Abstract

Summary

This study examines factors associated with osteoporosis awareness and knowledge using Osteoporosis Prevention and Awareness Tool (OPAAT). Of 410 patients, majority of patients had a OPAAT score < 24 (n = 362, 88.3%). Lower education level (odds ratio (OR) (primary education): 3.63; OR (no formal education): 111.5; p < 0.001) and diabetic patients (OR: 1.67; p = 0.003) were associated with lower OPAAT scores.

Introduction

Lack of osteoporosis awareness forms a critical barrier to osteoporosis care and has been linked with increased institutionalization, healthcare expenditures, and decreased quality of life. This study aims to identify factors associated with osteoporosis awareness and knowledge among female Singaporeans.

Methodology

A cross-sectional study was conducted among adult female patients (aged 40 to 90 years old) who were admitted into Outram Community Hospital from April to October 2020. Osteoporosis awareness and knowledge were assessed using interviewer-administered Osteoporosis Prevention and Awareness Tool (OPAAT). High knowledge was defined as a OPAAT score ≥ 24. Multivariate logistical regression analyses were used to identify predictors of low OPAAT scores.

Results

Of 410 patients recruited, their mean age was 71.9 ± 9.5 years old and majority of patients had a OPAAT score < 24 (n = 362, 88.3%). Patients with lower OPAAT scores tended to be older (72.5 ± 9.2 vs 67.5 ± 10.1, p < 0.001), attained lower education level (p < 0.001), and were more likely to live in public housing (92.5% vs 81.5%, p = 0.009). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was higher in patients with low OPAAT scores (39.2% vs 18.8%, p = 0.006). After adjustment for covariates, lower education level (odds ratio (OR) (primary education): 3.63; OR (no formal education): 11.5; p < 0.05) and patients with diabetes mellitus (OR: 1.67; p = 0.03) were associated with lower OPAAT knowledge scores.

Conclusion

Elderly female patients in community hospital have inadequate osteoporosis awareness despite being at risk of fractures. There is a need to address the knowledge gap in osteoporosis, especially among diabetic patients or patients with lower education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is defined as a systemic skeletal condition that is characterized by low bone mass and progressive microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, which predisposes one to increased risk of fragile bones and fractures [1]. Globally, over 200 million women suffer from osteoporosis and it results in over 8.9 million fractures annually [2,3,4]. With the greying populations worldwide, the incidence of osteoporosis is expected to continue rising, alongside projected increases in hip fractures by 200–300% in the next 3 decades [2].

Asia is expected to contribute to 50% of the global tally of hip fractures by 2050 [5, 6]. Notably, Singapore has the highest reported incidence of hip fractures within Asia [5, 6]. The International Osteoporosis Foundation Asian Audit showed that one in three Singaporean women over 50 years old has osteoporosis [5]. Among females more than 60 years, half and one-quarter of the population were at intermediate and high risk of developing osteoporosis, respectively [7, 8]. Unsurprisingly, it has been estimated that the costs of managing hip fractures in Singapore will reach USD$145 million in 2050 [5, 6].

Despite its high prevalence, association with increased morbidity and mortality, osteoporosis remains under-diagnosed and under-treated [9]. Barriers which impede the delivery of optimal osteoporosis care and prevention include patient-, physician-, and healthcare system–related factors. Among patient-related factors, lack of public awareness of osteoporosis is regarded as the largest barrier to osteoporosis care, in the Asia–Pacific region [3, 10]. Importantly, higher levels of osteoporosis knowledge have been shown to correlate with greater utilization of osteoprotective practices such as exercise and calcium intake [11]. Furthermore, inadequate health literacy related to osteoporosis has been linked with higher rates of non-compliance to anti-osteoporosis treatment [12].

The levels affecting osteoporosis-related knowledge are known to vary across countries, study designs, and types of study participants recruited [13, 14]. For example, a study in Pakistan showed that only 8% of participants had a good level of osteoporosis knowledge [13, 14]. In contrast, a study conducted in China showed that the overall osteoporosis awareness was 67.8% [14]. In Singapore, the last household survey conducted 20 years ago showed that only half of females above 45 years were aware of osteoporosis[15] while a small pilot study among 56 female nurses showed that majority (94.6%) of them had good knowledge of osteoporosis and its risk factors [15]. More recently, a local primary care study showed that more than half of patients had low osteoporosis knowledge [16]. Pertaining to determinants of osteoporosis knowledge, there exist socio-demographic and cross-cultural differences similarly. For example, in the USA, patients who were of African or Asian ethnicity tended to have lower knowledge compared to their White counterparts [17]. Other factors which have been linked with better osteoporosis knowledge include higher education level, higher physical activity level, higher socio-economic status, prior BMD measurement, and osteoporosis treatment [10, 12, 15, 16, 18, 19].

With advances in medical care and increasing consumption of medical knowledge from non-traditional media, e.g., social media in the recent years, their impact on osteoporosis knowledge in the local population remains unclear. There is also paucity of data related to the levels of and unique factors associated with poor osteoporosis knowledge among female patients residing in community hospital. Hence, this study aims to evaluate the level of and factors associated with poor osteoporosis-related knowledge among females in community hospital. The findings from this study will enable healthcare administrators to better understand determinants of poor osteoporosis-related knowledge and facilitate the development of policies and programs to target patients with high risk of developing osteoporosis as well as patients residing in community hospitals.

Methodology

Study design and inclusion and exclusion criteria

A cross-sectional study was carried out among adult female patients (aged 40–90 years old) who were admitted to Outram Community Hospital (OCH) between April 2020 and October 2020. The lower limit of 40 years old was utilized as the study wanted to evaluate osteoporosis knowledge among younger female adults and that the onset of initial bone loss in osteoporosis starts in the fourth decade of life [20]. Outram Community Hospital is one of the three flagship community hospitals under the Singapore Health Services, the largest healthcare cluster in Singapore. It provides step-down medical services such as rehabilitative and sub-acute medical care for patients who are discharged from acute hospitals [21].

For inclusion in this study, eligible patients were required to have an Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT) score ≥ 7. Uncommunicative patients and patients with AMT score ≤ 6 were excluded (17). Consecutive sampling was utilized for patient recruitment. Informed consent from recruited patients. Singhealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) approval (CIRB Ref: 2020/2245) was obtained.

Osteoporosis Prevention and Awareness Tool (OPAAT)

The OPAAT is a 30-item instrument which assesses awareness and knowledge related to osteoporosis [22]. Items within the tool cover three key themes related to osteoporosis which are, namely, (1) osteoporosis in general; (2) consequences of untreated osteoporosis; and (3) osteoporosis prevention [22]. Each correct answer is awarded 1 point with a maximum score of 30. An OPAAT score of 24 or greater is defined as high osteoporosis-related knowledge, as per the developer of the tool. The English and Malay versions of the tool have been validated for use [22].

As a significant proportion of the study population were expected to speak only Mandarin, the OPAAT was translated into Chinese language via forward-translations and back-translations. This was performed by a native Chinese healthcare professional who was bilingual in English and Chinese. Another independent bilingual healthcare professional assisted in identifying and resolving inadequate expressions or discrepancies of the translation. Thereafter, another independent translator whose mother tongue is English and had no knowledge of the questionnaire was tasked to perform the back-translation to English. Pre-testing and cognitive interviewing with 10 female patients were conducted before finalizing the translated version.

Socio-demographic and clinical variables collected

A separate standardized questionnaire was used to collect data related to the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients. Socio-demographic data such as age, marital status, ethnicity, educational level, and employment status were collected. For clinical variables, information such as patient’s history of fragility fracture, bone mineral density (BMD) measurement, and medical conditions were extracted. OSTA score and FRAX score of the patients were computed to assess patients’ risk of osteoporosis and fractures. Lastly, details related to participants’ source of osteoporosis knowledge and preferred mode of bone health education were collected.

Sample size computation

Using estimates from a study by Saw et al. which showed that 58% of female Singapore citizens were aware of osteoporosis and factoring 10% of patients with incomplete data, 410 patients was the minimum number of patients required, after applying the Cochran formula [n = (Z0.95)2 P[(1 − P)/D2].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the study population. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation or number (percentage). To evaluate differences in the characteristics of patients with low and high OPAAT scores, Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables while chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. To identify factors associated with OPAAT knowledge scores, multivariate logistical regression was performed. Socio-economic which included patients’ age, working status, education level, housing type, smoking status, alcohol status, preferred speaking and reading languages, and clinical comorbidities were entered in the regression model, after checking for collinearity and interactions. All statistical analyses were performed using the STATA software, Version 16.0 (STATA corporation, College Station, Texas). A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Table 1 shows the baseline socio-demographic characteristics of patients. The mean age of patients was 71.9 ± 9.5 and majority of patients were of Chinese ethnicity (n = 354, 96.3%). Most of the patients stayed in public housing (n = 374, 97.2%) and received primary to secondary education (n = 268, 65.4%).

With regard to the clinical characteristics of patients (Table 2), majority of the study population did not have a prior diagnosis of osteoporosis (n = 304, 74.2%). Among 106 patients with known osteoporosis (25.8%), about 73.6% of them (n = 78) received osteoporosis treatment. Approximately one-third of patients (36.8%) had diabetes while only 2.2% of patients had rheumatoid arthritis.

Characteristics of patients with low and high OPAAT scores

Within the study population, most patients had low OPAAT scores (n = 362, 88.3%) while 48 patients had high knowledge scores.

Patients with low OPAAT scores tended to be older (72.5 ± 9.2 vs 67.5 ± 10.1, p < 0.001), attained lower education qualifications (p < 0.001), and were more likely to live in public housing (92.5% vs 81.5%, p = 0.009) (Table 1). With regard to spoken and reading language, a larger proportion of patients with low OPAAT scores spoke Chinese dialects (42% vs 14.6%, p < 0.001) and were illiterate (26.0% vs 0%, p < 0.001) (Table 1).

With regard to their clinical characteristics, the proportion of patients with known osteoporosis or patients on anti-osteoporotic treatment were comparable (p > 0.05) although more patients had diabetes mellitus (39.2% vs 18.8%, p = 0.006). Patients were more likely to have FRAX score for risk of hip fractures ≥ 3% (64.6% vs 45.8%, p = 0.011), and FRAX score of ≥ 20% for major osteoporotic fractures (35.9% vs 18.8%, p = 0.018). Importantly, more patients with low OPAAT scores presented with fragility fractures (26.0% vs 12.5%, p = 0.035).

Multivariate analysis for predictors of low OPAAT knowledge scores

Table 3 shows the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis for predictors of low OPAAT scores. After adjustment for covariates, lower education level (odds ratio (OR) (primary vs tertiary education): 3.63, p = 0.003; OR (no formal education vs tertiary education): 11.5; p < 0.001) and having diabetes mellitus (OR: 1.67; p = 0.03) were predictive of low OPAAT scores.

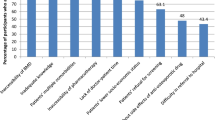

Sources and preferred sources of osteoporosis knowledge

Table 4 shows the sources and preferred sources of patients recruited within the study. The top three sources of osteoporosis-related knowledge were television/radio (34.9%), healthcare professionals (30.7%), and newspaper/other reading materials (30.0%). For the preferred sources of knowledge, majority of patients preferred healthcare professionals (64.2%), television/radio (32.2%), and newspaper/other reading materials (26.6%).

Patients with lower OPAAT scores were less likely to receive osteoporotic knowledge from healthcare talks (4.4% vs 12.5%, p = 0.020), newspaper/other reading materials (24.9% vs 68.8%), and internet (4.4% vs 25%, p < 0.001). However, a greater proportion of them preferred to received osteoporosis-related knowledge from healthcare professionals (66.9% vs 43.8%, p = 0.002), healthcare talks (8.3% vs 2.1%, p = 0.006), and family/friends/colleagues (10.2% vs 0%, p = 0.020). They were less likely to prefer newspaper or other readings materials as sources of osteoporosis knowledge (22.7% vs 56.3%, p < 0.001).

Discussion

To our best knowledge, this is the first Asian study which has evaluated osteoporosis knowledge among patients residing in community hospital. Overall, this study showed that the prevalence of low osteoporosis awareness and knowledge among elderly females in community hospital was high. Of note, the two main risk factors associated with low osteoporosis-related knowledge included lower education levels and having diabetes.

Compared to other countries such as China (67.8%) and Malaysia (87.1%), the proportion of female patients with good osteoporosis knowledge in this study was low (11.7%) [11, 14]. This was also markedly lower than the previous local study performed 2 decades ago which showed that 57.3% had good osteoporosis awareness. Potential explanations for differences in study findings could be related to the study population and type of instruments used for assessment of osteoporosis-related knowledge. Currently, there exists a multitude of instruments available to assess osteoporosis-related knowledge such as the Osteoporosis Knowledge Assessment Tool (OKAT) and Osteoporosis Questionnaire (OPQ) [23, 24]. Majority of these existing tools focused on themes related to osteoporosis treatment while the OPAAT questionnaire focuses on knowledge related to osteoporosis prevention [22]. Given the large number of items in these questionnaires which require significant amount of time to complete, there is a need for the development of an abbreviated, standardized instrument which assesses both osteoporosis prevention and treatment to facilitate quicker and more holistic assessment of osteoporosis-related knowledge.

Diabetes mellitus was shown to be associated with low osteoporosis knowledge in our study. This was similar to a study conducted in Malaysia among diabetes patients which found that only one-third of patients had high osteoporosis knowledge. Likewise, other studies performed in Pakistan and Palestine showed that majority of diabetes patients had poor osteoporosis-related knowledge [25, 26]. A potential mediating factor for diabetes mellitus and its relationship with poor osteoporosis knowledge could be due to higher prevalence of low health literacy among diabetic patients [27]. Poor health literacy has been consistently linked with poor health outcomes, lack of awareness on medical conditions, and lower uptake of preventive health behaviors and services [27]. In particular, low health literacy has also been linked with poorer glycemic control in diabetic patients [28]. With the ongoing diabetes epidemic, our study findings highlight the importance of targeting this group of patients for osteoporosis education, so as to improve their knowledge on the subject.

In this study, lower education was predictive of poorer osteoporosis-related knowledge. Similar findings have been reported in other countries where higher education levels were consistently associated with greater osteoporosis awareness and knowledge [1, 11, 16, 18, 25]. While higher osteoporosis-related knowledge is generally associated with better clinical outcomes, a study in Iran showed that more highly educated patients with greater osteoporosis knowledge often fail to utilize their knowledge to adopt osteo-preventive practices such as exercise and having adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D [25, 29]. While our study did not explore the correlation between osteoporosis knowledge and adoption of preventive strategies for osteoporosis, the study by Etemadifar MR et al. suggests that there is a potential role in educating patients with high osteoporosis knowledge on prevention of osteoporosis [29]. For patients that are less well educated, osteoporosis educational programs should be tailored to patients’ literacy levels to improve their awareness of osteoporosis.

With regard to age, it did not correlate with levels of osteoporosis knowledge in this study. This concurred with findings from two studies performed in the USA and Canada[30], but differed from a multi-center study in Turkey which showed an inverse relationship between age and level of osteoporosis awareness [31]. A potential reason for the differences could be due to the cognitive function of study participants as patients with moderate and severe cognitive impairment were excluded in this study. Cognitive function of patients plays an important role in one’s ability to evaluate and assimilate health-related knowledge and has been postulated to contribute to the variation in osteoporosis knowledge among elderly patients [32]. This was demonstrated in a study evaluating the effectiveness of an osteoporosis education program which showed that a positive correlation between increments in osteoporosis knowledge pre- and post-intervention with cognition [33]. Another potential reason could be due to the reduced effect of age among elderly patients as majority of patients in this study were above 65 years old, similar to the age profile of female patients admitted into Singapore community hospitals [34].

With regard to sources of osteoporosis-related knowledge, this study showed that healthcare professionals and television/radio were most preferred sources by patients. In addition, majority of patients indicated support for osteoporosis education in community hospital. Given that community hospitals serve as an important port-of-call for elderly patients who require intensive rehabilitation and these patients are often at high-risk for osteoporosis, healthcare policymakers may wish consider the introduction of osteoporosis education programs for these patients during their hospitalization. A study in Korea has shown that a multi-faceted osteoporosis education program comprising of summary of osteoporosis and its risk factors, nutritional education and an exercise presentation was able to improve patients’ osteoporosis knowledge and reduce their risk of osteoporosis [35]. Similar programs may be adapted for use in community hospitals locally.

Findings from this study should be interpreted with the following limitations. Due to the single-center nature of the study, the study results may not be representative of all community hospitals in Singapore. Future studies should consider the recruitment of patients in other community hospitals to increase the generalizability of results. Additionally, the coronavirus 2019 pandemic had affected proportions of post-elective procedure admissions in one of the months of study recruitment. In response to COVID-19 circuit breaker measures, elective procedures were deferred in the month of April 2020 [36]. While recall bias was expected in this study, this was minimized by the screening of patients with potential cognitive issues by the AMT prior to patient recruitment and careful selection of administered questions. Furthermore, while the study sample is adequately powered for statistical analyses, the overall sample size was relatively small and only a small proportion of patients where below 50 years old (2.1%). With the availability of administrative databases with more patient information, larger studies should be performed in the future to allow for more detailed evaluation of osteoporosis knowledge including younger female adults. Another limitation of this study was the heterogeneity of the study population. Majority of patients were not formally with osteoporosis while most patients with osteoporosis were on anti-osteoporotic treatment. Future studies should consider performing case–control studies involving patients who suffered from fragility fractures and matched controls without fragility fractures in the community. This will facilitate the healthcare administrators to identify important osteoporosis-related knowledge gaps and aid in formulating secondary and tertiary osteoporosis prevention policies. Lastly, factors such as gender, level of physical activities, dietary consumption of calcium, and distance to community facilities which could affect osteoporosis knowledge and awareness were not studied. Future studies should consider evaluating the role of these factors in levels of osteoporosis knowledge among patients.

Conclusions

Overall, our study showed that females community hospital patients in Singapore had suboptimal knowledge related to osteoporosis, despite being at high risk of osteoporotic fractures. Important risk factors associated with lower osteoporosis-related knowledge and awareness include lower education qualifications and having T2DM. Given that low osteoporosis-related knowledge has been associated with poor clinical outcomes such as increased risk of fractures and prolonged institutionalization, greater efforts should be directed to educate these at-risk patients to improve their awareness of osteoporosis. The design of educational materials and programs should take into account patients’ preferences for such knowledge which may include the use of traditional media such as newspaper, radio, and television as well as knowledge sharing by healthcare professionals.

References

Compston J et al (2017) UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):43

Khan AZ, Rames RD, Miller AN (2018) Clinical management of osteoporotic fractures. Curr Osteoporos Rep 16(3):299–311

World Health Organisation, WHO scientific group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. World Health Organisation: Belgium.

Yeam CT et al (2018) A systematic review of factors affecting medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 29(12):2623–2637

International Osteoporosis Foundation, The Asia-Pacific regional audit: epidemiology, costs & burden of osteoporosis in 2013. 2013: Switzerland.

Chan DD et al (2018) Consensus on best practice standards for Fracture Liaison Service in the Asia-Pacific region. Arch Osteoporos 13(1):59

Wang P et al (2019) Estimation of prevalence of osteoporosis using OSTA and its correlation with sociodemographic factors, disability and comorbidities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(13):2338

Pouresmaeili F et al (2018) A comprehensive overview on osteoporosis and its risk factors. Ther Clin Risk Manag 14:2029–2049

Chau YT et al (2020) Undertreatment of osteoporosis following hip fracture: a retrospective, observational study in Singapore. Arch Osteoporos 15(1):141

Merle B et al (2019) Osteoporosis prevention: where are the barriers to improvement in French general practitioners? A qualitative study. PloS one 14(7):e0219681–e0219681

Chan, C.Y., et al., Levels of knowledge, beliefs, and practices regarding osteoporosis and the associations with bone mineral density among populations more than 40 years old in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019. 16(21).

Roh YH et al (2017) Effect of health literacy on adherence to osteoporosis treatment among patients with distal radius fracture. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):42

des Bordes J et al (2020) Knowledge, beliefs, and concerns about bone health from a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. PLOS ONE 15(1):e0227765

Oumer KS et al (2020) Awareness of osteoporosis among 368 residents in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21(1):197

Saw SM et al (2003) Awareness and health beliefs of women towards osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 14(7):595–601

Lulla D et al (2021) Assessing the knowledge, attitude and practice of osteoporosis among Singaporean women aged 65 years and above at two SingHealth polyclinics. Singapore Med J 62(4):190–194

Nam H-S et al (2013) Racial/ethnic differences in bone mineral density among older women. J Bone Miner Metab 31(2):190–198

Díaz-Correa LM et al (2014) Osteoporosis knowledge in patients with a first fragility fracture in Puerto Rico. Bol Asoc Med P R 106(1):6–10

Rotondi NK et al (2018) Identifying and addressing barriers to osteoporosis treatment associated with improved outcomes: an observational cohort study. J Rheumatol 45(11):1594–1601

Orthoinfo. Healthy bones at every age. 2012 [cited 2021 17 July]; Available from: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/staying-healthy/healthy-bones-at-every-age/.

Ministry of Health Singapore, Community hospital care. 2017: Singapore.

Toh LS et al (2015) The development and validation of the Osteoporosis Prevention and Awareness Tool (OPAAT) in Malaysia. PLOS ONE 10(5):e0124553

Winzenberg TM et al (2003) The design of a valid and reliable questionnaire to measure osteoporosis knowledge in women: the Osteoporosis Knowledge Assessment Tool (OKAT). BMC Musculoskelet Disord 4:17–17

Pande KC et al (2000) Development of a questionnaire (OPQ) to assess patient’s knowledge about osteoporosis. Maturitas 37(2):75–81

Abdulameer SA et al (2019) A comprehensive view of knowledge and osteoporosis status among type 2 diabetes mellitus in Malaysia: a cross sectional study. Pharm Pract 17(4):1636–1636

Ishtaya GA et al (2018) Osteoporosis knowledge and beliefs in diabetic patients: a cross sectional study from Palestine. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 19(1):43

Berkman ND et al (2011) Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 155(2):97–107

Protheroe J et al (2017) Health literacy, diabetes prevention, and self-management. J Diabetes Res 2017:1298315–1298315

Etemadifar MR et al (2013) Relationship of knowledge about osteoporosis with education level and life habits. World J Orthop 4(3):139–143

Wang L et al (2016) A model of health education and management for osteoporosis prevention. Exp Ther Med 12(6):3797–3805

Kutsal YG et al (2005) Awareness of osteoporotic patients. Osteoporos Int 16(2):128–133

Shin H-Y et al (2014) Association between the awareness of osteoporosis and the quality of care for bone health among Korean women with osteoporosis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15:334–334

Abrahamson SJ, Khan F (2006) Brief osteoporosis education in an inpatient rehabilitation setting improves knowledge of osteoporosis in elderly patients with low-trauma fractures. Int J Rehabil Res 29(1):61–64

Ministry of Health Singapore. Admissions and outpatient attendances. 2021 [cited 2021 July 2021]; Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/singapore-health-facts/admissions-and-outpatient-attendances.

Jo WS et al (2018) The impact of educational interventions on osteoporosis knowledge among Korean osteoporosis patients. Journal of bone metabolism 25(2):115–121

Teo, J., Coronavirus: hospitals in Singapore may resume elective procedures in gradual manner, in The Straits Times. 2021: Singapore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Huey Chieng Tan and Jun Jie Benjamin Seng are co-first authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, H.C., Seng, J.J.B. & Low, L.L. Osteoporosis awareness among patients in Singapore (OASIS)—a community hospital perspective. Arch Osteoporos 16, 151 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-01012-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-021-01012-6