Table 1

Three-firm concentration ratio of Malayan portfolio of investments, 1889–1969.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rönnbäck, K., Broberg, O. & Galli, S. A colonial cash cow: the return on investments in British Malaya, 1889–1969. Cliometrica 16, 149–173 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-021-00223-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-021-00223-8