Abstract

A recent increase in research on social entrepreneurship (SEship) has been characterized by more focus on gender-based topics, especially women. To address the status of women in SEship, we conduct a rigorous systematic literature review of 1142 papers on SEship and 59 articles on the sub-domain of women. Based on the findings, the article presents several suggestions for future research: (i) reinterpretation of theoretical concepts, (ii) social integration and overcoming gender discrimination, (iii) expansion of sectors and regions, and (iv) operation strategy and performance factors. This study contributes to the development of SEship by providing an overview of women in SEship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social entrepreneurship (hereafter, SEship) is defined as an “entrepreneurial activity with an embedded social purpose” (Austin et al. 2006). In recent decades, it has evolved as a significant research domain for firms and academics (Kannampuzha and Hockerts 2019; Kim 2022; Rey-Martí et al. 2016), and the number of studies and publications on this topic have steadily increased (Hota et al. 2020; McQuilten 2017; Short et al. 2009; Zahra et al. 2014). The growth in research covers topics such as the social impact of SEship (Nguyen et al. 2015), social innovation and SEship (Phillips et al. 2015), SEship business strategies and business models (George and Reed 2016; Roy and Karna 2015), comparisons with business-oriented entrepreneurship (Simón-Moya et al. 2012), and value creation and dissemination by SEship (Brandsen and Karré 2011; Nega and Schneider 2014; Sulphey and Alkahtani 2017).

Women, representing the fastest-growing category of entrepreneurship, are receiving attention from scholars as important organizational members and beneficiaries (Anggadwita et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2019; Hechavarría et al. 2017; Lee and Jung 2015; Tripathy et al. 2022; Yang et al. 2020). This phenomenon provides the opportunity to review and reflect on how the field of SEship will progress. Since discussions on women in SEship can contribute to expanding the entrepreneurship field and the diversity of gender studies (Calás et al. 2009; Rosca et al. 2020), it is important to synthesize these discussions collectively. Thus, the existing literature must be collated and reflected upon to identify new directions and future challenges. However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no thorough literature review study on women in SEship compared to overall SEship using a rigorous systematic literature review method.

As for conducting such a literature review, the researchers took two perspectives: the popularity-based approach and the network-based approach (Choi et al. 2011; Fahimnia et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2018; Park and Jeong 2019; Gupta et al. 2020; Hota et al. 2020; Tan et al. 2020). However, the popularity-based approach, also known as bibliometric analysis, is recognized as unsuitable for identifying shared topical issues within a given research field despite offering significant insight into a given field by examining the usage frequency in published papers (Choi et al. 2011; Park and Jeong 2019). In contrast, the network-based approach, which includes citation and co-citation analysis, explores the significant and commonly shared topical issues among published papers in a given field. However, the network-based approach does not create a further specified knowledge network within a given research area (Choi et al. 2011; Park and Jeong 2019).

To address the perceived drawbacks in the extant literature and achieve a more comprehensive research evaluation on this topic, this study conducted a systematic literature review by combining the traditional systematic literature review approach (bibliometric, citation, and co-citation analysis) with keyword network analysis. Keyword network analysis is an effective method for examining the research trends of specific issues in a given field by constructing a keyword network based on nodes (author’s keywords) and links (the occurrence of the author’s keywords in other papers). However, in SEship, few literature review studies have adopted keyword network analysis to discover overall trends and issues. Thus, we attempt to achieve the following three objectives in this study by applying a keyword network analysis to achieve a more rigorous systematic literature review:

-

1.

Identify influential issues and topics that significantly contribute to the study of women in SEship field;

-

2.

Understand the evolution of women in SEship by identifying linkages among core papers and the evolution of these linkages over time;

-

3.

Identify the status of women in SEship research and discover future directions and challenges by comparing this to overall SEship research.

By addressing the above-stated research objectives, we mainly contribute to the development of women in SEship field in three ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first research of its type to comprehensively examine the literature on women in SEship within overall SEship by combining traditional systematic approaches with keyword network analysis. Second, we contribute to understanding an overview of women in SEship within the overall SEship field by identifying main issues, emerging issues, and key topics. Third, we suggest research gaps and outline important research directions and considerations for future women in SEship field.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the research background by reviewing systematic literature on women in SEship. Section 3 describes the applied methodologies (bibliometric and network analysis) for a rigorous systematic literature review on women in SEship. Then, we exhibit the results of the bibliometric and network analyses using Netminer, as a network analysis software tool, in Sects. 4 and 5, respectively. In Sect. 6, we discuss research gaps and future research opportunities. Lastly, in Sect. 7, we conclude our research by providing the implications and contributions along with the limitations.

2 Previous systematic literature reviews of women in SEship

According to emerging literature, women are making significant contributions to entrepreneurial activities (Noguera et al. 2013) and economic development (Hechavarría et al. 2019; Kelley et al. 2017) in terms of creating new jobs and increasing gross domestic product (GDP) (Ayogu and Agu 2015; Bahmani-Oskooee et al. 2012). Women also positively impact reducing poverty and social exclusion (Langowitz and Minniti 2007; Rae 2015). Furthermore, women, as important accelerators, have an important role in gender in promoting social entrepreneurial intentions (Cardella et al. 2021). There are an ever-growing number of articles related to women in SEship (Lortie et al. 2017; Rosca et al. 2020; Sahrakorpi and Bandi 2021), providing opportunities to reflect on how to advance the field. However, despite the growing number of studies on women in SEship, there are a lack of sufficient research regarding female social entrepreneurs as strategy adopters to solve social problems (Rosca et al. 2020). Thus, the existing literature must be synthesized and analyzed to identify new directions and challenges.

Despite the growing importance of women in SEship, the status of women’s research within SEship remains unclear. Although existing studies on women in SEship have contributed significantly to our understanding of it, little is known about how the field of research is evolving, which management areas are being addressed, which issues have influenced these given areas, and what the relationships are among the main topics. Therefore, to identify potential research gaps and develop new ideas and theories that serve as a basis for future research, we must map and evaluate the current body of research on women in SEship.

Researchers have adopted two perspectives in conducting literature reviews on women in SEship. One perspective is the popularity-based approach, which uses bibliometric analysis (Choi et al. 2011). The popularity-based approach’s bibliometric analysis offers insights not captured or evaluated by other reviews using authors, their affiliation, popular words used in titles and abstracts, and author keywords (Choi et al. 2011; Fahimnia et al. 2015; Gupta et al. 2020; Tan et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2018). The popularity-based approach indicates the significance of words or keywords in a given discipline by examining their frequency of use in published papers. However, this method is unsuitable for associating shared topical issues within a given research field because it is unable to identify relationships among published articles (Choi et al. 2011; Park and Jeong 2019).

Another approach is the network-based approach, which conducts network analyses such as citation and co-citation analysis using citations generated from papers (Choi et al. 2011; Fahimnia et al. 2015; Hota et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2018). Citation analysis is implemented to explore influential issues by counting how frequently an article is cited by other articles (Fahimnia et al. 2015; Park and Jeong 2019; Hota et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2018). Co-citation analysis identifies commonly shared topical issues within a given field through a co-citation network comprising a set of papers as nodes and their co-occurrences in other papers as links (Hota et al. 2020; Leydesdorff 2011; Radicchi et al. 2004). However, these network analyses have mainly focused on published articles rather than specified author keywords (Park and Jeong 2019). Therefore, from a comprehensive perspective, a network commonly adopted for citations or co-citation analyses does not directly derive a further specified knowledge network within a given research area (Choi et al. 2011; Park and Jeong 2019). To comprehensively identify topics on women in SEship, we must include specific keywords not involved in the citation and co-citation network (Park and Jeong 2019). Therefore, to address this, we implement a rigorous systematic literature review that includes specified author keywords through traditional systematic literature review approaches (bibliometric, citation, and co-citation analysis).

Furthermore, as no literature review has been conducted on this topic, it is not known how research on women in SEship has developed and is being implemented.

3 Research methodology

We conducted a systematic literature review on women in SEship by combining traditional systematic approaches with keyword network analysis. First, we selected social entrepreneurship-related journals from the SCOPUS database. We used “social entrepre*,” “social enterpri*,” “social venture,” and “social business” as the primary search keywords based on previous studies on SEship (Hota et al. 2020; Saebi et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2020). Only articles written in journals with a 1.0 impact factor or greater were used to select the most influential papers. Despite the importance of providing valuable and insightful managerial guidance to women social entrepreneurs in the business environment (Rosca et al. 2020), it remains unclear how women entrepreneurs navigate. Thus, we used only business administration journal articles written in English and excluded conference papers, book series, commercial publications, and magazine articles. Therefore, the initial search attempts resulted in 1142 papers published from 1972 to 2021 (searched in December 2021). As this study is explicitly addressing the status of women in SEship field, we further collected 59 papers on this topic from the 1142 articles using search keywords, such as “female,” “woman,” and “women.”

This study attempts to achieve the following objectives. First, what is the current status of research on women in SEship? Second, what is the most influential paper among studies on women in SEship? Third, how does research on women in SEship change over time? To identify those questions, first, we adopted bibliometric analysis to provide insights on items, such as author, journal, and publication statistics. Second, we conducted a citation analysis to identify the most influential papers to analyze the status of overall SEship and women in SEship. Third, we performed a co-citation analysis to identify commonly shared topics through the co-occurrence of two given articles in other papers. A dynamic co-citation analysis was conducted to understand the evolution of overall SEship and women in SEship over time. Finally, to address the perceived drawbacks of a systematic literature review that uses only traditional approaches (bibliometric, citation, and co-citation analysis), we performed a keyword network analysis to represent the complete “intellectual structure” or “knowledge base” of the SEship field. Additionally, we addressed the specific changes in critical keywords over time using NetMiner as a network analysis tool. NetMiner has excellent functionality for network analysis (Huisman et al. 2005). Thus, for a more rigorous network analysis, we selected NetMiner to conduct our research. Figure 1 shows the process of the systematic literature review analysis.

4 Bibliometric analysis

A bibliometric analysis examines data statistics, including authors, affiliations, titles, abstracts, and author keywords (Fahimnia et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2018). Thus, a bibliometric analysis can provide insight into new perspectives for future direction by identifying the existing state of a given discipline (Hashemi et al. 2022). This paper conducted a bibliometric analysis to identify the current status of research on SEship and women in SEship by mainly focusing on authors, journals, and publication year.

4.1 Influential authors of SEship and women in SEship

To understand the status of SEship and women in SEship, scholars interested in conducting SEship research must identify influential researchers. Therefore, we extracted the top contributing authors by the number of papers they authored or co-authored. Table 1 represents the top contributing authors based on the number of published papers.

4.2 Publication statistics

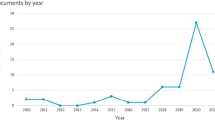

We investigated publication statistics to identify the trend of SEship in the number of papers published. As shown in Fig. 2, the field of overall SEship is still in its growth and expansion period, while the area of women in SEship is in relatively early stages. The number of published papers on overall SEship increased from 15 in 2009 to 134 in 2021, representing geometric growth in publications. These findings emphasize that researchers and practitioners recognize the importance of SEship as a vital knowledge discipline in business management. In contrast, the number of publications on women in SEship has remained the same yearly from 2009 to 2021; thus, there has been no noticeable growth in publications on women in SEship.

Furthermore, 187 journals have contributed to the publication of 1142 papers on overall SEship, but only 33 of the 187 journals have contributed to the publication of 59 papers on women in SEship. Papers on women in SEship comprise only 5% of all articles published on SEship. Also, it is the top ten journals that have published these articles, representing approximately 41% of all papers published on overall SEship and 54% of women in SEship, respectively. Tables 2 and 3 show the journal in which these papers appeared. It was noticeable that “Journal of Business Ethics” covered a wide variety of topics, ranging from overall SEship to women in SEship. On the other hand, “Journal of Business Research,” “Journal of Cleaner Production,” “Technological Forecasting and Social Change,” “Journal of Management Decision,” and “International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal,” among the top journals that contain overall SEship studies, does not cover the subject of women.

5 Network analysis

5.1 Citation analysis

Citation analysis can objectively identify prominent academic articles through their popularity and significance by establishing how frequently they have been cited in other articles (Fahimnia et al. 2015; Hota et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2018). For a rigorous citation analysis, we first constructed a local citation network that determined the citation frequency of a published paper in any of the selected 1121 other published articles. Then, PageRank, which measures “prestige” using the number of times a document has been cited, was used on papers that discuss the main issues (Brin and Page 1998; Fahimnia et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2018). Table 4 presents the top ten papers on overall SEship and women in SEship by PageRank measures.

The PageRank score of a paper in a local citation network comprised N papers, where N papers (i.e., \({T}_{1}\), …, \({T}_{n}\)) cite paper A and parameter d is a damping factor describing the fraction of random walks that continue to spread along with the citations. Following the original Google PageRank of Brin and Page (1998), we set the parameter d to be 0.85, and consider paper A (that other papers have cited, namely, \({T}_{1}\), …, \({T}_{n}\)) where paper \({T}_{i}\) has citations C(\({T}_{i}\)). Here, the PageRank of paper A (denoted by PR(A)) in a local network of N papers can be measured as follows:

As shown in Table 4, the top ten papers on overall SEship show that the topics mainly addressed are the definitions and concepts of SEship and social enterprise from various perspectives. For example, to establish the definition of SEship, Peredo and McLean (2006) distinguished between “social” and “entrepreneurship,” and Austin et al. (2006) conducted a comparative analysis between SEship and “commercial entrepreneurship.” Among the top ten papers on women in SEship, the issues primarily addressed were empowerment through SEship and the advantages of gender differences in women’s social inclusion. For example, Datta and Gailey (2012) represented that SEship enhances women’s competence through empowerment. Haugh and Talwar (2016) indicated SEship as a process of empowering women to change social norms. Comparing the trends of both streams, we determined that the study of overall SEship has evolved around conceptual papers discussing the definition and components of SEship and social enterprise. In contrast, on this conceptual basis, phenomena such as the social integration of women and the pursuit of the social purpose of female entrepreneurs have been empirically identified.

5.2 Co-citation analysis

A co-citation network consists of a set of nodes (papers) and links (the co-occurrence of the papers in other papers) (Leydesdorff 2011; Radicchi et al. 2004). This method implies that the more often two articles are cited together, the closer their relationship is. Hence, frequently cited papers are more likely to present similar subject areas (Hjørland 2013) and be considered part of the same research field (Culnan and Markus 1987). Thus, a co-citation analysis was conducted to identify prevalent topics in each field (Fahimnia et al. 2015; Hota et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2018).

In the co-citation analysis, we divided a local citation network of papers into “clusters” where the density of links is greater between the identical cluster articles than in other clusters (Clauset et al. 2004; Leydesdorff 2011; Radicchi et al. 2004). Xu et al. (2018) state that “The modularity index of a partition is a scalar value between − 1 and + 1 that measures the density of links inside communities versus the links between communities” (2018, p.164). According to Blondel et al. (2008), the modularity index \(Q\) can be calculated for a weighted network as follows:

where \({A}_{ij}\) represents the weight of the link between nodes i and j, \({k}_{i}\) is the sum of the weights of the links attached to node i (\({k}_{i}=\sum_{j}{A}_{ij}\)), \({c}_{i}\) is the community to which node i is assigned, \(\delta\) (\(u, \nu\)) equals 1 if \(u\) = \(\nu\) and equals 0, otherwise, and finally\(m= \frac{1}{2}\sum_{ij}{A}_{ij}\).

In Table 5, the research on overall SEship is divided into six topical clusters by applying co-citation analysis. In Table 6, the study on women in SEship is categorized into three clusters by co-citation analysis. Furthermore, to identify the significant topical issues of each cluster, we conducted content analysis on core papers selected using PageRank measures.

According to the research on overall SEship in Table 5, Cluster 1 corresponded to the topic of identifying the unique characteristics of SEship through comparison. For example, Austin et al. (2006) compared social and commercial entrepreneurship. Dacin et al. (2010) contrasted SEship with other forms of entrepreneurship and explored its unique features.

Cluster 2 focused primarily on the regional characteristics of social purpose organizations. For example, Kerlin (2006) compared American and European social enterprises and conducted discussions with social enterprise scholars on both sides of the Atlantic. Thomas (2004) studied how a new social enterprise model—the social cooperative—has become instrumental in expanding the social economy in the Italian context. Kerlin (2010) compared the different factors shaping social enterprise across seven regions and countries.

Cluster 3 included theorization and conceptualization of SEship. For example, Mair and Martí (2006) identified and elaborated on the essential components of SEship. Dacin et al. (2011) also examined the conceptual definition of SEship and future research questions. Bacq and Janssen (2011) reviewed definitional issues associated with SEship based on geographical and thematic criteria.

Cluster 4 mainly contained papers corresponding to the emergence and evolution of SEship and social purpose organizations. For example, Dees (1998) presented a social enterprise spectrum to help nonprofit leaders understand and assess the potential and risks of commercialization. Meanwhile, Dart (2004) explained the emergence and evolution of social enterprise using institutional theories of organization. Chell (2007) discussed social enterprise and whether it might be interpreted as a form of entrepreneurship.

Cluster 5 corresponded to the development and growth of SEship. For example, Nicholls (2010) explained the development of SEship in terms of its key actors, discourses, and narrative logic. Prabhu (1999) examined social entrepreneurial leadership behavior and organizations’ growth and survival compared to mainstream entrepreneurship research. Tracey and Jarvis (2007) studied how the different types of SEship and their varying degrees of embeddedness influence the measurement and scaling of social value in an organization.

Lastly, Cluster 6 is related to the element of promoting SEship. For example, Korosec and Berman (2006) examined how cities help promote SEship in their communities, focusing on individuals and organizations. Herman and Rendina (2001) identified compassion as the motivation for promoting SEship and built a model of three mechanisms that transform compassion into SEship.

As shown in Table 6, Cluster 1 corresponded to the relationship between gender and the entrepreneurial pursuit of social purpose. For example, Hechavarría et al. (2017) studied how gender and national cultural values shape entrepreneurs’ goals of creating ventures that provide economic, social, or environmental value to the market. Brieger et al. (2019) analyzed the impact of human empowerment on an entrepreneur’s prosocial motivation and that of gender on prosociality in business. Hechavarría and Brieger (2020) identified the cultural practices best suited for engaging the SEship of female entrepreneurs in 33 countries.

Cluster 2 represented the social integration of women and overcoming barriers through SEship. For example, Datta and Gailey (2012) explored female entrepreneurship that empowers women by studying a women’s cooperative in the strongly patriarchal society of India. Meanwhile, Kimbu and Ngoasong (2016) explored the role of female owner-managers in small tourism firms as social entrepreneurs and how they overcome existing barriers to female participation.

Cluster 3 is related to the gender role congruence of entrepreneurs in social purpose organizations. For example, Grimes et al. (2018) developed a gender identity-based framework for explaining heterogeneity in adopting sustainability certification for social enterprises. Moreover, Yang et al. (2020) examined how gender role congruity affects social impact accelerator selection decisions.

As a result of comparing the two fields (overall SEship and women in SEship), it was noted that overall SEship research was differentiated into detailed topic clusters. In contrast, the scope of the issues covered in research on women in SEship is still limited. Specifically, compared to overall SEship, women in SEship research mainly focus on more individual-level topics, including entrepreneurial pursuit behavior, overcoming barriers, and gender role congruence. Table 7 summarizes the research focus of each cluster in the two fields. Table 7 summarizes the research focus of each cluster in the two fields.

5.2.1 Co-citation analysis—dynamic clustering analysis

To further understand the difference in the evolution of women in SEship from overall SEship, we performed a dynamic co-citation analysis. Table 8 shows the number of papers published in each cluster since 1998.

Research on women in SEship grew at the same rate in 2016 and 2017, whereas, since 2016, studies on overall SEship did not have high publications. Moreover, the number of articles falling into clusters 1 and 3 on women in SEship has steadily increased, but studies on overall SEship, divided into six commonly shared topics, were mainly distributed from 2004 to 2015. For overall SEship, many studies have been conducted in Clusters 3 and 4 and relatively few were performed in Clusters 2 and 6. Meanwhile, the first study on women in SEship appeared in 2012, and the level of interest in the subject across the three clusters was equal. In summary, the development and maturity of overall SEship research naturally shifted researchers’ attention toward specifically studying women in SEship.

5.3 Keyword network analysis

We collected author keywords to conduct a keyword network analysis. However, 144 papers that did not include author keywords were excluded from the total. Therefore, the final number of papers analyzing the keyword network of overall SEship and women in SEship was 998 and 50, respectively.

To construct a rigorous keyword network analysis, we applied the keyword network analysis process in Table 9. Thus, our study aimed to (1) generate two keyword networks (overall SEship and women in SEship) extracted from premier international business journals, (2) examine the characteristics of the two keyword network structures to identify the status of the field, (3) investigate the specific issues of overall SEship and women in SEship, and (4) examine the changes in the more influential issues over time.

Before constructing the keyword network, we refined author keywords extracted from selected papers by standardizing all keywords with the same meaning. Then, we performed a component analysis to construct networks consisting of commonly preferred keywords using the NetMiner tool.

5.3.1 Keyword network structure analysis

After constructing keyword networks consisting of commonly used author keywords, several well-defined and widely used network-related measures were applied to understand the keyword networks’ structural characteristics. First, our study adopted a “density” measure to examine the degree of dense networks by dividing the number of links by the number of possible links in the network—the more comprehensive the network, the sparser the links (Choi et al. 2011). Second, the “clustering coefficient,” which implies the degree of connectivity of the neighboring nodes (keywords) in a network, was adopted. A high clustering coefficient results in the tendency of nodes (keywords) to be grouped densely (Choi et al. 2011). Third, we applied the “average distance,” which reveals the average number of steps along the shortest arcs for all node pairs. In other words, the “average distance” implies the degree of efficiency in terms of information on a network (Choi et al. 2011).

The results of our study indicated that the overall network of SEship and the sub-network regarding women in SEship are highly clustered local networks interconnected by hub nodes (keywords) of the entire network (Table 10). The overall network of SEship is relatively sparse (density = 0.004), whereas the sub-network of women in SEship is highly dense (density = 0.033). The density results of the overall network of SEship indicated that out of 1000 potential links, only approximately four links exist in the keyword network. Although there is no established ideal density cut-off point to advise (Raisi et al. 2020), the current density of research on overall SEship is extremely low. In contrast, the sub-network of women in SEship has relatively denser connectivity.

To further identify the structural characteristics of the overall network and sub-network for SEship, our study constructed a cumulative degree distribution where the X-axis represents the degree’s log scale and the Y-axis indicates the keyword proportion. The cumulative degree of the overall network and sub-keyword networks for SEship followed a transparent power-law distribution, as shown in Fig. 3. The two networks are highly centralized around a few nodes (keywords), and the centralization has a hierarchal pattern. According to cohesion theory (Coleman 1988), higher density enables network nodes to have more opportunities to connect to other nodes, overcome impediments, and ease knowledge transfer (Reagans and McEvily 2003). Furthermore, a network’s hierarchal pattern provides easy access to many other nodes in the network, thereby improving the diffusion of knowledge. However, high centralization can impede access to diverse and new sources of knowledge as the knowledge sources are limited to a few hubs. Accordingly, although the current research on women in SEship indicates a suitable structure for a quick transfer, diffusion, and a combination of issues, it might be challenging to access diverse and new emerging issues.

5.3.2 Important keywords—network centrality analysis

Our analysis results show the top ten keywords according to three centrality measures (degree, betweenness, and closeness centrality). As shown in Table 11, the top-ranked keywords by the three centrality measures imply specific issues in each area. A keyword with a high degree centrality has many connections with other keywords, indicating their representativeness of major-specific research issues. Furthermore, because the top keywords in terms of betweenness centrality lie between two distinct research topics, it may imply that they play an essential role in bridging separate groups of research topics. A keyword with high closeness centrality is in the center of the keyword network; thus, keywords with high closeness centrality were used with nearly all other keywords.

Comparing the results of the analysis, we determined that the study of overall SEship centered on related concepts, such as “entrepreneurship,” “social innovation,” “corporate social responsibility,” and “sustainability,” by linking organizational characteristics, such as “hybrid organization” and “social business.” The study of women in SEship centered on gender identity concepts, such as “gender,” “women entrepreneur,” and “female entrepreneurship,” by linking concepts of regional activities, such as “community development.” However, in this field, the generalization is limited because of the specific data source (e.g., the global representative monitor) used in a study or the limited market area (e.g., bottom of the pyramid), which is the subject of a study, and appears as the top keyword. To sum up, overall SEship is connected by various comparisons and contrasts that use similar concepts, but the study of women in SEship is not characterized by a broad conceptual relationship.

5.3.3 Important keywords—changes in important keywords over time

To address changes in influential issues over time, we compared the important keywords from the first ten years (2010–2019) with those from the two most recent years (2020–2021) (Table 12). Furthermore, in recent years (2010–2021), we observed highly ranked new emerging keywords, identifying significant issues for overall SEship and women in SEship (Table 13). As the links between keywords have accumulated over the years, examining the keyword networks’ evolution is difficult as keyword association information from a certain period may be excluded based on the focus of the keyword network in that period. Thus, to identify the influential issues that have resulted in recent changes in impactful keywords, we compared the keyword network constructed from much earlier papers with that of more recent ones.

Our comparison reveals some notable findings. In overall SEship, “social entrepreneurship,” “social enterprise,” “social innovation,” “entrepreneurship,” “hybrid organization,” “sustainability,” and “social business” are concepts that are consistently studied, although some changes in centrality exist. Additionally, keywords that have previously received significant attention (e.g., “social entrepreneur,” “corporate social responsibility,” and “social value”) have shifted away from recent research interests, and new keywords (e.g., “legitimacy,” “gender”) have drawn attention. In the study of women in SEship, “social entrepreneurship,” “social enterprise,” “entrepreneurship,” and “female entrepreneurship” are continuously studied in conjunction with “gender” and “women.” However, existing keywords (e.g., “global entrepreneurship monitor,” “community”) have disappeared, and other keywords (e.g., “bottom of the pyramid,” “social innovation,” “culture”) replaced them. The study-analyzing GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), consisting of representative entrepreneurship survey data, was useful in identifying gender differences in activities that pursue social values in overall entrepreneurship (Brieger et al. 2019; Hechavaría et al. 2017). These empirical results served as the basis for exploring gender differences in the specific contexts of emerging markets (Rosca et al. 2020) and innovation areas (Sun and Im 2015).

Table 13 represents the important issues or concepts concerning recent changes in impactful keywords. In the study of overall SEship, cooperative management methods (“cross-sector collaboration,” “co-creation,” “collaboration,” “crowdsourcing,” and “value co-creation”) and measurement of created value (“measurement,” “social impact measurement,” and “financial performance”) have been continuously researched from the beginning.

Meanwhile, in the study of women in SEship, the types of keywords that stand out are the characteristics of the area (“community development,” “developing country,” “community enterprise,” “community,” “least developed country,” and “bottom of the pyramid”), gender characteristics (“gender self-schema,” “social identity theory,” and “gender role congruity theory”), and ways to overcome resource constraints (“social bricolage,” “philanthropy,” “crowdfunding,” “sustainable finance,” “microfinance,” and “charity”). The definition and explanation of the concept of SEship gradually became a concrete subject of practical management methods and performance measurement. However, the study of women in SEship focuses only on overcoming resource-constrained environments (regional, cultural). In other words, this indicates that gender-based research on SEship has not yet fully addressed the complexity of entrepreneurship research.

6 Research gaps and future research opportunities

Our rigorous systematic literature review has identified gaps in current research and potential future research opportunities in the field of women in SEship, which may be beneficial for scholars to capture emerging research topics in their studies. This study has several notable findings.

6.1 Reinterpretation of theoretical concepts in SEship

Recent research on women in SEship has focused on women’s role in addressing gender discrimination within the field of SEship rather than the theoretical definition and concept of SEship. This can be seen from the fact that women in SEship had minimal keywords associated with the theoretical definition and concept of SEship, based on the cluster analysis results (Table 7) and the top keyword by centrality (Table 11). In recent decades, researchers have identified unique phenomena and behavioral meanings in the field of SEship. However, most research on women in SEship is based on existing entrepreneurship and women’s research rather than on discussions of SEship. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct theoretical research on SEship from a woman’s perspective. We suggest more studies with a focus on reinterpreting the existing theoretical concepts in SEship, such as “social innovation,” “hybrid organization,” and “sustainability” from the perspective of women.

6.2 Social integration and overcoming gender discrimination

The main current themes, which underline the importance of women in the fight against discrimination and promote social integration, are expected to continue to grow (Table 8). According to the characteristics of the network structure, the structural characteristics of the knowledge network regarding women in SEship have high centrality and clustering coefficients (Table 10), which enables the transfer and diffusion of extant knowledge (topics) within the given field. In addition, the knowledge network of women in SEship has shown preferential attachment as a well-known feature of the power-law distribution (Fig. 3). Thus, the more the existing issues with high centrality regarding “gender,” “women entrepreneur,” and “female entrepreneurship” represent a focus on the importance of women in SEship, the more often the issues will be selected by researchers (Barabási 2009). Therefore, we suggest ways for female social entrepreneurs to overcome gender discrimination and create sustainable value may be a potential area for fruitful research in future of women in SEship.

6.3 Expansion of sectors and regions

In the existing study, some issues such as “hybrid organization” and “corporate social responsibility” remain unclear in the study of women in SEship. According to the keyword network analysis (Tables 11, 12), “hybrid organization” is an issue that is strongly linked to other research themes but has rarely been addressed from a woman’s perspective. Moreover, “corporate social responsibility” is a field that is often studied in overall SEship research, but the study of women in SEship has rarely focused on this topic. These findings raise the need to comprehensively study various sectors in which female social entrepreneurs operate. Therefore, there is a need for research into sectors other than the social economy (e.g., for-profit, nonprofit, and public sector). Furthermore, the area and geographical scope of female entrepreneurs’ activities are somewhat limited (e.g., “community development,” “developing country”, and “bottom of the pyramid”). Hence, further expanding the geographical ranges and contexts of women in SEship field is necessary for future research (Kerlin 2010; Hechavaría and Brieger 2020).

6.4 Operation strategy and performance factors

It is necessary to pay attention to “collaboration” and “performance measurement” in the field of women in SEship. Based on the new emerging keyword network result in the study of overall SEship, it is noteworthy that the topics related to “collaboration” (such as “cross-sector collaboration,” “co-creation,” “collaboration,” “crowdsourcing,” and “value co-creation”), “performance measurement” (such as “measurement,” “social impact measurement,” and “financial performance”) have recently emerged. Women cooperate at various levels as entrepreneurs, organizational members, and residents in the field of overall SEship (Maas et al. 2014; Anglin et al. 2021; Bento et al. 2019). Therefore, this study recommends more studies focusing on identifying traits of women’s collaboration and creating values through women’s cooperation.

7 Conclusion

The study of SEship and the research on women in SEship has increased in popularity in recent years. Hence, synthesizing and reflecting on the existing literature regarding women in SEship field are essential in identifying new directions and future challenges. Therefore, we conducted a systematic literature review to gain a more comprehensive evaluation of research on women in SEship by combining a bibliometric analysis and network analysis (citation analysis, co-citation analysis) with a keyword network analysis.

7.1 Implications of this study

The implications of this study are as follows. First, an overview of women in SEship is presented to help researchers identify research opportunities and develop new perspectives. Existing systematic review papers have examined overall SEship (Hota et al. 2020; Sassmannshausen and Volkmann 2018), but most did not compare and address topics on women. Thus, our goal was to identify the current status and capture research gaps on women in SEship within the overall study of SEship. Our notable findings provide meaningful guidelines for experienced and new scholars in the field of women in SEship. For example, our results provide detailed answers to practical questions about which journals are being studied, which keywords are important, which researchers are conducting unique research, and the latest trends.

Second, we conducted a rigorous systematic literature review to comprehensively evaluate research on women in SEship by combining the traditional systematic literature review approach (citation and co-citation analysis) with a keyword network analysis. The keyword network analysis can complement the perceived drawbacks of the extant systematic literature review with a more specific knowledge network (Choi et al. 2011; Park and Jeong 2019).

Third, our notable findings provide meaningful guidelines for experienced and new scholars in the field of women in SEship. For example, our results provide detailed answers to practical questions about which journals are being studied, which keywords are important, which researchers are conducting unique research, and the latest trends.

7.2 Limitations and future research

Although this study is valuable because it overcomes limitations due to the lack of literature reviews, it is not without limits. First, a limitation exists in the selection of research papers. Although SCOPUS, used in this study, is a database favored by many researchers, some related papers may have been excluded from manual search methods. This is because confirming information is difficult because of errors, such as limitations in searching for related journals and the omission of contents. Similarly, even though we selected search keywords related to the research topic, these keywords may not be exhaustive. Thus, we suggest that future systematic literature reviews include other diverse databases (e.g., Web of Science). Moreover, for more rigorous analysis, the future systematic literature reviews must use not only the author’s keywords but also titles and abstracts.

Second, the academic field of the collected papers is limited to business administration. Although research on SEship is conducted in a multidisciplinary manner, this study examined research trends only in the field of business administration, so discussions in other academic areas were excluded. Therefore, future research must explore the differences and associations in discussions by the academic field.

Third, there are limitations to the method of analysis. For example, the citation index used in the study is a representative indicator of the influence of the study, but it has limitations as it can be cited for other reasons, such as the reputation of the author or journal (Hota et al. 2020). Moreover, common topics were extracted and classified based on the literature derived from cluster analysis, but the core topics of all studies are difficult to explain. This is because topics were clustered based on the relationship between the main and sub-themes of each study. Therefore, the limitations of such a citation index and cluster analysis must be recognized, and more intensified content analysis should be conducted based on this study.

Lastly, this study examined only academic literature and excluded conference papers, book series, commercial publications, and magazine articles. Therefore, the results of this study reflect only the academic discussions of researchers. To reflect future discussions of practice, researchers must include a broader range of data. The similarities and differences between practitioners’ and scholars’ interests can be compared through this.

References

Anggadwita G, Ramadani V, Permatasari A, Alamanda DT (2021) Key determinants of women’s entrepreneurial intentions in encouraging social empowerment. Serv Bus 15(2):309–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-021-00444-x

Anglin AH, Courtney C, Allison TH (2021) Venturing for others, subject to role expectations? A role congruity theory approach to social venture crowd funding. Entrep Theory Pract 46(2):421–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211024545

Austin J, Stevenson H, Wei-Skillern J (2006) Social and commercial entrepreneurship: same, different, or both? Entrep Theory Pract 30(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00107.x

Ayogu DU, Agu EO (2015) Assessment of the contribution of women entrepreneur towards entrepreneurship development in Nigeria. Int J Curr Res Acad Rev 3(10):190–207

Bacq S, Janssen F (2011) The multiple faces of social entrepreneurship: A review of definitional issues based on geographical and thematic criteria. Entrep Reg Dev 23(5-6):373–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.577242

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Galindo MÁ, Méndez MT (2012) Women’s entrepreneurship and economic policies. In: Galindo M-A, Ribeiro D (eds) Women’s entrepreneurship and economics. Springer, New York, pp 23–33

Barabási AL (2009) Scale-free networks: a decade and beyond. Science 325(5939):412–413. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1173299

Battilana J, Lee M (2014) Advancing research on hybrid organizing–Insights from the study of social enterprises. Acad Manag Ann 8(1):397–441. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.893615

Bento N, Gianfrate G, Thoni MH (2019) Crowdfunding for sustainability ventures. J Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117751

Blondel VD, Guillaume JL, Lambiotte R (2008) Lefebvre E (2008) Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J Stat Mech Theory Exp 10:P10008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008

Brandsen T, Karré PM (2011) Hybrid organizations: no cause for concern? Int J Public Adm 34(13):827–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2011.605090

Brieger SA, Terjesen SA, Hechavarría DM, Welzel C (2019) Prosociality in business: a human empowerment framework. J Bus Ethics 159(2):361–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4045-5

Brin S, Page L (1998) The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine. Comput Netw ISDN Syst 30:107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7552(98)00110-X

Calás MB, Smircich L, Bourne KA (2009) Extending the boundaries: reframing “entrepreneurship as social change” through feminist perspectives. Acad Manag Rev 34(3):552–569. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.40633597

Cardella GM, Hernández-Sánchez BR, Monteiro AA, Sánchez-García JC (2021) Social entrepreneurship research: intellectual structures and future perspectives. Sustain 13(14):7532. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147532

Castellas EI, Stubbs W, Ambrosini V (2019) Responding to value pluralism in hybrid organizations. J Bus Ethics 159(3):635–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3809-2

Chell E (2007) Social enterprise and entrepreneurship: towards a convergent theory of the entrepreneurial process. Int Small Bus J 25(1):5–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242607071779

Choi J, Yi S, Lee KC (2011) Analysis of keyword networks in MIS research and implications for predicting knowledge evolution. Inf Manag 48(8):371–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2011.09.004

Clauset A, Newman ME, Moore C (2004) Finding community structure in very large networks. Phys Rev E. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2010.488396

Coleman JS (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94:S95–S120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

Culnan MJ, Markus ML (1987) Information technologies. In: Jablin FM, Putnam LL, Roberts KH, Porter LW (eds) Handbook of organizational communication: an interdisciplinary perspective. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park, pp 420–443

Dacin PA, Dacin MT, Matear M (2010) Social entrepreneurship: why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Acad Manag Perspect 24(3):37–57. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.24.3.37

Dacin MT, Dacin PA, Tracey P (2011) Social entrepreneurship: a critique and future directions. Organ Sci 22(5):1203–1213. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0620

Dart R (2004) The legitimacy of social enterprise. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 14(4):411–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.43

Datta PB, Gailey R (2012) Empowering women through social entrepreneurship: case study of a women’s cooperative in India. Entrep Theory Pract 36(3):569–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00505.x

Dees JG (1998) The meaning of “social entrepreneurship.” Comments and suggestions contributed from the Social Entrepreneurship Founders Working Group. Durham, NC: Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship, Fuqua School of Business, Duke University.

Di Lorenzo F, Scarlata M (2019) Social enterprises, venture philanthropy and the alleviation of income inequality. J Bus Ethics 159(2):307–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4049-1

Dickel P, Eckardt G (2021) Who wants to be a social entrepreneur? The role of gender and sustainability orientation. J Small Bus Manag 59(1):196–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2019.1704489

Dimitriadis S, Lee M, Ramarajan L, Battilana J (2017) Blurring the boundaries: the interplay of gender and local communities in the commercialization of social ventures. Organ Sci 28(5):819–839. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1144

Fahimnia B, Tang CS, Davarzani H, Sarkis J (2015) Quantitative models for managing supply chain risks: a review. Eur J Operat Res 247(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.04.034

George C, Reed MG (2016) Building institutional capacity for environmental governance through social entrepreneurship: lessons from Canadian biosphere reserves. Ecol Soc 21(1):18. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08229-210118

Gillett A, Loader K, Doherty B, Scott JM (2019) An examination of tensions in a hybrid collaboration: a longitudinal study of an empty homes project. J Bus Ethics 157(4):949–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3962-7

Grimes MG, Gehman J, Cao K (2018) Positively deviant: Identity work through B Corporation certification. J Bus Ventur 33(2):130–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.12.001

Gupta VK, Wieland AM, Turban DB (2019) Gender characterizations in entrepreneurship: a multi-level investigation of sex-role stereotypes about high-growth, commercial, and social entrepreneurs. J Small Bus Manag 57(1):131–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12495

Gupta P, Chauhan S, Paul J, Jaiswal MP (2020) Social entrepreneurship research: a review and future research agenda. J Bus Res 113:209–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.032

Hashemi H, Rajabi R, Brashear-Alejandro TG (2022) COVID-19 research in management: an updated bibliometric analysis. J Bus Res 149:795–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.05.082

Haugh HM, Talwar A (2016) Linking social entrepreneurship and social change: the mediating role of empowerment. J Bus Ethics 133(4):643–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2449-4

Hechavarría DM, Brieger SA (2020) Practice rather than preach: cultural practices and female social entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 58:1131–1151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00437-6

Hechavarría DM, Terjesen SA, Ingram AE, Renko M, Justo R, Elam A (2017) Taking care of business: the impact of culture and gender on entrepreneurs’ blended value creation goals. Small Bus Econ 48(1):225–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9747-4

Hechavarría D, Bullough A, Brush C, Edelman L (2019) High-growth women’s entrepreneurship: fueling social and economic development. J Small Bus Manag 57(1):5–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12503

Hjørland B (2013) Citation analysis: A social and dynamic approach to knowledge organization. Inf Process Manag 49(6):1313–1325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2013.07.001

Hota PK, Subramanian B, Narayanamurthy G (2020) Mapping the intellectual structure of social entrepreneurship research: a citation/co-citation analysis. J Bus Ethics 166(1):89–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04129-4

Huisman M, Van Duijn MAJ (2005) Software for social network analysis. In: Carrington PJ, Scott J, Wasserman S (eds) Models and methods in social network analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 270–316

Kannampuzha M, Hockerts K (2019) Organizational social entrepreneurship: scale development and validation. Soc Enterp J 15(3):290–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-06-2018-0047

Kelley DJ, Baumer BS, Brush C, Greene PG, Mahdavi M, Majbouri M, et al (2017) Women’s entrepreneurship 2016/2017 report. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. 9(19)

Kerlin JA (2006) Social enterprise in the United States and Europe: understanding and learning from the differences. Voluntas 17(3):247–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-006-9016-2

Kerlin JA (2010) A comparative analysis of the global emergence of social enterprise. Voluntas 21(2):162–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-010-9126-8

Kim JR (2022) People-centered entrepreneurship: the impact of empathy and social entrepreneurial self-efficacy for social entrepreneurial intention. Glob Bus Financ Rev 27(1):108–118. https://doi.org/10.17549/gbfr.2022.27.1.108

Kimbu AN, Ngoasong MZ (2016) Women as vectors of social entrepreneurship. Ann Tour Res 60:63–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.002

Kistruck GM, Beamish PW (2010) The interplay of form, structure, and embeddedness in social intrapreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 34(4):735–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00371.x

Korosec RL, Berman EM (2006) Municipal support for social entrepreneurship. Public Adm Rev 66(3):448–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00601.x

Langowitz N, Minniti M (2007) The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrep Theory Pract 31(3):341–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00177.x

Lee M, Huang L (2018) Gender bias, social impact framing, and evaluation of entrepreneurial ventures. Organ Sci 29(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1172

Lee SH, Jung KS (2015) The role of social support for reemployed women. Glob Bus Financ Rev 20(2):49–57. https://doi.org/10.17549/gbfr.2015.20.2.49

Leydesdorff L (2011) Bibliometrics/citation networks. In: Barnett GA (ed) Encyclopedia of social networks. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 72–74

Lindsay G, Hems L (2004) Societes cooperatives d’interet collectif: the arrival of social enterprise within the French social economy. Voluntas 15(3):265–286. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:VOLU.0000046281.99367.29

Lortie J, Castrogiovanni GJ, Cox KC (2017) Gender, social salience, and social performance: how women pursue and perform in social ventures. Entrep Reg Dev 29(1–2):155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1255433

Maas J, Seferiadis AA, Bunders JF, Zweekhorst MB (2014) Bridging the disconnect: how network creation facilitates female Bangladeshi entrepreneurship. Int Entrepreneurship Manag J 10(3):457–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0299-2

Mair J, Marti I (2006) Social entrepreneurship research: a source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J World Bus 41(1):36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.09.002

Mair J, Marti I (2009) Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: a case study from Bangladesh. J Bus Ventur 24(5):419–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.04.006

McQuilten G (2017) The political possibilities of art and fashion based social enterprise. Continuum 31(1):69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2016.1262103

Meyskens M, Robb–Post C, Stamp JA, Carsrud AL, Reynolds PD (2010) Social ventures from a resource–based perspective: An exploratory study assessing global Ashoka fellows. Entrep Theory Pract 34(4):661–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00389.x

Nega B, Schneider G (2014) Social entrepreneurship, microfinance, and economic development in Africa. J Econ Issues 48(2):367–376. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEI0021-3624480210

Nguyen L, Szkudlarek B, Seymour RG (2015) Social impact measurement in social enterprises: an interdependence perspective. Can J Adm Sci 32(4):224–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1359

Nicholls A (2010) The legitimacy of social entrepreneurship: Reflexive isomorphism in a pre–paradigmatic field. Entrep Theory Pract 34(4):611–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00397.x

Noguera M, Alvarez C, Urbano D (2013) Socio-cultural factors and female entrepreneurship. Int Entrep Manag J 9(2):183–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0251-x

Pache AC, Santos F (2013) Inside the hybrid organization: Selective coupling as a response to competing institutional logics. Acad Manage J 56(4):972–1001. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0405

Park JS, Jeong EB (2019) Service quality in tourism: a systematic literature review and keyword network analysis. Sustainability 11(13):3665. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133665

Peredo AM, McLean M (2006) Social entrepreneurship: a critical review of the concept. J World Bus 41(1):56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007

Phillips W, Lee H, Ghobadian A, O’Regan N, James P (2015) Social innovation and social entrepreneurship. Group Organ Manag 40(3):428–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114560063

Prabhu GN (1999) Social entrepreneurship leadership. Career Dev Int 4(3):140–145. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620439910262796

Radicchi F, Castellano C, Cecconi F, Loreto V, Parisi D (2004) Defining and identifying communities in networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am 101:2658–2663. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0400054101

Rae D (2015) Book review: Handbook on the entrepreneurial university. Sage publication.

Raisi H, Baggio R, Barratt-Pugh L, Willson G (2020) A network perspective of knowledge transfer in tourism. Ann Tour Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102817

Reagans R, McEvily B (2003) Network structure and knowledge transfer: the effects of cohesion and range. Adm Sci Q 48(2):240–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/3556658

Rey-Martí A, Ribeiro-Soriano D, Palacios-Marqués D (2016) A bibliometric analysis of social entrepreneurship. J Bus Res 69(5):1651–1655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.033

Rosca E, Agarwal N, Brem A (2020) Women entrepreneurs as agents of change: a comparative analysis of social entrepreneurship processes in emerging markets. Technol Forecast Soc Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120067

Roy K, Karna A (2015) Doing social good on a sustainable basis: competitive advantage of social businesses. Manag Decis 53(6):1355–1374. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-09-2014-0561

Saebi T, Foss NJ, Linder S (2019) Social entrepreneurship research: Past achievements and future promises. J Manag 45(1):70–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318793196

Sahrakorpi T, Bandi V (2021) Empowerment or employment? Uncovering the paradoxes of social entrepreneurship for women via Husk Power Systems in rural North India. Energy Res Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102153

Santos FM (2012) A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. J Bus Ethics 111(3):335–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1413-4

Sassmannshausen SP, Volkmann C (2018) The scientometrics of social entrepreneurship and its establishment as an academic field. J Small Bus Manag 56(2):251–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12254

Savarese C, Huybrechts B, Hudon M (2021) The influence of interorganizational collaboration on logic conciliation and tensions within hybrid organizations: insights from social enterprise–corporate collaborations. J Bus Ethics 173(4):709–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04557-7

Seelos C, Mair J (2005) Social entrepreneurship: creating new business models to serve the poor. Bus Horiz 48(3):241–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2004.11.006

Short JC, Moss TW, Lumpkin GT (2009) Research in social entrepreneurship: past contributions and future opportunities. Strateg Entrep J 3(2):161–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.69

Simón-Moya V, Revuelto-Taboada L, Ribeiro-Soriano D (2012) Are success and survival factors the same for social and business ventures? Serv Bus 6(2):219–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-012-0133-2

Sulphey MM, Alkahtani N (2017) Economic security and sustainability through social entrepreneurship: the current Saudi scenario. J Secur Sustain 6(3):479–490

Sun SL, Im JY (2015) Cutting microfinance interest rates: an opportunity co-creation perspective. Entrep Theory Pract 39(1):101–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12119

Tan LP, Le ANH, Xuan LP (2020) A systematic literature review on social entrepreneurial intention. J Social Entrep 11(3):241–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2019.1640770

Thomas A (2004) The rise of social cooperatives in Italy. Voluntas 15(3):243–263. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:VOLU.0000046280.06580.d8

Thompson J, Alvy G, Lees A (2000) Social entrepreneurship–a new look at the people and the potential. Manag Decis 38(5):328–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740010340517

Tracey P, Jarvis O (2007) Toward a theory of social venture franchising. Entrep Theory Pract 31(5):667–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00194.x

Tripathy KK, Paliwal M, Singh A (2022) Women’s social entrepreneurship and livelihood innovation: an exploratory study from India. Serv Bus. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-022-00493-w

Van Ryzin G, Grossman S, Di Padova-Stocks L, Bergrud E (2009) Portrait of the social entrepreneur: statistical evidence from a US panel. Volunt Int J Volunt Nonprofit Organ 20(2):129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-009-9081-4

Xu X, Chen X, Jia F, Brown S, Gong Y, Xu Y (2018) Supply chain finance: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Int J Prod Econ 204:160–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.08.003

Yang S, Kher R, Newbert SL (2020) What signals matter for social startups? It depends: the influence of gender role congruity on social impact accelerator selection decisions. J Bus Ventur. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.03.001

Zahra SA, Newey LR, Li Y (2014) On the frontiers: the implications of social entrepreneurship for international entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 38(1):137–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12061

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeong, E., Yoo, H. A systematic literature review of women in social entrepreneurship. Serv Bus 16, 935–970 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-022-00512-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-022-00512-w