Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is the most common bariatric surgical procedure worldwide. Educational videos of LSGs are available from online sources with YouTube® being the most popular online video repository. However, due to the unrestricted and uncontrolled nature of YouTube®, anyone can upload videos without peer review or standardization. The LAP-VEGaS guidelines were formed to guide the production of high-quality surgical videos. The aim of this study is to use the LAP-VEGaS guidelines to determine if videos of LSGs available on Youtube® are of an acceptable standard for surgical educational purposes.

Methods

A YouTube® search was performed using the term laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Appropriate videos were analysed by two individuals using the sixteen LAP-VEGaS guidelines.

Results

A total of 575 videos were found, of which 202 videos were included and analysed using the LAP-VEGaS guidelines. The median video guideline score was 6/16 with 89% of videos meeting less than half of all guidelines. There was no correlation between the LAP-VEGaS score and view count.

Conclusions

There is an abundance of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy educational videos available on YouTube®; however, when analysed using the LAP-VEGaS guidelines, the majority do not meet acceptable educational standards for surgical training purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is an established treatment for obesity and its complications. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is a first-line surgical procedure in the management of obesity. The first LSG case was described in 1999 as part of a duodenal switch. Following this, the LSG was used as a first-stage procedure for safer Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and subsequently was proven as an effective standalone procedure [1, 2].

The ability to effortlessly record procedures and YouTube’s® unregulated uploading policy has led to an abundance of surgical videos available to view, the standard of which is not policed. Indeed, fewer videos are going through the peer-review process prior to uploading [3, 4].

YouTube® is the most frequently used educational video source for medical students, surgical trainees, and surgeons, with up to 90% using it as a resource for surgical preparation. Despite its popularity and widespread use, a standard method of evaluating YouTube® medical videos has not yet been established [5,6,7].

The LAP-VEGaS (LAParoscopic surgery Video Educational GuidelineS) guidelines were created in 2018 to provide consensus lead advice on how to report a surgical video, in a bid to improve their quality for teaching purposes. The guidelines were formed by a panel of thirty-three international members from a range of surgical subspecialties. Thirty-seven consensus statements were formed, from which sixteen essential criteria were defined. The LAP-VEGaS guidelines have been validated independently as accurate in identifying overall high-quality videos and those suitable for acceptance for publication or presentation [8,9,10].

The formation of the guidelines stemmed from surgical trainees spending less time in the operating theatre and the need for supplementary, high-quality teaching methods to make up for the loss in operating time. With the current Coronavirus-2019 pandemic, numerous institutions, including within Australasia, North America, and the UK, have stopped non-critical elective surgical procedure. This will likely have an impact on surgical trainees’ exposure in the operating theatre, thereby adding further pressure to develop surgical skills via other means [11,12,13,14,15].

This study aims to assess the quality of educational YouTube® videos of sleeve gastrectomies as determined by their adherence to the essential LAP-VEGaS guidelines.

Method

A YouTube® search was performed on March 15, 2019 using the search term “laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy” in English, returning 575 videos. Videos were sorted by relevance, as this is the YouTube® default. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined below (Table 1). In total, 202 videos were included in the study, which were further analysed using the sixteen essential LAP-VEGaS guidelines (Table 2).

The sixteen essential criteria cover five domains. The first two criteria relate to the domain of video introduction, specifically identifying essential items such as the title, in which the procedure and pathology being treated are stated. Author information, such as names, institution(s), country, year of surgery and conflict of interest disclosures, should also be present. The case presentation comprises four criteria: operative imaging; baseline characteristics, including age, sex, American Society of Anaesthesiology score (ASA), body mass index (BMI), indication for surgery, prior surgeries and indication for surgery; relevant pre-operative workup and treatment. The demonstration of the procedure includes four criteria: position of the patient and theatre staff members, trocar position and variations, stage of the operation with constant reference to the anatomy and in a step-by-step fashion. Outcomes of the procedure should be addressed by means of operating time and time in hospital, photographs of wounds and the specimen and mention of morbidity and functional outcomes. Additional measures to improve the efficacy of the video as a learning resource cover the final two criteria and include the use of diagrams, photos, snapshots and tables to demonstrate anatomical landmarks and relevant or unexpected findings. Audio and/or written commentary in English language must be provided.

The main endpoint of this study was the number of LAP-VEGaS guidelines met for each video, which were assigned scores out of sixteen. For each of the included videos, the upload date, the number of views at the time of analysis, the length of the video and a URL were recorded.

Video analysis was undertaken separately by two of the authors, a surgical registrar and a senior medical student. Each reviewed 101 videos, noting any uncertainties and together forming a consensus.

A power calculation was carried out with 80% power and a moderate correlation (0.5) to achieve a sample size of twenty-nine. Assuming a low correlation of 0.2, a sample size of 193 was required.

The data were analysed using SAS 9.4 statistical software. Statistical significance was determined by Spearman’s correlation test between the LAP-VEGaS score and the number of views, length and date for each video. The Wilcoxon two-sample test was used to test for differences in the LAP-VEGaS scores between reinforcement groups. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 202 videos met the formulated inclusion criteria with a cumulative view count of 2,518,512 views and a mean of 12,511 views. Video length ranged from 0.75 to 84 min with a mean of 8.25 min. The earliest video included was uploaded on March 6, 2007.

According to the analysis, the number of videos uploaded per year showed an upwards trend over 2007–2019 (Fig. 1).

The LAP-VEGaS scores ranged from 2/16 to 15/16. The median was 6/16, and the interquartile range was 3. The LAP-VEGaS score showed a skewed distribution; therefore, median data values were reported.

There was no correlation between LAP-VEGaS score and number of views (rs = 0.09, p = 0.22), the length of the video (rs = 0.08, p = 0.23) or the date of video upload (rs = 0.02, p = 0.77).

Irrespective of the LAP-VEGaS score, we found an association between view count and video length (rs = 0.14, p = 0.04) and year of video (rs = − 0.36, p ≤ 0.01), with both newer and longer videos having a higher numbers of views.

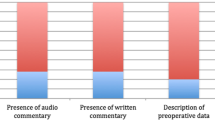

Overall, 11% (22/202) of videos met over half the criteria. Over 90% of the videos included the title (96.0%), patient anonymity (97.5%) and a step-by step approach (94.0%). Both the author’s information and anatomic demonstration were fulfilled in 82.7% and 89.1% of videos. Fifty per cent of all videos had written or spoken commentary. The other nine criteria were fulfilled in less than 38% of videos. Furthermore, imaging, workup, theatre time, morbidity and outcomes were fulfilled in less than 4% of videos. None of the videos provided disclosure statements. See Table 3.

The highest scoring video URL’s are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy videos found on YouTube® met the essential LAP-VEGaS guidelines for educational purposes. The results show that overall, videos are of poor to average quality when analysed using the sixteen LAP-VEGaS guidelines with 89% of videos meeting less than half of all guidelines. Reassuringly, some key guidelines were well represented, particularly the demonstration of anatomy and the information being displayed in a step-by-step process. There was no correlation between the number of LAP-VEGaS guidelines met and the view count, length of video or date of upload, similar to other studies [16, 17].

Other papers looking at educational quality of sleeve gastrectomy videos have shown similar results. Ferhatoglu et al. evaluated online sleeve gastrectomy videos with a range of assessment tools, such as the Sleeve Gastrectomy Specific tool (SGSS) and other generic assessment tools including Video Power Index (VPI), DISCERN Questionnaire and the Global Quality Score. Videos demonstrating surgical technique had a median SGSS of 5/24 and similarly poor results for the generic assessment tools. Furthermore, the most popular YouTube® videos had a negative correlation with scores across all tools, indicating other factors such as “attractivity” or presentation of the content, rather than educational quality, has a higher impact on viewer rates [16, 18].

Kaijser et al. used the Delphi consensus method to identify 23 key steps to the laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Similarly, van Rutte et al. identified 13 key steps as part of an Observational Clinical Human Reliability Assessment (OCHRA) study, identifying technical errors to guide key steps. Toolabi et al. reviewed 74 YouTube® videos and analysed them using ten of the key operative steps from Kaijser et al. All ten steps were met in 43% of videos. While these tools come with improved applicability to sleeve gastrectomy videos, they lose generalisability and with that, possibly widespread awareness and use [17, 19, 20].

The LAP-VEGaS guidelines were created to help standardise and validate surgical videos. Prior to the establishment of the LAP-VEGaS guidelines, there was no equivalent set of reporting guidelines for surgical video presentation leading to variable quality and reliability of content. The use of these guidelines prior to the publication of videos or peer review could enhance the overall quality of published educational surgical videos. However, it is not without compromise. While the LAP-VEGaS guidelines prescribe a standardised framework for structuring content of uploaded videos, they have no provision for assessment of the content’s technical quality. Furthermore, the guidelines have been designed to apply to all online laparoscopic videos, but some of the guidelines may not be relevant to certain procedures. In our study for example, pre-operative imaging would not be considered essential or routine for many bariatric surgeons performing LSG, potentially penalising videos in this study.

Many online videos focus on a specific aspect of a procedure, displaying the technical nuances or variations of established operations. Many of these videos may not meet educational standards when applying the LAP-VEGaS guidelines, as they forego many domains covered in LAP-VEGaS and focus instead on the procedural demonstration. Despite this, they remain popular amongst trained surgeons trying to learn new “tricks” to enhance their skills. We suggest LAP-VeGAS guidelines are equally important in these videos to ensure the indication and outcomes of said techniques are applicable and safe for use within the viewer’s practice. Equally, acknowledgement of common surgical technique variances may be an appropriate criterion in revisions of the LAP-VEGaS guidelines [21].

Another limitation of this study is that each video was analysed only once; each video analyst reviewed half of all videos with no secondary peer review, possibly resulting in variation between the video analyser’s reporting and scoring. The use of video analysers who were not trained bariatric surgeons may have affected the quality of the analysis. However, as the study involves assessing adherence to LAP-VEGaS guidelines rather than an analysis of surgical technique, we deemed the expertise level of the video analysers within this study appropriate. Another limitation is that YouTube® searching was performed using the default settings which can vary by geographical location. Finally, the search term may have been too narrow and excluded other relevant videos.

The posting of educational videos to platforms such as YouTube® is encouraging for the future of online learning but is not without cost. The open access nature of these platforms allows for distribution of unregulated and unstandardized methods which do not meet professional learning standards. There are other online video repositories, some of which are dedicated to surgical education. However, their quality has not consistently been shown to be superior to that found on YouTube®. An effective solution could involve surgical resident ‘consumers’ being educated in using this tool, that dedicated surgical education video sites use this tool, and uploading surgeons recommend only videos that are of high standard. An improvement in the quality of online videos could be achieved by creating and reviewing online videos with these guidelines [5, 22].

Conclusion

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy videos available on YouTube® that were analysed in this study did not demonstrate high quality when applying the LAP-VEGaS criteria. Medical professionals should be aware of this when using it as a learning resource to incorporate into their clinical practice.

References

Jossart GH, Anthone G. The history of sleeve gastrectomy. Bariatric Times. 2010;7(2):9–10.

Jaunoo S, Southall P. Bariatric surgery. Int J Surg. 2010;8(2):86–9.

Celentano V, Browning M, Hitchins C, et al. Training value of laparoscopic colorectal videos on the World Wide Web: a pilot study on the educational quality of laparoscopic right hemicolectomy videos. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(11):4496–504.

Rodriguez HA, Young MT, Jackson HT, et al. Viewer discretion advised: is YouTube a friend or foe in surgical education? Surg Endosc. 2018;32(4):1724–8.

Drozd B, Couvillon E, Suarez A. Medical YouTube videos and methods of evaluation: literature review. JMIR Med Educ. 2018;4(1):e3.

Rapp AK, Healy MG, Charlton ME, et al. YouTube is the most frequently used educational video source for surgical preparation. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):1072–6.

Celentano V, Smart N, Cahill RA, McGrath JS, Gupta S, Griffith JP, et al. Use of laparoscopic videos amongst surgical trainees in the United Kingdom. The Surgeon. 2019;17(6):334–9.

Celentano V, Smart N, Cahill RA, et al. Development and validation of a recommended checklist for assessment of surgical videos quality: the LAParoscopic surgery Video Educational GuidelineS (LAP-VEGaS) video assessment tool. Surgical Endoscopy. 2020:1–8.

Celentano V, Smart N, McGrath J, et al. LAP-VEGaS practice guidelines for reporting of educational videos in laparoscopic surgery: a joint trainers and trainees consensus statement. Ann Surg. 2018;268(6):920–6.

de’Angelis N, Gavriilidis P, Martínez-Pérez A, et al. Educational value of surgical videos on YouTube: quality assessment of laparoscopic appendectomy videos by senior surgeons vs. novice trainees. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14(1):22.

Iacobucci G. Covid-19: all non-urgent elective surgery is suspended for at least three months in England. BMJ. 2020;368:m1106. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1106.

Stahel, P.F. How to risk-stratify elective surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Patient Saf Surg. 2020;14:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-020-00235-9.

ANZGOSA. Guidelines for triaging upper GI and bariatric surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. [cited 2020 05/04/2020]. Available from: https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5162/guidelines-for-emergency-upper-gi-and-bariatric-surgery-during-the-covid-_v1_31-march-1.pdf.

CSSANZ. CSSANZ Recommendations during the COVID-19 Pandemic 2020 [05/04/2020]. Available from: https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5178/colorectal-surgical-society-of-australia-and-new-zealand-covid-19-statement.pdf.

Greensmith M, Cho J, Hargest R. Changes in surgical training opportunities in Britain and South Africa. Int J Surg. 2016;25:76–81.

Ferhatoglu MF, Kartal A, Ekici U, et al. Evaluation of the reliability, utility, and quality of the information in sleeve gastrectomy videos shared on open access video sharing platform YouTube. Obes Surg. 2019;29(5):1477–84.

Toolabi, K., Parsaei, R., Elyasinia, F. et al. Reliability and Educational Value of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy Surgery Videos on YouTube. OBES SURG. 2019;29:2806–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03907-3.

Desai T, Shariff A, Dhingra V, et al. Is content really king? An objective analysis of the public's response to medical videos on YouTube. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82469.

Kaijser MA, van Ramshorst GH, Emous M, et al. A Delphi consensus of the crucial steps in gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy procedures in the Netherlands. Obes Surg. 2018;28(9):2634–43.

van Rutte P, Nienhuijs S, Jakimowicz J, et al. Identification of technical errors and hazard zones in sleeve gastrectomy using OCHRA. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(2):561–6.

Schmidt RS, Shi LL, Sethna A. Use of streaming media (YouTube) as an educational tool for surgeons—a survey of AAFPRS members. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016;18(3):230–1.

Ferhatoglu, M.F., Kartal, A., Filiz, A.İ. et al. Comparison of New Era’s Education Platforms, YouTube® and WebSurg®, in Sleeve Gastrectomy. OBES SURG. 2019;29:3472–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-04008-x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent does not apply.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Study importance questions

What is already known on the subject

• Quality of online surgical educational videos is low.

• There is no established auditing process to assess quality prior to uploading or before publishing online videos.

• LAP-VEGaS is a novel quality assessment tool for online videos.

What are the new findings in your manuscript?

• Online laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy videos are of poor to average educational quality.

• LAP-VEGaS is a user-friendly tool used to quantify educational quality of uploaded videos and could be adopted across a range of online surgical videos.

How might your results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

• Uploading clinicians’ and video repository’s both have a role in auditing quality of uploaded videos.

• LAP-VEGaS could play an important part in raising the standard of educational surgical videos.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chapman, D., Weaver, A., Sheikh, L. et al. Evaluation of Online Videos of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy Using the LAP-VEGaS Guidelines. OBES SURG 31, 111–116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04876-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-04876-8