Abstract

Background

The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry (DSR) was established in 2004. The purpose of the registry is to monitor and improve the outcome of shoulder arthroplasty surgery in Denmark.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to describe the organization of the DSR and review published DSR papers with a special focus on patients with osteoarthritis.

Methods

All Danish public and private hospitals report to the DSR. Since 2006, when reporting became mandatory, the completeness of reporting has been over 90% each year. Surgeons report patient and operative data electronically at the time of the operation. The Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index at 1 year is used as patient-reported outcome. A revision is defined as removal or exchange of any component or the addition of a glenoid component. The revision is linked to the primary procedure with use of a unique civil registration number, which is given to all Danish citizens at birth.

Results

The registry has published five papers focusing on patients with osteoarthritis. The WOOS score was significantly higher after anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty. The WOOS score after resurfacing hemiarthroplasty varied and was often disappointing especially in young patients. The WOOS score after revision arthroplasty for failed resurfacing hemiarthroplasty was low and disappointing. The short- and mid-term survival rates of anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty were high for both the stemmed and the stemless humeral components.

Conclusion

The DSR has recorded significant changes in Danish surgeons’ approach to patients with osteoarthritis. Today, anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty with either a stemmed or a stemless humeral component is preferred in most cases.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Das dänische Schulterendoprothesenregister (DSR) wurde 2004 initiiert. Die Intention war, die Ergebnisse nach Schulterendoprothesenimplantationen in Dänemark zu beobachten und zu verbessern.

Fragestellung

Ziel der vorliegenden Arbeit war es, den Aufbau des DSR vorzustellen und die bisher aus dem DSR veröffentlichten Artikel mit speziellem Fokus auf Omarthrosepatienten zusammenzufassen.

Methoden

Alle öffentlichen und privaten dänischen Krankenhäuser dokumentieren im DSR. Seit 2006, als die Dokumentation verpflichtend wurde, liegt die Vollständigkeit der Berichterstattung jährlich bei über 90 %. Zum Zeitpunkt der Operation werden die Daten der Patienten und zur Operation elektronisch von den Chirurgen dokumentiert. Der Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) Index ein Jahr postoperativ wird als Ergebnis nach Angabe des Patienten („patient-reported outcome“) genutzt. Eine Revision ist als Wechsel oder Entfernung jeglicher Prothesenkomponenten oder nachträgliche Implantation einer Glenoidkomponente definiert. Die Revision kann mithilfe einer individuellen Bürgerregistrierungsnummer, die jedem dänischen Bürger bei Geburt zugewiesen wird, mit der Primärprozedur verknüpft werden.

Ergebnisse

Das Register hat 5 Artikel mit Fokus auf die Omarthrose publiziert. Der WOOS-Score war nach anatomischer Schultertotalendoprothese verglichen mit der Hemiendoprothese signifikant höher. Der WOOS-Score nach Oberflächenersatz-Hemiendoprothese war inkonstant und v. a. bei jüngeren Patienten oft enttäuschend. Der WOOS-Score nach Revisionsarthroplastik bei Versagen der Oberflächenersatz-Hemiendoprothese war inkonstant und enttäuschend. Die kurz- und mittelfristigen Überlebensraten der anatomischen Schultertotalendoprothese sind sowohl für die schaftfreie Prothese als auch für die Schaftprothese hoch.

Schlussfolgerungen

Im DSR zeigen sich signifikante Änderungen der Behandlung von Patienten mit Omarthrose durch dänische Chirurgen. Aktuell wird die Totalendoprothese mit oder ohne Schaft in den meisten Fällen bevorzugt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry (DSR) was initiated in 2004 by a group of Danish shoulder surgeons. The purpose was to monitor and improve the outcome of shoulder arthroplasty surgery in Denmark [11]. The registry is financed by the government and does not depend on commercial parties. It has published papers describing the nationwide results of shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis.

The objective of the present study was to describe the organization of the DSR and review DSR publications with a special focus on patients with osteoarthritis. Our hypothesis was that systematic interpretation of registry data can lead to improved patient-reported outcomes and limit the need for implant revision.

Method

The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry

The DSR was initiated by a group of Danish surgeons with support from the Danish Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. The registry is owned and financed by the five Danish counties. It is an independent registry but has the same administration as the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Registry, the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Registry, and the Danish Registry for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. The annual budget of the four registries is approximately € 500,000. The steering committee consists of shoulder surgeons representing each region in the country, a statistician, an epidemiologist, and a shoulder surgeon representing the Danish Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. The steering committee is responsible for defining the strategies and supervising the annual report.

The coverage, defined as the proportion of hospitals reporting to the registry, is 100% because reporting is mandatory for all Danish public and private hospitals. The completeness of reporting is defined as the number of arthroplasties reported to the registry compared with the number of arthroplasties reported to the National Patient Register—an administrative database used by the Danish health-care authorities to reimburse expenses of any hospital treatment including shoulder arthroplasty. Since 2007, the completeness of reporting has been well above 90%.

Surgeons report all data electronically at the time of the operation

Surgeons report patient and operative data electronically at the time of the operation. The reporting form and the dataset were revised in 2016. The old and the new dataset are scientifically compatible.

Patient-reported outcome

The Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index at 1 year is used as patient-reported outcome. The WOOS is a disease-specific questionnaire that measures the quality of life for patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis. There are 19 questions that are answered on a visual analog scale ranging from 0 to 100. Thus, the total score ranges from 0 to 1900, with 1900 being the worst. For simplicity of presentation, the total score is converted to a percentage of the maximum score, with 100 being the best [6]. The Danish version of the WOOS has been translated and cross-culturally adapted and validated with the use of classic test theory [12]. The WOOS questionnaire is sent to patients by mail and their answers are handled by the registry without involving the surgeons. In the case of revision, death, or emigration within the first year, the 1‑year WOOS score cannot be obtained. The questionnaire is only sent to the patients once, without any preoperative assessment or long-term follow-up.

Arthroplasty survival rate

A revision is defined as removal or exchange of any component or the addition of a glenoid component. The revision is linked to the primary procedure via of a unique civil registration number that is given to all Danish citizens at birth. The civil registration number is also used when information about patients who die or emigrate is obtained from the National Registry of Persons. Each patient is included in the cumulative survival analysis from the date of the primary procedure until revision, death, emigration, or end of follow-up.

The revision is reported by the surgeon at the time of the procedure and includes the same variables as the primary procedure but with additional information about the date of revision, new arthroplasty type, and reason for revision. Until 31 December 2015 it was possible to report more than one reason for revision. If more than one reason for revision is reported, the following hierarchy is used so that only one reason is registered: periprosthetic joint infection, periprosthetic fracture, luxation and instability, loosening, rotator cuff problem, and other reasons including glenoid wear.

The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association

Since 2014, the DSR has collaborated with the national shoulder arthroplasty registries in Finland, Norway, and Sweden in the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA). A common dataset has been defined based on variables that all four registries can deliver and where consensus regarding definitions and categories has been reached. Revision—defined as removal or exchange of any component or the addition of a glenoid component—is used as outcome. Currently, there is no patient-reported outcome in the dataset, but the WOOS index at 1 year is expected to be included from 2020. The process of merging data and the dataset were described in detail by Rasmussen et al. in 2016[9].

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to illustrate the unadjusted cumulative survival rates and the log–rank test was used for comparison. The univariate and multivariate cox regression model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A linear regression model was employed to report the WOOS score when subgroups were compared.

Results

Patient-reported outcome

We assessed the outcome of 1209 arthroplasties for osteoarthritis reported to the DSR from 2006 to 2010. The mean WOOS score at 1 year was 78 for anatomical total shoulder arthroplasties and 66 for hemiarthroplasties. In a multiple linear regression model, the difference of 10 (95% CI: 5–15) was statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that total shoulder arthroplasty should be preferred for osteoarthritis [15].

The patient-reported outcome of 873 resurfacing hemiarthroplasties for osteoarthritis reported to the DSR from 2006 to 2010 was published in 2014. The mean WOOS score was 67 (range: 0–100). Of these patients, 165 were 55 years or younger. Their mean WOOS score was 55, which was significantly lower than for older patients. The authors concluded that the outcome of resurfacing hemiarthroplasty in younger patients was worrying [16].

The outcome of resurfacing hemiarthroplasty in younger patients was worrying

The outcome of 1210 resurfacing hemiarthroplasties for osteoarthritis reported to the DSR from 2006 to 2012 showed that the mean WOOS score was 69 and 25% of the patients had a WOOS score below 50. Of these patients, 241 were 55 years or younger. Their mean WOOS score was 55, and 46% had a WOOS score below 50. Thus, the results could not support the continued use of resurfacing hemiarthroplasty [14].

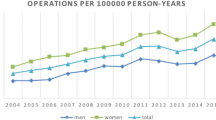

The DSR has observed significant changes in Danish surgeons’ approach to patients with osteoarthritis. The proportion of anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty increased from 3% and 7% in 2006 to 53% and 27% in 2015, respectively. The proportion of resurfacing hemiarthroplasty decreased from 77% to 3%. In that period, the mean WOOS score for patients with osteoarthritis increased from 62 to 79.

Arthroplasty survival rates

We assessed the outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis using data from the NARA dataset. There were 1587 stemmed hemiarthroplasties, 1923 resurfacing hemiarthroplasties, and 2340 anatomical total shoulder arthroplasties. The mean follow-up time observed was 4.3 years for stemmed hemiarthroplasty, 4.3 years for resurfacing hemiarthroplasty, and 3.1 years for total shoulder arthroplasty. The 10-year cumulative survival rates were 0.93, 0.85, and 0.96, respectively. In the multivariate Cox regression model, the HR for revision of stemmed hemiarthroplasty and resurfacing hemiarthroplasty was 1.4 (95% CI: 1.0–2, p = 0.04) and 2.5 (95% CI: 1.9–3.4, p < 0.001), respectively, with total shoulder arthroplasty as the reference. The lowest arthroplasty survival rate was found for patients who were treated with resurfacing hemiarthroplasty and who were younger than 55 years (n = 354). Their 10-year cumulative arthroplasty survival rate was 0.75. The authors concluded that the results support the use of anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty for all ages [10].

If resurfacing hemiarthroplasty is used, revision cannot be relied on as a fallback

Recently, we compared the 6‑year cumulative survival rate of 761 stemless total shoulder arthroplasties and 4398 stemmed total shoulder arthroplasties using data from the NARA dataset. The survival rates were 0.95 and 0.96, respectively (p = 0.77). Loosening of any component was rare in both arthroplasty types. The HR for revision of stemless total shoulder arthroplasty was 1.00 (95% CI: 0.63–1.61, p = 0.99), with stemmed total shoulder arthroplasty as reference. Male gender (HR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.06–2.13, p = 0.02) and previous surgery (HR = 2.70; 95% CI: 1.82–4.01, p < 0.001) were associated with an increased risk of revision. The authors concluded that the short-term survival of total stemless shoulder arthroplasty was comparable to that of total stemmed shoulder arthroplasty, but also that a longer observation time is needed to confirm whether they would continue to perform equally [13].

Outcome of revision arthroplasties

The outcome of 107 revision arthroplasties for failed resurfacing hemiarthroplasty reported to the DSR from 2006 to 2012 showed a mean WOOS score of 61. The mean WOOS score after anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty for failed resurfacing hemiarthroplasty was 68, which was significantly lower than the WOOS score of 79 found for primary anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty. Especially patients who were 55 years or younger had a high risk of poor outcome with revision arthroplasty. Their mean WOOS score was 52 and 62% had a WOOS score below 50. The authors concluded that when resurfacing hemiarthroplasty is used for osteoarthritis, revision cannot be counted upon as a fallback [14].

Discussion

Publications from the DSR have described inferior patient-reported outcomes and a high revision rate of resurfacing hemiarthroplasty compared with stemmed total shoulder arthroplasty. Total shoulder arthroplasty is now the standard treatment for patients with end-stage osteoarthritis and an intact rotator cuff.

Arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis

In Denmark, resurfacing hemiarthroplasty was the most common arthroplasty for osteoarthritis until 2012. The reason for this is unknown but may be related to concerns about late complications with glenoid loosening and the promising early results of resurfacing hemiarthroplasty. Levy et al. observed similar Constant scores for total resurfacing arthroplasties (n = 39) and resurfacing hemiarthroplasties (n = 30). They hypothesized that resurfacing arthroplasty had the advantage of a bone-preserving design, short operation time, and an easy revision, should the need for revision arthroplasty arise, and they recommended resurfacing hemiarthroplasty for osteoarthritis except in patients with nonconcentric or saddle-shaped erosion of the glenoid [5]. A systematic review published in 2009 supported their results and concluded that resurfacing hemiarthroplasty is a viable option for shoulder replacement, especially in young patients [2].

The DSR observed less promising results with unpredictable and disappointing patient-reported outcomes as well as a high rate of revision especially in young patients. Furthermore, there were poor patient-reported outcomes of revision arthroplasty after failed resurfacing hemiarthroplasty belying the hypothesis of an easy revision [14, 16]. For the past 5 years, the DSR has advocated not using resurfacing hemiarthroplasty for osteoarthritis.

The DSR has advocated not using resurfacing hemiarthroplasty for osteoarthritis

According to the DSR, the most common reason for revision after resurfacing hemiarthroplasty was glenoid wear [16]. This indicates that the rates of revision could have been improved if a glenoid component had been used. However, glenoid exposure with an intact humeral head is difficult and associated with a high risk of neurological complications [8], and total resurfacing arthroplasty has only been used in very few cases during the existence of the DSR.

Anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty is now the most common type of arthroplasty for osteoarthritis in Denmark. Data from the DSR and NARA have shown superior patient-reported outcomes 1 year postoperatively and low rates of revision for anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty compared with hemiarthroplasty. This supports the findings and conclusions of a systematic review [18] and the guidelines of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons [4] recommending anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis in patients with an intact rotator cuff.

In the NARA dataset there was no difference in short-term survival rates between stemmed total shoulder arthroplasty and stemless total shoulder arthroplasty. Very few studies have compared the two arthroplasty types and none of them has been able to find any statistically significant differences in functional outcome scores [1, 17, 19]. Thus, it seems that stemmed total shoulder arthroplasty and stemless total shoulder arthroplasty perform equally and that the choice of the humeral component can be based on the surgeon’s preference. However, this needs to be confirmed by a large randomized clinical trial with long-term follow-up.

Other national registries have examined how the method of fixation and bone morphology of the glenoid can influence the longevity of the arthroplasty. The New Zealand Joint Registry included 1596 total shoulder arthroplasties with 1065 (67%) cemented and 531 (33%) uncemented glenoid components. The revision rate was 4.4 times higher for uncemented glenoid components than for cemented components [3]. A similar study was published by the Australian Joint Registry, in which Page et al. included 10,805 total shoulder arthroplasties for osteoarthritis with 7646 (71%) cemented and 3159 (29%) uncemented glenoid components. The 10-year cumulative revision rate was approximately 7% and 22%, respectively. The HR for revision was 4.77 for uncemented glenoid components, with the cemented component as the reference [7].

Benefits of a national registry

One of the greatest advantages of registry studies is their ability to undertake comprehensive long-term follow-up, and because of the large numbers studied, differences in arthroplasty survival rates can be analyzed with sufficient statistical power. This is rarely possible in randomized clinical trials and longitudinal studies where the limited number of patients and the low number of revision arthroplasties make it difficult to find any statistically significant differences between arthroplasty types. Furthermore, because of the large number of patients studied, it is also possible to estimate HRs as a measure of the risk of revision and thereby compare subgroups of arthroplasty types with adjustment for gender, age, and other factors that might influence the risk of revision. Finally, registry studies can report rare events such as a specific reason for revision. This could include the risk of revision because of infection or the risk of loosening for anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty.

In registry studies there is no control over who is included and what type of arthroplasty is used for a specific indication, and because the patients are not randomly allocated, there is the possibility of different distributions of covariables that could influence the outcome. This makes registry studies unsuitable for comparing treatment effect between arthroplasty types. However, the patients in randomized clinical trials and longitudinal studies are often operated on by a few experienced surgeons and the results cannot always be reproduced by other surgeons. By contrast, registry studies report the outcome of arthroplasty surgery performed by all surgeons on a national or even multinational level. This adds high external validity to the registry studies. Furthermore, in randomized clinical trials it can be laborious and difficult to study differences in outcome between arthroplasty types in smaller subgroups such as in young patients.

Methodological considerations

We acknowledge the limitations inherent to registry studies. The decision to use a specific implant type might be based on factors that are not recognized by the registry: comorbidity; functional demands; glenoid wear; rotator cuff status; and whether the bone stock of the glenoid is considered too poor for a glenoid implant. This might lead to selection bias. Another limitation of the DSR is the lack of a preoperative WOOS score. Any differences in preoperative WOOS score between the arthroplasty types might influence the WOOS score at 1 year. Furthermore, not all patients returned a complete WOOS questionnaire, and any systematic differences in WOOS between responders and nonresponders would have an influence on the results and their interpretation. Finally, incorrect reporting may diminish the accuracy and reliability of the registry data.

The inclusion of bilateral procedures in the survival analyses violates the assumption of independency, but this is probably of minor practical relevance. Another concern is that when arthroplasty survival rates are reported, patients are censored and no longer at risk of revision if they die or emigrate. This violates the assumption of competing risk. The Cox regression model is, however, recommended when reporting HRs after arthroplasty surgery. Even so, statistical limitations are worth considering when the results are interpreted.

Practical conclusion

-

The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry (DSR) has observed significant changes in Danish surgeons’ approach to patients with osteoarthritis.

-

The reason for the increased use of anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty is unknown but may be related to surgeons’ awareness of clinical results through annual reports and peer-review publications from the DSR.

-

The increased use of anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty has significantly improved the nationwide outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis.

-

Today, we regard anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty as the gold standard in the treatment of osteoarthritis in patients with an intact rotator cuff.

-

Information about stemless total shoulder arthroplasty is sparse, but this type of arthroplasty seems to yield similar results to stemmed total shoulder arthroplasty.

References

Berth A, Pap G (2013) Stemless shoulder prosthesis versus conventional anatomic shoulder prosthesis in patients with osteoarthritis: a comparison of the functional outcome after a minimum of two years follow-up. J Orthop Traumatol 14(1):31–37

Burgess DL, McGrath MS, Bonutti PM, Marker DR, Delanois RE, Mont MA (2009) Shoulder resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91(5):1228–1238

Clitherow HD, Frampton CM, Astley TM (2014) Effect of glenoid cementation on total shoulder arthroplasty for degenerative arthritis of the shoulder: a review of the New Zealand National Joint Registry. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 23(6):775–781

Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, Freehill MQ, Stanwood W, Wiater JM, Watters WC III, Goldberg MJ, Keith M, Turkelson CM, Wies JL, Anderson S, Boyer K, Raymond L, Sluka P (2010) Treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 18(6):375–382

Levy O, Copeland SA (2004) Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty (Copeland CSRA) for osteoarthritis of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 13(3):266–271

Lo IK, Griffin S, Kirkley A (2001) The development of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for osteoarthritis of the shoulder: The Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 9(8):771–778

Page RS, Pai V, Eng K, Bain G, Graves S, Lorimer M (2018) Cementless versus cemented glenoid components in conventional total shoulder joint arthroplasty: analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 27(10):1859–1865

Raiss P, Weiter M, Sowa B, Zeifang F, Loew M (2015) Results of cementless humeral head resurfacing with cemented glenoid components. Int Orthop 39(2):277–284

Rasmussen JV, Brorson S, Hallan G, Dale H, Aarimaa V, Mokka J, Jensen SL, Fenstad AM, Salomonsson B (2016a) Is it feasible to merge data from national shoulder registries? A new collaboration within the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 25(12):e369–e377

Rasmussen JV, Hole R, Metlie T, Brorson S, Aarimaa V, Demir Y, Salomonsson B, Jensen SL (2018) Anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty used for glenohumeral osteoarthritis has higher survival rates than hemiarthroplasty: a Nordic registry-based study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 26(5):659–665

Rasmussen JV, Jakobsen J, Brorson S, Olsen BS (2012) The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry: clinical outcome and short-term survival of 2,137 primary shoulder replacements. Acta Orthop 83(2):171–173

Rasmussen JV, Jakobsen J, Olsen BS, Brorson S (2013) Translation and validation of the Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder (WOOS) index—the Danish version. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 4:49–54

Rasmussen JV, Harjula J, Arverud E, Hole R, Jensen SL, Brorson S et al (2019) The short-term survival of total stemless shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis is comparable to that of total stemmed shoulder arthroplasty: a Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.01.010

Rasmussen JV, Olsen BS, Al-Hamdani A, Brorson S (2016b) Outcome of revision shoulder Arthroplasty after resurfacing Hemiarthroplasty in patients with Glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 98(19):1631–1637

Rasmussen JV, Polk A, Brorson S, Sorensen AK, Olsen BS (2014a) Patient-reported outcome and risk of revision after shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis. 1,209 cases from the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry, 2006–2010. Acta Orthop 85(2):117–122

Rasmussen JV, Polk A, Sorensen AK, Olsen BS, Brorson S (2014b) Outcome, revision rate and indication for revision following resurfacing hemiarthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the shoulder: 837 operations reported to the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry. Bone Joint J 96-B(4):519–525

Razmjou H, Holtby R, Christakis M, Axelrod T, Richards R (2013) Impact of prosthetic design on clinical and radiologic outcomes of total shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 22(2):206–214

Singh JA, Sperling J, Buchbinder R, McMaken K (2011) Surgery for shoulder osteoarthritis: a Cochrane systematic review. J Rheumatol 38(4):598–605

Uschok S, Magosch P, Moe M, Lichtenberg S, Habermeyer P (2017) Is the stemless humeral head replacement clinically and radiographically a secure equivalent to standard stem humeral head replacement in the long-term follow-up? A prospective randomized trial. J Shoulder Elb Surg 26(2):225–232

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J.V. Rasmussen and B.S. Olsen receive institutional support (study sponsorship) from DePuy Synthes (Leeds, UK) and B.S. Olsen receives speaker’s fees from Zimmer Biomet (Winterthur, Switzerland).

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies performed were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasmussen, J.V., Olsen, B.S. The Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry. Obere Extremität 14, 173–178 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11678-019-0524-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11678-019-0524-2