Abstract

The thermodynamic functions of the pure Co were assessed using CALPAHD method for the third generation thermodynamic databases. To model the magnetic properties of the cobalt, a two-state magnetic model was accounted for the fcc phase. Calculated results were compared with the experimental information and a good fit to the experimental data was achieved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Proposing a set of thermodynamic functions with a solid physical base to accurately describe the desired physical properties of materials is one of the targets of the Calphadians. To achieve this goal, efforts have been made to develop the third generation of thermodynamic databases based on the Einstein or Debye model of the heat capacity.[1,2,3,4] The descriptions of the pure elements, as the basis of the databases, have been evaluated using a combination of the Einstein/Debye model and polynomials or the segmented models.[5,6,7,8,9,10] The transition metals such as Fe, Co, Mn who occupy the center position of the periodic table are of special interest because many of them have intriguing magnetic properties. The magnetic heat capacity and magnetic Gibbs energy of most elements could be well described by the widely used Inden–Hillert–Jarl (I–H–J) model[11,12] while a few exceptional cases may not be. For this reason, Chen and Sundman applied the two-state magnetic model describing the magnetic properties of fcc iron to make sure the fcc Fe turn stable at 1185 K.[4] Before this, the two-state model has been introduced in the CALPHAD assessments by Kaufman[13] and Weiss[14] to model the magnetic behaviors of Fe, Mn and Cr. Miodownik has extended this model to the Fe-Ni-Cr ternary system.[15]

Co, as a member of the transition metals, also has anomalous magnetic property. There is a discrepancy between the value of the magnetic moment determined by the magnetic experiments (~ 1.7)[16,17,18,19,20] and the one derived from the thermochemical information (~ 1.3).[21,22] The value of previous one is too large to fit the peak of the magnetic heat capacity so the later one which is called ‘thermochemical moment’ was always preferred in the CALPAHD assessment. Miodownik suggested that the concept of two magnetic states might be a promising candidate to resolve this conflict.[23] Besides, ab initio calculations[24] indicated that there are two magnetic states in fcc cobalt which is similar to fcc iron, with the large volume, large magnetic moment state lying lower and the large volume, large magnetic one lying upper. Furthermore, Bendick and Pepperhoff[25] found similarities between pure fcc cobalt and fcc iron alloys experimentally by revealing their anomalies in electrical resistivity. These findings make it possible to introduce the two-state magnetic model to the pure Co. The use of the two-state magnetic model could provide more flexibility on assessing the magnetic properties of Co. In the present workwe employ the two-state magnetic model to describe the existence of two magnetic states in fcc Co. To resolve the discrepancy between two magnetic moment values, the value obtained by the magnetic experiments was accepted in the present assessment to fit the thermochemical data. A consistent thermodynamic description of pure Cowas achieved and the fit to the experimental data is reasonably good.

2 Thermodynamic Modeling

The thermodynamic models adopted in this work were firstly proposed in the 1995 Ringberg unary workshop[1,2,3,26] and then developed and applied to Fe by Chen and Sundman.[4] These new models provide a theoretical framework for the construction of the new generation of CALPHAD databases. Some assessments of the elements have been performed based on these models.[5,6,8] The Einstein model lays the foundation of the framework. The heat capacity of a solid substance can be described by its combination with the polynomials (see Eq 1).

The first term on the right side is the main constitute of the heat capacity which represents the contribution from the Einstein model describing the harmonic vibration of the lattice. The theta denotes the Einstein temperature. The second and third terms indicate the contribution from the electronic excitation and the anharmonic vibration. The value of n could be chosen as 2, 3 or 4 depending on the shape of the heat capacity and it is possible to use two of them simultaneously if necessary. The magnetic heat capacity is described by the last term. The model for the magnetism used in the present work is a slightly revised version of the I-H-J model.[11,12] The details of this modified model could be found in the literature.[4,6] The Gibbs energy could be calculated from the heat capacity correspondingly (see Eq 2).

The sum of the first two terms on the right side describes the zero-point energy of the substance. The third one represents the contribution from the Einstein model. The fourth, fifth and sixth terms are derived from the second, third and fourth terms in Eq 1 respectively.

As mentioned in the introduction section, a two-state model[13,15,27] was applied to describe the magnetic properties of fcc Co. This model postulates that there are two states coexisting in one phase-one state with higher energy and another with lower. The energy gap between these two states is ΔE. The excitation between the two states could cause an extra contribution to the Gibbs energy which can be expressed as:

ΔE is the energy difference between the two states which is described as a function of temperature. g2/g1 indicates the degeneracy ratio of the two states. A and B are parameters to be optimized.

The contribution to the enthalpy and entropy could be written as:

With increasing degeneracy ratio, the value of the enthalpy decreases while the entropy increases. The increase of the energy gap will lead to the increase of the enthalpy and the decrease of the entropy.

The contribution to the heat capacity could be represented as:

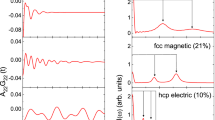

The shape of the heat capacity could be seen in Fig. 1. For the two-state magnetic model, it might be considered as a correction to the magnetic heat capacity described by the I–H–J model.[11,12] From the authors’ experiences, the value of the degeneracy ratio controls the height of the peak and the energy gap dominates the width of the peak.

A generalized two-state model[2] was used for the modelling of the liquid-amorphous phase. In this model, the atoms can be occupied in either a liquid-like state or a solid-like state and the degeneracy ratio is set as 1. The liquid-like atoms have transitional degrees of freedom while the solid-like atoms have vibrational degrees. This hypothesis helps explain the phenomenon called ‘amorphous solidification’.[2] The Gibbs energy of the liquid-amorphous phase is thus defined as:

ΔGd is the energy gap between the liquid-like state and the solid-like state. oGliq-am and oGam could be thought of as the Gibbs energy of the phase when all the atoms were in each state. The thermodynamic function of oGam is identical to that of the solid phase except for the exclusion of the quartic term. ΔGd is written as follows:

where A, B and C are the parameters to be assessed. B, referred to as the communal entropy, is suggested to set as a value comparable to − R which is the gas constant.

In the new models, an empirical method was designed to describe the temperature range which is above the melting temperature. The aim is to prevent the solid phase being stable again at very high temperature. This method can guarantee the consistency of the desired thermodynamic properties at the melting point thus a smooth curve in each property diagram. The details of this method were well demonstrated in Ref 4 and will not be discussed in this work.

3 Experimental Information and Optimization Procedure

The available experimental information on pure Co has been summarized in Ref 21, 28 and more recently in Ref 6. The experimental results accepted in the assessment[6] were also adopted in the present work except for (1) the value of the magnetic moment of each phase (2) the range of the hcp/fcc transition enthalpy and fcc/liquid transition enthalpy (3) the Curie temperature of the hcp phase. In this work, the value of beta for all stable phases of pure Co (hcp, fcc and liquid-amorphous phase) are set to 1.7 which fall within the range of magnetization measurement results.[16,17,18,19,20] In this work, the value 400 ± 40 J/mol for the enthalpy of hcp/fcc transition according to the Guillermet’s work[21] was accepted. The value 15,690 ± 1200, reported from the drop calorimetric data by Kubaschewski,[29] was adopted for the enthalpy of the fcc/liquid transition. The value of 1396 K, suggested by Guillermet,[21] was adopted as the Curie temperature for hcp phase. Due to the lack of available data, we accepted the degeneracy ratio value (1.35) of fcc Fe in Ref 4 and fixed the degeneracy ratio of fcc Co as the same value in the present work.

The assessment in the present work was performed using the PARROT module implemented in the Thermo-Calc software package.[30] As the stable phase at room temperature, the hcp phase was assessed firstly to fit the experimental heat capacity. Then the parameters of fcc phase were optimized based on the accepted experimental results on the heat capacity and hcp/fcc transition temperature and enthalpy. The assessment of the liquid-amorphous phase was finalized according to the adopted enthalpy and temperature of fusion.

4 Results and Discussions

The model parameters optimized in the present work are listed in Table 1. The calculated heat capacity of hcp Co, compared with the SGTE description,[22] experimental data,[25,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] and the evaluated data[31] is plotted in Fig. 2. Two heat capacity curves are quite close at the temperature range from 300 to 1000 K. A good agreement with the experimental data was achieved. It could be seen from the figure that the peak of the magnetic heat capacity assessed in the present work is much higher than that of the SGTE description. The height of the peak was determined by the value of the magnetic moment (beta), one of two adjustable parameters in the I–H-J model,[11,12] and a larger beta value will lead to a higher peak. Another adjustable parameter, Curie temperature (Tc) controls the location of the peak. A detailed heat capacity curve from 0 to 300 K is showed together with the experimental data[32,33] and the evaluated data[31] in Fig. 3. The calculated result could reproduce the determined data points reasonably well. It is attributed to the adoption of the Einstein model where the Einstein temperature is the only parameter to be determined. The evaluated Einstein temperatures in this work are compared with the ones obtained from other sources in Table 2.[6,25,39,40,41,42] The Debye temperature that is more often found in the literature can be converted to the Einstein temperature by using a simple relation ϴE = 0.7143 ϴD.[43] The heat capacity curve of fcc Co is calculated and plotted together with the SGTE description,[20] the experimental data[25,33,34,36,37,38,44] and the assessed data[31] in Fig. 4. Although the present description has a higher peak at the magnetic transition temperature, its fit to the experimental data is comparable to the fit made by the SGTE description.[22] As mentioned above, there are only two adjustable parameters in the I–H–J magnetic model. This limitation makes it extremely difficult to fit the magnetic heat capacity with a much higher beta value just using the parameters in the I–H–J model.[11,12] The Fig. 5 shows the calculated magnetic heat capacity of fcc Co. The black solid line depicts the total magnetic heat capacity which consists of two parts. One part is the area below the red curve depicting the contribution from the two-state magnetic model. Another part is the area between the solid black line and the red line representing the magnetic heat capacity described by the I–H–J model. The latter part was plotted separately by the black dotted line to compare with the total magnetic heat capacity (the black solid line). From the comparison, it could be seen that the addition of the contribution from the two-state magnetic model considerably modifies the shape of the magnetic heat capacity. It changes the height and the width of the peak simultaneously without adjusting any parameters in the I–H–J model. In I–H–J model, the width of the peak is determined by a structure-dependent factor p whose value cannot be optimized during the assessment. The two-state magnetic model provides us additional flexibility to accommodate the experimental information on both magnetic moment and the magnetic heat capacity. It could be considered as a good complement for the I–H–J model[11,12] to describe the complicated magnetic properties of the materials. The calculated results indicates that the two-state magnetic model could be a promising way to resolve the discrepancy between the values of β for Co derived from the thermodynamic and magnetic routes.

Comparison between the calculated enthalpy of Co and the experimental data[35,36,37,38,45] as well as the evaluated data[31] is represented in Fig. 6. A good fit to the experimental data was obtained. The calculated entropy of Co was plotted together with the data points derived from the experimental determination[31,35] in Fig. 7. The entropy curve could reproduce the data very well. Some important thermodynamic properties calculated in the present work were summarized in Table 3.

5 Conclusions

We applied the two-state magnetic model to the fcc Co to resolve the discrepancy between the magnetic moment derived from the thermochemical data and from the magnetic measurements. An updated description of pure Co was obtained for the third generation thermodynamic databases. The agreement between the calculated results and the experimental data was reasonably good. It indicates that the two-state magnetic model could be a promising candidate to complement the I–H–J model and to describe the complicated magnetic properties of the transition metals.

References

D. de Fontnine, S.G. Fries, G. Inden, P. Miodownik, R. Schmid-Fetzer, and S.L. Chen, Group 4: λ Transitions, Calphad, 1995, 19(4), p 499-536

J. Ågren, B. Cheynet, M.T. Clavaguera-Mora, K. Hack, J. Hertz, F. Sommer, and U. Kattner, Group 2: Extrapolation of the Heat Capacity in Liquid and Amorphous Phases, Calphad, 1995, 19(4), p 449-480

M.W. Chase, I. Ansara, A. Dinsdale, G. Eriksson, G. Grimval, L. Höglund, and H. Yokokawa, Group 1: Heat Capacity Models for Crystalline Phases from 0 K to 6000 K, Calphad, 1995, 19(4), p 437-447

Q. Chen and B. Sundman, Modeling of Thermodynamic Properties for bcc, fcc, Liquid, and Amorphous Iron, J. Phase Equilibria, 2001, 22(6), p 631-644

S. Bigdeli, H. Mao, and M. Selleby, On the Third-Generation Calphad Databases: An Updated Description of Mn, Phys. Status Solidi (B) Basic Res., 2015, 252(10), p 2199-2208

Z. Li, S. Bigdeli, H. Mao, Q. Chen, and M. Selleby, Thermodynamic Evaluation of Pure Cobalt for the Third Generation of Thermodynamic Databases, Phys. Status Solidi (B) Basic Res., 2017, 254(2), p 1600231

I. Roslyakova, B. Sundman, H. Dette, L. Zhang, and I. Steinbach, Modeling of Gibbs Energies of Pure Elements Down to 0 K Using Segmented Regression, CALPAHD, 2016, 55, p 165-180

S. Bigdeli, H. Ehtehsami, Q. Chen, H. Mao, P. Korzhavy, and M. Selleby, New Description of Metastable hcp Phase for Unaries Fe and Mn: Coupling Between First-Principles Calculations and CALPHAD Modeling, Phys. Status Solidi (B) Basic Res., 2016, 253(9), p 1830-1836

Z. Li, First Step to a Genomic CALPHAD Database for Cemented Carbides – C-Co-Cr Alloys, Ph.D Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2017

A.V. Khvan, A.T. Dinsdale, I.A. Uspenskaya, M. Zhilin, T. Babkina, and A.M. Phiri, A Thermodynamic Description of Data for Pure Pb from 0 K Using the Expanded Einstein Model for the Solid and the Two State Model for the Liquid Phase, CALPAHD, 2018, 60, p 144-155

G. Inden, Computer Calculation of the Free Energy Contribution Due to Chemical and/or Magnetic Ordering, in Proc. Project Meeting CALPHAD, Duesseldorf, 1976, pp. 1-13

M. Hillert and M. Jarl, A Model for Alloying in Ferromagnetic Metals, Calphad, 1978, 2, p 227-238

L. Kaufman, E.V. Clougherty, and R.J. Weiss, The Lattice Stability of Metals—III.IRON*, Acta Metall., 1963, 11(5), p 323-335

R.J. Weiss, A Model for the Electronic Structure of Chromium and α-Manganese, Philos. Mag. B, 1979, 40(5), p 425-428

A.P. Miodownik, The Effect of Two Gamma States on the Free Energy of Austenitic Iron-Nickel-Chromium Alloys, Acta Metall., 1970, 18, p 541-547

W. Betteridge, The Properties of Metallic Cobalt, Prog. Mater. Sci., 1979, 24, p 51-142

J.P. Meyer, P. Taglang, and C.R. Acad, Sur les moments magnétiques et points de curie des variétés hexagonale et cubique du cobalt, Sci. Paris, 1950, 231, p 612

H.P. Myers and W. Sucksmith, The Spontaneous Magnetization of Cobalt, Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., 1091, 1951(207), p 427-446

N. Heiman and N. Kazama, Concentration Dependence of the Co Moment in Amorphous Alloys of Co with Y, La, and Zr, Phys. Rev. B, 1978, 17, p 2215-2220

K.H.J. Buschow, Magnetic Properties of Amorphous Rareearth–Cobalt Alloys, J. Appl. Phys., 1983, 54, p 2578-2581

A.F. Guillermet, Critical Evaluation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Cobalt, Int. J. Thermophys., 1987, 8(4), p 481-510

A.T. Dinsdale, SGTE Data for Pure Elements, Calphad, 1991, 15(4), p 317-425

A.P. Miodownik, Private communication, 2015

J.F. Janak, Itinerant Ferromagnetism in fcc Co, Solid State Commun., 1978, 25, p 53-55

W. Bendick and W. Pepperhoff, Thermally Excited States in Cobalt and Cobalt Alloys, J. Phys. F, 1979, 9(11), p 2185-2194

B. Sundman and F. Aldinger, The Ringberg Workshop 1995 on Unary Data for Elements and Other End-Members of Solutions, Calphad, 1995, 19(4), p 433-436

A.P. Miodownik, The Calculation of Magnetic Contributions to Phase Stability, Calphad, 1977, 1(2), p 133-158

T. Nishizawa and K. Ishida, The Co (cobalt) System, Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr., 1983, 4(4), p 387-390

O. Kubaschewski, P. Brizgys, O. Huchler, R. Jauch, and K. Reinartz, Die Schmelz- und Umwandlungswärmen der Metalle, Z. Elektr, 1950, 54, p 275

J.-O. Andersson, T. Helander, L. Höglund, P. Shi, and B. Sundman, THERMO-CALC & DICTRA, Computational Tools for Materials Science, Calphad, 2002, 26(2), p 273-312

R. Hultgren, P.D. Desai, D.T. Hawkins, M. Gleiser, K.K. Kelley, and D.D. Wagman, Selected Values of the Thermodynamic Properties of the Elements, American Society for Metals, Metals Park, 1973, p 126-133

K. Clusius and L. Schachinger, Ergebnisse der Tieftemperaturforschung IX. Die Atomwärme des Kobalts zwischen 150 und 270° K, Z. Natursch, 1952, 7A, p 185-191

L.D. Armstrong and H. Grayson-Smith, High Temperature Calormetry II. Atomic Heats of Chromium, Mangnese, and Cobalt Between 0 °C and 800 °C, Can. J. Res, 1950, 28A, p 51-59

M. Braun and R. Kohlhass, Die spezifische Wärme des Kobalts zwischen 50 und 1400 °C, Z. Natursch, 1964, 19A, p 663-664

A.S. Normanton, A Calorimetric Study of High-Purity Cobalt from 600 to 1600 K, Metal Sci., 1975, 9, p 455-458

F. Wuest, A. Meuthen, R. Durrer, Die Temperatur-Waermeinhaltskurven der technisch wichtigen Metalle, Forsch. Geb. Ing., Heft 204 (Springer, Berlin, 1918), 1918

S. Umino, Latent Heat of Fusion and the Heat of Transformation of Some Metals, Sci. Rep. Tohoku Univ. Ser. I, 1926, 15, p 597

S. Umino, Heat of Transformation of Nickel and Cobalt, Sci. Rep. Tohoku Univ. Ser. I, 1927, 16, p 593

A.F. Guillermet and G. Grimvall, Homology of Interatomic Forces and Debye Temperatures in Transition Metals, Phys. Rev. B, 1989, 40(3), p 1521-1527

S.M. Shapiro and S.C. Moss, Lattice Dynamics of Face-Centered-Cubic Co0.92Fe0.08, Phys. Rev. B, 1977, 15(5), p 2726-2730

O.P. Gupta, Crystal Dynamics of Face Centered Cubic Cobalt, Solid State Commun., 1982, 42(1), p 31-32

Y. Chuang, R. Schmid, and Y.A. Chang, Magnetic Contributions to the Thermodynamic Functions of Pure Ni, Co, and Fe, Metall. Trans. A, 1985, 16A, p 153-165

G. Cacciamani, Y.A. Chang, G. Grimvall, P. Franke, L. Kaufman, P. Miodownik, J.M. Sanchez, M. Schalin, and C. Sigli, Group 3: Order-Disorder Phase Diagrams, Calphad, 1997, 21(2), p 219-246

V.E. Peletskii and E.B. Zaretskii, Investigation of the Thermal Transport Properties and Temperature Anomalies Near the Curie Points of the Classical Ferromagnets Cobalt and Iron, High Temp. High Press., 1981, 13, p 661-664

F.M. Jaeger, E. Rosenbohm, and A.J. Zuithoff, The Exact Determination of Specific Heat at Elevated Temperatures—XIII. The Specific Heats, the Electronical Resistance and the Thermoelectric Forces of Cobalt, Rec. Trav. Chim, 1940, 59, p 831-856

Acknowledgments

This work was performed within the VINN Excellence Center Hero-m, financed by VINNOVA (Grant Number 2012–02892), the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems, Swedish industry, and KTH Royal Institute of Technology. One of the authors, ZL, is grateful to the China Scholarship Council (CSC) and STT foundation for the financial support. Authors are grateful to late Dr A.P. Miodownik for the helpful advices. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Qing Chen (Thermo-Calc) for the inspiring discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This invited article is part of a special issue of the Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion in honor of Prof. Zhanpeng Jin’s 80th birthday. The special issue was organized by Prof. Ji-Cheng (JC) Zhao, The Ohio State University; Dr. Qing Chen, Thermo-Calc Software AB; and Prof. Yong Du, Central South University.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Mao, H. & Selleby, M. Thermodynamic Modeling of Pure Co Accounting Two Magnetic States for the Fcc Phase. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 39, 502–509 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11669-018-0656-x

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11669-018-0656-x