Abstract

Background

Since March 2003, we have used the Cousin Bioring in our laparoscopic gastroplasty procedures for morbid obesity. The Bioring belongs to the new generation of adjustable gastric bands. The aim of this study is to review our experience with this particular type of band.

Methods

Between March 2003 and March 2010, 316 patients had a laparoscopic implantation of the Cousin Bioring in our department. As many as 169 patients had the operation at least 5 years ago, of which 161 had a complete follow-up. Short- and long-term results were prospectively collected and analysed.

Results

There were no intra-operative and only two mild early post-operative complications. Mortality was zero. The mean percent of excess weight loss (%EWL) was 56% at 5 years, 55% at 6 years and 56% at 7 years. Of the 169 patients, four had a band removal for intolerance and/or insufficient weight loss and 11 (6.5%) developed late complications requiring surgery. We managed to solve all complications by minimally invasive procedures without loss of the device. Fifteen of the 169 patients suffered preoperatively from diabetes mellitus type 2. Ten of these had a remission after 5 years. The quality-of-life was assessed 3 years post-operatively for 164 patients and showed an improvement in 83.5% of them.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic implantation of the Cousin Bioring is a straightforward and safe operation. Complications occur, but they are rather benign and easy to remediate. The mean weight loss is considered successful (%EWL > 50) and persists 5 to 7 years after the operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding has been proven a safe and efficient surgical treatment of morbid obesity [1, 2]. The first laparoscopic implantations of gastric bands were carried out in Belgium in the early 1990s by Cadière [3] and Belachew [4] separately.

We were among the first centres both in Europe and worldwide to perform these procedures shortly after the market introduction of the first gastric bands in the fall of 1994. Thus, by March 2003, when we started the implantation of the Cousin Bioring, our department had implanted more than a thousand other gastric bands.

Description of the Adjustable Gastric Band Bioring

The Bioring is designed for laparoscopic implantation (Fig. 1). It has a streamlined profile without rigid protrusions and is made of supple silicon. It can be introduced into the abdomen either through a 12-mm trocar or through a 10-mm trocar stab wound. It glides without resistance through a tight retro gastric tunnel and appears to place itself in a ready position for closure since it is circularly pre-shaped. Arrows on the radio-opaque non-kinking catheter point to the end plug. Using two graspers and gentle traction, the band can be closed and opened ad libitum, both at the time of the original operation and during revisional surgery. Another feature is the very low pressure inside the band, which is maintained even at high fill volumes thanks to the “pair of bellows” inflation system. When the Bioring is being filled, the inflatable silicon does not stretch nor does it become thin. Instead, the inner silicon layer is pushed towards the middle of the ring (Fig. 2), which helps it maintain its natural adhesive characteristics, thus avoiding gastric wall slipping.

This figure shows a frontal section of the Cousin Bioring before and after partial inflation. Because of the “pair of bellows” mechanism, the inner layer of silicon is pushed towards the centre of the band. The inflatable silicon does not stretch, allowing for the pressure inside the band to remain very low, even at higher fill volumes

The Bioring is a grey monoblock band, apart from a green radio-opaque strip, which is stuck to the outside of the ring. These absorbent colours prevent a bothering flash effect during laparoscopy. The inflation area is 360°. When the band is inflated, even at high fill volumes, the pair of bellows system prevents the formation of sharp triangular creases at the level of the inflatable silicon. Instead, rounded-off folds are formed without contact either between the two inflatable edges or between inflatable and non-inflatable silicon (Fig. 3). This particular feature appears to prevent late central leaks by crease-fold fracture.

This figure shows the Bioring being inflated by 2 cm3 (left), 4 cm3 (middle) and 6 cm3 (right) of saline. The inflation area is 360°. The pair of bellows mechanism prevents the formation of sharp triangular creases at the level of the inflatable silicon. Instead, rounded-off folds are formed even at high fill volumes. This feature prevents the development of late central leaks by crease-fold fracture

The catheter of the Bioring is connected by a tapered connector to a 10.4-mm high low-profile access port with a large septum (diameter, 16 mm; Fig. 1). This new (since 2009) access port guarantees a stable position on the fascia and seems to facilitate puncturing during adjustments. Although the access port is radio-opaque, in our experience, radioscopy is rarely needed when adjusting the device. Since 2010, a self-adhesive access port of the same size is available.

The aim of this study is to review our experience with this particular type of adjustable gastric band. In this study, follow-up data of only the patients who had completed at least 5 years after the operation were analysed.

Materials and Methods

Between March 2003 and March 2010, 316 consecutive patients benefited from the laparoscopic implantation of a Cousin Bioring in our department. At the time of writing this paper, 169 patients had been operated on for 5 to 7 years with a mean of 69 months. In this group, the male-to-female ratio was 42/127. Body mass index (BMI) preoperatively ranged between 34 and 59 kg/m² (mean 42.6). Weights ranged between 88 and 190 kg (mean 117 kg) and ages between 16 and 66 years (mean 40 years). As many as 15 patients suffered from diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2). Seven patients were insulin-dependent, and eight were treated solely by oral anti-diabetic agents.

Of the 169 patients, 163 had a primary operation, two had a band implantation after a failed Mason procedure, one after a Nissen fundoplication and three had a rebanding procedure after removal of another type of band (twice for intra-gastric band erosions and once for leakage at the level of the inflatable part of the band). The rebanding procedures after band erosions were carried out 4 months after the band removal. In the case of leakage, band replacement was performed in one stage. All 169 patients were accessed via the pars flaccida route, and stabilising anterior gastric sutures were systematically placed.

In the first post-operative year, the patients were seen once a month on average. Later, the number of visits gradually decreased. If needed, we started adjustments of the band from the third post-operative week. We did not follow a strict adjustment algorithm but rather a custom-made adjustment policy, depending on the weight loss, the patients’ history (eating pattern, vomiting, etc.) and the individual wishes of the patients. Generally, the band was left empty at the time of its implantation. In most of the patients, at the time of the first adjustment, 2 to 3 cm3 of saline was injected; at the second, 1 to 1.5 cm3, followed by smaller increments. The mean number of visits and adjustments during the first five post-operative years are shown in Table 1.

The improvement of the quality-of-life (QOL) was assessed 3 years post-operatively in 164 patients using the Moorehead–Ardelt QOL questionnaire scoring test 1. This test evaluates self-esteem, physical, social, work and sexual well-being [5].

The evolution of one co-morbidity (DM2) was monitored by the use of anti-diabetic agents.

In this group of 169 patients, the follow-up was completed for 161 of them. We inquired by phone about the condition of the eight patients lost to follow-up. Five of them pretended to be satisfied by the treatment but refused further follow-up in our department because they had no problems, especially since three of them were also living abroad. None of them had a complication. One patient died of unrelated cause but had no problem with the band. One patient had the band explanted laparoscopically in another hospital for intolerance and insufficient weight loss, and another one had the band elsewhere explanted and converted to a laparoscopic gastric bypass for the same reasons.

For this study, short- and long-term data were prospectively collected, extracted and analysed from the paper charts of the patients, which are available for all patients and were managed exclusively by the corresponding author (EN).

Results

The Operation and the Post-Operative Course

All 169 procedures were completed laparoscopically. There were no intra-operative complications. Early post-operative complications were two cases of mild and transient dysphagia. Mortality was zero. Hospital discharge was on the first post-operative day for 165 of the 169 patients.

Weight Evolution

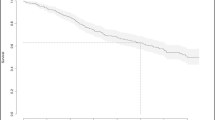

The mean weight loss of the 161 patients with a complete follow-up, expressed as absolute weight loss (kilograms), BMI loss and %EWL, is shown in Table 2. %EWL was calculated on weight above BMI 22.5 (ideal weight).

At 5 years, %EWL was <25 for six patients (3.7%), 25–50 for 21 patients (13%), 50–75 for 116 patients (72%), 75–100 for 15 patients (9.3%) and >100 for three patients (1.9%).

Late Complications Requiring Surgery and Reoperations

The reasons for and the number of re-interventions, as well as their surgical approaches, are listed in Table 3.

Of the 169 patients, four asked for band removal for intolerance and/or insufficient weight loss, two of them in our department and two in another hospital. One of the latter had a one-stage conversion to a gastric bypass. Another one of these four patients was the one who had a Nissen fundoplication earlier. While these are not real complications, they are an obvious failure of the treatment.

Four patients developed late pouch dilatations treated by laparoscopic repositioning of the Bioring to a higher level. These operations were completed uneventfully and with surprising ease. The helpful factors were the suppleness and streamlined profile of the band, as well as the ease of opening the Bioring.

One patient developed an anterior gastric wall slipping through the ring. At laparoscopy, the band was opened, the slipped stomach reduced underneath the band, some new gastro-gastric sutures were placed and the band was closed again.

The above-mentioned seven laparoscopic reoperations, carried out in our department, were uncomplicated, and all the patients were discharged on the first post-operative day.

Six patients needed a re-intervention for problems at or close to the access port. In one patient, there was a disconnection between the port and the catheter of the Bioring. In this patient, laparoscopy was needed to pick up the catheter from the abdomen. In two patients, there was a 180° rotation of an older type of port, which made the system inaccessible. Three more patients had a leak at the level of the catheter close to the access port. All these six problems were solved on a day-surgery basis. To date, we have no record of any infections of the device or any intra-gastric erosions or central leaks of the bands.

QOL

Three years after the operation, 4% of the 164 patients tested mentioned a diminished QOL; 12.5% experienced no change; 24% experienced improvement and 59.5% great improvement.

Evolution of Diabetes

Of the 15 DM2 patients, 10 benefited from a complete remission of DM2 (Table 4).

Discussion

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding procedure started more than 15 years ago and is today one of the highest performed surgical procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity worldwide [6]. It has meanwhile been proven an efficient and safe method.

In the beginning, as with any new procedure, there were numerous problems and complications [1, 2, 7–11]. This was due to several reasons. First, there was the learning curve and the lack of appropriate surgical instruments. Second, in the 1990s, the bands were implanted via the perigastric route, which caused a significant number of anterior and posterior gastric wall slippings, as well as some band erosions [1, 2, 10, 12–14]. In a retrospective study of 973 patients who had a Lap-Band implanted (511 first patients perigastric and 462 last patients pars flaccida), Dargent reported a decrease in the number of slippings within 34 months after the operation from 5.2% (perigastric) to 0.6% (pars flaccida) [10]. In a randomised prospective study of 202 patients who had a Lap-Band implanted (101 patients perigastric and 101 patients pars flaccida), O’Brien reported a 16% prolapse rate after 2 years in the perigastric group compared to 4% in the pars flaccida group [12]. Third and last, the first-generation bands were hard and rigid high-pressure bands with prominent protrusions; they were difficult or impossible to reopen, with poor connections between the access port and the catheter and fragile silicon at the level of the inflatable part. With growing experience, adapted surgical instruments and better optical systems, the ubiquitous use of the pars flaccida route with somewhat higher placement of the bands and the availability of a new generation of smooth and supple low pressure bands, overall results have improved remarkably [1, 2, 10, 12, 13]. At the time of our first Bioring implantations in 2003, all the above-mentioned requirements were met. Consequently, we succeeded to operate 169 consecutive patients without intra-operative and with only two benign early post-operative complications.

However, some late complications developed. In this series of 169 patients with a follow-up of at least 5 years and a mean follow-up of 69 months, there were six (3.6%) complications requiring laparoscopic reoperations (four pouch dilatations, one gastric wall slipping and one port disconnection) and five (3%) port-related complications which we managed to treat by a strictly subcutaneous approach. Until today, there were no erosions, central leaks or infections of the Bioring. So far, all these late problems were swiftly treated without complications and without the loss of the device. In addition, four of the total group of 169 patients (2.4%) had a band removal for intolerance and/or insufficient weight loss, one of them with conversion to a gastric bypass. Thus, the overall complication rate was 11 (6.5%), and the reoperation rate was 15 in 169 patients (8.9%).

Review of the literature indicates that this late complication and reoperation rate were low. Weiner reported similar results in a study of 984 patients (most of them Lap-Bands). Major complications including slippings, erosions and band replacements occurred in 3.9%, and port problems occurred in 2.2% of the patients. However, the follow-up period in this series was somewhat shorter (follow-up 1–99 months; mean 55.5 months) compared to our series, and 24 patients had a non-complete follow-up [1].

In a series of 1,000 patients (1,111 patients of whom 111 lost to follow-up) who had a Lap-Band implanted, Chevallier reported a cumulative rate of complications of 19.3%. Abdominal reoperations, including port disconnections, were required in 11.1% of the patients. In addition, 3.6% of the patients had a port problem that was treated by a subcutaneous approach. However, the follow-up period in this series ranged only between 0 and 7 years (5 and 7 years in our series) and 11% of the patients were lost to follow-up [13]. In a series of 1,791 patients, after Lap-Band implantation, Favretti reported a 5.9% major complication rate (including slippings, erosions, pouch dilatations, band removals for intolerance and infections) and 11.2% port-related problems. The follow-up in this series ranged between 0 and 12 years and about 9% of the patients were lost to follow-up [15]. In a series of 591 patients after implantation of a Lap-Band, a Lowate band, a Swedish band or a Minimizer band, Biagini reported a late complication rate of 22.3%. Of these complications, 35.5% were band failures, half of them at the level of the port and half of them at the level of the catheter or the inflatable part of the device (leaks or failures of the locking mechanism). Other complications were slippings, erosions, infections, intolerances and high band positions. The follow-up in this study ranged between 0 and 10 years (mean 35 months), and many patients were lost to follow-up (e.g. in the group of patients >4 years after the initial operation, 25.5% were lost to follow-up) [2].

In a study of 123 patients after implantation of a Swedish band, Tolonen reported a complication rate of 24.4%, including leaks, slippings, erosions, infections and severe reflux symptoms. As many as 30 patients (24.4%) needed at least one reoperation, 10 of them for a central leak of the band but only three (2.4%) of them for a problem at the level of the port. The follow-up period in this study ranged between 5 and 11 years (mean 86 months) but 20% of the patients were lost to follow-up at 5 years and 30% at 8 years [14]. Recently, Mittermair reported in a study of 785 patients who had a Swedish band implanted complications (but apart from the classic complications also including oesophagitis and oesophageal dilatations) in 50.4% of the patients. Fifty patients (6.4%) developed a central leak of the band. A reoperation was needed in 32% of the patients. Reoperation rate at the level of the port was 9.17%. The follow-up period in this study ranged between 1 and 10 years (mean 3 years). Many patients in this study were lost to follow-up (completeness of follow-up 73%) [8].

In a study of 317 patients treated with either a Lap-Band or a Swedish band, Suter reported 33.1% of the patients with at least one late complication (but apart from the classic complications also including intolerance, severe reflux symptoms and insufficient weight loss). As many as 133 reoperations were needed in 94 (29.6%) patients, of which 45 were needed at the level of the port. The follow-up period in this study ranged between 27 and 101 months (mean 74 months), and depending on the number of years after the initial operation, 1.3% to 33.4% of the patients were lost to follow-up (e.g. 11.8% of the eligible patients 5 years after the initial operation) [7].

In this study, the mean weight loss curve expressed as %EWL calculated on weight above BMI 22.5, went up steeply during the first year (%EWL 46) and reached its summit after 3 years (%EWL 58) then went slightly down over 2 years (%EWL 56 after 5 years) and then stabilised. Reported weight losses after gastric banding vary greatly in recent literature. Favretti reported a mean EWL of only 37.3% and 37.4% 5 and 6 years, respectively, after Lap-Band implantation [15] whereas Biagini reported mean EWL of 82.8% 6 years after implantation of several types of gastric bands [2]. In a systematic review of the literature, O’Brien reported a mean EWL of 54% and 53% 5 and 6 years after implantation of Lap-Bands and Swedish bands [16]. Most other authors reported similar EWL between 45% and 60% after 5 or 6 years [1, 8, 14], and this was our experience too. We believe that the major weight loss achieved over the first year was influenced by our adjustment policy. Especially during the first post-operative months, we performed frequent and rather aggressive adjustments. Subsequently, adjustments were more gentle which helped achieve fine-tuning of the fill volume at the end of the weight-loss process. Even several years after the operation, we regularly perform adjustments in order to obtain a permanent weight loss, also taking into account the wishes of each individual patient (Table 1). We also believe this policy has contributed to the fact that only four of the 169 patients have asked for a band removal for intolerance and/or insufficient weight loss. As a consequence, it is not surprising that we have found that 83.5% of patients experienced a better or a markedly better QOL 3 years after the operation compared to preoperatively. Myers reported similar results in a study of 67 patients with a mean follow-up of 27 months, but by using the Moorehead–Ardelt QOL questionnaire scoring test 2 [17]. Of the 169 patients, 15 suffered preoperatively from DM2, seven of them being insulin-dependent. Of these seven patients, four benefitted from a full remission of DM2 after 5 years, one needed oral anti-diabetic agents only and two remained insulin-dependent. Of the eight DM2 patients treated preoperatively by anti-diabetic agents solely, six benefitted from a full remission after 5 years while two continued their medication (Table 4). O’Brien recently reported similar results where gastric banding leads, in adults with mild to severe obesity, to remission in three out of four patients [18].

In conclusion, the results of this study appear to show that laparoscopic implantation of the Cousin Bioring for morbid obesity is a very safe operation. The number of late complications requiring surgery so far has been low (6.5%) compared to most other recently published series. We believe this is partly because we had already an extensive experience with other gastric bands when we started implantations of Bioring and partly because of the specific characteristics of the Bioring itself. Moreover, all complications could be solved through minimally invasive and safe procedures and without the loss of the implant. The mean weight loss in this study is comparable to what has been reported in recent literature and can be considered as acceptable (%EWL > 55) up to 5, 6 and 7 years after the operation. After 5 years, 134 patients (83.2%) had an acceptable %EWL > 50. Not all the patients with a %EWL < 50 after 5 years were disappointed. In the vast majority of the patients, maximal patient satisfaction was achieved thanks to the adjustability of the system, allowing for an individual compromise between good weight loss and acceptable food restriction.

References

Weiner R, Blanco-Engert R, Weiner S, et al. Outcome After Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding - 8 years Experience. Obes Surg. 2003;13:427–34.

Biagini J, Karam L. Ten Years Experience with Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding. Obes Surg. 2008;18:573–7.

Cadière GB, Bruyns J, Himpens J, et al. Laparoscopic Gastroplasty for Morbid Obesity. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1524–5.

Belachew M, Legrand MJ, Defechereux TH, et al. Laparoscopic Adjustable Silicone Gastric Banding in the Treatment of Morbid Obesity. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:1354–6.

Oria H, Moorehead M. Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System (BAROS). Obes Surg. 1998;8:487–99.

Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic / Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2008. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1605–11.

Suter M, Calmes JM, Paroz A, et al. A 10-year Experience with Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding for Morbid Obesity: High Long- Term Complication and Failure Rates. Obes Surg. 2006;16:829–35.

Mittermair RP, Obermüller S, Perathoner A, et al. Results and Complications after Swedish Adjustable Gastric Banding- 10 Years Experience. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1636–41.

Niville E, Dams A, Vlasselaers J. Lap-Band Erosion: Incidence and Treatment. Obes Surg. 2001;11:744–7.

Dargent J. Pouch Dilatation and Slippage ater Adjustable Gastric Banding: is it Still An Issue? Obes Surg. 2003;13:111–5.

Niville E, Dams A. Late Pouch Dilations After Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric And Esophagogastric Banding: Incidence, Treatment and Outcome. Obes Surg. 1999;9:381–4.

O’Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C, et al. A Prospective Randomized Trial of Placement of The Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band: Comparison of The Perigastric and Pars Flaccida Pathways. Obes Surg. 2005;15:820–6.

Chevallier J, Zinzindohoué F, Douard R, et al. Complications after Adjustable Gastric Banding for Morbid Obesity: Experience With 1000 Patients Over 7 Years. Obes Surg. 2004;14:407–14.

Tolonen P, Victorzon M, Mäkelä J. 11-year Experience with Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding for Morbid Obesity - what Happened to the First 123 Patients? Obes Surg. 2008;18:251–5.

Favretti F, Segato G, Ashton D, et al. Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding in 1791 Consecutive Obese Patients: 12-Year Results. Obes Surg. 2007;17:168–75.

O’Brien PE, McPhail T, Chaston TB, et al. Systematic review of Medium-term Weight Loss After Bariatric Operations. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1032–40.

Myers J, Clifford J, Sarker S, et al. Quality Of Life After Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding Using the Baros and Moorehead-Ardelt Quality Of Life Questionnaire II. JSLS. 2006;10(4):414–20.

O’Brien PE. Bariatric surgery: Mechanisms, Indications and Outcomes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1358–65.

Disclosure

Erik Niville is a consultant with Cousin Biotech. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Niville, E., Dams, A., Reremoser, S. et al. A Mid-term Experience with the Cousin Bioring—Adjustable Gastric Band. OBES SURG 22, 152–157 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-011-0427-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-011-0427-9