Abstract

Purpose

The association between bariatric surgery outcome and depression remains controversial. Many patients with depression are not offered bariatric surgery due to concerns that they may have suboptimal outcomes. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between baseline World Health Organization-Five Wellbeing Index (WHO-5) and percentage total weight loss (%TWL) in patients after bariatric surgery.

Materials and Methods

All patients were routinely reviewed by the psychologist and screened with WHO-5. The consultation occurred 3.5 ± 1.6 months before bariatric surgery. Body weight was recorded before and 1 year after surgery. A total of 45 out of 71 (63.3%) patients with complete WHO-5 data were included in the study. Data analysis was carried out with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27) to determine the correlation between baseline WHO-5 and %TWL in patients having bariatric surgery.

Results

Overall, 11 males and 34 females were involved with mean age of 47.5 ± 11.5 and BMI of 46.2 ± 5.5 kg/m2. The %TWL between pre- and 1-year post-surgery was 30.0 ± 8.3% and the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index mean score was 56.5 ± 16.8. We found no correlation between %TWL and the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index (r = 0.032, p = 0.83).

Conclusion

There was no correlation between the baseline WHO-5 Wellbeing Index and %TWL 1-year post-bariatric surgery. Patients with low mood or depression need to be assessed and offered appropriate treatment but should not be excluded from bariatric surgery only based on their mood.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction/Purpose

Obesity is defined as a complex chronic disease characterized by excessive adipose tissue which causes a deterioration in health [1, 2]. There are numerous complications from obesity such as obstructive sleep apnea, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, osteoarthritis, reduction in fertility [3], and also cardiometabolic diseases and cancer which reduces life expectancy [4, 5]. However, the impact on mental health cannot be underestimated [6]. There is a bidirectional association between obesity and depression [7,8,9]. This means that the presence of one condition increases the risk of developing the other and vice versa. Evidence suggests shared biological mechanisms linking obesity and depression such as overlapping genetic bases [10], hyperactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [11, 12], and immuno-inflammatory activation which altogether alter the brain activity for mood and food [13].

Appropriate management of obesity needs to prevent the complications and improve physical and mental wellbeing. Such strategies may include medical nutrition, exercise, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery [14]. Bariatric surgery remains an effective treatment to treat obesity-related complications, maintain long-term weight loss, and improve quality of life [15, 16]. Evidence showed that bariatric surgery is associated with short-term [17] and long-term reduction of depressive symptoms up to 10 years post-operatively [18]. It is postulated that weight loss as a result of the surgery may lower the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines which may be partly responsible for the depression [19].

The association between depression and obesity [20,21,22] is across gender and racial groups [23]. However, it is controversial whether there is a relationship between depression and bariatric surgery outcomes [24]. Several studies showed that bariatric surgery is beneficial for depression [25,26,27,28]. However, there is also evidence that patients might worsen following surgery [26, 29, 30]. Pre-operative depression also does not appear to be associated with the outcome of surgery [31]. Many patients with depression are not offered bariatric surgery because of the concerns that they may have suboptimal outcomes [32]. The World Health Organization-Five Wellbeing Index (WHO-5), a questionnaire to screen for depression, is a useful screening tool to evaluate patient’s current mental wellbeing pre-surgery. It is a generic wellbeing scale without any diagnostic specificity but has been shown to be beneficial across many study fields [33]. More than half of patients with obesity may present with psychiatric illness such as depression [34]. Patients after bariatric surgery are also at an increased risk of suicide compared to the background population [35]. Thus, a multidisciplinary team approach which includes clinical psychologists and psychiatrists plays an important role in optimizing patient care. Our hypothesis was that there is no correlation between baseline WHO-5 and percentage total weight loss after 1 year. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the relationship between baseline World Health Organization-Five Wellbeing Index (WHO-5) and percentage weight loss in patients after bariatric surgery.

Materials and Methods

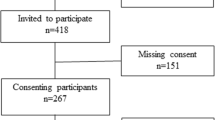

Approval for the evaluation of prospectively collected data was obtained from the hospital’s clinical audit and ethics committee (Clinical Audit Reference Number 3180). Patients who underwent bariatric surgery between 8 November 2018 to 10 August 2020 were included in the study. As part of the standard of care, patients were reviewed by the in-house psychologist and screened with WHO-5 before surgery. Body weight was recorded pre- and 1 year after surgery. The %TWL between pre- and 1-year post-intervention were calculated using Microsoft Excel. Data analysis was carried out with IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 27) to determine the correlation between %TWL and World Health Organization-Five Wellbeing Index (WHO-5) in patients having bariatric surgery. Both parameters were normally distributed and Pearson correlation was utilized to measure the linear association between the two variables.

The WHO-5 Wellbeing Index is a short questionnaire performed during patients’ pre-operative assessment with the clinical psychologist. Five statements require the respondents to rate their opinions on a scale of 0 to 5 (Table 1). To obtain the final score, the total raw score is then multiplied by 4. A total of 100 score defines the best respondents’ wellbeing and zero as the worst. A low score can be indicative of depression (≤ 50/100), with clinical depression indicated for scores of ≤ 28/100 [36].

Results

A summary of baseline characteristics of the patients for which the data was collected is represented in Table 2. Overall, 45 out of 71 patients (63.3%) who had bariatric surgery were found to have baseline WHO-5 recorded (n = 11 males, n = 34 females) despite the clinic protocol stating all patients should routinely have WHO-5 score pre-operatively as part of usual care. The mean age and BMI were 47.5 ± 11.5 years old and 46.2 ± 5.5 kg/m2 respectively. The WHO-5 questionnaire was conducted on average 3.5 ± 1.6 months prior to bariatric surgery.

The mean and SD pre-op weight was 133.6 ± 25.0 kg and the mean weight loss between pre and 1 year after the bariatric surgery was 40.1 ± 12.7 kg. The overall %TWL 1-year post-surgery was 30.0 ± 8.3%. The WHO-5 Wellbeing Index mean score was 56.5 ± 16.8. A total of 12 patients had WHO-5 wellbeing score < 50. Two patients had further psychiatric evaluation, another two were advised to continue psychotherapy, and five patients were asked to complete counselling prior to surgical approval. There were three out of 12 patients who did not require any additional mental health input, because they had sufficient support from their general practitioners or local mental health teams and thus were deemed suitable for surgery. Our investigation demonstrated that there was no significant correlation between %TWL and the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index (r = 0.032, p = 0.83) as shown in Fig. 1.

Conclusion

There was no correlation between the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index at baseline and the %TWL after bariatric surgery. The WHO-5 Wellbeing Index is one of the most widely used and reliable psychometric measurements worldwide [37]. Other depression screening tools for bariatric surgery candidates include the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) [38, 39]. The WHO-5 Wellbeing index was developed to assess mental wellbeing but can be employed as a screening tool for depression as it demonstrates a high sensitivity for this disorder. For example, using a cut-off score of ≤ 50 to screen for clinical depression, several studies revealed a sensitivity for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) depression ranging from 0.77 to 0.96 [40,41,42] and a specificity between 0.65 and 0.89 [40, 43, 44]. Furthermore, the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index is a short, non-invasive questionnaire which is applicable to various study fields such as endocrinology [45], cardiology [46], neurology [44], and psychology [47], and can be used across different age groups [48, 49]. Therefore, it is a useful screening tool in a bariatric clinic to examine patient’s current mental wellbeing pre-surgery.

Previous studies indicate a conflicting relationship between depression and bariatric surgery outcomes. For example, several studies suggested that patients with depression are unsuitable for surgery [32, 50, 51]. Bauchowitz et al. conducted a survey involving 188 bariatric surgery programs to examine psychological assessment practices for bariatric surgery candidates in the USA [32] and 95% of the programs considered current symptom of depression as a possible contraindication to surgery. Another study also found a negative relationship between depression and bariatric surgery outcomes [51]. Kalarchian et al. showed that patients diagnosed with Axis I clinical disorder, e.g., mood or anxiety disorders, using Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV were associated with poorer weight outcomes 6 months post-operatively compared to the subjects without Axis I clinical disorder. However, this study examined outcomes 6-month post-surgery and they did not report nadir weight which usually occurs later [15]. Other studies have suggested that patients with depression performed better after surgery [52,53,54]. In a survey conducted on patients after bariatric surgery (n = 1117), Odom et al. showed that higher BDI scores were correlated with a lower risk of weight regain 1-year post-surgery [54]. Another study showed that patients with pre-operative depression (measured by BDI) had more post-operation weight loss after 1 year [53]. However, a number of studies found no correlation between pre-operative depression versus weight loss in patients with bariatric surgery [31, 55, 56]. Powers et al. investigated 131 patients at 2 years and 5.7 years post-operatively with known psychiatric assessments prior to surgery [55]. They detected no relationship between presurgical psychiatric disorder and weight loss at follow-up. In a study by Fuchs and colleagues, the outcome of bariatric surgery (laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding) was examined in patients with pre-operative psychological evaluation (n = 590) [31]. The study observed that there was no difference in percentage excess weight loss (%EWL) and psychiatric disorders including depression at 1-year post-surgery (p = 0.76). In line with these studies, Semanscin-Doerr and colleagues also found no difference between the presence and absence of lifetime history of depression and %EWL [56]. Our result was in line with these studies.

The strength of our study was that the baseline WHO-5 Wellbeing Index was conducted by the same clinical psychologist, therefore, avoiding a potential bias that may occur in self-reporting method such as patients underreporting of symptoms [57]. The WHO-5 is an easy tool which can be readily adopted in any bariatric practice and to our knowledge, there is no published data examining the relationship between WHO-5 Index and %TWL in patients with bariatric surgery. The limitation of the current study includes a small sample size (n = 45) and only 1-year post-surgical follow-up, but the data is very clear suggesting a larger group size with longer follow-up may not provide different outcomes. In addition, the cohort of patients that we identified may have affected the data. Moreover, it was beyond the remit of this study to compare the outcomes of patients with low WHO-5 scores who received or did not receive psychological or psychiatric treatment because all those patients in our cohort were offered treatments as part of their multidisciplinary obesity care.

In conclusion, we found that there was no correlation between the baseline WHO-5 Wellbeing Index and %TWL 1-year post-bariatric surgery. Patients with low mood or depression need to be assessed and offered appropriate treatment but should not be excluded from bariatric surgery only based on their mood.

References

Bray GA. Medical consequences of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2583–9.

Collaboration NCDRF. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–42.

Kinlen D, Cody D, O’Shea D. Complications of obesity. QJM. 2018;111:437–43.

Grover SA, Kaouache M, Rempel P, et al. Years of life lost and healthy life-years lost from diabetes and cardiovascular disease in overweight and obese people: a modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:114–22.

Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1083–96.

Devlin MJ, Yanovski SZ, Wilson GT. Obesity: what mental health professionals need to know. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:854–66.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:220–9.

Mannan M, Mamun A, Doi S, et al. Is there a bi-directional relationship between depression and obesity among adult men and women? Systematic review and bias-adjusted meta analysis. Asian J Psychiatry. 2016;21:51–66.

Mannan M, Mamun A, Doi S, et al. Prospective Associations between Depression and Obesity for Adolescent Males and Females- A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157240.

Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Peyrot WJ, et al. Genetic Association of Major Depression With Atypical Features and Obesity-Related Immunometabolic Dysregulations. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74:1214–25.

Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychiatric disorders associated with Cushing’s syndrome. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:361–73.

van Rossum EF. Obesity and cortisol: New perspectives on an old theme. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25:500–1.

Milaneschi Y, Simmons WK, van Rossum EFC, et al. Depression and obesity: evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:18–33.

Ryan DH, Kahan S. Guideline Recommendations for Obesity Management. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:49–63.

Nguyen NT, Varela JE. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic disorders: state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:160–9.

Durrer Schutz D, Busetto L, Dicker D, et al. European Practical and Patient-Centred Guidelines for Adult Obesity Management in Primary Care. Obes Facts. 2019;12:40–66.

Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental Health Conditions Among Patients Seeking and Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315:150–63.

Gill H, Kang S, Lee Y, et al. The long-term effect of bariatric surgery on depression and anxiety. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:886–94.

Strawbridge R, Arnone D, Danese A, et al. Inflammation and clinical response to treatment in depression: A meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:1532–43.

Faith MS, Matz PE, Jorge MA. Obesity-depression associations in the population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:935–42.

Scott KM, McGee MA, Wells JE, et al. Obesity and mental disorders in the adult general population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:97–105.

Roberts RE, Deleger S, Strawbridge WJ, et al. Prospective association between obesity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:514–21.

Dong C, Sanchez LE, Price RA. Relationship of obesity to depression: a family-based study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:790–5.

Van den Eynde A, Mertens A, Vangoitsenhoven R, et al. Psychosocial Consequences of Bariatric Surgery: Two Sides of a Coin: a Scoping Review. Obes Surg. 2021;31(12):5409–17.

Switzer NJ, Debru E, Church N, et al. The Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Depression: a Review. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2016;10:12.

Peterhansel C, Petroff D, Klinitzke G, et al. Risk of completed suicide after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14:369–82.

Arhi CS, Dudley R, Moussa O, et al. The Complex Association Between Bariatric Surgery and Depression: a National Nested-Control Study. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1994–2001.

Loh HH, Francis B, Lim LL, et al. Improvement in mood symptoms after post-bariatric surgery among perople with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2021;37(8):e3458.

Courcoulas A. Who, Why, and How? Suicide and Harmful Behaviors After Bariatric Surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265:253–4.

Karlsson J, Taft C, Ryden A, et al. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: the SOS intervention study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:1248–61.

Fuchs HF, Laughter V, Harnsberger CR, et al. Patients with psychiatric comorbidity can safely undergo bariatric surgery with equivalent success. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:251–8.

Bauchowitz AU, Gonder-Frederick LA, et al. Psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates: a survey of present practices. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:825–32.

Topp CW, Ostergaard SD, Sondergaard S, et al. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84:167–76.

Sarwer DB, Polonsky HM. The Psychosocial Burden of Obesity. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016;45:677–88.

Castaneda D, Popov VB, Wander P, et al. Risk of Suicide and Self-harm Is Increased After Bariatric Surgery-a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;29:322–33.

Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Grafe K, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:131–40.

Primack BA. The WHO-5 Wellbeing Index performed the best in screening for depression in primary care. ACP J Club. 2003;139:48.

Cassin S, Sockalingam S, Hawa R, et al. Psychometric properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a depression screening tool for bariatric surgery candidates. Psychosomatics. 2013;54:352–8.

Hayes S, Stoeckel N, Napolitano MA, et al. Examination of the Beck Depression Inventory-II Factor Structure Among Bariatric Surgery Candidates. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1155–60.

de Azevedo-Marques JM, Zuardi AW. COOP/WONCA charts as a screen for mental disorders in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:359–65.

Liwowsky I, Kramer D, Mergl R, et al. Screening for depression in the older long-term unemployed. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:622–7.

Saipanish R, Lotrakul M, Sumrithe S. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the WHO-Five Well-Being Index in primary care patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:141–6.

Hammer EM, Hacker S, Hautzinger M, et al. Validity of the ALS-Depression-Inventory (ADI-12)–a new screening instrument for depressive disorders in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Affect Disord. 2008;109:213–9.

Schneider CB, Pilhatsch M, Rifati M, et al. Utility of the WHO-Five Well-being Index as a screening tool for depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:777–83.

Bech P, Gudex C, Johansen KS. The WHO (Ten) Well-Being Index: validation in diabetes. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65:183–90.

Birket-Smith M, Hansen BH, Hanash JA, et al. Mental disorders and general well-being in cardiology outpatients–6-year survival. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:5–10.

Krieger T, Zimmermann J, Huffziger S, et al. Measuring depression with a well-being index: further evidence for the validity of the WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5) as a measure of the severity of depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:240–4.

Heun R, Burkart M, Maier W, et al. Internal and external validity of the WHO Well-Being Scale in the elderly general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:171–8.

de Wit M, Pouwer F, Gemke RJ, et al. Validation of the WHO-5 Well-Being Index in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2003–6.

Herpertz S, Kielmann R, Wolf AM, et al. Do psychosocial variables predict weight loss or mental health after obesity surgery? A systematic review. Obes Res. 2004;12:1554–69.

Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al. Relationship of psychiatric disorders to 6-month outcomes after gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:544–9.

Burgmer R, Legenbauer T, Muller A, et al. Psychological outcome 4 years after restrictive bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1670–8.

Averbukh Y, Heshka S, El-Shoreya H, et al. Depression score predicts weight loss following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:833–6.

Odom J, Zalesin KC, Washington TL, et al. Behavioral predictors of weight regain after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010;20:349–56.

Powers PS, Rosemurgy A, Boyd F, et al. Outcome of gastric restriction procedures: weight, psychiatric diagnoses, and satisfaction. Obes Surg. 1997;7:471–7.

Semanscin-Doerr DA, Windover A, Ashton K, et al. Mood disorders in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy patients: does it affect early weight loss? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:191–6.

Hunt M, Auriemma J, Cashaw AC. Self-report bias and underreporting of depression on the BDI-II. J Pers Assess. 2003;80:26–30.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Roshaida Abdul Wahab collected the data and analyzed and wrote the manuscript. Heshma Al-Ruwaily, Therese Coleman, Helen Heneghan, Karl Neff, Carel W le Roux, and Finian Fallon collected the data, reviewed the manuscript, and contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

ClR reports grants from the Irish Research Council, Science Foundation Ireland, Anabio, and the Health Research Board. He serves on advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Herbalife, GI Dynamics, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi Aventis, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Glia, and Boehringer Ingelheim. ClR is a member of the Irish Society for Nutrition and Metabolism outside the area of work commented on here. He is the chief medical officer and director of the Medical Device Division of Keyron since January 2011. Both are unremunerated positions. ClR was a previous investor in Keyron, which develops endoscopically implantable medical devices intended to mimic the surgical procedures of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass. He continues to provide scientific advice to Keyron for no remuneration. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Points

• The association between bariatric surgery outcome and depression remains controversial.

• The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between percentage weight loss and World Health Organization-Five Wellbeing Index (WHO-5) in patients after bariatric surgery.

• There was no correlation between the baseline WHO-5 Wellbeing Index and percentage weight loss 1-year post-bariatric surgery.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdul Wahab, R., Al-Ruwaily, H., Coleman, T. et al. The Relationship Between Percentage Weight Loss and World Health Organization-Five Wellbeing Index (WHO-5) in Patients Having Bariatric Surgery. OBES SURG 32, 1667–1672 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06010-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-022-06010-2