Abstract

This paper investigates the fatigue performance of Nitinol thin-film devices used in medical applications. Freestanding films are fabricated and structured by microsystem technology processes (magnetron sputtering, UV lithography and wet chemical etching). A test rig is developed to address the requirements of Nitinol thin-film samples in terms of force, stroke and precision and also allows the multiplication of test rigs due to its inexpensive components. Hence, several samples can be tested simultaneously at different parameters in order to obtain a thorough characterization within reasonable test duration. Finite element analysis (FEA) is used to derive maximum principle strains of test specimen during cycling loading. Therefore, a superelastic, multiaxial material model with two different kinetic transformation mechanisms being capable of considering tension/compression asymmetry and temperature effects is realized and implemented using the FEA software Comsol Multiphysics. Good agreement between simulation and experimental tensile tests is shown. An excellent fatigue resistance with a high fatigue safety limit of 1.75% pulsatile strain amplitude for mean strains up to 2.5% with sputtered Nitinol diamond specimen is observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitinol is without a doubt a material with fascinating properties. Its martensitic transformation enables the reversible accommodation of strains in the range of several percents, for either spring or actuator applications, and is the underlying mechanism to superelasticity and the shape memory effect (Ref 1). Besides academic interest, it is also one of the most important materials in the medical field, in particular for devices or implants that can be deployed in a minimal-invasive manner. Its most prominent application is the stent, which is used for the treatment for vascular diseases, e.g., stenosis, to avoid stroke, carotid artery disease (CAD), peripheral artery disease (PAD), etc. (Ref 2, 3). A crucial parameter for vascular devices is their material fatigue due to the pulsatile movement of the vessels during the device operation. The literature is rich on fatigue tests and theoretical predictions for Nitinol fatigue (Ref 4,5,6,7,8,9). Major factors influencing the fatigue life of Nitinol are the material impurity level (in particular, the size of oxide and carbide inclusion) (Ref 10), working temperature (difference between martensitic transformation temperature and test temperature) (Ref 11, 12) and microstructural aspects (grain size, amount, size and distribution of Ni4Ti3 precipitates). The performance of the Nitinol alloy at specific test parameters can be presented in a kind of Wöhler diagram, from which the materials safety limit can be derived. For standard Nitinol (processed by laser cutting or braiding) (Ref 6), the safety limit is in the range of 0.5-0.6%, for a large interval of mean strains (Ref 13). Most often, diamond-shape specimen resembling a single stent cell or Nitinol wires are used for fatigue testing of Nitinol. Due to the geometric complexity of these subcomponents, FEA simulations are necessary to calculate the dynamic mechanical behavior.

A Nitinol fabrication route based on microsystem technology (MST) processes is used (Ref 14), offering novel design freedom with a very pure Nitinol alloy. For instance, it enables the fabrication of miniaturized Nitinol devices with highly complex geometries (e.g., devices with complex topographical features: Nitinol stents with drug reservoirs, cavities or interface features, thin Nitinol meshes with a few micrometer mesh sizes for tissue engineering), devices with integrated functionality (e.g., Nitinol stent structures equipped with Pt, PtIr or IrOx electrodes for bioelectric sensing or stimulation, devices with a large number of Ta markers), etc. (Ref 15,16,17). Hence, numerous next-generation medical devices can be envisioned. However, the fatigue properties of these devices and material systems need to be considered and tested. Also, the microstructure of these sputtered Nitinol devices differs in a way that oxide and carbide inclusions are lacking, and no cold work is required to structure and shape these devices. These features promise much improved fatigue properties, and a first study on thin-film Nitinol showed a significantly higher safety limit of 1.5% (Ref 18) in alternating strain. In addition, new alloys such as ultralow fatigue shape memory materials from TiNiCu (Ref 19) and TiNiCuCo (Ref 20) can be easily fabricated, structured and shape set using the MST processes.

The parameter set for fatigue tests includes different strain amplitudes and mean strains, and each data point requires multiple samples to increase statistical significance. Disregarding test parameters of the alloy itself (purity, microstructure, chemical composition, transformation temperature), additional external test parameters can be test temperature, test frequency, testing media (air, air-cooled, water, PBS, oil, etc.). This leads to a high number of samples required for a meaningful fatigue test. Typically, Nitinol shape memory alloys are tested at 20 Hz, a compromise between experiment duration and the detrimental effects that occur due to self-heating and -cooling during the martensitic transformation, i.e., the increase in stress plateau slope (Ref 21). At 20 Hz, a typical test run-out of 100 Mio. cycles required for FDA approval, which corresponds to almost three years in operation only, takes almost 60 days. Given the high number of samples to test, strategies are required to decrease the overall testing time. Obviously, multisample holders for testing several samples simultaneously at the same parameter set and multiple test rigs for different parameter sets can be used. The requirements for fatigue tests of Nitinol thin-film specimen of different shapes are, however, quite demanding: The amplitude of the cyclic movement needs to be precise within ± 5 µm for amplitudes between ~ 80 µm and ~ 500 µm, and forces vary for different sample shapes between a few milli-Newton for diamond-shape specimen to a few tens of Newton for full material. Piezoelectric actuators offer such high-precision movement, but both high amplitudes and high forces are challenging for this actuator class. In addition, tests need to be conducted at body temperature, preferably in biologic liquid to simulate the operating environment of the final device. Commercially available, elaborate fatigue testing machines that fulfill these requirements require a high budget and cannot be multiplied easily in order to test different parameters simultaneously.

Therefore, the scope of this work was the development of an accurate, simple and economically scalable high-cycle fatigue testing rig for thin-film Nitinol-based specimen. These are fundamental to test and evaluate the performance of different final devices that can be fabricated by the described MST process (e.g., different materials, material stack, geometry variations, heat treatments, etc.). In contrast to previous results presented in (Ref 18), we determine the fatigue behavior of sputtered Nitinol thin-film devices for an increased number of 10 Mio. pulsatile cycles and a large number of mean strain/strain amplitude combinations, which has not yet been reported in this detail yet, and are able to do so for other more complex final devices in the future. It also allows for a significant comparison to studies on Nitinol fabricated by other methods. In order to derive strain amplitudes from the absolute displacement of the sputtered diamond-shape specimen, a FEA model was implemented in Comsol to account for sputtered Nitinol material parameters. The FEA model also allows to calculate principle strains in sputtered Nitinol for more complex 3D geometries.

Experiment

Fatigue Test Rig

The fatigue testing rig developed in this work is sketched in Fig. 1. Its basic working principle is the spring/mass system. Two springs are compressed by a deadweight of specific mass. The deadweight is connected downward to the upper clamping jaw, and the lower clamping jaw is initially fixed. Hence, the spring/mass system has a resonant frequency that is determined by the spring constants, the mass of the deadweight and the elasticity of the sample at a given preload. For diamond-shape specimen which is highly flexible and which exhibits low tensile or compressive forces, the system is mainly determined by the mass and the spring constants. Mass and spring constants are chosen so that the systems’ resonant frequency is 20 Hz.

The system is actuated using a voice coil actuator (ACCEL, VLR0033-0099-00A). A rectangular signal is used to drive the voice coil actuator and excite the system at its resonant frequency. During a period of T/2, the signal at the voice coil is high and low, respectively. The absolute values of the high and low signal determine the amplitude of the oscillation, and the mean strain can also be adjusted within a limited range. The amplitude is controlled by a PID control implemented on an Arduino Due microcontroller. The mean strain is controlled by incremental/decremental steps after each period. The movement is measured using an analog inductive sensor (IFM, IF6029), whose signal is fed to one of the Arduino’s analog input ports.

The system has several benefits: In resonance, the movement is almost perfectly sinusoidal, which is important for the comparison with results of other studies. An amplitude stability of ± 5% (of the nominal amplitude) can be reached. The voice coil actuator requires low power, generates no obvious heat and is cheap.

However, some issues that occur during fatigue testing of Nitinol need to be addressed: During cycling at a given initial mean strain, the effective elastic modulus of the material changes, influencing the resonant frequency of the system. Additionally, when stress levels drop during cycling, the mean strain increases due to the use of the spring/mass principle, which is force controlled rather than strain controlled. The effect of resonant frequency change can be handled by changing the excitation amplitude accordingly, which can be implemented in the Arduino C++ code. However, while testing 30-µm-thick full material, the resonant frequency remains stable within 0.2 Hz, so that the change in excitation amplitude to keep the oscillation constant is rather small. The effect of increasing mean strain, however, requires additional measures, since it cannot be purely accommodated by changing the values of the voice coils high and low signal. We added a linear motor to the system, which changes the position of the lower clamping jaw, so that the mean distance between upper and lower clamping jaw remains constant throughout the experiment.

The test rig was constructed so that samples could be placed within a temperature-controlled deionized water basin with a constant temperature at 37 °C.

Experimental Procedure

For fatigue and tensile tests, samples fabricated by the previously described MST methods were used. Dogbone specimen as shown in Fig. 2 (left) with a parallel length of 13 mm × 0.5 mm is used in tensile tests to determine the material parameters experimentally used in the FEA simulations. The so-called diamond-shape specimen as shown in Fig. 2 (left) is used in tensile tests for the validation of the FEA simulations and the determination of the high-cycle fatigue behavior. After fabrication, the diamond specimen was surface treated. The SEM image in Fig. 2 (right) shows a typical resulting surface of a Nitinol strut. Both dogbone and diamond specimens have a thickness of 50 µm.

Finite Element Formulation and Analysis

To calculate mean strain and strain amplitude of the diamond specimen under various pulsatile loading conditions, a multiaxial SMA material model was implemented into the FEA software Comsol Multiphysics. The main principle was adapted from Thiebaud et al. (Ref 22, 23), and the interactions between the different modules are visualized in Fig. 3.

Structural Mechanics

Two structural mechanics modules \(\widetilde{SM}\) (linear resolution) and \(SM\) (nonlinear resolution) are used whereupon the evolution law

is solved in the linear module \(\widetilde{SM}\) with \(\rho\) the density, \(\underline{{\widetilde{\sigma }}}\) the stress tensor and the displacement vector \(\widetilde{\varvec{u}}\). Here, stress and strain are connected by the linear constitutive relation

with the linearized small strain tensor \(\underline{{\widetilde{\varepsilon }}}_{{(\widetilde{\varvec{u}})}}\) and the isotropic stiffness tensor \(\underline{\underline{{\tilde{C}}}}\) assuming a constant Poisson ratio and a constant phase-averaged Young’s modulus

of the reciprocal martensite and austenite Young’s moduli EM and EA. These are determined experimentally from the linear parts of the dogbone specimens’ stress–strain relation in Fig. 5 where the martensite transformation has not started or has been completely finished, respectively. The result of the linear structural mechanics module \(\widetilde{SM}\) is used for the construction of the components \(\widetilde{K}_{ij}\) of the eigenstrain tensor \(\widetilde{{\underline{K} }}\) defined as

with \(\varepsilon_{\text{Tr}}\) the transformation strain, the normalized stress tensor \(\widetilde{{\underline{N} }}\), \(\underline{I}\) the tensor identity and the function f to describe tension–compression asymmetry. Therefore, the transformation strain is found to be reasonably constant below austenite finish temperature Af (Ref 24) and decreases with rising temperature T and is thus defined as follows:

with \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{Tr}},\hbox{max} }}\) the transformation strain and \(\varepsilon_{\text{red}}\) the transformation strain reduction factor.

The asymmetry function is chosen as

with a the asymmetry factor. The quantity \(\widetilde{y}_{0}\) and the tensor \(\widetilde{{\underline{N} }}\) are chosen as

with \(\widetilde{{\overline{\sigma } }}\) the Von Mises stress. The resulting eigenstrain tensor \(\widetilde{{\underline{K} }}\) from the linear solid mechanics module \(\widetilde{SM}\) is coupled to the constitutive relation

of the nonlinear solid mechanics module \(SM\). Here, the phase-averaged Young’s modulus

of the reciprocal martensite and austenite Young’s moduli \(E_{\text{M}}\) and \(E_{\text{A}}\) is defined as a function of the local martensite fraction \(\xi_{\text{M}}\) and austenite fraction \(\xi_{\text{A}} = 1 - \xi_{\text{M}}\). The structural mechanics modules \(\widetilde{SM}\) and \(SM\) are solved for identical geometry and boundary conditions. In contrast to (Ref 22, 23), we have used the Green strain tensor (Ref 25) \(\underline{E}_{{\left( \varvec{u} \right)}}\) and its quadratic components \(\underline{q}_{{\left( \varvec{u} \right)}}\), respectively, to allow for large geometric deformations. The difference between the results using the linearized small strain tensor \(\underline{\varepsilon }_{{\left( {\widetilde{\varvec{u}}} \right)}}\) and the Green strain tensor \(\underline{E}_{{\left( \varvec{u} \right)}}\) is shown in Fig. 7. A much improved approximation between tensile and compression measurements of diamond specimen and corresponding FEA results is obtained using the Green strain tensor. Both structural mechanics modules are implemented for 2D problems with plane stress assumptions neglecting possible out-of-plane movement of the diamond specimen under compression.

Kinetic Transformation

The kinetic transformation from martensite to austenite is calculated in an additional partial differential equation (PDE) module. Therefore, the equivalent stress \(\sigma_{\text{eq}}\) defined as follows:

is provided by the nonlinear structural mechanics module to calculate the transformation rates with respect to the tension–compression asymmetry. In contrast to the transformation law presented in Ref 22, 23, we have implemented two different constitutive transformation laws originated by Brinson (Ref 24, 26) (BRI) and Müller–Achenbach–Seelecke (Ref 27,28,29) (MAS). Figure 4 schematically illustrates the critical stresses of the transformation paths for pseudoelastic material behavior from austenite to detwinned martensite (A → M) and back from detwinned martensite to austenite (M → A) as a function of temperature. The critical start and finish stresses \(\sigma_{\text{cr,s}}\) and \(\sigma_{\text{cr,f}}\), the martensite and austenite start and finish temperatures \(T_{\text{Ms}}\), \(T_{\text{Mf}}\), \(T_{\text{As}}\) and \(T_{\text{Af}}\) and the Clausius–Clapeyron coefficients \(C_{\text{AM}}\) and \(C_{\text{MA}}\) used for the FEA are experimentally determined by tensile tests of dogbone specimen at different temperatures and additional DSC measurements. The resulting material parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Transformation: Brinson (BRI)

The uniaxial transformation law and its activation condition presented by Brinson et al. (Ref 24) are

for the transformation from detwinned martensite to austenite and

for the transformation from austenite to detwinned martensite, respectively. Here, \(\xi_{{{\text{MA}}0}}\) and \(\xi_{{{\text{AM}}0}}\) are the initial or reinitial values of the transformation processes and described according to the following equations:

for the transformation from detwinned martensite to austenite and

for the transformation from austenite to detwinned martensite, respectively. In the PDE module, the evolution law

is solved at which the activation conditions are implemented as Boolean expressions.

Transformation: Müller–Achenbach–Seelecke (MAS)

For the implementation of the MAS transformation law, we used the approximative formulas

presented by Wendler et al. (Ref 29) with \(V_{\text{D}}\) the transforming layer volume, \(k_{\text{B}}\) the Boltzmann constant and \(\tau\) the relaxation time constant which represent the original formulations very well and accelerate the numerical computation. For the critical transformation stresses \(\sigma^{\text{MA}}\) and \(\sigma^{\text{AM}}\), we choose the mean values between start and finish temperatures \(T_{\text{As}}\) and \(T_{\text{Af}}\) and critical start and finish stresses \(\sigma_{\text{cr,s}}\) and \(\sigma_{\text{cr,f}}\), respectively, as follows:

In the PDE module, the evolution law

is solved for the MAS transformation at which the activation conditions are again implemented as Boolean expressions.

Temperature Evolution

Ambient temperatures and heat flow effects can by examined by the temperature module solving the heat equation

with \(\rho\) the density, \(c_{\text{p}}\) the heat capacity and the thermal conductivity \(k_{{\left( {\xi_{\text{M}} ,\xi_{\text{A}} } \right)}}\) defined as the reciprocal phase average

of the phase-dependent thermal conductivities \(k_{\text{M}}\) and \(k_{\text{A}}\) for martensite and austenite, respectively. Self-heating and self-cooling of the material due to the phase transformation can be included in the heat equation using a heating source defined as

with the transformation enthalpy \(\Delta h_{{\left( {\sigma_{\text{eq}} } \right)}}^{\text{AM}}\). The transformation enthalpy considering the standard latent heat of entropic origin and stress-dependent contributions is given by (Ref 29, 30):

with L the latent heat. Nevertheless, the temperature variations due to the kinetic transformations are neglected in the following simulations, and thus an isothermal behavior (T = T0) is considered.

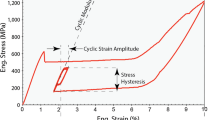

Experimental Validation

In this section, we validate the model implementation by comparing simulation results with corresponding experimental results. At first, we consider the results of the uniaxial tensile tests which we have used to determine the material parameters relevant to the phase transformation as mentioned before. The resulting stress–strain behavior of the dogbone specimen is shown in Fig. 5 for ambient temperatures of T = 22 °C (left) and T = 37 °C (right). The simulation results using both the BRI and MAS transformation laws show nearly identical pseudoelastic behavior corresponding well with the measurements. However, the plateau slope using MAS transformation law is flat, in contrast to a slight slope which depends on the critical start and finish stress values used in the BRI transformation law.

Next, we use the finite element model with the MAS transformation law and the verified material parameters to predict the superelastic material behavior of sputtered diamond specimen. The result of the stress distribution at a temperature of T = 22 °C in the strut close to the apex of the diamond specimen under tensile and compressive displacement of 400 µm in y direction is shown in Fig. 6 (left). Under tensile displacement, the stresses’ x-component \(\sigma_{x}\) is negative (compression) at the outer edges of the strut, positive (tension) at the inner edges and vice versa if a compressive displacement in y direction is applied to the diamond specimen as shown in the upper part of Fig. 6 (left). The resulting martensite fraction is shown in the upper part of Fig. 6 (right). It is clearly seen that locations where high stresses \(\sigma_{x}\) occur correspond well with the locations where the martensitic transformation occurs. The same applies for the stresses’ y-component \(\sigma_{y}\) in the bottom part of Fig. 6 (left) leading to the martensitic transformation at the inner edge of the apex in the upper part of Fig. 6 (right). Hence, the model is able to handle true multiaxial loadings, and all tensor stress components (normal and shear components) are used to determine the characteristics of the martensitic transformation, i.e., amount of transformed material and direction of transformation. Also the influence of the included tension/compression asymmetry is visible in the upper part of Fig. 6 (right). Areas where the martensitic transformation is originated by tensile stress are slightly larger compared to the areas where the martensitic transformation is originated by compressive stress. A good agreement is also observed in the local appearance of martensite comparing FEA results and polarization microscope images shown in the lower part of Fig. 6 (right). Martensitic regions can be distinguished by their higher surface roughness in contrast to the regions where the material is still austenitic.

FEA result of the local stresses x-component σx (upper part) and y-component σy (lower part) at T = 22 °C under 400 µm tension and 400 µm compression (left). Polarization microscope images (grayscale, lower part) showing regions with detwinned martensite close to the apex of a diamond specimen and superimposed with the resulting localized martensite fractions from FEA using the MAS transformation law (upper part) at T = 22 °C under 400 µm tension and 400 µm compression (right)

Experimental and simulation results of tensile tests using the diamond specimen are shown in Fig. 7 for temperatures of T = 22 °C (left) and T = 37 °C (right). As mentioned earlier, one can clearly see that the use of the small strain tensor \(\underline{\varepsilon }_{{\left( {\widetilde{\varvec{u}}} \right)}}\) (dashed lines) leads to a distinction between experimental results and simulation, and thus the use of the Green strain tensor \(\underline{E}_{{\left( \varvec{u} \right)}}\) to account for large deformations is mandatory, especially if tensile displacement is applied to the diamond specimen. While FEA results show a slightly different behavior during the release of the load at T = 22 °C, the agreement with the experimental results at T = 37 °C is excellent, in particular for MAS transformation law. Therefore, we choose this transformation law to determine the mean strain and strain amplitude values for testing the fatigue behavior of the diamond specimen in the following, as shown in the next section.

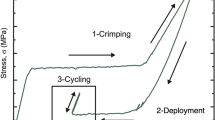

According to the experimental procedure, where diamond specimens are subject to cyclic oscillation after a compressive displacement, we performed FEA on these specimens in various minor loop scenarios. Figure 8 shows the total force as a function of the displacement for a mean displacement of 300 µm in compression and oscillations with displacement amplitudes of 50 µm (left, 100 µm peak-to-peak), 100 µm (middle, 200 µm peak-to-peak) and 150 µm (right, 300 µm peak-to-peak) at T = 37 °C. The experimental results and the FEA results are in good agreement. The oscillation frequency and thus the strain rate are limited in the experimental results by the tensile testing machine (v = 1 mm/s) and significantly lower in comparison with the fatigue setup. The shape of the minor loops is comparable and in good agreement with the FEA results with an oscillation frequency of 1 Hz. By using a higher oscillation frequency of 20 Hz, the slope in the minor loop is clearly increased for larger amplitudes due to the higher resulting strain rates. In compression, the maximum principal strain occurs typically close to the apex at the outer edges of the struts or at the inner edges close to the grip. The peak-to-peak values of these local maximum first principal strain during one period of the oscillation (f = 20 Hz) are finally used to determine the strain amplitude and the mean strain values. Here, a mean strain/strain amplitude of 2.70%/0.48% is determined for a displacement amplitude of 50 µm, 2.74%/1.29% for displacement amplitudes of 100 µm and 2.68%/1.79% for a displacement amplitude of 150 µm with a mean displacement of 300 µm, respectively.

Comparison of experimental (constant speed) and FEA results (constant frequency of 1 Hz and 20 Hz) using the MAS transformation low for diamond specimen under cyclic loading. The resulting force is shown as a function of displacement with a mean displacement of 300 µm in compression and displacement amplitudes of 50 µm (left), 100 µm (center) and 150 µm (right) at T = 37 °C

Results and Discussion

The fatigue data of the diamond specimen are plotted as constant life diagram with displacement amplitude as a function of mean displacement in Fig. 9 (left). A total number of 53 diamond specimen were tested with up to 420 µm mean displacement in compression and maximum displacement amplitudes of 250 µm. Therefore, 37 diamond specimen survived 107 pulsatile cycles (open squares) and 16 led to fracture before 107 pulsatile cycles where reached (solid squares). By using the above-described FEA implementation, the corresponding strain conditions are calculated in Fig. 9 (right) resulting in a maximum mean strain up to 4% and a maximum strain amplitude of 2.25%. For the sputtered Nitinol diamond specimen, an alternating strain limit of 1.75% is observed for compressive mean strains below 2.5%. Thus, the alternating strain limit is nearly twice as high compared to the strain limit of conventionally manufactured diamond specimen from standard Nitinol alloys (Ref 13). Furthermore, the strain limit of sputtered Nitinol diamond specimen is also slightly higher compared to the alternating strain limit of diamond specimen manufactured from optimized (limited size and abundance of inclusions) Nitinol alloys. Using commercially available Nitinol tubes of process-optimized (VIM + VAR) and high-purity (VAR) Nitinol alloys for the manufacturing process of the diamond specimen, an amplitude strain limit of 1.5% at 3% mean strain is reported (Ref 4). Inclusion size, area fraction and density which play a pivotal role for fatigue life (Ref 35), are significantly reduced for these optimized alloys, and thus the probability to nucleate a fatigue crack. This leads to lower fracture rates and a higher amplitude strain limit. It is therefore not surprising that the fatigue safety limit of sputtered Nitinol diamond specimen is on a comparable level due to the entire absence of detectable inclusions in sputtered Nitinol (Ref 36). Between 2.0 and 2.5% mean strain, the alternating strain limit drops from 1.5 to 0.8% at 3.5 to 4% mean strain for sputtered Nitinol diamond specimen. Here, the maximum local strain exceeds the end of the superelastic stress plateau of approximately 4% at 37 °C, as seen in Fig. 5 (right). Sputtered Nitinol has an isotropic grain orientation since cold or hot work processes that are used, e.g., for tube manufacturing are not required. In comparison, the larger superelastic stress plateau of 6% for diamond specimen from process-optimized and high-purity tubes might be the reason for these materials reaching test run out at a mean strain of 3%.

Constant life diagram of the diamond specimen fatigue data with displacement amplitude as a function of mean displacement (right) and resulting strain amplitude as a function of mean strain calculated using FEA (right). Open squares represent test conditions that survived 107 pulsatile cycles, and solid squares are those conditions that led to fracture at < 107 pulsatile cycles. Fracture tends to occur above the dashed line, representing the safety limit as a function of mean strain

Conclusion

We have developed an inexpensive fatigue test rig to perform high-cycle fatigue tests on a large number of Nitinol specimens, both in parallel and at different test parameters. The fatigue test rigs are used determine the fatigue safety limit of ultrapure Nitinol specimen fabricated using microsystem technology, i.e., magnetron sputter deposition. Mean strain and strain amplitudes for the particular diamond specimen are calculated using the FEA software Comsol Multiphysics. A multiaxial SMA material model was implemented with two different kinetic transformation laws, and simulation results show good agreement with the results from tensile tests. The determined fatigue behavior of sputtered Nitinol diamond specimen shows an excellent fatigue resistance with a high fatigue safety limit of 1.75% pulsatile strain amplitude for mean strains below 2.5%.

References

J. Mohd Jani, M. Leary, A. Subic, and M.A. Gibson, A Review of Shape Memory Alloy Research, Applications and Opportunities, Mater. Des., 2014, 56, p 1078–1113

N. Morgan, Medical Shape Memory Alloy Applications—The Market and Its Products, Mater. Sci. Eng., A, 2004, 378, p 16–23

T. Lottermoser et al., Magnetic Phase Control by an Electric Field, Nature, 2004, 430, p 541–545

S.W. Robertson et al., A Statistical Approach to Understand the Role of Inclusions on the Fatigue Resistance of Superelastic Nitinol Wire and Tubing, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater., 2015, 51, p 119–131

S.W. Robertson, A.R. Pelton, and R.O. Ritchie, Mechanical Fatigue and Fracture of Nitinol, Int. Mater. Rev., 2012, 57, p 1–37

G. Eggeler et al., On the Electropolishing of NiTi Braided Stents—Challenges and Solutions, Materwiss. Werksttech., 2014, 45, p 920–929

P.J.S. Buenconsejo, K. Ito, H.Y. Kim, and S. Miyazaki, High-Strength Superelastic Ti-Ni Microtubes Fabricated by Sputter Deposition, Acta Mater., 2008, 56, p 2063–2072

M.J. Mahtabi, N. Shamsaei, and M.R. Mitchell, Fatigue of Nitinol: The State-of-the-Art and Ongoing Challenges, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater., 2015, 50, p 228–254

M.J. Mahtabi, N. Shamsaei, and B. Rutherford, Mean Strain Effects on the Fatigue Behavior of Superelastic Nitinol Alloys: An Experimental Investigation, Procedia Eng., 2015, 133, p 646–654

M. Launey et al., Influence of Microstructural Purity on the Bending Fatigue Behavior of VAR-Melted Superelastic Nitinol, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater., 2014, 34, p 181–186

A.R. Pelton et al., Rotary-Bending Fatigue Characteristics of Medical-Grade Nitinol Wire, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater., 2013, 27, p 19–32

S. Miyazaki, K. Mizukoshi, T. Ueki, T. Sakuma, and Y. Liu, Fatigue life of Ti–50 at.% Ni and Ti–40Ni–10Cu (at.%) shape memory alloy wires, Mater. Sci. Eng., A, 1999, 273-275, p 658–663

A.R. Pelton et al., Fatigue and Durability of Nitinol Stents, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater., 2008, 1, p 153–164

R.L. De Miranda, C. Zamponi, and E. Quandt, Micropatterned Freestanding Superelastic TiNi Films, Adv. Eng. Mater., 2013, 15, p 66–69

C. Bechtold, R.L. de Miranda, and E. Quandt, Capability of Sputtered Micro-patterned NiTi Thick Films, Shape Mem. Superelasticity, 2015, 1, p 286–293

C. Chluba, C. Zamponi, R.L. de Miranda, C. Bechtold, and E. Quandt, Method for Fabricating Miniaturized NiTi Self-Expandable Thin Film Devices with Increased Radiopacity, Shape Mem. Superelasticity, 2016, 2, p 391–398

C. Bechtold, R.L. de Miranda, C. Chluba, and E. Quandt, Fabrication of Self-Expandable NiTi Thin Film Devices with Micro-Electrode Array for Bioelectric Sensing, Stimulation and Ablation, Biomed. Microdevices, 2016, 18, p 1–7

G. Siekmeyer, A. Schüßler, R.L. De Miranda, and E. Quandt, Comparison of the Fatigue Performance of Commercially Produced Nitinol Samples Versus Sputter-Deposited Nitinol, J. Mater. Eng. Perform., 2014, 23, p 2437–2445

C. Chluba et al., Ultralow-fatigue shape memory alloy films, Science, 2015, 348, p 1004–1007

C. Chluba et al., Effect of Crystallographic Compatibility and Grain Size on the Functional Fatigue of Sputtered TiNiCuCo Thin Films, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci., 2016, 374, p 20150311. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0311

Y. Liu, Z. Xie, J. Van Humbeeck, and L. Delaey, Asymmetry of Stress-Strain Curves Under Tension and Compression for NiTi Shape Memory Alloys, Acta Mater., 1998, 46, p 4325–4338

F. Thiebaud, M. Collet, E. Foltete, and C. Lexcellent, Implementation of a Multi-Axial Pseudoelastic Model to Predict the Dynamic Behavior of Shape Memory Alloys, Smart Mater. Struct., 2007, 16, p 935–947

F. Thiebaud, C. Lexcellent, M. Collet, and E. Foltete, Implementation of a Model Taking into Account the Asymmetry Between Tension and Compression, the Temperature Effects in a Finite Element Code for Shape Memory Alloys Structures Calculations, Comput. Mater. Sci., 2007, 41, p 208–221

L.C. Brinson, One-Dimensional Constitutive Behavior of Shape Memory Alloys: Thermomechanical Derivation with Non-constant Material Functions and Redefined Martensite Internal Variable, J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct., 1993, 4, p 229–242

J. Bonet and R.D. Wood, Nonlinear Continuum Mechanics for Finite Element Analysis, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2008

M. Brocca, L.C. Brinson, and Z.P. Bažant, Three-Dimensional Constitutive Model for Shape Memory Alloys Based on Microplane Model, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 2002, 50, p 1051–1077

O. Heintze and S. Seelecke, A Coupled Thermomechanical Model for Shape Memory Alloys-From Single Crystal to Polycrystal, Mater. Sci. Eng., A, 2008, 481–482, p 389–394

F. Richter, O. Kastner, and G. Eggeler, Implementation of the Müller-Achenbach-Seelecke Model for Shape Memory Alloys in ABAQUS, J. Mater. Eng. Perform., 2009, 18, p 626–630

F. Wendler, H. Ossmer, C. Chluba, E. Quandt, and M. Kohl, Mesoscale Simulation of Elastocaloric Cooling in SMA Films, Acta Mater., 2017, 136, p 105–117

J.E. Massad and R.C. Smith, A Homogenized Free Energy Model for Hysteresis in Thin-Film Shape Memory Alloys, Thin Solid Films, 2005, 489, p 266–290

S.J. Furst and S. Seelecke, Modeling and Experimental Characterization of the Stress, Strain, and Resistance of Shape Memory Alloy Actuator Wires with Controlled Power Input, J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct., 2012, 23, p 1233–1247

S.J. Furst, J.H. Crews, and S. Seelecke, Numerical and Experimental Analysis of Inhomogeneities in SMA Wires Induced by Thermal Boundary Conditions, Contin. Mech. Thermodyn., 2012, 24, p 485–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00161-012-0238-9

H. Ossmer et al., Evolution of Temperature Profiles in TiNi Films for Elastocaloric Cooling, Acta Mater., 2014, 81, p 9–20

A. Coda, M. Urbano, L. Fumagalli, and F. Butera, Investigation on the Hysteretic Behavior of NiTi Shape Memory Wires Actuated Under Quasi-Equilibrium and Dynamic Conditions, J. Mater. Eng. Perform., 2009, 18, p 725–728

M. Rahim et al., Impurity Levels and Fatigue Lives of Pseudoelastic NiTi Shape Memory Alloys, Acta Mater., 2013, 61, p 3667–3686

M. Wohlschlögel, R.L. de Miranda, A. Schüßler, and E. Quandt, Nitinol: Tubing Versus Sputtered Film—Microcleanliness and Corrosion Behavior, J. Biomed. Mater. Res.—Part B Appl. Biomater, 2016, 104, p 1176–1181

Acknowledgments

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) through the Research Training Group “Materials4Brain” (GRK 2154).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gugat, J.L., Bechtold, C., Chluba, C. et al. High-Cycle Mechanical Fatigue Performance of Sputtered Nitinol. J. of Materi Eng and Perform 29, 1892–1900 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-020-04668-2

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-020-04668-2